Abstract

Introduction

Although patient safety has improved steadily, harm remains a substantial global challenge. Additionally, safety needs to be ensured not only in hospitals but also across the continuum of care. Better understanding of the complex cognitive factors influencing health care–related decisions and organizational cultures could lead to more rational approaches, and thereby to further improvement.

Hypothesis

A model integrating the concepts underlying Reason's Swiss cheese theory and the cognitive‐affective biases plus cascade could advance the understanding of cognitive‐affective processes that underlie decisions and organizational cultures across the continuum of care.

Methods

Thematic analysis, qualitative information from several sources being used to support argumentation.

Discussion

Complex covert cognitive phenomena underlie decisions influencing health care. In the integrated model, the Swiss cheese slices represent dynamic cognitive‐affective (mental) gates: Reason's successive layers of defence. Like firewalls and antivirus programs, cognitive‐affective gates normally allow the passage of rational decisions but block or counter unsounds ones. Gates can be breached (ie, holes created) at one or more levels of organizations, teams, and individuals, by (1) any element of cognitive‐affective biases plus (conflicts of interest and cognitive biases being the best studied) and (2) other potential error‐provoking factors. Conversely, flawed decisions can be blocked and consequences minimized; for example, by addressing cognitive biases plus and error‐provoking factors, and being constantly mindful. Informed shared decision making is a neglected but critical layer of defence (cognitive‐affective gate). The integrated model can be custom tailored to specific situations, and the underlying principles applied to all methods for improving safety. The model may also provide a framework for developing and evaluating strategies to optimize organizational cultures and decisions.

Limitations

The concept is abstract, the model is virtual, and the best supportive evidence is qualitative and indirect.

Conclusions

The proposed model may help enhance rational decision making across the continuum of care, thereby improving patient safety globally.

Keywords: cognitive biases, evidence‐based medicine, gate model, healthcare, organizations, patient safety, rational decision making, cognition

To err is human (Alexander Pope)

Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability (Sir William Osler)

1. INTRODUCTION

Patient safety has been defined variously. The definition we have chosen for this paper is “prevention of (healthcare‐associated) harm caused by errors of commission or omission”1; the harm should have been preventable or predictable with the knowledge available at that time. The definition encompasses the consequences of overdiagnosis and overuse or underuse of health care resources.2, 3 Patient safety is person‐centred, and “first do no harm (primum non nocere)” is a fundamental principle of bioethics.4 Harm from medical care continues to impose a substantial global burden.5

The systematic study of patient safety, even in hospitals, is recent. Current strategies on patient safety are generally process driven and hospital based, and not person centred across the life span.6 Hospital stays have steadily decreased for both medical conditions and after surgical procedures; simultaneously and increasingly, complex care is now being provided on an out‐patient basis.4, 7, 8, 9 Gaps in the continuity of care are an important cause of morbidity and mortality.6 Therefore, systematic studies of patient safety and quality of care measures should now also focus on care provided outside hospitals.6, 8

The 2015 “Free from Harm” report highlighted the progress that had been made in minimizing harm; at the same time, the authors drew attention to the complexities underlying errors that remained unaddressed and made several recommendations to rectify deficiencies.8, 9 Those pertinent to our analysis are (1) a systems approach that would require “active involvement of every player (italics ours) in the health care system,” (2) coordination and collaboration “across organizations,” (3) promoting “safety culture,” and (4) ensuring safety not just in hospitals but across the entire continuum of care including long‐term facilities and patients' homes.6, 8 The cognitive roots of decision making and diagnostic errors have also been targeted for attention.1, 10, 11, 12

These suggestions echo many of those made earlier by Reason.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 A conceptual framework to implement them successfully is urgently needed because fiscal and ideological challenges to privately and publicly funded health care in many countries19, 20, 21, 22, 23 may not only derail improvement but also enhance the risk of error. In February 2017, Sir Robert Francis QC warned that the National Health Service (NHS, United Kingdom) was facing an “existential crisis,” and a repeat of the Mid Staffordshire Hospital care scandal was inevitable.24

2. HYPOTHESIS

Complex cognitive processes underlie decisions, behaviours, and cultures of health care–related organizations, teams, and individuals. A model that integrates the concepts underlying Reason's Swiss cheese theory and the cognitive biases plus cascade15, 25, 26 may help us understand the complexities and also provide an evidence‐informed approach for identifying potential solutions to minimize deficiencies.1, 8, 10, 11

3. METHODS

This thematic analysis27 is in part an overview of earlier reviews.25, 26, 28 Additionally, previously described strategies28 were used to update references and also retrieve articles on patient safety and the Swiss cheese model (SCM). The search was restricted to the English language. The potential for selection bias in the references chosen for inclusion is acknowledged.

3.1. Use of terms and quotation marks

Words and sentences quoted verbatim to avoid the bias of paraphrasing are placed in “double” quotation marks. Italics are used, generally the first time, words or terms with ambiguous meanings are used in a specific context. Thus, Reason is only used as a proper noun.

Unless, otherwise specified, health care encompasses that of both the individual and population across the continuum of care. Diagnoses and complex health care decisions are now being made or influenced by professionals other than doctors, and provision of health care is a multidisciplinary effort. Therefore, professionals refer to health care practitioners, allied health care professionals, and health care administrators. In the present context, individuals refer not only to professionals but also to all others who have the potential to influence patient safety; examples of the latter include politicians and persons associated with agencies regulating health care.

There are several definitions of error and many ways in which errors can be classified; Reason also distinguished between errors and violations while incorporating both under “unsafe acts.”14, 18 In this paper, errors encompass acts of commission and omission,1 ie, all “unsafe acts.”

Section 4 lays the foundations for the integrated model.

4. BACKGROUND

4.1. The Swiss cheese model

Reason's study of “human error” began in the 1970s with an initial focus on industrial accidents.29 He continually revised and updated his concepts, including those pertinent to the SCM (Figure 1), over the next 40 years.13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 29, 30, 31, 32 He suggested that the knowledge gained from the study of industrial practices and accidents could be adapted to health care.14 At the same time, he warned that health care was far more complex than any industry, the complexity enhancing the potential for errors while increasing the challenges for avoiding them.16, 32, 33 Reason's warning has been reinforced recently.33

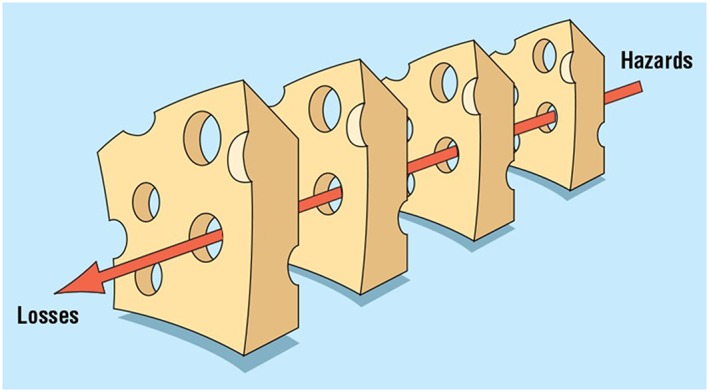

Figure 1.

Reason's 1997 to 2008 version of the Swiss cheese model (SCM). The original legend for this figure reads as follows: “The Swiss cheese model of how defences, barriers, and safeguards may be penetrated by an accident trajectory.” The figure is from Reason15 and was provided by Mr John Mayor, Chief Production Manager the BMJ, and reproduced with permission from the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. To our knowledge, Reason has not published any further revisions to the figure

There have been several criticisms of the SCM: (1) too simplistic, (2) nonspecific without explicit definitions for the slices and holes, (3) static portrait of complex systems, (4) potentially open to differing interpretations, and (5) focusing unduly on systemic and organizational factors rather than on the errors of individuals.31, 34, 35, 36, 37 Reason cautioned that the model was a “symbolic simplification that should not be taken literally” and emphasized that the SCM was a generic tool meant to be custom tailored to specific situations18, 31; an example of such use is shown in Figure 2.38 He also acknowledged that the SCM was only one of many for studying “accidents.” The SCM has been used in a variety of medical settings17, 18, 31, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 and has also been the basis for other models of “incident causation.”31, 36

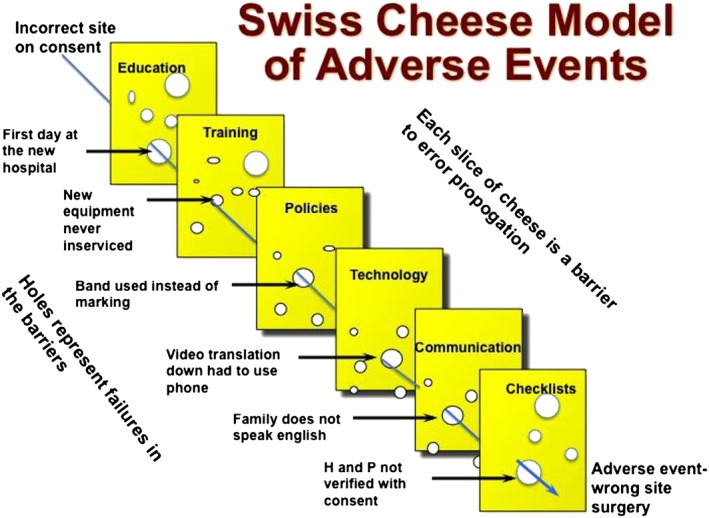

Figure 2.

An example to show how the generic Swiss cheese model can be adapted to specific situations—in this case a surgical error. For details please refer to Stein and Heiss.38 “H and P” means history and physical examination. In addition, the figure demonstrates both (1) the barriers (cognitive‐affective gates) to error propagation, ie, gating the holes, and (2) the error catalyzing factors that result in holes or breaching of the cognitive‐affective gates (please see text). Reproduced with permission of Elsevier. Tables 1 and 2 provide complementary information

4.2. The systems approach

A systems approach requires not only an assessment of the culture, policies, and all the individual components of an organization but also the external influences on them.15 Reason suggested that many errors committed by individuals had their roots in such “upstream” influences.18 Automation, an increasing component of all systems including health care, may simplify tasks but also add to the complexity of problem‐solving and cognitive burden when something goes wrong.14, 18, 29 Highly reliable and resilient organizations focus on the entire system, support the workforce, and facilitate a culture of “intelligent wariness.”15

Health care professionals are generally considered to be the last line of defence in the health care system.16, 18, 36 Reason warned that the person‐focused approach alone “has serious shortcomings and is ill suited” to medical errors, arguing that “the pursuit of greater safety is seriously impeded” if the “error provoking properties within the system at large” were not addressed15: The “Free from Harm” document confirms that effective systems methods have not been adopted by many health care influencing organizations.8, 9

4.3. Organizations influencing patient safety

Patient safety can be positively or negatively influenced by several “upstream” organizations in differing ways and at different points on the continuum of care; these organizations have complex, at times hierarchical, associations, and frequently function in silos17; the administration and funding of health care services and delivery have also become increasingly complicated in many countries.14, 17, 22, 23, 28, 45, 46 The end result is fragmentation of health care,3, 4, 22, 23, 46, 47 which is most apparent in nonhospital care4, 7: Discontinuity of care is a risk to patient safety.6 Additionally, several organizations influence the quality of evidence that informs person‐centred health care25, 26, 28: Quality of evidence and the applicability to the individual are also important determinants of patient safety.25, 26, 28, 48, 49, 50

Any listing or discussion of all the possible organizations influencing patient safety is beyond the scope of this paper and will be the subject of a separate one. In the present context, organization is a functional concept referring to an association of people with a shared culture: Goals, vision, views, and/or mission; subcultures can exist within teams and departments of large organizations. Individuals in an organization may or may not be employees, and frequently, there is a hierarchy of influence and/or authority (Figure 3).25, 26, 28, 51 Organizational cultures can be healthy or unhealthy.29, 51, 52, 53 Organizations, teams, and professionals can have a positive or negative effect on patient safety, complex cognitive processes being involved.11, 25, 26, 28, 48, 54

Figure 3.

Simplified representation of the hierarchical influences on patient safety

4.4. Cognition

Cognition is the seamless integration of mental processes by which the brain transforms, stores, and uses internal and external inputs. The integration is dependent upon an intricate matrix of neural networks involving not only the cerebral hemispheres but also likely the entire brain, including the cerebellum.55, 56, 57 Functionally, cognition occurs relatively harmoniously at the unconscious and conscious levels. The former corresponds to system 1 (“thinking fast”) and the latter to system 2 (“thinking slow”), ie, the dual‐process system; we function mainly in the quicker more energy‐efficient system 1 (autopilot) mode and do so correctly most of the time; errors likely arise from both systems, although system 1 has generally been considered to be more error‐prone.18, 54, 58, 59, 60, 61

Table 1 lists some factors likely to catalyze error: Frequently, these co‐occur, and all are common in health care.7, 14, 16, 17, 18, 40, 41, 42, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 Decisions can also be influenced by a complex constellation of emotions created by workplace cultures, the nature of the task, and endogenous or exogenous psychological factors affecting health care providers.65, 68 Chronic exposure to adverse influences can lead to gradual burnout, further compromising decision making.68 Patient‐related factors (Table 1) are also important.69, 70 The contribution of psychological factors to safety is understudied and generally overlooked.65, 68, 69 Measures to prevent and address all these factors can improve safety.

Table 1.

Examples of error‐catalyzing factors across the continuum of care

| Organization‐ or team‐related factors |

| 1. Unhealthy cultures |

| 2. Poor communication (written, verbal) including silo mentality within or between one or more levels of care |

| 3. Inadequate resources especially staffing, equipment, etc (includes access to drugs, equipment, and tests) |

| 4. Time and energy spent in having to access needed services (beds, tests, etc) because of system inefficiencies or culture |

| 5. Failure of organization or team to promote and practice person‐ and family‐centred health care and informed shared decision making |

| 6. Failure to seek an independent reliable opinion (outside view) when the situation warrants it |

| Individual‐related factors (some are secondary to upstream organizational factors) |

| 1. Suboptimal communication with others in the system |

| 2. Knowledge‐experience‐skill set |

| (i) Knowledge‐deficit, inexperience, or poor skill sets related to level of training or poor continuing education |

| (ii) Specific knowledge deficits concerning probability estimates |

| (iii) Inexperience/knowledge‐deficit related to novel situation (has not encountered situation before; experts in the field are not exempt) |

| (iv) Poor skills (especially surgical, emergency procedures, etc) |

| 3. Unpredictable and changing situation (eg, critically ill patients, unexpected adverse events during surgery, and equipment malfunction) |

| 4. Failure to seek an independent reliable opinion (outside view) when the situation warrants it |

| 5. Time and concentration factors |

| (i) Haste (may be due to resource limitations or individual has the time but hurries through task for other reasons) |

| (ii) Work overload; often associated with inadequate staffing: both result in time constraints for each specific task |

| (iii) Interruptions or distractions during task (self‐created or caused by others) |

| 6. Cognitive‐affective |

| (i) Impact of biases on judgement and decision making |

| (ii) Sleep deprivation/fatigue |

| (iiia) Adverse exogenous (related to the environment) and endogenous (individual‐specific) psychological states; latter includes dysphoria, personal life stressors, and burnout |

| (iiib) The impaired individual |

| (iv) Violations of safe practices |

| (v) Cognitive overload: usually an end result of a combination of several factors listed in this table |

| 7. Failure to adequately communicate with patients and their caregivers or engage in informed shared decision making |

| Patient‐related factors |

| 1. Communication challenges (eg, language barrier and cognitive dysfunction) |

| 2. Adherence (incorporates compliance and concordance) |

| 3. Cognitive‐affective biases (plus) of patients and caregivers can influence personal health care decisions |

| 4. Biases of systems, organizations, and health care providers against those who are economically disadvantaged, from minority groups or because of patient's history. Biases may also be related to age, gender, and patient's medical or psychological state (eg, obesity and psychiatric or psychological disorders) |

Typically, several factors co‐occur. These factors create holes in the Swiss cheese and/or may cause holes to align in several successive layers of defence: We refer to these phenomena as “breaching of the cognitive‐affective gates” (discussed in the text). Authors' compilation from several references cited in the text. The list is not meant to be all‐inclusive.

4.5. Cognitive biases plus (+)

The term “cognitive biases plus (+)” was proposed for the following reasons25, 26, 28: (1) cognition is inextricably linked, both neurally and functionally, with emotion; (2) cognitive biases, conflicts of interest (CoIs), ethical violations, and fallacies frequently co‐occur in various combinations to compromise rational thinking, discourse, and actions; (3) all have complex cognitive underpinnings; (4) some are evolutionary; and (5) all are likely influenced by family, professional, organizational, and prevalent social cultures. Thus, plus emphasizes that cognitive biases are not the only explanation for flawed decisions,13, 14, 15, 30, 61, 71, 72, 73 the factors listed in Table 1 being among them.

The inseparable link between cognition and emotion28, 65, 66, 68 suggests that the term cognitive‐affective biases may be more accurate than cognitive biases alone; cognitive‐affective biases incorporate the concepts of both cognitive and affective dispositions to respond.74 Currently, cognitive‐affective biases and CoIs are likely the best studied elements of cognitive‐affective biases plus. All individuals including patients and families, teams, and organizations are susceptible to varying degrees of cognitive‐affective biases,11, 28, 54 and potentially also to CoIs.

A complex mix of cognitive‐affective processes is involved in creating healthy or unhealthy team and organizational cultures. Pockets of good and bad team cultures can exist within large organizations. Blind spot bias may be an important catalyst for toxic team and organizational cultures.75

4.6. Cognitive‐affective biases plus (+) cascade

In biology, cascade refers to a process that once started proceeds stepwise to its full, seemingly inevitable conclusion76; biological cascades can be physiological or pathological, both being catalyzed by either endogenous or exogenous factors. Conversely, pathological cascades may be preventable or cut short. Recognized examples include metabolic, complement, and coagulation cascades.

The cognitive (‐affective) biases plus cascade detailed elsewhere25, 26 is a simplified representation of a confluence of presumed primarily unconscious, multiple interlinked cognitive‐affective processes.

Primary catalysts for the cascade are CoIs: Frequently, financial and nonfinancial interests co‐occur.28, 77 Some argue that nonfinancial interests are not CoIs,78 while others differ: All agree that nonfinancial interests can also bias opinion.50, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81 CoIs catalyze self‐serving bias, a strong innate evolutionary trait; self‐serving bias risks self‐deception and rationalization, which in turn can catalyze ethical violations.25, 26, 28, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86 The cascade is reinforced by other elements of cognitive‐affective biases plus. Like many biological circuits, these circuits are potentially reinforcing.

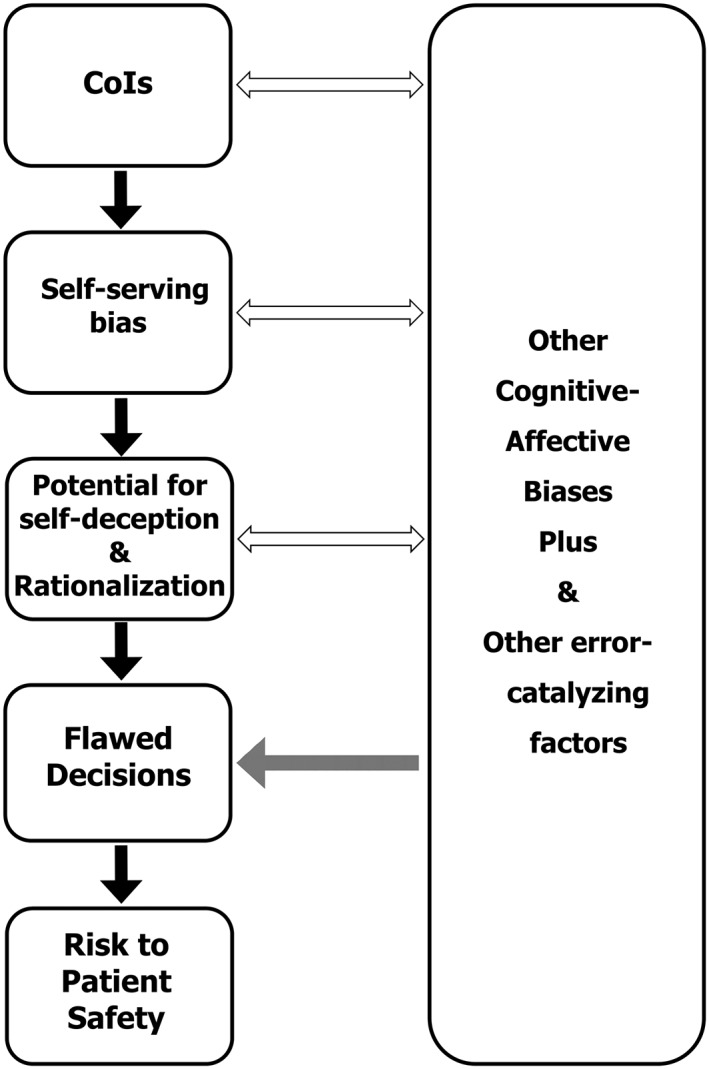

In some clinical situations, there may be no apparent CoI and cognitive‐affective biases, and the factors listed in Table 1 may be the principal catalysts for potential errors, often through a chain of cascading events and/or actions.76 Self‐deception and rationalization likely play an important role in the cascade triggered by CoIs, cognitive‐affective biases, and other elements of cognitive‐affective biases plus. Without safeguards or timely interventions, such cascades can compromise patient safety (Figure 4).76

Figure 4.

Simplified representation of the putative cognitive‐affective biases plus cascade. “CoIs” means conflicts of interest. Please see the text for details. Bidirectional arrows represent potential bidirectional reinforcing influences. Solid unidirectional arrows portray predominant unidirectional influences. Grey unidirectional arrow suggests possibility of a direct unidirectional influence. Please see Table 1 for list of error‐catalyzing factors and Table 2 for ways to prevent, minimize, or reverse their consequences. The boxes are convenient envelopes for the text and their relative sizes have no significance. This figure has been substantially revised from figure 3 of Seshia et al25 (publisher: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.) and figure 1 of Seshia et al26 (publisher: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd). Permission from both publishers obtained.

5. GATING THE HOLES IN THE SWISS CHEESE: THE INTEGRATED MODEL

Reason revised his model several times.13, 15, 18, 29, 30, 31 He considered correct performance and error to be “two sides of the same cognitive balance sheet”13; his concepts encompassed the notion of resiliency intrinsic to high reliability organizations, a philosophy also reflected in the safety‐II paradigm.36, 87 Our proposed model integrates current concepts in the cognitive‐behavioural sciences explicitly into the SCM.

Defences against error are key in Reason's system approach; some safeguards are technological but most if not all ultimately depend on individuals.15, 18, 29, 30 He described the cheese slices as “successive layers of defences, barriers, and safeguards” throughout the health care system. We suggest that each layer (slice) can be conceptualized as a (human dependent) dynamic cognitive‐affective gate functioning like a firewall and antivirus program; the gate allows correct decisions to pass through while filtering out or countering errors.

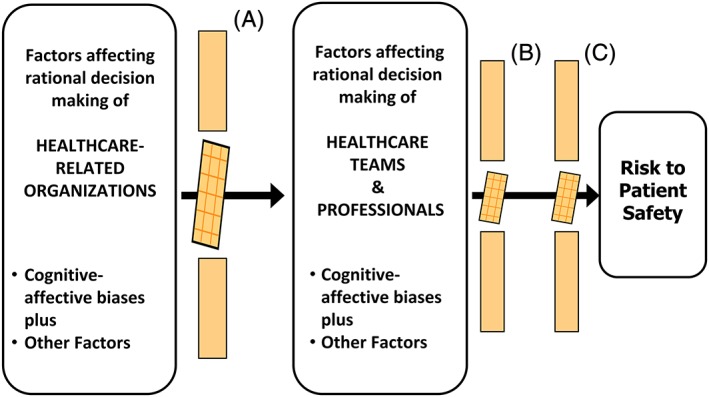

At a macro level, each slice (gate) represents a defensive layer at the stage of the organization, team, and individual (Figure 5). At a micro level, there may be several steps in the decision‐making process of each organization, team, or individual where such gating may occur or additional gates (reinforcements) may be activated.

Figure 5.

Simplified representation of the proposed integrated cognitive‐affective–gated Swiss cheese model. The middle segment of each “Swiss cheese” layer represents breaching of the cognitive‐affective gate: The holes in the Swiss cheese. Slice A, breach at the level of upstream organizational influences, for example, by (1) unsound decisions made at higher organizational levels or (2) dissemination of erroneous information by those with influence or in positions of authority. Slice B, breach at level of health care professionals, for example, by (1) sleep deprivation or (2) inadequate knowledge. Slice C, breach at the level of patients and caregivers, for example, by (1) suboptimal shared decision making or (2) nonadherence. Please see text for details. Figure 5 integrates the concepts underlying Figures 1, 2, and 4, and information in Tables 1 and 2. The boxes are convenient envelopes for the text, and their relative sizes have no other significance

Reason described the holes in the Swiss cheese as “weaknesses in the defences.” In the integrated model, the holes in the Swiss cheese represent breaching of the cognitive‐affective gates (Figures 2 and 5), permitting cognitive failure; cognitive failure encompasses all varieties of individual, team, and organizational fallibility.71

One or more elements of cognitive‐affective biases plus at organizational, team, and/or individual levels are important contributors to breaches, as are the factors listed in Table 1. Conversely, the factors listed in Table 2 reinforce cognitive‐affective gates. Figure 2 is a simple example of one clinical setting illustrating factors that breach and those that strengthen cognitive‐affective gates; the latter effectively close the holes in the Swiss cheese38 and /or prevent alignment of the holes in successive layers of defence.

Table 2.

Examples of factors promoting correct decisions across the continuum of care

| Organizations, teams, and individuals |

| 1. Constant awareness of the universal susceptibility to cognitive biases plus |

| 2. Promote and practice shared decision making |

| 3. Promote and practice critical thinking |

| 4. Promote and practice critical appraisal of all evidence |

| 5. Promote and practice continuous improvement and learning |

| 6. Be open to seek and encourage rather than discourage the outside view |

| Organizations |

| 1. Create and promote a just culture |

| 2. Encourage and appreciate integrity and dedication to patients and families |

| 3. Encourage staff at all levels to enhance individual and collective mindfulness (acquire error wisdom and resilience) |

| 4. Promote the use of structured checklists custom tailored to the health care situation and organization (eg, in the OR/surgical procedures, ICU, discharge planning, and homecare) |

| 5. Avoid sleep deprivation among staff (as in the airline industry) |

| 6. Ensure adequate staffing and resources; have realistic expectations of the workload that staff can carry without compromising their own health and the health of patients |

| Teams and individuals |

| 1. Practice effective communication, collaboration, and continuous learning |

| 2. Develop mindfulness, error wisdom, and resilience |

| 3. Be proactive about personal health |

| 4. Recognize that humility and compassion are cornerstones of care |

These factors rectify the error‐catalyzing factors listed in Table 1. These factors “gate the holes,” ie, reinforce cognitive‐affective gates in the system. Authors' compilation from several references cited in the text. The list is not meant to be all‐inclusive.

The integrated cognitive‐affective biases plus (cascade)–gated SCM, perhaps abbreviated to the cognitive‐affective–gated SCM, has analogies in cell biology and health care: Virtual gating88; the gate theory of pain89, 90; ion‐gated channels in health and disease91; and sensory, motor, and cognitive gating in Neuropsychiatry.92 Static figures, however complex, and text explanations used in these examples, cannot fully capture the underlying dynamic complexities of the involved structures and processes.

6. DISCUSSION

Like the original SCM, the cognitive‐affective–gated SCM is a systems approach that attempts to explain (1) the spectrum of safety: correct decisions, near misses, minor and major adverse events; and (2) the complex interlinked roles of individuals, teams, organizational factors, and cultures. Thus, the model can be applied to both the “negative” and “positive” aspects of patient safety.18 The latter is the focus of the safety‐II model: The study of how and why things usually go right.36, 87 The potential for adverse consequences is greater if several layers of defence are weakened or breached (the holes aligning in several layers of the Swiss cheese), upstream organizational factors generally being responsible.14

The cognitive‐affective–gated SCM is also a generic tool that can be custom tailored to specific situations across the continuum of care. The model's broad applicability to patient safety is supported by examples of actual or potential individual and/or organizational, often multi‐organizational, cognitive failures such as those associated with (1) antiinfluenza drugs,93, 94 (2) fraudulent or exaggerated published and wasted research,49, 95, 96 (3) opioid misuse,97, 98 (4) problems with drug safety and effectiveness,99, 100 (5) critical incidents in the operating room or during surgery,18, 40, 42 (6) the Bristol Royal Infirmary and Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation tragedies,20, 29, 101, 102 (7) systemic corruption across the spectrum of health care in some countries,103, 104 (8) the apparent manipulation and falsification of wait‐time data at several Veteran Affairs' health care facilities,105 and (9) the causes of the “crisis in EBM.”48 The model may also explain adverse events during phase 1 clinical trials,106 the industrial accidents discussed by Reason,13, 18, 29, 30 and the disparities in health care for social disadvantaged and other groups.69 Unhealthy organizational cultures played a pivotal role in some of the cited examples. The consequences have far‐reaching downstream effects when bad decisions are made or erroneous information disseminated by those who are influential or have authority (Figure 5; breach of Swiss cheese slice A).

Unhealthy organizational cultures are not easily cured29: The mishaps at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust showed nothing had changed since the inquiry into those at the Bristol Royal Infirmary almost a decade earlier.102 The recent “existential crisis” in the NHS lends further support.24

Strength of evidence for the model is enhanced by synthesizing published information authored by different individuals from diverse disciplines such as anthropology, behavioural economics, business management, basic and clinical sciences (including cognitive neuroscience), critical thinking, EBM, ethics, law, patient safety, philosophy, and social sciences.25, 26, 28

Unavoidably, the concepts underlying the model are abstract. Like the SCM and the gate theory of pain, the integrated model is virtual (ie, a physical correlate has not been demonstrated). The supportive evidence is indirect and qualitative; additionally, the data are mainly from developed countries, although limited evidence from other countries suggests that the proposed model can be applied globally.5, 103, 104 Nonetheless, the evidence offered is the current best available, fulfilling a fundamental principle of evidence‐based medicine.107, 108

Our views, like those of others, can be influenced by intellectual CoI and other cognitive‐affective biases plus. Readers are encouraged to critically appraise the secondary and primary references on which our analysis is based,107, 109 and the model will need to be validated by others.

Humans may be fallible but often they do things right.87 In addition, their timely actions have averted mishaps or mitigated the consequences of errors and technical failures; the attributes that facilitate such actions include individual and collective mindfulness.18 More mishaps do not occur in health care, even in organizations with unhealthy cultures, because of the cognitive vigilance, “error wisdom,” and dedication of many in the health care workforce. The value of good organizational cultures and role models cannot be overemphasized.

Health care professionals are generally considered to be the last line of (cognitive‐affective) defence in the health care system.16, 18, 36 However, well‐informed patients and caregivers can serve this role: They are the only constants in the continuum of care and potentially represent the most important defensive layer (Swiss cheese slice C in Figure 5). Shared decision making, the centrepiece of person‐centred health care, is no longer an option but a mandatory element of quality of care.76, 110, 111, 112

7. CONCLUSIONS

Our analysis suggests that the roots of many potential and actual health care errors have intricate cognitive‐affective underpinnings at the levels of the many individuals, teams, and organizations involved in health care. Organizational factors and cultures often play an important role in errors of individuals.14 Reason constantly stressed the link between safety and the “large hidden” cognitive processes that “govern human thought and action”13, 14, 18, 29, 30, 71: The integrated cognitive‐affective–gated SCM is a logical extension of his ideas and our paper a tribute to his contributions and prescience.

The cognitive‐affective–gated SCM may help us appreciate the complexities of cognitive‐affective processes that influence correct and erroneous decisions and actions. The model is based on a systems approach and can be applied to all health care–related disciplines, professionals, and organizations. Thus, the model offers a conceptual framework for the proposed steps to improve patient safety across the spectrum of care globally.1, 8, 10, 11 However, one model may not fully explain all adverse events, and models must be improved continuously as knowledge advances and the landscape of health care changes; often, as one problem is resolved, “others spring up in its place”18, 26, 30, 31: Patient safety is a continuously moving target.113

Complex problems require thoughtful and multifaceted responses.4 Therefore, multipronged system‐based approaches are needed to enhance patient safety across the continuum of care, and the integrated model provides an evidence‐informed framework to evaluate strategies that may result in improvement. Reason's suggestions and those of others, including the roles of mindfulness and cognitive debiasing and strategic reliabilism, for enhancing rational decision making, represent potential protective gating mechanisms: These and other possible solutions11, 14, 15, 18, 25, 26, 28, 30, 48, 49, 54, 61, 68, 87, 109, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120 are worthy of evidence‐informed debate. Informed shared decision making is the critical cornerstone of patient safety. Hence, organizations and health care professionals involved in health care provision and delivery must invest time and effort to make shared decision making a reality. Additionally, the philosophy of shared decision making must become an integral element of health care education. Failure to act will continue to “seriously impede” the “pursuit of greater safety,”15 especially in an era of increasing challenges to health care funding.

NOTE

We have summarized information from 120 references and could only include selections from them. S.S.S. found Reason's 2008 monograph,18 a lucid summary of his earlier writings. The concepts in this paper will be presented by invitation at the fourth annual conference of the European Society for Person Centered Healthcare, October 26 and 27, 2017, London, United Kingdom.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S.S. was responsible for the concepts, coordinating opinions and drafting. P.C. made key contributions to the concepts on patient safety, decision making and critical thinking. Each co‐author made specific contributions to the contents, structure, and revisions, and all approved the final submission. S.S.S. is the guarantor.

This analysis is based on a paediatric grand round (University of Saskatchewan) given by S.S.S. on September 15, 2016.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Drs Bill Albritton, Bill Bingham, Sarah Hillis, Richard Huntsman, Michael Galvin, Neil Guha, Dawn Phillips, Molly Seshia, and Professor Tom Porter for helpful discussion, reviewing drafts and suggesting revisions. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewer for providing the outside view, and suggesting specific refinements. We thank Dr Catherine Boden and Ms Erin Watson of the Leslie and Irene Dubé Health Sciences Library, University of Saskatchewan for helping with literature searches; Dr Boden also advised on the methods section. We thank Ms Phyllis Thomson (former executive director, Epilepsy & Seizure Association Manitoba Inc, Canada) and Ms Debbie Nielsen (parent): Both strong advocates for family‐ and person‐centred care in Manitoba, Canada; they provided a lay, patient, and family perspective on an earlier draft. Errors are our own. S.S.S. acknowledges support from Department of Paediatrics and College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan. Mr Todd Reichert helped refine figures.

Seshia SS, Bryan Young G, Makhinson M, Smith PA, Stobart K, Croskerry P. Gating the holes in the Swiss cheese (part I): Expanding professor Reason's model for patient safety. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:187–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12847

REFERENCES

- 1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine . Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington, DC, USA: The National Academies Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, et al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. Lancet. 2017;390:16‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saini V, Garcia‐Armesto S, Klemperer D, et al. Drivers of poor medical care. Lancet. 2017;390:178‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . To err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jha AK, Prasopa‐Plaizier N, Larizgoitia I, Bates DW. Research priority setting working group of the WHO world alliance for patient safety. Patient safety research: an overview of the global evidence. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(1):42‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Amalberti R, Benhamou D, Auroy Y, Degos L. Adverse events in medicine: easy to count, complicated to understand, and complex to prevent. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(3):390‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carson‐Stevens A, Hibbert P, Williams H, et al. Characterising the nature of nature of primary care patient safety incident reports in the england and wales national reporting and learning system: a mixed‐methods agenda‐setting study for general practice. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2016;4(27). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Panel Expert: The National Patient Safety Foundation . Free from harm: accelerating patient safety improvement fifteen years after to err is human . Boston, MA: 2015. http://www.aig.com/content/dam/aig/america-canada/us/documents/brochure/free-from-harm-final-report.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 9. Gandhi TK, Berwick DM, Shojania KG. Patient safety at the crossroads. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1829‐1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas EJ, Brennan T. Diagnostic adverse events: on to chapter 2: comment on “patient record review of the incidence, consequences, and causes of diagnostic adverse events”. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1021‐1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Croskerry P. Perspectives on diagnostic failure and patient safety. Healthc Q. 2012;15 Spec No:50‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Croskerry P. To err is human—and let's not forget it. CMAJ. 2010;182(5):524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reason J. Human Error. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp.1‐2;p.208. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reason J. Understanding adverse events: human factors. Qual Health Care. 1995;4(2):80‐89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reason J. Human error: models and management. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):768‐770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reason J. Beyond the organisational accident: the need for “error wisdom” on the frontline. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 2):ii28‐33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reason J. Safety in the operating theatre—part 2: human error and organisational failure. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):56‐60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reason J. The Human Contribution:Unsafe Acts, Accidents and Heroic Recoveries. Surrey, England, UK: Ashgate; 2008. pp.7, 37‐38, 71, 93‐103, 184‐194,239‐263. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chokshi DA, Chang JE, Wilson RM. Health reform and the changing safety net in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1790‐1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cox J, Gray A. Medicine of the person: a charter for change following the Mid‐Staffordshire Francis enquiry. European Journal for Person‐Centered Healthcare. 2013;2:217‐219. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frith L. The changing face of the English National Health Service: new providers, markets and morality. Br Med Bull. 2016;119(1):5‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Berwick DM. The toxic politics of health care. JAMA. 2013;310(18):1921‐1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schneider EC, Squires D. From last to first—could the U.S. health care system become the best in the world? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(10):901‐904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ford S, Lintern S. Sir Robert Francis warns current NHS pressures make another mid staffs ‘inevitable’. The Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/policies-and-guidance/current-nhs-pressures-make-another-mid-staffs-inevitable/7015558.article. Accessed September 27. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Seshia SS, Makhinson M, Young GB. Evidence‐informed person‐centred health care (part II): are 'cognitive biases plus' underlying the EBM paradigm responsible for undermining the quality of evidence? J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(6):748‐758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seshia SS, Makhinson M, Young GB. ‘Cognitive biases plus’: covert subverters of healthcare evidence. Evid Based Med. 2016;21(2):41‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26(2):91‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Seshia SS, Makhinson M, Phillips DF, Young GB. Evidence‐informed person‐centered healthcare part I: do ‘cognitive biases plus’ at organizational levels influence quality of evidence? J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(6):734‐747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reason J. A Life in Error. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 2013. pp.xi, 74‐76, 82‐83, 121, 123‐124. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reason J. Managing the Risks of Organizational Accidents. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited; 1997:9‐13. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reason J, Hollnagel E, Paries J. Revisiting the Swiss cheese model of accidents. 2006;EEC Note No.13/06. https://www.eurocontrol.int/eec/gallery/content/public/document/eec/report/2006/017_Swiss_Cheese_Model.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 32. Reason J. James reason: patient safety, human error, and Swiss cheese. Interview by Karolina Peltomaa and Duncan Neuhauser. Qual Manag Health Care. 2012;21(1):59‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kapur N, Parand A, Soukup T, Reader T, Sevdalis N. Aviation and healthcare: a comparative review with implications for patient safety. JRSM Open. 2015;7(1): 2054270415616548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McNutt R, Hasler S. The hospital is not your home: making safety safer (Swiss cheese is a culinary missed metaphor). Qual Manag Health Care. 2011;20(3):176‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perneger TV. The Swiss cheese model of safety incidents: are there holes in the metaphor? BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carthey J. Understanding safety in healthcare: the system evolution, erosion and enhancement model. J Public Health Res. 2013;2(3): e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Y, Thimbleby H. Hot cheese: a processed Swiss cheese model. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2014;44(2):116‐121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stein JE, Heiss K. The Swiss cheese model of adverse event occurrence—closing the holes. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2015;24(6):278‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raheja D, Escano MC. Swiss cheese model for investigating the causes of adverse events . J System Safety. 2011;47 (6) eEdition. http://www.system-safety.org/ejss/past/novdec2011ejss/pdf/healthcare.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Beuzekom M, Boer F, Akerboom S, Hudson P. Patient safety: latent risk factors. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105(1):52‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Beuzekom M, Boer F, Akerboom S, Hudson P. Patient safety in the operating room: an intervention study on latent risk factors. BMC Surg. 2012;12: 10‐2482‐12‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carthey J, de Leval MR, Reason JT. The human factor in cardiac surgery: errors and near misses in a high technology medical domain. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(1):300‐305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Veltman LL. Getting to Havarti: moving toward patient safety in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1146‐1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Collins SJ, Newhouse R, Porter J, Talsma A. Effectiveness of the surgical safety checklist in correcting errors: a literature review applying Reason's Swiss cheese model. AORN J. 2014;100(1):65‐79. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Field RI. Why is health care regulation so complex? P T. 2008;33(10):607‐608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sutherland J, Hellsten E. Integrated funding: connecting the silos for the healthcare we need. Commentary no. 463. C.D.Howe institute. https://www.cdhowe.org/research-main-categories/health-policy. 2017. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 47. Frandsen BR, Joynt KE, Rebitzer JB, Jha AK. Care fragmentation, quality, and costs among chronically ill patients. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(5):355‐362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N. Evidence based medicine renaissance group. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348: g3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ioannidis JP. How to make more published research true. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10): e1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ioannidis JPA. Hijacked evidence‐based medicine: stay the course and throw the pirates overboard. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;84:11‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organizational_culture. Last edited August 31, 2017. Accessed September 10, 2017.

- 52. Westrum R. A typology of organisational cultures. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13: Suppl 2:ii22‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Parker D, Lawrie M, Hudson P. A framework for understanding the development of organisational safety culture. Safety Science. 2006;44:551‐562. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Croskerry P. From mindless to mindful practice—cognitive bias and clinical decision making. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(26):2445‐2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Popa LS, Hewitt AL, Ebner TJ. The cerebellum for jocks and nerds alike. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Salman MS, Tsai P. The role of the pediatric cerebellum in motor functions, cognition, and behavior: a clinical perspective. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2016;26(3):317‐329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van den Heuvel MP, Sporns O. Network hubs in the human brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(12):683‐696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stanovich KE, West RF. Individual differences in reasoning: implications for the rationality debate? Behav Brain Sci. 2000;23(5):645‐665. discussion 665‐726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kahneman D. (Ed). Thinking, Fast and Slow. Canada: Doubleday Canada; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Norman G, Monteiro S, Sherbino J. Is clinical cognition binary or continuous? Acad Med. 2013;88(8):1058‐1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med. 2017;92(1):23‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Burgess DJ. Are providers more likely to contribute to healthcare disparities under high levels of cognitive load? How features of the healthcare setting may lead to biases in medical decision making. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(2):246‐257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Croskerry P. Shiftwork, fatigue and safety in emergency medicine In: Croskerry P, Cosby K, Schenkel S, Wears R, eds. Patient Safety in Emergency Medicine. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008:259‐268. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Croskerry P. ED cognition: any decision by anyone at any time. CJEM. 2014;16(1):13‐19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Heyhoe J, Birks Y, Harrison R, O'Hara JK, Cracknell A, Lawton R. The role of emotion in patient safety: are we brave enough to scratch beneath the surface? J R Soc Med. 2016;109(2):52‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hockey G, Maule A, Clough P, Bdzola L. Effects of negative mood states on risk in everyday decision making. Cognit Emot. 2000;14:823‐855. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hogarth R. Educating Intuition. Chicago, USA: The University of Chicago Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Croskerry P, Abbass A, Wu AW. Emotional influences in patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2010;6(4):199‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fiscella K, Sanders MR. Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:375‐394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):248‐255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Reason J. Stress and cognitive failure In: Fisher S, Reason J, eds. Handbook of Life Stress Cognition and Health. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1988:405‐420. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zwaan L, Monteiro S, Sherbino J, Ilgen J, Howey B, Norman G. Is bias in the eye of the beholder? A vignette study to assess recognition of cognitive biases in clinical case workups. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;26:104‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Norman G. The bias in researching cognitive bias. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2014;19(3):291‐295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Croskerry P. Diagnostic failure: A cognitive and affective approach In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, eds. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2005. NBK20487 [bookaccession]. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pronin E. Perception and misperception of bias in human judgment. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11(1):37‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mold JW, Stein HF. The cascade effect in the clinical care of patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(8):512‐514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Viswanathan M, Carey TS, Belinson SE, et al. A proposed approach may help systematic reviews retain needed expertise while minimizing bias from nonfinancial conflicts of interest. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(11):1229‐1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Bero LA, Grundy Q. Why having a (nonfinancial) interest is not a conflict of interest. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(12): e2001221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Akl EA, El‐Hachem P, Abou‐Haidar H, Neumann I, Schunemann HJ, Guyatt GH. Considering intellectual, in addition to financial, conflicts of interest proved important in a clinical practice guideline: a descriptive study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(11):1222‐1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Marshall E. When does intellectual passion become conflict of interest? Science. 1992;257(5070):620‐623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Stead WW. The complex and multifaceted aspects of conflicts of interest. JAMA ‐ Journal of the American Medical Association. 2017;317:1765‐1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bell R, Schain C, Echterhoff G. How selfish is memory for cheaters? Evidence for moral and egoistic biases. Cognition. 2014;132(3):437‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bion J. Financial and intellectual conflicts of interest: confusion and clarity. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(6):583‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cain DM, Detsky AS. Everyone's a little bit biased (even physicians). JAMA. 2008;299(24):2893‐2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Mazar N, Ariely D. Dishonesty in scientific research. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(11):3993‐3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shu LL, Gino F. Sweeping dishonesty under the rug: how unethical actions lead to forgetting of moral rules. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2012;102(6):1164‐1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hollnagel E, Wears RL, Braithwaite J. From safety‐I to safety‐II: A White paper. The resilient health care net: published simultaneously by the University of Southern Denmark, University of Florida, USA, and Macquarie University, Australia. 2015. http://resilienthealthcare.net/onewebmedia/WhitePaperFinal.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 88. Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Magnasco MO, Chait BT. Virtual gating and nuclear transport: the hole picture. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(12):622‐628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150(3699):971‐979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Melzack R. From the gate to the neuromatrix. Pain. 1999; Suppl 6:S121‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ashcroft FM. From molecule to malady. Nature. 2006;440(7083):440‐447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Swerdlow NR, Braff DL, Geyer MA. Sensorimotor gating of the startle reflex: what we said 25 years ago, what has happened since then, and what comes next. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(11):1072‐1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Jefferson T, Doshi P. Multisystem failure: the story of anti‐influenza drugs. BMJ. 2014;348:g2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Jefferson T. The neuraminidase inhibitors evidence of harms—in context. Infect Dis (Lond). 2016;48(9):661‐662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Wiedermann CJ. Ethical publishing in intensive care medicine: a narrative review. World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5(3):171‐179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Smith R, Godlee F. A major failure of scientific governance. BMJ. 2015;351:h5694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Gomes T, Juurlink DN. Opioid use and overdose: what we've learned in Ontario. Healthc Q. 2016;18(4):8‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Lin DH, Lucas E, Murimi IB, Kolodny A, Alexander GC. Financial conflicts of interest and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's 2016 guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(3):427‐428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Light DW, Lexchin J, Darrow JJ. Institutional corruption of pharmaceuticals and the myth of safe and effective drugs. J Law Med Ethics. 2013;41(3):590‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Light DW, Lexchin J. The FDA's new clothes. BMJ. 2015;351:h4897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Smith R. All changed, changed utterly. British medicine will be transformed by the Bristol case. BMJ. 1998;316(7149):1917‐1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Newdick C, Danbury C. Culture, compassion and clinical neglect: probity in the NHS after Mid Staffordshire. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(12):956‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Chattopadhyay S. Corruption in healthcare and medicine: why should physicians and bioethicists care and what should they do? Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10(3):153‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Blasszauer B. Bioethics and corruption: a personal struggle. Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10(3):171‐175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Kizer KW, Jha AK. Restoring trust in VA health care. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):295‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Bonini S, Rasi G. First‐in‐human clinical trials—what we can learn from tragic failures. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1788‐1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Guyatt G, Rennie D, Meade MO, Cook DJ, eds. Users' Guides to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence‐based Clinical Practice. 3rd ed. New York: The JAMA Network & McGraw Hill Education; 2015. pp.xxiv, 39. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312(7023):71‐72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Jenicek M, Hitchcock DL. (Eds). Evidence‐based Practice: Logic and Critical Thinking in Medicine. USA: AMA Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Barry MJ, Edgman‐Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient‐centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780‐781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Berry LL, Danaher TS, Beckham D, Awdish RLA, Mate KS. When patients and their families feel like hostages to health care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1373‐1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Montori VM, Kunneman M, Hargraves I, Brito JP. Shared decision making and the internist. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;37:1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Vincent C, Amalberti R. Safety in healthcare is a moving target. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(9):539‐540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. McKee M, Stuckler D. Reflective practice: how the World Bank explored its own biases? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;5(2):1‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Bishop M, Trout J. Epistemology and the Psychology of Human Judgment. New York, USA: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 116. Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 Suppl):S2‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Croskerry P, Singhal G, Mamede S. Cognitive debiasing 2: impediments to and strategies for change. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(Suppl 2):ii65‐ii72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Lambe KA, O'Reilly G, Kelly BD, Curristan S. Dual‐process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic reasoning: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(10):808‐820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Croskerry P, Norman G. Overconfidence in clinical decision making. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 Suppl):S24‐S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Jenicek M, Croskerry P, Hitchcock DL. Evidence and its uses in health care and research: the role of critical thinking. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17(1):RA12‐RA17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]