Abstract

Background

The transition from child to adult health care is a particular challenge for young people with cerebral palsy, who have a range of needs. The measurement of reported needs, and in particular unmet needs, is one means to assess the effectiveness of services.

Methods

We recruited 106 young people with cerebral palsy, before transfer from child services, along with their parents to a 3‐year longitudinal study. Reported needs were measured with an 11‐item questionnaire covering speech, mobility, positioning, equipment, pain, epilepsy, weight, control of movement, bone or joint problems, curvature of the back, and eyesight. Categorical principal component analysis was used to create factor scores for bivariate and regression analyses.

Results

A high level of reported needs was identified particularly for control of movement, mobility, and equipment, but these areas were generally being addressed by services. The highest areas of unmet needs were for management of pain, bone or joint problems, and speech. Analysis of unmet needs yielded two factor scores, daily living health care and medical care. Unmet needs in daily living health care were related to severity of motor impairment and to attending nonspecialist education. Unmet needs tended to increase over time but were not significantly (p > .05) related to whether the young person had transferred from child services.

Conclusions

Reporting of unmet needs can indicate where service development is required, and we have shown that the approach to measurement can be improved. As the number of unmet health needs at the start of transition is considerable, unmet health needs after transition cannot all be attributed to poor transitional health care. The range and continuation of needs of young people with cerebral palsy argue for close liaison between adult services and child services and creation of models of practice to improve coordination.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, parents, transition, unmet needs

1. INTRODUCTION

For young people with long‐term health conditions, having to move from child to adult health care services may be challenging. In common with other young people, they are beginning to take on the responsibilities of an adult whilst at the same time experiencing many physical and psychological changes; they may be taking exams, looking for work, exploring new relationships, and planning future education at the same time as being discharged from child health services. A number of official reports have identified the need to improve health care transfer (e.g., UK: [Chief Medical Officer, 2013, Kennedy, 2010]; USA [American Academy of Pediatrics et al., 2011] reaffirmed 2015). There is a small published literature on the effectiveness of transitional care across conditions (Crowley, Wolfe, Lock, & Mckee, 2011; Gorter et al., 2015; Sonneveld, Strating, Van Staa, & Nieboer, 2013), but little agreement about how to measure outcomes beyond clinic attendance (Coyne, Hallowell, & Thompson, 2017; Sharma, O'hare, Antonelli, & Sawicki, 2014).

Any change of health service provider(s) may be particularly difficult to negotiate for young people with a complex physical impairment such as cerebral palsy (CP) because of the range of difficulties they may have and the need for coordination of services. This applies to both child and adult provision, and for this reason may be a particular challenge for services around the time of health care transfer as young people approach adulthood (Oskoui, 2012; Oskoui & Wolfson, 2012). In a comprehensive literature review of health care transition services for those with CP or spina bifida (149 articles), Binks and colleagues (2007) identified five elements supporting a positive transition to adulthood (preparation, flexible timing, co‐ordination, transition clinics, interested adult providers), but they found little empirical evidence. Indeed, the literature on health care transition repeatedly demonstrates that young people have difficulties with access to clinical care once they transfer from child services (Stam, Hartman, Deurloo, Groothoff, & Grootenhuis, 2006), hence the need for guidelines on how transition should be improved (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2016).

How can satisfactory clinical care for a young person with CP be measured? Individuals with CP have a range of health needs arising directly from their condition (such as spasticity or epilepsy) and as secondary effects (such as pain and mobility problems). One approach to measurement of care is to ask about unmet health needs. A “health need” is present when a patient requires a health service to help minimise the impact of their condition or manage their functional disability; this would be an “unmet health need” when the individual reports that the service is not provided or is not adequate. Unmet health needs have been used as a quantifier of health care to allow monitoring through patient report (Fulda, Johnson, Hahn, & Lykens, 2013) and to direct appropriate allocation of resources to different patient groups (Brown et al., 2011).

We conducted a search of literature on unmet health needs for children with disabilities in order to examine the properties of measures of unmet need. Ovid Medline was searched from 1996 to July 2016, using search terms related to disabled children, health services research, and health service needs and demands. A “seminal” search used Google Scholar to expand the enquiry by searching for “unmet need” in the title of references. Data were extracted from each relevant paper on quantitative methods of measurement, scoring of unmet need, and statistical analysis; this was conducted separately by two reviewers and then recorded by consensus. Relevant papers had similarities in measurement of perceived unmet needs to a landmark report about unmet needs of parents of disabled children (Quine & Pahl, 1989) or used a method of measurement of unmet need for relevant services (Schmidt, Thyen, Chaplin, Mueller‐Godeffroy, & European, 2007). All other papers were rejected, usually because they focused on one reported need only, were commentaries on unmet need, or were reviews of papers, rather than quantitative analyses.

The initial search yielded 416 articles. Data were extracted from 11 relevant papers (see Table 1). The number of items included in questionnaires have varied according to the purpose of the study and the age range and type of disabilities of participants. Several types of response systems had been used to analyse unmet health needs, the most common coding being one with three points: “help not needed,” “getting enough help,” and “not getting enough help.” This can yield a total of perceived needs, a frequency of reported unmet needs, or a proportion of unmet needs to total needs. Other than reports of content validity and three papers, which considered the internal consistency of the questionnaire, no studies have carried out examination of the measurement properties of scoring unmet health needs, despite use of scores in multivariate analyses.

Table 1.

Papers that report measurement of unmet health needs of disabled children

| Research paper | Descriptive statistics | Internal consistency | Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress and coping in families caring for a child with severe mental handicap: A longitudinal survey (Quine & Pahl, 1989). | 22 items (parents). Proportion of unmet need | Yes | Stepwise multiple regression analysis, perceived need as outcome | |

| Service needs of families of children with severe physical disability (Sloper & Turner, 1992). | 23 items. Mean total service need for specific domains | Yes | Stepwise multiple regression analysis, unmet need as predictor | |

| Expert opinions—A national survey of parents caring for a severely disabled child (Beresford, 1995). | 12 items (child), 15 items (parent). Frequency of unmet need | Yes | ||

| Unmet health care needs and impact on families with children with disabilities in Germany (Thyen et al., 2003). | 14 items. Mean total unmet need for specific domains | Yes | Multiple regression, unmet need as predictor | |

| Key worker services for disabled children: What characteristics of services lead to better outcomes for children and families? (Sloper, Greco, Beecham, & Webb, 2006). | 23 items. Sum of unmet need | α = .77 (child), α = .85 (parent) | Yes | Path analysis, unmet need as outcome |

| Survey of behaviour problems in children with neuromuscular diseases (Darke, Bushby, Le Couteur, & Mcconachie, 2006). | 13 items. Overall unmet need score for certain areas | Yes | No | |

| Cross‐cultural development of a child health care questionnaire on satisfaction, utilization, and needs (Schmidt et al., 2007). | 15 items. Overall unmet need score | Yes (each item) | No | |

| Beyond an autism diagnosis: Children's functional independence and parents' unmet needs (Brown et al., 2011). | 51 items. Proportion of unmet need | α = .90 (family needs) | Yes | Multiple regression (backwards deletion), unmet need as outcome |

| Unmet needs of families of school‐aged children with an autism spectrum disorder (Brown, Ouellette‐Kuntz, Hunter, Kelley, & Cobigo, 2012). | 51 items. Proportion of unmet need | α = .92 | No | No |

| Do unmet needs differ geographically for children with special health care needs? (Fulda et al., 2013). | 9 items. Proportion of unmet need | Yes | Multiple regression, unmet need as outcome | |

| Unmet health care service needs of children with disabilities in Penang, Malaysia (Tan, 2015). | 17 items. Mean proportion of unmet need | Yes |

The Transition Research Programme (Colver et al., 2013; http://www.research.ncl.ac.uk/transition) was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research and aims to investigate and provide evidence as to how British national health services can contribute to the successful transition of young people with long‐term conditions. One exemplar condition in this programme was CP. In this paper, we examine data from the Research Programme to examine how well health needs of young people with CP were met and describe how we investigated the measurement properties of the instrument used to assess unmet needs. Our main research hypothesis was that during transition, the unmet health needs of young people would increase.

Key messages.

Questionnaires about the unmet health needs of individuals with disabilities can be described meaningfully through factor analysis, yielding a small number of domains that can then be used in quantitative analysis

Young people with cerebral palsy at the start of transition from child services have a range of unmet health needs. Therefore, unmet health needs towards the end of transition cannot all be attributed to poor transitional health care.

Nevertheless, parent and young person reported unmet health needs do tend to increase during transition, especially with respect to management of pain, bone or joint problems, and speech.

Paediatric care tends to be coordinated by a paediatrician with a clinical overview of the condition; a similar clinical overview, undertaken by an adult physician, might be appropriate for all adults with cerebral palsy.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Within the Transition Research Programme, there is a longitudinal study whose protocol is published (Colver et al., 2013). In summary, young people joined the longitudinal study at ages 14 to 18 years 11 months and before they had transferred to adult health care. They were then visited at home annually on four occasions by research assistants who oversaw the completion of questionnaires and other data about socio‐economic factors, health service use, and well‐being.

The young people with CP were recruited through two regional population registers in North East England and Northern Ireland, and through a clinical paediatric service in Norfolk (Merrick et al., 2015). One parent of each young person was also recruited. Participants did not differ on severity of disability (as measured by the Gross Motor Function Classification System [GMFCS] at age 5 years) from those of the same age in the regional registers (Merrick et al., 2015). Young people with severe learning difficulties were excluded as, for our study, young people had to be able to self‐report their health needs.

2.2. Unmet needs questionnaire

The unmet needs questionnaire created for the longitudinal study asked about 11 aspects of health care needs of people with CP (rather than educational or social needs). Further, they are health care needs arising from CP rather than from unrelated conditions. Items were selected (by Author 2) based on extensive clinical and research experience of working with young people with CP, and taking account of needs captured in a number of research studies and an audit of medical care in the Northern region of UK (Horridge, Tennant, Balu, & Rankin, 2015; Jackson, Krishnaswami, & Mcpheeters, 2011; Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2008). The chosen items covered speech, mobility, positioning, equipment, pain, epilepsy, weight, control of movement, bone or joint problems, curvature of back, and eyesight. Items were coded from linked questions as “help not needed,” “getting enough help,” or “need more help,” with the last two categories establishing a reported “need” and the last category considered as “unmet need.” One example of the linked questions is “Do you have pain?” If yes, “Has it been discussed with health professionals?;” “Is the problem of pain being addressed?” The questionnaire was completed separately by the young person and also by the parent (about the young person), as their perspectives are related but may differ.

The responses were converted into the proportion of unmet needs to total needs (Brown et al., 2011). In order to examine the structure of the questionnaire items, we undertook categorical principal component analysis (CatPCA) on baseline data. The lowest number of components that encompassed the maximum number of items was selected for rotated CatPCA. Rotated CatPCA provided component‐weighted item scores that were used to calculate unmet needs for each component for each individual. The suitability of the data for factor analysis was confirmed by analysis of the correlation matrix, the Kaiser‐Meyer‐Oklin value (KMO; Cerny & Kaiser, 1977), and Bartlett's test of sphericity (Snedecor & Cochran, 1989).

2.3. Other measures

Impairment severity: The GMFCS (Palisano et al., 1997) was completed by the research assistant in discussion with the young person and their parent. It describes five levels of severity of restriction of function; Levels IV and V were grouped as few young people in the study were classified at Level V.

Socio‐demographic data: Questionnaires completed by young people and parents gave information on household income, young person's education, number of siblings in the family, and geographical location. Income was grouped as above or below £31,000, in line with the UK mean income in 2016 (Office for National Statistics, 2016). Education was grouped as specialist (special school or unit in mainstream school) or nonspecialist. The variable “siblings” was dichotomised as no other children/one or more others in the household. Geographical location was either North East England, Northern Ireland, or Norfolk, three dispersed UK regions.

For each young person, the date of their last appointment in child services was noted; also recorded for each visit after baseline was whether or not the child had transferred from child services.

2.4. Analysis

The factors identified in the CatPCA and the additional measures were examined for bivariate relationships using one‐way analysis of variance or t test at baseline. Descriptive statistics are presented for change in unmet needs over the four research visits. For prediction of unmet needs over time, hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted to examine whether the independent variables, including whether transferred from child services, predicted the young person and parent reported unmet needs component scores at the final research visit.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Psychometric analysis of questionnaire

One hundred six young people with CP and their parents were recruited (see Table 2). In examination of item‐total correlations, it became apparent that the way in which the questions about weight had been asked was insufficient. The questions were “Are you weighed each year at a clinic?” and if yes, “Has it been discussed as to whether satisfactory, overweight, or underweight?” The item did not establish whether a need was being addressed as was the case for all other items. Therefore, the item weight was removed from further analysis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the young people with cerebral palsy (n = 106)

| Characteristic | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 16.40 | 1.27 |

| Number | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 46 | 43.4 |

| Male | 60 | 56.6 |

| GMFCS level | ||

| I | 53 | 50.0 |

| II | 20 | 18.9 |

| III | 15 | 14.1 |

| IV and V | 18 | 17.0 |

| Educationa | ||

| Specialist setting | 46 | 43.8 |

| Nonspecialist setting | 59 | 56.2 |

| Area | ||

| North East England | 49 | 46.2 |

| Northern Ireland | 46 | 43.4 |

| Norfolk | 11 | 10.4 |

| Siblingsa | ||

| None | 29 | 27.6 |

| None or more | 76 | 72.4 |

| Household incomeb | ||

| <£31,000 | 32 | 46.4 |

| ≥£31,000 | 37 | 53.6 |

Note. GMFCS = Gross Motor Function Classification System.

One missing.

Two missing, 35 would rather not say or did not know.

The data on proportion reporting needs and unmet needs are presented in Table 3. Parents generally identified more needs than young people did, but agreement was high; where both reported unmet needs, the paired samples correlation was r = .69 (p < .001). The areas of greatest reported unmet need concerned speech, pain, and bone or joint problems.

Table 3.

Needs reported by young people and parents (n = 106) at baseline and unmet need as a proportion of reported needs

| Item | Young person | Parent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage with reported needs | Mean unmet needa | Percentage with reported needs | Mean unmet needa | |

| Speech | 21.7 | 0.39 | 19.0b | 0.60 |

| Mobility | 58.4 | 0.12 | 68.9 | 0.25 |

| Positioning | 25.5 | 0.14 | 38.1b | 0.30 |

| Equipment | 56.2b | 0.20 | 61.9b | 0.29 |

| Pain | 34.0 | 0.38 | 50.0 | 0.43 |

| Epilepsy | 17.9 | 0.15 | 18.8 | 0.05 |

| Control of movement | 63.2 | 0.31 | 73.6 | 0.28 |

| Bone or joint problems | 41.5 | 0.45 | 58.5 | 0.35 |

| Curvature of back | 24.7b | 0.30 | 29.5b | 0.32 |

| Eyesight | 45.3 | 0.10 | 47.2 | 0.08 |

Unmet need as a proportion of reported needs.

One missing.

The data proved suitable for principal component analysis (CatPCA). For the young people's responses, the KMO value, at 0.66, was greater than the recommended minimum of 0.6, and reached statistical significance at p < .001 according to Bartlett's test of sphericity recommendation of p < .05. For parents' responses, the respective coefficients were KMO = 0.7 and Bartlett p < .001.

The CatPCA for young people generated three components with eigenvalues exceeding one, each explaining 21.8%, 15.3%, and 11.2% of the variance. Most items loaded weakly on the third component (<0.4 but above 0.32 as recommended; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013) and also loaded more strongly on the first or second component (>0.4). The third component was therefore removed, and this left two components for Varimax rotation (see Table 4). Component 1, labelled as daily living health care, explained 20.9% of the variance: speech, mobility, positioning, equipment, and control of movement. Internal consistency was α = .58. Component 2, labelled as medical care, explained 16.2%: pain, epilepsy, bone or joint problems, curvature of back, and eyesight. Internal consistency was very low at α = .13.

Table 4.

Factor loadings for unmet need scores

| Young person | Parent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Component | |||

| Item | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Speech | 0.53 | 0.33 | ||

| Mobility | 0.74 | 0.82 | ||

| Positioning | 0.71 | 0.82 | ||

| Equipment | 0.70 | 0.84 | ||

| Pain | 0.70 | 0.77 | ||

| Epilepsy | −0.49 | |||

| Control of movement | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.39 | |

| Bone or joint problems | 0.52 | 0.55 | ||

| Curvature of back | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.39 | |

| Eyesight | 0.35 | −0.41 | −0.50 | |

Bold font represents allocation to factors.

The CatPCA for parents' questionnaires generated four components with eigenvalues exceeding one, respectively, explaining 25.8%, 14.9%, 11.5%, and 10.3% of the variance. Items loading strongly on Components 3 and 4 also loaded on Components 1 and 2. Because more items loaded on Components 1 and 2, Component 3 was removed. As there was only one item, epilepsy, loading strongly on Component 4, this item was removed; only one parent identified their young person having unmet needs with regard to epilepsy. This left two components for Varimax rotation. Component 1 daily living health care, explained 27.8% of the variance (Cronbach's α = 0.75), and Component 2, medical care, explained 17.2% of the variance (Cronbach's α = 0.48). For parents, the control of movement item loaded similarly on both components but higher on medical care, whereas for young people, it loaded with daily living health care. Factor scores for each item were calculated by multiplying proportion unmet need scores by the component weighting.

3.2. Bivariate analysis

The daily living health care unmet need score was significantly higher for those with more severe motor impairment (GMFCS level) as reported by both young people, F(3, 101) = 10.39, p < .001, and parents, F(3, 99) = 14.04, p < .001. For the medical care unmet need score, there were no significant differences (p > .05) by GMFCS levels. For those in a nonspecialist education setting, there were significantly higher unmet needs reported for daily living health care by both young people (t = −2.02, p = .05) and parents (t = −2.59, p = .01) than for young people in a specialist education setting; there were no significant differences for the medical care scores.

Analysis by geographical location, number of siblings, and disposable household income revealed no significant differences by factor scores at baseline, whether young person or parent reported.

Parents reported a higher level of daily living health care unmet needs than did young people (t = −2.06, p = .04) and of medical care unmet needs (t = −3.15, p = .002).

3.3. Longitudinal follow‐up

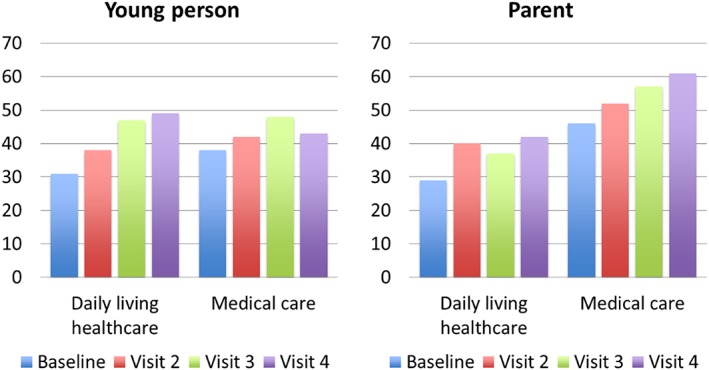

The proportion of young people at the four time points who reported some unmet needs is shown in Figure 1. The pattern shows an increase over time, with more young people reporting unmet needs in daily living health care whereas parents of the young people were particularly likely to identify some unmet needs for their young person's medical care.

Figure 1.

Percentage of young people with unmet needs over time

Over time, parents continued to report a higher level of unmet needs on the daily living health care and medical care factor scores than their young person did (see Table 5, n = 69 young people with data for all visits) and unmet needs tended to increase. Our main research hypothesis was that during transition, the overall unmet health needs of young people would increase, but none of the changes was significant (young person daily living health care Wilk's Lambda = 0.95, p = .30, medical care Wilk's Lambda = 0.96, p = .41; parent daily living health care Wilk's Lambda = 0.97, p = .54, medical care Wilk's Lambda = 0.92, p = .19).

Table 5.

Level of unmet need (factor scores) reported over time (n = 69)

| Young person | Parent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily living health care | Medical care | Daily living health care | Medical care | |

| Baseline | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| Visit 2 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.54 |

| Visit 3 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.55 |

| Visit 4 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.51 |

There was attrition over the four visits. To maximise numbers, the “final visit” to young people was defined as either Visit 4 or as Visit 3 if Visit 4 was not completed (mean interval 2 years 11 months, range 2 years to 3 years 7 months); 74 young people had a final visit thus defined (69.8%). There were no significant differences (p > .05) between those retained in the study and those who dropped out before the final visit in terms of age, gender, GMFCS level, education setting, siblings, or geographical location. Those who had reported their household income to be £31,000 or greater were more likely to have been retained for a final visit (chi square = 4.43, p = .04).

By the time of the final visit, 86% (64) of the young people had transferred from child services (35 [55%] to adult services and 29 [45%] to general practitioner). In order to test whether transfer from child services might be associated with increased unmet needs, a repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted to compare differences in the mean factor scores between baseline and final visit for young people and parents, depending on whether they had transferred. There were increases in unmet need factor scores as reported by both young people and parents; however, none of the interaction terms was significant.

3.4. Hierarchical multiple regression

Logarithmic transformation of the final visit factor scores acting as the dependent variable (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013) was required to improve the normality and homoscedasticity of the standardised residuals. As some factor scores were zero, 0.1 was added to all the factor scores before the logarithmic transformation. The independent variables were age, gender, GMFCS, education setting, and the baseline score for the dependent variable, as well as whether the young person had transferred from child services by the final visit.

The regression model for the young person daily living health care scores at the final visit was significant and accounted for 30.1% of the variance. The only significant predictor in the final model was level of physical functioning (GMFCS; see Table 6). The regression model for the parent daily living health care scores at the final visit was significant and accounted for 42% of the variance. Only the parent daily living health care score from baseline predicted the final visit parent daily living health care scores.

Table 6.

Result of hierarchical multiple regression predicting final scores for unmet needs in daily living health care of young people with cerebral palsy (n = 74)

| Predictor | Young person | Parent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | β | SE | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Age | −0.09 | 0.10 | −0.09 | 0.14 |

| Gender | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Baseline daily living health care unmet needs | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.42*** | 0.07 |

| R 2 change | 0.09* | 0.36*** | ||

| Step 3 | ||||

| GMFCS | 0.17*** | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Education setting | −0.08 | 0.11 | −0.19 | 0.13 |

| Transfer by final visit | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.17 |

| R 2 change | 0.17** | 0.04 | ||

| R 2 | 0.30 | 0.42 | ||

Note. GMFCS = Gross Motor Function Classification System; SE = standard error.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The regression models for the young person and parent medical care scores for the final visit were not significant (p > .05).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Main findings

This longitudinal study of young people with CP at the stage of making the transition from child health care services indicates a high level of needs, especially in areas such as mobility, control of movement, and equipment. These are obstacles to daily living, and there is a continuing need for supportive health care services into adulthood. Somewhat fewer young people and parents reported a need in terms of management of pain, and of bone and joint problems; however, these areas of need for medical care were amongst the highest where needs were not adequately met.

There was a tendency for the proportion of young people with unmet needs, and also the level of individual need, to increase over the 3‐year study, in line with our initial hypothesis (though not statistically significant). However, in this sample, whether the young person had transferred out of child services did not seem to be a key factor. Those with higher unmet need in daily living health care at baseline or with higher levels of impairment in physical functioning were found to have greater unmet need at the end of the study. It was noticeable that those in nonspecialist education settings at the start of the study tended to have greater unmet need for daily living health care, possibly indicating that therapy services are harder to organise when not provided within (special) school (Hemmingsson, Gustavsson, & Townsend, 2007).

4.2. Scoring unmet needs

Our work has shown that an unmet needs questionnaire structure can be described meaningfully through a factor analysis, yielding a small number of domains that can then be used in quantitative analysis. The factor scores derived are not generalizable as the results of principal component analysis apply only to the sample in any particular study, and the items chosen for an unmet needs questionnaire will vary with the sample and the focus. Nevertheless, this study provides a model for how greater structural validity could be achieved in studies of unmet health needs. Several questionnaire scoring systems have been used previously to analyse the unmet health needs of children with disabilities (and/or their parents), and correlations found with other measured variables such as impact on the family or income (Brown et al., 2011; Thyen, Sperner, Morfeld, Meyer, & Ravens‐Sieberer, 2003) and geographical location (Fulda et al., 2013). However, there is little published evidence of investigation of the measurement properties of such scoring systems.

A somewhat similar questionnaire has been validated for adults with physical disability, the Southampton Needs Assessment Questionnaire (Kersten, Mclellan, George, & Smith, 2000). The Southampton Needs Assessment Questionnaire has shown good validity (content, coverage, and construct), internal reliability, sensitivity, and responsiveness, but further studies are needed to define the consequences of rehabilitation services meeting or not meeting the identified needs. A U.S. study of children and adults with CP used a single dichotomous variable within a national dataset from 2001 to 2006 with 600 subjects, comparing unmet need between those with CP and those with other special health care needs, and found no difference (Jackson et al., 2011). However, that study did show that associated medical problems in those with CP increased unmet need. Interrogation of the same data set showed considerable geographical variation across the United States (Fulda et al., 2013). Geographical variation was not found significant in our U.K. study of 106 young people. A Dutch study (Nieuwenhuijsen et al., 2008) of 46 young adults with CP found that those with more severely affected gross motor functioning had more unmet needs and visited various health care professionals more often than did young adults with better gross motor functioning, in line with our findings. Thus, it appears that there is still work to be done on accurate measurement of unmet needs, for both children and adults.

4.3. Limitations

One limitation of our findings is that they only apply to those young people with CP without severe learning difficulties. The items in the questionnaire were not selected through consultation with young people or their parents. The factors identified were a suitable model to describe the unmet needs questionnaire in this study; however, the internal consistency of the factor scores was mostly low, indicating the diversity of needs of the young people. The item about management of weight was excluded because of how the question was asked; addressing needs related to weight of individuals with CP is, however, obviously important. The retention rate of 70% did not bias the sample with respect to severity, age, sex education setting, or geographical location. This rate of retention is comparable to that of other longitudinal studies involving young people. For example, a study following young people with attention deficit disorder over 3 years as they moved to adult services reported a retention rate of 58.2% for three visits and 81.3% for at least two visits (Eklund et al., 2016). The predictors included in our study did not include amount and type of services received; this issue will be addressed for transitional health care services in the final report of the Transition Research Programme.

4.4. Directions for future research

This study exemplifies why longitudinal studies are important, particularly at a key point of transition of health care providers. Cross‐sectional studies, both qualitative and quantitative, have clarified the nature of the problems faced by young people with CP and other long‐term conditions. But future research needs to follow young people over time, to understand better how best to meet their needs and to explore barriers and facilitators to having those needs met. These will include personal relationships with clinicians, but also factors such as moving away to college, busy lives, reluctance to focus on “disability,” and lack of information. Only with this fuller understanding can service models be designed appropriately. More broadly, key questions for the field of transition include how to define “successful health care transition,” and whether it improves health‐related outcomes for young adults (Sharma et al., 2014).

It would be timely to review explicitly the concept of “unmet health needs,” how it has been used in research and reports, its measurement, and the major predictors across disabling conditions. This study looked only at one particular way of asking about and quantifying unmet needs of young people. As a way of monitoring services and outcomes in research and practice, there is a need to clarify the concept and come to conclusions about the most robust measurement approach.

4.5. Implications of the findings

We found that many young people with CP had unmet health needs at the start of their transition from child health services. Therefore, when studying the health care needs of young adults with CP, it would be misleading to attribute their situation only to inadequacy of transitional care. Nevertheless, there was a tendency in our study for overall unmet health needs to increase during the 3 years of the study while the young people were in transition. How to respond to this issue of the need for continuity and coordination of services was the purpose of the literature review by Binks and colleagues; as mentioned in the introduction, they identified five key service elements that were repeatedly recommended, but found almost no empirical evidence to support these (Binks et al., 2007). A small qualitative study of nine young adults with CP used focus groups to explore what kind of preparation for transition the young adults had received; the researchers concluded that there was a need for navigators and facilitators of transition (Bagatell, Chan, Rauch, & Thorpe, 2017).

Worryingly for the high level of reported needs in our study, there is great variety of current practice for transitional care of those with CP. A recent U.S. study surveyed physicians providing services to adolescents (Bolger, Vargus‐Adams, & Mcmahon, 2017), and the main recommendation was that there should be a multidisciplinary clinic in the adult health care setting. Paediatric providers identified significant problems with adult services who were unwilling to accept patients, concerns that adult providers and/or the adult health care system do not provide the same level of care, and lack of financial resources associated with adult health care providers. Cassidy and colleagues (2016) examined in Canada the extent to which physiatrists (known as adult rehabilitation physicians in the UK) provided care to adults with CP and barriers to their involvement. They found that most physiatrists cared for fewer than five adults with CP, but an important reason for this was lack of referrals. In the UK, part of the Transition Research Programme has documented the very limited extent to which young people with CP have received elements of transitional care that have been recommended repeatedly in government and other policy reports (NICE, 2016). Although 48% young people during transition reported that professionals had discussed with them how to take increasing responsibility for their health, only 6% reported having a written transition plan, and only 13% had attended an age‐banded clinic or met a member of the adult team (Transition Research Programme final report).

The guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence for management of CP in the under 25 s recommends that there should be clear pathways for transition involving the young person's general practitioner (primary care physician) and a named professional in adult services with an interest in the management of CP (NICE, 2017). Yet in the UK, there is a lack of such adult specialists; and referral criteria to adult services are correspondingly restrictive. Although separate referrals may be needed to neurologists, orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists, pain specialists, spasticity specialists, and so on to address the range of needs of an individual with CP, there may be a case for identifying a professional who takes a clinical overview and who can assist the young person to navigate the services they require as an adult. In some cases, this might be the general practitioner, but this presupposes that the general practitioner has been kept well informed and involved when the young person was attending paediatric services. Alternatively, increased availability of rehabilitation specialists for adults (or physiatrists) is a service model worthy of wider investigation.

This study has shown that a considerable proportion of more able young people with CP have continuing health care needs throughout later adolescence and early adulthood. They thus require ongoing support into adult health care in managing aspects of daily living such as mobility and positioning, and medical care to help reduce pain, bone and joint problems, and so on. How best to meet these needs is a challenge in the current climate of apparent increasing demand and constrained resources for health care provision.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This paper summarises independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research scheme (RP‐PG‐0610‐10112). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all the young people and family members who contributed to the Transition Programme longitudinal study and to the research assistants who collected data: Guiomar Garcia Jalon; Hannah Merrick, Holly Roper, and Louisa Fear. We acknowledge the support of the NIHR Clinical Research Network. Folasade Solanke received a Newcastle University vacation scholarship in support of the work.

The Transition Collaborative Group consists of the authors of this paper; other co‐applicants: Angela Bate, Caroline Bennett, Gail Dovey‐Pearce, Ann Le Couteur, Janet McDonagh, Jeremy R Parr, Mark Pearce, Tim Rapley, Debbie Reape, and Luke Vale; advisors: Nichola Chater and Helena Gleeson; local investigators: Anastasia Bem, Tim Cheetham, Mark Linden, Maria Lohan, John Macfarlane, and Nandu Thalange.

Solanke F, Colver A, McConachie H, On behalf of the Transition collaborative group . Are the health needs of young people with cerebral palsy met during transition from child to adult health care? Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44:355–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12549

REFERENCES

- American Academy of Pediatrics , American Academy of Family Physicians , American College of Physicians , Transitions Clinical Report Authoring Group , Cooley, W. C. , & Sagerman, P. J. (2011). Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics, 128, 182–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagatell, N. , Chan, D. , Rauch, K. K. , & Thorpe, D. (2017). “Thrust into adulthood”: Transition experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy. Disability and Health Journal, 10, 80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beresford, B. (1995). Expert Opinions: A national survey of parents caring for a severely disabled child. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binks, J. A. , Barden, W. S. , Burke, T. A. , & Young, N. L. (2007). What do we really know about the transition to adult‐centered health care? A focus on cerebral palsy and spina bifida. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88, 1064–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, A. , Vargus‐Adams, J. , & Mcmahon, M. (2017). Transition of care in adolescents with cerebral palsy: A survey of current practices. Phys Med Rehab, 9, 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H. K. , Ouellette‐Kuntz, H. , Hunter, D. , Kelley, E. , Cobigo, V. , & Lam, M. (2011). Beyond an autism diagnosis: Children's functional independence and parents' unmet needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1291–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H. K. , Ouellette‐Kuntz, H. , Hunter, D. , Kelley, E. , & Cobigo, V. (2012). Unmet needs of families of school‐aged children with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 25, 497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, C. , Campbell, N. , Madady, M. , & Payne, M. (2016). Bridging the gap: The role of physiatrists in caring for adults with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 38, 493–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerny, C. , & Kaiser, H. (1977). A study of a measure of sampling adequacy for factor‐analytic correlation matrices. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 12, 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chief Medical Officer (2013). Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2012. Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays. London. [Google Scholar]

- Colver, A. F. , Merrick, H. , Deverill, M. , Le Couteur, A. , Parr, J. , Pearce, M. S. , … McConachie, H. (2013). Study protocol: Longitudinal study of the transition of young people with complex health needs from child to adult health services. BMC Public Health, 13, 675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, B. , Hallowell, S. C. , & Thompson, M. (2017). Measurable outcomes after transfer from pediatric to adult providers in youth with chronic illness. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley, R. , Wolfe, I. , Lock, K. , & Mckee, M. (2011). Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 96, 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke, J. , Bushby, K. , Le Couteur, A. , & McConachie, H. (2006). Survey of behaviour problems in children with neuromuscular diseases. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 10, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, H. , Cadman, T. , Findon, J. , Hayward, H. , Howley, D. , Beecham, J. , … Glaser, K. (2016). Clinical service use as people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder transition into adolescence and adulthood: A prospective longitudinal study. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda, K. G. , Johnson, K. L. , Hahn, K. , & Lykens, K. (2013). Do unmet needs differ geographically for children with special health care needs? Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter, J. W. , Stewart, D. , Cohen, E. , Hlyva, O. , Morrison, A. , Galuppi, B. , … Group, T. S. (2015). Are two youth‐focused interventions sufficient to empower youth with chronic health conditions in their transition to adult healthcare: A mixed‐methods longitudinal prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 5, e007553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmingsson, H. , Gustavsson, A. , & Townsend, E. (2007). Students with disabilities participating in mainstream schools: Policies that promote and limit teacher and therapist cooperation. Disability & Society, 22, 383–398. [Google Scholar]

- Horridge, K. , Tennant, P. W. , Balu, R. , & Rankin, J. (2015). Variation in health care for children and young people with cerebral palsies: A retrospective multicentre audit study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 57, 844–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, K. E. , Krishnaswami, S. , & Mcpheeters, M. (2011). Unmet health care needs in children with cerebral palsy: A cross‐sectional study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2714–2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, I. (2010). Getting it right for children and young people. London: Overcoming cultural barriers in the NHS so as to meet their needs. [Google Scholar]

- Kersten, P. , Mclellan, L. , George, S. , & Smith, J. A. (2000). The Southampton Needs Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ): A valid tool for assessing the rehabilitation needs of disabled people. Clinical Rehabilitation, 14, 641–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, H. , McConachie, H. , Le Couteur, A. , Mann, K. , Parr, J. R. , Pearce, M. S. , … Transition Collaborative, G. (2015). Characteristics of young people with long term conditions close to transfer to adult health services. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2016). Transition from children's to adults' services for young people using health or social care services. London.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2017). Cerebral palsy in under 25s: assessment and management. London. [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, C. , Van Der Laar, Y. , Donkervoort, M. , Nieuwstraten, W. , Roebroeck, M. E. , & Stam, H. J. (2008). Unmet needs and health care utilization in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30, 1254–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics . (2016). Nowcasting household income in the UK: Financial year ending 2016. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/nowcastinghouseholdincomeintheuk/2015to2016 (21 May 2017)

- Oskoui, M. (2012). Growing up with cerebral palsy: Contemporary challenges of healthcare transition. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences, 39, 23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskoui, M. , & Wolfson, C. (2012). Current practice and views of neurologists on the transition from pediatric to adult care. Journal of Child Neurology, 27, 1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palisano, R. , Rosenbaum, P. , Walter, S. , Russell, D. , Wood, E. , & Galuppi, B. (1997). Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 39, 214–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quine, L. & Pahl, J. (1989). Stress and coping in families caring for a child with severe mental handicap: A longitudinal study. Institute of Social and Applied Psychology and Centre for Health Services, University of Kent at Canterbury.

- Schmidt, S. , Thyen, U. , Chaplin, J. , Mueller‐Godeffroy, E. , & European, D. G. (2007). Cross‐cultural development of a child health care questionnaire on satisfaction, utilization, and needs. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7, 374–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N. , O'hare, K. , Antonelli, R. C. , & Sawicki, G. (2014). Transition care: Future directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Academic Pediatrics, 14, 120–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper, P. , & Turner, S. (1992). Service needs of families of children with severe physical disability. Child: Care, Health and Development, 18, 259–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloper, P. , Greco, V. , Beecham, J. , & Webb, R. (2006). Key worker services for disabled children: What characteristics of services lead to better outcomes for children and families? Child: Care, Health and Development, 32, 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor, G. , & Cochran, W. (1989). Statistical Methods. Iowa: Iowa State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sonneveld, H. M. , Strating, M. M. , Van Staa, A. L. , & Nieboer, A. P. (2013). Gaps in transitional care: What are the perceptions of adolescents, parents and providers? Child: Care, Health and Development, 39, 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam, H. , Hartman, E. E. , Deurloo, J. A. , Groothoff, J. , & Grootenhuis, M. A. (2006). Young adult patients with a history of pediatric disease: Impact on course of life and transition into adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. , & Fidell, L. (2013). Using Multivariate Statistics. Pearson: California State University. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S. H. (2015). Unmet health care service needs of children with disabilities in Penang, Malaysia. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27, 41S–51S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thyen, U. , Sperner, J. , Morfeld, M. , Meyer, C. , & Ravens‐Sieberer, U. (2003). Unmet health care needs and impact on families with children with disabilities in Germany. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 3, 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]