Abstract

Over the last thirty years, the management of Malignant Ureteric Obstruction (MUO) has evolved from a single disciplinary decision to a multi-disciplinary approach. Careful consideration must be given to the risks and benefits of decompression of hydronephrosis for an individual patient. There is a lack of consensus of opinion as well as strong evidence to support the decision process. Outcomes that were identified amongst patients undergoing treatment for MUO included prognosis, quality of life (QOL), complications, morbidity and prognostication tools. A total of 63 papers were included. Median survival was 6.4 months in the 53 papers that stated this outcome. Significant predictors to poor outcomes included low serum albumin, hyponatremia, the number of malignancy related events, and performance status of 2 or worse on the European cooperative cancer group. We propose a multi-centre review of outcomes to enable evidence-based consultations for patients and their families.

Keywords: Clinical, end of life decisions (palliative care), oncology, palliative care, urological cancer, urology

Introduction

Malignant ureteric obstruction is a condition that affects patients with advanced stages of cancer. An obstructed single system can significantly reduce patients’ quality of life especially if infection ensues; however, bilateral obstruction will lead to a certain death. In fact, upper urinary tract obstruction is a prognostic indicator of morbidity for many cancers.1–3

Over the last 30 years, the management has evolved from a single disciplinary decision to a multi-disciplinary approach involving urologists, oncologists, palliative care physicians, general medicine physicians and interventional radiologists. This is mainly due to the fact that advanced stages of cancer is now treated with this multi-disciplinary approach; in addition, the surgical approach to malignant ureteric obstruction has evolved from predominantly highly morbid open surgical procedures4 to minimally invasive techniques.5 Brin et al. described their ‘disappointing’ experiences of open palliative procedures with patients suffering ‘an inexorable downhill course’.6 Interestingly, oncologists are more likely to push for decompression in asymptomatic patients with a poor prognosis than urologists.7

Individualised consideration must be given to the risks and benefits of decompression.6,8–12 Although there are recommendations within cancer-specific guidelines, both the European Association of Urology and the American Urological Association guidelines recommend decompressing the urinary systems,13,14 there is a lack of consensus of opinion as well as strong evidence to support the decision process.2,4,16,17 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines concluded that patients should be offered decompression, but that the option of ‘no intervention should also be discussed’. They noted that there was insufficient low-grade evidence in this arena.16,17 None of these recommendations take into consideration the implications of quality of life.

To this end, we aimed to conduct a review of the literature to be able to inform the decision-making process of managing patients with malignant ureteric obstruction. Specifically, we aim to distil the relevant evidence in this paper to help facilitate an evidence-based consultation with patients and their families on prognostic outcomes of decompression in the setting of malignant ureteric obstruction.16

Methods

Search strategy

The review was conducted using Cochrane and PRISMA guidelines.17–19 The search strategy included the following databases: the US National Library of Medicine’s life science database (MEDLINE) (1975–September 2017), EMBASE (1975–September 2017), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials – CENTRAL (in The Cochrane Library – 2017), CINAHL (1975–September 2017), Clinicaltrials.gov, Google Scholar and individual urological journals.

Search terms used included: ‘malignant ureteric obstruction’; ‘percutaneous nephrostomy’; ‘stent’; ‘quality of life’; and ‘prognosis’.

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) phrases included:

((“Stents”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Quality of Life”[Mesh]

(((“Stents”[Mesh]) AND “Ureter”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Quality of Life”[Mesh]

(((“Stents”[Mesh]) AND “Ureteral Obstruction”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Quality of Life”[Mesh]

(((“Stents”[Mesh]) AND “Ureteral Obstruction”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Prognosis”[Mesh]

((“Nephrostomy, Percutaneous”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Quality of Life”[Mesh]

(((“Nephrostomy, Percutaneous”[Mesh]) AND “Ureteral Obstruction”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Prognosis”[Mesh]

(((“Nephrostomy, Percutaneous”[Mesh]) AND “Ureteral Obstruction”[Mesh]) AND “Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Quality of Life”[Mesh]

Study selection

Three authors (JP, TA and OA) independently completed the review of literature independently and followed predefined inclusion criteria. Disagreement between the authors in study inclusion was resolved by consensus.

Inclusion criteria

All types of publications were included. Manuscripts involving adult patients (18 years old and above) with malignant ureteric obstruction in the English language were included. If only abstracts were available, these were included if sufficient data were extractable. We included papers reporting on benign disease if the data could be extracted separately.

Our outcome measures were:

Prognosis in patients diagnosed with malignant ureteric obstruction (across all tumour groups) who received decompression via percutaneous nephrostomy or ureteric stenting;

Quality of life associated with the above;

Major and minor complications;

Morbidity defined as hospitalisation post intervention;

Effect of decompression on renal function;

Prognostication tools in use to predict poor outcomes from intervention.

Data extraction

Data of each included study were independently extracted initially by two authors (JP and TA) after which a senior author (OA) extracted the data independently and cross-checked data extraction to ensure quality assurance of data. Data were tabulated using Microsoft Excel and inbuilt formulae utilised.

The following variables were extracted from each study: number of patients; gender; intervention; age; primary diagnosis; median survival; complications; amount of time spent in hospital; proportion of lifetime spent in hospital; proportion of patients not discharged; mortality, prognostication (where available); and quality of life.

Results

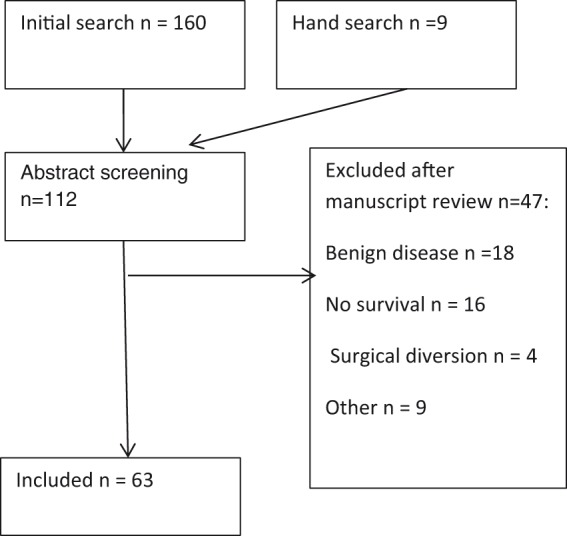

The initial review yielded 169 papers (see Figure 1). Of these, 54 were excluded after abstract screening and 47 were later excluded after full manuscript review. Of the 47 papers excluded, 18 papers included benign causes, 16 had no survival data, four used surgical diversion techniques and one paper excluded patients with poor outlook. Four were not available in the English language. Three authors were contacted to obtain manuscripts but did not respond. In total, 63 papers were included in the review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Characteristics of included studies

Seventeen studies were from United States of America, 14 from the United Kingdom, seven from Japan, five from Brazil, three from Germany, two from Greece, two from Korea. There was one paper authored from Serbia, the Philippines, Singapore, China, Pakistan, Jordan, Turkey, Israel, Sweden, New Zealand, Australia and Austria.

Only nine studies were prospective in nature; of these, one was a prospective cohort study. There were no randomised controlled trials. The follow-up period ranged from six months to eight years.

Demographics

In total, 4948 patients were included in this study.1,3,8–11,16,20–44,44–63 Of these, 1030 patients had stents and 3891 had nephrostomies. Most papers classified patients by individual tumour type (Table 1).1,3,8–11,16,20–44,44–64 The mean age of patients was 60 years (range: 19–97 years).1,3,8–11,16,20–26,28,29,32,33,35–39,41–43,45,48–50,52–54,56–58,60,61,63,64

Table 1.

Distribution of cancers.

| Type of cancer | No. of patients included |

|---|---|

| Prostate | 1561 |

| Cervical | 829 |

| Bladder | 533 |

| Colorectal | 473 |

| Gastrointestinal | 300 |

| Uterine | 64 |

| Other | 605 |

Prognosis

Fifty papers included prognosis as an outcome measure with a total of 2790 patients included. This ranged from 21 h to 140 months with a median survival of 6.4 months.1,3,8–11,16,20–44,44–53,55,57–60,62–65

Eight papers provided a mean one-year survival; the aggregate mean of the percentage of patients surviving one year was 23%.3,9,10,24,25,29,33,39,45

Quality of life

Twenty papers assessed quality of life with a total of 824 patients.9,11,12,20–23,25,28,31,33,45,46,49,50,61,62,66–68 Measures included time spent in hospital, pain assessment and qualitative interviews.

Five studies used the Grabstald outcome measure tool (167 patients).20,21,50,62,67,69 A cumulative analysis which found that 60% of patients were able to achieve a ‘useful life’ post decompression (Table 2).

Table 2.

Papers using Grabstald ‘useful life measure’.

| Paper | Type | Date | Number and male/female average age | Tumour type | Stent/nephrostomy (N patients) | Grabstald percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hubner et al.50 | Retrospective | 1986–1989 | 52 (31 F, 21 M) 67 (43–81) | Prostate 7% Bladder 25% Colorectal 28% Cervix 17% Ovarian 11% Other 2% | Stent 24, PCN 28 | 81% |

| Hoe et al.62 | Retrospective | Not stated | Not stated | Colorectal 33% Cervix 5% Prostate 5% Bladder 5% Rest not stated | PCN 24 | 46% |

| Emmert et al.20 | Retrospective | 1990–1995 | 24 45.9 (30–79) | Cervical 100% | PCN 24 | 46% |

| Feng et al.67 | Retrospective | 1984–1996 | 37 (20 F, 17 M) 37–85 No mean | Prostate 27% Bladder 13% Colorectal 10% Cervix 32% Uterus 5% Ovarian 10% | Stent 22, PCN 15 | 82–87% classified into two groups |

| Wilson et al.21 | Retrospective | 1996–2001 | 32 (16 M, 16 F) 68.1 (42–84) | Prostate 28% Bladder 25% Colorectal 21% Cervix 15% Uterus 6% Breast 3% | PCN 32 | 46.9% |

Two studies used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy concerning nephrostomy insertion and nephrostomy vs. stent insertion (Table 3). Neither had a significant difference between the groups. One study used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.61 There was no significant difference in quality of life when administered pre- and post-nephrostomy insertion (Table 3) Aravantinos et al. used the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire.61 There was no significant difference in quality of life when administered pre and post nephrostomy insertion.

Table 3.

Quality of life.

| Author | Patient details | Assessment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aravantinos et al.61 | 207 patients Bladder, prostate, cervical, gynaecological | EORTC-QOLC –C30 | No significant difference in QOL when administered pre and post nephrostomy insertion. |

| Monsky et al.66 | 46 patients (13 lost to follow-up) Bladder 14, cervical 15, prostate 6, uterine 5, Other 7 PCN = 15 Stent = 31 | FACT-BL | No statistical differences in patients’ responses post stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy insertion. Patients with stents reported significantly greater pain and storage lower urinary tract symptoms, although this did not translate into a reduction in measured QOL. |

| Lapitan et al.25 | 198 patients Cervical cancer | FACT-G | There was no statistical difference in the FACT-G scores for patients with or without percutaneous nephrostomy |

| Bigum et al.12 | 10 patients (prostate 8, bladder cancer 2) All nephrostomy | Qualitative interview | Main themes: Lack of follow-up, complications, physical limitations and the impact on their social life |

| Kumar et al.68 | 17 patients All percutaneous nephrostomy Ovary 6, uterine 3, cervical 2 | Qualitative interview | Main themes: Symptoms from decompression, an educational void and the role of self education (30% no symptoms) |

PCN: percutaneous nephrostomy; QOL: quality of life.

Complications

Twenty-four of the papers commented on the frequency of complications with a total of 1891 patients. The overall complication rate was 41%.10,11,16,22,23,26,32,33,36,39,45,51,59

Twenty-six per cent (439/1658) of patients with nephrostomies developed urinary infection, while 14% (26/180) of patients with stents placed developed infections. Ten per cent (173/1658) of patients experiencing dislodged nephrostomies, while 7% (113/1658) of patients developed blocked nephrostomies. Stent migration/dislodgement was reported in 6% (10/180). Haematuria rate was 8% (15/180) in patients stented compared to 3% (49/1658) in patients with nephrostomies. Nephrectomy rate was 0.2% (4/1658) following percutaneous nephrostomy placement; two for perinephric abscess (the indication for the other two patients was not stated).32,33 Mortality rate was 0.2% (4/1658): three from haemorrhage and one from sepsis. In the three papers that reported mortality, the overall rate was 5% (4/82).22,52,62

Twelve papers (628 patients) calculated the proportion of patients who never left hospital post decompression,9,11,21–23,28,31,33,45,55,62,64 with the pooled mean for this being 26% (range: 5–69%). Patients spent 20% of their remaining lifetime in hospital.8,23,28,33,37,44,45,48,49,53,62,64 Twelve papers included renal function pre and post procedure (a total of 1135 patients). Pre-nephrostomy, the average creatinine was 624 mmol/L and post procedure, the creatinine improved to 212 mmol/L on average.9,10,21,23,31,43,44,49,54,60,61,70

Prognostication tools

Sixteen papers with a total of 2061 patients investigated various factors and their ability to prognosticate3,9,10,24,25,28,30,31,36,38,42,54,61,71–73 in these patients (Table 4).

Table 5.

Proposed prognostication tool (PALLIATE).

| Performance status (ECOG2) |

| Albumin (low) |

| Low serum sodium |

| Laterality |

| Inflammatory markers (CRP) |

| Ascites |

| Tumour type |

| Events related to cancer (pleural effusions, metastatic disease) |

Table 4.

Summary of literature on prognostication.

| Paper | Study type | N | Age (range) | Process | Tumour type (%) | Features of poor outcome (statistically significant) | Survival based on predictors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feuer et al.54 | Prospective | 22 | 58 (n/a) | Univariate, Kaplan-Meyer | Cervical 77 Gynaecological (other) 18 Uterine 4 | Patients having one of: progressive tumour, performance status > 2, tumour-related medical problems, no treatment, uncontrolled pain | Survival 242 days (if 0 factors) vs. 37 days (if 1 or more factor) Days at home 164 days (if 0 factors) vs. 37 days (if 1 or more factor) |

| Watkinson et al.72 | Retrospective case series | 50 | 53 | Grouping – no statistical analysis | Cervical 32 Bladder 36 Colon 10 Lymphoma 4 Ovary 4 Other 6 | Not identified | 12-month survival Group I – benign or treated (100%) Group II untreated malignancy (50%) Median survival 339 days Group III ureteric obstruction by abdominopelvic disease with treatment (50%) Median survival 334 days Group IV ureteric obstruction by abdominopelvic disease without treatment (0%) Median survival 38 days |

| Wong et al.28 | Retrospective case series | 102 | 62 (31–86) | Univariate and multivariate analysis Kaplan-Meyer | Gastric 20 Gynaecological 31 Urological 29 Other 18 | Presence of metastatic disease Diagnosis of MUO in presence established malignancy | 12-month survival 63% in favourable (0–1 unfavourable factors) 12% in unfavourable (4 unfavourable factors) |

| Jeong et al.24 | Retrospective case series | 86 | 54 (23–79) | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Gastric 33, Cervical 10 Colorectal 40, Prostate 0, Bladder 0, Other 17 | ECOG 2 or more Lesion in upper ureter No treatment options post nephrostomy | No prognostication tool suggested |

| Aravantinos et al.61 | Retrospective | 507 | 63 (40–85) | Kaplan-Meyer curves and Mann-Whitney for QOL | Bladder 32 Prostate 26 Colorectal 17 Gynaecological 13 Other 8 gastric/pancreatic 3 | Disseminated disease (significant for prostate and colorectal cancer only) | All patients six-month survival 33% survival > 6 months |

| Ishioka et al.10 | Prospective | 140 | 57 (31–85) | Multivariate analysis Kaplan-Meyer | Gastric 21, Cervical 21 Urothelial 9, Colorectal 24, Other 10 | 3 or more cancer-related events Low serum albumin Low-grade hydronephrosis | Six-month survival 69% in favourable group (0 risk factors) Intermediate group 24% (1 risk factor) Poor group 2% (2–3 risk factors) |

| Lienert et al.36 | Retrospective | 49 | 71 (36–91) | Univariate | Cervical 6 Colorectal 12 Bladder 36, Prostate 30 Other 14 | Three or more cancer-related events Low serum albumin Low serum sodium | Mean survival in months 9 months for 0 risk factors 5.7 months for1 risk factor 2 Months for 2 or 3 risk factors |

| Jalbani et al.31 | Prospective | 40 | No average (21–70) | Paired T | Cervical 37 Rectum 7 Bladder 25, prostate 12 Rectum 7 | None identified | Good prognostic features Recent diagnosis Age < 52 |

| Izumi et al.38 | Retrospective | 61 | 64 (27–89) | Univariate and multivariate analysis | Gastric 24 Cervical 26 Colorectal 12, ovarian 9 Bladder 3 Prostate 5 | High creatinine (>106 µmol/L) No treatment options Non-gynaecological cancer | Survival in months Good predictors 13.2 months Intermediate 8.2 months Poor 1.7 months |

| Migita et al.3 | Retrospective | 25 | 61 | Multivariate analysis Kaplan-Meyer | Gastric 100 | No treatment options | Survival 3.1 months if no treatment options 11.2 months if treatment options |

| Azuma et al.30 | Retrospective | 214 | 79% < 80 21% > 80 | Multivariate | Gastric 16 Cervical 15 Colorectal 21 Urothelial 15 Prostate 14 Other 28 | Number event related to malignant dissemination Low serum albumin Low serum sodium High CRP | Median survival 12 months, Favourable (0–1 risk factors) 6 months, Intermediate (2 risk factors) 2.6 months, Poor group (3 risk factors) |

| Souza et al.56 | Retrospective | 48 | 59 (6–85) | Univariate Multivariate analysis | Cervical 100 | Haemoglobin < 8.7 g/dL Haematocrit < 27% Hypotension (in absence of sepsis) | Not calculated Compared characteristics of group who died compared with survival group |

| Alawneh et al.42 | Retrospective | 211 | 59 (6–85) | Multivariate analysis Kaplan-Meyer | Gastrointestinal 28 Genitourinary 58 Other 13 | Presence of ascites, pleural effusion, low serum albumin, bilateral hydronephrosis gastrointestinal malignancy | 12-month survival 0 factors 78%, 1 factor 36% 2 factors 17%, 3 factors 6% |

| Cordeiro et al.9 | Prospective | 208 | 61 (19–89) | Multivariate analysis Kaplan-Meyer | Cervical 20 Colorectal 21 Bladder 22 Prostate 12 | Number malignant events > or equal to 4 ECOG > or = 2 | 12-month survival Favourable (0 factors) 45% Intermediate (1 factor) 15% Unfavourable (2 factors) 7% |

| Downey et al.71 (abstract only) | Retrospective | 86 | – | Grouping – no statistical analysis | Bladder 35 No further data | Not identified | 12-month survival (based on Watkinson et al.72) Group I (non-malignant) no data Group II (untreated primary) 20%, Group III (relapsed disease viable option) 16% Group IV (no treatment option) 0% |

| Gandiya et al.73 (abstract only) | Retrospective | 193 | 70 (26–90) | Multivariate analysis Kaplan-Meyer | Urological 47, gynaecological 22 Colorectal 11, other 20 | Low serum albumin ECOG > or = 2 Prior oncological treatment | Pooled survival 82% survival at one month 63% at three months 50% survival at six months |

ECOG: European Cooperative Cancer Group; MUO: malignant ureteric obstruction; QOL: quality of life.

Most commonly occurring statistical significance included low serum albumin,10,30,36,42,73 no further treatment options,3,24,38,54 hyponatraemia,30,36 number of malignancy-related events (pleural effusion, metastatic disease, ascites),10,30,36,42 the presence of metastatic disease,28,61 performance status of 2 or worse on the European Cooperative Cancer Group.9,24,54,73

Patients with a malignancy of unknown primary or gastrointestinal origin were identified as having poorer outcomes,28,42 whereas gynaecological malignancies had a better outcome.38 Other variables included patients with upper ureteric obstruction,24 moderate–severe hydronephrosis,25 bilateral hydronephrosis,42 elevated creatinine,25,38 anaemia56 and patients with an elevated C-reactive protein.30

Discussion

This review of 63 papers gives a broad survival range for patients with malignant ureteric obstruction between 21 hours and 140 months.1,3,8–11,16,20–44,44–53,55,57–60,62–64 The median survival was 6.4 months and the percentage of patients alive at one year was 23%.3,9,10,24,25,29,33,39,45 Reasons for this variation in survival include the heterogeneous patient and cancer groups involved. Additionally, the data are limited by the fact that researchers in some instances may have included patients with retroperitoneal fibrosis secondary to treatment (such as radiotherapy) rather than ongoing or recurrent disease.74,75 The benign nature of this aetiology for obstruction would skew results towards improved outcomes. The majority of the papers reported on patients who underwent decompression, thereby not capturing a proportion of patients who were not decompressed.

Two pertinent questions are always presented: what are the preferred options for relieving malignant ureteric obstruction? And what is the expected prognosis?5 In terms of methods of decompression, a previous comparative study discovered no relative superiority of retrograde stenting to percutaneous nephrostomy in the setting of infected obstructed uropathy caused by stones.76 Two recent review articles concluded that there were no data on the superiority of stent vs. percutaneous nephrostomy ± subsequent antegrade stent when considering malignant and benign ureteric obstruction.5,77

Clearly, the aim of relieving the obstruction depends on patient factors but would include improving renal function to enable further oncological treatment, to correct the symptoms of renal failure and to improve pain.7 This must be balanced against a patient’s expectation of quantity and quality of life. This is, of course, a challenging consultation, particularly in the acute setting when such patients often present.71 Despite extensive retrospective publications and several review articles, there is a paucity of data assessing the important issues of quality of life and prognostication in this cohort of patients.5

European Association of Urology guidelines on pain management recommend that for pelvic malignancies ‘it is good practice to drain symptomatic hydronephrosis at once, and to drain only one kidney (the less dilated and better appearing kidney or the one with the better function, if known) in asymptomatic patients’.14 They conclude that a nephrostomy tube is superior to a double-J stent for drainage for pelvic malignancies but advocate either stenting or nephrostomies in other tumour groups.14 Neither of these recommendations reference the literature nor do they mention implications of quality of life.

In the context of locally advanced non-metastatic bladder cancer with hydronephrosis, American Urological Association guidelines suggest placement of a ureteral stent.13

Complications

Another frequently neglected statistic for patients before them undergoing decompression is the proportion of time spent in hospital and the risk of complications. The proportion of patients who had complications was 41%, with 26% of patients never leaving hospital. Those who had an intervention spent 20% of their resultant lifetime in hospital. One paper stated that 69% of their patients never left hospital. Removing this apparent outlier from the pooled mean resulted in the figure of 17.8%.22 Despite improving renal function, creatinine did not return to baseline for patients, potentially avoiding an emergency situation but not reversing the damage caused by hydronephrosis.

Quality of life

Quality of life can be challenging to measure; early papers measured quality of life using the ‘useful life’ measure.50,67 Feng et al. and Hubner et al. reported greater proportions of patients achieving a good quality of life when compared with contemporary papers: 81–87% vs. 46%.20,21,50,62,67 While it is not entirely clear why there has been a reduction in patients experiencing ‘useful life’, it is possible that patient selection, subjective clinician perception of pain and possibly the increased use of opioid medication may have contributed.78,79 Furthermore, it is likely that the progression to use of patient-reported outcome measures rather than relying on clinicians’ opinions of what constitutes quality of life can explain in part the move from rudimentary to more patient-centred validated measures.

Three studies utilised patient-reported outcome measures demonstrating no statistically significant improvements in quality of life pre and post decompression.25,61,66 However, despite improvement in the use of patient-reported outcome measures, there were several limitations with the studies. Limitations of the Monskey et al. study included not measuring baseline symptoms and not having a control group.66 Lapitan et al., despite conducting a prospective study using functional assessment of cancer therapy – bladder, demonstrated lower scores pre and post decompression in comparison to other papers using functional assessment of cancer therapy – general.25 This is potentially related to the association between socioeconomic deprivation, educational attainment and scores in functional assessment of cancer therapy – general.80,81 A further limitation of the Lapitan et al. study, reducing its wider relevance, was the inclusion of patients solely with a diagnosis of cervical cancer.

Two papers looked at qualitative interviews. Qualitative analysis is helpful to develop themes. However, a small sample size, the challenges of confounders, single tumour group inclusion and the exclusion of patients without nephrostomies may limit its wider application.12,68

Prognostication

One group performed a prospective cohort study of patients with cervical cancer. Lapitan et al. followed up a cohort of patients who had malignant ureteric obstruction and assessed the outcomes of two groups: those who were decompressed and those who were not.25 At the outset, there appears to be a survival benefit with 38% vs. 28% survival at six months for those who underwent decompression vs. those who did not. By 12 months, however, both groups had the same survival of 16%.25

The most frequently found statistically significant indicators of poor prognosis among the literature were low serum albumin, no further treatment options, number of malignancy-related events (pleural effusion, metastatic disease, ascites), performance status of 2 or worse on the European Cooperative Cancer Group, the presence of metastatic disease and hyponatremia (Table 4). Two papers divided patients into groups depending on treatment options available; those with no treatment options had 0% 12-month survival and a median survival of 38 days. Combining these parameters with a larger patient group may help develop a prognostication tool for clinicians to aid decision-making (See Table 5).

Comparison of prognostication tools demonstrates that patients with none or one risk factor have more favourable outcomes with 12-month survival ranging from 20% to 78%28,42,71,72 and a median survival ranging between 9 and 13 months.30,36,38 In those patients with ‘intermediate’ risk factors (see Table 3), median survival ranged from 5.7 to 8.2 months.30,36,38 For those patients with two or more risk factors, median survival ranged from 1.7 to 2.6 months30,38 and 12-month survival ranged from 0% to 12%.9,28,42,71,72

Limitations

The reviewed data have significant heterogeneity, making conclusions regarding specific tumour types challenging. Sountoulides et al. comments on the ‘divergent nature of their group’. At one end of the spectrum, there are patients with very advanced disease who may not benefit from decompression; at the other are those who have further oncological and or surgical options who will naturally have a much longer life expectancy.5

There are only 25 papers published in the last 10 years; in this time, however, there have been significant advances in oncological treatment options. Therefore, outcomes may well be influenced by more conservative historic data.

Another limitation of this analysis is the retrospective nature of the data; there were only nine papers that were prospective in nature.9,10,25,31,43,48,54 Data on survival are lacking on those patients conservatively managed with only one paper including untreated patients in its survival data, which may lead to overstating median survival.25 There are clear worldwide variations in practice regarding discharge home. In one series, 69% of patients did not leave hospital after decompression;28 this contrasts with an average of 17% among other papers.

Limitations when reviewing prognostic tools include the fact that the majority of studies were retrospective in nature. The use of statistical analyses included univariate, paired-t as well as multivariate analysis, thus limiting transferability and utility on an individual patient basis.

Conclusion

In this post Montgomery era with the concept of the ‘reasonable patient’, can we continue to justify discussing decompression without stating to patients the evidence-based risks and benefits from the emergent body of literature?82 An overall complication risk of 41% and up to one-quarter of patients' remaining lifetime spent in hospital with a median survival of 6.4 months may encourage clinicians and patients to rethink the appropriateness of such interventions. We propose a contemporary multicentre prospective review of outcomes of this cohort of patients to enable evidence-based consultations for patients and their families. Further work in the domain of prognostication is needed to help best identify those patients who may benefit the most from decompression.

Declarations

Competing Interests

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Guarantor

JP.

Contributorship

JP and TA developed the idea for the article. JP, TA and OA undertook data collection. OA, TA, JP and AT undertook analysis of the data and interpretation. JP and TA drafted the article. OA and AT provided critical revision. JP, TA, OA and AT involved in final approval.

Provenance

Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Syed Shahzad.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the library staff at Ayr hospital for their help with sourcing papers for the review.

References (Refs. 31–82 are available in the online supplemental material)

- 1.Radecka E, Magnusson M, Magnusson A. Survival time and period of catheterization in patients treated with percutaneous nephrostomy for urinary obstruction due to malignancy. Acta Radiol 2006; 47: 328–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pradhan TS, Duan H, Katsoulakis E, Salame G, Lee Y-C, Abulafia O. Hydronephrosis as a prognostic indicator of survival in advanced cervix cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2011; 21: 1091–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Migita K, Watanabe A, Samma S, Ohyama T, Ishikawa H, Kagebayashi Y. Clinical outcome and management of ureteral obstruction secondary to gastric cancer. World J Surg 2011; 35: 1035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer JE, Yatsuhashi M, Green THJ. Palliative urinary diversion in patients with advanced pelvic malignancy. Cancer 1980; 45: 2698–2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sountoulides P, Pardalidis N, Sofikitis N. Endourologic management of malignant ureteral obstruction: indications, results, and quality-of-life issues. J Endourol 2010; 24: 129–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brin EN, Schiff MJ, Weiss RM. Palliative urinary diversion for pelvic malignancy. J Urol 1975; 113: 619–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyams ES, Shah O. Malignant extrinsic ureteral obstruction: a survey of urologists and medical oncologists regarding treatment patterns and preferences. Urology 2008; 72: 51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul AB, Love C, Chisholm GD. The management of bilateral ureteric obstruction and renal failure in advanced prostate cancer. Br J Urol 1994; 74: 642–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordeiro MD, Coelho RF, Chade DC, Pessoa RR, Chaib MS, Colombo-Junior JR, et al. A prognostic model for survival after palliative urinary diversion for malignant ureteric obstruction: a prospective study of 208 patients. BJU Int 2016; 117: 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishioka J, Kageyama Y, Inoue M, Higashi Y, Kihara K. Prognostic model for predicting survival after palliative urinary diversion for ureteral obstruction: analysis of 140 cases. J Urol 2008; 180: 618–621. discussion 621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dienstmann R, da Silva Pinto C, Pereira MT, Small IA, Ferreira CG. Palliative percutaneous nephrostomy in recurrent cervical cancer: a retrospective analysis of 50 consecutive cases. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008; 36: 185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bigum LH, Spielmann ME, Juhl G, Rasmussen A. A qualitative study exploring male cancer patients’ experiences with percutaneous nephrostomy. Scand J Urol 2015; 49: 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang S, Bochner B, Chou R, Dreocer R, Kamat A, Lerner S, et al. Treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: AUA/ASCO/ASTRO/SUO guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association: 9. See http://www.auanet.org/guidelines/muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer-new-(2017) (last checked 8 February 2018).

- 14.Paez Borda A, Charnay-Sonnek F, Fonteyne V and Papaioannou EG. Guidelines on pain management & palliative care. Arnhem: European Association of Urology: 12. See https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/25-Pain-Management_LR.pdf (2014, last checked 8 February 2018).

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management. London: NICE; 2015: 385. See https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng2/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-3744112 (last checked 8 February 2018). [PubMed]

- 16.Kamiyama Y, Matsuura S, Kato M, Abe Y, Takyu S, Yoshikawa K, et al. Stent failure in the management of malignant extrinsic ureteral obstruction: risk factors. Int J Urol 2011; 18: 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: W65–W94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d5928–d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emmert C, Rassler J, Kohler U. Survival and quality of life after percutaneous nephrostomy for malignant ureteric obstruction in patients with terminal cervical cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet 1997; 259: 147–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson JR, Urwin GH, Stower MJ. The role of percutaneous nephrostomy in malignant ureteric obstruction. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2005; 87: 21–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka T, Yanase M, Takatsuka K. Clinical course in patients with percutaneous nephrostomy for hydronephrosis associated with advanced cancer. Hinyokika Kiyo 2004; 50: 457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shekarriz B, Shekarriz H, Upadhyay J, Banerjee M, Becker H, Pontes JE, et al. Outcome of palliative urinary diversion in the treatment of advanced malignancies. Cancer 1999; 85: 998–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong IG, Han KS, Joung JY, Seo HK, Chung J. The outcome with ureteric stents for managing non-urological malignant ureteric obstruction. BJU Int 2007; 100: 1288–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapitan MCM, Buckley BS. Impact of palliative urinary diversion by percutaneous nephrostomy drainage and ureteral stenting among patients with advanced cervical cancer and obstructive uropathy: a prospective cohort. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2011; 37: 1061–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mann WJ, Hatch KD, Taylor PT, Partridge EM, Orr JW, Shingleton HM. The role of percutaneous nephrostomy in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol 1983; 16: 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudley BS, Gershenson DM, Kavanagh JJ, Copeland LJ, Carrasco CH, Rutledge FN. Percutaneous nephrostomy catheter use in gynecologic malignancy: M.D. Anderson Hospital experience. Gynecol Oncol 1986; 24: 273–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wong L-M, Cleeve LK, Milner AD, Pitman AG. Malignant ureteral obstruction: outcomes after intervention Have things changed? J Urol 2007; 178: 178–183. discussion 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tekin MI, Aytekin C, Aygun C, PeSkircioglu L, Boyvat F, Ozkardes H. Covered metallic ureteral stent in the management of malignant ureteral obstruction: preliminary results. Urology 2001; 58: 919–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azuma T, Nagase Y, Oshi M. Prognostic marker for patients with malignant ureter obstruction. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2013; 11: 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]