Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to monitor the effect of humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) delivered into the open abdomen of mice, simulating laparotomy.

Methods

Mice were anaesthetized, ventilated and subjected to an abdominal incision followed by wound retraction. In the experimental group, a diffuser device was used to deliver HWCO2; the control group was exposed to passive air flow. In each group of mice, surgical damage was produced on one side of the peritoneal wall. Vital signs and core temperature were monitored throughout the 1‐h procedure. The peritoneum was closed and mice were allowed to recover for 24 h or 10 days. Tumour cells were delivered into half of the mice in each cohort. Tissue was then examined using scanning electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

Results

Passive air flow generated ultrastructural damage including mesothelial cell bulging/retraction and loss of microvilli, as assessed at 24 h. Evidence of surgical damage was still measurable on day 10. HWCO2 maintained normothermia, whereas open surgery alone led to hypothermia. The degree of tissue damage was significantly reduced by HWCO2 compared with that in controls. Peritoneal expression of hypoxia inducible factor 1α and vascular endothelial growth factor A was lowered by HWCO2. These effects were also evident at the surgical damage sites, where protection from tissue trauma extended to 10 days. HWCO2 did not reduce tumorigenesis in surgically damaged sites compared with passive air flow.

Conclusion

HWCO2 diffusion into the abdomen in the context of open surgery afforded tissue protection and accelerated tissue repair in mice, while preserving normothermia.

Surgical relevance.

Damage to the peritoneum always occurs during open abdominal surgery, by exposure to desiccating air and by mechanical trauma/damage owing to the surgical intervention. Previous experimental studies showed that humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) reduced peritoneal damage during laparoscopic insufflation. Additionally, this intervention decreased experimental peritoneal carcinomatosis compared with the use of conventional dry‐cold carbon dioxide.

In the present experimental study, the simple delivery of HWCO2 into the open abdomen reduced the amount of cellular damage and inflammation, and accelerated tissue repair. Sites of surgical intervention serve as ideal locations for cancer cell adhesion and subsequent tumour formation, but this was not changed measurably by the delivery of HWCO2.

Short abstract

Reduced tissue injury

Introduction

Open abdominal surgery implicitly involves exposure of visceral and parietal peritoneal tissue surfaces to the external atmosphere. The modern surgical environment demands continuous air exchange (approximately 20 room volumes per h) ideally through high‐efficiency particulate air filtration and laminar flow1. This air flow across moist tissue surfaces leads to desiccation2 and heat loss3. The visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces are encased in a thin layer of mesothelial cells that are heavily augmented by a carpet of numerous microvilli4. These surfaces are the first to show signs of desiccation. These effects are particularly evident during laparoscopy that employs insufflation with dry‐cold carbon dioxide5. Another concern is that peritoneal damage may exacerbate the potential of cancer cells to implant, triggering peritoneal carcinomatosis5.

The nature of abdominal surgery is such that tissue damage is inevitable, posing two important concerns. First, is whether the rate of tissue repair at surgical sites and bystander regions is influenced by passive desiccation. Second, is whether the potential of cancer cells to adhere to sites of damage is worse if induced by desiccation and/or surgical trauma, and whether this influences peritoneal carcinomatosis. Peritoneal carcinomatosis is particularly challenging to manage and affected patients have poor outcomes6. A previous study5 in a preclinical model found that humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) during laparoscopy reduced peritoneal carcinomatosis compared with the use of conventional dry‐cold carbon dioxide.

Here, the delivery of HWCO2 under laparotomy conditions was investigated, in the presence and absence of simulated surgical damage, to evaluate the primary objective of induced hypoxia, tissue damage and tissue repair. Others7 have reported maintenance of oxygenation of the peritoneum with HWCO2 and, in view of these data, the expression of a sentinel marker of hypoxia, hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) 1α, was examined. The secondary objective was to assess changes in the potential of cancer cells to attach to sites of surgical damage.

Methods

Female BALB/c mice aged 7–12 weeks, weighing 17–25 g, were used to develop the open surgery procedure, with the approval of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Mice were purchased from the ARC (Perth, Western Australia, Australia) and housed in the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre facility with a 12‐h light–dark cycle, and free access to food and water. Mice were anaesthetized, intubated, ventilated and placed on a warming pad5, and then divided into two groups: open surgery with exposure to ambient air (control) or open surgery with HWCO2 diffusion (Fig. 1).

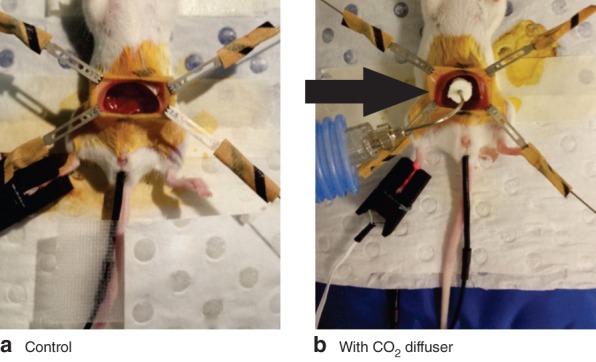

Figure 1.

Laparotomy set‐up using four retractors, intubation tube, PhysioSuite® monitor and rectal probe: a control mouse and b mouse with carbon dioxide diffuser (arrow). Humidified‐warm carbon dioxide is delivered via the diffuser throughout the 1‐h procedure

Monitoring of vital signs

Mice were placed on a heating pad with far‐infrared warming, along with temperature monitoring and a homoeothermic control system that was connected to a PhysioSuite® apparatus (Kent Scientific, Torrington, Connecticut, USA), by which body temperature, arterial oxygen, heart rate and perfusion were monitored and recorded. A paw sensor was applied and a rectal probe (lubricated with eye gel) was inserted under anaesthetic. The entire abdomen was swabbed with iodine solution from the xiphoid process to the lower abdomen. The skin was lifted using sterile surgical forceps directly below the xiphoid process, and an inferior incision made using sterile surgical scissors towards the lower abdomen (1.5–2·0 cm depending on the size of the mouse). The peritoneal incision mirrored the inferior skin incision. Magnetic fixators were used to secure the retractor wires, allowing maintenance of an open abdominal wound; these were attached to the skin but not the peritoneal wall, to minimize unintended mechanical damage.

Delivery of carbon dioxide to the open abdomen

A miniaturized gas diffuser (Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand) was used to reduce flow velocity and effectively fill the abdominal cavity with humidified carbon dioxide. It was positioned in the cavity without touching any organs using a retort stand directly over the open wound to deliver HWCO2 for 1 h. Throughout HWCO2 delivery (30–60 ml/min) there was a parallel decrease in isofluorane level delivered by an intubation tube, from 5 to 4 per cent and decreasing in 0·5‐per cent increments every 5 min to reach 2·5 per cent within 30 min.

Replicating surgical trauma

During the open abdominal procedure, tissue trauma was simulated by a single investigator using sterile plastic serrated forceps on one side of the peritoneum. The gas diffuser was removed and sterile plastic forceps used to rub the peritoneum gently with five strokes to the wall at the 30‐min time point. The gas diffuser was then returned to the open cavity. At the conclusion of the laparotomy, the gas diffuser was removed along with retractors and magnetic fixators. The endotracheal tube was then removed and a head cone applied immediately to continue the delivery of isofluorane/oxygen. The peritoneum was closed using surgical sutures, and the skin by surgical clips.

Tumour cells and retroviral transduction

Murine stem cell virus (MSCV)‐mCherry‐CT268 cells were generated by stable retroviral transduction with an MSCV‐mCherry vector derived by replacing the green fluorescent protein (GFP) coding region of MSCV‐IRES‐GFP (Addgene, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA) with the mCherry coding sequence (Clontech, Mountain View, California, USA). At the end of the procedure, 1000 CT26 cells were delivered into the abdomen in 100 μl phosphate buffered saline, after which the peritoneum and skin were closed.

Tissue analysis

Tissue harvesting and processing, and immunohistochemical (IHC) methods have been described previously5. In brief, sections were stained for expression of cyclo‐oxygenase (COX) 2 (1 : 1000, sc‐1745; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A (1 : 100, DP3520S; Acris, Rockville, Maryland, USA) and HIF‐1α (1 : 400, 0100‐479; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, Colorado, USA), with visualization using horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies. Tissue specimens were examined using a bench‐top scanning electron microscope (JCM‐6000; Jeol, Peabody, Massachusetts, USA) and operated at 15 kV under high vacuum.

Fluorescence image analysis

Tumours on the peritoneum were analysed for CherryRed fluorescence using a Maestro™ 2 imaging apparatus (Cambridge Research & Instrumentation, Woburn, Massachusetts, USA) with a wavelength of 150 nm. The average signal in pixels per tumour area was quantified using the Maestro software package.

Semiquantitative analyses

Mice were killed at 24 h and 10 days. IHC assessment for antigens involved inspection of images generated by Aperio® (Leica Microsystems, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia) and scoring using a histological score (H‐score); the latter was calculated as the product of staining intensity (0, none; 1, weak; 2, moderate; 3, strong) and extent (0, 0–5 per cent; 1, 6–25 per cent; 2, 26–50 per cent; 3, 51–75 per cent; 4, 76 per cent or more). Scanning electron microscopy was used to evaluate changes in morphology; alterations were quantified using a customary scale adapted from the H‐score method and represented as a percentage5.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean(s.d.). Data were analysed using one‐ or two‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, or two‐tailed unpaired t test. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. GraphPad Prism® version 6 (GraphPad, La Jolla, California, USA) was used for statistical evaluation.

Results

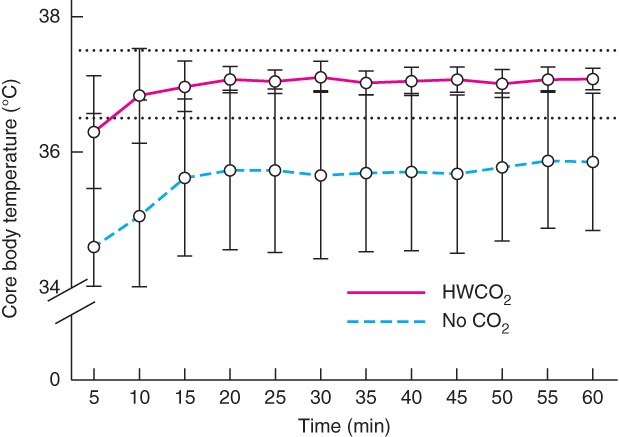

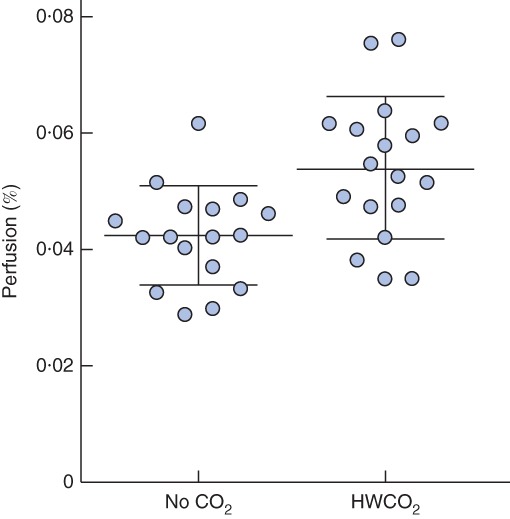

Core body temperature was regulated only in the HWCO2 group (P < 0·001), despite the use of a warming pad in all animals (Fig. 2). Anaesthesia lowered heart rate comparably in both groups, from the reported normal range of 630 beats/min9 to a mean(s.d.) of 409(39) and 404(33) beats/min in the control (no carbon dioxide) and HWCO2 groups respectively. Percentage perfusion at the paw was significantly higher in the HWCO2 group (0·054(0·012) versus 0·042(0·008) per cent; P = 0·002) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

Core temperature monitoring over time in control (no carbon dioxide) and humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) groups (18 in each group). Normal body temperature range for mice shown by dotted lines. Values are mean(s.d.). P < 0·001 for mean temperature of both cohorts (2‐way ANOVA)

Figure 3.

Percentage perfusion at the mouse paw in control (no carbon dioxide) and humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) groups (18 in each group). Values are plotted for each animal and mean(s.d.) values are also shown. P = 0·002 (2‐way t test)

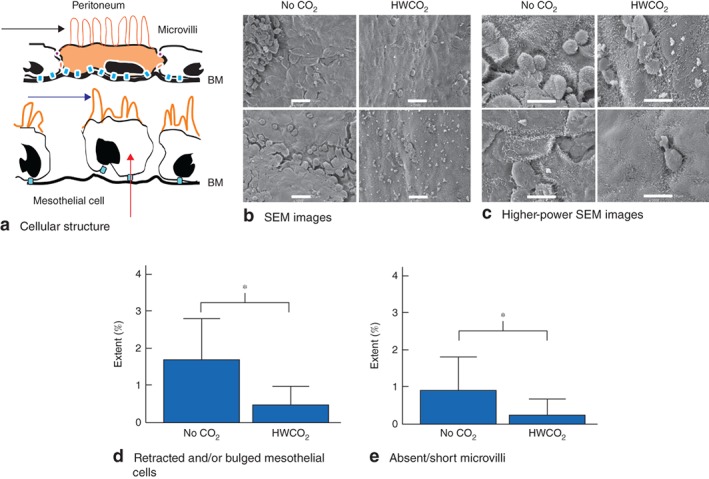

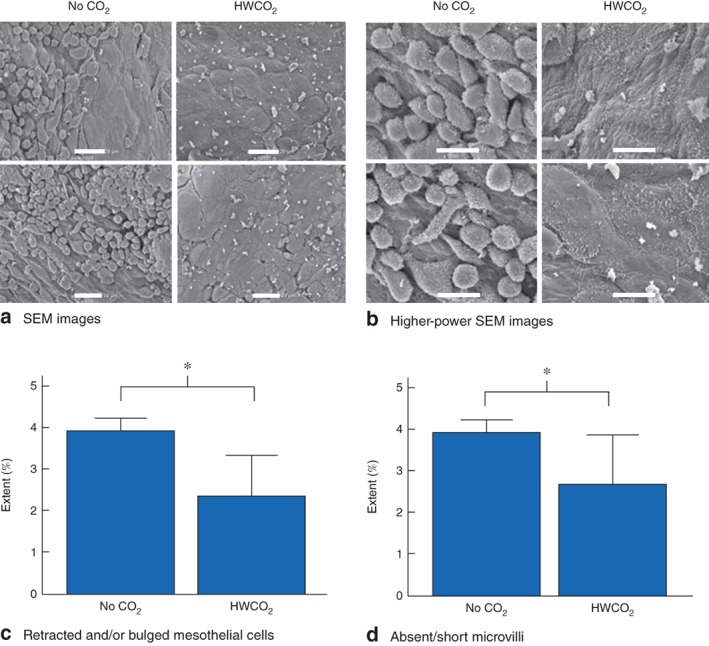

During the procedure, physical trauma was delivered to one side of the exposed peritoneal wall. Tissue was collected and processed for IHC analysis and scanning electron microscopy 24 h and 10 days after laparotomy. The integrity of mesothelial cells was evaluated in terms of microvilli persistence and length, along with cell bulging or delamination (Fig. 4 a). Scanning electron microscopy identified more extensive microvilli damage and cellular bulging at 24 h after surgery in the control group (Fig. 4 b,c). Quantitative analysis of the extent of cellular retraction and/or bulging and microvillus damage or loss revealed that HWCO2 afforded significant protection (P = 0·009 and P = 0·035 respectively) (Fig. 4 d,e).

Figure 4.

a Illustration depicting a normal peritoneal cell with cellular junctions (orange and blue) along with normal microvilli (black arrow). Damaged microvilli (blue arrow) and delaminating/bulging mesothelial cells (red arrow) are also illustrated, and exposure of the basement membrane (BM). b Representative scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images of peritoneal surface at 24 h after laparotomy in control (no carbon dioxide) and humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) groups (scale bar 20 μm). c Higher‐power SEM images in both groups; cell bulging was apparent in the control group (scale bar 10 μm). d,e Quantification of retracted and/or bulged mesothelial cells (d) and structural defects in microvilli (e). Values are mean(s.d.) extent of damage (9 per group). *P < 0·050 (2‐way t test)

Tissue damage following simulated surgical trauma

Examining the peritoneal tissue trauma indicated that the extent of cellular retraction and/or bulging and microvillus damage or loss was significantly reduced in the HWCO2 group (P < 0·001 and P = 0·011 respectively), suggesting that this intervention was protective at 24 h (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of humidified–warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) on simulated surgery damage at 24 h after laparotomy. a Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images from both groups; mesothelial bulging and delamination was reduced by the use of HWCO2 (scale bar 20 μm). b Higher‐magnification SEM images of peritoneal surface in both groups (scale bar 10 μm). c,d Quantification of retracted and/or bulged mesothelial cells (c) and structural defects in microvilli (d). Values are mean(s.d.) (9 per group). *P < 0·050 (2‐way t test)

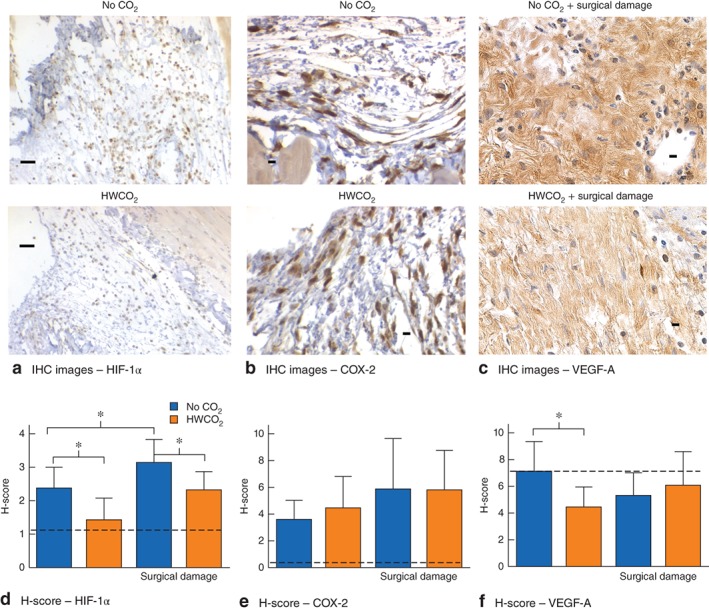

Peritoneal hypoxia

HIF‐1α nuclear staining was reduced significantly by the use of HWCO2 in undamaged as well as damaged peritoneal sites (Fig 6 a,d). An additional inflammatory marker, COX‐2, was also examined, but no differences were observed between groups or treatments (Fig. 6 b,e). In contrast, in the group of mice not subjected to tissue damage, HWCO2 appeared to reduce the level of VEGF‐A expression (Fig. 6 f).

Figure 6.

Effect of humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) on markers of hypoxia at 24 h after laparotomy. a–c Matched immunohistochemical (IHC) images showing expression of nuclear hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) 1α (a) and cyclo‐oxygenase (COX) 2 expression (b) in the peritoneum, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A staining of damaged peritoneum (c) in control (no carbon dioxide) and HWCO2 groups (scale bar 50 μm). d–f Histological scores (H‐scores) for IHC staining of HIF‐1α, (d) COX‐2 (e) and VEGF‐A (f). Dotted lines indicate basal expression of each marker in mice subjected to anaesthesia but no surgery. Values are mean(s.d.) (9 per group). *P < 0·050 (2‐way t test)

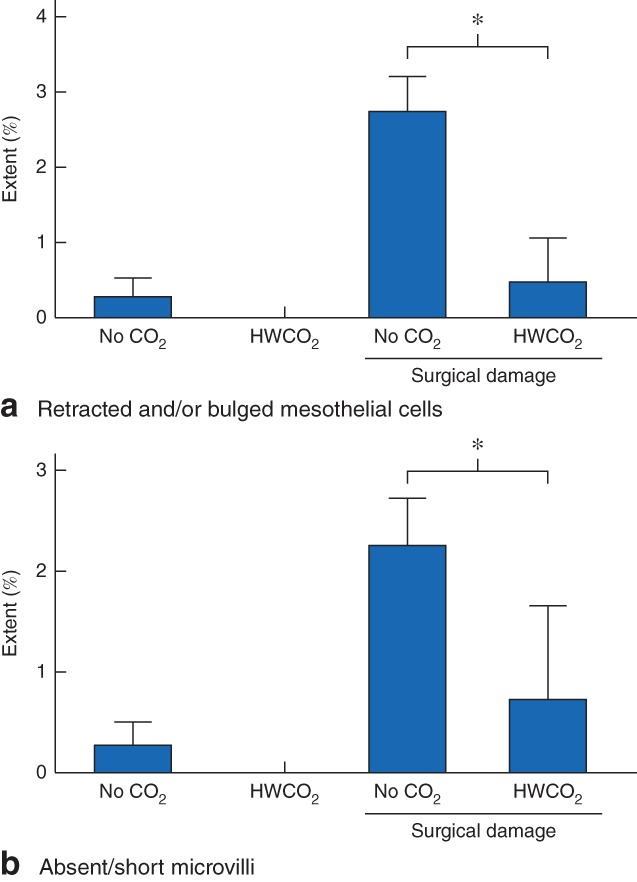

Longer‐term effect of humidified‐warm carbon dioxide

To evaluate the longer‐term effects of HWCO2 on the peritoneum, mice were killed 10 days after laparotomy. The tissue damage evident on the day after operation in all mice not subjected to simulated surgical damage was fully repaired by day 10 (Fig. 7). In contrast, surgical damage remained measurable on day 10. As was the case at 24 h after laparotomy, the use of HWCO2 was associated with less damage 10 days after simulation of surgical trauma (P = 0·001 for cellular retraction and/or bulging, P = 0·032 for absent/short microvilli).

Figure 7.

Sustained tissue changes assessed at 10 days after laparotomy in control (no carbon dioxide) and humidified‐warm carbon dioxide (HWCO2) groups in the absence or presence of damage caused by simulated surgery: a retracted and/or bulged mesothelial cells and b structural defects in microvilli. Values are mean(s.d.) (9 per group). *P < 0·050 (2‐way t test)

Simulated surgery damage and metastatic tumour formation

To evaluate the influence of HWCO2 on the potential of colorectal cancer cells to establish tumours, 1000 CT26 colorectal cancer cells were delivered into the peritoneum immediately before wound closure. In the presence of simulated surgery damage, both groups of mice had a substantial tumour burden by day 10, with no significant differences (Fig. S1, supporting information). No tumours were evident on the undamaged peritoneal walls following laparotomy, in contrast to previous findings with dry‐cold carbon dioxide insufflation employed for laparoscopy5.

Discussion

Hydrated peritoneal surfaces serve as sites of fluid, nutrient and gas exchange. Indeed, these properties underpin the effect of peritoneal dialysis10. Similarly, when visceral tissue is exposed to ambient atmosphere, as during laparotomy, moisture loss is readily evident as diminished reflection of light, including changes in colour and tissue stickiness. At the cellular level, the parietal peritoneum mesothelial cells are stressed, whereby their microvilli are damaged or lost. Eventually the cells begin to delaminate, exposing the extracellular basement membrane (ECM), with which normal mesothelial cells are in intimate contact11, 12. In the context of laparoscopy, this cellular damage is exacerbated by exposure to dry‐cold carbon dioxide‐mediated insufflation. Use of HWCO2 for insufflation affords protection from such desiccation2, 5, 13, 14. By adapting this concept to the delivery of HWCO2 into an open abdominal cavity, significant protection from the effects of passive desiccation could be achieved.

It is recognized that damaged peritoneum can serve as an ideal site for cancer cell attachment and tumour formation5, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. The mechanism(s) that drive this propensity for tumorigenesis include exposure of the ECM, and the induction of inflammatory processes demonstrable by the expression of COX‐2 and VEGF‐A5. The loss of mesothelial cell integrity additionally affects oxygen tension during laparotomy7, and the robust marker of hypoxia, HIF‐1α, was induced during laparotomy in the present study. HIF‐1α was evident 1 day after open surgery, indicating a persistence of the signals that induce the expression of, and/or lead to, HIF‐1α protein stabilization20. More generally, the extent of damage and induction of inflammation measured here would appear to be less for a 1‐h laparotomy procedure than for the same duration of laparoscopy involving dry‐cold carbon dioxide‐mediated insufflation reported previously5. The use of HWCO2 in both surgical contexts consistently led to reduced tissue damage and inflammation.

HIF‐1α is strongly associated with tumorigenic events; it acts to facilitate the transcription of a range of genes that encode proteins responsible for increased tumour chemoresistance, inflammation, immunosuppression and escape from apoptosis20. The simple intervention of delivering HWCO2 ameliorated the induction of hypoxia and inflammation and, more compellingly, the persistence of simulated surgical damage was reduced at the peritoneum. Perhaps this was because the physical tissue damage was not exacerbated by further tissue desiccation. These differences are of particular interest considering that mice typically have very robust wound repair capacity. Nevertheless, the benefits of reducing desiccation were measurable to at least 10 days after laparotomy and could explain how this intervention appears to reduce tissue adhesions, which are influenced by the presence of persistent tissue damage21, 22, 23, 24.

Others25 have examined the role of HIF‐1α expression by tumour cells on peritoneal metastasis, whereas here the focus was on the expression of HIF‐1α in the peritoneum. Exposure of the ECM by delaminating mesothelial cells was associated with increased HIF‐1α expression, and it is to the ECM that the colorectal cancer cells adhere. Based on gene expression profiling, the mouse CT26 colorectal cancer cell line represents the mesenchymal subtype26 that corresponds to 23 per cent of human colorectal cancer cells, with its predominant transforming growth factor β activation gene expression signature, stromal invasion, and propensity to drive angiogenesis27.

The present study suggests that HWCO2 is insufficient to block tumour formation where cancer cells have immediate access to this damage. However, where the cancer cell burden is minimal, the interval of time during which tissue repair might be achieved may be important.

This study was carried out in mice and thus has obvious limitations when considering translation into patients. For instance, passive air flow alone was employed in the control group, which is likely to generate less desiccation than that associated with active laminar flow systems in use in modern operating theatres. The duration of surgery was only 1 h, whereas most laparotomy procedures are longer. Others28 have explored the role of HWCO2 in the context of colorectal cancer surgery and have not found a compelling case for its use in terms of cancer outcomes, but the numbers were small and the types of surgical procedure varied. These caveats aside, the peritoneum of the mouse is very similar to that in humans, and all show the same propensity to manifest tissue damage associated with inevitable desiccation during surgery. The events that can be measured in the tissue by IHC analysis and scanning electron microscopy are consistent across these species. Given these findings, the potential benefits of reducing peritoneal tissue damage while increasing the rate of tissue repair by employing the simple procedure of HWCO2 delivery in both closed and open surgery should be considered.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Evaluation of tumour formation at 10 days after abdominal delivery of CT26 cancer cells, in mice subjected to humidified‐warm carbon dioxide and controls. a (i) peritoneal tumour formation indicated by the white arrow at the wound bound by sutures and surgical clips at the surgical incision site at 10 days post‐delivery of 1000 CT26 cells into the peritoneum, (ii) cartoon showing location of central incision and introduced damage site distal to the incision, (iii) detection of CherryRed fluorescence at the incision site and (iv) the surgical damage site, b tumour burden quantified by CherryRed fluorescence in both cohorts of mice and yellow arrow at the site of surgical damage (two way t‐test; means +/‐ SD)

Acknowledgements

S.C. and S.S. contributed equally to this study. This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia, Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre Foundation and the Epworth Research Foundation. Special thanks to J. Hiller, who was instrumental in optimizing the animal anaesthesia conditions required for the open surgery procedures employed in this study.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Dharan S, Pittet D. Environmental controls in operating theatres. J Hosp Infect 2002; 51: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Persson M, van der Linden J. Intraoperative field flooding with warm humidified CO2 may help to prevent adhesion formation after open surgery. Med Hypotheses 2009; 73: 521–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaudasch G, Schempp P, Skierski P, Turner E. [The effect of convection warming during abdominal surgery on the early postoperative heat balance.] Anaesthesist 1996; 45: 1075–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lindic J, Psenicnik M, Bren A, Gucek A, Ferluga D, Kveder R. The morphology of parietal peritoneum: a scanning electron micrograph study. Adv Perit Dial 1993; 9: 36–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carpinteri S, Sampurno S, Bernardi MP, Germann M, Malaterre J, Heriot A et al Peritoneal tumorigenesis and inflammation are ameliorated by humidified‐warm carbon dioxide insufflation in the mouse. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22(Suppl 3): 1540–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kerscher AG, Chua TC, Gasser M, Maeder U, Kunzmann V, Isbert C et al Impact of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the disease history of colorectal cancer management: a longitudinal experience of 2406 patients over two decades. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 1432–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marshall JK, Lindner P, Tait N, Maddocks T, Riepsamen A, van der Linden J. Intra‐operative tissue oxygen tension is increased by local insufflation of humidified‐warm CO2 during open abdominal surgery in a rat model. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0122838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corbett TH, Griswold DP Jr, Roberts BJ, Peckham JC, Schabel FM Jr. Tumor induction relationships in development of transplantable cancers of the colon in mice for chemotherapy assays, with a note on carcinogen structure. Cancer Res 1975; 35: 2434–2439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. The Staff of the Jackson Laboratory . Biology of the Laboratory Mouse. Blakiston Division, McGraw‐Hill: New York, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grassmann A, Gioberge S, Moeller S, Brown G. ESRD patients in 2004: global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2005; 20: 2587–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fang W, Qian JQ, ZY Yu, Chen SS. Morphological changes of the peritoneum in peritoneal dialysis patients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2004; 117: 862–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. von Ruhland CJ, Newman GR, Topley N, Williams JD. Can artifact mimic the pathology of the peritoneal mesothelium? Perit Dial Int 2003; 23: 428–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Binda MM, Molinas CR, Hansen P, Koninckx PR. Effect of desiccation and temperature during laparoscopy on adhesion formation in mice. Fertil Steril 2006; 86: 166–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Binda MM. Humidification during laparoscopic surgery: overview of the clinical benefits of using humidified gas during laparoscopic surgery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2015; 292: 955–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Azuar AS, Matsuzaki S, Darcha C, Déchelotte PJ, Pouly JL, Mage G et al Impact of surgical peritoneal environment on postoperative tumor growth and dissemination in a preimplanted tumor model. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 1733–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsuzaki S, Bourdel N, Darcha C, Déchelotte PJ, Bazin JE, Pouly JL et al Molecular mechanisms underlying postoperative peritoneal tumor dissemination may differ between a laparotomy and carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum: a syngeneic mouse model with controlled respiratory support. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nduka CC, Puttick M, Coates P, Yong L, Peck D, Darzi A. Intraperitoneal hypothermia during surgery enhances postoperative tumor growth. Surg Endosc 2002; 16: 611–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van den Tol PM, van Rossen EE, van Eijck CH, Bonthuis F, Marquet RL, Jeekel H. Reduction of peritoneal trauma by using nonsurgical gauze leads to less implantation metastasis of spilled tumor cells. Ann Surg 1998; 227: 242–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Volz J, Koster S, Spacek Z, Paweletz N. The influence of pneumoperitoneum used in laparoscopic surgery on an intraabdominal tumor growth. Cancer 1999; 86: 770–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. LaGory EL, Giaccia AJ. The ever‐expanding role of HIF in tumour and stromal biology. Nat Cell Biol 2016; 18: 356–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Binda MM, Molinas CR, Mailova K, Koninckx PR. Effect of temperature upon adhesion formation in a laparoscopic mouse model. Hum Reprod 2004; 19: 2626–2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Molinas CR, Binda MM, Manavella GD, Koninckx PR. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery: what do we know about the role of the peritoneal environment? Facts Views Vis Obgyn 2010; 2: 149–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Molinas CR, Campo R, Dewerchin M, Eriksson U, Carmeliet P, Koninckx PR. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor in basal adhesion formation and in carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum‐enhanced adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in transgenic mice. Fertil Steril 2003; 80(Suppl 2): 803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng Y, Zheng M, Ye Q, Chen X, Yu B, Liu B. Heated and humidified CO2 prevents hypothermia, peritoneal injury, and intra‐abdominal adhesions during prolonged laparoscopic insufflations. J Surg Res 2009; 151: 40–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miyake S, Kitajima Y, Nakamura J, Kai K, Yanagihara K, Tanaka T et al HIF‐1alpha is a crucial factor in the development of peritoneal dissemination via natural metastatic routes in scirrhous gastric cancer. Int J Oncol 2013; 43: 1431–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castle JC, Loewer M, Boegel S, de Graaf J, Bender C, Tadmor AD et al Immunomic, genomic and transcriptomic characterization of CT26 colorectal carcinoma. BMC Genomics 2014; 15: 190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reynies A, Schlicker A, Soneson C et al The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21: 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sammour T, Kahokehr A, Hayes J, Hulme‐Moir M, Hill AG. Warming and humidification of insufflation carbon dioxide in laparoscopic colonic surgery: a double‐blinded randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 1024–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Evaluation of tumour formation at 10 days after abdominal delivery of CT26 cancer cells, in mice subjected to humidified‐warm carbon dioxide and controls. a (i) peritoneal tumour formation indicated by the white arrow at the wound bound by sutures and surgical clips at the surgical incision site at 10 days post‐delivery of 1000 CT26 cells into the peritoneum, (ii) cartoon showing location of central incision and introduced damage site distal to the incision, (iii) detection of CherryRed fluorescence at the incision site and (iv) the surgical damage site, b tumour burden quantified by CherryRed fluorescence in both cohorts of mice and yellow arrow at the site of surgical damage (two way t‐test; means +/‐ SD)