Abstract

A growing literature highlights complexity of policy implementation and governance in global health and argues that the processes and outcomes of policies could be improved by explicitly taking this complexity into account. Yet there is a paucity of studies exploring how this can be achieved in everyday practice. This study documents the strategies, tactics, and challenges of boundary‐spanning actors working in 4 Sub‐Saharan Africa countries who supported the implementation of multisectoral nutrition as part of the African Nutrition Security Partnership in Burkina Faso, Mali, Ethiopia, and Uganda. Three action researchers were posted to these countries during the final 2 years of the project to help the government and its partners implement multisectoral nutrition and document the lessons. Prospective data were collected through participant observation, end‐line semistructured interviews, and document analysis. All 4 countries made significant progress despite a wide range of challenges at the individual, organizational, and system levels. The boundary‐spanning actors and their collaborators deployed a wide range of strategies but faced significant challenges in playing these unconventional roles. The study concludes that, under the right conditions, intentional boundary spanning can be a feasible and acceptable practice within a multisectoral, complex adaptive system in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Keywords: boundary‐spanning actors, complex adaptive systems, multisectoral nutrition, nutrition governance, policy implementation

1. INTRODUCTION

There is growing interest in the recent literature to apply complexity thinking to health policy, planning, implementation, evaluation, and overall governance.1, 2, 3, 4 This literature convincingly demonstrates that health systems have complex adaptive system (CAS)–like properties, argues that improved performance and outcomes could be achieved by explicitly taking these properties into account, and provides some guidance and tools for doing so. While the current literature is convincing at the conceptual level and is generating increasingly powerful tools for quantitative analysis of system dynamics,5 there is a paucity of studies examining whether and how complexity can be taken into account as a practical matter in the everyday practice of issue governance. This is especially challenging when the institutional structures and “rules of the game” for addressing a multisectoral problem are still based on bureaucratic and hierarchical institutions and assumptions.6, 7, 8, 9 One strategy involves the use of boundary‐spanning actors (BSAs) who may enhance the performance of a CAS by sharing information, facilitating common understanding, and managing relationships and who can generate trust and commitment and help problem‐solve and innovate.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 While theoretically promising, there is a paucity of case studies examining the experience of BSAs in the context of low‐ and middle‐income countries.16 This paper seeks to address these gaps in the complexity and BSA literatures through an examination of experiences with multisectoral nutrition (MSN) in 4 Sub‐Saharan African countries. Nutrition is an appropriate focus because of intensive efforts underway to operationalize a multisectoral approach in a large number of countries, but the findings are relevant for a large number of other multisectoral health conditions, such as overweight and obesity, noncommunicable diseases, HIV, malaria, road safety, alcohol and substance abuse, and domestic violence.

2. UNDERNUTRITION AND MULTISECTORALITY

Maternal and child undernutrition is a major risk factor for mortality and disability‐adjusted life years on a global basis, is the leading risk factor in Sub‐Saharan Africa, and has negative impacts on cognitive development, school learning, adult health and productivity, and national economic growth.17, 18 This, combined with evidence on the efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of a number of interventions,19, 20 has contributed to the ascendancy of nutrition at the national and international levels. Examples include the Sustainable Development Goals, which include a target to end malnutrition in all its forms by 2030; the Nutrition for Growth Compact in 2013 that generated over $4B in commitments for high‐priority nutrition interventions; the Second International Conference on Nutrition with representatives from more than 170 governments; a number of landmark resolutions and targets from the World Health Assembly; and high‐level commitments from governments in over 59 countries currently in the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) movement.21

With the agenda‐setting and commitment‐building phases well underway, there is an urgent need to generate scientific and practical knowledge on how to design, strengthen, and implement effective systems, strategies, and interventions to address these problems on a large scale. The strategy promoted by the SUN movement and adopted in principle by all or most SUN countries is multisectoral.22 This involves a combination of nutrition‐specific interventions (eg, micronutrient supplements and the promotion of appropriate breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and hygiene practices) and efforts to improve the nutrition sensitivity of policies and programs in health, agriculture, education, social protection, and industry/trade among others.23 In keeping with current discourse and global agreements concerning development cooperation,24, 25, 26 the SUN movement places great emphasis on strengthening nutrition governance by promoting the principles of country‐owned and country‐led strategies and greater alignment of technical, operational, and financial support from development partners.

The nutrition community has embraced this view of the problem for nearly a quarter century but over the same period has faced persistent governance challenges at global and national levels.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 This is because of the involvement of multiple ministries, sectors (public, private, nongovernment organization [NGO]), stakeholders, administrative levels (community to national and global), dispersed loci of control, and dynamic networks of power and influence among actors. The “ecosystem” of individuals and institutions involved in the multisectoral governance behaves like a CAS, which makes it difficult to govern exclusively through the formal and hierarchical (legal and bureaucratic) institutions commonly established to address the problem (eg, multisectoral coordinating committees). Recent work in 3 SUN countries has documented significant challenges in operationalizing MSN through formal committees and conventional procedures, owing to weaknesses in leadership, coordination, collaboration, human resources, awareness, advocacy, and financing but stopped short of recasting the problem in terms of CASs.34, 35, 36, 37

3. NUTRITION GOVERNANCE IN CASs

The SUN movement is guided by strategic objectives that emphasize a strong and coherent policy and legal framework, a common results framework, effective multisectoral coordination platforms, and sufficient domestic resources, supplemented with external assistance. The movement also promotes explicit engagement principles (transparency, inclusiveness, mutual accountability, consensus orientation, continuous communication, learning and adapting, cost‐effectiveness, rights‐based). These are broadly similar to principles articulated in the broader governance literature (Appendix A)38, 39 and identified from country case studies on nutrition.28, 40, 41 These sources are helpful for indicating what conditions or principles should exist or be put in place for effective governance. But there also is a need for knowledge and guidance on how to put them in place in the real world of multistakeholder CASs where power, authority, knowledge, interests, and incentives are dispersed, diverse, dynamic, and conflictual. For instance, how can the conditions for effective governance be created when executive leadership is not committed to the agenda, when the “soft skills” for managing consensus and disagreements among technical and bureaucratic stakeholders are weak and/or staff are already overcommitted with existing mandates and responsibilities?

A small body of empirical work in nutrition highlights the importance of strategic capacity, leadership, entrepreneurship, and similar qualities on the part of midlevel actors.28, 42, 43 These qualities have been helpful in catalyzing or facilitating progress in national or subnational settings, with an emphasis on dealing with complexity, applying system thinking, crossing institutional boundaries, and adapting to the situation at hand, in line with the literature outside of nutrition.9, 10, 16, 44, 45, 46 These findings from nutrition research have strong resonance with the literature on “boundary spanners,” who are seen as potentially important actors who, as noted earlier, can enhance the performance of a CAS by sharing information, facilitating common understanding, managing relationships, generating trust and commitment, problem‐solving, and innovating.10, 11, 12, 13 The present study was undertaken to better understand the roles, strategies, and tactics and challenges of BSA working to advance national, MSN agendas. The paper examines the experiences in 4 African countries where a BSA was introduced into the nutrition policy ecosystem in each country, as an explicit intervention into a CAS to facilitate the efforts of other stakeholders to implement the country's MSN policies, plans, and programs.

The specific objectives of this paper are to describe (1) the overall country accomplishments, enabling conditions and challenges in implementing MSN, as a context for the work of the BSA; (2) the informal strategies and tactics used by the BSAs; and (3) the challenges faced by these BSAs and the coping strategies they used to manage them. The paper concludes with suggestions for future practice and research related to CASs and MSN.

4. MATERIALS AND METHODS

4.1. African Nutrition Security Partnership

This study took place in the context of the African Nutrition Security Partnership (ANSP). The ANSP was a European Union–funded project implemented from 2011 to 2015 through the United Nations (UN) Children's Fund (UNICEF) regional offices in west/central Africa (West and Central Africa Regional Office) and eastern and southern Africa (Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office) and the country offices in the 4 participating countries: Burkina Faso, Mali, Ethiopia, and Uganda. The overall purpose of ANSP at country level was to assist in developing, strengthening, and implementing MSN policies, plans, and/or programs. The intent was to complement and strengthen what was already being done by government and partners, with modest amounts of funding (approximately 20M Euros) distributed across 4 countries and 2 subregional UNICEF offices for 4 years, provided directly to governments through the UNICEF country offices. A statistical profile of the 4 countries is provided in Appendix B.

4.2. Cornell's role, positionality, and overall approach

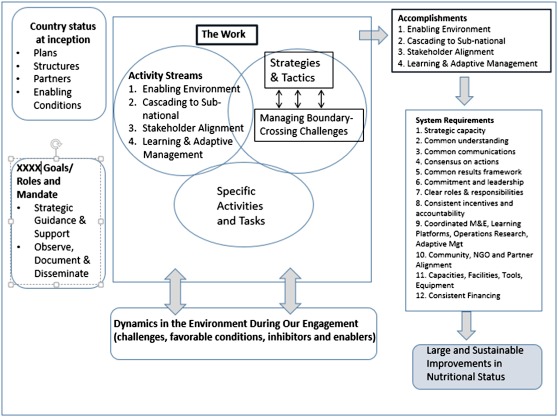

Cornell University was contracted by the UNICEF regional offices to (a) provide strategic guidance and support to the government officials and development partners in the nutrition policy community and (b) observe, document, and disseminate lessons from country experiences. Three staff members (H.H.u.R., D.S., J.T.) were posted to ANSP countries during the final 2 years of ANSP for this purpose (1 each in Ethiopia and Uganda and 1 for both Burkina Faso and Mali). Although the ANSP project has been implemented through UNICEF, these staff played the role of independent BSAs rather than being dedicated and accountable to any single development organization, and their work was approached as an opportunity to discover the realities of boundary‐spanning work in real‐world contexts. Their mandate was to help the country—meaning the government and its partners—to succeed in developing and implementing an effective MSN system and to document the lessons for internal and external audiences. The BSAs were granted an unusual degree of flexibility in how they approached this, but in broad terms, they all focused on promoting a systems view of MSN, identifying strategic bottlenecks, gaps, and opportunities within the system, bringing these to the attention of stakeholders that could take action upon them and serving as honest brokers of information and guidance within the policy community, following the principles of developmental evaluation.47

The identities, skills, and positionality of BSAs are important factors that can facilitate or inhibit their work because of its inherently relational nature and their embeddedness within complex policy stakeholder systems. The 3 country‐based BSAs in this project were recruited following an international search and interview process that emphasized relationship management with diverse policy stakeholders and relevant prior work experience, with a preference given for nationals from the respective countries. One (D.S.) was a Burkinabe national with a PhD in international nutrition who supported Mali and Burkina Faso; another (J.T.) was a Ugandan national with a PhD in development sociology who supported Uganda; and a third (H.H.u.R.) was a Pakistani national with an MA in economics and MPA (public administration) who supported Ethiopia. As noted, they were positioned as honest brokers of information and guidance within the policy community, building upon the recognized reputation of the principal investigators and Cornell University for prior work in international nutrition. The BSAs were mentored and supported through weekly Skype calls, 4 campus retreats, and 1 to 2 visits per country by these 2 PIs (D.P. and S.G.) based at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY. By virtue of its connections to the BSAs and the US‐based staff, Cornell University itself was an indirect stakeholder within the nutrition policy communities in these 4 countries and had multiple influences on the work of the BSAs as described in this paper.

4.3. Research methods

We approached this work from an action research orientation to gain insight into the realities and dynamics of the early stages of national multisectoral work in general and boundary‐spanning work in particular. In formal terms, our study is a holistic, revelatory, multiple‐case study,48 focused on 2 objects of analysis: (1) the country experiences (in terms of accomplishments, enabling conditions, and challenges in implementing MSN) and (2) BSAs (in terms of their strategies and tactics as BSAs, their challenges working as BSAs, and their strategies for managing these BSA challenges). For research purposes, the country experiences and the BSA experiences were both treated as emergent phenomena with a complex set of political, historical, sociocultural, bureaucratic, and interpersonal influences and interactions. Because of this complexity, this paper primarily seeks to describe, classify, and understand these phenomena, rather than attempt a systematic analysis of causal influences, but selected examples of such influences are noted when warranted by the available evidence. Data collection, analysis, and interpretation were guided by constructs from the policy sciences framework and complexity principles as applied to developmental evaluation.47, 49

Data were collected in a prospective fashion from participant observation, complemented with end‐line semistructured interviews and document analysis.50 Participant observation was especially rich and diverse because the BSAs interacted with a variety of the MSN stakeholders on a regular basis over a 2‐year period. The most frequent interactions (usually daily or weekly) were with key nutrition staff in the organizations that provided office space or administrative support or that were responsible for coordinating the multisectoral effort. This was the Office of the Prime Minister in Uganda, the Ministry of Health in the other 3 countries, and to varying degrees the UNICEF country office in all 4 countries, along with the ANSP‐implementing NGOs in Western Africa. There also were frequent (eg, weekly) informal interactions with an “MSN subset” consisting of the 3 to 5 most active nutrition stakeholders from governments, UN agencies, and/or NGOs. Beyond the MSN subset, there were regular or periodic informal interactions with many other nutrition stakeholders in the course of performing the boundary‐spanning work. These interactions all were focused on implementation issues, ranging from identifying bottlenecks and strategizing how to overcome them to the planning of workshops, trainings, or other events at national or subnational levels. In addition to these informal interactions, the BSAs attended many or most MSN‐related meetings of the multisectoral coordinating bodies and partner organizations, as well as conferences or workshops at national or subnational levels. Semistructured interviews were conducted in the last few months of the project with a total of 36 individuals ranging from national‐level current or former staff members in the Ministry of Health (MOH) (including a number of Nutrition Directors), other line ministries, Office of the Prime Minister (in Uganda), UN agencies and bilateral organizations, members of district‐level MSN coordinating committee members, local NGOs implementing MSN, and consultants to government or other implementing agencies (Appendix C). The primary documents informing this paper are the current or historical government policies, plans or programs, decrees for MSN, MSN committee meeting notes, donor and NGO reports, and MSN workshop reports.

Several techniques were used to strengthen the data and interpretations emerging from the participant observation. As noted, the Ithaca‐based staff had weekly Skype calls (of 1 to 1.5 h) with each of the BSAs to discuss the progress and bottlenecks during the week, strategize on next steps, and provide them ongoing mentoring and support. In addition to strengthening the “action” side of the action research, these calls allowed for deeper interrogation of the BSA observations, experiences, assumptions, and interpretations, in effect stress testing their participant observations as well as helping the staff to retain an insider‐outsider perspective in their work.51 These calls were audio‐recorded and generated 149 audio files that were transcribed then coded and analyzed using the software Atlas.ti. A second method for validating and extending the emergent data and interpretations was the extensive interaction between the BSA and the MSN subset noted above, whose members served as key informants and a source of triangulation throughout the period in the field. A third method was the peer debriefing that occurred during the 4 retreats, where the entire Cornell team tabulated, compared, and interrogated the emergent findings from each country and placed them within a progressively more sophisticated and nuanced analytical framework (Appendix D). Finally, stakeholder member checks were conducted through 3 project‐wide meetings of the key UNICEF and government staff where the emergent findings were presented, challenged, and modified.

The findings for this paper are presented in relation to the analytical framework that emerged from the final staff retreat (Appendix D). The country accomplishments and enabling conditions are presented on a country‐specific basis, while the challenges faced by the countries and by the BSAs are aggregated across countries. The aggregation is done in part because many of the challenges are common across countries and in part to preserve and respect individuals' and countries' identities and confidentiality. This study was approved by Cornell University's Institutional Review Board on July 19, 2013.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Institutional situation at inception

The 4 countries differed in many respects and had some features in common at the time of inception (Table 1). They differed in relation to the existence of policies and plans authorizing and detailing the design of the MSN: Ethiopia and Uganda had formalized multisectoral plans in place, Mali had adopted its national nutrition policy (NNP) with a multisectoral lens and was in the process of developing its multisectoral action plan, and Burkina Faso had an NNP and strategic plan that was health sector focused rather than multisectoral. They differed in the status of multisectoral structures: Ethiopia and Uganda had established political and technical structures at the national level and authorized (but not yet implemented them) at the subnational level; Mali's policy anticipated political and technical structures for nutrition at national and subnational levels, but these were not yet in place; and Burkina Faso had consultation committees at the national and subnational levels. The MSN coordinating structure was anchored in the MOH in 3 of the countries (Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Mali) and in the Office of the Prime Minister in Uganda. A successful working model of MSN at district level existed in Ethiopia, for use as illustration in cascade training in the regions, but such a model did not yet exist in the other 3 countries. Government leadership on the nutrition agenda was strong in Ethiopia and still emergent in Uganda. Development partners were exercising strong influence on the nutrition agenda in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Uganda, but much less so in Ethiopia. In terms of commonalties, all 4 countries had previous experience with sectoral (health) or bisectoral (health and agriculture) approaches for addressing malnutrition, but with varied success and without the benefit of the policy, government, and partner interest seen in the current period. In all cases, development partners were active in nutrition but not well aligned with each other or the government. None of the countries possessed detailed MSN implementation guidelines, and all of them had placed responsibility for its coordination on the shoulders of a very small number of already‐over‐committed staff. Finally, the level of understanding or interpretation of “MSN” was generally weak or highly variable in all 4 countries. Considered together, these features mean that much work remained in each country in creating an effective MSN system (as articulated in Appendix E), and the challenges and the openings for addressing them were quite different across the 4 countries. Accordingly, the strategies for moving the MSN forward in each country needed to be sensitive to these differences and responsive to the challenges and opportunities that presented themselves over time.

Table 1.

Institutional situation at inception

| Burkina Faso | Mali | Ethiopia | Uganda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legislatively authorized multisectoral policy | National nutrition policy 2008 but health centered | Yes, national nutrition plan 2013 | No | Draft form since 2003 |

| Politically endorsed multisectoral plan/strategy | Nutrition strategic plan 2011 but Health centered | Multisectoral nutrition action plan 2014 in development (not yet endorsed) | Revised National Nutrition Program 2013 | Uganda Nutrition Action Plan 2010 |

| Anchorage | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health | Office of the Prime Minister |

| Multisectoral structures | National: unilevel consultative only, dedicated to nutrition‐specific interventions | National: anticipated in the policy, not yet in place | National: dedicated bilevel and sectoral coordination structures | National: dedicated bilevel coordination structures |

| Subnational: consultative only, dedicated to nutrition‐specific interventions | Subnational: anticipated in the policy, but not yet in place | Subnational: not yet | Subnational: in process at the district level | |

| Functionality of the structures (meeting frequency and attendance) | National: irregular | National: not yet | National: partial | National: irregular |

| Subnational: in a few regions, which began since 2008 | Subnational: not yet | Subnational: not yet | Subnational: needed strengthening | |

| Terms of reference and guidelines for structures and focal points | National: partial | National: not yet | National: in draft form | National: not yet |

| Subnational: not yet | Subnational: not yet | Subnational: in draft form | Subnational: not yet |

5.2. Country accomplishments, enabling conditions, and challenges

During the time of this study, some accomplishments were observed in each country in relation to strengthening the enabling environment at the national level and cascading to the subnational level as shown in Table 2. In broad terms, these fall into 3 categories: (a) the creation or reform of institutions at national or subnational levels such as coordinating structures, anchorage arrangements, implementation teams, sectoral working groups, or formal alliances; (b) addition of multisectoral dimensions to preexisting policies, programs, plans, mandates, and indicators; and (c) a variety of “soft” accomplishments related to progress in aligning policies, programs, and/or approaches as well as improvements in multisectoral awareness, commitments, convergence, ownership, capacity, actions on bottleneck, advocacy, and so on. The hard accomplishments are ones that could be objectively verified and/or reported because they have a paper trail documenting the progress and/or are codified in official documents. Many of them were initiated during the 2‐year period of this study, but some, such as the reform of coordinating structures or addition of multisectoral dimensions to existing policies or programs, involved many prior years of advocacy, debate, and deliberation. The soft accomplishments, in contrast, often do not leave a paper trail, represent rather nuanced changes, can also take months or years to emerge, and would be difficult or impossible to objectively document or verify. In many cases, they involve a shift in mindset in a small number of key individuals, which appeared as breakthroughs or critical moments in the participant observation data and led to new or invigorated efforts in a positive direction. For instance, a UNICEF staff member previously uninterested in MSN, while mainly concerned with nutrition‐specific interventions, became a leader for the development of multisectoral approaches in the country. As another example, after participating even briefly in a sensitizing workshop on MSN, an MOH secretary became positively impressed by the progress of the MSN actors and invited the MSN technical committee to present a working plan for an MSN implementation team that he could later prioritize in his budget.

Table 2.

Accomplishments: strengthening the enabling environment and subnational cascading

| Country | Accomplishment | |

|---|---|---|

| Strengthening the Enabling Environment | Subnational Cascading | |

| Burkina Faso | MSN awareness and government commitment increased, S |

Infant and child feeding program as an entry point for MSN, S MSN platform formed in the Yako district, H MSN platform operationalized in the Yako district, (H) |

| Government ownership and leadership strengthened | ||

| Coordinating structure reformed (awaiting final signature), (H) | ||

| Progress in making the nutrition policy and strategy multisectoral, (H) | ||

| Development of a common result framework in process, (H) | ||

| Strengthening nutrition sensitivity of sectoral policies in progress, (H) | ||

| Civil society alliance for nutrition created, H | ||

| Infant and child feeding program became more multisectoral, (H) | ||

| Mali | MSN action plan developed, launched, and disseminated, H | MSN platform created and coordinating committees formed in the Bankass and Yorosso districts, H |

| Coordination structures formed, H | Subdistrict platforms formed, H | |

| National coordinating structures operationalized, (H) | Subdistrict platforms operationalized, (H) | |

| Civil society alliance for nutrition formed, H | Capacity for cascading strengthened in the national team, S | |

| Functionality of MSN committee and funding gaps assessed, S | Expansion to other districts in the Sikasso region underway, (H) | |

| Progress in aligning policies and programs, S | Capacity to mainstream nutrition in local development plans strengthened, S | |

| Full‐time implementation unit created and awaiting staff appointments, (H) | 3 national actors trained as certified instructors in participatory evaluations and strategic planning and MSN group facilitation, S | |

| Uganda | Strengthened capacity for coordinating the MSN action plan, S | Strengthened implementation structures in 5 districts, S |

| Stakeholder convergence concerning MSN anchorage, S | Strengthening local government planning for MSN in 5 districts, S | |

| Strengthened government ownership for nutrition, S | Learning platforms for MSN formed in 5 districts, (H) | |

| Strengthened national implementation team, (H) | Integration of nutrition indicators in district development plans in 5 districts, H | |

| Bottlenecks identified and being addressed at national and district levels, S | Stakeholders in 5 districts fully engaged in creating MSN guiding principles, including the supports districts need from the national level, S | |

| Formal agreement by government and partners on guiding principles for MSN implementation, H | The progress and learning in these 5 districts profoundly shape the guiding principles subsequently agreed upon at the national level, H | |

| Ethiopia | NNP launched (2013) and revised (2015), H | Official dissemination of NNP to all 9 regions, H |

| High‐level MSN coordination body formed, H | Official launch of NNP by senior regional officials, H | |

| Regular and effective meetings of high‐level body, (H) | MSN structures created and focal points assigned in 4 regions, H | |

| MSN Technical Committee formed, H | Cascading workshops in 4 regions, zones, and woredas and menu of intervention workshops held at the zonal level, H | |

| Strengthened common understanding among members of the Technical Committee, S | Regional learning platforms formed, (H) | |

| Sectoral working groups formed in some ministries, (H) | MSN integrated into annual review meetings and supportive supervision, H | |

| Nutrition advocacy for parliamentarians and First Lady Ambassador, S | ||

| Draft MSN implementation guidelines developed and launched, (H) | ||

Abbreviations: H, hard accomplishment; (H), hard accomplishments in progress; MSN, multisectoral nutrition; NNP, National Nutrition Program; S, soft accomplishment.

A set of enabling conditions were present in each country before and/or during the study period, with a number of common items across countries (Table 3). These enabling conditions were identified through the weekly Skype calls and retreats with the field staff and then grouped into 4 categories for presentation purposes, adapting a framework for microinstitutionalization of policies.52 The MSN agenda in each of the countries appeared to be assisted by a combination of conditions (specifically, the existence of high rates of malnutrition); top‐down signals, commitment, and/or pressure (to varying degrees); support, evidence, and/or advocacy from international partners and initiatives; and a wide variety of factors internal to the nutrition policy community. The latter relate to favorable relationships, prior experience and capacities, favorable understandings of the malnutrition problem, and the existence of strong or supportive organizations (government and partner) at subnational levels. The distinction between “hard” and “soft” factors, as seen in the accomplishments, is also relevant with the enabling conditions. Indeed, the vast majority of the enabling conditions shown here would be classified as soft because they revealed themselves in the course of the participant observation, but few of them would be codified in formal documents. Yet they were seen to be critical for enabling progress in small or large ways, by creating new openings or overcoming previous bottlenecks. For example, in 1 country, national‐level authorities decided at the last minute to join in a short district‐level workshop where the new MSN policy was being presented. Serendipitously, this exposure enamored them with MSN, and they then accelerated the organizing of MSN efforts at the national level.

Table 3.

Enabling conditions for progress in each country

| Country | Enabling Conditions |

|---|---|

| Burkina Faso |

High levels of malnutrition (C) Commitment and leadership from the MOH (Director of Nutrition, SUN focal point, Director General, General Secretary, Minister, and a regional director) (Int) Prior experience with the sectoral consultation platform (Int) Some favorable relationships among local actors (Int) Critical deadlines for policy revision (Int) A large, experienced NGO (SEMUS) (Int) Favorable staff turnover in key positions (C) Financial incentives (real or perceived) for sectors, NGOs, and individuals (Int/Ext) Country commitment to global initiatives, ie, SUN movement (Int/Ext) REACH arrival in the country (Ext) Strong support from donors and the partner and technical platform (Ext) |

| Mali |

High level of malnutrition and the “Sikasso paradox” (C) Favorable momentum and progress with the policy, action plan, and coordination structures (Int) Decree establishing MSN structures (Int) Flexibility and openness of members of the coordinating structure to explore all opportunities to learn and advance the agenda (Int) Commitment and leadership of central and local authorities (Int) Strong presence of some credible partners in the district (UNICEF and the ASDAP NGO) (Int/Ext) Strong support from donors and partners and technical forum (Ext) REACH presence in the country (Ext) Country commitment to global initiatives, ie, SUN movement (Int/Ext) Government commitment to ending malnutrition (Int) |

| Uganda |

High levels of and long‐standing malnutrition (C) Government acceptance of country‐owned, country‐led approach (Int) High‐level political commitment and support from the President and Prime Minister (OPM), holding others accountable (Int) Country experiences with earlier attempts at MSN (Int) Availability of reference materials (policy/program documents) (Int) Action plan as a reference document for MSN implementation (Int) Earlier decision to have OPM as anchorage (Int) Well‐established government structures: OPM, sectors, districts, and below (Int) Directive from OPM to orient all districts by a deadline (Int) Earlier experiences with multisectoral coordination from HIV/AIDS (Int) Ability to build on some ongoing activities in 5 districts (Int/Ext) Country commitment to global initiatives, ie, SUN (Int/Ext) Strong support from some donors and development partners (Ext) |

| Ethiopia |

High rates of malnutrition (C) Momentum for transitioning from emergency response to development approach to nutrition (Int) Endorsement of NNP by State Ministers and pressure to launch and cascade to regions, reinforced by their request for progress markers to monitor and create accountability (Int) Political expectation to reach NNP goals and align them with high‐level government goals and strategies (Int) Existence of positive examples of MSN working at the woreda level for use as an inspiration and examples in regional workshops (Int) Existence of regional universities as potential partners on regional learning platforms and for operations research; regional buy‐in for university involvement because of past research on nutrition (Int) Existence of strong partners at the regional level to advocate for and support cascading (Int/Ext) Strong support from some donors and development partners (Ext) Global dialogue and evidence on MSN helped get high‐level buy‐in (Ext) |

Abbreviations: C, conditions; Ext, external; Int, internal; MOH, Ministry of Health; MSN, multisectoral nutrition; NGO, nongovernment organization; NNP, National Nutrition Program; OPM, Office of the Prime Minister; REACH, Renewed Efforts Against Child Hunger and Undernutrition; SUN, Scaling Up Nutrition; UNICEF, United Nations Children's Fund. Adapted from Moseley and Charnley.52

Despite the impressive list of enabling conditions within each country, progress was not steady over time or uniform across all activity streams and stakeholders. To the contrary, progress was routinely delayed, halted, or reversed by a large number of challenges (Table 4). These exist at the level of individuals, organizations, and the overall system and most of them relate to the factors internal to the nutrition policy community rather than at the macropolitical level. At the individual level, some of them relate to capacities, while others relate to micropolitics. At the organizational level, some of the challenges again relate to limited capacity or experience with MSN or nutrition in general; others reflect that in most cases nutrition has not even begun to be integrated (institutionalized) into the administrative architecture of the ministries (viz, job descriptions, staff positions, alignment of objectives, and integration into planning and reporting); and yet other challenges stem from administrative or bureaucratic procedures and inefficiencies in general. At the system level, a number of challenges relate to the functionality of the coordination platforms (“horizontal coordination”), the cascading of MSN to subnational levels (“vertical coordination”), and broader system features (disagreements, poor alignment, excessive donor influence, and lack of shared vision and commitment to country‐centered strategy and ownership).

Table 4.

Challenges experienced in building the MSN systems (aggregated across countries and activity streams)

| Level | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Individual level |

Varied understanding of the multisectoral nature of malnutrition Varied commitment to stunting reduction Lack of experience aligning sectoral mandates and funding priorities with nutrition Capacity constraints in some key positionsa Gatekeepers as bottlenecks Risk aversion by selected influential actors Fear of loss of control over nutrition agenda Resistance from some actors within government and some donors Micropolitics, power struggles, and personal agendas |

| Organizational level |

Lack of knowledge in sectors of their contribution to nutrition Lack of alignment between sectoral objectives and MSN objectives Sector‐specific indicators and planning with no common framework Overreliance on sectoral focal points to stimulate nutrition sensitivity Sectoral focal points that are of low level, different from one meeting to another, overcommitted, and unable to influence their ministrya Lack of nutrition in job descriptions and/or poor specificity Nutrition objectives in national development plans but not supported by appropriate indicators, strategies, and funding High staff turnover in key positionsa Funding: levels, sources, dynamics, inflexibility, and unpredictability (eg, to fund meeting venues, consultants, and sitting fees) Bureaucratic inefficiencies with organizing small and large meetings Bureaucratic procedures and resistance in bringing consultants into the country even when they are needed |

| System level |

Coordination structures weak or not in place Platform meetings with poor attendance, frequency, facilitation, and follow‐up Time required for structures to become functional Time required to develop sector understanding and commitment Lack of clear roles and responsibilities for staff and structures Disagreements over anchorage Weak convening power and authority for MSN in MOH Health focus of the nutrition operational agenda Weak cascading approaches (“train and hope”) Lack of detailed implementation guidelines Lack of harmonized orientation guidelines for sectors and districts Weak reporting mechanisms for MSN from district to national levels Disagreements within the nutrition policy community Absence of inclusive process in developing key plans, strategies Scheduling conflicts, too many meetings, too few staffa Partner mandates that do not align with government or each other Excessive influence of donors on government agendas and priorities Government not in the driver's seat Very few strategic team players at the national levela Lack of a shared long‐term vision for MSN Lack of a real and shared commitment to country‐owned, country‐led approaches Irregular and poorly attended meetings of the high‐level body Weak tracking, reporting, and accountability to the high‐level body |

Abbreviations: MOH, Ministry of Health; MSN, multisectoral nutrition.

These challenges all point to a serious gap in human resources to support the MSN effort.

The challenges in Table 4 are aggregated across the 4 countries, in part because the vast majority are common across countries. This comprehensive presentation, which provides a grounded sense of some features and dynamics of a CAS, is daunting to even review and contemplate. The cumulative effect of these daily, weekly, and persistent challenges, on staff assigned responsibility for building the MSN system, was overwhelming. The most persistent challenges were those related to staffing and capacity bottlenecks at organizational and system levels. In all 4 countries, the responsibility for creating the MSN system has been assigned to a very small number of staff who are already fully committed with preexisting responsibilities and have little or no experience with MSN. This reality, which has been noted previously,30, 34, 37, 42, 53, 54 was the rationale for seeking experience with BSAs as a possible high‐leverage strategy for facilitating country progress.

5.3. Boundary‐spanning strategies, challenges, and coping strategies

This section presents our experiences with a BSA intervention, organized in terms of the strategies and tactics our staff used, the challenges they faced in this role, and the coping strategies they used in response to the challenges. An example from one of the countries is provided in Appendix F to illustrate how some of the BSA strategies and tactics interact with challenges when a BSA works with other members of the MSN subset to create or strengthen a component of the MSN system.

The BSA strategies and tactics, when analyzed through reflection exercises at several points during the study, were organized into 4 categories (Table 5). Within the first category (overall orientation, values, and strategies), the BSAs manifested the generic characteristics that are inherent in that role.10, 11, 46 In addition, they enacted several strategies specific to the needs of MSN, such as reinforcing government ownership, working with sectors and specific actors to help them clarify their roles and responsibilities, and “building capacity” by enhancing the understanding of MSN through informal conversations, small‐group meetings, workshops, conferences, emails, and all other opportunities that presented themselves or could be created. The second category, relationships, was a fundamental requirement for the BSAs to be effective in their roles. It involved creating and managing their own relationships with various actors as well as fostering good working relationships among actors. This is at the core of the “micropolitics” noted in Table 4, was an almost daily struggle, and was never “complete.” The coping strategies and assets for this are discussed below. The third and fourth categories are more concrete actions that were mobilized in proactive and in responsive ways to address specific bottlenecks or achieve specific objectives. Many of these were identified, designed, and deployed in concert with other members of the MSN subset, while others (notably some of the tools) were designed by the Cornell team and deployed by the BSA. For instance, a simple decision matrix was used in one country to help nutrition stakeholders evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of various institutional (anchorage) arrangements for MSN. In another country, a set of context‐specific progress markers was developed (at the request of politicians on the high‐level coordinating body) to facilitate stronger reporting and accountability. And in all 4 countries a “Land Cruiser metaphor” was used and presented in dozens of venues, to help stakeholders see and approach MSN as a system‐building challenge.

Table 5.

Boundary‐spanning actor strategies and tactics for addressing the MSN challenges

| Strategies | Tactics |

|---|---|

| 1. Overall orientation, values, and strategies |

Generic: Embeddedness and networking in stakeholder community Continuous assessment, feedback, and follow‐up Reflective exercises and moments with stakeholders Issue selection at national and subnational levels Assisting stakeholders when asked, to build goodwill Credit giving, not credit taking Risk taking and weighing risk/benefit Knowledge brokering Bridging coordination and communication gaps MSN specific: Re‐enforcing the norm of country owned/country led Strengthening government ownership of the agenda Continuous advocacy with the sectors Clarifying roles and responsibilities for MSN Responsive and opportunistic capacity building Engaging effective consultants Inspiring national authorities via subnational examples and initiatives |

| 2. Relationships |

Effective collaboration with the MSN “subset” Alliance building at all levels and in all sectors Stimulating the creation and/or strengthening of strategic alliances Outreach to individuals to build understanding and buy‐in Managing misunderstandings and disagreements among stakeholders Helping or ensuring that people can “save face” |

| 3. Using opportunities |

Experience‐sharing visits Venue shopping Critical moments and opportunities Critical deadlines Building and maintaining momentum Candid reporting to the high‐level bodies Informal communication with higher‐level officials Attendance of high‐level officials at global meetings Engaging nutrition champions Partnering with ongoing initiatives in the country |

| 4. Tools and activities |

Decision making tools Sensitizing tools SWOT analysis Progress markers Innovative workshop tools Using evidence Initiating stakeholder surveys Effective presentations Goal‐oriented sensitization workshops and meetings Goal‐oriented district‐ and national‐level workshops for alignment of sectors and partners Promoting and supporting collaborative planning |

Abbreviations: MSN, multisectoral nutrition; SWOT, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

In addition to these relatively visible and instrumental contributions of BSAs, their presence in the nutrition stakeholder community provided some more subtle but no less important contributions, some of which are intimated in Table 5. Within the category of knowledge brokering, in one country, the language of “country‐owned, country‐led” (as used in the SUN movement) was introduced to a senior stakeholder, who used it to good effect over the subsequent months to urge greater collaboration among development partners; in another country, the views of district officials were shared with national authorities to help design a consensus approach to MSN; and in one of the project‐wide meetings with all 4 countries present, the sharing of progress in 3 of the countries stimulated the team in the fourth country to overcome some internal disagreements and more fully embrace the intent of MSN. Within the category of informal communication, the BSA's became trusted sources of expertise and candid assessments of progress and bottlenecks in each of the countries and were sought out by selected higher‐level officials in government and NGOs. And within the categories of building alliances and managing disagreements, the BSAs were able to catalyze strong subnational MSN working groups in one country, help overcome a high‐level disagreement about institutional anchorage in another country, and convert a competitive or conflictual situation into a collaborative one in a third country. In general terms, the BSAs became resource persons on MSN, and their expertise was sought after, be it for advice, facilitation, reflection, and the making of easily understood MSN presentations at meetings or for their use of sensitizing tools, mobilizing capacity, wisdom and clear vision of MSN, and listening capacity. Many MSN stakeholders confided in the BSAs, providing them with a unique understanding of goals, interests, or struggles among selected MSN stakeholder; this, in turn, enabled the BSAs to facilitate productive dialogue and for the community of stakeholders to progress towards consensus building and advance MSN implementation. In these and other examples, the contributions stemmed from the “overall orientation, values and strategies” noted in Table 5 and were made possible because the BSAs had the mandate and flexibility (and skills) to act in this way. Equally important, the BSAs had developed and maintained good working relationships with a subset of MSN stakeholders who were strategically located in various organizations, possessed valuable insider knowledge and relationships of their own, created access and opportunities for the BSA, and were active participants in the developing and enacting strategies and tactics to address MSN challenges.

These BSA roles and contributions were not without challenges, however, as detailed in Table 6. Some of the challenges were inherent in the nature of the role itself (eg, the ambiguity; lack of formal authority, control, or resources; and complete dependency on other actors and organizations). A second set of challenges relates to the fact that relationships are at the center of all the BSA's work and some stakeholders perceived the BSA as more of a threat to their personal, professional, or organizational interests than a benefit. This is especially the case when there are disagreements about MSN itself, including questions of anchorage, leadership, implementation strategies, resource control, and the like. In some cases, these relationship challenges were further complicated or compounded by certain identities of the BSA, such as age, gender, national or expatriate status, and jealousy regarding international training and employment. The relationship‐ and identity‐based challenges, while being partially rooted in structural factors, were not completely defined by those factors and were not constant over time. In each of the 4 countries, there were stakeholders who occupied the same structural space (eg, as defined by organization and age/gender/national identity), some of whom were detractors or obstructers of the BSA (or MSN generally) and others of whom were strong allies and supporters; in both categories, some remained in that mode throughout the period of engagement while others moderated or even reversed. This placed the BSAs in a perpetual and emotionally difficult state of managing personal and political relationships and capital, as noted in other accounts of BSA practice.15, 55, 56, 57

Table 6.

Challenges of boundary‐spanning and coping strategies and assets for managing them

| Boundary‐Spanning Challenges | Coping Strategies and Assets for Managing Boundary‐Spanning Challenges |

|---|---|

|

Inherent features

Actual work out of synch with initial work plan and the country reality Stress and ambiguity of working in an emerging context with no clear direction and plan Maintaining the insider/outsider approach when personal interests get in the way of the ultimate goal Dependency on others with authority to convene meetings Limited staffing and lack of control over key partners' planning, scheduling, and convening Patchy administrative support because no own country office Lack of official mandate in the country Bureaucratic rigidity and delays limit our effectiveness Staff turnover requires constant renewal of sensitization efforts, advocacy, and strategic partners Weak capacity within government and other stakeholders limits our effectiveness All possible solutions face a new round of bottlenecks Supporting 2 countries created insufficient physical presence in country at times Relationships Others with poor understanding of our unique role Managing personal/social and professional relationships Perceived competing roles by some stakeholders Political interference in our work from some people Gatekeeping dynamics and manipulation at different levels Lack of collaboration at some points from some partners who were key to our work Riskiness in alliance building and partnerships at the national level Historical alliances for nutrition governance can impede the time it takes to understand peoples motivations and hidden agendas How to handle requests to join certain initiatives, alliances, or cliques that would compromise our neutrality Earning government trust Identities Age, gender, expatriate, international PhD, international position Negative stereotypes about academic research that is extractive or exploitive and adds no practical value |

Reputation

Continually clarify our unique roles and responsibilities Reinforce and demonstrate that we have no separate agenda other than playing a supportive role to the country as a whole Focus on results and remain true to our core values: neutrality, inclusiveness, respect of all partners and their potential contributions Build your own credibility and respect Identities and associations Selectively draw credibility and respect from association with Cornell and the team Selectively draw informal power by association with certain government or partner organizations without identifying too closely with them Some challenges simply need time for our identities and authenticity to emerge from our work and how we conduct ourselves Personal qualities and orientations Patience, interaction, and communication skills Motivation and passion to help your own country maintain morale during the many difficult personal moments Ability to take risks, cope with challenges, adjust, and keep moving forward Knowledge, skill development, and contextual analysis Mentoring from larger Cornell team Identify local mentors and continuously seek their advice and inputs Use intermediaries to understand and help address the issues Keep referring back to developmental evaluation principles Carefully study people and systems Assess peoples' intentions first, rather than assuming they are facilitators of the process just because of their position Try to understand the reason for not collaborating Behaviors, practices, and tactics Accommodate to partner needs first; give credit, do not take it Persistent attempts to collaborate Strategically plan with partners to get government buy‐in through informal relations Form and draw upon strategic allies; do favors to build goodwill Create and/or seize opportunities Provide support out of our mandate without any incentives or expectations Bring in external consultants to build collaborative capacities in others Funder and employer understanding, flexibility, and support Appreciation of systems, complexity, and need for a responsive, emergent approach Flexible goals, strategies, spending rates, reporting requirements, accountabilities Willingness to defend the approach from/to higher ups |

These challenges related to BSA roles and identities became a topic of discussion within the Cornell team from the earliest months of the project, remained as such for the duration, and stimulated corresponding discussions, reflections, and strategizing during weekly Skype calls and team retreats concerning how to best manage them. These coping or management strategies are summarized in 5 categories: reputation, identities and associations, personal qualities and orientations, knowledge, skills and analysis, and behaviors, practices, and tactics (Table 6). Some of these, such as reputation and identities and personal qualities initially may seem to be relatively fixed characteristics of individuals. But the experience revealed the need and the opportunity for these to be actively managed, in the moment and over time, in order to overcome some of the BSA challenges. This is most obvious in the case of reputation, in which the core values such as neutrality, inclusiveness, and respect could be revealed through the actions of the BSA, eventually earning the trust, respect, and support of most stakeholders. But the opportunity also existed to actively (and carefully) manage some of these, as in the case of drawing credibility, respect or power “by association,” with their employer (Cornell) or some of the government organizations or NGOs in the country working on MSN (such as the Office of the Prime Minister, MOH, or UNICEF). Alternatively, this could take the form of creating a sense of distance from one or another organization or its reputation. In other words, “neutrality” was not a static concept or position for a BSA working in the midst of diverse and ever‐evolving interests and agendas. It was a dynamic construct that was actively managed in ways that could build or maintain constructive relationships consistent with the overall goal of advancing MSN.

A second set of strategies and assets (knowledge, skills, and contextual analysis and behaviors, practices, and tactics) initially may appear to be qualities that can be acquired by training and experience, but in fact, they depend on having certain deep orientations and personal qualities. The 3 individuals in these positions were chosen based on evidence of their social and emotional intelligence, rather than their expertise or credentials in nutrition, and this proved to be essential for their work. Another vital element was their access to a selected few mentors or confidants in the country as well as the other members of the Cornell team (the other BSAs as well as the team leaders based at Cornell). These mentors, confidants, and team members provided technical, strategic, and social/emotional support to help endure if not manage the BSA challenges.

Finally, the role of the proximate funder (UNICEF), the employer (a university), and the orientation of the Cornell team leaders (as action researchers) were critically important, for providing the necessary flexibility, support, and “space” to play this BSA role. In particular, the key staff in the regional UNICEF offices understood the necessary and distinctive role the BSAs were playing, trusted the Cornell team to pursue its dual mandate of supporting as well as documenting/learning, and, through largely informal means, moderated the more rigid planning, budgeting, disbursement, reporting, and accountability procedures used in conventional development projects.

6. DISCUSSION

This paper makes three distinctive contributions. First, it confirms the challenges of implementing national MSN approaches as noted by many others30, 34, 37, 54, 58, 59, 60 while extending our understanding by drawing attention to the importance of soft or intangible accomplishments; the importance and context‐dependent nature of enabling conditions; the sheer number and variety of challenges at the individual, organizational, and system levels; and, thus, the time required to achieve the tangible outcomes (eg, in reducing malnutrition) that dominate the focus of politicians, funders, and other stakeholders. These observations have important implications for all current efforts (by the SUN movement and other organizations at national and international levels) to sustain and support progress, including advocacy, target setting, capacity building (at all levels), monitoring and evaluation (M&E), and financing.

Second, the fine‐grained documentation of the change process (ie, the ways in which enabling conditions, challenges, and stakeholder dynamics interacted to produce or inhibit progress) vividly confirms that MSN does indeed exhibit the properties of a CAS (eg, emergence, coevolution, interdependence, path dependence, nonlinearity, and unpredictability). While previous work has identified many of the same challenges with MSN, albeit at higher levels of generality, it has generally stopped short of reconsidering the very nature of the problem and the complex adaptive nature of the systems involved. As noted in the introduction to this paper, the literature convincingly demonstrates that health (and other) systems have CAS‐like properties and argues that improved performance and outcomes could be achieved by explicitly taking these properties into account. The present paper provides empirical evidence to that effect—firmly grounded in contrasting country experiences with MSN rather than theoretical arguments—and can stimulate discussion among national and global actors concerning practical strategies for “taking these properties into account.”

Finally, this paper provides insights concerning one such strategy, in the form of BSAs. The remainder of the paper focuses on this aspect, integrating observations from the present study with insights from the literature to make suggestions for future practice and research.

There are many forms and definitions of boundary spanning. The roles, practices, and challenges of the BSAs in this project closely followed those described by Williams.61, 62 He defines boundary spanners as “individuals who have a dedicated job, role or responsibility to work in a multi‐agency and multi‐sectoral environment and to engage in boundary‐spanning activities, processes and practices.” He goes on to describe 4 types of roles and associated practices, including networking, diplomacy, brokering, risk taking, negotiating, listening, framing, and sensemaking, trust building, conflict resolution, coordinating, and convening. He notes that BSAs “bring together a diverse set of people from divergent professional, sectoral and organizational backgrounds under the umbrella of common purpose. However, this often masks materially different views and opinions on a range of fundamental issues; problem definition and solution; value and belief systems; culture, language and ways of working.” The resonance with the BSAs in this project are obvious, and the present study makes several distinctive contributions.

First, while most of the current literature on BSAs is based on experiences in high‐income countries, the present study is based in a very different context (Sub‐Saharan African), involves significant national and cultural diversity within that context (across the 4 countries and between East and West Africa), and arguably involved a distinctive and much higher degree of complexity (viz, the number and variety of sectors, stakeholders, and organizations). This suggests that, under the right conditions and with a number of qualifications, intentional boundary spanning can be a feasible and acceptable practice within a multisectoral CAS in these contexts. The conditions and qualifications that seemed to allow and facilitate this in the present case include partnership with a well‐regarded organization (UNICEF) at country level; flexibility and space to innovate, granted by the proximate sponsor (UNICEF regional offices); connections with a university recognized for its work in nutrition and the commitment of the team to a collaborative, action research approach; the strategy of working with and through a small number of stakeholders from different organizations in each country (the MSN subset) in virtually all aspects of the work; the personal characteristics and orientations of the BSAs themselves; and the mentoring and support (technical, strategic, and emotional) provided to the BSAs through the Cornell team and key stakeholders within the countries. None of these conditions were an unqualified panacea at all times, in all places, and with all stakeholders, but on balance, they played important enabling roles.

A second contribution lies in the fine‐grained documentation of the boundary‐spanning practice (Tables 5 and 6). The literature extensively discusses BSA orientations and personal qualities, as well as practices,10, 11, 57, 61, 62 but some of the practices and challenges identified here are particular to these contexts and important for guiding future work. Moreover, many of the coping strategies that emerged in this project appear particular to these contexts and represent a further unique and important contribution. These strategies allowed the BSAs to persevere, learn, and become more effective in the face of the many challenges and, as importantly, provided the social and emotional support required in the position. The stresses of boundary spanning are noted in the literature,10, 55, 56, 61, 63 but in very different contexts, and any future efforts in the present contexts must anticipate this need.

Third, the experiences in these four countries, all of whom are part of the SUN movement, allow us to identify a small number of critical bottlenecks that, if addressed, would significantly accelerate progress: anchorage capacity, implementation teams, and high‐level engagement. In all four countries, the responsibilities for MSN coordination and oversight were assigned to current staff, on top of their existing responsibilities, and many did not have prior experience in those roles or with MSN generally. Countries need to ensure there is appropriate staff and staff capacity in the government unit responsible for these functions (ie, in the anchorage unit). Second, there is a need for a mobile, national implementation team that can perform the cascading of MSN structures and capacities to subnational levels and provide much needed support to those levels over time, in line with the implementation science literature.64, 65, 66 Third, there is a need to effectively engage high‐level decision makers in government and partner organizations in addressing critical bottlenecks, through candid reporting from the anchorage unit, the use of real‐time progress markers, and the establishment of clear lines of accountability. Doing so will ensure that the limited time these decision makers can devote to MSN is used productively by enabling them to address bottlenecks that only they can address. The rationale for singling out these three actions is that all or most of the other challenges documented in this paper can be addressed if there are dedicated staff and clear procedures in place to do so. These staff also can become the focus for ongoing capacity strengthening and support in the areas of leadership, strategic management, boundary‐spanning work, M&E, strategic communications, and other vital functions.

Finally, there are many opportunities to gain further experience facilitating the work of CASs, by engaging with countries in the SUN movement or with other global health initiatives. Future work should recognize that boundary spanners as used in this project represent only one possibility, along with knowledge brokers, bridges, policy entrepreneurs, and technical support units14, 16, 57, 67; boundary spanning can have value at the level of leaders, managers, and frontline workers9, 68; and there are important questions about where BSAs should be employed and housed within or outside of the system.10, 62 In the present work, there were distinct advantages in having the BSAs attached to a university, as distinct from one of the vested stakeholder organizations, in relation to neutrality, trust, and the flexibility to interact with any and all of the MSN stakeholders. Upon reflection, some of the ambiguity and confusion concerning their role, contribution, and status in the system could be reduced by positioning them as knowledge brokers.69 This would be a natural and valued role for a university partner to play70 and would be a good entry point, recognizing that the staff may end up playing multiple roles in actual practice.15 For reasons of cost as well as capacity building, it is important to explore the potential for national universities to play such roles in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The African Nutrition Security Partnership was funded by the European Union through a grant to the UNICEF Regional Offices (WCARO and ESARO) which in turn funded and supported Cornell University for the work described in this paper. The authors are grateful for the financial support for this work as well as the commitment and collaboration of the many people and organizations working on multisectoral nutrition in these countries and in the regional offices.

APPENDIX A. CONDITIONS AND PRINCIPLES FOR EFFECTIVE GOVERNANCE

A.1.

| Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) Strategy and Roadmap 2016‐2020 (http://scalingupnutrition.org) | Health System Governance38 | Collective Impact39 | Collaborative Governance (Meta‐Framework) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Strategic objectives:

1. Enabling political environment, with strong leadership, multistakeholder platforms to align activities and take joint responsibility |

Strategic vision: leaders with a broad and long‐term perspective and strategic directions | Common agenda and shared vision for change, including common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving it through agreed‐upon actions | System context: resources, policy and legal frameworks, history with the issue, political dynamics, power relations, network connectedness, conflict/trust, diversity |

| 2. Follow best practice for scaling up proven interventions, including the adoption of effective laws and policies | Participation and consensus orientation: inclusion of diverse voices and interests towards the common good | Continuous communication to build trust and assure mutual objectives and common motivations | Drivers: leadership, incentives, interdependence, uncertainty |

| 3. Aligned actions with high‐quality and well‐costed country plans, with an agreed results framework, tracking, and mutual accountability | Rule of law: legal health frameworks, fairly and impartially enforced | Effective coordination, including dedicated staff with specific soft skills | Quality of engagement: discovering interests, problem framing, deliberation, decisions |

| 4. Increase resources, directed towards coherent, aligned approaches | Responsiveness: to the diverse needs of the population | Mutually reinforcing activities, coordinated via a mutually reinforcing plan of action | Shared motivation: trust, understanding, legitimacy, commitments |

| Engagement principles: transparent, inclusive, mutual accountability, consensus oriented, continuous communication, learning and adapting, cost‐effective, rights based | Accountability: government, private sector, and civil society are accountable to the public and institutional stakeholders | Shared measurement system, across all participants to ensure efforts remain aligned and participants hold each other accountable | Capacity for joint action: procedural/institutional arrangements, leadership, knowledge, resources |

| Intelligence and information to support informed decisions | Proximate outputs: improved policy, resources, staffing, management practices, monitoring, enforcement | ||

| Equity, inclusiveness, effectiveness, efficiency, ethics | System impacts: changes in aspects of the system context (above), collaboration dynamics and governance quality |

APPENDIX B. COUNTRY PROFILES (FROM GLOBAL NUTRITION REPORT 2014, 2015)

B.1.

| Burkina Faso | Mali | Ethiopia | Uganda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional status | ||||

| Stunting, % | 42 (2006) | 43 (2001) | 57 (2000) | 45 (2000) |

| 33 (2012) | 39 (2006) | 40 (2014) | 34 (2012) | |

| Wasting, % | 11 (2012) | 15 (2006) | 10 (2011) | 5 (2011) |

| Low birth weight, % | 14 (2010) | 18 (2010) | 20 (2005) | 12 (2011) |

| Poverty and population | ||||

| Gross domestic product per capita, US dollar | 1582 (2013) | 1589 (2013) | 1311 (2013) | 1365 (2013) |

| Poverty < $2/day, % | … | 79 (2010) | 66 (2011) | … |

| Population (millions) | 16.5 (2012) | 14.9 (2012) | 91.7 (2012) | 36.3 (2012) |

| Services and practices | ||||

| Antenatal care visits 4+, % | 34 (2010) | 45 (2010) | 19 (2011) | 48 (2011) |

| Breastfeeding (BF) initiation < 1 h, % | 42 (2010) | 57 (2010) | 52 (2011) | 53 (2011) |

| BF 12+ months, % | 96 (2010) | 90 (2010) | 96 (2011) | 87 (2011) |

| Exclusive BF 6 months, % | 25 (2010) | 20 (2010) | 52 (2011) | 63 (2011) |

| Severe acute malnutrition geographic coverage, % | 100 (2012) | 5 (2012) | 75 (2012) | 9 (2012) |

| Vitamin A full coverage, % | 99 (2012) | 93 (2012) | 31 (2012) | 70 (2012) |

| Oral rehydration salt for under 5s with diarrhea, % | 21 (2010) | 11 (2010) | 26 (2011) | 44 (2011) |

| DPT3, % | 90 (2012) | 74 (2012) | 61 (2012) | 78 (2012) |

| Iodized salt consumption, % | 34 (2006) | 74 (2006) | 20 (2006) | 87 (2006) |

| Minimum adequate diet, % | 3 (2010) | … | 4 (2011) | 6 (2011) |

| Minimum diet diversity, % | 6 (2010) | … | 5 (2011) | 13 (2011) |

| Gender equity | ||||

| Births to women <18 years, % | 28 (2010) | 46 (2006) | 22 (2011) | 33 (2011) |

| Female secondary enroll, % | 23 (2012) | 37 (2011) | 11 (2000) | 14 (2011) |

| Water and sanitation | ||||

| Improved water, % | 81 (2012) | 67 (2012) | 52 (2012) | 76 (2012) |

| Improved sanitation, % | 36 (2012) | 41 (2012) | 37 (2012) | 57 (2012) |

APPENDIX C. SEMISTRUCTURED INTERVIEW GUIDE

C.1.

Introduction to the Interviewee:

One of Cornell's objectives in this project is to help each of the four ANSP countries to move forward with their MSN approach. We are doing that by assisting and partnering with the government and other partners, as you have seen. Our other objective is to learn from experience in these four countries and share what we learn with other countries. Today's interview is intended to support both of these objectives.

Specifically, I want to talk with you about what it takes to build an effective and sustainable MSN approach. This is obviously a large and complex challenge and one that many countries are struggling with. As someone who has been very involved, I know you have a lot of insights about this. In addition to gathering your insights, I am hoping our discussion will help us both to reflect on the situation here in [country] and possibly identify some additional steps or strategies that could help us move the agenda forward. So this interview is about sharing and reflecting.

Is this clear? Is it ok to proceed?

| Question | Comments and Probes |

|---|---|

| Part 1: Your Thoughts Re the MSN Approach | |

| 1. To begin with, for the record can you tell me your current position and how you are involved with the MSN effort? | |

|

2. OK. Thank you. So I have noticed, as you may have as well, that not everyone has the same idea of what MSN is all about. To be sure we are on the same page, could you please tell me what it means to you? |

For the most part we simply want to take at face value whatever they offer, so specific probes are not used after their response. But if they give a very short and superficial answer you could ask them to say more about the purpose, design and intended functioning of MSN approach |

|

Thank you. 3. Now, I would like you to picture in your mind what the MSN system would look like a few years from now if it is fully developed and how it would be working. What would be in place, which institutions would be involved and what would be happening and how would it be improving nutritional status? |

As they respond, take brief notes of what they mention in relation to: ‐ what would be in place ‐ what would be happening ‐ which institutions would be involved These will be the basis for your follow‐up questions as follows: A. Thank you for painting that picture of a MSN approach. You mentioned A,B and C would be in place… is there anything else? (keep prompting until s/he has nothing else to offer). B. And you mentioned that D,E and F would be happening. Is there anything else that would need to be happening if the MSN approach is to be effective in improving nutrition? C. And you mentioned G, H, and I would be involved. Are there others? Which sectors do you think should be involved? If they do not mention sub‐national levels: D. And what about sub‐national levels: what needs to be in place, what needs to be happening and what institutions need to be involved? |

|

4. OK, great. Now that we have a picture of what needs to be in place and what needs to be happening, the question is: What conditions are necessary in order for this to be put into place and to function as intended? |

They may need some help understanding what we are getting at here. So you could give an example like this: “For instance, you mentioned there needs to be a strong coordination platform—well, what is needed in order to a platform to function in a strong way?” As they get rolling, you should prompt them to respond in relation to each of the items they mentioned in #3 above: Things in place—A, B, C, etc Things happening—D, E, F etc |

| 5. Wonderful. We are beginning to get a full picture of the approach and what it would take to be effective. Now I want us to focus on sustainability. If this whole MSN approach is to be sustainable—for 10 or 20 or more years—what will be needed? | They may have a lot of overlap here with their answers above (for effectiveness) because they may have been implicitly thinking in sustainability terms. But in some cases this question might also get them thinking differently about what needs to be in place and HOW things need to be done differently if MSN is to be sustainable. |

| Part 2: Your Reaction to the 12 Requirements for an Effective and Sustainable MSN | |

|