Abstract

Background

Choledochal malformations comprise various congenital cystic dilatations of the extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic biliary tree. Choledochal malformation is generally considered a premalignant condition, but reliable data on the risk of malignancy and optimal surgical treatment are lacking. The objective of this systematic review was to assess the prevalence of malignancy in patients with choledochal malformation and to differentiate between subtypes. In addition, the risk of malignancy following cystic drainage versus complete cyst excision was assessed.

Methods

A systematic review of PubMed and Embase databases was performed in accordance with the PRISMA statement. A meta‐analysis of the risk of malignancy following cystic drainage versus complete cyst excision was undertaken in line with MOOSE guidelines. Prevalence of malignancy was defined as the rate of biliary cancer before resection, and malignant transformation as new‐onset biliary cancer after surgery.

Results

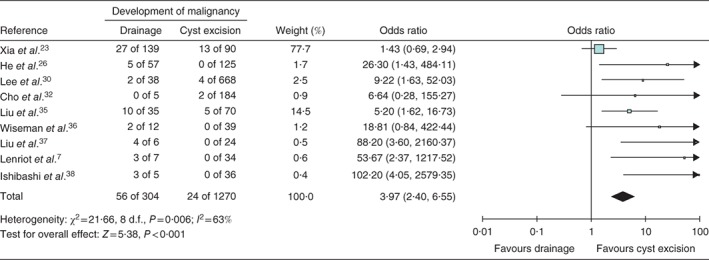

Eighteen observational studies were included, reporting a total of 2904 patients with a median age of 36 years. Of these, 312 in total developed a malignancy (10·7 per cent); the prevalence of malignancy was 7·3 per cent and the rate of malignant transformation was 3·4 per cent. Patients with types I and IV choledochal malformation had an increased risk of malignancy (P = 0·016). Patients who underwent cystic drainage had an increased risk of developing biliary malignancy compared with those who had complete cyst excision, with an odds ratio of 3·97 (95 per cent c.i. 2·40 to 6·55).

Conclusion

The risk of developing malignancy among patients with choledochal malformation was almost 11 per cent. The malignancy risk following cystic drainage surgery was four times higher than that after complete cyst excision. Complete surgical resection is recommended in patients with choledochal malformation.

Short abstract

Choledochal cysts should be resected

Introduction

Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilatations of the extrahepatic and/or intrahepatic biliary tree. Owing to variation in involvement of the biliary tree among subtypes of choledochal cysts and new insights into epithelial markers, the more recent term for this condition is choledochal malformation1, 2. Choledochal malformations occur three to four times more often in women. Choledochal malformations are fairly common in the Asian population3 and rarer in Western countries. Choledochal malformation is considered a premalignant condition, but to date its carcinogenic mechanisms have not been elucidated4. This risk of cancer provides the basis for the current treatment concept: surgical resection of the entire affected biliary tract with subsequent construction of a biliodigestive anastomosis. The bilioenteric anastomosis can be a hepaticojejunostomy or hepaticoduodenostomy. Hepaticoduodenostomy is associated with more complications, such as cholangitis and bile reflux, and also with development of malignancy5. Therefore, complete cyst excision followed by a Roux‐en‐Y hepaticojejunostomy is the standard procedure nowadays. In asymptomatic patients, this treatment might be considered as prophylactic surgery. Previously, drainage procedures such as cystoduodenostomy were also performed, but such procedures seem to have a much higher risk of malignancy because abnormal biliary epithelium remains in situ 6, 7.

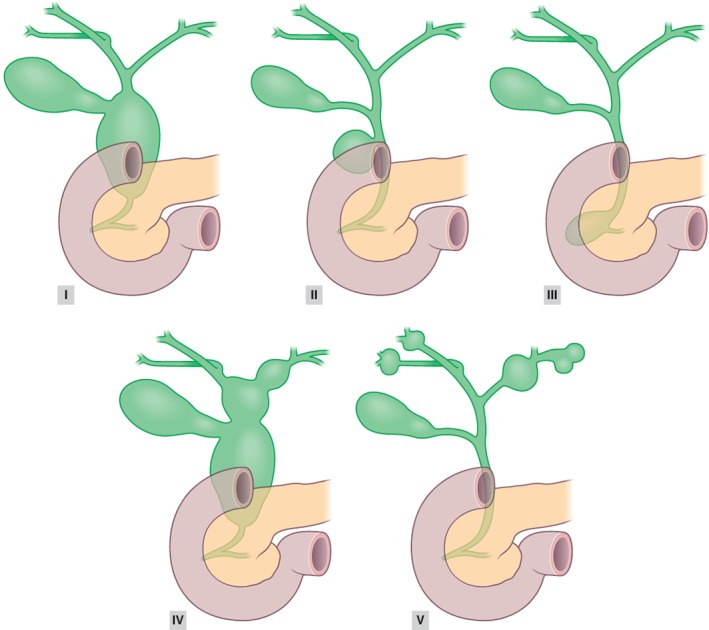

Malignancies develop in 2·5–26 per cent of patients with choledochal malformation4. Choledochal malformations are classified according to Todani and colleagues (Fig. 1)5. Several authors8, 9, 10, 11 consider the development of malignancy in choledochal malformations to be related to the aetiology of the different types of malformation. It could be speculated that prolonged reflux of pancreatic secretions into the biliary tract occurs in Todani types I and IV, which frequently present with abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junctions12. Prolonged reflux might lead to malignant degeneration of the biliary epithelium8, 13. The situation is supposedly different in types II and III choledochal malformations, which might be true congenital malformations in which reflux is absent14.

Figure 1.

Todani classification of choledochal malformations5

Precise estimates of the risk of carcinogenesis in choledochal malformation are lacking. The aim of this systematic review was to assess the prevalence of malignancy in both paediatric and adult patients with choledochal malformation, and to determine the possible differences between Todani types I and IV versus types II and III. The secondary aim was to investigate the risk of malignant transformation in patients with choledochal malformation who either did or did not undergo surgery, and to investigate the prevalence of malignancy by decade of age.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement15. Two reviewers independently selected studies, extracted data and appraised the studies critically. Any differences of opinion between reviewers were resolved by discussion. If they failed to reach agreement, a third reviewer was consulted to achieve consensus. This review was registered in PROSPERO, the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews (CRD42016048392)16.

Literature search strategy

A systematic search of the PubMed and Embase databases was performed for articles relevant to the prevalence of malignancies and/or malignant transformations in patients with choledochal malformation, published between 1 January 1995 and 1 June 2016. The electronic searches were supplemented by manual reference checks of papers in recent reviews. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms ‘choledochal malformation’, ‘bile duct cyst’, ‘malignant’ and ‘carcinoma’ were used for both databases. For searching in Embase, the keyword ‘common bile duct cyst’ was added.

Definitions

Prevalence of malignancy was defined as the presence of a gallbladder carcinoma and/or cholangiocarcinoma at the time of diagnosis or an incidental finding during surgery without previous intervention. Prevalence of malignancy is the primary risk of malignancy in choledochal malformation and can be considered as risk of malignancy according to the natural history of disease. Malignant transformation was defined as the development of a cholangiocarcinoma following a surgical drainage procedure or formal excision of the choledochal malformation.

Literature screening

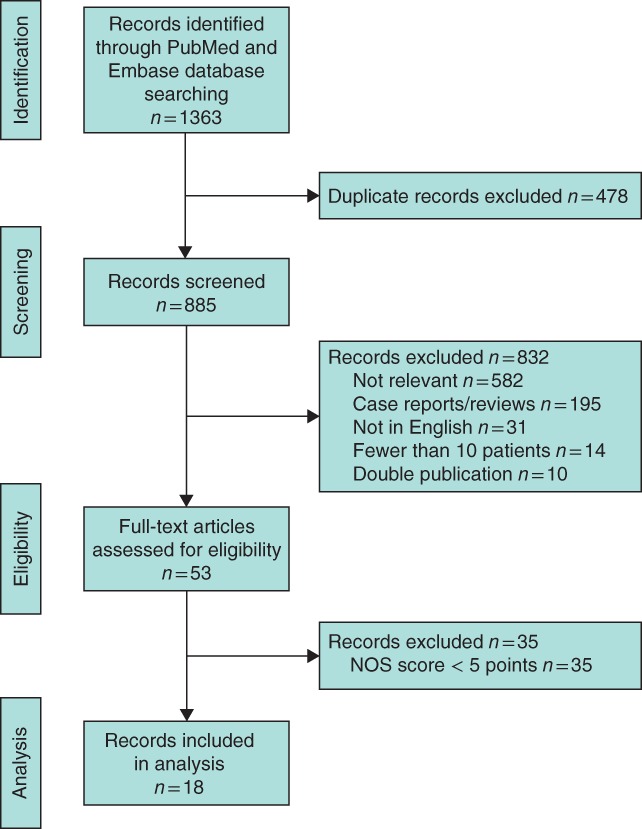

According to the PRISMA guidelines, the studies were selected in three phases (Fig. 2). During the identification phase, duplicates from different databases were removed. During the screening phase, abstracts of all studies accepted during the identification phase were reviewed. Reasons for exclusion were language other than English, reviews, case reports, studies with fewer than ten patients, and studies with a subject that was not relevant. During the eligibility phase, the methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies17.

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing selection of articles for review. NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

Data extraction and critical appraisal

Predesigned forms were used in triplicate to record the data. Data included: study design, patient population, choledochal malformation type, follow‐up time, type of surgery, and prevalence of malignancy and/or transformation. Multiple publications describing the same or overlapping series of patients were identified, and the data included only once to avoid double counting. The level of evidence for each article was assessed using the Levels of Evidence scale developed by the Oxford Centre for Evidence‐based Medicine18. Quality of the articles was assessed according to the NOS for cohort studies. This scale scores selection, comparability and outcome, with a maximum score of 9 points. Only studies that scored at least 5 points were included in the review. Overall quality of the evidence was judged by means of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach19.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables, reported as numbers with percentages, were analysed using the χ2 test. Overall effects were determined using the Z score. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0·050 (2‐sided). The χ2 statistic and the inconsistency quantity I 2 were used to determine heterogeneity. An I 2 value of 50 per cent or more represented substantial heterogeneity20. A meta‐analysis, with development of malignancy as outcome measure, was performed using RevMan software (Review Manager version 5.0.21; Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) and the results were displayed in a forest plot. The meta‐analysis was carried out in accordance with MOOSE guidelines21. Only studies that provided information on the parameters analysed were included. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Of 1363 records identified during the initial search, 18 fell within the scope of this study7, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 (Fig. 2). All records represented retrospective observational studies. The studies scored at least 5 of 9 on the NOS scale, and provided evidence at level 4 on the Oxford Levels of Evidence scale (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Reference | Country, study interval | NOS score | n | Follow‐up (years)* | Total with malignancy | Died | Age at detection of malignancy (years)† | Prevalence of malignancy | Malignant transformation | Interval between surgery and malignancy (years)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moslim et al. 22 | USA 1984–2014 | 5 | 67 | 2·1 (0·4–4·2)† | 5 (7) | 3 (60) | 55 (47–74) | 5 (7) | – | – |

| Xia et al. 23 | China 1994–2013 | 7 | 268 | 8·3 (1·5–18·8)† | 55 (20·5) | n.a. | 54·3 (32–75) | 15 (5·6) | 40 (14·9) | n.a. |

| Soares et al. 24 | USA 1972–2014 | 6 | 394 | 2·3 | 25 (6·3) | n.a. | 57 | 12 (3·0) | 13 (3·3) | n.a. |

| Machado et al. 25 | Oman 1998–2013 | 5 | 10 | 6·0 (0·3–12)† | 0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – |

| He et al. 26 | China 1968–2013 | 6 | 214 | 9·3 | 15 (7·0) | 12 (80) | 49 (28–75) | 10 (4·7) | 5 (2·3) | 15 (6–37) |

| Katabi et al. 27 | USA 1990–2008 | 5 | 36 | n.a. | 5 (14) | 4 (80) | 52 (35–65) | 5 (14) | 0 (0) | – |

| Mabrut et al. 28 | France 1978–2011 | 6 | 155 | 2·9 (0·3–25)† | 8 (5·2) | 4 (50) | 66·5 (54–74) | 8 (5·2) | 0 (0) | – |

| Ohashi et al. 29 | Japan 1971–2006 | 6 | 94 | 15·1 (0·6–40·3)† | 4 (4) | 3 (75) | 44 (27–65) | 0 (0) | 4 (4) | 19 (13–32) |

| Lee et al. 30 | South Korea 1990–2007 | 6 | 808 | 4·3 | 80 (9·9) | n.a. | 50 (21–82) | 74 (9·2) | 6 (0·7) | 4 (1–20) |

| Takeshita et al. 31 | Japan 1968–2008 | 5 | 180 | 8·3 (0·1–28·8) | 37 (20·6) | n.a. | n.a. | 36 (20·0) | 1 (0·6) | 1 |

| Cho et al. 32 | South Korea 1995–2009 | 5 | 204 | 5·6 (0·8–15)† | 22 (10·8) | 10 (45) | 48 | 20 (9·0) | 2 (1·0) | 0·8 (0·5–1·1) |

| Huang et al. 33 | Taiwan 1981–2006 | 5 | 94 | 8·9 (2–26) | 11 (12) | 7 (64) | 57 (32–82) | 11 (12) | 0 (0) | – |

| Ono et al. 34 | Japan 1981–2008 | 6 | 56 | 17 (10–27) | 2 (4) | 2 (100) | 19 (12–26) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 26 |

| Liu et al. 35 | China 1981–2006 | 6 | 153 | 10 (1–18) | 16 (10·5) | n.a. | n.a. | 0 (0) | 16 (10·5) | n.a. |

| Wiseman et al. 36 | Canada 1985–2002 | 6 | 51 | 5·1 (2–18) | 4 (8) | n.a. | n.a. | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | n.a. |

| Liu et al. 37 | China 1989–2000 | 6 | 30 | 5·5† | 9 (30) | n.a. | 43 (29–64) | 5 (17) | 4 (13) | n.a. |

| Lenriot et al. 7 | France 1980–1992 | 6 | 42 | 6·9 (0·4–16) | 5 (12) | 5 (100) | 40 (29–51) | 2 (5) | 3 (7) | 16 (18–27) |

| Ishibashi et al. 38 | Japan 1975–1996 | 6 | 48 | n.a. | 9 (19) | 6 (67) | 49 (28–66) | 6 (13) | 3 (6) | 10 (1·3–27) |

| Overall | 2904 | 312 (10·7) | 212 (7·3) | 100 (3·4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise; values are

mean (range) and

median (range).

The quality of evidence in all studies was level 4 on the Oxford Levels of Evidence scale. n.a., Not available.

Ethnicity, sex and type of choledochal malformation

Characteristics of the 18 studies are summarized in Table 1. Six23, 29, 30, 31, 32, 37 studies described Asian populations, one7 described a European population, one25 a Middle Eastern population, one22 a population with Caucasian patients, and four studies24, 27, 28, 36 described populations with both Asian and Caucasian patients. The remaining five studies26, 33, 34, 35, 38 did not specifically describe the study population, but were authored by Asian institutions. The 18 studies reported on a total of 2904 patients, 1655 (57·0 per cent) of whom were of Asian descent and 669 (23·0 per cent) of non‐Asian descent; descent was unknown for 580 patients (20·0 per cent). The sex of 2636 patients was known; of these, 1925 (73·0 per cent) were women.

The type of choledochal malformation was available for 2304 patients. The majority of patients (2049, 88·9 per cent) had types I or IV malformations, 59 (2·6 per cent) had types II or III and 196 (8·5 per cent) had Type V. Two studies did not provide follow‐up data27, 38. The median age at time of diagnosis was 36 (range 0·1–82) years.

Malignancy rate

Overall, 312 of the 2904 patients (10·7 per cent) developed a malignancy. This was subdivided into tumours present during primary surgery, which was the case in 212 patients (7·3 per cent), and tumours that developed during follow‐up, which affected 100 patients (3·4 per cent). Of these 100 patients, 42 (42·0 per cent) were treated with some kind of drainage procedure, 36 (36·0 per cent) underwent complete cyst excision followed by a Roux‐en‐Y hepaticojejunostomy, and in 22 patients (22·0 per cent) the treatment was unknown. Information about survival of patients with malignancy was provided by ten studies7, 22, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, 33, 34, 38. Included studies reported mortality rates of between 45 and 100 per cent (Table 1).

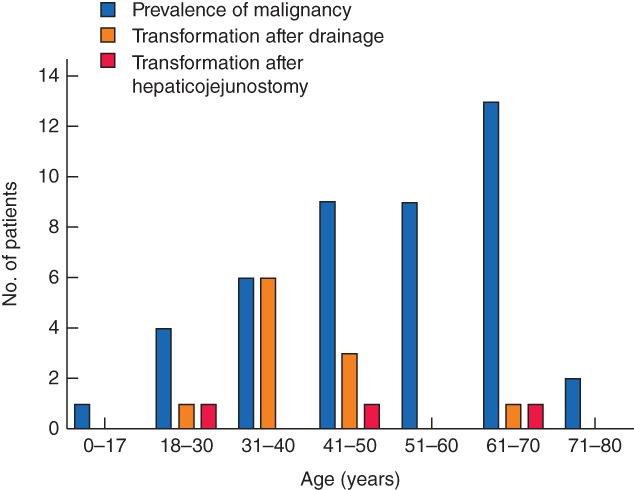

Age at development of malignancy

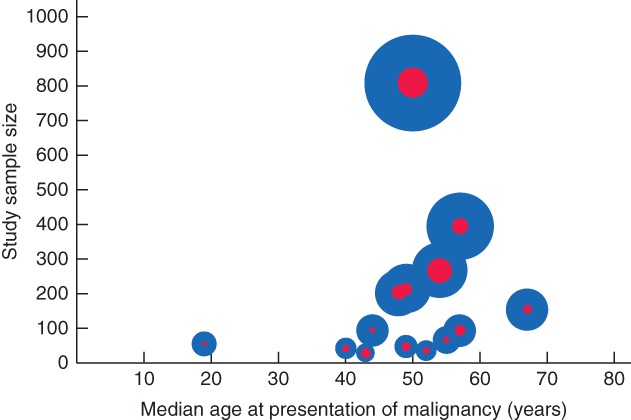

Six studies7, 22, 26, 32, 34, 38 (comprising 58 patients) provided detailed information on age at which malignancies developed. Of these 58 patients, 41 were aged less than 60 years. There was one 12‐year‐old child with a malignancy. The number of patients per age decade is shown in Fig. 3. Of the other 11 studies that reported the development of malignancies, only eight reported median age. The median age was less than 60 years in all but one of these studies23, 27, 28, 29, 30, 33, 37. The median age of patients with choledochal malformation at presentation of malignancy for each study is illustrated in Fig. 4. The median age at which malignancy developed was 49·5 years (14 studies); three studies31, 35, 36 lacked this information. One study25 reported no development of malignancy. The malignancy rates and median age at detection of malignancy are shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Age at development of malignancy in relation to prevalence of malignancy, and development of malignant transformation after drainage and after hepaticojejunostomy. Data from six studies7, 22, 26, 32, 34, 38 comprising 58 patients

Figure 4.

Median age of patients with choledochal malformation at presentation of malignancy in each study. The size of each blue circle indicates the study sample size, and that of each red circle the incidence of choledochal malformation, relative to that in the other studies

Type of choledochal malformation and development of malignancy

Thirteen studies7, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31, 34, 36, 38 (2304 patients) provided information about development of malignancies and type of choledochal malformation (Table 2). Malignancies were found during initial surgery in 167 patients. Of these, 153 had types I or IV choledochal malformation (91·6 per cent). Malignant transformation was found in 78 patients, almost exclusively among those with types I or IV malformations (77 of 78, 99 per cent) (P = 0·016). One patient with a type V malformation had malignant transformation. Types II and III were not associated with malignant transformation.

Table 2.

Development of malignancy by type of choledochal malformation

| Type of malformation | n | Total prevalence of malignancy | No malignancy at time of operation | Malignant transformation after drainage | Malignant transformation after complete cyst excision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I/IV | 2049 (88·9) | 153 (7·5) | 1896 | 42 (2·2) | 35 (1·8) |

| II/III | 59 (2·6) | 3 (5) | 56 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| V | 196 (8·5) | 11 (5·6) | 185 | 0 (0) | 1 (0·5) |

| Overall | 2304 | 167 | 2137 | 42 | 36 |

Type of resection and development of malignancy

A meta‐analysis including nine studies7, 23, 26, 30, 32, 35, 36, 37, 38 (1577 patients) was undertaken to investigate the influence of previous drainage procedures versus resection with hepaticojejunostomy as a risk factor for developing malignancy (Fig. 5). The remaining nine studies were not included in this analysis as they did not report malignant transformation22, 25, 27, 28, 33 or provided no information about the type of treatment24, 29, 31, 34. Of the 1574 patients, 1270 were treated with hepaticojejunostomy and 304 with some type of drainage procedure. Malignant transformation was found in 24 of 1270 patients who underwent hepaticojejunostomy and 56 of 304 treated with drainage (P < 0·001). Patients who underwent cystic drainage had an increased risk of developing biliary malignancy compared with those who underwent complete cyst excision, with an odds ratio of 3·97 (95 per cent c.i. 2·40 to 6·55). Eight studies7, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 38 provided information about the time interval between surgery and detection of malignancy (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing development of malignancy in patients treated with drainage procedures and compared with those who underwent complete cyst excision followed by a Roux‐en‐Y hepaticojejunostomy. A Mantel–Haenszel fixed‐effect model was used for meta‐analysis. Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals

Discussion

Choledochal malformation is considered a premalignant condition, even though scientific evidence in support of this is relatively scarce. The results of this systematic review and meta‐analysis showed that malignancies may develop in up to 11 per cent of patients with choledochal malformation. The risk of developing malignancy was four times greater among patients treated with drainage procedures rather than complete cyst excisions, especially those with types I or IV malformations.

Eighteen studies7, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 that reported on the development of malignancies in patients with choledochal malformation were identified in this review. The prevalence of malignancy was 7·3 per cent among patients with choledochal malformation and the rate of malignant transformation was 3·4 per cent. This finding implies that treating choledochal malformation may reduce the risk of developing malignancy, and is consistent with the commonly accepted theory that carcinogenesis might be related to dysplasia and metaplasia of the epithelium of the choledochal malformation6, 7, 8, 13. Complete cyst excision followed by construction of a bilioenteric anastomosis is therefore believed to protect the patient from developing malignancy39, 40. This also holds true for the other pathophysiological mechanisms that have been proposed, such as genetic deletions and heredity; thus surgical resection of the affected biliary tract remains the mainstay of therapy. Nevertheless, a malignant transformation rate of 3·4 per cent, mainly in patients who underwent drainage procedures, is a relatively high proportion. In the past, drainage procedures, whereby the cyst remained intact and surgery was limited to cystenterostomy, were popular. Such operations are no longer performed because of the assumed higher risk of developing malignancy6, 7. These assumptions were corroborated by the present finding that patients treated with drainage procedures had nearly a fourfold higher risk of malignancy compared with patients who underwent complete cyst excision. This implies that patients who have undergone drainage procedures are at increased risk of developing malignancies throughout their lives. Even though the overall postoperative complication rate of complete cyst excision followed by hepaticojejunostomy is between 15 and 20 per cent24, 40, this outweighs the poor prognosis if a malignancy develops, with a 5‐year survival rate of merely 5 per cent41. Therefore, it is recommended that patients who have undergone drainage procedures in the past be reoperated with complete cyst excision followed by hepaticojejunostomy.

No differences in the prevalence of malignancy between the different types of choledochal malformation were found in the present study. Patients who had surgery for choledochal malformation types I or IV had a significantly increased risk of malignant transformation compared with those with choledochal malformation types II or III. This difference may be related to the aetiology of the different types of choledochal malformation. It may be speculated that Todani types I and IV malformations are both associated with an abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction and that the prolonged reflux of pancreatic secretions into the biliary tract is not only responsible for the dilatation of the biliary tract, but might also lead to malignant degeneration42. However, based on the present data it cannot be confirmed or refuted that the presence of an abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction is a precondition for the development of carcinoma. A hyperplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence, as observed in the colon or oesophagus, was suggested based on pathological findings42. According to the Todani classification, type I choledochal malformation has no intrahepatic involvement and it is therefore illogical that malignant transformation could occur in the intrahepatic biliary tree after complete cyst excision. Malignant transformation in the intrahepatic biliary tree has, however, been reported in patients with type I choledochal malformation7, 24, 26, 29, 30, 38. This may be explained by the theory that types I and IV malformations are essentially the same lesions43. Malignant transformation in patients with types I and IV choledochal malformation could be associated with chronic inflammation of the biliary tree owing to (low‐grade) cholangitis29. As types II and III malformations are not associated with an abnormal pancreaticobiliary duct junction, they might have a different aetiology and a different malignant degeneration process, if such a process exists. Type V might be a completely different entity involving the intrahepatic ducts alone and often requiring a liver transplantation. Because of the higher risk of malignant transformation in patients with types I and/or IV choledochal transformations, it is of utmost importance to monitor these patients carefully.

Previous studies have invariably highlighted age as a possible risk factor. It is commonly accepted that the risk of malignancy increases with increasing age at presentation30, 44. Nicholl and colleagues44 reported a malignancy risk of zero among patients aged less than 30 years, compared with 50 per cent in patients older than 51 years. The present review found a similar trend, with a peak between 61 and 70 years. Even though the risk of developing malignancy increases with age, the results of this systematic review showed a strikingly younger age at which malignancy developed in patients with choledochal malformation (median 49·5 years) in comparison with the general cholangiocarcinoma population (median 65 years)41. This is 20 years younger than in the general population41. Therefore, when a choledochal malformation is confirmed, a complete cyst excision is warranted, even in an asymptomatic elderly patient.

The incidence of choledochal malformation is higher among patients of Asian descent, so most literature on malignant transformation refers to the Asian population. The limited data found in this review suggest a similar risk of developing malignancy among Asian and Caucasian populations. Although the incidence of choledochal malformation is higher in the Asian population, it seems that once a choledochal malformation is present the risk of developing malignancy is independent of ethnicity. Regarding patients without a choledochal malformation, the Asian population also has an increased baseline risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma compared with the Caucasian population41. This predisposition provides a clear argument in favour of there being a genetic background for the development of adenocarcinoma in abnormal epithelium. Caution should be exercised when interpreting the literature of mostly retrospective series, because the Asian and Caucasian populations are not comparable. Further research on malignant transformations in the Caucasian population is required. Caucasians represented 20 per cent of the patients in the present review; this proportion is too small for conclusions to be drawn about this population.

This systematic review and meta‐analysis is based on the results of 18 retrospective cohort studies, with wide variation in sample size (ranging from 10 to 808 patients), moderate study quality and likelihood of selection bias45. The overall quality of evidence according to the GRADE criteria19 had to be downgraded owing to sparse and imprecise data, and uncertainty about the baseline risk for the population of interest. However, this systematic review used current standards, including PRISMA, MOOSE and GRADE guidelines. By applying strict study quality and methodological assessment using the NOS for cohort studies, the best available evidence was extracted, which could be helpful in addressing this complex clinical problem. However, collaborative international initiatives such as the Biliary Atresia and Related Diseases database46 are instrumental in obtaining a more precise risk estimate for the development of malignancy in patients with choledochal malformation.

Acknowledgements

A.t.H. was supported partially by the Van Walree Grant of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Makin E, Davenport M. Understanding choledochal malformation. Arch Dis Child 2012; 97: 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turowski C, Knisely A, Davenport M. Role of pressure and pancreatic reflux in the aetiology of choledochal malformation. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 1319–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dhupar R, Gulack B, Geller DA, Marsh JW, Gamblin TC. The changing presentation of choledochal cyst disease: an incidental diagnosis. HPB Surg 2009; 2009: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kamisawa T, Okamoto A, Tsuruta K, Tu Y, Egawa N. Carcinoma arising in congenital choledochal cysts. Hepatogastroenterology 2008; 55: 329–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Todani T, Watanabe Y, Narusue M, Tabuchi K, Okajima K. Congenital bile duct cysts: classification, operative procedures, and review of thirty‐seven cases including cancer arising from choledochal cyst. Am J Surg 1977; 134: 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jordan PH, Goss JA, Rosenberg WR, Woods KL. Some considerations for management of choledochal cysts. Am J Surg 2004; 187: 790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lenriot JP, Gigot JF, Ségol P, Fagniez PL, Fingerhut A, Adloff M. Bile duct cysts in adults: a multi‐institutional retrospective study. French Association for Surgical Research. Ann Surg 1998; 228: 159–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Komi N, Tamura T, Tsuge S, Miyoshi Y, Udaka H, Takehara H. Relation of patient age to premalignant alterations in choledochal cyst epithelium: histochemical and immunohistochemical studies. J Pediatr Surg 1986; 21: 430–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ziegler KM, Pitt HA, Zyromski NJ, Chauhan A, Sherman S, Moffat D et al Choledochoceles: are they choledochal cysts? Ann Surg 2010; 252: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Imazu M, Iwai N, Tokiwa K, Shimotake T, Kimura O, Ono S. Factors of biliary carcinogenesis in choledochal cysts. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2001; 11: 24–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nagata E, Sakai K, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K. Choledochal cyst: complications of anomalous connection between the choledochus and pancreatic duct and carcinoma of the biliary tract. World J Surg 1986; 10: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsang TM, Tam PKH, Chamberlain P. Obliteration of the distal bile duct in the development of congenital choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg 1994; 29: 1582–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim Y, Hyun J, Lee J, Lee H, Kim C. Anomalous union of the pancreaticobiliary duct without choledochal cyst: is cholecystectomy alone sufficient? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2014; 399: 1071–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cheng SP, Yang TL, Jeng KS, Liu CL, Lee JJ, Liu TP. Choledochal cyst in adults: aetiological considerations to intrahepatic involvement. ANZ J Surg 2004; 74: 964–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. ten Hove A, de Kleine RH, Hulscher JBF, de Meijer VE. A Systematic Review on the Risk of Development of Malignancy in Congenital Choledochal Malformation http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016048392 [accessed 11 November 2017].

- 17. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non‐Randomized Studies in Meta‐analyses http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp [accessed 11 November 2017].

- 18. Oxford Centre for Evidence‐Based Medicine Levels of Evidence Working Group . The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evidence. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 [accessed 11 November 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Atkins D, Best D, Briss P, Eccles M, Falck‐Ytter Y, Flottorp S. GRADE Working Group . Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004; 328: 1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higgins J, Thompson S. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D et al Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta‐analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000; 283: 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moslim MA, Takahashi H, Seifarth FG, Walsh RM, Morris‐Stiff G. Choledochal cyst disease in a Western center: a 30‐year experience. J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 20: 1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xia HT, Yang T, Liang B, Zeng JP, Dong JH. Role of the surgical method in development of postoperative cholangiocarcinoma in Todani type IV bile duct cysts. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015; 2015: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soares KC, Kim Y, Spolverato G, Maithel S, Bauer TW, Marques H et al Presentation and clinical outcomes of choledochal cysts in children and adults: a multi‐institutional analysis. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Machado NO, Chopra PJ, Al‐Zadjali A, Younas S. Choledochal cyst in adults: etiopathogenesis, presentation, management, and outcome – case series and review. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2015; 2015: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. He XD, Wang L, Liu W, Liu Q, Qu Q, Li BL et al The risk of carcinogenesis in congenital choledochal cyst patients: an analysis of 214 cases. Ann Hepatol 2014; 13: 819–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Katabi N, Pillarisetty VG, Dematteo R, Klimstra DS. Choledochal cysts: a clinicopathologic study of 36 cases with emphasis on the morphologic and the immunohistochemical features of premalignant and malignant alterations. Hum Pathol 2014; 45: 2107–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mabrut J‐Y, Kianmanesh R, Nuzzo G, Castaing D, Boudjema K, Létoublon C et al Surgical management of congenital intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, Caroli's disease and syndrome: long‐term results of the French Association of Surgery Multicenter Study. Ann Surg 2013; 258: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohashi T, Wakai T, Kubota M, Matsuda Y, Arai Y, Ohyama T et al Risk of subsequent biliary malignancy in patients undergoing cyst excision for congenital choledochal cysts. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 28: 243–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee SE, Jang J‐Y, Lee Y‐J, Choi DW, Lee WJ, Cho B‐H et al Choledochal cyst and associated malignant tumors in adults: a multicenter survey in South Korea. Arch Surg 2011; 146: 1178–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takeshita N, Ota T, Yamamoto M. Forty‐year experience with flow‐diversion surgery for patients with congenital choledochal cysts with pancreaticobiliary maljunction at a single institution. Ann Surg 2011; 254: 1050–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cho M‐J, Hwang S, Lee Y‐J, Kim K‐H, Ahn C‐S, Moon D‐B et al Surgical experience of 204 cases of adult choledochal cyst disease over 14 years. World J Surg 2011; 35: 1094–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Huang CS, Huang CC, Chen DF. Choledochal cysts: differences between pediatric and adult patients. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14: 1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ono S, Fumino S, Shimadera S, Iwai N. Long‐term outcomes after hepaticojejunostomy for choledochal cyst: a 10‐ to 27‐year follow‐up. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45: 376–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu YB, Wang JW, Devkota KR, Ji ZL, Li JT, Wang XA et al Congenital choledochal cysts in adults: twenty‐five‐year experience. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007; 120: 1404–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wiseman K, Buczkowski AK, Chung SW, Francoeur J, Schaeffer D, Scudamore CH et al Epidemiology, presentation, diagnosis, and outcomes of choledochal cysts in adults in an urban environment. Am J Surg 2005; 189: 527–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu C‐L, Fan S‐T, Lo C‐M, Lam C‐M, Poon RT‐P, Wong J. Choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg 2002; 137: 465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ishibashi T, Kasahara K, Yasuda Y, Nagai H, Makino S, Kanazawa K. Malignant change in the biliary tract after excision of choledochal cyst. Br J Surg 1997; 84: 1687–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tao KS, Lu YG, Wang T, Dou KF. Procedures for congenital choledochal cysts and curative effect analysis in adults. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2002; 1: 442–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saing H, Han H, Chan KL, Lam W, Chan FL, Cheng W et al Early and late results of excision of choledochal cysts. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32: 1563–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mihalache F, Tantau M, Diaconu B, Acalovschi M. Survival and quality of life of cholangiocarcinoma patients: a prospective study over a 4 year period. J Gastroenterol Liver Dis 2010; 19: 285–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Søreide K, Søreide JA. Bile duct cyst as precursor to biliary tract cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 14: 1200–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Visser BC, Suh I, Way LW, Kang SM. Congenital choledochal cysts in adults. Arch Surg 2004; 139: 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nicholl M, Pitt HA, Wolf P, Cooney J, Kalayoglu M, Shilyansky J et al Choledochal cysts in western adults: complexities compared to children. J Gastrointest Surg 2004; 8: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Egger M, Schneider M, Davey Smith G. Spurious precision? Meta‐analysis of observational studies. BMJ 1998; 316: 140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peterson C. Biliary Atresia and Related Diseases. http://www.bard-online.com/ice/?domain=www.bard-online.com&fuseaction=extarticle&menu=2001&id=1637&lang=2 [accessed 11 November 2017]. [Google Scholar]