Abstract

Three phase 1 randomized single‐center studies assessed the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of vortioxetine after single‐ and multiple‐dose administration in healthy Japanese adults. Study 1 assessed the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine after administration of single rising doses to men and multiple doses to men and women; study 2 evaluated vortioxetine pharmacokinetics in elderly adults; and study 3 assessed food effects on vortioxetine pharmacokinetics in healthy men. The primary end points included pharmacokinetic parameters of vortioxetine and incidence of adverse events (AEs). Across all studies, 130 participants were randomized and 128 participants completed the studies. Vortioxetine was absorbed and eliminated from plasma slowly, and exposure to vortioxetine increased in an almost dose‐proportional manner. No clinically significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine or its metabolites were observed between the sexes in young and elderly adults. Study 3 demonstrated that vortioxetine and its metabolites had similar pharmacokinetics when administered in the fasted and fed states. Importantly, vortioxetine was safe and tolerated, with incidence of AEs comparable to that of placebo. No deaths or serious AEs leading to trial discontinuation were observed. Overall, vortioxetine pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability in Japanese adults were comparable to reports in non‐Japanese populations.

Keywords: vortioxetine, 5‐HT, antidepressant, multimodal treatment, major depressive disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a disabling condition that adversely affects patient quality of life, productivity, and overall health.1 Several classes of antidepressants are currently available for the management of MDD, including selective serotonin (5‐HT) reuptake inhibitors, 5‐HT and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, norepinephrine and specific serotonergic antidepressants.2 Although several antidepressants are available, many patients have inadequate response to treatment or experience intolerable adverse events (AEs).3, 4, 5 Therefore, the development of antidepressants with novel profiles would broaden the range of available options and optimize treatment for depression.

Vortioxetine is a multimodal antidepressant that has been developed for the treatment of MDD.6 Vortioxetine functions as a potent 5‐HT transporter inhibitor, 5‐HT1A receptor agonist, 5‐HT1B partial agonist, and antagonist at the 5‐HT3, 5‐HT1D, and 5‐HT7 receptors and exerts distinct effects across neural pathways associated with mood and cognition, including enhanced glutamate signaling.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 In vivo nonclinical studies have demonstrated that vortioxetine elevates the levels of several neurotransmitters (ie, 5‐HT, norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, acetylcholine, gamma‐aminobutyric acid, and glutamate) in the brain and exhibits antidepressive, antianxiety, and procognitive effects in animal behavioral models.6, 8, 9, 10, 11

Vortioxetine is extensively metabolized in the liver, primarily through oxidation and subsequent glucuronic acid conjugation, and cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) is the principal CYP isoform mediating clearance of vortioxetine.12, 13 The major metabolite of vortioxetine is the carboxylic acid metabolite Lu AA34443, which is pharmacologically inactive.13 No inhibitory or inducing effect of vortioxetine was observed in vitro for CYP isozymes CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4/5.7

The clinical pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of vortioxetine have been investigated in phase 1 trials conducted in the United States and Europe.14, 15, 16 Vortioxetine absorption and exposure increased in a dose‐proportional manner after administration as a single dose (10–75 mg) or multiple doses (2.5–60 mg/day) to young adults. Clinical studies of vortioxetine in the elderly population revealed similar pharmacokinetics in elderly adults versus young adults and comparable safety and tolerability profiles.17 In subsequent phase 2 and 3 clinical trials conducted in the United States and Europe, vortioxetine exhibited antidepressant efficacy and improvements in cognitive function at doses of 10 to 20 mg/day in younger MDD patients and at the 5‐mg dose in elderly patients.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Because variations have been observed in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antidepressants across different races and ethnicities due to genetic polymorphisms (eg, in CYP2D6), it is important that the clinical pharmacology of vortioxetine be evaluated in diverse populations.23, 24, 25

To date, the pharmacokinetics and safety profiles of vortioxetine have not been reported in Japanese populations. Here, we describe the findings from 3 phase 1 trials conducted in Japanese adults that investigated the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of vortioxetine in young adults following single rising or multiple doses (study 1), the pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of vortioxetine in the elderly population (study 2), and the effects of food on vortioxetine pharmacokinetics (study 3).

Methods

Three phase 1 randomized single‐center studies were conducted in healthy Japanese adults (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). Study protocols were reviewed and approved by the following institutional review boards: Tokyo Heart Center, Osaki Hospital (study 1); Medical Co. LTA Kyushu Clinical Pharmacology Research Clinic (study 2); and Medical Co. Houei‐kai Sekino Clinical Pharmacology Clinic (study 3). Study 1 was conducted at Tokyo Heart Center, Osaki Hospital, Japan; study 2 at Medical Co. LTA Kyushu Clinical Pharmacology Research Clinic, Japan; and study 3 at Sekino Hospital, Japan. All study protocols were conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice (GCP), International Conference for Harmonisation, Harmonised Tripartite Guideline E6 for GCP, and all applicable laws and regulations. Enrolled participants for each study provided written informed consent before undergoing any study procedures.

Table 1.

Summary of Study Designs Across the 3 Trials

| Study | Objective | Population | Study Design | Treatment Cohorts | Administration Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | Assess PK of VOR after administration of single rising doses | 45 healthy adult men | Phase 1 single‐dose, PBO‐controlled DB study | 2.5 mg VOR (n = 6) or PBO (n = 3) fasted, then 2.5 mg fed on day 15a 5 mg VOR (n = 6) or PBO (n = 3) 10 mg VOR (n = 6) or PBO (n = 3) 20 mg VOR (n = 6) or PBO (n = 3) 40 mg VOR (n = 6) or PBO (n = 3) | Study drug administration: days 1 and 15 (2.5‐mg cohort only) Discharge: days 7 and 21 (2.5‐mg cohort only) Poststudy exam: days 10 and 24 (2.5‐mg cohort only) |

| 1B | Characterize PK of VOR after administration of multiple doses | 45 healthy adult men and women | Phase 1 multiple‐dose, PBO‐controlled DB study | 5 mg VOR (n = 6 male; n = 6 female) or PBO (n = 3 male; n = 3 female) 10 mg VOR (n = 6 male; n = 6 female) or placebo (n = 3 male; n = 3 female) 20 mg VOR (n = 6 male) or PBO (n = 3 male) | Study drug administration: days 1 to 12 Discharge: day 17 Poststudy exam: day 20 |

| 2 | Characterize PK of VOR in elderly adults | 20 elderly adult men and women | Phase 1 single‐dose, PBO‐controlled DB study | 10 mg VOR (n = 8) or PBO (n = 2) in elderly men, fasted 10 mg VOR (n = 8) or PBO (n = 2) in elderly women, fasted | Study drug administration: day 1 Discharge: day 6 |

| 3 | Characterize PK of VOR in fed and fasted states | 20 healthy adult men | Phase 1 single‐dose, 2‐period crossover OL study | 10 mg VOR in the fasted state followed by 10 mg VOR in the fed state 10 mg VOR in the fed state followed by 10 mg VOR in the fasted state | Period 1: Study drug administration: day 1 Discharge: day 8 Admission to period 2: day 14 Period 2: Study drug administration: day 15 Discharge: day 22 |

DB, double‐blind; OL, open label; PBO, placebo; PK, pharmacokinetics; VOR, vortioxetine.

The 2.5‐mg cohort was the only one to receive VOR under both fasted and fed conditions; all other treatment cohorts in study 1A received treatment under fasted conditions.

Study Participants

For each study, participants were screened for enrollment from 28 to 2 days before treatment. Participants who met the inclusion criteria for each study were eligible for trial participation: men (all studies) and women (studies 1 and 2); aged between 20 and 45 years, inclusive (studies 1 and 3), or between 65 and 85 years (study 2); body weight ≥ 50 kg for men (all studies) and ≥ 45 kg for women (studies 1 and 2); and body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2, inclusive (studies 1 and 3), or ≥ 17.6 but < 26.4 kg/m2, inclusive (study 2). Participants were ineligible if they met any of the following exclusion criteria: received any investigational drug within 16 weeks (studies 1 and 2) or 90 days (study 3) before screening, any medication within 28 days before the first dose of study drug, or vortioxetine in a previous clinical study; had clinically significant comorbidities that might complicate treatment or potentially confound the study results; had known hypersensitivity or allergies to medications, poor peripheral venous access, or had undergone whole‐blood collection before the start of study drug administration; had positive test results for hepatitis or human immunodeficiency virus, positive urine drug test result at screening, history of drug/alcohol abuse within 2 years before screening, or history of cancer; had clinically significant vital sign or electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormality at screening or on day ‐1; if female, was pregnant or lactating (study 1, part B only); if female, was premenopausal (study 2 only); and had consumed food or beverages containing grapefruit, caffeine, or alcohol within 72 hours before the first dose.

Study Design

Study 1A (Single‐Rising‐Dose Study)

In this randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study, vortioxetine or placebo was administered as a single oral dose in an ascending manner (Table 1). Forty‐five healthy men were randomized equally into 5 dose cohorts to receive a single dose of vortioxetine or placebo (2:1; Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). The initial dose was 2.5 mg, and the dose was escalated by doubling the dose up to the maximal dose of 40 mg in 5 steps. Dose escalation was determined by the investigator in consultation with the on‐site medical expert on evaluation of the safety and pharmacokinetic data collected from participants on day 5 and 48 hours postdose, respectively. Participants were admitted to the site and received vortioxetine or placebo on day 1 with 250 mL of water after ≥ 10 hours of fasting; they were then discharged from the site on day 7 and returned to the site on day 10 for poststudy exams. The 5‐, 10‐, 20‐, and 40‐mg doses were administered in the fasted state only. Participants randomized to the 2.5‐mg dose received vortioxetine in the fasted state on day 1 and then received the same dose in the fed state (30 minutes after breakfast) on day 15 after a 14‐day washout period; participants were confined to the site until day 21 and visited the site again on day 24 for poststudy exams.

Study 1B (Multiple‐Rising‐Dose Study)

In this randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study, vortioxetine or placebo was administered as multiple doses over a 12‐day period (Table 1). Twenty‐seven healthy men were randomized equally into 3 dose cohorts to receive multiple doses of 5, 10, or 20 mg vortioxetine or placebo (2:1 per cohort; Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). Dose escalation was decided in same manner as in study 1A. Subsequently, 18 healthy women were randomized equally into 2 dose cohorts to receive multiple doses of 5 or 10 mg vortioxetine or placebo (2:1 per cohort). Because of tolerability issues previously reported in women treated with higher doses of vortioxetine,14, 15, 26 female participants in this study were administered doses after the tolerability of each dose was assessed in men. Across all dose groups, participants were administered treatment daily in the fed state from days 1 to 12 and then discharged from the site on day 17; participants returned to the study site on day 20 for poststudy exams.

Study 2 (Elderly Population)

This was a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind study conducted in elderly adults (aged 65 to 85 years). Twenty elderly men and women (10 each) were randomized on day ‐1 (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S1) and received a single oral dose of 10 mg vortioxetine or placebo (4:1 per cohort) on day 1 under fasting conditions in the morning. Participants were observed on‐site from day 1 to day 5, during which study exams were conducted, and were then discharged on day 6 after the end‐of‐study assessment.

Study 3 (Food Effects)

In this open‐label crossover study, 20 healthy male adults were randomized 1:1 to 2 treatment sequences (A and B), each of which consisted of 2 treatment periods (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure S1). In treatment sequence A, a single oral dose of vortioxetine was first administered under fasted conditions and then again under fed conditions, whereas in treatment sequence B the reverse occurred: a single oral dose of vortioxetine was first administered in the fed state and then again in the fasted state. For administration in the fasted state, participants received 10 mg of vortioxetine with water after ≥ 10 hours of fasting; in the fed state, participants consumed a high‐fat breakfast (≥ 900 kcal containing ≥ 35% of calories from fat) within a 20‐minute period and were administered 10 mg vortioxetine with water within 10 minutes of having finished breakfast. During both periods, participants visited the study site before treatment (day ‐1 and day 14) and were confined to the site for 8 nights after having received a single dose of 10 mg vortioxetine on day 1 and day 15.

Pharmacokinetic Evaluation

Pharmacokinetic parameters and urinary excretion ratios of vortioxetine and its metabolites were evaluated in all studies. Blood samples for the determination of plasma concentrations of vortioxetine and its metabolites Lu AA34443 (metabolite 1) and Lu AA39835 (metabolite 2) in these studies were collected in Vacutainers containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Plasma and urine samples were stored at ‐20°C or lower prior to the analysis. A liquid–liquid extraction method was used for sample preparation. This was followed by separation of the analytes by high‐performance liquid chromatography on a CAPCELL P AK SCX UG80 column (Shiseido). The mobile phase consisted of 10 mmol/L ammonium formate/formic acid (400:1) and acetonitrile (20:80). Eluting compounds were detected by tandem mass spectrometry in the positive ion mode. The extracted ions monitored for vortioxetine, metabolite 1, and metabolite 2 were m/z 299 → 150, m/z 329 → 286, and m/z 315 → 166; internal standards used were Lu AA37038, Lu AA37208, and Lu AE68011. The linear ranges for the plasma assay were 0.08 to 80 ng/mL for vortioxetine, 0.2 to 200 ng/mL for metabolite 1, and 0.04 to 40 ng/mL for metabolite 2; calibration ranges for the urine assay were 8 to 2000 ng/mL for vortioxetine, 20 to 5000 ng/mL for metabolite 1, and 8 to 2000 ng/mL for metabolite 2. The accuracy and precision for these analytes were within 89.2% to 112.0% and 3.0% to 7.4%, respectively. For all assays, the lower limit of quantification was the lower end of the linear ranges. For all studies, 2 mL of whole blood was collected after study drug administration on day 1 for CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 genotyping, which was performed using the Amplichip P450 Test (Mitsubishi Chemical Medience Corporation).

Plasma and urinary concentrations of vortioxetine and its metabolites were measured by high‐performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry at JCL Bioassay (Nishiwaki, Japan). Blood was collected at predefined times for each study. In study 1A, blood samples were collected on day 1 predose, and 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 16 hours postdose, and 24 (day 2), 36 (day 2), 48 (day 3), 72 (day 4), 96 (day 5), 120 (day 6), 144 (day 7), and 216 (day 10) hours postdose. In study 1B, samples were collected on day 1 predose and 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 16 hours postdose; on day 2 to day 11 predose; on day 12 predose and 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 16 hours postdose; and 24, 36 (day 13), 48 (day 14), 72 (day 15), 96 (day 16), 120 (day 17), and 192 (day 20) hours post–last dose. In study 2, samples were collected on day 1 predose and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 16 hours postdose and 24 (day 2), 36 (day 2), 48 (day 3), 72 (day 4), 96 (day 5), and 120 (day 6) hours postdose. In study 3, samples were collected on day 1 predose and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 16 hours postdose and 24 (day 2), 36 (day 2), 48 (day 3), 72 (day 4), 96 (day 5), 120 (day 6), 144 (day 7), and 168 (day 8) hours postdose.

Urine was collected at predefined times for each study. In study 1A, samples were collected on day 1 predose (spot urine collection) and in pooling intervals of 0 to 6 (day 1), 6 to 12 (day 1), 12 to 24 (day 2), and 24 to 48 (day 3) hours postdose. In study 1B, samples were collected from participants in the 5‐mg cohort at predose on days 1 to 16 and then in 24‐hour intervals. In the 10‐ and 20‐mg cohorts, urine was collected on day 12 at 0 to 24 hours postdose. In study 2, urine was collected on day 1 predose and pooled in 0 to 24 (day 2), 24 to 48 (day 3), 48 to 72 (day 4), 72 to 96 (day 5), and 96 to 120 (day 6) hours postdose. In study 3, samples were collected on day 1 predose and pooled in 0 to 6 (day 1), 6 to 12 (day 1), 12 to 24 (day 2), 24 to 48 (day 3), 48 to 72 (day 4), 72 to 96 (day 5), 96 to 120 (day 6), 120 to 144 (day 7), and 144 to 168 (day 8) hours postdose.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated with standard noncompartmental analysis using WinNonlin software (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, California). Metabolic ratios were calculated based on systemic drug exposure (described by the area under the plasma concentration–time curve [AUC]) of vortioxetine and its metabolites. Cumulative urinary excretion ratios (% of dose as unchanged compound) were calculated for vortioxetine, its metabolites, and the total compound. For all participants who received vortioxetine, summary statistics of plasma concentrations of unchanged vortioxetine and its metabolites were determined for each time, and plasma concentration–time curves (mean with standard deviation [SD]) were generated.

In study 1B and study 3, pharmacokinetic parameters were compared between groups (male vs female and fasted vs fed, respectively) using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) model: AUC and maximum observed plasma concentration (Cmax) values were log‐transformed before analysis; least‐squares (LS) mean, point estimate, and confidence interval (CI) values (95%, study 1B; 90%, study 3) were calculated using back‐transformed values from the difference calculated on the log scale; and analysis of time to reach Cmax (Tmax) values was performed using Wilcoxon's signed rank test.

Safety Evaluation

For all studies, AEs, body weight, vital signs, 12‐lead ECG results, and clinical laboratory results (hematology, serum chemistry, blood coagulation, and urinalysis) were recorded during all stages. Treatment‐emergent AEs (TEAEs) were defined as events that occurred or existed and worsened after study drug administration and were assessed for each dose group (2.5–40 mg), dosing condition (fasted and fed), and sex (male and female). The overall incidence, intensity, and relationship to the study drug were calculated for each TEAE across all treatment groups and compared with those of the placebo.

Results

Study Participants

Across all studies, 130 participants were randomized, and 128 participants completed the studies (Table 1, Supplemental Figure S1). In studies 1 and 2, all 90 and 20 participants, respectively, who were randomized completed the studies. In study 3, 18 of 20 participants completed the study; 1 participant withdrew because of an AE (vomiting), and another withdrew for personal reasons after completion of period 1. Most participants were classified as extensive CYP2D6 metabolizers (data not shown); no CYP2D6 poor metabolizers (PMs) were included in these studies.

Overall, no significant differences in age, height, body weight, BMI, or creatinine clearance (CLcr) at baseline were observed among treatment groups in any study. In study 1, all baseline characteristics were comparable between dose groups except for body weight in women (part B), which was slightly higher in the 5‐mg dose cohort than in the placebo or 10‐mg dose groups. In study 2, all characteristics were comparable across treatment groups for both sexes except for CLcr, which displayed high interparticipant variability, and mean weight and height, which were higher in elderly men than in women. In study 3, no significant differences in baseline characteristics were observed in participants randomized to treatment sequences A and B.

Pharmacokinetics of Vortioxetine Following Single or Multiple Doses (Studies 1A and 1B)

Pharmacokinetic parameter estimates in single‐ and multiple‐dose studies were summarized for each treatment regimen (Tables 2 and 3). Following single or multiple oral doses, vortioxetine was absorbed slowly, with the median time to reach Tmax 6 to 13 hours (Tables 2 and 3). Elimination of vortioxetine from the plasma was also slow, as the mean terminal elimination half‐life (T1/2) ranged from 50 to 70 hours in the single‐rising‐dose study (Table 2, Supplemental Figure S2A) and from 34 to 113 hours in the multiple‐dose study (Table 3, Supplemental Figure S2B).

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Vortioxetine Following Single‐Dose Administration to Men (Study 1A)

| 2.5 mg | 5 mg | 10 mg | 20 mg | 40 mg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, Arithmetic Mean (SD) | (n = 5) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 4) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.8 (0.3) | 1.9 (0.1) | 3.5 (0.8) | 7.7 (1.7) | 19.4 (2.4) |

| Tmax (h) | 10.0 (2.8) | 10.0 (2.34) | 10.0 (2.5) | 9.0 (3.3) | 6.3 (1.3) |

| AUC0–inf (ng·h/mL) | 56.5 (20.7) | 188.1 (68.3) | 348.1 (153.5) | 560.2 (228.4) | 1308 (475.5) |

| T1/2 (h) | 48.9 (7.2) | 69.4 (20.8) | 66.0 (20.0) | 55.1 (16.0) | 56.6 (14.0) |

| CL/F (L/h) | 50 (20) | 29.6 (10.3) | 35.2 (19.2) | 41.4 (17.6) | 34.0 (13.1) |

| Fe0–48 (%)a | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.007 (0.018) | 0.023 (0.023) | 0.034 (0.017) |

AUC0–inf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity; CL/F, apparent clearance after extravascular administration; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; Fe0–48, fraction excreted from 0 to 48 hours; SD, standard deviation; T1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; Tmax, time to reach Cmax.

Cumulative excretion ratios (% of dose) of vortioxetine are reported.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Vortioxetine Following Multiple‐Dose Administration (Study 1B)

| Day 1a | Day 12b | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||||||

| 5 mg | 10 mg | 20 mg | 5 mg | 10 mg | 5 mg | 10 mg | 20 mg | 5 mg | 10 mg | ||

| Characteristic, Arithmetic Mean (SD) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 5) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 5) | (n = 6) | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 1.8 (0.2) | 4.3 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.5) | 2.7 (0.4) | 3.4 (1.4) | 8.0 (2.6) | 21.2 (4.1) | 21.4 (7.7) | 13.5 (4.4) | 13.8 (7.7) | |

| Tmax (h) | 11.8 (2.9) | 12.7 (5.9) | 9.0 (1.8) | 10.2 (2.5) | 12.7 (6.6) | 8.3 (1.9) | 8.3 (2.1) | 8.0 (1.3) | 6.4 (3.1) | 7.7 (0.5) | |

| AUC0–24 (ng·h/mL) | 31.6 (5.0) | 71.0 (19.9) | 109.8 (23.0) | 47.1 (6.6) | 53.3 (22.9) | 162.9 (47.5) | 431.7 (76.0) | 432.6 (170.6) | 284.5 (102.5) | 294.8 (166.0) | |

| T1/2 (h) | 68.0 (25.8) | 66.4 (38.3) | 44.0 (9.7) | 113.2 (108.7) | 34.2 (24.3) | 58.0 (15.2) | 65.1 (13.3) | 56.8 (17.0) | 79.8 (26.9) | 58.0 (23.3) | |

| CL/F (L/h) | 30.6 (9.4) | 29.1 (12.0) | 50.4 (17.1) | 22.3 (19.6) | 99.3 (104.7) | 33.1 (10.3) | 23.8 (4.4) | 51.5 (16.6) | 20.2 (9.5) | 69.9 (94.8) | |

| Fe0–x (%) | VOR | 0.00 (0.0) | N/A | N/A | 0.00 (0.0) | N/A | 0.0072 (0.018) | N/A | N/A | 0.0494 (0.087) | N/A |

| M1 | 0.636 (0.215) | N/A | N/A | 0.532 (0.095) | N/A | 16.92 (3.44) | N/A | N/A | 14.34 (2.86) | N/A | |

| CLr (L/h)c | 7.68 (1.68) | 4.20 (0.56) | 8.27 (1.35) | 6.58 (0.97) | 8.52 (2.87) | 6.43 (1.56) | 4.43 (0.84) | 10.75 (0.90) | 5.46 (0.81) | 7.75 (1.06) | |

| R(AUC) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5.2 (1.4) | 6.2 (0.9) | 3.9 (1.0) | 6.0 (2.0) | 5.3 (2.2) | |

| R(Cmax) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4.4 (1.1) | 5.1 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.7) | 5.0 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.5) | |

AUC0–24, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to 24; CL/F, apparent clearance after extravascular administration; CLr, renal clearance; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; Fe0–x, fraction excreted from 0 to a defined time point; M1, metabolite 1; N/A, not applicable; R(AUC), cumulative ratio of AUC values; R(Cmax), cumulative ratio of Cmax values; SD, standard deviation; T1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; Tmax, time to reach Cmax; VOR, vortioxetine.

Fe0–x (%) values for vortioxetine are reported from 0 to 24 hours (day 1).

Fe0–x (%) values for vortioxetine are reported from 0 to 288 hours (day 12).

CLr values are reported for metabolite 1; vortioxetine and metabolite 2 were undetectable.

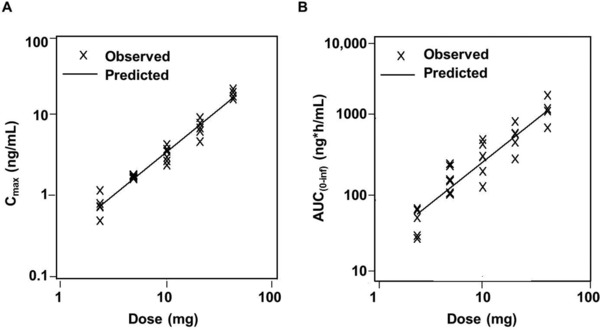

Following single oral doses (study 1A), exposure to vortioxetine based on AUC and Cmax values appeared to increase in an almost dose‐proportional manner at a dose range between 2.5 and 40 mg (Figure 1). Based on analysis of the dose–AUC relationship using a power model, the slope of AUC0–inf was 1.053, and the 95%CI included 1 (95%CI, 0.867–1.238), whereas the 95%CI of the slope for Cmax did not include 1 (95%CI, 1.016–1.197); however, the point estimate was close to 1 (1.107).

Figure 1.

Dose–exposure relationship of vortioxetine (study 1A). Analysis of vortioxetine (A) Cmax and (B) AUC0–inf exposure by dose using a power model (Y = α × DOSEβ). In this model, the exponent (β) is the slope and measure of dose proportionality, which is achieved when β = 1. AUC0–inf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration.

In the multiple‐dose study (study 1B), plasma concentrations of vortioxetine gradually increased with repeated doses (Table 3), reaching steady state by approximately 12 days for the 5‐ and 20‐mg doses in men and the 10‐mg dose in women. However, trough plasma concentrations for the 10‐mg dose in men and the 5‐mg dose in women did not reach steady state even after 12 days (Supplemental Figure S2B). For all dose groups, the total clearance of vortioxetine did not significantly differ between day 1 and day 12, but it was relatively higher in women taking 10 mg vortioxetine. Following multiple oral doses, Cmax and AUC values were 3‐ to 5‐fold and 4‐ to 6‐fold higher, respectively, on day 12 than after a single dose (Table 3). In men, a dose‐dependent increase in exposure was observed on day 1; however, exposure on day 12 was similar between the 10‐ and 20‐mg doses because plasma concentrations of vortioxetine did not attain steady state by day 12 in the 10‐mg dose group (Table 3). In women, exposure to vortioxetine was similar between the 5‐ and 10‐mg doses on day 12. It should be noted that 1 woman in the 10‐mg dose group exhibited extremely low plasma concentrations and a higher rate of clearance (263 L/h) than the mean (20 to 52 L/h).

To determine whether exposure to vortioxetine differed between the sexes, an ANOVA was applied for the log‐transformed and body‐weight‐adjusted Cmax and AUC values for day 12. At the 5‐mg dose, the point estimates for the difference in exposure between women and men were 1.776 (95%CI, 1.087–2.902) and 1.754 (95%CI, 1.100–2.796) for AUC and Cmax values, respectively, suggesting higher exposure in women. However, the opposite effect was observed at the 10‐mg dose, with point estimates of 0.465 (95%CI, 0.201–1.075) and 0.463 (95%CI, 0.219–0.978) suggesting higher exposure in men. Because of these inconsistent results and the limited number of participants, it was inconclusive whether exposure to vortioxetine differed between the sexes.

Pharmacokinetic analyses detected 2 metabolites of vortioxetine: metabolite 1 (Lu AA34443) and metabolite 2 (Lu AA39835). Metabolite 1 was the major byproduct of vortioxetine, present at high levels in the plasma and urine in the single‐dose study (Table 2, Supplemental Table S1) and multiple‐dose study (Table 3). Elimination of metabolite 1 from the plasma was slow, as mean T1/2 values ranged from 50.61 to 81.23 hours, whereas plasma concentrations of metabolite 2 were low among the dose groups throughout the dosing period. After a single dose, the median Tmax of metabolite 1 fell between 4.5 and 6 hours (Supplemental Table S1), which is smaller than what was observed for vortioxetine, indicating presystematic metabolism of the parent drug. Further, systemic exposure was nearly comparable to that of vortioxetine (metabolic ratios between 1.06 and 1.56), and no significant differences were observed among the dose groups.

Vortioxetine and its metabolites were all detected in the urine, but metabolite 1 accounted for the majority, and urinary excretion of vortioxetine and metabolite 2 were inappreciable (Table 3). Only renal clearance (CLr) of metabolite 1 was estimated to be between 3.102 and 4.217 L/h following a single dose of vortioxetine (Supplemental Table S1) and between 4.2 and 10.8 L/h following multiple doses (Table 3).

Pharmacokinetics of Vortioxetine in Elderly Adults (Study 2)

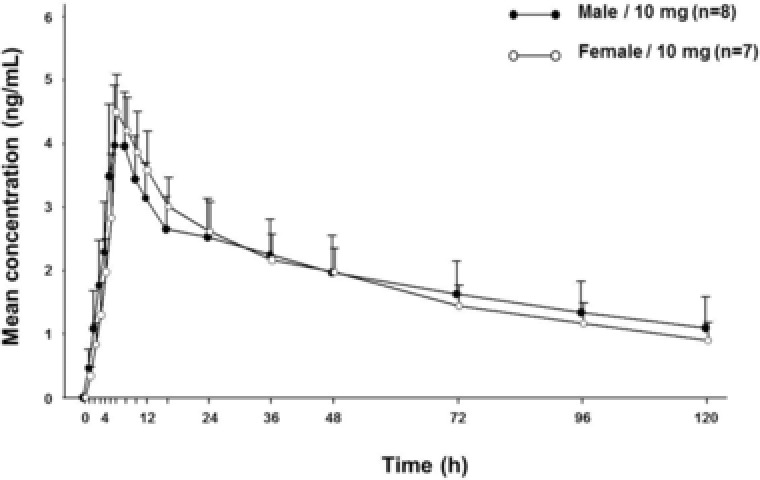

To evaluate the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine in elderly Japanese adults, plasma concentration–time curves and urinary excretion ratios for vortioxetine and its metabolites were calculated after single‐dose administration of 10 mg. As in the younger population, vortioxetine plasma concentrations and exposures were similar in elderly men and women (Figure 2, Table 4, and Supplemental Figure S2C). Vortioxetine was slowly absorbed and eliminated in elderly men and women; the median Tmax was 6 hours for both groups, and the T1/2 was 85 and 64 hours in elderly men and women, respectively.

Figure 2.

Vortioxetine concentration–time profiles in the elderly population. Mean plasma concentrations of vortioxetine after administration of a single 10‐mg dose to elderly men and women. One woman was excluded from the pharmacokinetic analysis set because she experienced an AE (vomiting) after study drug administration. Values represent arithmetic mean; concentrations below the limit of quantification were entered as zero and included as such in the calculation of means. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. AE, adverse event.

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Vortioxetine in the Elderly Population (Study 2)

| Administration of Single 10‐mg Dose | ||

|---|---|---|

| Elderly Men | Elderly Womenb | |

| Characteristic, Arithmetic Mean (SD)a | (n = 8) | (n = 7) |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.6) |

| Tmax (h) | 6.0 (5‐8) | 6.0 (6‐10) |

| AUC0–inf (ng·h/mL) | 378.0 (170.0) | 305.0 (80.2) |

| T1/2 (h) | 85.2 (29.8) | 63.5 (10.7) |

| Fe0–120 (%) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) |

AE, adverse event; AUC0–inf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; Fe0–120, fraction excreted from 0 to 120 hours; SD, standard deviation; T1/2, terminal elimination half‐life; Tmax, time to reach Cmax.

Tmax is presented as median (min‐max).

One woman was excluded from the pharmacokinetic analysis set because she experienced an AE (vomiting) after study drug administration.

Metabolite 1 exhibited similar absorption times in elderly men (median Tmax, 7 hours) and women (median Tmax, 5 hours). Although the Cmax values of metabolite 1 were >2‐fold higher than those of vortioxetine, the metabolic ratio of metabolite 1 relative to vortioxetine was 1.3 in both elderly men and women (Supplemental Table S2). Mean T1/2 values for metabolite 1 were 93.6 and 71.5 hours in elderly men and women, respectively (Supplemental Table S2). Compared with vortioxetine and metabolite 1, metabolite 2 had very low plasma concentrations in elderly men and women (Table 4, Supplemental Table S2). The only compound detected in the urine over the 120 hours postdose was metabolite 1 (Supplemental Table S2).

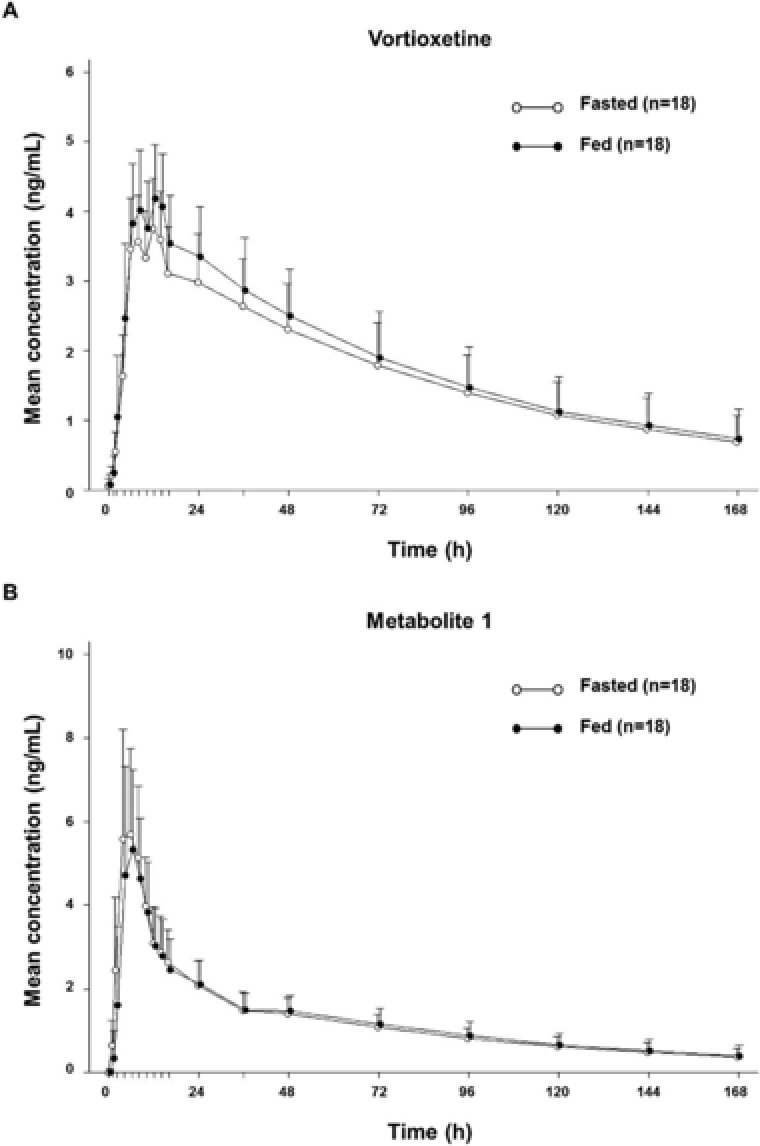

Effects of Food on Vortioxetine Pharmacokinetics (Study 3)

To assess the effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine, pharmacokinetic parameters were compared between fasted and fed states after administration of a single 10‐mg dose to healthy men in a crossover study (Figure 3A, Supplemental Table S3). Regardless of food intake, vortioxetine was slowly absorbed (median Tmax, 12 hours) and eliminated (mean T1/2, 68 hours); no statistical differences were observed. The 90%CIs for the LS mean ratios of the Cmax and the AUC were within the no‐effect boundary (90%CI, 0.8–1.25) for each parameter.

Figure 3.

Vortioxetine concentration–time profiles in the fed and fasted states (study 3). Mean plasma concentration–time profiles of vortioxetine (A) and metabolite 1 (B) after single‐dose administration of 10 mg to healthy men in the fasted and fed states. Values represent arithmetic mean; concentrations below the limit of quantification were entered as zero and included as such in the calculation of means. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean.

We also evaluated the effect of food on the pharmacokinetic properties of metabolite 1 and found no statistically significant differences. The median Tmax was 6 hours under both fasted and fed conditions, and the metabolic ratios of metabolite 1 to vortioxetine were comparable in the fasted (0.716) and fed (0.653) states (Figure 3B). Similar to what was observed in study 1 and study 2, metabolite 1 was the only compound detected in urine, and cumulative urinary excretion ratios over the 168 hours postdose were similar in the fasted (15.164%) and fed (15.534%) states.

Safety and Tolerability

Across all studies, the incidence of AEs was comparable in the vortioxetine and placebo groups. Importantly, no deaths or serious AEs leading to trial discontinuation were observed for any of the studies.

After administration of single doses (study 1A), vortioxetine was tolerated up to 20 mg in healthy men (Supplemental Table S4). No AEs were observed in the lower‐dose groups (2.5, 5, and 10 mg), and only 1 man exhibited abnormal blood creatine phosphokinase levels at the 20‐mg dose. Seven AEs were reported in the single 40‐mg dose group, including observation of a relatively high incidence of gastrointestinal AEs (ie, diarrhea and vomiting).

After administration of multiple doses (study 1B), vortioxetine was tolerated up to 20 and 10 mg in healthy men and women, respectively (Supplemental Table S5). The overall incidence of TEAEs ranged from 16.7% (1 participant) to 33.3% (2 participants) in men and from 50.0% (3 participants) to 66.7% (4 participants) in women; however, all TEAEs were mild in intensity. The most common AEs with a causal relationship to vortioxetine were determined by incidence and intensity across doses, compared with those of placebo, and included diarrhea, nausea, and headache. No clinically significant differences were observed in vortioxetine tolerability between men and women at doses of 10 mg and lower. Further, no dose‐dependent effects were observed on the overall severity or incidence of TEAEs.

Vortioxetine was also safe and tolerated in the elderly population after a single dose of 10 mg vortioxetine (Supplemental Table S6). Across the 20 participants, 2 elderly men and 2 elderly women experienced 1 or more AEs, all of which were mild in intensity. A skin and subcutaneous tissue disorder (acne) was reported in 2 elderly men, one of whom received placebo, whereas the other received vortioxetine. Two elderly women who received vortioxetine reported AEs of gastrointestinal disorders (diarrhea and vomiting) and abnormal laboratory investigations (urine β2‐microglobulin increased). TEAEs were not reported in elderly women who received placebo.

In the food‐effects study, no significant differences in safety profiles were observed under fasted and fed conditions. The AEs with a causal relationship to vortioxetine were vomiting, dysphoria, and increased blood creatine phosphokinase levels (Supplemental Table S7).

Discussion

The studies described here were the first to assess the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of vortioxetine in healthy Japanese adults. Consistent with the findings reported in non‐Japanese populations, vortioxetine was absorbed and eliminated slowly; however, our study revealed a few minor differences in vortioxetine pharmacokinetic parameters that are discussed below.14

Dose‐proportional increases in vortioxetine exposure have been previously reported in non‐Japanese studies, which tested a broader range of doses (10–75 mg) than what was evaluated in our study (2.5–40 mg).14 In this study, vortioxetine exposure in healthy Japanese adults appeared to increase in a dose‐proportional manner, as measured by the dose–AUC relationship; however, the 95%CI of the slope for the dose–Cmax relationship slightly exceeded 1 in the Japanese population. Considering that the average time to reach steady state would be 14 days given a median half‐life of 67 hours for vortioxetine, the 12‐day multiple‐dosing period in this study was not sufficiently long enough to achieve complete steady state. Comparing the values of vortioxetine exposure between the 2 populations revealed that exposure was slightly elevated in Japanese adults versus non‐Japanese adults, although the magnitude of the difference was not significant. It should be noted that there were considerable differences in body weight among participants; in the non‐Japanese population, the range was between 45 and 105 kg, whereas in the Japanese study, body weight ranged from 51 to 79 kg.14 Considering that no significant effect of body weight on vortioxetine pharmacokinetics was detected in a population meta‐analysis,27 this finding was not considered clinically significant enough to warrant dose adjustments.

In non‐Japanese populations, no clinically meaningful differences were observed in vortioxetine pharmacokinetics between the sexes.14 In the Japanese population, slight differences were observed between men and women for exposure, plasma concentration, and clearance of vortioxetine. However, these effects were not consistently observed, and given the large intersubject variability and small sample size within each group, the findings were inconclusive. Although further investigation would be required to determine whether the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine are affected by sex in the Japanese population, findings from studies conducted across different geographical populations support the conclusion that no dose adjustment is warranted for vortioxetine based on sex.

Because depression is highly prevalent in the elderly population, and age‐related changes in antidepressant pharmacokinetics have been reported to increase the risk for clinically significant AEs,17, 28, 29, 30 we evaluated the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine in elderly adults. Consistent with what has been observed in non‐Japanese populations, no major differences in vortioxetine pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability between elderly men and women were observed. Although the studies reported here were not designed to test the effects of age, cross‐trial comparisons between study 1 (young adults) and study 2 (elderly adults) demonstrated that at the 10‐mg dose, vortioxetine exposure was slightly higher in elderly than in younger adults. The magnitude of the difference was not considered clinically significant; however, the observation of elevated exposure in elderly adults is consistent with what has been reported for vortioxetine in other studies.15, 26 Although data for vortioxetine in the elderly population are limited, findings from US‐based clinical trials support the conclusion that the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine were generally similar in the 2 age groups and that no dose adjustment is necessary based on age. Our findings demonstrated at the very least that vortioxetine was safe and tolerated at the 10‐mg dose in elderly men and women.

Vortioxetine is primarily metabolized by CYP2D6, which is also responsible for the metabolism of a broad variety of drugs.25 Genetic polymorphisms in CYP2D6 have been reported to affect the rate of drug elimination and metabolism and contribute to interindividual variability in tolerability to antidepressants.23, 24, 25 Based on the level of metabolic activity, individuals are phenotypically classified as extensive metabolizers (EMs), intermediate metabolizers (IMs), PMs, or ultrarapid metabolizers of drugs metabolized by this enzyme.31 However, the prevalence of these phenotypes and specific variants associated with decreased enzymatic activity varies across different geographical populations.23, 24, 25 The IM phenotype is observed in approximately 38% of Japanese individuals, but only 10% to 20% of whites, and the predominant CYP2D6 variants contributing to this effect differ between the 2 populations (CYP2D6*4 in whites and CYP2D6*10 in Japanese).23, 24, 32

Across all 3 studies reported in this article, most Japanese participants were phenotypically classified as CYP2D6 EMs, consistent with observations in both Japanese and non‐Japanese populations.26 Based on preliminary findings, CYP2D6 polymorphisms appeared to affect vortioxetine exposure in Japanese adults; however, the interpretation of these findings was limited by the small sample sizes. Subsequent population pharmacokinetic analyses conducted in both Japanese and non‐Japanese cohorts have demonstrated that oral clearance of vortioxetine was approximately 2 times as much in CYP2D6 EMs as in PMs.26 This finding is consistent with that reported in a drug–drug interaction study of vortioxetine and bupropion, a CYP2D6 inhibitor, in which coadministration reduced the clearance of vortioxetine by nearly half.7 Although dose adjustments for vortioxetine are recommended for CYP2D6 PMs and patients taking strong CYP2D6 inhibitors or inducers, the collective findings from these studies do not warrant dose adjustments because of race or CYP2D6 genotype.7, 21

The findings from this study together with those in the literature demonstrated that vortioxetine can be administered with or without food. No clinically significant differences in vortioxetine pharmacokinetics between fasted and fed states were observed at the 2.5‐mg dose (study 1); similarly, drug absorption and elimination of vortioxetine and its metabolites were comparable following administration of 10 mg vortioxetine under fasted and fed conditions (study 3). A subsequent phase 1 study conducted in the United States demonstrated bioequivalence of vortioxetine in the fasted and fed states at the 20‐mg dose, providing further support that there is no food effect on vortioxetine pharmacokinetics.14, 16 Collectively, these findings indicate that food intake had no clinically significant impact on the pharmacokinetics of vortioxetine or its metabolites after a single dose of vortioxetine.

Overall, the safety and tolerability profile of vortioxetine in the Japanese population was comparable to that in the non‐Japanese population. In phase 1 clinical studies conducted in non‐Japanese populations, vortioxetine was tolerated in men and women, but the incidence of AEs was higher in women at doses ≥ 10 mg.15, 19, 26, 33 For this reason, Japanese women in study 1B were administered vortioxetine at lower doses (5 or 10 mg) than those given to men, and only after tolerability at these doses was assessed first in men. Vortioxetine administered as a single dose or multiple doses was safe and tolerated in healthy adults, and no major differences in tolerability were observed between men and women at doses of 10 mg/day or lower. Single doses of 20 and 40 mg and multiple doses of 20 mg were tolerable in healthy men, and similar to what has been reported in non‐Japanese populations, a relatively high incidence of gastrointestinal AEs such as diarrhea and vomiting was observed at the 40‐mg dose.

Conclusions

The findings from our study demonstrate that vortioxetine was slowly absorbed and eliminated following single or multiple oral doses in Japanese adults. No major differences in vortioxetine pharmacokinetics were observed between Japanese men and women, and vortioxetine can be administered regardless of food intake. Importantly, vortioxetine was safe and tolerated in both young adults and elderly populations. Collectively, these studies together with those in the literature indicate that no dose adjustments are required for vortioxetine based on age, sex, or race.

Supporting information

Supplemental Figure S1. Disposition of study participants. Overview of participant disposition in (A) Study 1, (B) Study 2, and (C) Study 3. AE, adverse event; PTE, pretreatment event. Supplemental Figure S2. Vortioxetine concentration‐time profiles. Plasma concentration‐time profiles of vortioxetine following administration of (A) rising doses in healthy males (Study 1A), (B) multiple doses in healthy males and females (Study 1B), and (C) single ‐doses in elderly males and females (Study 2).

Supporting Figure and Tables

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Gina DeStefano, PhD, and Bomina Yu, PhD, CMPP, of inVentiv Medical Communications and supported by Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc., and H. Lundbeck A/S. Publication management support was provided by Sayako Horii and Hiroaki Fukumoto of Takeda Japan Medical Affairs.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

K. Nakamura, Y. Aritomi, and A. Nishimura are employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. K. Matsuno was an employee of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited at the time of this study.

Funding

These studies were supported by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited and H. Lundbeck A/S.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Mental health: Depression. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed July 25, 2016.

- 2. Gelenberg AJ. A review of the current guidelines for depression treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Henkel V, Seemuller F, Obermeier M, et al. Does early improvement triggered by antidepressants predict response/remission? Analysis of data from a naturalistic study on a large sample of inpatients with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;115(3):439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cassano P, Fava M. Tolerability issues during long‐term treatment with antidepressants. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(1):15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ginsberg LD. Impact of drug tolerability on the selection of antidepressant treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(12 suppl 12):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bang‐Andersen B, Ruhland T, Jorgensen M, et al. Discovery of 1‐[2‐(2,4‐dimethylphenylsulfanyl)phenyl]piperazine (Lu AA21004): a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Med Chem. 2011;54(9):3206–3221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen G, Lee R, Hojer AM, Buchbjerg JK, Serenko M, Zhao Z. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), a multimodal antidepressant. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):727–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mork A, Pehrson A, Brennum LT, et al. Pharmacological effects of Lu AA21004: a novel multimodal compound for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340(3):666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pehrson AL, Cremers T, Betry C, et al. Lu AA21004, a novel multimodal antidepressant, produces regionally selective increases of multiple neurotransmitters—a rat microdialysis and electrophysiology study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(2):133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. du Jardin KG, Jensen JB, Sanchez C, Pehrson AL. Vortioxetine dose‐dependently reverses 5‐HT depletion‐induced deficits in spatial working and object recognition memory: a potential role for 5‐HT1A receptor agonism and 5‐HT3 receptor antagonism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(1):160–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mork A, Montezinho LP, Miller S, et al. Vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), a novel multimodal antidepressant, enhances memory in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;105:41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kotlyar M, Brauer LH, Tracy TS, et al. Inhibition of CYP2D6 activity by bupropion. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(3):226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hvenegaard MG, Bang‐Andersen B, Pedersen H, Jorgensen M, Puschl A, Dalgaard L. Identification of the cytochrome P450 and other enzymes involved in the in vitro oxidative metabolism of a novel antidepressant, Lu AA21004. Drug Metab Dispos. 2012;40(7):1357–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Areberg J, Sogaard B, Hojer AM. The clinical pharmacokinetics of Lu AA21004 and its major metabolite in healthy young volunteers. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;111(3):198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dudkowski C, Lee R, Wu R, et al. A phase 1 study to assess the effect of age, gender and race on the pharmacokinetics of single and multiple doses of Lu AA21004 in healthy subjects [abstract no. PII‐48]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012(91):S69. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Y, Wojtkowski T, Agyemang A, Homery MC, Karim A. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of Lu AA21004 in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:1115. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, duloxetine‐referenced, fixed‐dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(4):215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alam MY, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y, Serenko M, Mahableshwarkar AR. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) in major depressive disorder: results of an open‐label, flexible‐dose, 52‐week extension study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(1):36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alvarez E, Perez V, Dragheim M, Loft H, Artigas F. A double‐blind, randomized, placebo‐controlled, active reference study of Lu AA21004 in patients with major depressive disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(5):589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahableshwarkar AR, Zajecka J, Jacobson W, Chen Y, Keefe RS. A randomized, placebo‐controlled, active‐reference, double‐blind, flexible‐dose study of the efficacy of vortioxetine on cognitive function in major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(8):2025–2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang J, Mathis MV, Sellers JW, et al. The US Food and Drug Administration's perspective on the new antidepressant vortioxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dubovsky SL. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of vortioxetine for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(5):759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bijl MJ, Visser LE, Hofman A, et al. Influence of the CYP2D6*4 polymorphism on dose, switching and discontinuation of antidepressants. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65(4):558–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Han KM, Chang HS, Choi IK, Ham BJ, Lee MS. CYP2D6 P34S polymorphism and outcomes of escitalopram treatment in Koreans with major depression. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(3):286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma MK, Woo MH, McLeod HL. Genetic basis of drug metabolism. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2061–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Areberg J, Petersen KB, Chen G, Naik H. Population pharmacokinetic meta‐analysis of vortioxetine in healthy individuals. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115(6):552–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naik H, Chan S, Vakilynejad M, et al. A population pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic meta‐analysis of vortioxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;118(5):344–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fiske A, Wetherell JL, Gatz M. Depression in older adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:363–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boyce RD, Handler SM, Karp JF, Hanlon JT. Age‐related changes in antidepressant pharmacokinetics and potential drug‐drug interactions: a comparison of evidence‐based literature and package insert information. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(2):139–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. World Health Organization . Mental health and older adults. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs381/en/. Accessed July 25, 2016.

- 31. Zanger UM, Raimundo S, Eichelbaum M. Cytochrome P450 2D6: overview and update on pharmacology, genetics, biochemistry. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369(1):23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bradford LD. CYP2D6 allele frequency in European Caucasians, Asians, Africans and their descendants. Pharmacogenomics. 2002;3(2):229–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mahableshwarkar AR, Jacobsen PL, Chen Y. A randomized, double‐blind trial of 2.5 mg and 5 mg vortioxetine (Lu AA21004) versus placebo for 8 weeks in adults with major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(3):217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure S1. Disposition of study participants. Overview of participant disposition in (A) Study 1, (B) Study 2, and (C) Study 3. AE, adverse event; PTE, pretreatment event. Supplemental Figure S2. Vortioxetine concentration‐time profiles. Plasma concentration‐time profiles of vortioxetine following administration of (A) rising doses in healthy males (Study 1A), (B) multiple doses in healthy males and females (Study 1B), and (C) single ‐doses in elderly males and females (Study 2).

Supporting Figure and Tables