Abstract

Across Australia, prostate cancer support groups (PCSG) have emerged to fill a gap in psychosocial care for men and their families. However, an understanding of the triggers and influencers of the PCSG movement is absent. We interviewed 21 SG leaders (19 PC survivors, two partners), of whom six also attended a focus group, about motivations, experiences, past and future challenges in founding and leading PCSGs. Thematic analysis identified four global themes: illness experience; enacting a supportive response; forming a national collective and challenges. Leaders described men's feelings of isolation and neglect by the health system as the impetus for PCSGs to form and give/receive mutual help. Negotiating health care systems was an early challenge. National affiliation enabled leaders to build a united voice in the health system and establish a group identity and collective voice. Affiliation was supported by a symbiotic relationship with tensions between independence, affiliation and governance. Future challenges were group sustainability and inclusiveness. Study findings describe how a grassroots PCSG movement arose consistent with an embodied health movement perspective. Health care organisations who seek to leverage these community resources need to be cognisant of SG values and purpose if they are to negotiate effective partnerships that maximise mutual benefit.

Keywords: health advocacy, men's health, peer support, prostate cancer survivors

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer (PC) is the second most common male cancer and the world's fifth leading cause of cancer death in men (Ferlay, Soerjomataram, & Ervik, 2012). Historically, PC incidence has been driven by the availability of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing (Baade, Youlden, & Krnjacki, 2009), to date the only widely accessible method for the early detection of this cancer. The PSA test was first introduced into clinical practice in the United States (US) in the mid to late 1980s (Legler, Feuer, Potosky, Merrill, & Kramer, 1998) entering into Australian clinical settings in the early 1990s with use of the PSA test and PC incidence peaking in Australia in 1995 (Baade et al., 2009). However, the PSA test was mired in controversy. Inconclusive randomised controlled trial evidence regarding survival benefit from population screening has fuelled debate about the value of the early detection of this disease (Ilic, Neuberger, Djulbegovic, & Dahm, 2013). Despite this controversy, the 1990s saw the emergence of PC as a prominent, escalating health concern for men in their fifth and sixth decades, especially those residing in the developed world.

The rapid increase in PC incidence brought with it a heavy psychosocial and quality of life burden for survivors with little support available to meet their needs. Treatments for PC are associated with significant morbidity that includes heightened psychological distress, an increased risk of suicide and long‐term QoL concerns, especially for sexual well‐being (Bill‐Axelson et al., 2013; Chambers, Zajdlewicz, Youlden, Holland, & Dunn, 2014). While cancer support systems for Australian women with breast cancer were readily available by the 1990s such as the National Breast Cancer Foundation Australia (established 1994; National Breast Cancer Foundation, 2016), Breast Cancer Network Australia (established 1998; Breast Cancer Network Australia, 2016) and Breast Cancer Support Service and Young Women's Network in Queensland (Dunn, Steginga, Occhipinti, & Wilson, 1999; Steginga & Dunn, 2001), and Australian clinical practice guidelines for psychosocial care of women with breast cancer were published in 2000 (National Health and Medical Research Council, National Breast Cancer Centre, 2000), this was not the case for PC survivors. Additionally, again by comparison to women, men are low users of cancer support services and are less likely to discuss cancer‐related psychosocial concerns with their health professionals (Forsythe et al., 2013). Compounding this, the clinicians who treated these men were unlikely to refer their patients to support programs when they were available with the most common reason given as “men do not want to discuss their problems with others.” (Steginga et al., 2007) Thus, PC survivors were at risk of not seeking support; not being offered support and not finding support if they indeed did search for it.

In response, PC support groups began to emerge in Australia from the early to mid‐1990s. These were initiated and led in the main by PC survivors and/or their partners. As these groups became more numerous, affiliations began to form between the groups and they moved towards a national collective. In 1999, this led to the groups affiliating with the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia (PCFA) and in 2001 adopting the PCFA as their peak body (Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia, 2016). To date, research on PC support groups has applied a supportive care framework approach describing these groups primarily in their role of providing psychosocial support to PC survivors, applying social support theory and positing peer support as a unique model of helping based on shared mutual experience (Dunn, Steginga, Rosoman, & Millichap, 2003; Oliffe, Ogrodniczuk, Bottorff, Hislop, & Halpin, 2009; Steginga, Pinnock, Gardner, Gardiner, & Dunn, 2005). However, the motivations and experiences of PC survivors who formed these groups and whether formation of these groups might represent a grass roots health movement has not to date been described; a critical gap in knowledge when considering the scale of the PC burden in the community.

In this regard, it has been suggested that in the US, in contrast to breast cancer, a PC grassroots movement failed to develop owing to an unwillingness to act collectively or politically and PC survivors having a general tendency towards passive action (Kedrowski & Sarow, 2007). These authors argue that the PC movement as it exists was built top down rather than from the grass roots up. This has been contrasted to the breast cancer movement that in the 1970s was driven by a consumer led demand for increased research, improved treatments and early detection, developing over time to a demand for better survivorship care (Kedrowski & Sarow, 2007). To date, a narrative about how and why PC survivors organised themselves at a grassroots level is largely absent.

Accordingly, we undertook a qualitative investigation with the aim of exploring the motivations for action of PC survivors who instigated the PC support group movement in Australia, their experiences in forming groups in their local areas and connecting with other PC support groups on a state and national level, and their perspectives on past and future challenges in leading PC support groups and the broader movement.

2. Method

2.1. Study approach

The approach undertaken in the current study was consistent with strategies described in grounded theory methodology (e.g., Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Specifically, our approach was inductive; involved a constant comparative method of analysis which led to additional focus group data collection and analysis; and conceptualisation of study questions and analysis occurred without a preconceived theory in mind. However, it should be noted that we did not follow the particular nuances and guide outlined by proponents of this approach for data analysis. Instead, the guidelines for thematic analysis outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006) were adopted for data analysis, which has many similarities to a grounded theory analysis approach. Our frame as social and behavioural scientists was interpretivist and aimed at understanding the lived experience of a target sample of individuals who led PC support groups.

2.2. Participants and recruitment

2.2.1. Interviews

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Griffith University Human Research Ethics Committee. Survivors and/or their partners who led the early development of Australian PC support groups (referred to as support group leaders) were identified via the existing consumer networks of the investigator group and the support group leader network and invited to participate. Purposive sampling was undertaken to ensure that PC support group leaders from New South Wales where the movement began and support group leaders from each Australian state and territory were represented, and that groups with a unique focus (e.g., an action support group focused on advocacy more than support) or mode of delivery (e.g., an online support group) at the time were also captured. Of 25 support group leaders identified, two support group leaders did not respond to the invitation and two declined an interview because they were unwell (including the participant representing the Australian Capital Territory).

Of the 21 participating PC support group leaders (84% response rate), 19 were PC survivors and two were partners of PC survivors. Support group leaders represented New South Wales (n = 9), Victoria (n = 1), South Australia (n = 2), Northern Territory (n = 1), Queensland (n = 4), Western Australia (n = 1), Tasmania (n = 2) and nationally (n = 1). Participants were on average 76.4 years of age (SD = 5.8; range 67–87) with most born in Australia (71.4%), married (85.7%), highly educated (47.6% university/college degree; 19.0% trade/technical certificate or diploma) and retired from the workforce (81.0%). Men had been diagnosed with PC between 5 and 21 years prior to the study (M = 16.1; SD = 4.9) and were on average 60.8 years (SD = 5.6) at the time of diagnosis. Men were treated with radical prostatectomy (73.7%), radiation therapy (42.1%) and/or hormone therapy (31.6%) (some men received more than one treatment type). Most participants became involved in a support group between the years 1994 and 2000 (81.8%) (mode = 1996; range 1994–2009). Support groups that these participants were currently involved in had been operating on average for 16.5 years (SD = 3.6; range 5–21) and had between 12 and 1,000 members (M = 237.3; SD = 357.9); with most groups delivered face to face (90.9%) and peer‐led (86.4%).

2.2.2. Focus group

Fourteen of the interview participants (all PC survivors) were later approached to participate in a focus group, again applying purposive sampling to ensure leaders who were involved in the earliest known PC support groups were included and as far as practical ensure representation across states. PC survivors had become involved in support groups between the years 1996 and 2001, with 1997 as the median year of involvement. Participants who declined were either too unwell (n = 4) or had competing commitments (n = 4). Six PC support group leaders attended the focus group.

2.3. Study procedure

A member of the research team contacted PC support group leaders for a one‐hour semi‐structured telephone interview. Interviews were conducted by two experienced interviewers with a background in behavioural science. Interviews occurred from November 2014 to March 2015, and were between 33 and 122 min in length. All participants provided written informed consent. The interview began with a broad orientating question regarding motivations for starting a support group and group development, followed by questions about awareness of and connections with other support groups and the broader movement, actual challenges experienced and anticipated future challenges. Interviews were audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim.

A focus group was then held in a face‐to‐face setting (June 2015) with six PC support group leaders who had participated in the interviews to further explore in a group setting their personal reflections about their motivations, experiences and challenges experienced in establishing PC support groups and the broader networks. The focus group was led by two highly experienced facilitators with a background in social and behavioural sciences and supportive cancer care. The focus group process was unstructured with lead questions about the formation of groups, networking and challenges associated with forming support groups and the lessons learned. The process allowed for men to both challenge and support ideas put forward by other group members as they emerged. The process also served as an opportunity for member‐checking of researcher interpretation of the data. The focus group was audio‐recorded and transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data analysis

Interview and focus group transcripts were analysed using thematic analysis given that the aim was to describe a phenomenon with few, if any, prior studies (Attride‐Stirling, 2001; Braun & Clarke, 2006). Coding of transcripts occurred iteratively upon completion of data collection and involved constant comparison between codes generated and the data. Initially, two authors (M.H., M.C.) independently analysed a sub‐set of the transcripts using an inductive approach in which codes emerged from the data with the purpose of generating a preliminary coding scheme. A third author further developed the coding scheme after independent review of all transcripts (S.C.). Consensus on the final coding scheme was achieved with involvement of a fourth author (J.D.). In‐text examples were identified across transcripts and documented to illustrate and verify the labelling of each theme. Coders had social and behavioural sciences backgrounds. In order to fully understand the motivations, experiences and challenges of PC support group leaders as part of a grassroots movement, and to situate the results of this study within a broader community and health context, we also consider potential synergies with an embodied health movement (EHM) perspective (see Discussion).

3. Results

Across the interview and focus group data, four global themes were identified: the illness experience; enacting a supportive response; forming a national collective and future challenges. Global themes were interlinked, each influencing the other with consistency across interview and focus group data. Exemplar quotes for themes are presented below.

3.1. The illness experience

The global theme illness experiences included three sub‐themes: isolation and neglect; anger and betrayal; and stigma.

3.1.1. Isolation and neglect

Prostate cancer support group leaders described experiencing isolation and neglect in the illness experience. Many of these men were diagnosed with PC in the mid‐1990s at which time there were no PC specific cancer control or support agencies and advice for PC survivors and their partners about treatment effects and management strategies for these was sparse or absent. As support group leaders explained:

When I was operated on, there was nowhere to go for assistance or help, or understanding; you just had to somehow soldier on. (Interview, Participant 23)

I was actually diagnosed in 1996 and weathered it by myself for some time. In fact, I rarely spoke to another male in all that time, no‐one put their hand up to say they were going through it, and I found no‐one. I said there must be one other person there who I can share the load with and maybe gain some other insights. (Interview, Participant 14)

As well, PC survivors and partners reported feeling unable to discuss PC in their usual social network and from this developed a sense of isolation in facing PC alone.

I still have men – take one of my really good mates. He was diagnosed, he was treated, he was left incontinent and was angry and he never told a soul until his wife came to me one day, said, “I didn't know”, one of my best mates, he said he wasn't going to tell anyone. (Interview, Participant 14)

This sense of isolation was compounded by the perception that health professionals were not focussed on psychosocial support for men facing PC.

It was very hard to get started in the movement because nobody knew us, nobody wanted to know us, the GPs, general practitioners, and urologists did not want to know us because we were a group that had come up from actually nowhere and nobody else was interested in prostate cancer. (Interview, Participant 19)

3.1.2. Anger and betrayal

Support group leaders described conflict in the public domain about PSA testing for the early detection of PC and feelings of anger at what they perceived to be neglect of men both at a government and health system level, as well as by health care providers.

And so, the big problem was when public speakers came out of some note denigrating PSA tests … the government says, “Oh well, okay, we won't subsidise men's health because they don't really have a test and it's an old man's complaint and they won't last very long anyhow.” They didn't speak that publically but that was the impression. (Interview, Participant 4)

This included the perception that as older men their lives were not highly valued and that men were being diagnosed with late stage cancer due to health professionals’ negative attitudes to screening for PC.

We had a number of men … depressed about the fact that they had been diagnosed with prostate cancer too late and they had no knowledge of the disease and most of them said if they had have known how prevalent it was in the community, they would have gone off and had tests and hopefully would have been diagnosed at a time when they could have been cured, but these men were all basically too late and incurable … there wasn't enough awareness around prostate cancer. (Interview, Participant 16)

3.1.3. Stigma

The sub‐theme of stigma about having PC was also described and it was felt this was more pronounced in country or regional areas and small towns. Stigma was seen as leading to social isolation as well as fear of discrimination.

Well talking about stigmas, when I first was diagnosed, it was you heard stories how – and particularly in rural where people, ah, would say, um, you know, they'd be walking down the street and someone they knew would come down the other way and they'd cross the other side of the street and wouldn't speak in case they might catch it. (Focus group, Participant 3)

I remember talking to a chap… and he said, “I wouldn't want anyone knowing I had prostate cancer.” I said, “Well, why not?” He said, “Well, look, I run a bit of a business here.” He said, If they think that I've got prostate cancer and I won't be around much longer, they'll go somewhere else.” (Interview, Participant 14)

3.2. Enacting a supportive response

Four sub‐themes were identified within the global theme of enacting a supportive response. These sub‐themes were like minds coming together; negotiating health systems; learning by experience and women as fellow travellers.

3.2.1. Like minds coming together

Support group leaders described the process of forming groups as ‘like’ minds and experiences coming together to address the lack of support and isolation that men were experiencing.

The doctors didn't give you anything to speak of and there was nothing, relatively little in the libraries, and of course PCFA wasn't up and running. So you just had to find out yourself. So the best way was to talk to others. (Interview, Participant 13)

Well, it became very obvious through some members of my family who had been involved in support groups, I hadn't up to that stage, just how much benefit you could get out of being with a group of similarly affected, like‐minded people, rather than trying to carry the lot on your own. And the difference between seeing those people and knowing those people and knowing people who insisted on doing it on their own was pretty stark quite often, so it certainly seemed to me to be pretty obvious that there was good value in having a support group. (Interview, Participant 9)

This included identified champions who took a lead role in initiating groups, men from different social backgrounds coming together and in some groups the female partners of these men taking leadership or support roles in the groups.

There'd been a fellow who was sort of you know a bit around the traps, a delightfully vague term, who'd been like a missionary and running around the country starting support groups and he's a bloke who had prostate cancer. (Participant, 9)

My own group as an example, we had ladies with us from the very beginning. They were making sandwiches, they were there to support us … I think the important thing that I see here is that they have a vital role to play at the beginning of our support group. They were there with us right from the word go and I think with their support, we did things a lot better than we would have done if we were floundering along by ourselves. (Focus group, Participant 2)

Groups were sometimes developed in an informal partnership with health professionals while others were independent of health care providers. For example:

Well, bearing in mind I'd just been diagnosed with prostate cancer there was very little information about it, so we – and working with a urologist we realised that there are other people in the same area and we wanted to make it easier for others that were going through the same thing. So that's how we started to loosely connect and then we all came together. (Participant 12)

Leaders also described developing management strategies for organising their support groups. For example:

So we organised a committee, we organised roles, we outlined roles, we organised a constitution, we organised a meeting place which was the local shire building, because we could get that for nothing through a friend. (Interview, Participant 11)

3.2.2. Negotiating health systems

In the focus group, support group leaders expanded on the sub‐theme about negotiating the medical health system in the early formation of support groups with credibility and influence as key issues. This relationship changed over time. Specifically, when support groups were first forming many medical clinicians were largely dismissive of their activities and were reluctant to be involved with group activities or refer patients to groups. For example:

The medical profession had to back up against the walls and we wanted to bloody make a difference. They couldn't fight us no matter what they thought, you know. We had a need, a very strong need. The community saw it and they couldn't beat us. They had to do it one way or another because we were going to get stronger and stronger and we were going to change them. (Focus group, Participant 2)

Over time however this changed to a position of clinicians seeking to attend groups and be represented or profiled in group newsletters.

Isn't it interesting though that over time the relationship changed from one where you (support groups) had no credibility (with health professionals) to one where they were trying to attach themselves (to us) to gain credibility. (Focus group, Participant 1)

3.2.3. Learning by experience

A sub‐theme of learning by experience in work of running support groups was also described.

(At) the very beginning, we didn't have a blue print. There was no plan. There was no – nobody could tell us really what we should be doing but we just had a fundamental belief that we knew what we were doing, we simply wanted to help a fellow man who'd been diagnosed with the disease. That's all we wanted to do. We wanted to try and help other people. (Focus group, Participant 2)

We just followed our heart basically; that's what we did. We – we – we really felt that, you know, what we wanted to do was help people and that's putting it very simplistically. (Focus group, Participant 2)

3.2.4. Women as fellow travellers

A sub‐theme about support from women was also discussed with men describing their female partners as being fellow travellers in the support group movement providing practical, emotional and strategic support.

At the first meeting, national meeting of support groups at Darling Harbour, one third of the people that attended that were women. Were – were ladies, were wives and partners. Now those ladies were involved in everything that happened. They went to the workshops with us, they discussed the strategies, they argued, they stood up for us. (Focus group, Participant 2)

Every time we went to try and set up a support group, there would be three or four guys and three or four women, partners with us. And the amount of women that came to these, ah, medical talks or, ah, awareness evenings, when they saw the women with the guys, that – that sold a lot of support groups. That started a lot of support groups. So I just take it for granted women are always – they've always been there and they're always going to be there. (Focus group, Participant 5)

3.3. Forming a national collective

Within the global theme of forming a national collective four sub‐themes emerged: sharing common experiences and learning from each other; having a united and powerful voice; symbiosis and interdependence; and self‐determination and identity.

3.3.1. Sharing common experiences and learning from each other

Support group leaders described seeking common experiences and learning from and supporting each other in running support groups. Within this was the purpose to establish common practices and build sustainability. For example:

We felt that support groups ought to get together so that they can compare notes on how they operated because, in the early days, everybody operated differently. A lot was the same but you needed to get together with other people to find out the problems that they may have encountered, the difficulties sometimes in getting good guest speakers. (Interview, Participant 6)

Linkages between groups across both states and the country more broadly were seen as a way to build sustainability into the group movement.

I could just see no future in isolated little cells who almost inevitably would have a short life and a merry one and then just fade away. (Interview, Participant 9)

So that was the beginning of the national support group movement, that was July 2001. Now once that happened of course there was, if you like, I guess an official recognition that we were altogether and we were all working in the one direction and there was much more communication between groups through the PCFA. (Interview, Participant 16)

There was however acknowledgement that at different times there was tension arising from competing interests in forming a national movement.

Not everyone threw their lot in with him (early champion) but there were a number of people that did and he'd always say, “You know, will you join me? Will you join me?” I said, “Well, you know, what's the 5‐year plan, you know? What's going?” ‐ you could never give up. And he'd always say, “You know, I got this bloke and this group with me and this group with me.” And at one stage, (various organisations) were claiming to have the same groups as part of them. (Interview, Participant 14)

3.3.2. United and powerful voice

The importance of a united and common voice to improve care for PC survivors was expressed.

We came together as one; Unity is strength; We were looking for a national voice. (Focus group, Participants 2 and 4)

You're not going to get anywhere if you don't have power. You need to have large memberships: you need to have a lot of support across a wide area and so on. If you can't demonstrate these things, then you're not going to really be taken much notice of. (Interview, Participant 15)

Participants described a process of group leaders, health professionals and the PCFA negotiating how to work together. Within this was the acknowledgement that while they all shared a common purpose in supporting men, perspectives on how to achieve this differed at times. For example:

And (new health professional) was more hospital‐orientated. I don't know, she ran it differently to (previous coordinator) and she sort of held the reins more on each support group, which I thought was – which – she did a real good job but I don't think that it ran as well as when (previous coordinator) had loose reins on it and we tend to do our thing and she sort of would steer us. Well, loose reins, let's say in our particular instance, let the guys do their thing, tell me what they want, I'll assist them. If I see that they're going off the rails a little bit, I'll sort of steer them back in. Tight reins mean that you run it as you see it. … The only difference and it got a couple of blokes’ nose out joint but there wasn't a guy out the front spruiking. But, look, it went well. … except that, when the guys were doing it, we could hang around in the meeting room ‘til half‐past 9.00 or 10 o'clock. Whereas, like, these are paid people and so as soon as the meeting was finished it was very brusque, there wasn't much time for discussion. Our main form of support was before and after the meeting and it was very, very informal. That didn't happen under a tight rein system. (Interview, Participant 14)

3.3.3. Symbiosis and interdependence

In discussing the process of integrating with the PCFA, a sub‐theme of symbiosis and interdependence emerged. In this symbiotic relationship, the groups and the PCFA were seen as separate and having their own focus and goals but also clearly entwined. On this point, there was a divergence of views about the extent to which PCFA and the groups were a single collective or two distinct but linked entities.

I just see PCFA and the support groups as one, I don't – I – I can't – I can't chip them apart. I see ourselves being the soul of PCFA. (Focus group, Participant 3)

But I mean we are two different people, you know. I mean people at longer support groups are caring people, you know and care. As I see the PCFA, they are more focused on raising money maybe and I mean they have got jobs. So there is a certain degree of ambition there, getting things done. I mean they are – they are two different personalities. (Focus group, Participant 1)

3.3.4. Self‐determination and identity

Support group leaders also raised the issue of identity and potential for a loss of the support group story within the corporate history.

I thought this is all out of whack, you know, here we should be promoting men making decisions about their health which we've been renowned as not doing and in fact here we have a group of people all out of Australia making – making this contribution and that should be the highlight not necessarily because it should be done but also because it was done and by a lot of people, not just this group or that group but everybody. (Focus group, Participant 4)

3.4. Future challenges

Within the global theme future challenges, two key sub‐themes were described by support group leaders: sustainability and the need to be inclusive.

3.4.1. Sustainability

Challenges in group sustainability revolved around the need for leadership succession planning and for new members to take up executive roles in managing the group, as well as practical support (e.g., venues to meet).

So it's getting that infrastructure, and as often as they said, you have to try and find somebody that's going to take over your group for you, finding someone that's younger than you that is interested to take it over is another thing. (Interview, Participant 13)

Most people only come to get their own needs satisfied. And I'm not being critical when I say that but it does not help the group because they come for one, two, three, four meetings and then drop off except for being on the mailing list. And less than 10% of people who come to group are at all interested in doing anything to help the group to stay alive and to function properly. Really, it is very difficult and I do not believe there is a group in Australia that does not have succession problems. So few people are prepared to hop in and roll up their sleeves and do a job. That is the biggest problem we face, I think. (Interview, Participant 9)

The emotional burden for group leaders of losing group members to PC was also described.

So yeah, look you don't take the leadership of a prostate support group on lightly because there's a very major time commitment required and I do think also there's an emotional aspect involved as well. We've lost three of our longer term members in the past year and we do understand that life happens that way and we all go into the group knowing that those with advanced disease will one day not be with us. Their time will come when I won't be with them either. So it is life but nevertheless when you know a large number of people that are in this category and you start to lose them in numbers then that can be an emotional impact on you as well. (Interview, Participant 16)

3.4.2. Inclusiveness

Leaders described the need for support groups to be inclusive of men and family members from diverse backgrounds and with differing needs. This included the partners of PC survivors, men of non‐heterosexual orientations, younger men, men at different illness stages and people from diverse cultural backgrounds. For instance:

So I think it's how to reach your community, how to be inclusive of your gaze, of non‐English speaking, I mean, there are not many around here, but we had one African bloke recently who came, and younger men are always an issue. (Interview, Participant 11)

We've got five or six, there might even be more than that now, support groups for gay and bisexual men, just the difference of their requirements to what it is for heterosexual men. (Interview, Participant 13)

As well, finding ways to reach out to men who typically may not attend a support group was described as a challenge.

And the other thing is we've got to attract people to support groups, but then there's another point that not everyone wants to go to a support group, like, there's high powered business people that wouldn't fit necessarily comfortably in a support group setting – they've got to be connected to the network by way of receiving a newsletter, by way of telephone counselling, whatever. So they're the challenges that we face today that are – we're working on in the various areas, so it's not – a support group network is not turning up to a support group every second week or every month necessarily. It's being connected to PCFA by a network in whatever form. (Interview, Participant 12)

4. Discussion

The current study describes the motivations and experiences of Australian PC survivors and their partners in forming community‐based support groups locally, and then connecting nationally, responding to a lack of men‐centred psychosocial oncology care. In brief, PCSGs formed as an individual and collective reaction to a cancer experience that was for many an isolating and traumatic life event. While this reaction focussed initially on mutual support, advocacy for the improvement of care for men with PC and their families also emerged in an interconnected dynamic. From a broader theoretical perspective, results of this study describe a prevailing grass roots and consumer activism response to PC that is consistent with an EHM framework.

Embodied health movements have been defined as organised movements that challenge science (and medical practices) from all stages of the disease from the illness experience perspective (Brown et al., 2004). Brown et al. (2004) and others propose that EHMs have three characteristics: (1) accessing the embodied experience of people with the disease; (2) challenging medical science or health practices or services and (3) collaborating with scientists and health care providers to pursue change (Zavestoski et al., 2004). In the 1990s, the health care systems largely failed to address the psychosocial needs of PC survivors and to the consequences of the widespread use of PSA testing and subsequent increase in PC incidence. Ironically, the dominant epidemiological paradigm at the time was that PC was a disease best undetected because most men would die with their disease and not of it (Brown et al., 2001). This longstanding belief framed the health care system disease focus but failed to take into account the increasing life expectancy of men and the impact of mixed messages about the virtues of PSA testing. As a consequence, many PC survivors took on activist roles working both outside of and within traditional health services to provide much needed support for men and their families, and to challenge the health system to hear their collective voice towards lobbying support to improve PC services. In this role, men worked across traditional lay‐professional boundaries, a characteristic of EHMs (Zavestoski et al., 2004), to advance their health and the health of other men experiencing PC.

Building on this finding, it seems that the early indiscriminate PSA testing drove debate round the science of PC disease amid fuelling unprecedented health advocacy from the ever increasing number of men experiencing the illness (and its treatments side effects). The 1990s emergence of PSA testing also occurred when the Internet was not widely subscribed to as a health information resource and home use of the internet by older men was uncommon (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1996). This likely heightened isolation around PC in that period. Taken together, and consistent with an EHM framework, it can be reasonably argued that PC support groups emerged alongside the PSA to attend to the psychosocial needs of the increasing number of men experiencing PC and their families. The impressive prevailing nature of the groups however affirms the ongoing need for such services, and is testament to the resilience of advocates who continue to work to advance the health of PC survivors and their families.

Underpinning the demand for PC support groups is a range of prevailing historical factors. Specifically, at the point of diagnosis many men experience isolation and neglect with regard to their psychosocial needs. In addition, the PSA testing controversy continues and central to the advocacy work of PC support groups is raising public awareness about the availability of and need to understand PSA testing. It was, and perhaps still is, grievances around the PSA that galvanised men to move forward, not only to local action in providing a support to other men, but to muster their national collective voice to influence health services and research. The coalition and then affiliation with the PCFA served the dual purpose of aiding men in their local support function through shared learning and practical support, and also provided a mechanism for advocacy on a broader national scale. Hence, the partnership between the affiliated support groups and the PCFA was, and is crucial, to facilitating the national support group coalition. Further, the development of these two key national groups (i.e., the Association of Prostate Cancer Support Groups and the PCFA) at a similar point in history with their shared goals aided the development of a symbiotic relationship. Specifically, both groups were responding to national uncertainty about PC control with the group alliance increasing the power and strength of both. This finding highlights the role of historical context and timing as key influencers in how a local community support response can develop into an EHM.

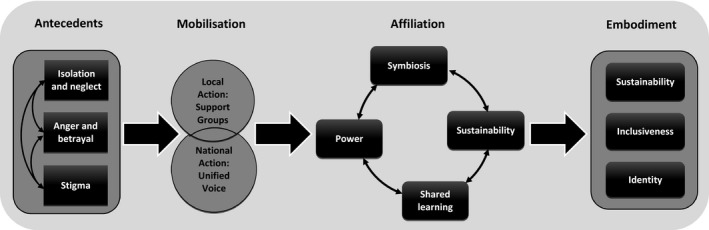

In synthesising the results of the current study and an EHM perspective, Figure 1 outlines a proposed model detailing a process where the antecedents of isolation and neglect, anger and betrayal and stigma lead to mobilisation on a local and national level; and where affiliation with an organised group acts to increase power and influence within a symbiotic relationship to support sustainability. From this, embodiment as the next phase of development of the collective identity emerges alongside the need for flexibility to support sustainability and inclusiveness to emerging needs.

Figure 1.

Process of mobilisation of prostate cancer survivors towards a supportive action network

As a case study of a grassroots, health movement led by men these findings extend our conceptual understanding of the conditions under which EHMs may emerge. It has been proposed that social groups that do not have a clear link to social movement or a history of previous injustices (for example on the basis of race or gender) will find it difficult to mobilise (Brown et al., 2004). Hence, breast cancer advocacy groups are frequently described as case studies for EHMs with linkages to the women's health movement and the injustices experienced by women cited as key potentiating factors. It has also been proposed that a grass roots PC movement (in the US) failed to galvanise due to men's reluctance to discuss their disease openly, and that PC survivors lacked an empowered educated base (Kedrowski & Sarow, 2007). The current study findings and the work of Canadian researchers (Oliffe, Gerbrandt, Bottorff, & Hislop, 2010; Oliffe et al., 2007, 2011) do not support this contention. Australian PC survivors and their partners began organising at the grass roots level, across classes, well before the formation of an institutional response to the needs of PC survivors and were agent in presenting their illness experiences to health services and researchers as a powerful and influential epistemology. If this grass roots movement is specific to the Australian context, then perhaps this links to values about mateship (an Australian cultural idiom of equality, friendship and solidarity that implies a willingness to act for others) that is frequently described as part of the Australian national identity, particularly for men in the context of adversity and war (Oliffe, 2009). In addition, it may also link to masculinity, support and advocacy work between men who share the experience and context of PC may connect to masculine beliefs about self‐reliance and taking action (Chambers et al., 2016). Future research to investigate PC movements in other locales would help to elucidate the role of culture, class and gender in EHMs.

These findings have implications for health services that seek to provide peer support for people with cancer. The numerous studies and reviews to date on peer support typically apply a traditional health services model and clinical evidence‐based empiricism to describe and evaluate peer support programs (Campbell, Phaneuf, & Deane, 2004; Hoey, Ieropoli, White, & Jefford, 2008; Macvean, White, & Sanson‐Fisher, 2008); and from this prescriptions of how peer support group leaders should be developed, trained and managed by institutions are derived (Zordan et al., 2012). These approaches generally fail to consider peer support linkages to a social movement but rather apply their own paradigm (the dominant psycho‐oncology paradigm) about what cancer support is and should be. To date, this appears to represent a disconnect between psychosocial care and the social context of illness; and how survivors can respond collectively and organically to the adversity a diagnosis of PC presents. In brief, the PC support group movement provides an example of the agency and resilience of both individuals and communities in responding to the threats of cancer (Campbell & Burgess, 2012). Applying a traditional health services paradigm to peer support has power and resource implications where professional care providers lead, oversee and act as quality controllers for peer support. In such partnerships ,mutuality is rare (Aveling & Jovchelovitch, 2014) and this raises the potential for conflict to arise about who allocates and directs resources, as well as how support is enacted. As a final point, cancer activism over time can be expected to evolve in response to the context in which it is situated. These contextual influences include developments in medical technologies and health services, advancements in communication methods, and potentially other broader social, economic and legislative changes. Disruptive episodes provide potential leverage points for cancer activism, with the internet and social media as one example where cancer consumers have been able to democratise knowledge about medical treatments and connect rapidly and efficiently to advocate for change. In this process, health services themselves will also need to adapt, and hopefully become more agile in response to consumer demand.

In conclusion, the current study shows how a grassroots health movement can flourish and grow and lead to social change. Ideally, partnerships between community groups and relevant institutions will allow for symbiosis while still supporting the collective identity of the groups and their unique and often unstructured approaches to support and activism. Developing and sustaining these partnerships is a priority for health services, community‐based peer support groups, as well as researchers who seek to describe and develop peer support and community responses to advance the health and well‐being of PC survivors and their families.

Acknowledgements

SKC is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship. This project was supported by the Prostate Cancer Support Groups of the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia. We thank Melissa Legg for research assistance and Leah Zajdlewicz for project support. Finally, we acknowledge the contribution of the bannermen and leaders of the prostate cancer support group movement in Australia and globally.

Dunn J, Casey C, Sandoe D, et al. Advocacy, support and survivorship in prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27:e12644 https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12644

References

- Attride‐Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (1996). Household use of information technology, Australia. Cat. no. 8146.0. Canberra: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Aveling, E.‐L. , & Jovchelovitch, S. (2014). Partnerships as knowledge encounters: A psychosocial theory of partnerships for health and community development. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(1), 34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baade, P. D. , Youlden, D. R. , & Krnjacki, L. J. (2009). International epidemiology of prostate cancer: Geographical distribution and secular trends. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 53(2), 171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bill‐Axelson, A. , Garmo, H. , Holmberg, L. , Johansson, J.‐E. , Adami, H.‐O. , Steineck, G. , & Rider, J. R. (2013). Long‐term distress after radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in prostate cancer: A longitudinal study from the Scandinavian prostate cancer group‐4 randomized clinical trial. European Urology, 64(6), 920–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Breast Cancer Network Australia (2016). Our history. Available from: https://www.bcna.org.au/about-us/our-history/ [last accessed 24 September 2016].

- Brown, P. , Zavestoski, S. , McCormick, S. , Linder, M. , Mandelbaum, J. , & Luebke, T. (2001). A gulf of difference: Disputes over gulf war‐related illnesses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(3), 235–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, P. , Zavestoski, S. , McCormick, S. , Mayer, B. , Morello‐Frosch, R. , & Gasior Altman, R. (2004). Embodied health movements: New approaches to social movements in health. Sociology of Health & Illness, 26(1), 50–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. , & Burgess, R. (2012). The role of communities in advancing the goals of the Movement for Global Mental Health. Transcultural Psychiatry, 49(3–4), 379–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, H. S. , Phaneuf, M. R. , & Deane, K. (2004). Cancer peer support programs—do they work? Patient Education and Counseling, 55(1), 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. K. , Hyde, M. K. , Zajdlewicz, L. , Lowe, A. , Wootten, A. , Oliffe, J. , & Dunn, J. (2016). Measuring masculinity in the context of chronic disease. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 17(3), 228–242. doi:10.1037/men0000018 [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, S. K. , Zajdlewicz, L. , Youlden, D. R. , Holland, J. C. , & Dunn, J. (2014). The validity of the distress thermometer in prostate cancer populations. Psycho‐Oncology, 23(2), 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J. , Steginga, S. K. , Occhipinti, S. , & Wilson, K. (1999). Evaluation of a peer support program for women with breast cancer—lessons for practitioners. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 9(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, J. , Steginga, S. K. , Rosoman, N. , & Millichap, D. (2003). A review of peer support in the context of cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 21(2), 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlay, J. , Soerjomataram, I. , & Ervik, M . (2012). GLOBOCAN 2012 v1. 0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No. 10 [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe, L. P. , Kent, E. E. , Weaver, K. E. , Buchanan, N. , Hawkins, N. A. , Rodriguez, J. L. , & Rowland, J. H. (2013). Receipt of psychosocial care among cancer survivors in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31(16), 1961–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoey, L. M. , Ieropoli, S. C. , White, V. M. , & Jefford, M. (2008). Systematic review of peer‐support programs for people with cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 70(3), 315–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, D. , Neuberger, M. M. , Djulbegovic, M. , & Dahm, P . (2013). Screening for prostate cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD004720. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004720.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedrowski, K. M. , & Sarow, M. S. (2007). Cancer activism: Gender, media, and public policy. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Legler, J. M. , Feuer, E. J. , Potosky, A. L. , Merrill, R. M. , & Kramer, B. S. (1998). The role of prostate‐specific antigen (PSA) testing patterns in the recent prostate cancer incidence decline in the United States. Cancer Causes and Control, 9(5), 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macvean, M. L. , White, V. M. , & Sanson‐Fisher, R. (2008). One‐to‐one volunteer support programs for people with cancer: A review of the literature. Patient Education and Counseling, 70(1), 10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Breast Cancer Foundation (2016). Milestones. Available from: http://nbcf.org.au/about-national-breast-cancer-foundation/about-us/milestones/ [last accessed 24 September 2016].

- National Health and Medical Research Council, National Breast Cancer Centre (2000). Psychosocial clinical practice guidelines: Providing information support and counselling for women with breast cancer. Available from: https://canceraustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/pcg-psychosocial-clinical-practice-guidelines_504af02627f10.pdf [last accessed 24 September 2016].

- Oliffe, J. (2009). Health behaviors, prostate cancer, and masculinities a life course perspective. Men and Masculinities, 11(3), 346–366. [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe, J. L. , Bottorff, J. L. , McKenzie, M. M. , Hislop, T. G. , Gerbrandt, J. S. , & Oglov, V. (2011). Prostate cancer support groups, health literacy and consumerism: Are community‐based volunteers re‐defining older men's health? Health, 15(6), 555–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe, J. L. , Gerbrandt, J. S. , Bottorff, J. L. , & Hislop, T. G. (2010). Health promotion and illness demotion at prostate cancer support groups. Health Promotion Practice, 11(4), 562–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe, J. L. , Halpin, M. , Bottorff, J. L. , Hislop, T. G. , McKenzie, M. , & Mroz, L. (2007). How prostate cancer support groups do and do not survive: British Columbian perspectives. American Journal of Men's Health, 2(2), 143–155. doi:10.1177/1557988307304147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliffe, J. L. , Ogrodniczuk, J. , Bottorff, J. L. , Hislop, T. G. , & Halpin, M. (2009). Connecting humor, health, and masculinities at prostate cancer support groups. Psycho‐Oncology, 18(9), 916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia (2016). Mates helping mates: A history of prostate cancer support groups in Australia. St Leonards, NSW: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Steginga, S. K. , & Dunn, J. (2001). The young women's network: A case study in community development. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 11(5), 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Steginga, S. K. , Pinnock, C. , Gardner, M. , Gardiner, R. , & Dunn, J. (2005). Evaluating peer support for prostate cancer: The Prostate Cancer Peer Support Inventory. BJU International, 95(1), 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steginga, S. K. , Smith, D. P. , Pinnock, C. , Metcalfe, R. , Gardiner, R. A. , & Dunn, J. (2007). Clinicians’ attitudes to prostate cancer peer‐support groups. BJU International, 99(1), 68–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A. , & Corbin, J . (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Zavestoski, S. , Morello‐Frosch, R. , Brown, P. , Mayer, B. , McCormick, S. , & Altman, R. G. (2004). Embodied health movements and challenges to the dominant epidemiological paradigm. Research in Social Movements, Conflict and Change, 25, 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Zordan, R. D. , Butow, P. N. , Kirsten, L. , Juraskova, I. , O'Reilly, A. , Friedsam, J. , & Hobbs, K. (2012). The development of novel interventions to assist the leaders of cancer support groups. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(3), 445–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]