Abstract

Peer support is increasingly provided as a component of mental health care, where people in recovery from mental health problems use their lived experiences to provide support to those experiencing similar difficulties. In the present study, we explored the evolution of peer support workers’ (PSW) occupational identities. A qualitative study was undertaken alongside a pilot randomized, controlled trial of peer support for service users discharged from a mental hospital in London, UK. Two focus groups were conducted with eight PSW. Semistructured interviews were conducted with 13 service users receiving peer support and on two occasions with a peer support coordinator. The data were analysed using theoretical thematic analysis, focussing on occupational identity formation. We discuss how the occupational identity of PSW evolved through the interplay between their lived experience, their training, and their engagement in the practice environment in such a way as to construct a liminal identity, with positive and negative outcomes. While the difficulties associated with the liminality of PSW could be eased through the formalization and professionalization of the PSW role, there are concerns that this could lead to an undermining of the value of PSW in providing a service by peers for peers that is separate from formal mental health care and relationships. Skilled support is essential in helping PSW negotiate the potential stressors and difficulties of a liminal PSW identity.

Keywords: liminality, mental health, occupational identity, peer support, peer support worker

Introduction

Peer support is increasingly provided in mental health care, where people who are in recovery from mental health problems use their lived experiences to provide hope and support to those experiencing similar difficulties (Gillard et al. 2013). Peer support can be provided in different formats, ranging from self‐help groups to peer employees (Solomon 2004), with a wide range of approaches identified (Miyamoto & Sono 2012; Myrick & del Vecchio 2016). With growing support for the use of peer support workers (PSW), and discussions on the formalization and professionalization of the role, it is important to explore and understand the evolution of the occupational identities of PSW.

Background

A number of benefits of peer support have been identified. Repper and Carter (2011) identified the following benefits for service users: reduced admission rates; increased empowerment, social support, and social functioning; empathy, acceptance, and hope; and reduced stigma. Benefits for PSW include aiding continuing recovery; personal growth; development of skills and the therapeutic effect of helping others; and for paid PSW, the benefits of being employed (Faulkner & Basset 2012; Walker & Bryant 2013), although some suggest caution in interpreting benefits from predominantly weak evidence (Lloyd‐Evans et al. 2014).

Peer support workers’ occupations are relatively new, developed across a range of settings and from numerous perspectives, and thus face multiple challenges. Moran et al. (2013) identified challenges in three domains: work environment, occupational path, and personal mental health. Workforce challenges relate to a lack of consensus about core competencies, training, or certification requirements (Myrick & del Vecchio 2016). A significant issue is the experience of role conflict and ambiguity resulting from the status of PSW as both ‘service users’ and ‘staff/providers’. Boundary issues have also been identified, including whether to relate to service users as friends or clients, and difficulties with disclosing peer status (Barkway et al. 2012; Faulkner & Basset 2012; Kemp & Henderson 2012; Miyamoto & Sono 2012; Walker & Bryant 2013).

The role of PSW in mental health services is continuing to evolve, with a growing move towards the formalization and professionalization of these roles in order to address traditional power balances and improve accountability (Enany et al. 2013). However, there is debate surrounding professionalization, such as concerns about authenticity and representativeness (Enany et al. 2013), and the value for PSW of training, supervision, payment, and status (Faulkner & Basset 2012). These challenges highlight the difficulties encountered by PSW in the transition into their new role.

The notion of transition is closely linked with redefining a sense of self and the reconstruction of self‐identity (Clarke et al. 2015; Kralik et al. 2006). Thus, an individual's transition from ‘service user’ to PSW will potentially result in a change in identity (Pratt et al. 2006). Identity can be defined as ‘people's subjectively construed understandings of who they were, are and desire to become’ (Brown 2015; p. 20). Identity is generally understood to be in flux, and enacted through language and action, rather than being an indication of an unchanging core self (Brown 2015). Thus, individuals can hold multiple understandings of themselves, incorporating social identities, personal identities, and role identities (Brown 2015; Hughes et al. 2013). These identities are ‘developed and sustained through processes of social interaction’ (Brown 2015; p. 23). In the present study, we discuss the PSW identity as an occupational identity in the context of PSW who are trained for the role of PSW and who work as volunteers or are paid PSW through an organization. Thus, the PSW identity is constructed in relation to a reference group of other PSW and a workspace (Maranon & Pera 2015).

The evolution of an occupational identity has been described as having three components: the personal self, the occupational self, and feedback from others. These components are brought together in a dynamic process, whereby personal attributes are integrated with occupational training, and the emerging occupational identity tested via feedback from others (Auxier et al. 2003; Gibson et al. 2010; Kram et al. 2012; Pratt et al. 2006; Reisetter et al. 2004). No existing research was found that focussed specifically on the identity formation of PSW. In the present study, we explore the formation of a PSW identity; in particular, we identify the formation of a liminal PSW identity in the context of a pilot randomized, controlled trial (RCT) of peer support.

The concept of liminality was developed by the anthropologist Arnold Van Gennep (1909 /1972), and later expanded by Victor Turner (1959). Liminality refers to the transitional states in which individuals are ‘neither here nor there…betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial’ (Turner 1969; p. 95). Turner's (1967) original concept focussed on rituals and processual phases. However, in its application to the organizational context, liminality is commonly understood as ‘a position of ambiguity and uncertainty’ (Beech 2011; p. 287), and used to ‘understand the meanings of being in‐between institutionalized arrangements, taken‐for‐granted socio‐cultural structures, and established social positions’ (Winkler & Mahmood 2015; p. 53).

Methodology

Design

We conducted a qualitative study of PSW and service users (those receiving peer support) as part of a pilot RCT of peer support (Simpson et al. 2014a). PSW provided peer support for 4 weeks to patients discharged from four mental health wards in London, UK. Peer support would be in addition to usual aftercare, and focussed on providing face‐to‐face and telephone support during the transition period from inpatient to community care.

Sample

Potential PSW were recruited via advertising through a mental health service provider and service user organizations. PSW (n = 16) were trained over a 12‐week period (Simpson et al. 2014b), and a small weekly payment was made during training and periods of providing peer support. Thirteen people completed the training, and of those, eight went on to be active PSW (3 withdrew from training after realizing they were not ready for the level of commitment required, 2 were not considered quite ready to work independently with peers, 1 became unwell, 2 others were still waiting for employment‐check clearance). All PSW received supervision and support, and any pre‐existing contact with mental health services continued.

Focus groups were conducted with all PSW (n = 8) at 3 and 7 months from the start of the intervention period. Interviews were also conducted with the peer support coordinator (PSC) at the 3‐ and 7‐month intervals. Potential service user participants were identified by the PSC in discussion with ward staff. Participants (n = 46) were randomly assigned to either the experimental (peer support, n = 23) or control (care as usual, n = 23) condition. Service users in the peer support arm were invited to take part in a short interview 1 month after discharge; 12 service users participated in interviews.

Interview schedules

Semistructured interview schedules for both individual and focus group interviews were developed in collaboration with members of a service user research advisory group (Simpson et al. 2014c). Examples of questions and prompts are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of questions and prompts in interviews and focus groups

| Peer support worker focus group interviews | Peer support coordinator interview | Peer (service user) interviews |

|---|---|---|

|

Question: What has been your overall impression of peer support project? Prompt: How do you think it is going? What has been good about it? Have there been any problems? Anything challenging for you? |

Question: How do you think the peer support workers are getting on? Prompt: Have there been any particular problems? What aspects have worked well? What do they find most enjoyable? What do they not like? |

Question: Can you tell me generally about your experience of peer support? Prompt: Was it helpful or unhelpful at all? |

|

Question: What sort of support are you providing? Prompt: Do you meet up with users? Do you provide telephone support? Recovery work? Anything else? |

Question: How do they get on on the wards? Prompt: Do they have any difficulties with the staff at all? |

Question: What sort of support did you get from the peer support worker? Prompt: Did you meet up? Did s/he phone you at all? Anything else? |

|

Question: What do you most enjoy doing? Prompt: What parts of the role do you really like? Is there anything you don't like? What aspects of the role do you not enjoy? |

Question: What sort of things do they discuss in supervision with you? Prompt: Are there common themes they talk about? |

Question: Would you have liked to have had more of anything? Prompt: What sort of thing would you have liked the peer support worker to have done more? |

|

Question: How do you get on with the ward and community team staff? Prompt: Have there been any particular problems? What aspects have worked well? |

Question: Are there things we should have covered in the training but didn't? Prompt: Are there things that could have done differently in the training? |

Question: How did you feel when the support stopped? Prompt: Did it feel okay or did you miss the extra support? Were you glad it was finished? |

Data analysis

The data were analysed using theoretical thematic analysis. This involved a deductive (‘top down’) approach, as opposed to an inductive (‘bottom up’) approach, to identifying themes or patterns in the data (Braun & Clarke 2006). In particular, the analysis was driven by a theoretical interest in the concepts of identity and occupational identity formation, discussed earlier.

Digital recordings were professionally transcribed, then checked for accuracy. The transcripts were uploaded onto the Dedoose (version 4.3.86; SocioCultural Research Consultants (SCRC), UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA) online qualitative data management programme. There were two main stages to the analysis. The first stage involved: (i) familiarization with the data; (ii) generating codes reflecting the content of the interviews; and (iii) grouping the codes into themes. In the second stage, the themes were interpreted through the lens of research, and theorizing into occupational identity formation (Gibson et al. 2010; Kram et al. 2012; Pratt et al. 2006). All authors were involved in the data analysis.

Ethics approval

Research ethics approval was provided by East London and The City Research Ethics Committee Alpha (ref no.: 10/H0704/9). Research governance approval was also obtained from the participating National Health Service (NHS) Trust.

Results

Demographics

Demographics for service users and PSW are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Service user demographics

| Sex | Age (years) | Ethnicity | Primary diagnosis | Admission status | No. admissions within 12 months | Total no. previous admissions | Living status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 38 | White other | Depression | Informal | 0 | 1–3 | Unknown |

| Female | 48 | Black British | Depression | Informal | 0 | 1–3 | Unknown |

| Male | 31 | Black African | Paranoid Schizophrenia | Detained | 1–3 | 1–3 | Unknown |

| Female | 33 | White British | Depression | Informal | 1–3 | 1–3 | Friends |

| Female | 25 | Black African | Depression | Detained | 1–3 | 4+ | Supported |

| Male | 55 | White British | Paranoid Schizophrenia | Informal | 1–3 | 1–3 | Alone |

| Male | 24 | Black African | Psychosis | Detained | 1–3 | 1–3 | Alone |

| Male | 42 | Mixed | Paranoid Schizophrenia | Informal | 1–3 | 4+ | Alone |

| Female | 42 | Black African | Paranoid Schizophrenia | Informal | 0 | 1–3 | Alone |

| Female | 27 | Black British/African | Unknown | Informal | 1–3 | 1–3 | Parents |

| Male | 46 | Mixed | Paranoid Schizophrenia | Detained | 1–3 | 4+ | Alone |

| Male | 45 | White British | Depression | Informal | 0 | 0 | Alone |

| Male | 20 | Black European | Schizoaffective disorder | Informal | 1–3 | 1–3 | Parents |

Table 3.

Peer support worker demographics

| Sex | Age (years) | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 43 | White Irish |

| Female | 44 | White other |

| Male | 32 | Bangladeshi |

| Female | 32 | Black Caribbean |

| Male | 55 | White British |

| Male | 40 | White British |

| Female | 47 | White British |

| Male | 40 | White British |

We found that the PSW identity evolved through the interplay between the three components of an occupational identity discussed in the literature—the personal self of the PSW, occupational training, and feedback from others—in such a way as to construct a liminal identity. In what follows, we present the themes ‘personal self: lived experience’, ‘occupational training’, and ‘PSW in practice: identity and relationships in the practice environment’. This is followed by a discussion of the formation of a liminal PSW identity. Due to the transcriber not identifying which participants were speaking during the focus groups, quotes from interviewees are simply identified with ‘service user’, ‘PSW’ and ‘PSC’.

Personal self: Lived experience

This theme refers to the role of the lived experience of PSW having a mental illness on their emerging PSW identity. The PSW discussed the importance of being ‘one of them’ (PSW) and being able to ‘get it’ (PSW). They described identifying themselves to their peers as a service user, and using their lived experience to help their peers ‘because you understand, you've been there, done that, worn the t‐shirt’ (PSW). Similarly, services users identified the importance of having somebody who is ‘not connected with the doctors or the consultants or the nurses and stuff’, and somebody ‘that I can relate to’ (service user). Seeing that the PSW had ‘come through and he…seems to be got on (sic) with his life’ (service user) demonstrated that ‘somebody that (has a) mental health issue…can get better and be okay, and you can work as well’ (service user).

However, some PSW also wanted to move past this previous identity, with some reluctant to talk in detail about their mental health problems. Becoming a PSW fostered the development of a new identity, one they could be proud of and that has greater social/cultural value:

Do you know what I really like? Being able to tell people that I'm a mental health peer support worker and I work…for the NHS, instead of ‘Oh, I'm on (government financial support)’. (PSW)

Thus, the lived experience of PSW played an important role in the emerging PSW identity, both as a point of entry into the role and as a point of departure from service user to ‘worker’. The training provided through the RCT also played a role in the evolution of the PSW identity.

Occupational training

The training for PSW was delivered via 12 weekly 1‐day sessions (Table 4) (Simpson et al. 2014b).

Table 4.

Peer support worker training programme

| Session no. | Session name |

|---|---|

| 1 | Exploring peer support |

| 2 | Tree of life: life stories |

| 3 | Recovery and personal recovery plans |

| 4 | Recovery and personal recovery plans continued |

| 5 | Confidentiality, information sharing, exploring boundaries |

| 6 | Active listening skills |

| 7 | Social inclusion |

| 8 | Appreciating difference |

| 9 | Responding to distressing situations |

| 10 | Revisiting boundaries & difficult situations—participants’ choice |

| 11 | Preparing to be a peer supporter |

| 12 | Endings and celebrations |

The PSW discussed the importance of training in their evolution from service user to PSW, particularly in terms of legitimizing their identity as a PSW: ‘I'm a peer support worker, I've got my shiny badge; I've been trained’ (PSW). The training also gave participants the confidence to work as a PSW: ‘Yeah, it gave me a basic level of confidence and a little body armour to go out into the big, wide world’ (PSW).

In addition the training helped develop expectations about the PSW role. For example, one PSW discussed his experience of being expected by his peer to fix his problems with his government financial support. He reflected on the PSW role in relation to this expectation:

And when I stepped back…I thought, ‘Hang on, my role is to encourage him to actually look into his benefit stuff himself’. (PSW)

Overall the PSW were very positive about the way their training prepared them for their role. However, they saw training as only one facet in the development of their PSW identity, which needed to be combined with experience in the practice environment: ‘It's something that you do; you learn it and you get better as you, the more you do it’ (PSW).

PSW in practice: Identity and relationships in the practice environment

Participants found that the PSW practice environment provided them with experiences that, while at times reinforcing their training, often challenged their preconceptions and required them to reinvent what it means to be a PSW. The PSW described their role in the practice environment as providing practical support, emotional support, and support in mental health recovery. The main focus of the PSW role was on outings with peers, with a small amount of money provided to PSW to enable this. In addition to what the PSW did with their peers was the formation of relationships with others in the practice environment, particularly service users (peers), staff, and the PSC. These relationships played a key role in the evolution of the occupational identity of PSW, and were the topic of extensive discussion in the interviews.

Relationships with peers

The relationship between PSW and their peers was described as the most important feature of being a PSW. Relationships developed over time, and were generally seen as having a positive effect on service users. The role allowed PSW to form a different relationship to that between a service user and professional; a supportive relationship through which they could provide a unique service where they could spend the time focussed solely on their peers, and where the service users knew they would not be judged:

He felt he could talk to me because he felt I didn't have an agenda…and therefore, he would open up a lot more to me than he would with the staff. (PSW)

The importance of ‘being one of them’ (PSW) in the development of a positive relationship could be seen in situations where PSW were identified as staff members, rather than specifically PSW, leading to unsatisfactory outcomes:

I think (service user) saw me, I was just another member of staff…so, yeah, we didn't even get any meaningful conversation at all. (PSW)

Through the process of socializing with someone who has had similar experiences, the PSW–service user relationship often developed into one resembling friendship:

It wasn't…professional, and I think that's what they appreciate the most, just a friend. (PSW)

It's like having a mate, a friend, you know? (Service user)

The participants generally viewed this type of relationship positively. However, there could also be negative effects. Developing ‘friendships’ with peers was particularly problematic with the ending of the relationship, with some service users wanting to continue the ‘friendship’ and feeling ‘very sad, very, very sad’ (service user) and ‘gutted’ (service user) once the relationship ended. Similarly, the friend‐like relationship led some PSW to feel as though they had mistreated their peers, as they too felt loss at the ending of the relationship: ‘I felt like I'd dumped somebody’ (PSW).

Not being identified as a member of staff by peers could also lead to problems in PSW–service user relationships, particularly with regards to uncertainty about the nature of the relationship and maintaining boundaries. For example, one PSW discussed his discomfort with being offered support by one of the service users he was supporting. Participants also identified uncertainty on the part of peers about the PSW role and their relationships, leading to unmet expectations about what the PSW would do for them (e.g. helping them move house). PSW themselves were at times unsure of what the peer was to them: ‘And you're not a real friend, and that's when you feel, ‘God, I'm not really that, either’ (PSW). This uncertainty could lead to PSW feeling like they were being taken for granted by their peers: ‘I just feel like a certain lack of respect’ (PSW). Thus, while the participants described positive outcomes of the PSW–service user relationship, there were issues they were keen to explore relating to the multiple identities of PSW: staff, service users, and ‘friends’.

Relationships with staff

The multiple roles occupied by PSW could also lead to difficulties in their relationships with other members of staff. PSW discussed differences in how they were treated by staff on the wards, with some staff being welcoming and respectful, while others ignored them. Being ignored meant that PSW felt like outsiders, rather than part of a team of people working together for the benefit of service users:

I felt like an outsider; nobody spoke to you, nobody in the staffroom spoke to you. (PSW)

However, some PSW, while feeling like they were not treated as part of the health‐care team, also articulated that, as a PSW, ‘you're supposed to be independent of that really’ (PSW).

PSW also described a lack of respect for their role on the part of some staff members, with the PSC also discussing uncertainty in relationships between PSW and other staff, and difficulties PSW experienced with being ignored by staff. The expectation of PSW that they would be welcomed on the ward highlights the complexity of the PSW role and the issues associated with being both an insider (staff) and an outsider (service user). In order to overcome these issues, the PSC suggested a more formal approach to identifying PSW to staff. PSW, too, found that being formally introduced and attending meetings led to them being:

recognized by the staff…that was really important….Once you've got an identity, it's hard to treat you like a piece of furniture. (PSW)

Relationship with the PSC

The relationship with the PSC was another key factor in the development of the occupational identity of PSW. Over the course of the project, the PSC provided training, coordination, support, and supervision, and liaised with staff and service users on the wards. Thus, the role of the PSC in identity formation was to reinforce what PSW had learned through their education, but also to address any issues that arose during practice.

The PSW discussed the value of having ongoing support to work through problems in the practice environment as they tried to navigate their roles and relationships with service users and staff: ‘I think, where there were gaps…the supervision covered it’ (PSW). Given the dual role of PSW as both mental health service users and staff, the PSC also provided support for PSW with any personal or mental health problems they might have. This added a degree of complexity to the PSC–PSW relationship, as discussed by the PSC:

I think initially when I started, I was very reluctant, because I saw the peer support workers as staff. I felt a little bit reluctant to ask about their mental health. (PSW)

Thus all participants – the PSW themselves, their peers, and the PSC – experienced uncertainty with regards to the the multiple roles occupied by PSW. The complexity of the PSW role leading to the formation of a liminal identity is now discussed.

Formation of a liminal identity

The PSW described themselves as providing a valuable and effective service for people with a mental illness, as meeting a need, and therefore, as individuals who make a valuable contribution to enhancing the lives of others with a mental illness.

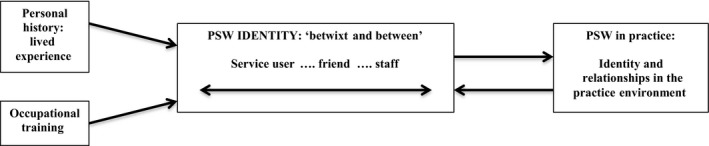

However, this emerging identity was in flux due to the complexity of the PSW role that developed over the course of their practice, where PSW viewed themselves, and were viewed by others, as service users, friends, and staff. We found, therefore, that the occupational identity of the PSW evolved through the interplay between their personal history (lived experience), educational history, and the practice environment (in particular, their interpersonal interactions) in such a way as to construct a liminal identity (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Liminality in the occupational identity of peer support workers (PSW): Being ‘betwixt and between’.

The notion of being ‘betwixt and between’ (Turner 1969; p. 95) identities was evident in the PSW identities articulated in the interviews:

I think (service users) were thinking I would help them make complaints, but I wasn't going to do that because I'm part of the team. Although I'm separate, I'm still a part of the NHS team as well….It's difficult because I was in the middle….You have all the professionals, then you have the peer, and then you're in between them. (PSW)

As a peer support worker, you're kind of straddling between mental health support worker and a befriender, and you're on this continuum, and it's, it must be quite difficult. (PSW)

There were positive effects of this liminal identity identified in the interviews. As two PSW discussed, the PSW role is able to fill in the gaps between other support services available to service users:

It's kind of extra bits, isn't it, that fills the gap that other…staff and family don't reach, if that makes sense. It's because you're not them, you're kind of an ‘us’, but you're still kind of– (PSW1)

–in the middle somewhere. (PSW2)

Positive effects identified by service users included being able to socialize with and confide in peers whom they can trust, and developing the confidence that they, too, can experience recovery from mental illness. Positive effects on PSW of being both service users and staff included the confidence and positive sense of self gained from merging their own personal experiences with the skills needed to work with others to support them to achieve a positive outcome.

There were also negative effects of a liminal PSW identity. Being both a friend and not a friend, both a staff member and not a part of the team, and both a service user and a staff member, meant that at times PSW were also none of these things. In addition, as discussed earlier, there were difficulties for others – service users, staff, and the PSC – in terms of how they could or should relate to PSW. A major issue related to endings, where peers and PSW experienced distress with the ending of relationships that were more like friendships than professional relationships.

Discussion

In the present study, we explored the formation of a PSW identity in the context of mental health care. The results demonstrate how the lived experience and occupational training of PSW interact with their practical experience in the formation of a liminal occupational identity. This reflects the dynamic process of the evolution of an occupational identity, where personal attributes are integrated with training, and the emerging occupational identity tested via feedback from others (Auxier et al. 2003; Gibson et al. 2010; Kram et al. 2012; Pratt et al. 2006; Reisetter et al. 2004).

Lived experience of having a mental illness is fundamental to the PSW role, and thus, the PSW identity. However, the PSW role also allowed them to shift their identity from service user to employee. As Hutchinson et al. (2006) discussed, there is a cultural value in this shift, where people working as peer providers ‘often re‐conceptualize their identity from someone who is ill, incapable, disabled and disempowered to one who is legitimate, empowered and validated’ (p. 206). For the PSW, training played an important role in legitimizing their new identity, and gave them the confidence to work in their new role. Training is an important element in the evolution of an occupational identity, described as a professional socialization process through which individuals identify with their professional group and develop group norms and values (Clarke et al. 2015; McNeil et al. 2013).

Also of importance is the interplay between training and practice in the development of a strong occupational identity (Clarke et al. 2015; Davis 2006). In the practice environment, the formation of relationships with service users, staff, and the PSC was a key element to the development of the PSW identity, as suggested in the literature (Auxier et al. 2003; Gibson et al. 2010; Pratt et al. 2006; Reisetter et al. 2004; Russell et al. 2010). In fact, external validation of identity through relationships in the work/practice environment is reported to be more important for those less experienced in their work, such as the PSW participants in the present study, than those with greater experience (Kram et al. 2012; Moss et al. 2014).

Through the interplay between their personal history (lived experience), educational history, and the practice environment, the participants were able to begin the process of forming a PSW identity. Yet this was an identity in flux due to the multiple roles played by PSW in being service users, friends, and staff. This meant that the emerging PSW identity was in fact a liminal identity, where their identities lay ‘betwixt and between’ these roles. Given that the PSW role is divergent and still developing, this raises the questions of whether, and to what extent, this liminality can or should be resolved.

While traditional liminality refers to a temporary state, liminality in the context of occupational roles can relate to a temporary period of liminality (i.e. when a temporary agency worker moves to permanent employment) or a permanent situation, depending on the occupational role and context (Garsten 1999; Nissim & De Vries 2014; Ybema et al. 2011). Liminality research in the occupational context highlights the negative consequences associated with being in a permanent state of liminality and the importance of having the ‘structure and support to reach aggregation’ (Beech 2011, pp. 299–300).

Our participants identified both positive and negative outcomes associated with a liminal PSW identity. People in liminal states often find they cannot relate to either sociocultural position (Auton‐Cuff & Gruenhage 2014), and this was apparent when participants discussed uncertainty about who they are in their relationships and who they should be. This was particularly borne out in dealing with ending the PSW–service user relationship, which was difficult for both PSW and service users. Yet the positive effects on both PSW and their peers garnered through shared experiences and trust, and the capacity of the role to fill in the gaps between other supports available to service users, were seen as important.

In traditional liminality, the rituals themselves constrain the uncertainty associated with the liminal state, and therefore, reduce the stress experienced by the liminal (Beech 2011). The need to introduce greater formality and structure into the PSW–staff relationship was suggested as a means of reducing the difficulties experienced by PSW in their relationships with staff. Having the support of a mentor who can guide the liminal through established ritual processes is another element of traditional liminality that helps ease stress (Beech 2011). The importance of support by the PSC was found in the present study to help PSW negotiate the practice environment.

Formalization and professionalization of the PSW role is another way in which the negative aspects of a liminal PSW identity could be eased. However, as discussed earlier, there are concerns that this could lead to an undermining of the value of PSW in providing a service by peers for peers that is separate from formal mental health care and relationships. Those developing PSW programmes will need to carefully weigh up the pros and cons of professionalization, and put into place safeguards to ensure the integrity of the PSW role, while addressing the potential stressors and difficulties of a liminal PSW identity.

Limitations

A limitation of the present study was that all PSW were new to the role; more established peer workers might have found ways of negotiating and resolving some of the tensions described. Peer support is being increasingly used across a range of health‐care conditions, demonstrating positive benefits for service users in various settings (Doull et al. 2005; Jackson et al. 2015). The findings from the present study might have resonance beyond mental health.

Conclusion

In the present study, we explored the PSW identity in the context of mental health services. The results revealed that the emerging PSW identity was a liminal identity, where PSW lay ‘betwixt and between’ the multiple roles played by PSW in being service users, friends, and staff. Many of the rituals that are usually involved when adopting an occupational role might be more nuanced and complex for PSW, given their reliance on a status associated with their lived experience. Thus, attempts to ‘professionalize’ the PSW role might be problematic, and require careful thought to ensure the well‐being of individuals and the future success of peer support initiatives.

Relevance for Clinical Practice

Introducing PSW roles within or alongside clinical mental health teams, and ensuring their development and healthy growth, require planning, consideration, and skill. Organizational toolkits are being introduced that aim to help all involved to identify important values and principles, and shared expectations of the peer support role (Peer Worker Research Team, 2015). Such approaches need to be adopted flexibly to suit the needs of the role and context, and in light of the present study, should also aim to recognize and explore the challenges of the liminal identity, and how best to support people taking on such valuable yet challenging roles.

Acknowledgement

The project was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit programme (RfPB PB‐PG‐0408‐16151). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

References

- Auton‐Cuff, F. & Gruenhage, J. (2014). Stories of Persistence: The Liminal Journey of First Generation University graduates. In: Higher Education Close UP 7. http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/events/hecu7/papers/auton-cuff.pdf. [Cited 2 December 2016].

- Auxier, C. R. , Hughes, F. R. & Kline, W. B. (2003). Identity development in counselors‐in‐training. Counselor Education & Supervision, 43, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Barkway, P. , Mosel, K. , Simpson, A. , Oster, C. & Muir‐Cochrane, E. (2012). Consumer and carer consultants in mental health: The formation of their role identity. Advances in Mental Health, 10, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Beech, N. (2011). Liminality and the practices of identity reconstruction. Human Relations, 64, 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. D. (2015). Identities and identity work in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17, 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C. , Martin, M. , de Visser, R. & Sadlo, G. (2015). Sustaining professional identity in practice following role‐emerging placements: Opportunities and challenges for occupational therapists. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 78, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. (2006). The importance of the community of practice in identity development. The Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 4, 1–8. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/ijahsp/vol4/iss3/5/ [Cited 28 April 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- Doull, M. , O'Connor, A. M. , Welch, V. , Tugwell, P. & Wells, G. A. (2005). Peer support strategies for improving the health and well‐being of individuals with chronic diseases. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, Art. No.: CD005352. [Google Scholar]

- Enany, N. E. , Currie, G. & Lockett, A. (2013). A paradox in healthcare service development: Professionalization of service users. Social Science & Medicine, 80, 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, A. & Basset, T. (2012). A helping hand: Taking peer support into the 21st century. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 16, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Garsten, C. (1999). Betwixt and between: Temporary employees as liminal subjects in flexible organizations. Organization Studies, 20, 601–617. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, D. M. , Dollarhide, C. T. & Moss, J. M. (2010). Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of new counselors. Counselor Education & Supervision, 50, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gillard, S. G. , Edwards, C. , Gibson, S. L. , Owen, K. & Wright, C. (2013). Introducing peer worker roles into UK mental health service teams: A qualitative analysis of the organisational benefits and challenges. BMC Health Service Research, 13, 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, N. , Locock, L. & Ziebland, S. (2013). Personal identity and the role of ‘carer’ among relatives and friends of people with multiple sclerosis. Social Science & Medicine, 96, 78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, D. S. , Anthony, W. A. , Ashcraft, L. et al (2006). The personal and vocational impact of training and employing people with psychiatric disabilities as providers. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29, 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, D. , Peters, K. , Andrew, S. , Daly, J. , Gray, J. & Halcomb, E. (2015). Walking alongside: a qualitative study of the experiences and perception of academic nurse mentors supporting early career nurse academics. Contemporary Nurse, 51, 69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, V. & Henderson, A. R. (2012). Challenges faced by mental health peer support workers: Peer support from the peer supporter's point of view. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 35, 337–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralik, D. , Visentin, K. & Van Look, A. (2006). Transition: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 55, 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kram, K. E. , Wasserman, I. C. & Yip, J. (2012). Metaphors of identity and professional practice: Learning from the scholar‐practitioner. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 48, 304–341. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd‐Evans, B. , Mayo‐Wilson, E. , Harrison, B. et al (2014). A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maranon, A. A. & Pera, M. P. I. (2015). Theory and practice in the construction of professional identity in nursing students: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 35, 859–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, K. A. , Mitchell, R. J. & Parker, V. (2013). Interprofessional practice and professional identity threat. Health Sociology Review, 22, 291–307. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, Y. & Sono, T. (2012). Lessons from peer support among individuals with mental health difficulties: A review of the literature. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 8, 22–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, G. S. , Russinova, Z. , Gidugu, V. & Gagne, C. (2013). Challenges experienced by paid peer providers in mental health recovery: A qualitative study. Community Mental Health Journal, 49, 281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss, J. M. , Gibson, D. M. & Dollarhide, C. T. (2014). Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of counselors. Journal of Counseling Development, 92, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Myrick, K. & del Vecchio, P. (2016). Peer support services in the behavioural healthcare workforce: State of the field. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39, 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissim, G. & De Vries, D. (2014). Permanent liminality: The impact of non‐standard forms of employment on workers’ committees in Israel. International Labour Review, 153, 435–454. [Google Scholar]

- Peer Worker Research Team . (2015). Introducing Peer Workers into Mental Health Services: An Organisational Toolkit. London, St George's: University of London; http://www.peerworker.sgul.ac.uk/knowledge-mobilisation-initiative/St%20Georges%20Peer%20Worker%20Organisational%20Toolkit.pdf. [Cited 2 December 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M. G. , Rockmann, K. W. & Kaufmann, J. B. (2006). Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar]

- Reisetter, M. , Korcuska, J. S. , Yexley, M. , Bonds, D. , Nikels, H. & McHenry, W. (2004). Counselor educators and qualitative research: Affirming a research identity. Counselor Education & Supervision, 44, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Repper, J. & Carter, T. (2011). A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 20, 392–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, V. , Wyness, L. A. , McAuliffe, E. & Fellenz, M. (2010). The social identity of hospital consultants as managers. Journal of Health Organization & Management, 24, 220–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A. , Flood, C. , Rowe, J. et al (2014a). Results of a pilot randomised controlled trial to measure the clinical and cost effectiveness of peer support in increasing hope and quality of life in mental health patients discharged from hospital in the UK. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 30 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A. , Quigley, J. , Henry, S. J. & Hall, C. (2014b). Evaluating the selection, training, and support of peer support workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52, 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A. , Jones, J. , Barlow, S. & Cox, L. (2014c). Adding SUGAR: Service user and carer collaboration in mental health nursing research. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 52, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20131126-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P. (2004). Peer support/peer provided services: Underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27, 392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. (1959). The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti‐Structure. Chicago: Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. W. (1967). Betwixt and between: The liminal period in Rites de passage. In: Turner V. (Ed). The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. (pp. 93–111). Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, V. (1969). From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. Chicago: Aldione. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gennep, A. (1909. /1972). The Rites of Passage. Translated by M. Visedon & G. Caffee. Chicago: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G. & Bryant, W. (2013). Peer support in adult mental health services: A metasynthesis of qualitative findings. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36, 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, I. & Mahmood, M. K. (2015). The liminality of temporary agency work: Exploring the dimensions of Danish temporary agency workers’ liminal experience. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 5, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ybema, S. , Beech, N. & Ellis, N. (2011). Transitional and perpetual liminality: An identity practice perspective. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34, 21–29. [Google Scholar]