Abstract

Objective To integrate data elements from multiple sources for informing comprehensive and standardized collection of family health history (FHH).

Materials and methods Three types of sources were analyzed to identify data elements associated with the collection of FHH. First, clinical notes from multiple resources were annotated for FHH information. Second, questions and responses for family members in patient-facing FHH tools were examined. Lastly, elements defined in FHH-related specifications were extracted for several standards development and related organizations. Data elements identified from the notes, tools, and specifications were subsequently combined and compared.

Results In total, 891 notes from three resources, eight tools, and seven specifications associated with four organizations were analyzed. The resulting Integrated FHH Model consisted of 44 data elements for describing source of information, family members, observations, and general statements about family history. Of these elements, 16 were common to all three source types, 17 were common to two, and 11 were unique. Intra-source comparisons also revealed common and unique elements across the different notes, tools, and specifications.

Discussion Through examination of multiple sources, a representative and complementary set of FHH data elements was identified. Further work is needed to create formal representations of the Integrated FHH Model, standardize values associated with each element, and inform context-specific implementations.

Conclusions There has been increased emphasis on the importance of FHH for supporting personalized medicine, biomedical research, and population health. Multi-source development of an integrated model could contribute to improving the standardized collection and use of FHH information in disparate systems.

Keywords: family health; medical history taking; electronic health records; genomics; narration; models, theoretical

Background and significance

Since the advent of the genomic era,1 there has been renewed interest and emphasis on the importance of family health history (FHH) for individualized disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.2–13 FHH has been described as a simple yet invaluable tool for risk assessment and is incorporated in a number of recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (eg, screening for BRCA-related cancer risk in women,14 lipid disorders in adults,15,16 and osteoporosis17).5,18,19 While the role of FHH is clearly recognized for personalized medicine and population health, numerous barriers to its optimal collection and use have been described including: limited time and resources; insufficient knowledge for interpretation by providers; uncertainty of family composition and health history by patients; and lack of standards for data elements, terminology, structure, interoperability, presentation, and clinical decision support rules.18,20–24 In response to these challenges, multiple initiatives have emerged that emphasize the importance of FHH and the need for more effective use (eg, U.S. Surgeon General's Family History Initiative,25 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Public Health Genomics (CDC/OPHG) Family History Public Health Initiative,26 National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference on Family History and Improving Health,27 and Talk Health History Campaign supported by The American Society of Human Genetics and Genetic Alliance28).

Increasing efforts over the last decade have focused on the development and use of computer-based tools for facilitating the collection, maintenance, and analysis of detailed FHH.23,29–36 The electronic health record (EHR) provides an important mechanism for documentation by providers where related efforts include a core Stage 2 Meaningful Use measure for structured data entry of FHH37 and several natural language processing (NLP) tools for extracting FHH information from clinical notes.38–42 Consumer-oriented resources include personal health record systems and patient-facing FHH tools where these tools range from those that have been developed and evaluated as part of federal initiatives (eg, U.S. Surgeon General's My Family Health Portrait43–45 and CDC's Family Healthware46,47) to those from university-affiliated research efforts (eg, MeTree,48–52 Health Heritage,53 and OurFamilyHealth54). The development and use of standards to support interoperability across systems continues to be emphasized55 and FHH-related specifications include the HL7 Clinical Genomics FHH (Pedigree) Model56–58 and a minimum core data set defined by the American Health Information Community (AHIC; now known as the National eHealth Collaborative (NeHC)) FHH Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup.59

In our previous work, the adequacy of existing standards (HL7 Clinical Genomics FHH Model and HL7 Clinical Statement Model) was evaluated for representing FHH information in clinical notes from University of Minnesota-affiliated Fairview Health Services.60 These notes were analyzed to identify different types of FHH statements and elements of information within these statements such as disease, family member, living status, negation, and uncertainty. Data elements identified in the notes were combined with those in the two HL7 models to create a ‘Merged Family History Model’ (henceforth referred to as the ‘Integrated FHH Model’). A subsequent study involving analysis of free-text comments within the primarily structured family history module of the EHR system at Fletcher Allen Health Care (FAHC), the academic health center affiliated with the University of Vermont, served to validate the Integrated FHH Model.61 Findings from these early studies highlighted the need for further refinements to accommodate the full breadth of FHH information documented in the EHR and other key sources.

Objective

Building upon the aforementioned efforts, the objective of this study was to enhance the Integrated FHH Model for informing the standardized collection and use of FHH in disparate systems. Multiple sources were explored to identify a comprehensive set of data elements and characterize the complementary nature of these sources as well as potential gaps in individual resources.

Materials and methods

The general approach involved analysis of three types of sources to identify data elements associated with the collection of FHH: (1) clinical notes, (2) patient-facing FHH tools, and (3) FHH-related specifications. Data elements identified from these notes, tools, and specifications were subsequently combined and compared.

Analysis of clinical notes

Clinical notes from three resources were collected and analyzed for FHH information: (1) MTSamples.com, (2) the Open Clinical Report Repository, and (3) FAHC. MTSamples.com (MTS) is a public web repository of almost 5000 sample transcription reports, including 491 notes categorized as ‘Consult—History and Physical’ (as of October 2012) that were used in this study.62 The Open Clinical Report Repository was developed as a community resource to support NLP research and development.63 This repository contains nine types of reports from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), including history and physical notes from which a sample of 200 notes was obtained. Finally, 200 transcribed notes categorized as consult or evaluation notes were obtained from the legacy clinical information system at FAHC.64 Collectively, these three sets included note types that typically include family history sections and covered both the inpatient and outpatient settings as well as a range of specialties (eg, cardiology, general medicine, oncology, and pediatrics).

Two open-source tools were used for manual annotation of FHH sections, sentences, and statements in each set of notes where a statement is defined as individual discrete items of information within a sentence. For example, the sentence ‘mother and sister had breast cancer’ includes two statements: (1) ‘mother had breast cancer’ and (2) ‘sister had breast cancer.’ Annotation of sections and sentences involved use of the General Architecture for Text Engineering (GATE).65 A GATE annotation schema and guidelines were developed for defining two types of annotations: (1) FHH sections—section headers associated with FHH sentences (eg, ‘Family History,’ ‘FHX,’ or ‘History of Present Illness’) and (2) FHH sentences—consecutive sentences including FHH information.

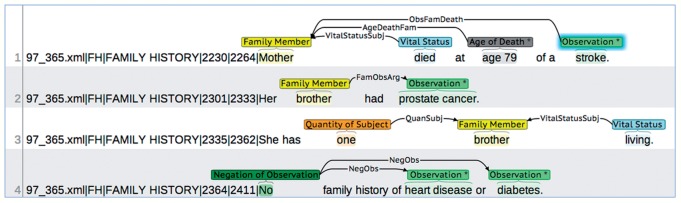

For each annotated sentence (extracted from the GATE Extensible Markup Language (XML) output), the brat rapid annotation tool (BRAT) was then used to annotate FHH statements based on an annotation schema defining the set of entities, entity attributes, and relationships between entities.66,67 The initial version of this schema was based on the first version of the Integrated FHH Model described earlier. For example, the entity Observation can be used to annotate a word or phrase describing a particular clinical observation (eg, ‘diabetes,’ ‘breast cancer,’ or ‘CABG’), has an attribute for specifying the Observation Type (ie, ‘Disease,’ ‘Procedure,’ ‘Medication,’ ‘Lab Test,’ or ‘Other’), and can be linked to other entities such as Family Member (eg, ‘mother’⇒‘diabetes’) or Onset Date (eg, ‘1980’⇒‘breast cancer’). Annotation guidelines were also developed that included descriptions and examples for each entity, attribute, and relationship (see online supplementary appendix A). Figure 1 depicts the annotation of FHH information in a set of sentences using the defined annotation schema and guidelines.

Figure 1:

Annotation of family health history (FHH) statements in clinical notes. Each line represents a sentence where the first five fields (separated by ‘|’) represent information extracted from the GATE XML output (filename, annotation type, section header, and start and end positions). FHH information is annotated in each sentence (‘*’ indicates an attribute value and shadowing indicates a free-text note). Arrows represent relationships between entities where directionality matters (eg, ‘ObsFamDeath’ indicates that the Observation is the cause of death for the Family Member).

An iterative process was used for annotating each set of notes using GATE and BRAT. A subset of 100 MTS notes was initially annotated and annotations were revised based on multiple review sessions to achieve consensus between four annotators before separately proceeding with the remaining 391 notes. Throughout this process, the BRAT annotation schema and guidelines underwent several revisions to accommodate for additional entities and relationships. For example, the entity Quantity of Observation and relationship to Observation were added after encountering a statement referring to ‘multiple strokes.’ For the UPMC and FAHC sets, a subset of 10 (5%) notes was first annotated and reviewed by two annotators to achieve consensus before proceeding with the remaining notes.

Analysis of patient-facing FHH tools

A series of literature and web searches was performed to identify patient-facing FHH tools. Preliminary searches focused on publications including lists of tools12,21,32 and web resources such as the American Medical Association (AMA) Family Medical History,68 CDC/OPHG FHH,69 and Talk Health History Campaign.28 A list of 24 tools was generated from these searches, including those focused on pediatric patients as well as specific diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. The following criteria were then used to select an initial subset for further analysis: general audience or adult-oriented, general health or cancer-specific, and available as an interactive web-based tool or in a web-accessible paper-based format (eg, PDF form). The resulting subset of eight tools included: (1) Adult Family History Form (AMA),68 (2) Cancer Family Tree (University of Nebraska Medical Center),70 (3) Colon Cancer Risk Assessment (Cleveland Clinic),71 (4) Does It Run in the Family? Toolkit (Genetic Alliance),72 (5) FHH Toolkit (Utah Department of Health),73 (6) Family HealthLink (The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center),74 (7) Family Healthware (CDC (version obtained under a Material Transfer Agreement for this study; not the publicly-accessible web tool)),46,75 and (8) My Family Health Portrait (U.S. Surgeon General).43

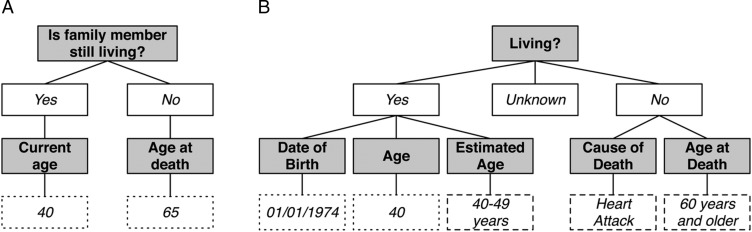

For each tool, two reviewers analyzed questions and responses related to family structure or individual family members; questions related to the patient were excluded (eg, patient demographics and health history). For example, the question ‘Is family member still living?’ from the Cancer Family Tree tool and ‘Living?’ from My Family Health Portrait both correspond to living status. Depending on the response, additional questions are asked where responses are either selected from a pre-defined list of values or provided as free text (figure 2).

Figure 2:

Questions and responses for living status from patient-facing family health history (FHH) tools. From the University of Nebraska Medical Center's Cancer Family Tree (A) and the U.S. Surgeon General's My Family Health Portrait (B). Gray shaded boxes indicate questions and white boxes indicate responses (solid border indicates all possible responses; dashed line indicates example response selected from a list of available values; dotted line indicates example free-text response).

Analysis of FHH-related specifications

In addition to revisiting HL7 International, three additional standards development and related organizations representing both national and international efforts were explored for FHH-related specifications (subsequently analyzed by two reviewers): Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP), AHIC, and openEHR. For HL7, the latest HL7 V.3 Implementation Guide: Family History/Pedigree Interoperability, Release 1 was reviewed for elements defined in its Family History Model and related vocabulary (eg, HL7 V.3 Vocabulary for RoleCode that includes a list of family members).58,76 These elements were supplemented with those from the HL7 Implementation Guide for CDA Release 2: IHE Health Story Consolidation, Release 1.1, specifically for Family History Section, Family History Organizer, Family History Observation, Family History Death Observation, and Age Observation.77

Within the HITSP/C154 Data Dictionary Component, V.1.0.1 that defines the library of data elements for standards-based exchange, only those listed in the Family History Module were included.78 From the FHH Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup Dataset Requirements Summary presented to the Personalized Health Care Workgroup of AHIC, data items associated with each core dataset requirement were considered elements and included with the exception of those associated with basic desired functionality (eg, ‘Free text shall be minimized for data entry of family history’ or ‘Capture data that allows for generation of a pedigree’).79 Finally, the openEHR Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM) was used to search for any archetype related to family history where three relevant archetypes were identified: Exclusion of Family History, Family History, and Risk of condition based on family history.80 Each of these archetypes was analyzed to create a combined list of elements for openEHR.

Integration and comparison of FHH data elements

The analysis of three sets of notes, eight tools, and specifications associated with four organizations resulted in 15 separate lists of FHH-related information that were used to define a set of data elements for the second version of the Integrated FHH Model. A consensus-based process was used to standardize each ‘source list,’ which involved creating a ‘master list’ of elements with preferred names and mapping information in each of the source lists to the corresponding preferred element names. For example, ‘Vital Status’ in the BRAT annotation schema for clinical notes (figure 1), the questions ‘Is family member still living?’ and ‘Living?’ from two patient-facing FHH tools (figure 2), ‘deceasedInd’ from the HL7 models, and ‘Deceased?’ from one of the openEHR archetypes were mapped to the preferred element name Living Status. Once standardized, inter- and intra-source comparisons were conducted to characterize the contributions of each source type (notes, tools, and specifications) as well as sources within each type.

Results

In total, 891 clinical notes (1071 sentences and 1658 statements) from three resources, eight patient-facing FHH tools, and seven FHH-related specifications associated with four organizations were examined. Table 1A presents the number of FHH sentences and statements annotated in each set of notes, table 1B provides brief descriptions and the estimated number of questions (general and specific to individual family members) for each tool, and table 1C includes the estimated number of elements or requirements defined in each specification. See online supplementary appendices A, B, and C for the full mappings of elements for notes, tools, and specifications, respectively.

Table 1:

Summary of sources

| (A) Notes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Note type(s) | No. of notes | No. of notes with FHH | No. of FHH sentences | No. of FHH statements |

| MTSamples.com (MTS) | Consult–H&P | 491 | 270 (55%) | 541 | 850 |

| UPMC | H&P | 200 | 136 (68%) | 198 | 273 |

| FAHC | Consult; evaluation | 200 | 130 (65%) | 332 | 535 |

| Total | 891 | 536 (60%) | 1071 | 1658 | |

| (B) Tools | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Affiliation | Target conditions | Target audience | Format | Availability | No. of questions* |

| Adult Family History Form | American Medical Association | General | Adult | PDF form | Public | 6–8 |

| Cancer Family Tree | University of Nebraska Medical Center | Cancer | General | Web tool | Public | 8 (2) |

| Colon Cancer Risk Assessment | Cleveland Clinic | Colon Cancer | General | Web tool | Public | 4–8 |

| Does It Run in the Family? Toolkit† | Genetic Alliance | General | General | PDF guide/form |

Public | 8 (1) 12 (1) 7 (2) |

| FHH Toolkit‡ | Utah Department of Health | General | General | PDF guide/form |

Public | 10 12 |

| Family HealthLink | The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center | Cancer and heart disease | General | Web tool | Public | 7–8 (3) |

| Family Healthware | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Six including cancer | General | Web tool | MTA§ | 6 (12) |

| My Family Health Portrait | U.S. Surgeon General | General | General | Web tool | Public | 15 (12) |

| (C) Specifications | |

|---|---|

| Source | No. of elements/requirements¶ |

| HL7 V.3 Implementation Guide: Family History/Pedigree Interoperability, Release 1—US Realm (April 2013) | 25 |

| HL7 Implementation Guide for CDA Release 2: IHE Health Story Consolidation, DSTU Release 1.1 (US Realm) Draft Standard for Trial Use (July 2012) | 11 |

| HITSP/C154 HITSP Data Dictionary Component V.1.0.1 (January 31, 2010) | 26 |

| AHIC PHC Workgroup FHH Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup Dataset Requirements Summary (March 2008) | 44 |

| openEHR Archetype ‘Exclusion of Family History‘ (March 2, 2010) | 3 |

| openEHR Archetype ‘Family History’ (December 15, 2010) | 16 |

| openEHR Archetype ‘Risk of condition based on family history’ (March 2, 2010) | 18 |

*Number or range of questions/instructions specific to individual family members (number of general questions/instructions related to defining family structure (eg, quantity and relationships)).

†Three components included: (1) A Guide to FHH, (2) FHH Questionnaire, and (3) Healthcare Provider Card.

‡Two components included: (1) 10 Questions to Ask Your Family and (2) Health Family Tree Tool.

§Accessed through a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) for the purposes of this study.

¶Estimated number of elements/requirements based on family history-related components of each specification.

AHIC, American Health Information Community; EHR, electronic health record; FAHC, Fletcher Allen Health Care; FHH, family health history; H&P, history and physical; HITSP, Health Information Technology Standards Panel; PHC, personalized health care; UPMC, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

Integration and inter-source comparison of data elements

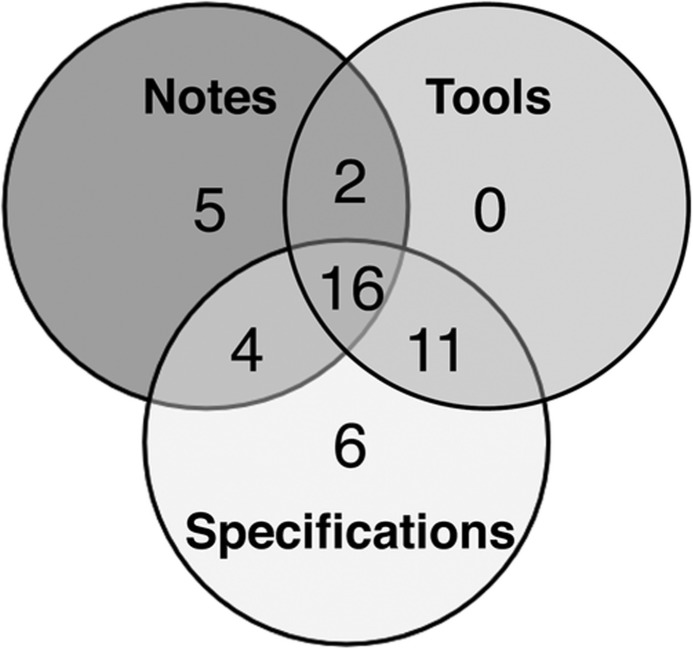

The resulting Integrated FHH Model consisted of 44 data elements organized into four sections: (1) Source—one element for source of information; (2) General—two elements for representing general statements about FHH; (3) Family Member—29 elements for describing family members such as relation type, demographics, and living status; and (4) Observation—12 elements for describing specific family member observations such as diseases, procedures, genetic tests, social and behavioral factors, or general health status.

Table 2 depicts the distribution of elements across the three types of sources and also highlights the addition of 28 elements in the second version of the model (V2) compared with the first version (V1). Figure 3 further highlights the contribution of each source type in terms of common and unique elements. Of the 44 elements, 16 (36%) were common to all three source types (eg, Current Age, Age at Death, and Age at Onset), 17 (39%) were common to two source types (eg, Multiple Birth Status, Ancestry, and Date of Onset), and 11 (25%) were unique to one source type (eg, Quality of Relationship, Multiple Birth Order, and Strength of Observation).

Table 2:

Data elements in the Integrated FHH Model

| Element | Model–V1 (16) | Notes (27) | Tools (29) | Specifications (37) | Model–V2 (44) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | |||||

| Source of information | • | • | • | ||

| General | |||||

| General statement | • | • | |||

| General statement type | • | • | |||

| Family member | |||||

| Side of family | • | • | • | • | • |

| Family member | • | • | • | • | • |

| Genetic relationship | • | • | • | ||

| Half relationship | • | • | • | • | |

| Step relationship | • | • | • | • | |

| Degree of relationship | • | • | • | ||

| Quality of relationship | • | • | |||

| Adoptive status | • | • | • | ||

| Foster status | • | • | • | ||

| Multiple birth status | • | • | • | • | |

| Multiple birth order | • | • | |||

| Consanguinity | • | • | |||

| Name | • | • | • | ||

| Sex | • | • | • | ||

| Gender | • | • | • | • | |

| Place of birth | • | • | • | ||

| Date of birth | • | • | • | • | |

| Current age | • | • | • | • | • |

| Race | • | • | • | • | |

| Ethnicity | • | • | • | • | |

| Ancestry | • | • | • | ||

| Partner status | • | • | |||

| Living status | • | • | • | • | • |

| Date of death | • | • | • | • | • |

| Age at death | • | • | • | • | • |

| Cause of death | • | • | • | • | |

| Certainty of family member | • | • | • | ||

| Negation of family member | • | • | |||

| Quantity of family member | • | • | • | ||

| Observation | |||||

| Observation | • | • | • | • | • |

| Observation type | • | • | • | • | |

| Date of onset | • | • | • | • | |

| Age at onset | • | • | • | • | • |

| Certainty of observation | • | • | • | • | • |

| Negation of observation | • | • | • | • | • |

| Quantity of observation | • | • | • | • | |

| Relevance of observation | • | • | |||

| Severity of observation | • | • | |||

| Strength of observation | • | • | |||

| Status of observation | • | • | |||

| Temporality of observation | • | • | • | • |

(n) indicates total number of elements.

FHH, family health history.

Figure 3:

Common and unique family health history (FHH) elements across source types.

Intra-source comparison of data elements: notes

The clinical notes from MTS, UPMC, and FAHC contributed 25, 17, and 26 elements to the Integrated FHH Model, respectively (table 3). The elements Half Relationship, Step Relationship, and Degree of Relationship were included due to values annotated for Family Member such as ‘half sister,’ ‘stepdaughter,’ and ‘first-degree relative’ (denoted with ‘*’ in table 3). Similarly, based on analysis of the General Statement annotations, initial categories for General Statement Type were identified such as: Nonsignificant/Noncontributory (eg, ‘family history noncontributory’ or ‘there is no significant family history’), Unchanged (eg, ‘reviewed and unchanged’), Unknown/Unavailable (eg, ‘not available at this current time’ or ‘unobtainable’), Negative (eg, ‘negative history’ or ‘none’), and Positive (eg, ‘family history is positive’).

Table 3:

Comparison of FHH elements across notes

| MTS (n = 850 statements) (n = 25 elements) |

UPMC (n = 273 statements) (n = 17 elements) |

FAHC (n = 535 statements) (n = 26 elements) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | No. | Percent | Unique values | No. | Percent | Unique values | No. | Percent | Unique values |

| Source | |||||||||

| Source of information | 3 | 0.4 | 3 | – | – | – | 2 | 0.4 | 2 |

| General | |||||||||

| General statement | 93 | 10.9 | 38 | 45 | 16.5 | 21 | 45 | 8.4 | 28 |

| General statement type | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Family member | |||||||||

| Side of family | 73 | 8.6 | 14 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 57 | 10.7 | 12 |

| Family member | 510 | 60.0 | 71 | 120 | 44.0 | 23 | 407 | 76.1 | 54 |

| Half relationship | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Step relationship | * | * | * | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Degree of relationship | * | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * |

| Current age | 30 | 3.5 | 22 | – | – | – | 72 | 13.5 | 43 |

| Ancestry | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | 0.9 | 5 |

| Living status | 161 | 18.9 | 9 | 45 | 16.5 | 5 | 80 | 15.0 | 5 |

| Date of death | 3 | 0.4 | 3 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 4 | 0.8 | 3 |

| Age at death | 92 | 10.8 | 57 | 20 | 7.3 | 11 | 34 | 6.4 | 25 |

| Cause of death† | 115 | 13.5 | 1 | 31 | 11.4 | 1 | 52 | 9.7 | 1 |

| Certainty of family member | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | – | – | – | 4 | 0.8 | 3 |

| Negation of family member | 9 | 1.1 | 2 | – | – | – | 3 | 0.6 | 2 |

| Quantity of family member | 82 | 9.7 | 21 | 19 | 7.0 | 7 | 70 | 13.1 | 15 |

| Observation | |||||||||

| Observation | 720 | 84.7 | 289 | 216 | 79.1 | 107 | 460 | 86.0 | 249 |

| Observation type | 720 | 84.7 | 4 | 216 | 79.1 | 3 | 460 | 86.0 | 5 |

| Date of onset | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8 | 1.5 | 7 |

| Age at onset | 24 | 2.8 | 19 | 8 | 2.9 | 7 | 22 | 4.1 | 17 |

| Certainty of observation | 80 | 9.4 | 21 | 54 | 19.8 | 7 | 20 | 3.7 | 11 |

| Negation of observation | 98 | 11.5 | 7 | 41 | 15.0 | 5 | 63 | 11.8 | 6 |

| Quantity of observation | 9 | 1.1 | 6 | – | – | – | 4 | 0.8 | 4 |

| Relevance of observation | 9 | 1.1 | 4 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 5 | 0.9 | 3 |

| Strength of observation | 88 | 10.4 | 6 | 25 | 9.2 | 5 | 32 | 6.0 | 7 |

| Temporality of observation | 16 | 1.9 | 11 | – | – | – | 10 | 1.9 | 9 |

Values are number and percentage of statements.

*Included due to values for General Statement or Family Member.

†Determined from relationship between Family Member and Observation.

FAHC, Fletcher Allen Health Care; FHH, family health history; UPMC, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

The most frequent elements across the three sets were Observation, Observation Type, Family Member, and Living Status. Other more frequent elements included Cause of Death and Negation of Observation (eg, ‘no family history of heart disease’ or ‘negative for heart disease’) for MTS; Certainty of Observation (eg, ‘probably healthy’ or ‘questionable history of coronary artery disease’) and General Statement for UPMC; and Current Age and Quantity of Family Member (eg, ‘multiple brothers and sisters’ or ‘three half-sisters’) for FAHC. Ancestry (eg, ‘mother is of English descent’) and Date of Onset were unique to FAHC where the former was primarily found in genetic consultation notes.

Intra-source comparison of data elements: tools

Collectively, the eight patient-facing FHH tools provided a total of 29 data elements where the range was a minimum of nine elements and a maximum of 22 elements (table 4). Similar to the notes, several elements such as Side of Family and Observation Type were included due to values for Family Member (eg, ‘maternal grandmother’) and Observation (eg, list of diseases or lifestyle factors). Across the tools, these four elements were found in ≥75% of the tools along with Name (of the Family Member), Age at Onset (of the Observation), and Certainty and Negation of Observation. Five elements were found to be unique to a particular tool: Step Relationship, Foster Status, and Sex for the AMA's Adult Family History Form; Temporality of Observation (related to cigarette smoking) for the Utah Department of Health's FHH Toolkit; and Multiple Birth Status (responses to question ‘Was this person born a twin?’) for the U.S. Surgeon General's My Family Health Portrait.

Table 4:

Comparison of FHH elements across tools

| Element | Adult Family History Form | Cancer Family Tree | Colon Cancer Risk Assessment | Does It Run in the Family? Toolkit | Family Health History Toolkit | Family Health Link | Family Healthware | My Family Health Portrait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (19) | (10) | (9) | (19) | (14) | (10) | (11) | (22) | |

| Family member | ||||||||

| Side of family | ○ | ○ | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | |

| Family member | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Genetic relationship | ○ | • | ○ | |||||

| Half relationship | • | • | ○ | ○ | ○ | |||

| Step relationship | • | |||||||

| Adoptive status | • | • | ||||||

| Foster status | • | |||||||

| Multiple birth status | • | |||||||

| Name | • | • | • | • | • | • | ||

| Sex | • | |||||||

| Gender | • | • | • | |||||

| Place of birth | • | • | • | |||||

| Date of birth | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Current age | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Race | • | • | ||||||

| Ethnicity | • | • | • | |||||

| Ancestry | • | • | • | |||||

| Living status | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Date of death | • | • | • | |||||

| Age at death | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Cause of death | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Quantity of family member | • | • | • | |||||

| Observation | ||||||||

| Observation | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Observation type | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Age at onset | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Certainty of observation | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Negation of observation | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| Quantity of observation | • | • | ||||||

| Temporality of observation | • |

Elements for family members of patient only; some may also be collected for the patient in addition to other patient-specific elements.

(n) indicates total number of elements; • indicates explicit element; ○ indicates included due to values for Family Member or Observation.

FHH, family health history.

Intra-source comparison of data elements: specifications

A total of 37 elements were contributed by the FHH-related specifications from HL7, HITSP, AHIC, and openEHR that provided 26, 24, 24, and 18 elements, respectively (see online supplementary appendix D). Similar to the notes and tools, several elements were included based on potential values specified for Family Member. In particular, the HL7 Vocabulary for RoleCode included values such as ‘maternal grandparent,’ ‘natural child,’ ‘half sibling,’ ‘step child,’ ‘adopted child,’ ‘foster child,’ and ‘twin,’ thus resulting in the inclusion of Side of Family, Genetic Relationship, Half Relationship, Step Relationship, Adoptive Status, Foster Status, and Multiple Birth Status as elements for HL7. Elements common to all four organizations included: Family Member, Name, Gender, Date of Birth, Age at Death, Cause of Death, Observation, Observation Type (included due to values for Observation), and Age at Onset. Seven elements were found to be unique to a particular organization: Source of Information for HL7; Multiple Birth Order and Temporality of Observation (related to dates for genetic tests) for HITSP; and Quality of Relationship (eg, ‘estranged’ or ‘close’), Place of Birth, Partner Status, and Certainty of Family Member for AHIC.

Discussion

The results of this study highlight the value of multi-source development of an integrated model for FHH and provide guidance for the next steps. Through examination of multiple sources, a representative and complementary set of FHH data elements was identified. Compared with the first version of the Integrated FHH Model, the number of elements in the second version almost tripled, increasing from 16 to 44. The additional elements were related to demographics and relation types for family members, observation types and details, and general statements. Broader implications of this work include raising awareness of potential gaps in existing systems and documentation practices with various stakeholders (eg, developers of EHR systems and patient-facing FHH tools, standards development organizations, policy makers, and end-users such as clinicians and patients) for guiding enhancements that could ultimately lead to more comprehensive and standardized structured data entry of FHH.

Diversity in content and format was observed across the clinical notes, patient-facing FHH tools, and FHH-related specifications. While the integration process aimed to address many of these variations, there were some aspects and details that were not incorporated, which could be accommodated in future versions of the model and annotation schema for clinical text from EHR systems. For example, within the clinical notes, there were sentences including related or complex observations such as ‘pneumonia as a complication to Alzheimer disease’ or ‘blindness secondary to diabetic retinopathy’ that could be annotated in several ways (eg, as a single observation, two separate unlinked observations, or two separate linked observations). In addition, observations categorized as ‘Other’ suggest the need for additional categories such as General Health (eg, ‘healthy’ or ‘well’) and Exposure (eg, ‘second-hand smoke exposure’ or ‘positive asbestos exposure’) in addition to Disease, Procedure, Medication, and Lab Test. Further analysis and comparison of FHH documentation, in both structured and unstructured formats in the EHR, with respect to different roles and specialties (eg, primary care providers, prenatal care providers, oncologists, pharmacists, and medical geneticists and genetic counselors) or particular conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease and cancer) may be valuable for enhancing the general Integrated FHH Model with additional elements as well as informing the inclusion and priority of elements in context-specific implementations of the model.

Several tools included a response of ‘don't know’ or ‘unknown’ for questions suggesting the need to capture the certainty of other elements in addition to Certainty of Family Member and Certainty of Observation (eg, Certainty of Ancestry for ‘What best describes your birth mother's ancestry’ in Family HealthLink and Certainty of Living Status for ‘Living?’ in My Family Health Portrait). Other tools included questions such as ‘other information of significance’ in the AMA's Adult Family History Form and ‘other health concerns’ in Genetic Alliance's Does It Run in the Family? Toolkit where the free-text responses would need to be analyzed in order to determine if existing elements are sufficient or additional ones are needed. Finally, there were some tools that included detailed questions related to the social history of family members (eg, smoking status and amount, frequency of alcohol use, and frequency of vigorous routine exercise in the Utah Department of Health's FHH Toolkit) where the Integrated FHH Model could include elements that link to separate models for capturing details specific to different social, psychosocial, behavioral, and environmental factors (eg, alcohol use, drug use, living situation, marital status, occupation, residence, and tobacco use).81,82 There have been efforts by standards development organizations such as HL7 and openEHR to develop models for some of these factors that could be adopted and enhanced (eg, HL7 Tobacco Use Observation77 or openEHR archetypes for Alcohol Use and Alcohol Use Summary80).

Analysis of patient-specific questions in the FHH tools as well as additional general, specialty-specific, or condition-specific tools (eg, MeTree,48,49 OurFamilyHealth,54 Myriad Genetics Family History Tool,83 and March of Dimes FHH Form84) and specifications from national and international organizations (eg, Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC)85,86 and other HL7 implementation guides) could serve to further validate and enhance the Integrated FHH Model with additional elements. For example, while the two HL7 specifications reviewed in this study did not explicitly include elements for Partner Status and Multiple Birth Order, these are specified in the HL7 Reference Information Model (RIM) (maritalStatusCode in the HL7 Person class and multipleBirthOrderNumber in the HL7 Living Subject class).87

Other next steps include creating formal representations of the Integrated FHH Model in accordance with existing national and international information modeling initiatives (eg, Clinical Element Model (CEM) used by the Strategic Health IT Advanced Research Project for Secondary Use of EHR Data (SHARPn),88,89 Clinical Information Modeling Initiative (CIMI),90,91 and Federal Health Interoperability Modeling (FHIM) Initiative92). As part of this process, the model would be enhanced with clear definitions, attributes, cardinality, and value sets for each element. For example, across the sources, sex and gender93,94 as well as race, ethnicity, and ancestry95,96 were used interchangeably, which should be distinguished for appropriate use. For attributes, seed lists could be generated from those defined in existing specifications (eg, HL7 and AHIC) such as identifier, code, coding system, certainty, negation, status, and sensitivity. In addition, logic could be associated with particular elements that may be inferred or computed based on values for other elements to potentially minimize data entry effort (eg, if Family Member = ‘grandmother,’ then Sex = ‘female’ and Degree of Relationship = ‘second-degree relative’).

Analysis of the various sources in this study resulted in multiple lists of values for elements. For example, different lists of family members were observed across the tools (eg, the Cancer Family Tree tool had a list of seven types of relatives, while Family HealthLink included 20); varying lists for observations were generated from the notes (eg, 245 values categorized as diseases for MTS, 95 for UPMC, and 213 for FAHC); and different age and date formats were noted across the sources (eg, both specific and estimated ages such as ‘34,’ ‘30s,’ ‘30–39,’ and ‘young age’ for Age at Onset). A key part of the information model development process is alignment with terminologies, coding systems, data types, and units.97 Similar to the integration of data elements, efforts are needed to merge and map these values to standardized terminologies and coding systems such as those specified in the HL7 specifications examined in this work (eg, Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC),98 Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine—Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT),99 and HL7 V.3 Vocabulary and Data Types87,100) to support semantic interoperability.

Conclusion

There has been increased emphasis on the importance of FHH for supporting personalized medicine, biomedical research, and population health. The multi-source development of an integrated FHH model in this study contributes as an initiative for improving the standardized collection and use of FHH information in disparate systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katherine Kolor, PhD, MS, CGC from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing the Family Healthware tool for this research and feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. The authors also thank Kristin Baker Niendorf, MS, CGC from the University of Minnesota for contributing a list of cancer-related FHH tools and Rhonda Kost for assistance in obtaining the clinical notes for Fletcher Allen Health Care. Medical transcription reports were obtained with permission from MTSamples (http://www.mtsamples.com).

Contributors

ESC and GBM conceptualized the overall study design. GBM led development of the annotation schema, TJW and EWC annotated the clinical notes, EWC and ESC analyzed the tools, and TJW and ESC analyzed the specifications. INS contributed to the integration and mapping of data elements across sources as well as interpretation of results. YW provided support for the annotation of clinical notes, including development of scripts for processing the annotations. ESC compiled the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved with the consensus-based processes used for enhancing the annotation schema/guidelines and Integrated FHH Model, as well as reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01LM011364.

Competing interests

None.

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Vermont/Fletcher Allen Health Care and University of Minnesota.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available online at http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Guttmacher AE, Collins FS. Welcome to the genomic era. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:996–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rich EC, Burke W, Heaton CJ, et al. Reconsidering the family history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guttmacher AE, Collins FS, Carmona RH. The family history—more important than ever. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2333–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burke W. Taking family history seriously. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:388–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wattendorf DJ, Hadley DW. Family history: the three-generation pedigree. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:441–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olney RS, Yoon PW. Role of family medical history information in pediatric primary care and public health: introduction. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 2):S57–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trotter TL, Martin HM. Family history in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 2):S60–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hinton RB., Jr The family history: reemergence of an established tool. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20:149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valdez R, Yoon PW, Qureshi N, et al. Family history in public health practice: a genomic tool for disease prevention and health promotion. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:69–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Claassen L, Henneman L, Janssens AC, et al. Using family history information to promote healthy lifestyles and prevent diseases; a discussion of the evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Khoury MJ, Feero WG, Valdez R. Family history and personal genomics as tools for improving health in an era of evidence-based medicine. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:184–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pyeritz RE. The family history: the first genetic test, and still useful after all those years? Genet Med. 2012;14:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Welch BM, Kawamoto K. Clinical decision support for genetically guided personalized medicine: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:388–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moyer VA. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helfand M, Carson S. Screening for lipid disorders in adults: selective update of 2001 US Preventive Services Task Force Review [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 Jun. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK33494/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Lipid Disorders in Adults, Topic Page. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/lipid-disorders-in-adults-cholesterol-dyslipidemia-screening

- 17. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ginsburg GS, Willard HF. Genomic and personalized medicine: foundations and applications. Transl Res. 2009;154:277–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Public Health Genomics. Genomic Tests and Family History by Levels of Evidence. http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/gtesting/tier.htm

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Awareness of family health history as a risk factor for disease—United States, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:1044–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green RF. Summary of workgroup meeting on use of family history information in pediatric primary care and public health. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 2):S87–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scheuner MT, de Vries H, Kim B, et al. Are electronic health records ready for genomic medicine? Genet Med. 2009;11:510–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilson BJ, Carroll JC, Allanson J, et al. Family history tools in primary care: does one size fit all? Public Health Genomics. 2012;15:181–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peace J, Valdez RS, Lutz KF. Data-based considerations for electronic family health history applications. Comput Inform Nurs. 2012;30:37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Surgeon General's Family Health History Initiative. http://www.hhs.gov/familyhistory/

- 26. Family History Public Health Initiative. http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/famhistory/famhist.htm

- 27. Berg AO, Baird MA, Botkin JR, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Family History and Improving Health: August 24–26, 2009. NIH Consens State Sci Statements. 2009;26:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The American Society of Human Genetics, Genetic Alliance. Talk Health History Campaign. http://www.talkhealthhistory.org/

- 29. Yoon PW, Scheuner MT, Khoury MJ. Research priorities for evaluating family history in the prevention of common chronic diseases. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hulse NC, Taylor DP, Wood G, et al. Analysis of family health history data collection patterns in consumer-oriented Web-based tools. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings2008:982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hulse NC, Wood GM, Haug PJ, et al. Deriving consumer-facing disease concepts for family health histories using multi-source sampling. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43:716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giovanni MA, Murray MF. The application of computer-based tools in obtaining the genetic family history. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2010;Chapter 9:Unit 9.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peace J, Bisanar W, Licht N. Will family health history tools work for complex families? Scenario-based testing of a web-based consumer application. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:709–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feero WG. Connecting the dots between patient-completed family health history and the electronic health record. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1547–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoyt R, Linnville S, Chung HM, et al. Digital family histories for data mining. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2013;10:1a. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Murray MF, Giovanni MA, Klinger E, et al. Comparing electronic health record portals to obtain patient-entered family health history in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1558–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meaningful Use Stage 2—Family Health History. http://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/achieve-meaningful-use/menu-measures-2/family-health-history

- 38. Friedlin J, McDonald CJ. Using a natural language processing system to extract and code family history data from admission reports. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings2006:925. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goryachev S, Kim H, Zeng-Treitler Q. Identification and extraction of family history information from clinical reports. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings2008:247–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harkema H, Dowling JN, Thornblade T, et al. ConText: an algorithm for determining negation, experiencer, and temporal status from clinical reports. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:839–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou L, Lu Y, Vitale C, et al. Representation of information about family relatives as structured data in electronic health records. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5:349–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bill R, Pakhomov S, Chen ES, et al. Automated extraction of family history information from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014:(in press). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Surgeon General. My Family Health Portrait. https://familyhistory.hhs.gov

- 44. Facio FM, Feero WG, Linn A, et al. Validation of My Family Health Portrait for six common heritable conditions. Genet Med. 2010;12:370–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Owens KM, Marvin ML, Gelehrter TD, et al. Clinical use of the Surgeon General's “My Family Health Portrait” (MFHP) tool: opinions of future health care providers. J Genet Couns. 2011;20:510–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yoon PW, Scheuner MT, Jorgensen C, et al. Developing Family Healthware, a family history screening tool to prevent common chronic diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6:A33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang C, Sen A, Ruffin MT, et al. Family Healthware Impact Trial Group. Family history assessment: impact on disease risk perceptions. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:392–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Orlando LA, Buchanan AH, Hahn SE, et al. Development and validation of a primary care-based family health history and decision support program (MeTree). N C Med J. 2013;74:287–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Orlando LA, Hauser ER, Christianson C, et al. Protocol for implementation of family health history collection and decision support into primary care using a computerized family health history system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Orlando LA, Wu RR, Beadles C, et al. Implementing family health history risk stratification in primary care: impact of guideline criteria on populations and resource demand. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;166C:24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu RR, Himmel TL, Buchanan AH, et al. Quality of family history collection with use of a patient facing family history assessment tool. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Orlando LA, Henrich VC, Hauser ER, et al. The genomic medicine model: an integrated approach to implementation of family health history in primary care. Pers Med. 2013;15:295–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cohn WF, Ropka ME, Pelletier SL, et al. Health Heritage(c) a web-based tool for the collection and assessment of family health history: initial user experience and analytic validity. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:477–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hulse NC, Ranade-Kharkar P, Post H, et al. Development and early usage patterns of a consumer-facing family health history tool. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:578–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kush R, Goldman M. Fostering responsible data sharing through standards. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2163–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shabo A, Hughes K. Family history information exchange services using HL7 clinical genomics standard specifications. Int J Semantic Web Inform Syst. 2005;1:42065. [Google Scholar]

- 57. HL7 Version 3 Standard: Clinical Genomics; Pedigree, Release 1. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=8

- 58. HL7 Version 3 Implementation Guide: Family History/Pedigree Interoperability, Release 1—US Realm. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=301

- 59. Feero WG, Bigley MB, Brinner KM; Family Health History Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup of the American Health Information Community. New standards and enhanced utility for family health history information in the electronic health record: an update from the American Health Information Community's Family Health History Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:723–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Melton GB, Raman N, Chen ES, et al. Evaluation of family history information within clinical documents and adequacy of HL7 clinical statement and clinical genomics family history models for its representation: a case report. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:337–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Chen ES, Melton GB, Burdick TE, et al. Characterizing the use and contents of free-text family history comments in the Electronic Health Record. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:85–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. MTSamples. http://www.mtsamples.com/

- 63. Open Clinical Report Repository. http://neurolex.org/wiki/Category:Resource:Open_Clinical_Report_Repository

- 64. Fletcher Allen Health Care. http://www.fletcherallen.org/

- 65. General Architecture for Text Engineering (GATE). https://gate.ac.uk/

- 66. Stenetorp P, Pyysalo S, Topić G, et al. BRAT: a Web-based Tool for NLP-Assisted Text Annotation. Proceedings of the Demonstrations at the 13th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics2012:102–7. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Brat rapid annotation tool. http://brat.nlplab.org/

- 68. American Medical Association. Family Medical History. http://www.ama-assn.org//ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-science/genetics-molecular-medicine/family-history.page

- 69. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Office of Public Health Genomics. Family Health History. http://www.cdc.gov/genomics/famhistory/

- 70. University of Nebraska Medical Center. Cancer Family Tree. http://app1.unmc.edu/gencancer/

- 71. Cleveland Clinic. Colon Cancer Risk Assessment. http://digestive.ccf.org

- 72. Genetic Alliance. Does It Run in the Family? Toolkit. http://geneticalliance.org/programs/genesinlife/fhh

- 73. Utah Department of Health. Family Health History Toolkit. http://health.utah.gov/genomics/familyhistory/toolkit.html

- 74. The Ohio State University Medical Center. Family HealthLink. https://familyhealthlink.osumc.edu

- 75. Family Healthware. https://www.familyhealthware.com/

- 76. HL7 v3 Code System RoleCode. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/fhir/v3/RoleCode/index.html

- 77. HL7 Implementation Guide for CDA Release 2: IHE Health Story Consolidation, Release 1.1—US Realm. http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=258

- 78. HITSP/C154 HITSP Data Dictionary Component Version 1.0.1. http://www.hitsp.org/ConstructSet_Details.aspx?&PrefixAlpha=4&PrefixNumeric=154

- 79.Family Health History Multi-Stakeholder Workgroup Dataset Requirements Summary. http://hitsp.wikispaces.com/file/view/PHC_FamilyHData.pdf.

- 80. openEHR Clinical Knowledge Manager. http://www.openehr.org/ckm/

- 81. Chen ES, Manaktala S, Sarkar IN, et al. A multi-site content analysis of social history information in clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:227–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Melton GB, Manaktala S, Sarkar IN, et al. Social and behavioral history information in public health datasets. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2012;2012:625–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Myriad Genetics. Family History Tool. http://www.myriadpro.com/for-your-patients/family-history-tool/

- 84. March of Dimes. Family Health History Form. http://www.marchofdimes.com/materials/family-health-history-form.pdf

- 85. Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC). http://www.cdisc.org

- 86. Kush RD, Helton E, Rockhold FW, et al. Electronic health records, medical research, and the Tower of Babel. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1738–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. HL7. HL7 Reference Information Model (RIM). http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/rim.cfm

- 88. Pathak J, Bailey KR, Beebe CE, et al. Normalization and standardization of electronic health records for high-throughput phenotyping: the SHARPn consortium. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(e2):e341–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Clinical Element Models (CEMs). http://informatics.mayo.edu/sharp/index.php/CEMS

- 90. Clinical Information Modeling Initiative (CIMI). http://informatics.mayo.edu/CIMI

- 91. CIMI Browser. http://www.clinicalelement.com/cimi-browser

- 92. The Federal Health Information Model. http://www.fhims.org/

- 93. Short SE, Yang YC, Jenkins TM. Sex, gender, genetics, and health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 1):S93–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Doyal L. Sex and gender: the challenges for epidemiologists. Int J Health Serv. 2003;33:569–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ali-Khan SE, Krakowski T, Tahir R, et al. The use of race, ethnicity and ancestry in human genetic research. Hugo J. 2011;5:47–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rebbeck TR, Sankar P. Ethnicity, ancestry, and race in molecular epidemiologic research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(11 Pt 1):2467–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Chen ES, Zhou L, Kashyap V, et al. Early experiences in evolving an enterprise-wide information model for laboratory and clinical observations. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings2008:106–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes. http://loinc.org/

- 99. Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms. http://www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct/

- 100. HL7. HL7 Version 3 Namespaces (Code Systems and Value Sets). http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/fhir/terminologies-v3.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.