Abstract

Objective

To examine patient safety culture in Dutch out-of-hours primary care using the safety attitudes questionnaire (SAQ) which includes five factors: teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management and communication openness.

Design

Cross-sectional observational study using an anonymous web-survey. Setting Sixteen out-of-hours general practitioner (GP) cooperatives and two call centers in the Netherlands. Subjects Primary healthcare providers in out-of-hours services. Main outcome measures Mean scores on patient safety culture factors; association between patient safety culture and profession, gender, age, and working experience.

Results

Overall response rate was 43%. A total of 784 respondents were included; mainly GPs (N = 470) and triage nurses (N = 189). The healthcare providers were most positive about teamwork climate and job satisfaction, and less about communication openness and safety climate. The largest variation between clinics was found on safety climate; the lowest on teamwork climate. Triage nurses scored significantly higher than GPs on each of the five patient safety factors. Older healthcare providers scored significantly higher than younger on safety climate and perceptions of management. More working experience was positively related to higher teamwork climate and communication openness. Gender was not associated with any of the patient safety factors.

Conclusions

Our study showed that healthcare providers perceive patient safety culture in Dutch GP cooperatives positively, but there are differences related to the respondents’ profession, age and working experience. Recommendations for future studies are to examine reasons for these differences, to examine the effects of interventions to improve safety culture and to make international comparisons of safety culture.

Key Points

Creating a positive patient safety culture is assumed to be a prerequisite for quality and safety. We found that:

• healthcare providers in Dutch GP cooperatives perceive patient safety culture positively;

• triage nurses scored higher than GPs, and older and more experienced healthcare professionals scored higher than younger and less experienced professionals – on several patient safety culture factors; and

• within the GP cooperatives, safety climate and openness of communication had the largest potential for improvement.

Keywords: Patient safety culture, safety attitudes, adverse events, primary care, after-hours

Introduction

It is believed that reform of organisational structures, clinical training, guidelines and information technology are not sufficient to achieve good quality and patient safety in healthcare. Creating a positive patient safety culture is assumed to be a prerequisite for quality and safety. The culture of an organisation consists of the shared norms, values, behaviour patterns, rituals and traditions of its employees [1]. Safety culture is an aspect of the organisational culture. It is how leader-and-staff-interaction, attitudes, routines and practices protect patients from adverse events in healthcare [2]. Safety culture exists in groups of people working together and not only in individuals [3,4].

For many years patient safety – and safety culture – was mainly studied in the hospital care setting [5,6]. In recent years, there has also been an increasing interest in patient safety in primary care, as most patients receive their healthcare in primary care settings, particularly in countries with a strong primary care system [7]. In several European countries, including the Netherlands, primary care outside office hours is provided by large-scale general practitioner (GP) cooperatives [8–10]. In these out-of-hours GP cooperatives, patient safety is of particular importance, because of a high patient throughput, diversity of urgent clinical conditions presented, identification of medical urgency during telephone contacts and limited knowledge of the medical history of the patient. In addition, the GPs work in shifts and have to collaborate with other healthcare providers, which increase the risk of errors caused by discontinuity in information transfer [11,12]. Table 1 gives an overview of the general characteristics of Dutch GP cooperatives.

Table 1.

| Theme | Feature |

|---|---|

| Organisation | Since the year 2000, after-hours primary care has been provided by large-scale primary care physician cooperatives in the Netherlands. |

| There are about 120 primary care physician cooperatives. | |

| After-hours is defined as from 5 pm to 8 am on weekdays and all hours on weekends and in holidays. | |

| A primary care physician cooperative serves a population of 100,000–500,000 patients with an average care consumption of 250/1000 inhabitants per year. | |

| 50–250 primary care physicians participate in a cooperative, with a mean of 4 h on call per week. | |

| A shift takes 6–8 h, with an hourly salary of 65 Euros. | |

| Per shift, primary care physicians have different roles: supervising telephone triage, doing centre consultations, making home visits or a combination of these roles. | |

| Location | Primary care physician cooperatives are usually situated in or near a hospital’s emergency department. |

| The distance any patient is away from a primary care physician cooperative is 30 km at most. | |

| Accessibility | Access through a single regional telephone number. |

| Telephone triage by nurses supervised by primary care physicians: contacts are divided into telephone advice (by triage nurse or physician), primary care physician clinic consultation, or primary care physician home visit. | |

| Some primary care physician cooperatives use a central call centre for telephone triage. | |

| Facilities | Home visits are supported by trained drivers in identifiable fully equipped cars (e.g. oxygen, intravenous drip equipment, automated external defibrillator and medication for acute treatment). |

| Information and communication technology (ICT) support, including electronic patient records, online connections with primary care physician cars and connections with electronic medical records in primary care daytime practices. |

Several instruments are available to assess safety culture [13,14]. One of them is the safety attitudes questionnaire (SAQ), which is the most commonly used instrument to measure patient safety culture in hospital operating rooms [15]. The instrument may identify possible weaknesses in a clinical setting and this can stimulate quality improvement interventions [16]. SAQ scores have been found to correlate with patient outcomes [13,17,18] and the SAQ has been demonstrated to be a useful instrument for measuring the effects over time of interventions on patient safety culture [19,20]. From the original hospital SAQ, a questionnaire for measuring safety culture in outpatient settings was developed, adjusted to and tested in the primary care setting [21]. This ambulatory version of the SAQ (SAQ-AV) has already been validated in the UK [21], Norway [22] and Slovenia [23], including out-of-hours primary care services in the latter two countries. The Dutch translated version of the SAQ-AV for out-of-hours GP cooperatives has recently been validated, and includes five major patient safety factors: teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management and communication openness [24].

The aim of this study was to examine patient safety culture in Dutch GP cooperatives. We wanted to study whether variations in safety culture are related to professional background, gender, age and working experience of the healthcare providers.

Materials and methods

Setting

The study was performed in a convenience sample of 16 out-of-hours GP cooperatives and two call centres in the Netherlands. The two call centres performed the telephone triage of all calls to seven of the 16 GP cooperatives. The clinics were spread over the East, South and West of the Netherlands and varied in size and urbanisation grade. They served a total population of 2,050,000 inhabitants.

Subjects

The GP cooperatives employed a total of 2015 healthcare professionals, of whom 76.2% GPs, 15.9% triage nurses and 7.9% other personnel. Locum doctors who had worked less than five shifts during the past year and professionals without direct patient contact in their clinical work were excluded from the study.

Questionnaire

The SAQ-AV contains 62 items on patient safety culture. Respondents rate their agreement on a five-point Likert scale. For all questions, ‘not applicable’ was included as a response category. In addition, the SAQ-AV contains background items; e.g. the respondent’s profession and number of years of experience.

We used the Dutch version of the SAQ-AV. In a previous publication, we examined the psychometric properties of the questionnaire [24]. The Dutch SAQ-AV has five factors covering 27 items: teamwork climate, safety climate, job satisfaction, perceptions of management, and communication openness. The reliability scores (Cronbach’s alpha) of the factors were between 0.49 and 0.86 and the construct validity was good [24]. In this study, we analysed only the 27 items of the SAQ-AV that belong to the Dutch factor structure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of items within each factor of the SAQ-AV.

| Item |

|---|

| Perceptions of management |

| Senior management of this office is doing a good job |

| The management of this office supports my daily efforts |

| Decision making in this office utilizes input from relevant personnel |

| Medical errors are handled appropriately in this office |

| This office deals constructively with problem personnel |

| Disagreements in this office are resolved appropriately (i.e. not who is right but what is best for the patient) |

| This office does a good job of training new personnel |

| Nurse input is well received in this office |

| I am provided with adequate, timely information about events in the office that might affect my work |

| Job satisfaction |

| This office is a good place to work |

| I like my job |

| I feel frustrated by my job |

| I am proud to work in this office |

| Working in this office is like being part of a large family |

| Teamwork climate |

| Attending physicians/primary care providers in this office are doing a good job |

| It is easy for personnel in this office to ask questions when there is something that they do not understand |

| The physicians and nurses here work together as a well-coordinated team |

| I have the support I need from other personnel to care for patients |

| Trainees in my discipline are adequately supervised |

| Important issues are well communicated at shift changes |

| Safety climate |

| During emergencies, I can predict what other personnel are going to do next |

| I am encouraged by my colleagues to report any patient safety concerns I may have |

| The culture in this office makes it easy to learn from the errors of others |

| I know the proper channels to direct questions regarding patient safety in this office |

| Communication openness |

| In the office, it is difficult to speak up if I perceive a problem with patient care |

| In this office, it is difficult to discuss errors |

| I am frequently unable to express disagreement with staff physicians/intensivists in this office |

Data collection

In January and February 2015, the SAQ-AV was distributed by a link in an e-mail to all 2015 primary healthcare providers in the 16 participating GP cooperatives and two participating call centres. Data were collected electronically using the programme Qualtrics, Provo, UT whereby the participants responded anonymously. Two reminders were sent. Participation was voluntary. All participants received written information about the purpose of the study, and that the data were collected anonymously and treated with confidence.

The study was a project of the European research network for out-of-hours primary health care (EurOOHnet) [25]. This international SAFE-EUR-OOH project was also performed in Norway (coordinating country) [22,26], Slovenia [23,27,28], Italy and Croatia. The translation and data collection procedures were equal in each country [22–24].

Statistical analyses

The Qualtrics file with anonymous SAQ-AV data was converted into an SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) file for further analysis (IBM SPSS 22, Armonk, NY). Of the respondents, 69 (8.1%) were excluded because they had completed less than half of all safety culture items – they all prematurely ended the questionnaire.

The response category ‘not applicable’ was treated as a missing value in the data analyses (0–2% missing values per item). Since, the questionnaire contains positively as well as negatively worded items, the negatively formulated items were first recoded to make sure that a higher score always meant a more positive response. To calculate 100-point scale scores for each respondent, the mean of the set of items within each of the five factors was calculated, one was subtracted from the mean, and the result was multiplied by 25 [29].

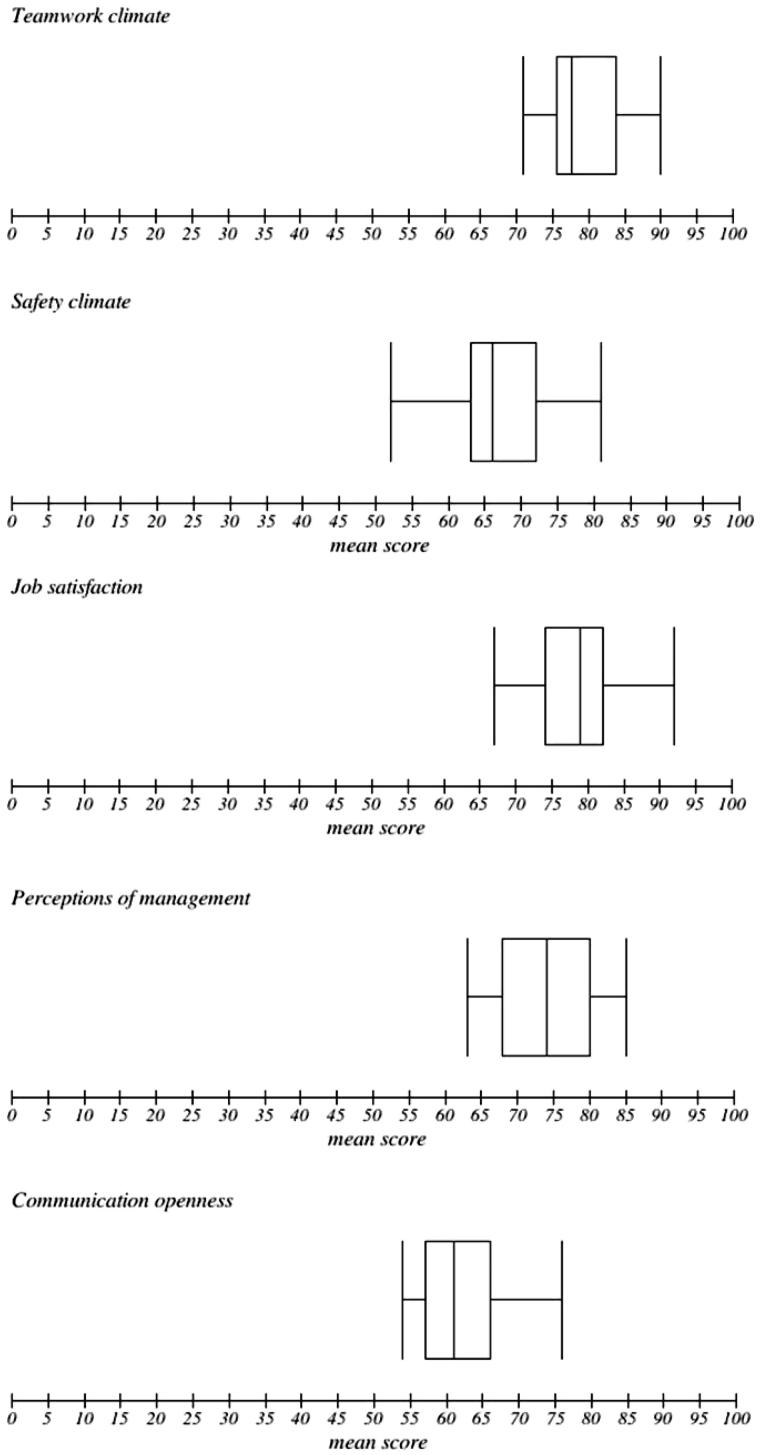

Descriptive analyses were performed; for each factor, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for the total group, and for subgroups of profession, gender, age and working experience. For each factor, a multilevel linear regression analysis (mixed models) was performed to examine if patient safety culture was related to professional background, gender, age and working experience. Finally, box-and-whisker plots were made for each patient safety factor, to examine the variation in mean scores between clinics.

Results

Characteristics of the respondents

Of the 2015 employed healthcare professionals, 1974 (98.0%) correctly received an invitation to complete the questionnaire on a working email address, of which 853 (43.2%) answered the questionnaire. Analyses were performed on the 784 (39.7%) respondents who answered more than half of the patient safety culture items within each factor. Of the respondents, 526 (68.6%) were female and 233 (30.4%) were aged between 41 and 50 years. Most of the respondents were GPs (61.2%; N = 470) or triage nurses (24.6%; N = 189). The largest group had been working at the current GP cooperative for 11–20 years (36.0%; N = 276) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of the respondents.

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Profession (N = 768) | |

| GP | 470 (61.2) |

| Triage nurse | 189 (24.6) |

| Driver | 39 (5.1) |

| Specialised nurse | 24 (3.1) |

| Administrator | 21 (2.7) |

| Gender (N = 767) | |

| Female | 526 (68.6) |

| Age (N = 767) | |

| ≤30 y | 95 (12.4) |

| 31–40 years | 196 (25.6) |

| 41–50 years | 233 (30.4) |

| 51–60 years | 194 (25.3) |

| ≥61 years | 49 (6.4) |

| Working experiencea (N = 767) | |

| ≤2 years | 136 (17.7) |

| 3–5 years | 168 (21.9) |

| 6–10 years | 187 (24.4) |

| ≥11 years | 276 (36.0) |

At current GP cooperative/call centre.

Patient safety culture

The mean scores for the five patient safety factors – by profession, gender, age and working experience – are presented in Table 4. The highest mean factor scores were on teamwork climate (79.2) and job satisfaction (79.0), whereas the lowest mean scores were on communication openness (61.5) and safety climate (68.1). Multilevel linear regression analysis showed some significant differences between subgroups of respondents. Triage nurses scored significantly higher than GPs on each of the five safety culture factors. In addition, nurses scored significantly higher on perceptions of management and communication openness than the group of other professions (drivers, specialised nurses and administrators) and there was a similar – although not significant – tendency on the other factors. Older healthcare providers scored significantly higher than younger on safety climate and perceptions of management. Healthcare providers with more working experience scored significantly higher on teamwork climate and communication openness. There were no significant differences in mean factor scores between male and female healthcare providers.

Table 4.

Mean factor scores by profession, gender, age and working experience (N = 784).

| Factor | N | Mean (SD) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork climate | |||

| Total | 784 | 79.2 (13.6) | – |

| Profession | |||

| Triage nurse (ref) | 189 | 82.8 (13.1) | – |

| GP | 470 | 77.9 (13.6) | .00 |

| Other | 109 | 80.1 (12.5) | .37 |

| Gender | – | – | .46 |

| Female | 526 | 79.4 (13.7) | – |

| Male | 241 | 79.2 (12.8) | – |

| Age (years) | – | – | .17 |

| ≤30 | 95 | 76.5 (12.5) | – |

| 31–40 | 196 | 77.6 (13.4) | – |

| 41–50 | 233 | 79.9 (13.3) | – |

| 51–60 | 194 | 81.4 (14.2) | – |

| ≥61 | 49 | 81.5 (11.6) | – |

| Working experience (years) | – | – | .05 |

| ≤2 | 136 | 77.9 (12.4) | – |

| 3–5 | 168 | 77.0 (13.9) | – |

| 6–10 | 187 | 79.3 (13.6) | – |

| ≥11 | 276 | 81.6 (13.3) | – |

| Safety climate | |||

| Total | 784 | 68.1 (16.3) | – |

| Profession | |||

| Triage nurse (ref) | 189 | 73.5 (14.1) | – |

| GP | 470 | 65.4 (16.2) | .00 |

| Other | 109 | 70.1 (17.9) | .27 |

| Gender | – | – | .29 |

| Female | 526 | 68.1 (16.3) | – |

| Male | 241 | 67.7 (16.4) | – |

| Age (years) | – | – | .04 |

| ≤30 | 95 | 65.0 (17.9) | – |

| 31–40 | 196 | 64.7 (15.1) | – |

| 41–50 | 233 | 68.4 (16.3) | – |

| 51–60 | 194 | 72.0 (16.4) | – |

| ≥61 | 49 | 69.1 (14.2) | – |

| Working experience (years) | – | – | .06 |

| ≤2 | 136 | 65.4 (17.1) | – |

| 3–5 | 168 | 65.6 (15.9) | – |

| 6–10 | 187 | 68.5 (15.8) | – |

| ≥11 | 276 | 70.5 (16.2) | – |

| Job satisfaction | |||

| Total | 784 | 79.0 (17.1) | – |

| Profession | |||

| Triage nurse (ref) | 189 | 88.9 (11.8) | – |

| GP | 470 | 73.3 (17.3) | .00 |

| Other | 109 | 87.3 (11.2) | .43 |

| Gender | – | – | .25 |

| Female | 526 | 80.2 (16.7) | – |

| Male | 241 | 76.6 (17.4) | – |

| Age (years) | – | – | .25 |

| ≤ 30 | 95 | 78.9 (15.1) | – |

| 31–40 | 196 | 76.5 (16.7) | – |

| 41–50 | 233 | 78.2 (18.3) | – |

| 51–60 | 194 | 81.0 (16.9) | – |

| ≥61 | 49 | 86.2 (13.1) | – |

| Working experience (years) | – | – | .31 |

| ≤2 | 136 | 79.8 (16.0) | – |

| 3–5 | 168 | 78.3 (16.8) | – |

| 6–10 | 187 | 78.9 (17.0) | – |

| ≥11 | 276 | 79.3 (17.7) | – |

| Perceptions of management | |||

| Total | 784 | 73.4 (15.8) | – |

| Profession | |||

| Triage nurse (ref) | 189 | 78.0 (15.2) | – |

| GP | 470 | 72.0 (15.4) | .00 |

| Other | 109 | 71.4 (17.5) | .01 |

| Gender | – | – | .80 |

| Female | 526 | 73.7 (15.8) | |

| Male | 241 | 72.7 (16.0) | |

| Age (years) | – | – | .05 |

| ≤30 | 95 | 74.0 (14.0) | – |

| 31–40 | 196 | 69.8 (15.3) | – |

| 41–50 | 233 | 73.5 (16.4) | – |

| 51–60 | 194 | 76.0 (16.8) | – |

| ≥61 | 49 | 75.5 (13.1) | – |

| Working experience (years) | – | – | .87 |

| ≤2 | 136 | 74.5 (14.0) | – |

| 3–5 | 168 | 69.6 (15.2) | – |

| 6–10 | 187 | 72.2 (16.4) | – |

| ≥11 | 276 | 75.8 (16.4) | – |

| Communication openness | |||

| Total | 784 | 61.5 (21.3) | – |

| Profession | |||

| Triage nurse (ref) | 189 | 68.1 (19.1) | – |

| GP | 470 | 59.4 (21.4) | .00 |

| Other | 109 | 59.2 (22.7) | .00 |

| Gender | – | – | .11 |

| Female | 526 | 61.2 (20.8) | – |

| Male | 241 | 62.0 (22.5) | – |

| Age (years) | – | – | .59 |

| ≤30 | 95 | 53.6 (23.8) | – |

| 31–40 | 196 | 60.7 (19.4) | – |

| 41–50 | 233 | 62.3 (20.3) | – |

| 51–60 | 194 | 64.7 (21.8) | – |

| ≥61 | 49 | 63.4 (23.4) | – |

| Working experience (years) | – | – | .00 |

| ≤2 | 136 | 56.3 (23.8) | – |

| 3–5 | 168 | 58.5 (19.5) | – |

| 6–10 | 187 | 63.2 (19.2) | – |

| ≥11 | 276 | 64.7 (21.8) | – |

p Value obtained from multilevel linear regression analysis adjusting for the other background characteristics (profession, gender, age >40 years and working experience >5 years) and clustering effects of clinics. p values <.05 indicating statistical significance in bold.

Variation between clinics

Figure 1 shows the variation between clinics for each of the five factors. The largest range between clinics was on safety climate (lowest mean score 51.6; highest 81.3), whereas the lowest variation was on teamwork climate (lowest mean score 70.8; highest 90.0). The largest interquartile range was on perceptions of management (11.6), and the lowest on job satisfaction (8.2) and teamwork climate (8.2). Communication openness showed the highest skewness. There were no outliers: values that lay more than one and a half times the length of the box from either end of the box.

Figure 1.

Variation in mean factor scores between clinics (N = 17). Boxplots: the left and right side of the box are the first and third quartiles; the band inside the box is the median (second quartile); the ends of the whiskers represent the minimum and maximum score.

Discussion

Principle findings

Healthcare providers in Dutch out-of-hours GP cooperatives are most positive about teamwork climate and job satisfaction and the least about communication openness. Safety climate has the highest improvement potential, because of a rather low mean score on this factor and a large variation between clinics. There were significant differences between respondents with a different professional background, age and working experience. Triage nurses scored significantly higher than GPs on each of the five patient safety culture factors. They also scored significantly higher than the group of other professions on perceptions of management and communication openness. Older healthcare providers scored significantly higher than younger on safety climate and perceptions of management. Finally, having more years of working experience at the GP cooperative was positively related to higher scores on teamwork climate and communication openness. Gender was not related to any of the patient safety factors.

Strengths and weaknesses

Strength of this study is that it was performed in a large group of GP cooperatives, resulting in a large sample to be used in our analyses. The GP cooperatives were spread across the country, with the exception of the low urbanised Northern area. It is unclear whether this has influenced the results. Overall, the GP cooperatives varied in size and degree of urbanisation, contributing to the representativeness of the sample. The participating GP cooperatives together served 13% of the Dutch population. In addition, this is the first study to use the Dutch version of the SAQ-AV in primary care. The response rate was 43%, which is below the recommended response rate of 60% in patient safety culture research [30]. In the Norwegian study using the SAQ-AV, the response rate was 51%, but that study also included GP practices, to which GPs are more closely linked than to the OOH service [26]. We could not perform a non-response bias analysis, but the results indicate that GPs were somewhat underrepresented. Of the respondents, 61% were GPs, but among the invited employees 76% were GPs. Triage nurses were overrepresented of the respondents 25% were triage nurses, but among the invited employees 16% were triage nurses. The background characteristics of the GPs who responded were comparable to those of the national GP population in terms of age, gender and working status (settled in a general practice or not), although the respondents were slightly younger and more often female [31].

Comparison with previous studies

Overall, healthcare providers perceive patient safety culture in Dutch GP cooperatives positively. This was also found in a previous study in Dutch primary care practices using an adapted version of the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture [32]. Similar to our results, a previous study in Norwegian out-of-hours clinics showed that nurses and older employees scored higher on the SAQ-AV [26]. This finding might be due to a larger attachment of these groups to their own working place. Most triage nurses spend all their working hours in the GP cooperative, while most of the GPs have out-of-hours duty as a limited activity in addition to working as a GP in their daytime general practice [26]. Contrary to the Norwegian study, we also examined the influence of working years at the GP cooperative, next to age, as many triage nurses start working at a GP cooperative at a higher age. Employees who have worked in GP cooperatives for a long period will most likely feel more comfortable in that clinical setting and are therefore more positive about the safety culture [26].

Implications

The openness of communication and safety climate in Dutch GP cooperatives could be improved. Communication openness includes, for example the perceived difficulty to discuss errors, to express disagreement or to speak up if one sees a problem with patient care. Patient safety culture questionnaires can act as an intervention to improve communication openness, especially when accompanied by a practice workshop enhancing the interaction of team members and creation of shared goals [33]. Communication openness might also be stimulated by blame-free incident reporting. To enable healthcare providers to improve their quality of care, reporting should be non-punitive, confidential or anonymous, independent, timely, systems-oriented and responsive [34].

Safety climate includes the predictability of the behaviour of other personnel, encouragement by colleagues to report patient safety concerns and easiness to learn from errors of others. Safety climate might be enhanced by team training interventions [35], which have the potential to facilitate learning and create a sustainable culture of patient safety [36].

Future studies should explore possible reasons for the differences found between healthcare professionals, and examine if there is an association between patient safety culture, patient experiences and the occurrence of adverse events in GP cooperatives. In addition, studies evaluating the effects of interventions focusing on improvement of communication openness or safety climate are recommended, preferably using a pre-post design. Finally, previous research has shown differences across countries in hospital patient safety culture [37]. It is interesting to examine if countries differ in their scores on the SAQ-AV; indicating differences in patient safety culture in primary care.

Conclusions

Our study showed that healthcare providers perceive patient safety culture in Dutch GP cooperatives positively. Triage nurses scored higher than GPs, older healthcare professionals scored higher than younger and experienced healthcare professionals scored higher than inexperienced – on several patient safety culture factors. Recommendations for future studies are to examine reasons for these differences, to examine the effects of interventions to improve safety culture and to make international comparisons of patient safety culture.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the participating GP cooperatives.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Research Committee concluded that this study does not fall within the remit of the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act [Wet Mensgebonden Onderzoek] (file number 2014-299).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Notes on contributors

Marleen Smits, PhD, post doctoral researcher at Radboud Scientific Center for Quality of Healthcare (IQ healthcare), Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands and Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Ellen Keizer, PhD student at Radboud Scientific Center for Quality of Healthcare (IQ healthcare), Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Paul Giesen, MD, PhD, general practitioner and senior researcher at Radboud Scientific Center for Quality of Healthcare (IQ healthcare), Radboud university medical center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Ellen Catharina Tveter Deilkås, MD, PhD, senior researcher at Health Services Research Unit, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog, Norway and senior advisor at The Norwegian Directorate of Health, Oslo, Norway.

Dag Hofoss, PhD, professor emeritus at Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.

Gunnar Tschudi Bondevik, MD, PhD, general practitioner and professor at Department of Global Public Health and Primary Care, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway and principal researcher at National Centre for Emergency Primary Health Care, Uni Research Health, Bergen, Norway

References

- 1.Schein E. Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deilkås ET. Patient safety culture-opportunities for healthcare management [PhD thesis]. Norway: University of Oslo; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smits M, Wagner C, Spreeuwenberg P, et al. Measuring patient safety culture: an assessment of the clustering of responses at unit level and hospital level. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deilkås ET, Hofoss D.. Patient safety culture lives in departments and wards: multilevel partitioning of variance in patient safety culture. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, et al. The incidence and nature of in/hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vlayen A, Verelst S, Bekkering GE, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse events requiring intensive care admission: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2012;18:485–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Berg MJ, van Loenen T, Westert GP.. Accessible and continuous primary care may help reduce rates of emergency department use. An international survey in 34 countries. Fam Pract. 2016;33:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huibers L, Giesen P, Wensing M, et al. Out-of-hours care in western countries: assessment of different organizational models. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giesen P, Smits M, Huibers L, et al. Quality of after-hours primary care in the Netherlands: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smits M, Rutten M, Keizer E, et al. The development and performance of after-hours primary care in the Netherlands: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:737–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giesen P, Ferwerda R, Tijssen R.. Safety of telephone triage in general practitioner cooperatives: do triage nurses correctly estimate urgency? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:181–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smits M, Huibers L, Kerssemeijer B, et al. Patient safety in out-of-hours primary care: a review of patient records. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colla JB, Bracken AC, Kinney LM, et al. Measuring patient safety climate: a review of surveys. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:364–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flin R, Burns C, Mearns K, et al. Measuring safety climate in health care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:109–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao P, Li Y, Li Z, et al. Use of patient safety culture instruments in operating rooms: a systematic literature review. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel CA, et al. Creating high reliability in health care organizations. Health Serv Res. 2006;41:1599–1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deilkås ET, Hofoss D.. Psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ), generic version (short form 2006). BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiCuccio MH. The relationship between patient safety culture and patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Patient Saf. 2015;11:135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristensen S, Christensen KB, Jaquet A, et al. Strengthening leadership as a catalyst for enhanced patient safety culture: a repeated cross-sectional experimental study. BMJ Open. 2016; 6:e010180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGuire MJ, Noronha G, Samal L, et al. Patient safety perceptions of primary care providers after implementation of an electronic medical record system. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Modak I, Sexton JB, Lux TR, et al. Measuring safety culture in the ambulatory setting: the safety attitudes questionnaire–ambulatory version. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bondevik GT, Hofoss D, Holm Hansen E, et al. The safety attitudes questionnaire-ambulatory version: psychometric properties of the Norwegian translated version for the primary care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemenc-Ketis Z, Maletic M, Stropnik V, et al. The safety attitudes questionnaire–ambulatory version psychometric properties of the Slovenian version for the out-of-hours primary care setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smits M, Keizer E, Giesen P, et al. The psychometric properties of the ‘Safety Attitudes Questionnaire’ in Dutch out-of-hours primary care services. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huibers L, Philips H, Giesen P, et al. EurOOHnet-the European research network for out-of-hours primary health care. Eur J Gen Pract. 2014;20:229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bondevik GT, Hofoss D, Holm Hansen E, et al. Patient safety culture in Norwegian primary care: a study in out-of-hours casualty clinics and GP practices. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2014;32:132–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klemenc-Ketis Z, Deilkås ET, Hofoss D, et al. Patient safety culture in Slovenian out-of-hours primary care clinics. Zdr Varst. 2017;56:203–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klemenc-Ketis Z, Deilkås ET, Hofoss D, et al. Variations in patient safety climate and perceived quality of collaboration between professions in out-of-hours care. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scale computation instruction. Houston, Texas: McGovern Medical School, 2015. Available from: https://med.uth.edu/chqs/files/2015/12/Scale-Computation-Instructions-updated-EWS-12.23.15.pdf (accessed 26 July 2017).

- 30.Pronovost P, Sexton B.. Assessing safety culture: guidelines and recommendations. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:231–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Hassel D, Kasteleijn A, Kenens R.. Cijfers uit de registratie van huisartsen: peiling 2015. [Data from registration on general practitioners. Measurements 2015]. Utrecht (The Netherlands): NIVEL; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verbakel N, van Melle M, Langelaan M, Verheij T, et al. Exploring patient safety culture in primary care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Verbakel N, de Bont A, Verheij T, et al. Improving patient safety culture in general practice: an interview study. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65:e822–e828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leape LL. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1633–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weaver SJ, Dy SM, Rosen MA.. Team-training in healthcare: a narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23:359–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandstorp H, Halvorsen PA, Sterud B, et al. Primary care emergency team training in situ means learning in real context. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34:295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wagner C, Smits M, Sorra J, et al. Assessing patient safety culture in hospitals across countries. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25:213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]