Abstract

Background and purpose

Osteoarthritis (OA) imposes a substantial burden on individuals and societies. We report on the burden of knee and hip OA in the Nordic region.

Patients and methods

We used the findings from the 2015 Global Burden of Diseases Study to explore prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) of OA in the 6 Nordic countries during 1990–2015 (population of about 27 million in 2015).

Results

During 1990–2015, the number of prevalent OA cases increased by 43% to 1,507,587 (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 1,454,338–1,564,778) in the region. OA accounted for 1.3% (UI 1.0–1.7) of YLDs in 1990, increasing to 1.6% (UI 1.2–2.0) in 2015. Of 315 causes studied, OA was the 15th leading cause of YLDs, causing 52,661 (UI 34,056–77,499) YLDs in 2015; of these 23% were attributable to high body mass index. The highest relative importance of OA was reported for women aged 65–74 years (8th leading cause of YLDs in 2015). Among the top 30 leading causes of YLDs in the region, OA had the 5th greatest relative increase in total YLDs during 1990–2015. From 1990 to 2015, increase in age-standardized YLDs from OA in the region was slightly lower than increase at the global level (7.5% vs. 10.5%). OA was, however, responsible for a higher proportional burden of DALYs in the region compared with the global level.

Interpretation

The OA burden is high and rising in the Nordic region. With population growth, aging, and the obesity epidemic, a substantial rise in the burden of OA is expected and should be addressed in health policies.

Painful osteoarthritis (OA) of the peripheral joints is often associated with physical disability and deterioration in health-related quality of life, translating into a substantial burden on individuals and societies (Hiligsmann and Reginster 2013, Cross et al. 2014, Kiadaliri et al. 2016). Although OA may affect all joints, the knee, hip, and hand are most commonly affected. OA incidence and prevalence has increased over recent decades and this is generally attributed to aging of the population and rising prevalence of obesity (Nguyen et al. 2011, Neogi and Zhang 2013, Rahman et al. 2014, Yu et al. 2015). In addition, occurrence of OA among younger active people has been reported to be increasing (Leskinen et al. 2012, Yu 2015).

The rising incidence and prevalence of OA implies that its burden will increase and impose significant pressure on healthcare systems worldwide. An up-to-date and accurate estimate of the burden of OA and its burden in relation to other diseases can aid informed decision-making by health authorities. In addition, monitoring and comparison of the country-specific burden would provide useful insights to assess health systems’ performance and benchmark a country against others. However, to do so, consistent and comparable data across diseases and geographies over times are required. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study (Murray and Lopez 1996) aims to respond to this requirement by estimating comprehensive and internally consistent estimates of mortality and disability from major diseases, injuries, and risk factors. In the latest iteration of the GBD study, GBD 2015, the burden of 315 causes including OA has been estimated for 195 countries during 1990–2015 (GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators 2016, GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2016, GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). The GBD 2015 reported the estimates for the Nordic region as a whole. In the current study, we aimed to explore, for the first time, prevalence and disability due to OA in the Nordic region and across countries in the region between 1990 and 2015 using the findings from the GBD 2015.

Methods

The GBD 2015 estimated the burden of 315 causes of diseases and injuries and 79 risk factors for 195 countries, 7 super-regions, and 21 regions. The GBD uses 3 metrics to quantify the burden of a disease: years of life lost (YLLs) due to premature death, years lived with disability (YLDs) for the non-fatal health loss, and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) as a measure of total burden (fatal and non-fatal). YLLs are calculated by multiplying the number of deaths from a cause in each age group by the reference life expectancy at the average age of death for those who die in that age group (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016). YLDs for each age, sex, location, and calendar year are computed by multiplying prevalence of a given cause sequela by disability weights for that sequela (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2016). DALYs are calculated as the sum of YLLs and YLDs. 1 DALY is equivalent to 1 healthy year of life lost due to a specific disease or injury.

In the GBD 2015, the OA reference case definition was symptomatic OA of the hip or knee radiologically confirmed as Kellgre–Lawrence grade 2–4 (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2016). OA was assumed to be non-fatal and no mortality and no YLLs were estimated. For non-fatal health loss, the GBD 2013 systematic reviews of epidemiological measures for OA were updated in 2014. A list of all data points used in GBD 2015 is available from IHME Global Health Data Exchange (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2015/data-input-sources).

Statistics

The detailed information on data and statistical analysis of the GBD 2015 study are available in the web appendix of a previous publication (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2016, http://www.thelancet.com/cms/attachment/2090344431/2075672336/mmc1.pdf). In short, the data from systematic reviews were assembled using DisMod-MR 2.1, a Bayesian meta-regression tool to estimate prevalence by location, age, sex, and year accounting for study level and predictive covariates. The sequence of estimation in DisMod-MR 2.1 occurs at 5 levels (called “cascade”): global, super-region, region, country and, where applicable, subnational geographical unit. An initial run is made with all data points for all locations, age, sex, and time periods to get an initial fit at the global level. The estimates from the global fit with adjustments for fixed effects (adjusting for study characteristics and predictive covariates) and random effects by geography is passed on to each of 7 super-region fits by sex and year (1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015) as priors and confronted with data from the super-region, sex, and year to make an initial fit for each super-region. For OA, the data from studies that reported OA based on radiographic only, self-reported OA with pain, reporting a physician diagnosis of OA, and symptomatic OA without radiographic confirmation were included and adjusted as study-level covariates in the modelling. The mean body mass index (BMI) was included as a predictive covariate. Then estimates from the super-region are passed on similarly to 21 region fits by sex and year and in turn the region estimates determine the priors for country estimates, and the country estimates determine the prior being passed down to subnational locations, where applicable. This cascade allows the GBD estimates to be made for locations with sparse or no primary data. In addition, disease-by-disease value priors may be set. In the case of OA, a prior value of no incidence and prevalence before the age of 30, zero remission, and no excess mortality were assumed. Based on the severity of OA, 3 sequelae (mild, moderate, and severe OA) were considered. Severity was classified according to the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) and the lay description of these was used to elicit disability weights. A random effects meta-analysis model based on the data from 4 studies from 3 regions was used to determine the proportion of people within each of the OA severity levels (based on frequentist methods). All measures were age-standardized using the GBD world population age standard.

For each measure, 95% uncertainty intervals (UI) were calculated by taking the 2.5 and 97.5 centile values of 1,000 draws of the posterior distribution of that measure. It should be noted that as YLLs for OA was assumed to be zero, the YLDs is equal to DALYs.

We obtained the estimates of the GBD 2015 on the burden of OA for the Nordic region and the 6 countries in the region (Denmark, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) for 1990–2015 at 5-year increments (1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015) from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation interactive visualization tools (http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare). The region had a population of around 23 million in 1990 and 27 million in 2015. We reported the burden of OA attributable to high BMI (≥ 22.5) (GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016). We also compared the observed YLDs of OA with those expected based on the socio-demographic index (SDI). The SDI was constructed in the GBD 2015 for each location-year as a measure of overall development. It is based on the geometric mean of income per capita, average years of schooling among people aged 15 years or older, and total fertility rate (GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators 2016). In the Nordic region in 2015 the SDI values were as follow: 0.76 for Greenland, 0.89 for Sweden, 0.89 for Finland, 0.91 for Denmark, and 0.94 for Norway. We also decomposed the changes in total YLDs from OA between 1990 and 2015 into population growth, aging, and change in age- and sex-specific YLD rates of OA.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Ethics approval not applicable; data are publicly available. We would like to acknowledge support from the Swedish Research Council, Crafoord Foundation, Greta and Kocks Foundation, Österlunds Foundation, the Faculty of Medicine Lund University, Governmental Funding of Clinical Research within National Health Service (ALF) and Region Skåne. No conflicts of interest declared.

Results

Prevalence

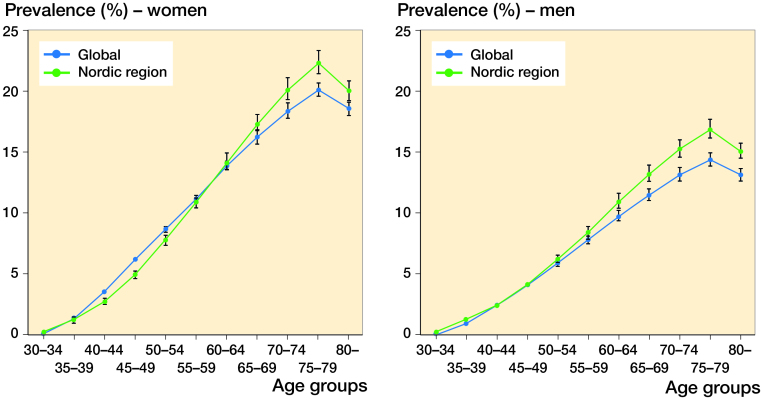

The number of prevalent OA cases increased from 1,051,897 (UI 1,017,093–1,089,896) in 1990 to 1,507,587 (UI 1,454,338–1,564,778) in 2015 in the Nordic region (an increase of 43% [UI 41–45]). The age-standardized prevalence of OA for women in the region was comparable to the global level, even though it was estimated to be higher in Denmark, Greenland, and Iceland and lower in Sweden compared with the global level (Table 1). Among men, the age-standardized prevalence of OA in all Nordic countries but Sweden was higher than the global average. Between 1990 and 2015, the age-standardized prevalence of OA increased by 7.5% (UI 6.1–8.9) in the region, which was slightly higher than the observed increase at the global level. In both sexes, the highest prevalence was observed in people 75–79 years old (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Age-standardized prevalence (%) of osteoarthritis in the countries of the Nordic region and the world

| Women |

Percent change | Men |

Percent change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 1990 | 2015 | 1990–2015 | 1990 | 2015 | 1990–2015 |

| Global | 3.8 (3.7–3.9) | 4.1 (3.9–4.2) | 6.6 (5.6–7.6) | 2.6 (2.6–2.7) | 2.8 (2.8–2.9) | 7.6 (6.5–8.5) |

| Nordic region | 3.7 (3.6–3.9) | 4.0 (3.9–4.2) | 8.4 (6.6–10.2) | 2.9 (2.8–3.1) | 3.2 (3.1–3.3) | 8.1 (6.3–9.8) |

| Denmark | 4.3 (4.1–4.5) | 4.6 (4.4–4.8) | 7.2 (3.8–10.9) | 3.5 (3.3–3.6) | 3.7 (3.6–3.9) | 8.1 (4.6–11.8) |

| Finland | 3.9 (3.7–4.0) | 4.1 (3.9–4.2) | 4.8 (1.0–8.7) | 3.0 (2.9–3.1) | 3.2 (3.1–3.3) | 6.4 (2.7–10.3) |

| Greenland | 4.4 (4.2–4.6) | 4.8 (4.6–5.0) | 8.1 (4.7–12.0) | 3.6 (3.4–3.7) | 3.9 (3.7–4.0) | 7.9 (4.5–11.2) |

| Iceland | 4.1 (3.9–4.3) | 4.4 (4.2–4.7) | 8.2 (3.9–13.0) | 3.2 (3.1–3.4) | 3.5 (3.3–3.7) | 9.1 (4.9–13.6) |

| Norway | 3.6 (3.5–3.8) | 3.9 (3.7–4.1) | 7.4 (3.4–11.8) | 2.9 (2.8–3.1) | 3.2 (3.0–3.3) | 8.0 (3.8–11.7) |

| Sweden | 3.4 (3.2–3.5) | 3.8 (3.6–3.9) | 11.9 (8.3–15.8) | 2.6 (2.5–2.7) | 2.8 (2.7–3.0) | 8.7 (5.1–11.9) |

Values in parentheses show 95% uncertainty interval.

Figure 1.

Age- and sex-specific prevalence (%) of osteoarthritis in the Nordic region and the world, 2015.

YLDs

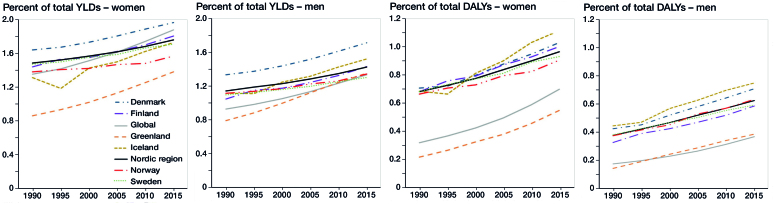

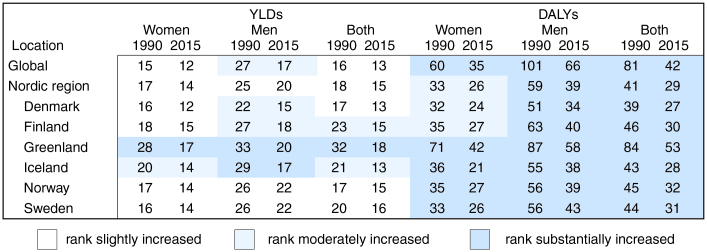

Between 1990 and 2015, total YLDs of OA increased by 38% (UI 35–40) to 30,974 (UI 19,987–45,631) in women; and by 53% (UI 49–55) to 21,687 (UI 14,064–32,040) in men in the Nordic region. In both sexes, the increases in total YLDs from 1990–2015 in the region were smaller than the global rate of increase (Figure S1, Supplementary data). In the Nordic region, OA contributed to 1.33% (UI 1.00–1.67) of total YLDs in 1990 and this increased to 1.61% (UI 1.22–2.01) in 2015 (ranging from 1.37% [UI 1.03 to 1.72] in Greenland to 1.85% [UI 1.40–2.31] in Denmark, Figure 2). Of 315 causes studied, OA was ranked as the 15th leading cause of total YLDs in the region in 2015 (Figure 3). In addition, OA was among 10 leading causes of YLDs in those aged 55–74 years in 2015 (Figure S2, Supplementary data). While overall OA had a higher relative importance in women (14th leading cause of YLDs) than men (20th leading cause of YLDs), in those aged 30–50 years the opposite was observed. Among the top 30 leading causes of YLDs in the region, OA had the 5th greatest relative increase in total YLDs between 1990 and 2015 (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Burden of osteoarthritis as a proportion of total years lived with disability (YLDs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) 1990–2015, by sex and location.

Figure 3.

The rank of osteoarthritis among 315 causes in terms of total years lived with disability (YLDs) and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 1990 and 2015, by sex and location (lower number indicates higher relative importance).

Table 2.

The burden of OA in comparison with 30 leading causes of years lived with disability (YLDs) for both sexes combined in the Nordic region in 2015

| Percent change1990–2015 in |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | crude | age-standardized | |||

| Rank | Cause | Total YLDs (95% UI), 2015 | YLDs | YLD rates | YLD rates |

| 1 | Low back pain | 341,720 (243,165–471,373) | 16.5 | 1.6 | –2.4 |

| 2 | Neck pain | 257,221 (173,423–347,621) | 24.1 | 8.3 | 1.5 |

| 3 | Major depressive disorder | 171,717 (115,456–234,977) | 11.5 | –2.7 | –3.0 |

| 4 | Age-related and other hearing loss | 148,248 (101,265–208,190) | 37.0 | 19.6 | 4.4 |

| 5 | Diabetes mellitus | 138,677 (95,904–190,884) | 56.1 | 36.2 | 19.6 |

| 6 | Migraine | 132,779 (81,995–196,494) | 11.6 | –2.6 | –0.2 |

| 7 | Anxiety disorders | 114,250 (78,464–154,855) | 11.8 | –2.4 | –1.1 |

| 8 | Other musculoskeletal disorders | 104,139 (69,148–144,842) | 40.4 | 22.5 | 12.9 |

| 9 | Falls | 92,541 (63,146–129,745) | –3.5 | –15.8 | –25.9 |

| 10 | Iron-deficiency anemia | 82,713 (55,250–120,348) | 24.2 | 8.4 | 13.1 |

| 11 | Asthma | 73,429 (47,637–102,761) | –7.6 | –19.4 | –18.1 |

| 12 | Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias | 66,549 (47,170–88,334) | 39.6 | 21.8 | 0.9 |

| 13 | Edentulism and severe tooth loss | 61,886 (41,423–86,253) | 30.8 | 14.2 | 0.5 |

| 14 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 55,530 (46,435–65,762) | 25.0 | 9.1 | –3.9 |

| 15 | Osteoarthritis | 52,661 (34,056–77,499) | 43.3 | 25.1 | 7.5 |

| 16 | Schizophrenia | 46,913 (34,275–58,739) | 17.4 | 2.5 | –0.8 |

| 17 | Dysthymia | 42,564 (28,457–61,162) | 18.2 | 3.1 | –0.3 |

| 18 | Bipolar disorder | 39,793 (24,723–58,761) | 12.2 | –2.1 | 0.9 |

| 19 | Dermatitis | 39,510 (27,057–54,714) | 12.5 | –1.9 | 0.0 |

| 20 | Other mental and substance use disorders | 38,861 (27,055–52,365) | 17.0 | 2.1 | 0.6 |

| 21 | Alcohol use disorders | 38,585 (25,998–54,459) | 3.1 | –10.1 | –10.5 |

| 22 | Medication overuse headache | 38,539 (25,260–54,435) | 16.3 | 1.5 | –1.7 |

| 23 | Benign prostatic hyperplasia | 37,653 (24,423–53,434) | 45.6 | 27.0 | 6.9 |

| 24 | Rheumatoid arthritis | 37,311 (26,047–49,975) | 15.6 | 0.9 | –9.9 |

| 25 | Psoriasis | 36,829 (25,740–49,858) | 20.2 | 4.9 | 1.2 |

| 26 | Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 36,593 (24,776–49,774) | 62.5 | 41.8 | 21.4 |

| 27 | Other sense organ diseases | 35,211 (22,070–51,023) | 29.0 | 12.5 | 2.2 |

| 28 | Ischemic heart disease | 31,912 (21,923–43,427) | –1.7 | –14.2 | –26.5 |

| 29 | Other unintentional injuries | 30,357 (19,917–43,616) | –33.4 | –41.9 | –48.2 |

| 30 | Other congenital birth defects | 29,647 (12,960–72,466) | 99.0 | 73.6 | 77.2 |

UI = uncertainty interval.

In both sexes, the highest and lowest age-standardized YLD rates of OA were seen in Greenland and Sweden, respectively (Figure S3, Supplementary data). The ratio of age-standardized YLDs rate in the Nordic region to the global level was 0.65 in women and 0.73 in men. Between 1990 and 2015, the age-standardized YLDs rate of OA rose by 7.5% (UI 6.0–9.1) in the region, statistically significantly lower than the observed increase at the global level (10.5%, UI 9.1–12.0, Figure S1, Supplementary data). Across the Nordic countries, the largest and smallest increases in age-standardized YLD rates of OA were reported for women in Sweden and Finland, respectively. In 2015, the women-to-men age-standardized YLDs rate ratio was 1.27 in the region (ranging from 1.22 in Denmark to 1.32 in Sweden), which was slightly lower than the global level (1.43).

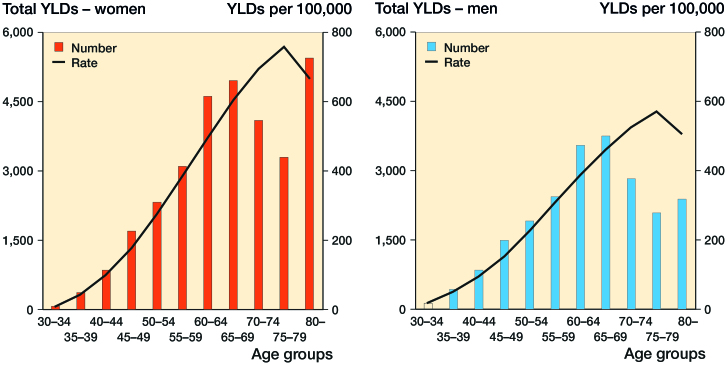

Among women, the observed age-standardized YLD rates of OA were lower than expected on the basis of SDI alone in all Nordic countries, but among men this was the case only in Finland, Greenland, and Sweden in 2015 (Figure S4, Supplementary data). While the highest YLD rates were observed for people aged 75–79 years in both sexes, those women aged 80+ years and men aged 65–69 years had the highest number of YLDs (Figure 4). YLD rates were higher in women compared with men in all age groups except those aged 30–39 years. In the Nordic region in 2015, 23.7% and 22.4% of total YLDs of OA were attributable to high BMI in women and men, respectively, higher than the global average (Figure S5, Supplementary data). The decomposition analysis suggested that in all Nordic countries but Sweden and Norway, population aging made the highest contribution to the rise in total YLDs from 1990 to 2015 (Table 3, Supplementary data).

Figure 4.

Total and age-specific rates of years lived with disability (YLDs) from osteoarthritis in the Nordic region in 2015, by sex and age groups.

DALYs

Between 1990 and 2015, the burden of OA as a proportion of total DALYs increased from 0.69% (UI 0.49–0.93) to 0.97% (UI 0.70–1.30) in women and from 0.38% (UI 0.26–0.52) to 0.63% (UI 0.45–0.85) in men in the Nordic region (Figure 2). While globally OA was ranked as 35th (66th) leading cause of total DALYs in women (men) in 2015, it had a higher relative importance in the region (ranked as 26th and 39th leading cause of total DALYs in women and men, respectively (Figure 3).

Discussion

This report is, to our knowledge, the first comparative investigation of the OA burden in the Nordic region. The burden of OA consistently rose in the region from 1990 through 2015, mainly due to population aging. The burden peaked in the 75–79 age group and was higher in women than in men. In addition, OA was among the 10 leading causes of YLDs in those aged 55–74 years in 2015. While the prevalence of OA in the region was comparable to the global level, the age-standardized estimate of OA burden was lower than the global average. Moreover, the region experienced slightly lower increases in OA burden than the global average between 1990 and 2015. On the other hand, while OA was globally ranked as 42nd leading cause of DALYs, it had higher relative importance in the Nordic region (29th leading cause). Across the countries in the region, Greenland had the highest age-standardized OA burden and the highest proportion of OA burden from total YLDs was seen in Denmark.

There were persistent increases in prevalence and burden of OA across all Nordic countries from 1990 through 2015. The aging population alongside the limited effect of treatments for OA are possible explanations for this increasing trend. Furthermore, marked increases in overweight and obesity in the region (Asgeirsdottir and Gerdtham 2016) could explain part of the rise in OA burden. However, as a recent study noted (Wallace et al. 2017), increases in longevity and obesity cannot fully explain recent increases in OA burden and recent environmental changes (e.g., physical inactivity and high intake of refined carbohydrates) might have played an important role. Moreover, the role of advances in diagnosis and medicalization should not be ruled out as more people are recognizing OA as a treatable condition, not just a given for getting old. The expected future increases in life expectancy and prevalence of overweight and obesity imply that the OA burden will continue to rise in the coming decades. A recent study reported rises in incidence of knee arthroplasty across Nordic countries between 1997 and 2012 (Niemelainen et al. 2017). Moreover, the rate of hospital admissions due to knee and hip OA increased by 50% and 32% between 1998 and 2015 in Sweden (http://www.socialstyrelsen.se). Furthermore, healthcare consultation for OA and primary knee arthroplasty are projected to rise in coming decades in Sweden (Turkiewicz et al. 2014, Nemes et al. 2015). These rising trends highlight the need to incorporate prevention and treatment of OA and sports-related injuries as a priority in health policies in the region. At the population level, raising public awareness about the importance of a healthy lifestyle (e.g., maintain physical fitness and an ideal weight, follow a balanced diet), improving occupational safety and ergonomics, and promoting public awareness of OA should be part of any preventive initiative (Mody and Brooks 2012, Woolf et al. 2012, Bruyere et al. 2014, Briggs et al. 2016, Moradi-Lakeh et al. 2017). At patient level, informing patients about the nature of the disease and treatment goals and importance of self-management, providing lifestyle recommendations (exercise and weight loss), and implementation of integrated models of patient-centered multidisciplinary care have been suggested in order to address the rising burden of OA (Mody and Brooks 2012, Woolf et al. 2012, Bruyere et al. 2014, Briggs et al. 2016). Along these lines, OA prevention and management programs aiming to offer adequate information and exercise to people with knee or hip OA have been initiated in Sweden (Better management of patients with OsteoArthritis, https://boa.registercentrum.se/), Denmark (Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark, https://www.glaid.dk/) and Norway (ActiveOA—Active living with osteoarthritis, http://aktivmedartrose.no/) and establishing similar programs in other Nordic countries is highly recommended.

The magnitude and trend of OA burden varied by sex and country. Incidence, prevalence, and severity of OA is higher in women compared with men (Srikanth et al. 2005, Neogi and Zhang 2013), and any preventive and therapeutic intervention should consider this sex difference. In addition, while the changes in age-standardized YLD rates of OA were comparable between sexes, men observed greater increases in total YLDs than women did over the observation period. This might be partly due to a higher gain in life expectancy in men compared with women over the study period in the Nordic region (life expectancy at birth increased by 6.0 years in men and 4.2 years in women from 1990 through 2015 (GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators 2016)). Differences in population genetic predisposition and lifestyle, in epidemiologic and clinical profile of OA, in prevalence of OA risk factors, and in the healthcare system might partially explain variation in OA burden across the Nordic countries (Croft 1996, Petersson and Jacobsson 2002). Further investigations are required to explore the observed variations in the magnitude and secular trends of OA burden in the region.

In addition to the general limitations of the GBD 2015, which have been acknowledged (GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators 2016, GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2016, GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators 2016), several OA-specific limitations should be mentioned. The reference case definition based on Kellgren–Lawrence grades 2–4 is a conservative definition of OA (Cross et al. 2014) excluding a substantial part of early-stage OA patients from the estimates. The distribution of people across the OA severity levels was determined mainly using the data from high-income regions with no adjustment for potential changes over time. In addition, the brief lay descriptions used to elicit disability weights were mainly focused on major functional consequences and symptoms that could not fully capture the impact of OA on other aspects of health and well-being. The burden of OA was limited to knee and hip OA and other sites were not included. All these limitations likely led to underestimation of the true OA burden in this study. Nevertheless, these results provide an up-to-date comparative assessment of OA burden in the Nordic region of importance to policy-makers and health professionals.

Summary

The burden of OA is high and rising in the Nordic region. While among women prevalence of OA was comparable to the global average, men had a higher prevalence than the global level. There were persistent increases in the age-standardized rates of OA burden with time. Furthermore, OA was responsible for a higher proportional burden of total DALYs in the Nordic region compared with the global level. Among the top 30 leading causes of YLDs in the region, OA had the 5th greatest relative increase in total YLDs from 1990 to 2015. In all Nordic countries but Denmark the observed OA burden was lower than expected based on sociodemographic status, but worryingly this gap between the observed and expected number of YLDs is closing. Current trends in population growth, aging, and prevalence of overweight and obesity will lead to a further increase in OA burden in coming years and call for incorporating OA prevention and treatment as a priority in health policies in the Nordic region.

Supplementary data

Table 3 and Figures S1–S5 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1404791.

AAK participated in the design, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation of results and drafting the manuscript. LSL, MM-L, IFP, and ME participated in interpretation of results, and revision of the manuscript.

Acta thanks Lars Vatten and Maiju Welling for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- Asgeirsdottir T L, Gerdtham U G.. Health behavior in the Nordic countries. Nordic J Health Economics 2016; 1: 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs A M, Cross M J, Hoy D G, Sanchez-Riera L, Blyth F M, Woolf A D, March L.. Musculoskeletal health conditions represent a global threat to healthy aging: A report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health. Gerontologist 2016; 56(Suppl2): S243–S55. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyere O, Cooper C, Pelletier J P, Branco J, Luisa Brandi M, Guillemin F, Hochberg M C, Kanis J A, Kvien T K, Martel-Pelletier J, Rizzoli R, Silverman S, Reginster J Y.. An algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis in Europe and internationally: A report from a task force of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 44 (3): 253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft P. The occurrence of osteoarthritis outside Europe. Ann Rheum Dis 1996; 55 (9): 661–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Williams S, Guillemin F, Hill C L, Laslett L L, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Osborne R, Vos T, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L.. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73 (7): 1323–30. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 DALYs and HALE Collaborators Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388 (10053): 1603–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31460-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388 (10053): 1545–602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388 (10053): 1459–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388 (10053): 1659–724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiligsmann M, Reginster J Y.. The economic weight of osteoarthritis in Europe. Medicographia 2013; 35: 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kiadaliri A A, Lamm C J, de Verdier M G, Engstrom G, Turkiewicz A, Lohmander L S, Englund M.. Association of knee pain and different definitions of knee osteoarthritis with health-related quality of life: a population-based cohort study in southern Sweden. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016; 14 (1): 121. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0525-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen J, Eskelinen A, Huhtala H, Paavolainen P, Remes V.. The incidence of knee arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis grows rapidly among baby boomers: A population-based study in Finland. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64 (2): 423–8. doi: 10.1002/art.33367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody G M, Brooks P M.. Improving musculoskeletal health: Global issues. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012; 26 (2): 237–49. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi-Lakeh M, Forouzanfar M H, Vollset S E, et al. . Burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 1990–2013: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Ann Rheum Dis 2017. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C, Lopez A.. The global burden of disease: A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nemes S, Rolfson O, A W D, Garellick G, Sundberg M, Karrholm J, Robertsson O.. Historical view and future demand for knee arthroplasty in Sweden. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (4): 426–31. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2015.1034608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neogi T, Zhang Y.. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2013; 39 (1): 1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen U S, Zhang Y, Zhu Y, Niu J, Zhang B, Felson D T.. Increasing prevalence of knee pain and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: Survey and cohort data. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155 (11): 725–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-11-201112060-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemelainen M J, Mäkelä K T, Robertsson O, W–Dahl A, Furnes O, Fenstad A M, Pedersen A B, Schroder H M, Huhtala H, Eskelinen A.. Different incidences of knee arthroplasty in the Nordic countries. Acta Orthop 2017: Acta Orthop 2017; 88(2): 173–8. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2016.1275200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson I F, Jacobsson L T.. Osteoarthritis of the peripheral joints. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2002; 16 (5): 741–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M M, Cibere J, Goldsmith C H, Anis A H, Kopec J A.. Osteoarthritis incidence and trends in administrative health records from British Columbia, Canada. J Rheumatol 2014; 41 (6): 1147–54. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.131011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth V K, Fryer J L, Zhai G, Winzenberg T M, Hosmer D, Jones G.. A meta-analysis of sex differences prevalence, incidence and severity of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005; 13 (9): 769–81. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiewicz A, Petersson I F, Bjork J, Hawker G, Dahlberg L E, Lohmander L S, Englund M.. Current and future impact of osteoarthritis on health care: A population-based study with projections to year 2032. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22 (11): 1826–32. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace I J, Worthington S, Felson D T, Jurmain R D, Wren K T, Maijanen H, Woods R J, Lieberman D E.. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2017; 114 (35): 9332–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703856114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf A D, Erwin J, March L.. The need to address the burden of musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012; 26 (2): 183–224. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Peat G, Bedson J, Jordan K P.. Annual consultation incidence of osteoarthritis estimated from population-based health care data in England. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015; 54 (11): 2051–60. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.