Abstract

Patient: Male, 64

Final Diagnosis: Meat bolus retention in cervical esophagus

Symptoms: Meat bolus impacted

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Cervical esophagotomy

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Voluntary and involuntary ingestion of foreign bodies is a common condition; in most cases they pass through the digestive tract, but sometimes they stop, creating emergency situations for the patient. We report a case of meat bolus with cartilaginous component impacted in the cervical esophagus, with a brief literature review.

Case Report:

A 64-year-old man came to our attention for retention in the cervical esophagus of a piece of meat accidentally swallowed during lunch. After a few attempts of endoscopic removal carried out previously in other hospitals, the patient has been treated by us with a cervical esophagotomy and removal of the foreign body, without any complications.

We checked the database of PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library from January 2007 to January 2017 in order to verify the presence of randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, retrospective studies, and case series regarding the use of the cervical esophagotomy for the extraction of foreign bodies impacted in the esophagus.

Conclusions:

The crucial point is to differentiate the cases that must be immediately treated from those requiring simple observation. Endoscopic treatment is definitely the first therapeutic option, but in case of failure of this approach, in our opinion, cervical esophagotomy could be a safe, easy, viable, durable approach for the extraction of foreign bodies impacted in the cervical esophagus. Our review does not have the purpose of providing definitive conclusions but is intended to represent a starting point for subsequent studies.

MeSH Keywords: Esophagostomy; Endoscopy, Digestive System; Foreign Bodies

Background

Foreign body (FB) ingestion and food bolus impaction are frequently seen in people of all ages [1]. Generally, they are avoidable, in children as well as in adults. About 80–90% of foreign bodies pass naturally and simply through the digestive tract, but a significant percentage impacts the upper aerodigestive tract [2]. Clinical situations are varied and the risk to the patient ranges from negligible to life-threatening. Diagnosis, treatment, and management strategies depend on multiple patient- and ingested object-related factors [3]. Initial failure to treat this important emergency can cause serious complications, significant morbidity, and mortality. Normally, occurrences such as esophageal perforation, mediastinitis, sepsis, or death are rare. In one series, the complications associated with foreign bodies impaction were reported to be ulcers (21.2%), lacerations (14.9%), erosions (12%), and perforation (1.9%) [4]. The treatment of choice is endoscopic retrieval, but when endoscopic attempts fail and the clinical condition deteriorates, surgery is necessary. We report a case of a patient with a meat bolus with cartilaginous component impacted in the cervical esophagus.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man reported that he ingested a piece of meat during lunch. After he swallowed this food bolus, he had symptomatology characterized by dysphagia and odynophagia. For this reason and for the persistence of symptoms, he went to the emergency department of another hospital and shortly thereafter underwent a gastroscopy. Esophageal endoscopy showed a foreign body in the upper third, which occupied the lumen and was impacted to the wall. Attempts at recovery and mobilization with endoscopic instruments (Dormia basket and forceps) were unsuccessful. Therefore, on the same evening, the patient was transferred to our department and immediately underwent laboratory tests, physical examination, computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, and further gastroscopy. His comorbidities were high blood pressure and insulin-dependent diabetes. The parameters measured at admission were blood pressure 180/100 mmHg, blood sugar 225 mg/dl, heart rate 86, and oxygen saturation 96%, and adequate therapy has begun. A second attempt of endoscopic removal was also unsuccessful because of the hard texture of the foreign body stuck in the esophageal wall. Moreover, the cartilage component of the meat bolus had created the first signs of pressure sores on the mucosa (Figure 1). The CT images, however, confirmed the presence of a foreign body with dimensions of 31×22 mm (Figure 2A, 2B). It showed a thickening of the esophageal wall and periesophageal adipose tissue, as well as absence of pneumomediastinum. Given the stable condition of the patient, the on the next morning a third attempt at endoscopic retrieval failed. As soon as possible, the patient was taken to the operating room and underwent surgery at about 23–24 hours after ingestion of the food bolus and the onset of symptoms. Surgery was by left side cervicotomy approach. After isolation of the cervical esophagus, a longitudinal esophagotomy was performed, resulting in extraction of the foreign body. We performed double-layer suturing of the esophageal opening, with drainage positioning and closing of the cervicotomy (Figure 3A–3C).

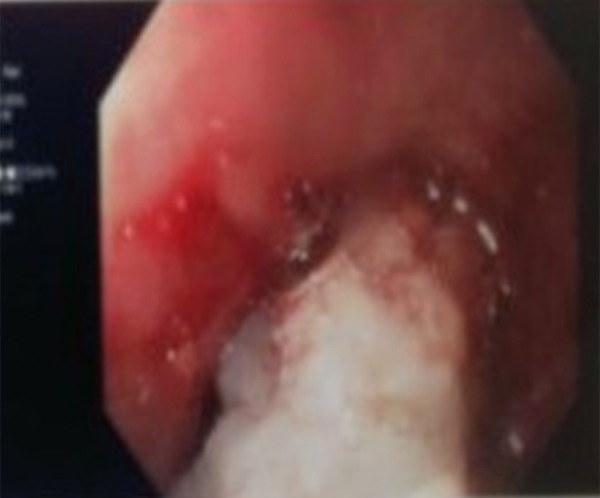

Figure 1.

Endoscopic image showing how the cartilage component of the foreign body is preponderant and causing a pressure sore on the esophageal mucosa.

Figure 2.

CT images show the foreign body in the sagittal (A) and axial (B) plane.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative images showing the extraction of the foreign body (A), the final suturing of esophagotomy (B), and the surgical specimen (C).

beginning on the day of the intervention, the patient fasted and received antibiotic therapy, parenteral nutrition, monitoring of nasogastric tube, and laboratory tests. On the first postoperative day, the blood exams showed leukocytosis with increased of white blood cells (WBC 18.03×103/uL), high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP 125.89 mg/dl), and a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR 87 mm/h). All these decreased and the values measured on the 8th postoperative day were WBC 7.6×103/uL, CRP 0.85 mg/dl, and ESR 76 mm/h. On the same day, a radiological examination with Gastrografin was performed. X-rays showed no contrast medium spreading. On the 9th day, antibiotic therapy and fasting were terminated and a liquid diet was begun, and on the day after the drainage tube was removed the patient began eating a solid diet. He was discharged 11 days after surgery, without any complications.

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library databases from January 1997 to January 2017 for randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, retrospective studies, and case series on the use of the cervical esophagotomy for the extraction of foreign bodies impacted in the esophagus, using the following search terms: foreign body extraction, foreign bodies extraction, cervical esophagotomy, and cervical esophagotomy. We only considered articles and reviews already published. We found 1204 records, and after the elimination of the repeated references, and based on the reading of the title and abstract in English language, only 9 were relevant and eligible, including a total of 49 patients (Table 1). The eligibility criteria were: experience with at least 3 cases, adult patients, lateral cervical approach with esophagotomy, cervical esophagus involvement, and previous flexible/rigid endoscopic examination. Due to insufficient sample size, we excluded reports with less than 3 clinical cases, and we rejected reports on children as they are unable to accurately communicate subjective symptoms.

Table 1.

Eligible studies in the last 20 years.

| Author | N. of cases (Total 49) | Comorbidities | Clinical manifestations | Types of foreign bodies | Complications after surgery | Postop. hospital stay (days) | Foreign bodies size (mm) | Time since ingestion (days) | Endoscopic unsuccessful causes | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peng A [5] | 16 | ND | 6 abscesses, 10 perforations | 6 dental prostheses, others ND | None | 31 (average on total of 121 patients | ND | ND | 6 caught in the esophageal wall, 10 not detected for extraluminal penetration | Adults |

| Sawayama H [6] | 7 | 4 dementia, 3 schizophrenia | 1 cough phlegm, 1 dyspnea, 1 odynophagia, 1 dysphagia, 1 fever, 2 denture loss, 2 perforations | 7 partial dentures with sharp clasps | 3 tracheostomies | 23.86 | 54×36 mm | ND | 7 clasps invaginated in the esophageal mucosa | Adults |

| Yadav R [7] | 5 | ND | ND | 5 dental plate with hooks | None | 7+2 | ND | 4.8+1.92 | 5 caught in the esophageal wall | Adults |

| Okugbo SU [8] | 3 | ND | ND | 3 dentures | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Adults |

| Toshima T [9] | 3 | 1 schizophrenia, 1 brain paralysis, 1 cerebral hemorrhage sequelae | 1 odynophagia and precordialgia, 1 perforation | 3 dentures with sharp clasps | None | ND | ND | ND | 2 caught in the esophageal mucosa, 1 caught in the esophageal wall | Adults |

| Orji FT [10] | 3 | ND | ND | 1 metal beer-bottle cap, 1 large denture, 1 fish hook | None | ND | ND | ND | 3 caught in the esophageal wall | ND |

| Nwaorgu OG [11] | 3 | ND | 3 perforations | 3 dentures | ND | ND | ND | 4 (mean duration before presentation) | 3 failed extraction via rigid esophagoscopy | Adults |

| Al-Sebeih K [12] | 6 | ND | 5 dysphagia, 2 neck pain, 1 mild trismus, 1 fever, 2 right neck swelling, 1 left neck swelling, 1 edema of hypopharynx, 4 abscesses, 6 perforations | 5 fish bone, 1 steel wire | ND | ND | ND | <1–5 | 6 no evidence of intraluminal foreign bodies for extraluminal penetration | Adults |

| Predescu D [13] | 3 | No | 3 perforations, 3 abscesses | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | Adults |

ND – not detectable.

Discussion

Voluntary or involuntary esophageal ingestion of foreign bodies are more frequent than those of the airways. About 80–90% of these migrate in the lower digestive tract and are eliminated naturally, while approximately 10–20% require endoscopic extraction, and only 1% of cases need surgery [14,15]. The esophagus is the most frequent site of blockage [16]. The arrest of a foreign body in this location is due to the presence of narrowing of the lumen. These can be both anatomical and pathological in nature (organic or functional). In the esophagus there are 4 physiological constrictions: the cricopharyngeal sphincter, aortic arch, left main bronchus, and diaphragmatic hiatus. There can also be benign (e.g., mucosal ring, atresia, inflammatory stricture, and post-surgical) or malignant stenosis and functional disorders such as achalasia or other dyskinesias [17,18]. Patients may be asymptomatic, symptomatic, or present complications. The risk of complication is 25% higher in the upper esophagus than in other sites, and the proximity of vital organs around the esophagus makes many complications life-threatening [19,20]. Common clinical signs are dysphagia, odynophagia, hypersialorrhea, low cervical or chest strain, vomiting, and dyspnea if there is tracheal compression. Complications occur in the late stage when the obstruction, erosion, or infection cause mucosal ischemia and necrosis resulting from prolonged impaction, but also during or after removal. There are many serious complications, including perforation, retropharyngeal abscess, mediastinitis, fistula [21], pneumothorax, hydrothorax, pneumomediastinum, and aspiration. In these cases, morbidity and mortality are relatively high. Related risk factors for complications are time interval over 24 h between ingestion and presenting to the emergency department, positive radiographic findings, age >50 years [22], involvement of the upper third of the esophagus, symptoms of complete digestive or respiratory obstruction, and high-risk objects due their shape, size, and composition [23].

After history-taking and physical examination, the next step is radiological assessment to complete the diagnosis and acquire more information on which to determine the therapeutic procedure. Radiological assessment is important because shows the location and nature of the foreign body. Neck, chest, and abdominal imaging studies (simple X-ray or CT) should be performed in anteroposterior and lateral views. These radiographic examinations are also essential to evaluate, size, shape, number, and plan removal approach. A significant role of radiology is in recognition of complications, possibly showing mediastinal, subdiaphragmatic, or subcutaneous air or pleural effusion [24], thickening of the soft cervical-mediastinal tissues, and presence of prevertebral emphysema [25], all suggesting perforation. CT is recommended as soon as possible within the first 24 hours [26]. It is important to consider that food or meat bolus, which are the most frequent causes of impaction in adults, are not always detectable radiologically unless bone and cartilaginous tissue is present. The utility of MRI is limited.

Above all, if the clinical results are not available or are inconclusive, the correct diagnosis can be achieved by means of direct evaluation of the aerodigestive tract through endoscopy, which has diagnostic and therapeutic value, and it is at present considered the criterion standard for use in these cases. Rigid and flexible esophagoscopy are possible and they have high diagnosis rates [27]. Endoscopy should be carried out whenever trained personnel are available, the instruments are ready, a full range of retrieval accessories is available [28], and the techniques have been tested. In fact, in the hands of an experienced endoscopist, the explorations in a very limited work space and where underlying diseases are frequent and sometimes unknown at the time of procedure, allows to obtain diagnostic informations and to perform a therapeutic gesture with finesse, patience and safety of handling. Endoscopic attempts by experienced medical teams carefully avoid a blind push of the food bolus towards the stomach, and often achieve good results after other less experienced teams have failed. Using a flexible forward-viewing endoscope increased the successful rate to >90% of cases with an approximate <5% complication rate [29]. Considering that delay in the removal of esophageal impacted foreign bodies is potentially harmful, and all of them have to be removed within 24 hours [30], the failure of one or more endoscopic attempts in a patient whose clinical situation is already critical and complicated at the time of admission, in these situations emergency surgery is mandatory. The surgical approach depends on the location of the perforation (e.g., left lateral cervicotomy along the sternocleidomastoid muscle, right thoracotomy in space IV, V, VI, left distal thoracotomy or laparotomy for impaction in distal esophagus), the nature of the foreign body, and the severity of mediastinal necrotic or inflammatory response evaluated by CT scan [31]. Surgery is not a defeat for the endoscopist, but instead is the best treatment for the patient when retrieval was not achieved by other methods or when the patient developed complications. Perforations can undergo primary repair for early detection or diversion of the esophagus in the most serious cases. A perforation is usually an indication for surgery, but some authors have treated it successfully with conservative treatment [32]. Extraluminal migration is always an indication for surgery [33].

During the analysis of the 9 articles we considered eligible, we found some favorable conditions for a surgical approach. In most cases, endoscopic failure was the main cause. Moreover, failure of endoscopic removal was mainly due to the presence of abscess and/or perforation, prolonged time since ingestion, and the type and size of the foreign body, increasing the likelihood of need for surgical treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conditions leading to surgical approach.

| Endoscopic failure | ||

| • caught in the esophageal wall | 24/49 | |

| • failed extraction via rigid esophagoscopy | 3/49 | |

| • extraluminal penetration | 16/49 | |

| • others ND | 6/49 | |

|

| ||

| Associated clinical manifestations | ||

| • abscesses | 13/49 | |

| • perforation | 25/49 | |

| • edema of hypopharynx | 1/49 | |

| • neck swelling | 3/49 | |

| • dysphagia | 6/49 | |

| • neck pain | 2/49 | |

| • mild trismus | 1/49 | |

| • fever | 2/49 | |

| • odynophagia | 2/49 | |

| • precordialgia | 1/49 | |

| • denture loss | 2/49 | |

| • cough phlegm | 1/49 | |

| • dyspnea | 1/49 | |

|

|

||

| Time since ingestion | ||

| • 4.8+1.92 d | 5/49 | |

| • 4 d | 3/49 | |

| • <1–5 d | 6/49 | |

| • others ND | 35/49 | |

|

|

||

| F.B. size | ||

| • 54×36 mm | 7/49 | |

| • others ND | 42/49 | |

|

|

||

| F.B. type | ||

| • dental prostheses | 28/49 | |

| • fish bone | 5/49 | |

| • steel wire | 1/49 | |

| • fish hook | 1/49 | |

| • metal beer-bottle cap | 1/49 | |

| • others ND | 13/49 | |

ND – not detectable; F.B. – foreign body; d – days.

Conclusions

In conclusion, foreign body ingestion and stoppage in the esophagus is a frequent emergency which causes functionally mild or severe symptoms. The crucial point is to differentiate those that must be immediately removed from those requiring simple observation. Urgent treatment is required if the patient has breathing problems and cannot swallow saliva, because of high risk of inhalation. Removal of an impacted food bolus must be performed in all cases within 12–24 hours endoscopically at first or then surgically [34], as in our case. In most series, the success rate of endoscopic treatment of food bolus impaction from the upper digestive tract is around 95% [16,18]. Our opinion, like that of other authors, is that cervical esophagotomy can be a safe, easy, viable, durable approach for extraction of foreign bodies, especially in cases when an endoscopic approach was not successful and the risk of complications is high. Surgery can be life-saving and usually has only minor postoperative complications if it accompanied by effective antibiotic therapy. Our review did not intend to provide definitive conclusions, but instead represents a starting point for subsequent studies.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, et al. 2007 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 25th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:927–1057. doi: 10.1080/15563650802559632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MT, Wong RK. Esophageal foreign bodies: Types and techniques for removal. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2006;9:75–84. doi: 10.1007/s11938-006-0026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sahn B, Mamula P, Ford CA. Review of foreign body ingestion and esophageal food impaction management in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:260–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung SH, Jeon SW, Son HS, et al. Factors predictive of risk for complications in patients with oesophageal foreign bodies. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:632–35. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng A, Li Y, Xiao Z, Wu W. Study of clinical treatment of esophageal foreign body-induced esophageal perforation with lethal complications. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269:2027–36. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-1988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawayama H, Miyanari N, Morita K, et al. Surgical management of partial dentures in the cervicothoracic esophagus. Esophagus. 2016;13:270–75. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav R, Mahajan G, Mathur RM. Denture plate foreign body of esophagus. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;24:191–94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okugbo SU, Onyeagwara NC. Oesophageal impacted dentures at the University of Benin teaching hospital, Benin city, Nigeria. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2012;2:85–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toshima T, Morita M, Sadanaga N, et al. Surgical removal of a denture with sharp clasps impacted in the cervicothoracic esophagus: Report of 3 cases. Surg Today. 2011;41:1275–79. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orji FT, Akpeh JO, Okolugbo NE. Management of esophageal foreign bodies: Experience in a developing country. World J Surg. 2012;36:1083–88. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nwaorgu OG, Onakoya PA, Sogebi OA, et al. Esophageal impacted dentures. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:1350–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Sebeih K, Abu-Shara KA, Sobeih A. Extraluminal perforation complicating foreign bodies in the upper aerodigestive tract. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119:284–88. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Predescu D, Predescu I, Sarafoleanu C, Constantinoiu S. Oesophageal foreign bodies – from diagnostic challenge to therapeutic dilemma. Chirurgia (Bucur) 2016;111:102–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Webb WA. Management of foreign bodies of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Update. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:39–51. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70274-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiland ST, Schurr MJ. Conservative management of ingested foreign bodies. J Gastrointest Surg. 2002;6:496–500. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosca S, Manes G, Martino R, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: Report on a series of 414 adult patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:692–96. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-16212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirchner GI, Zuber-Jerger I, Endlicher E, et al. Causes of bolus impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3170–74. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1681-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li ZS, Sun ZX, Zou DW, et al. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper-GI tract: experience with 1088 cases in China. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:485–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokar B, Cevik AA, Ilhan H. Ingested gastrointestinal foreign bodies: Predisposing factors for complications in children having surgical or endoscopic removal. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:135–39. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1819-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Liu J, Li J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of 32 cases with aortoesophageal fistula due to esophageal foreign body. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:267–72. doi: 10.1002/lary.21366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loh KS, Tan LK, Smith JD, et al. Complications of foreign bodies in the esophagus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:613–16. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hung CW, Hung SC, Lee CJ, et al. Risk factors for complications after a foreign body is retained in the esophagus. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:423–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodríguez H, Passali GC, Gregori D, et al. Management of foreign bodies in the airway and oesophagus. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(Suppl. 1):S84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinto A, Muzj C, Gagliardi N, et al. Role of imaging in the assessment of impacted foreign bodies in the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2012;33:463–70. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berreta J, Kociak D, Ferro D, et al. Mediastinis related to esophagogastric disease and injury. Warning clinical signs and independent predictors of intrahospitalary survival. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2010;40:32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu YC, Zhou SH, Ling L. Value of helical computed tomography in the early diagnosis of esophageal foreign bodies in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1328–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gmeiner D, von Rahden BH, Meco C, et al. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy for treatment of foreign body impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2026–29. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bounds BC. Endoscopic retrieval devices. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;8:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen T, Wu HF, Shi Q, et al. Endoscopic management of impacted esophageal foreign bodies. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:799–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ginsberg GG. Management of ingested foreign objects and food bolus impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70273-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vallböhmer D, Hölscher AH, Hölscher M, et al. Options in the management of esophageal perforation: Analysis over a 12-year period. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:185–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herranz-Gonzalez J, Martinez-Vidal J, Garcia-Sarandeses A, Vazquez-Barro C. Esophageal foreign bodies in adults. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105:649–54. doi: 10.1177/019459989110500503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brady PG. Esophageal foreign bodies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:691–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1085–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]