Abstract

Background and purpose

Dual-mobility cups (DMCs) reduce the risk of dislocation and porous tantalum (TM) shells show favorable osseointegration after acetabular revision surgery, yet the combination of these implants has not been studied. We hypothesized that (1) cementing a DMC into a TM shell decreases the risk of dislocation; (2) DMCs cemented into TM shells are not at greater risk of re-revision; (3) liberation of tantalum ions is marginal after use of this combined technique.

Patients and methods

We investigated the outcome in 184 hips (184 patients) after acetabular revision surgery with TM shells, fitted either with DMCs (n = 69), or with standard polyethylene (PE) liners (n = 115). Chart follow-up was complete for all patients, and the occurrence of dislocations and re-revisions was recorded. 20 were deceased, 50 were unable to attend follow-up, leaving 114 for assessment of hip function after 4.9 (0.5–8.9) years, radiographs were obtained in 99, and tantalum concentrations in 84 patients.

Results

1 patient with a DMC had a dislocation, whereas 14 patients with PE liners experienced at least 1 dislocation. 11 of 15 re-revisions in the PE group were necessitated by dislocations, whereas none of the 2 re-revisions in the DMC group was performed for this reason. Hence, dislocation-free survival after 4 years was 99% (95% CI 96–100) in the DMC group, whereas it was 88% (CI 82–94, p = 0.01) in the PE group. We found no radiographic signs of implant failure in any patient. Mean tantalum concentrations were 0.1 µl/L (CI 0.05–0.2) in the DMC group and 0.1 µg/L (CI 0.05–0.2) in the PE group.

Interpretation

Cementing DMCs into TM shells reduces the risk of dislocation after acetabular revision surgery without jeopardizing overall cup survival, and without enhancing tantalum release.

Dislocation after hip revision surgery occurs in between 3 and 10% of patients (Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register 2016). It is the most common reason for re-revision after hip revision surgery during the first 2 years, accounting for 35% of all re-revisions (Springer et al. 2009). Porous tantalum (TM) shells perform well in hip revision surgery, with a low risk of re-revision due to aseptic loosening, but dislocation seems to be an issue after the use of this device (Lakstein et al. 2009, Skyttä et al. 2011, Borland et al. 2012, Kremers et al. 2012, Batuyong et al. 2014, Beckmann et al. 2014, Mohaddes et al. 2015, Konan et al. 2016, Brüggemann et al. 2017).

Dual-mobility cups (DMCs) reduce the risk of dislocation after revision hip surgery (Hailer et al. 2012, Gonzalez et al. 2017), and DMCs cemented into TM shells have occasionally been used in an attempt at reducing the risk of dislocation after hip revision surgery, with seemingly satisfactory results (Brüggemann et al. 2017). On the other hand, concerns related to the stability of the DMC inside a TM shell remain, and the concept of cementing DMCs into TM shells has not been systematically investigated.

Very little is known regarding the liberation of tantalum ions from TM shells, apart from 1 case report by Babis et al. (2014) that describes grossly elevated serum levels of tantalum after failed revision making use of a TM device. The tantalum concentration in that case was 20 µg/L, which is much higher than the reference interval of 0.008–0.010 µg/L that is derived from a healthy population without implants (Rodushkin et al. 2004). The question remains whether measurable tantalum liberation occurs after the use of TM shells, either from the interface between a DMC and the TM shell, or from the TM-bone interface.

We hypothesized that cementing a DMC into a TM shell decreases instability. We further hypothesized that cementing of DMCs into TM shells results in a stable construct, and does not lead to increased tantalum ion release when compared with standard PE liners within a TM shell.

Patients and methods

Implant survival and dislocation rates

We identified all acetabular revisions using a TM shell (Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN) during 2008–2016 in our local arthroplasty register. Whenever a patient had revision in both hips, only the hip that was revised first was included (Ranstam et al. 2011). 184 hips were thus included, and we divided this cohort into 2 subgroups. DMC group: 69 hips were treated with a DMC (Avantage; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN) cemented into a larger TM shell (TM Modular, Trilogy TM or TM Revision shell, Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN). PE group: 115 hips received a standard polyethylene (PE) liner inside a TM shell, either as a standard snap-fit liner when a smaller TM shell was used (Continuum, TM Modular, or Trilogy TM; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN), or a PE liner cemented into a larger TM shell (TM Modular, Trilogy TM, or TM Revision shell; Zimmer Biomet, Warsaw, IN). PE liners were cemented according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To ensure that no dislocations treated with closed reduction went unnoticed, we accessed all patient charts and searched charts for all closed reductions, thus ensuring complete chart follow-up for all patients.

Radiographs

Acetabular defect size prior to the index procedure was assessed using the Paprosky classification for all but 1 hip by analyzing radiographs obtained prior to the index procedure (Paprosky et al. 1994). 2 observers (AB, EK) analyzed standard anteroposterior pelvic radiographs and classified bone loss. When in disagreement, consensus was reached under the guidance of the senior author (NPH). We assessed cup migration at follow-up using the method described by Nunn et al. (1989).

Characteristics of the study population

There were 94 females and 90 males with a mean age of 67 (35–88) years. The main reason for the index procedure was aseptic loosening in both groups. There was a difference between the DMC group and the PE group regarding the severity of the acetabular defects, with a higher proportion of Paprosky grade III A and B defects in the DMC group. Reasons for the index procedure and number of revisions prior to the index procedure were similar between groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study population

| PE (n = 115) | DMC (n = 69) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||

| Male | 56 | 34 |

| Female | 59 | 35 |

| Paprosky: | ||

| I | 22 | 5 |

| IIA | 16 | 10 |

| IIB | 19 | 9 |

| IIC | 28 | 8 |

| IIIA | 12 | 18 |

| IIIB | 17 | 19 |

| Reason for index procedure: | ||

| Loosening | 98 | 56 |

| Dislocation | 3 | 2 |

| Infection | 6 | 6 |

| Other | 8 | 5 |

| Number of revisions: | ||

| First-time revision | 88 | 46 |

| Previously revised | 27 | 23 |

| Bone graft: | ||

| No | 84 | 49 |

| Yes | 26 | 16 |

| Augments: | ||

| 0 | 109 | 57 |

| 1 | 4 | 11 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Stem revised at index procedure: | ||

| No | 78 | 43 |

| Yes | 37 | 26 |

Note: We found only a statistically significant difference between groups concerning Paprosky classification (p = 0.003) and the use of augments (p = 0.01). Missing data concerning Paprosky classification (1 case in PE group) as well as bone grafting (4 cases in DMC group, 5 cases in PE group).

Surgical procedures

The surgical approach was direct lateral in all but 13 cases where the transfemoral approach was chosen. Revision of the stem at index procedure occurred in 63 cases. After removal of the cup component and reaming for the TM shell, morselized bone graft (42 cases) or augments (18 cases) were used when necessary to fill acetabular defects, a TM shell with appropriate dimensions was impacted into the acetabulum, and this was fixed with additional screws whenever necessary (in 114 cases, median 3 (1–9) screws). Cup positioning within the “safe zones” as proposed by Lewinnek et al. (1978) was aimed for. DMCs with an external diameter at least 14 mm smaller than the external diameter of the implanted TM shells were used to ensure sufficient amounts of bone cement (Palacos R + G; Heraeus Kulzer GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) between the DMC and the TM shell, i.e., the minimal external diameter for the TM shells in the DMC group was 58 mm, since the smallest DMC had an external diameter of 44 mm. Postoperatively obtained radiographs confirmed adequate positioning of the components. Patients were allowed full weight-bearing postoperatively, even in cases with transfemoral approaches.

Clinical follow-up

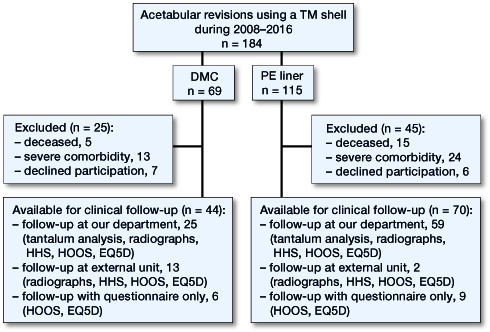

In our department, clinical and radiographic follow-up after acetabular revision surgery is scheduled 3–4 months and 1 year postoperatively. For this study, an additional follow-up visit was offered. Of the 184 patients, 20 were deceased at final follow-up, and 37 patients were excluded from the clinical follow-up due to significant comorbidity, leaving 127 patients eligible for clinical follow-up. 13 patients declined to participate in this study, leaving 114 of 184 patients for clinical follow-up (Figure 1). All patients received the Hip disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (HOOS) and EQ5D via surface mail and were asked to return the forms. 15 patients from outside our county were scheduled for follow-up at the orthopedic department closest to their place of residence. For these patients, an analysis of tantalum ion concentration was not possible.

Figure 1.

Description of the inclusion of the study population.

The HOOS and EQ5D questionnaires were filled in by 114 patients. Hip function was assessed using the Harris Hip Score (HHS) in 99 hips. Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs were taken in 99 hips and analyzed by 2 observers regarding cup abduction and anteversion angles, migration of the implant, screw breakage, osteolysis, or radiolucent lines. Osteolysis, migration exceeding 2 mm, screw breakage, or radiolucent lines >30% of the bone-implant interface were considered radiographic signs of loosening.

Tantalum concentrations were measured in 84 of 184 patients. Whole-blood samples were obtained, the same batch of cannulas and tubes (10-mL polypropylene with sodium heparin) was used, and samples were analyzed by a certified laboratory (ALS Scandinavia AB, Luleå, Sweden) using inductively coupled plasma sector field mass spectrometry (ICP-SFMS) with a tantalum detection threshold of 0.05 µg/L.

Statistics

Continuous data were described as medians with ranges or means with standard deviation (SD). Estimation uncertainty was approximated by 95% confidence intervals (CI). Categorical data were summarized in cross-tables and the chi-square test was used to investigate differences between groups. We calculated cumulative unadjusted component survival using the Kaplan–Meier method, with the endpoints dislocation, or re-revision due to instability, due to aseptic loosening, or for any reason. The Mantel–Haenszel log-rank test estimated statistical difference in survival between groups. We fitted Cox exploratory multivariable regression models to determine hazard ratios (HR) adjusted for the confounders age, sex, and acetabular defect size (assessed by the Paprosky classification). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

All data were analyzed using the R software version 3.3.1 and RStudio version 0.99.993 with the “Gmisc” and “rms” packages (R Core Team 2016).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and was approved by the local ethics committee (Regionala Etikprövningsnämnden Uppsala, entry no. 2014/108, April 16, 2014, and entry no. 2014/108/3, April 19, 2017). The study was in part financed by Zimmer. However, neither Zimmer nor its employees took any part in study design, collecting the data, analysis of the data, or writing of the manuscript.

Results

Dislocation rates

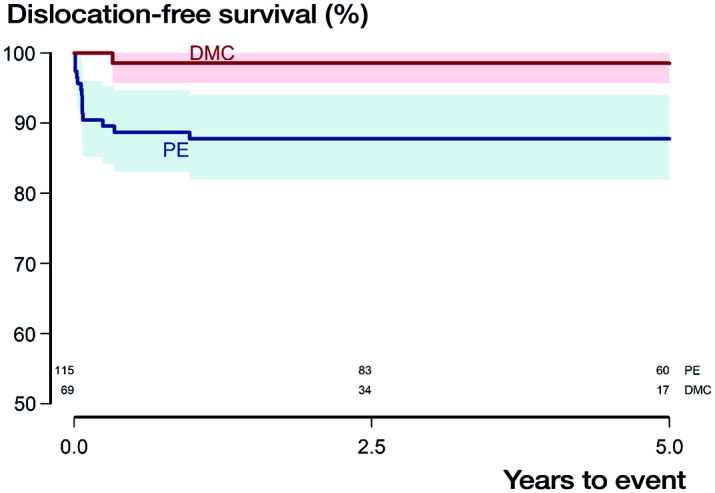

There was 1 dislocation in the DMC group compared with 14 dislocations in the PE group. Of the 14 dislocated hips in the PE group 12 were uncemented snap-fit liners; femoral head size was 28 mm in 9 cases and 32 mm in 5. Head size was not statistically significantly associated with dislocation. 6 of the 14 dislocated hips in the PE group underwent stem revision at index procedure, as did the only dislocated hip in the DMC group. The dislocated hip in the DMC group remained dislocated because the patient’s general health was too poor to proceed with further surgery. 11 of the 14 patients with dislocations in the PE group underwent re-revision due to persistent instability, 1 patient was treated with closed reduction and remained dislocation-free until follow-up, 1 patient was diagnosed with a periprosthetic joint infection, and 1 patient was re-revised due to aseptic loosening that had caused the dislocation. Dislocation-free survival after 4 years was thus 99% (CI 96–100) in the DMC group, whereas it was 88% (CI 82–94, p = 0.01, Figure 2) in the PE group. The adjusted HR for the occurrence of dislocation was 0.11 (CI 0.01–0.8, p = 0.03) for the DMC group.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves with the endpoint dislocation with shaded area indicating CI (p = 0.01, derived from Mantel–Haenszel log-rank test). Numbers at risk for both subgroups are given above the X-axis.

Analysis of postoperative radiographs showed that mean anteversion was 13 (range 0–35) degrees, mean inclination was 46 (range 35–58) degrees, and cranialization of the center of rotation was mean 3 (range –11 to 13) mm in the group of dislocated implants.

Implant survival

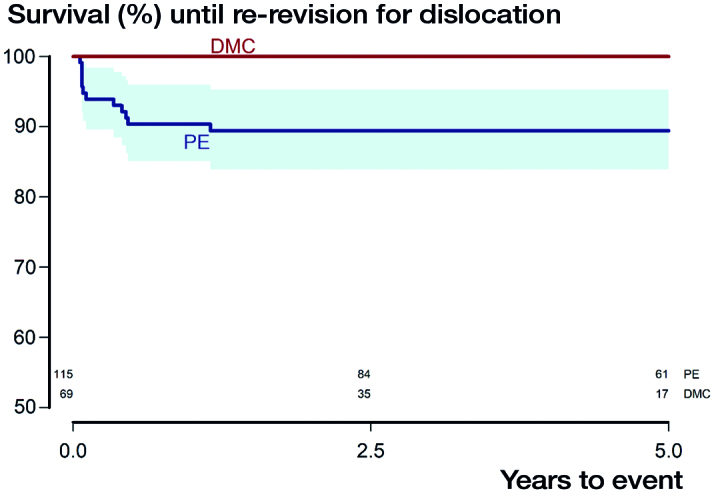

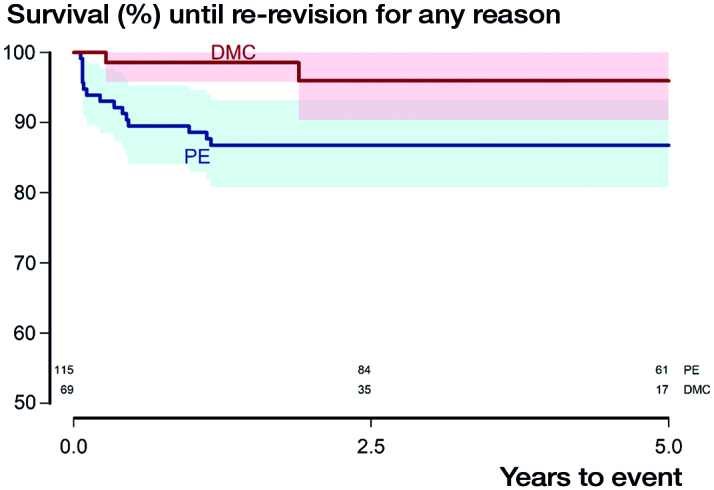

Within the DMC group, 2 re–revisions occurred, both due to aseptic loosening at the interface between the TM shell and bone, not between the DMC and the TM shell. In the PE group, there were altogether 15 re-revisions. Apart from the 13 re-revisions accounted for above, 1 additional hip was re-revised due to aseptic loosening, and 1 was revised due to persistent pain related to a cancellous screw penetrating the inner pelvic cortex into the iliopsoas muscle (Table 2). For the endpoint re-revision due to dislocation we thus obtained 100% survival for the DMC group after 4 years, whereas it was 89% (95% CI 84–95, p = 0.006, Figure 3) in the PE group. With re-revision for any reason as the endpoint, 4-year survival within the DMC group was 96% (CI 90–100), whereas it was 87% (CI 81–93) for the PE group (p = 0.03, Figure 4). With re-revision due to aseptic loosening as the endpoint, the DMC group had a 4-year survival of 96% (CI 90–100), while it was 98% (CI 95–100) for the PE group (p = 0.5).

Table 2.

Description of the re-revised study population

| PE (n = 15) | DMC (n = 2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||

| Male | 6 | 1 |

| Female | 9 | 1 |

| Paprosky: | ||

| I | 2 | 0 |

| IIA | 1 | 0 |

| IIB | 1 | 1 |

| IIC | 8 | 0 |

| IIIA | 2 | 0 |

| IIIB | 1 | 1 |

| Reason for index procedure: | ||

| Loosening | 12 | 2 |

| Dislocation | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 0 |

| Number of revisions: | ||

| First-time revision | 11 | 2 |

| Previously revised | 4 | 0 |

| Bone graft: | ||

| No | 11 | 0 |

| Yes | 3 | 2 |

| Stem revised at index procedure: | ||

| No | 9 | 2 |

| Yes | 6 | 0 |

| Head size: | ||

| 22 | 0 | 1 |

| 28 | 9 | 1 |

| 32 | 4 | 0 |

| Other | 2 | 0 |

| Reason for re-revision: | ||

| Aseptic loosening | 2 | 2 |

| Dislocation | 11 | 0 |

| Pain | 1 | 0 |

| Infection | 1 | 0 |

Note: There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups. Missing data for 1 patient in the PE group concerning bone grafting.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves with the endpoint re-revision for instability with shaded area indicating CI (p = 0.006, derived from Mantel–Haenszel log-rank test). Numbers at risk for both subgroups are given above the X-axis.

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves with the endpoint re-revision for any reason with shaded area indicating CI (p = 0.03, derived from Mantel–Haenszel log-rank test). Numbers at risk for both subgroups are given above the X-axis.

Clinical follow-up

The mean tantalum concentrations were 0.1 µl/L (CI 0.05–0.2) in the DMC group and 0.1 µg/L (CI 0.05–0.2) in the PE group, with 3 of 25 patients below detection limit in the DMC group, and 5 of 59 patients below detection limit in the PE group. The maximal tantalum concentration of 0.5 µg/L was measured in a patient in the PE group; the maximal concentration in the DMC group was 0.3µg/L.

After a mean of 4.9 (range 0.5–8.9) years, none of the hips that underwent radiographic examination showed signs of migration above the predefined threshold, osteolysis, breakage of screws, or radiolucent lines exceeding 30% of the cup circumference. Overall, hip function was satisfactory, with a mean HHS of 77 (25–100). In the HOOS subdimensions there were only small differences between the 2 groups that were neither statistically nor clinically significant. There were small and statistically not significant differences between groups in global health, as assessed by EQ5D (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

EQ5D subdimensions

| EQ5D | PE (n = 69) | DMC (n = 44) |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility: | ||

| No problems | 11 | 17 |

| Some problems | 44 | 23 |

| Extreme problems | 13 | 4 |

| Anxiety/depression: | ||

| No problems | 16 | 23 |

| Some problems | 20 | 13 |

| Extreme problems | 33 | 8 |

| Usual activities: | ||

| No problems | 14 | 25 |

| Some problems | 22 | 11 |

| Extreme problems | 32 | 8 |

| Pain/discomfort: | ||

| No problems | 10 | 13 |

| Some problems | 39 | 24 |

| Extreme problems | 20 | 7 |

| Self-care: | ||

| No problems | 16 | 33 |

| Some problems | 12 | 4 |

| Extreme problems | 41 | 7 |

Note: 1 patient in the PE group did not answer all questions.

Table 4.

HOOS subdimensions

| HOOS | group | n | mean | SD | range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain: | PE | 70 | 70 | 28 | 0–100 |

| DMC | 43 | 73 | 25 | 5–100 | |

| Symptoms: | PE | 70 | 68 | 25 | 10–100 |

| DMC | 44 | 71 | 27 | 10–100 | |

| ADL: | PE | 70 | 67 | 28 | 0–100 |

| DMC | 44 | 69 | 27 | 12–100 | |

| Sport/recreation: | PE | 70 | 44 | 33 | 0–100 |

| DMC | 44 | 45 | 30 | 0–100 | |

| QOL: | PE | 70 | 52 | 30 | 0–100 |

| DMC | 44 | 58 | 30 | 0–100 |

Note: 1 patient did not answer all questions. No statistically significant difference was found.

Discussion

Recurrent dislocation after hip revision surgery is a frequent and devastating complication; thus technical concepts that reduce joint instability after acetabular revision surgery are warranted. In our present study, no re-revision was performed due to instability after the use of a DMC in conjunction with a TM shell, indicating that cementing DMCs into TM shells may be an adequate way to address joint instability after hip revision surgery. It is noteworthy that there is a selection bias to the disadvantage of the DMC group, since the combination of a DMC inside a TM shell was chosen when the risk of instability was considered higher than average, and because the combination of a DMC with a TM shell was more often used in more severe acetabular defects.

It should be kept in mind that the majority of hips within the PE group that dislocated had received uncemented snap-fit liners. Smaller head size seemed not to be associated with an increased risk of dislocation, and we found no obvious malpositioning of the cup in the cases that suffered from dislocation. It has been argued that procedures involving isolated cup revision are associated with a higher risk of dislocation than procedures where cup and stem revision are combined (Mohaddes et al. 2013), but in our material this could not be confirmed.

The risk of dislocation is substantial after hip revision surgery—also after the use of TM shells. Several studies have shown that recurrent dislocation is an issue after the use of TM shells (Unger et al. 2005, Lakstein et al. 2009, Kremers et al. 2012). Most notably, the authors of a study on 827 patients with TM revision shells (Skyttä et al. 2011) concluded that “the most common reason for revision was dislocation of the prosthesis with or without malposition of the socket (60%)”.

In our study, dislocation was the main reason for re-revision when using PE liners in conjunction with TM shells. However, when patients within the PE group were re-revised with a DMC due to recurrent dislocations (7 patients), no further dislocations occurred. Of the 4 remaining patients that underwent re-revision due to instability but did not receive a DMC, 1 patient remained unstable. Cementing a DMC into a TM shell could thus also be considered suitable in cases of recurrent dislocations after acetabular revision surgery.

Despite corrosion, metallosis, and adverse tissue reactions to metal implants being hotly debated, we were unable to find systematic studies on tantalum ion release after the use of TM shells. We therefore determined serum concentrations of tantalum in 84 patients as a measure of tantalum release, and found a 10-fold increase compared with the reference value of 0.008–0.010 µg/L obtained in a healthy population without any implants, but about a 100-fold lower mean concentration than in the cited case report (Babis et al. 2014). It should be kept in mind that our measurements are derived from patients with radiographically stable constructs, and the extensive increase in tantalum concentrations observed after a failed revision THA was not expected in our patients. Tantalum concentrations were not statistically significantly higher in patients who had received a DMC cemented into a TM shell when compared with those who had PE liners. Whether the elevated tantalum concentrations observed in both groups we investigated are of clinical importance is an open question, and no reference group with hip implants made of materials other than tantalum was available.

Our results indicate a satisfactory clinical outcome in terms of patient-reported outcome measures (PROM), and they are similar to those described by other authors (Flecher et al. 2008, Batuyong et al. 2014, Konan et al. 2016). PROM were slightly better in the DMC group, but the observed differences compared with the PE group were small. The minimal clinically important difference for the scores reported here is higher than the estimated difference between our 2 groups, indicating that these findings lack clinical relevance (Berliner et al. 2016, Singh et al. 2016).

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

There are several limitations to this study. Since it is a retrospective cohort study we faced the common problems of missing data, underreporting, relatively large loss to clinical follow-up, and possible confounders that we cannot control for. Whether the actual acetabular defects are correctly represented by the radiographic assessment that was based on Paprosky’s classification is unknown because operative notes were not detailed enough on this topic. PROM and functional outcome scores were only established at clinical follow-up but not at baseline, and we are therefore unable to conclude whether the chosen treatment improved our patients’ quality of life. Mean follow-up was shorter for the DMC group than for the PE group because the technique of cementing a DMC into a TM shell gradually replaced the previously common use of PE liners. Due to the stepwise introduction of different implants and due to different sizes of acetabular defects the Continuum, the TM Modular, and the Trilogy TM cup as well as the TM revision shell are included in this study. However, we investigated porous tantalum as a method of fixation—rather than a specific cup design. The 2 investigated groups are not equal with respect to the severity of acetabular defects, and surgeons may have chosen a DMC in cases considered “more difficult” for other reasons than acetabular defect size, introducing residual confounding.

We fitted exploratory multivariable regression models to estimate the adjusted risk of dislocation or re-revision for various reasons, but the scarcity of events inflated confidence intervals and estimation uncertainty was therefore large. Instability causing re-revision generally precludes re-revision due to aseptic loosening as an endpoint, which implies that the risk of re-revisions due to aseptic loosening in the PE group could be higher than our estimate.

There are, however, certain strengths to this study. Our cohort of 184 patients with information on Paprosky classification is relatively large. Our analysis of all patients’ charts—even charts kept at external units—enabled us to draw conclusions not only regarding the endpoint re-revision due to instability, but also regarding the endpoint dislocation. We also have reliable data concerning demographics, re-revisions, and deaths. Furthermore, clinical follow-up was available for 114 hips, a rather large cohort as regards acetabular revision surgery. Our evaluation of tantalum concentrations in 84 patients is the first of its kind. This study is also the first systematic analysis of TM shells combined with DMCs, comparing a new technique with the previously recommended procedure based on the use of standard PE liners.

Conclusion

We believe that the technique of cementing a DMC into a TM shell is a valuable treatment option in acetabular revision surgery, especially for patients that are at higher risk of dislocation. The new technique seems to be safe since we found no increased risk of implant loosening, and no increased liberation of tantalum ions.

All authors were involved in writing the manuscript. AB collected data under the guidance of HM. AB and NPH analyzed the radiographs. AB and NPH performed the statistical analysis.

We would like to thank Elin Kramer for her efforts during follow-up and analysis of radiographs. Special thanks to our department colleagues associate professor Jan Milbrink and professor Olle Nilsson for introducing this new treatment strategy.

Acta thanks Martin Clauss and Marc Nijhof for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Babis G C, Stavropoulos N A, Sasalos G, Ochsenkuehn–Petropoulou M, Megas P.. Metallosis and elevated serum levels of tantalum following failed revision hip arthroplasty: A case report. Acta Orthop 2014; 85 (6): 677–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batuyong E D, Brock H S, Thiruvengadam N, Maloney W J, Goodman S B, Huddleston J I.. Outcome of porous tantalum acetabular components for Paprosky type 3 and 4 acetabular defects. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (6): 1318–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann N A, Weiss S, Klotz M C, Gondan M, Jaeger S, Bitsch R G.. Loosening after acetabular revision: Comparison of trabecular metal and reinforcement rings. A systematic review. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29 (1): 229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner J L, Brodke D J, Chan V, SooHoo N F, Bozic K. J. John Charnley Award: Preoperative patient-reported outcome measures predict clinically meaningful improvement in function after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016; 474 (2): 321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland W S, Bhattacharya R, Holland J P, Brewster N T.. Use of porous trabecular metal augments with impaction bone grafting in management of acetabular bone loss. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(4): 347–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann A, Fredlund E, Mallmin H, Hailer N P.. Are porous tantalum cups superior to conventional reinforcement rings? Acta Orthop 2017; 88 (1): 35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flecher X, Sporer S, Paprosky W.. Management of severe bone loss in acetabular revision using a trabecular metal shell. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(7): 949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A I, Bartolone P, Lubbeke A, Dupuis Lozeron E, Peter R, Hoffmeyer P, Christofilopoulos P.. Comparison of dual-mobility cup and unipolar cup for prevention of dislocation after revision total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2017; 88 (1): 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailer N P, Weiss R J, Stark A, Karrholm J.. Dual-mobility cups for revision due to instability are associated with a low rate of re-revisions due to dislocation: 228 patients from the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (6): 566–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konan S, Duncan CP, Masri B A, Garbuz D S.. Porous tantalum uncemented acetabular components in revision total hip arthroplasty: A minimum ten-year clinical, radiological and quality of life outcome study. Bone Joint J 2016; 98-B (6): 767–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremers H M, Howard J L, Loechler Y, Schleck C D, Harmsen W S, Berry D J, Cabanela M E, Hanssen A D, Pagnano M W, Trousdale R T, Lewallen D G.. Comparative long-term survivorship of uncemented acetabular components in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (12): e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakstein D, Backstein D, Safir O, Kosashvili Y, Gross A E.. Trabecular metal cups for acetabular defects with 50% or less host bone contact. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467 (9): 2318–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinnek G E, Lewis J L, Tarr R, Compere C L, Zimmerman J R.. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978; 60(2): 217–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohaddes M, Garellick G, Karrholm J.. Method of fixation does not influence the overall risk of rerevision in first-time cup revisions. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (12): 3922–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohaddes M, Rolfson O, Karrholm J.. Short-term survival of the trabecular metal cup is similar to that of standard cups used in acetabular revision surgery. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (1): 26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn D, Freeman M A, Hill P F, Evans S J.. The measurement of migration of the acetabular component of hip prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1989; 71 (4): 629–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paprosky W G, Perona P G, Lawrence J M.. Acetabular defect classification and surgical reconstruction in revision arthroplasty: A 6-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty 1994; 9 (1): 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2016. http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Kärrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Mäkelä K, Espehaug B, Pedersen A B, Mehnert F, Furnes O.. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data, II: Guidelines. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodushkin I, Engstrom E, Stenberg A, Baxter D C.. Determination of low-abundance elements at ultra-trace levels in urine and serum by inductively coupled plasma-sector field mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem 2004; 380(2): 247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J A, Schleck C, Harmsen S, Lewallen D.. Clinically important improvement thresholds for Harris Hip Score and its ability to predict revision risk after primary total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2016; 17: 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skyttä E T, Eskelinen A, Paavolainen P O, Remes V M.. Early results of 827 trabecular metal revision shells in acetabular revision. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (3): 342–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer B D, Fehring T K, Griffin W L, Odum S M, Masonis J L.. Why revision total hip arthroplasty fails. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467 (1): 166–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2016, https://registercentrum.blob.core.windows.net/shpr/r/-rsrapport-2016-SJirXXUsb.pdf“.

- Unger A S, Lewis R J, Gruen T.. Evaluation of a porous tantalum uncemented acetabular cup in revision total hip arthroplasty: Clinical and radiological results of 60 hips. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20 (8): 1002–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]