Abstract

Background and purpose

A better understanding of the patterns and variation in initiation and progression of osteoarthritis (OA) in the knee may influence the design of therapies to prevent or slow disease progression. By studying cartilage from the human lateral femoral condyle (LFC), we aimed to: (1) assess specimen distribution into early, mild, moderate, and severe OA as per the established histopathological scoring systems (HHGS and OARSI); and (2) evaluate whether these 2 scoring systems provide sufficient tools for characterizing all the features and variation in patterns of OA.

Patients and methods

2 LFC osteochondral specimens (4 x 4 x 8 mm) were collected from 50 patients with idiopathic OA varus knee and radiographically preserved lateral compartment joint space undergoing total knee arthroplasty. These were fixed, sectioned, and stained with HE and Safranin O-Fast Green (SafO).

Results

The histopathological OA severity distribution of the 100 specimens was: 6 early, 62 mild, 30 moderate, and 2 severe. Overall, 45/100 specimens were successfully scored by both HHGS and OARSI: 12 displayed low OA score and 33 displayed cartilage surface changes associated with other histopathological features. However, 55/100 samples exhibited low surface structure scores, but were deemed to be inadequately scored by HHGS and OARSI because of anomalous features in the deeper zones not accounted for by these systems: 27 exhibited both SafO and tidemark abnormal features, 16 exhibited only SafO abnormal features, and 12 exhibited tidemark abnormal features.

Interpretation

LFC specimens were scored as mild to moderate OA by HHGS and OARSI. Yet, several specimens exhibited deep zone anomalies while maintaining good surface structure, inconsistent with mild OA. Overall, a better classification of these anomalous histopathological features could help better understand idiopathic OA and potentially recognize different subgroups of disease.

Idiopathic osteoarthritis (OA) was initially perceived as a mechanical “wear and tear” process of articular cartilage that increased with age. Now, OA is recognized as whole-organ disease process influenced by multiple factors including body weight, diet, joint stability, alignment, joint and meniscus shape, and associated changes in local and systemic inflammatory mediators, genetic factors, and innate immunity (Greene and Loeser 2015, Orlowsky and Kraus 2015, Malfait 2016, Varady and Grodzinsky 2016).

A better understanding of the patterns and variation in initiation and progression of OA in the knee could influence the design and patient-specific selection of therapies to prevent or slow the progression of OA. The key challenge encountered in this process is our incomplete understanding of the underlying disease mechanism (Li et al. 2013). Although the order in which different OA phenomena occur is unclear, some of these changes can be readily identified by 2 validated cartilage histopathological scoring assessments (Rutgers et al. 2010): (1) the histologic/histochemical grading system (HHGS) (Mankin et al. 1971) and (2) the advanced Osteoarthritis Cartilage Histopathology Assessment System (OARSI) (Pritzker et al. 2006).

Previous studies have demonstrated that varus knee OA subjects have higher loading on the medial than lateral compartment, with joint space width (JSW) preserved in the latter (Kumar et al. 2013). A reduced joint load in people with knee OA is related to a slower progression of the disease (Sritharan et al. 2017). Thus, lower loads in the lateral compartment may result in slower OA progression at this site. Based on these observations, we designed this study to obtain cartilage specimens from the lateral femoral condyle (LFC) from patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with idiopathic OA varus knee, which presented relatively preserved JSW, with 2 aims: (1) to assess specimen distribution into early, mild, moderate, and severe OA as per the established histopathological scoring systems (HHGS and OARSI); and (2) to evaluate whether the HHGS and OARSI scoring systems provide sufficient tools for characterizing all the features and variation in patterns of primary OA progression.

Methods

50 patients (30 men) with a mean age of 63 (37–80) years and mean BMI of 31 (18–49) with varus knees scheduled for TKA were recruited after getting their informed consent. Inclusion criteria required patients with a diagnosis of idiopathic OA (primarily medial compartment and/or patellofemoral disease) exhibiting a relatively preserved lateral compartment (JSW: 2–10 mm, median: 6 mm in the lateral compartment) based on preoperative weight-bearing anterior-posterior radiographs taken in full extension and 30° of flexion. Patients were excluded if they had secondary arthritis related to systemic inflammatory arthritis (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis); history of autoimmune disorders, gout or pseudogout, previous surgery to the index knee, current or previous treatment with systemic glucocorticoids or osteotropic medication; current treatment or treatment of cancer within previous 2 years; known or suspected infection; and osteonecrosis.

Cartilage procurement

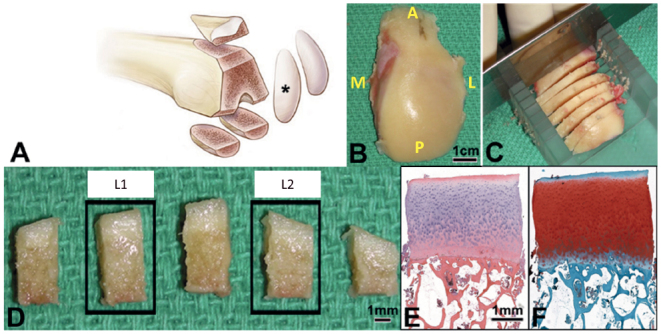

During TKA, the LFC was collected after making the distal femoral cut and the AP orientation was noted. All included LFC specimens presented with Grade 0 (normal), Grade I (cartilage with softening and swelling), or Grade II (a partial-thickness defect with fissures on the surface that do not reach subchondral bone (SCB) or exceed 1.5 cm in diameter) macroscopic Outerbridge classifications (Outerbridge 1961). 2 osteochondral specimens (4 × 4 × 8 mm) were prepared by placing the condyle in an in-house fabricated miter box in AP orientation. The miter box had evenly spaced slots, 4 mm apart on the top edge and cartilage arches were cut using a razor blade from the weight-bearing center portion of the LFC; 1 was located medial (L1) and 1 lateral (L2) to the LFC midline (Figure 1). The centers of these two samples were separated by 10 mm.

Figure 1.

Sample of lateral femoral condyle (black star) (right knee shown in example) was obtained (A, B). The orientation of the condyle was noted in the operating room (A = anterior; P = posterior; M = medial; L = lateral) and placed in an in-house fabricated miter box in AP orientation and cut into 4 mm thick arches through the region of the femur that is weight bearing in extension (C). The central region of 1 arch was cut into 5 specimens (4 mm x 4 mm), the second (Lateral) and fourth (Medial) were processed for histology (D). Each specimen was paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with HE (E), and SafO-FG (F) for analysis.

Histological sample processing and digital imaging

100 osteochondral specimens were processed from 50 patients. Immediately after surgical retrieval, specimens were fixed for 48 h at 4 °C (Scott 1989). 5µ thick paraffin sections were cut and stained with freshly prepared HE or SafraninO and fast green (SafO). The embedded tissue was cut in the plane perpendicular to the surface of the cartilage to obtain a representative overview of the tissue structure and thickness (Figure 1). Two adjacent sections per stain were digitally imaged at 10x and used for scoring using HHGS and advanced OARSI systems.

Disease severity distribution for all specimens

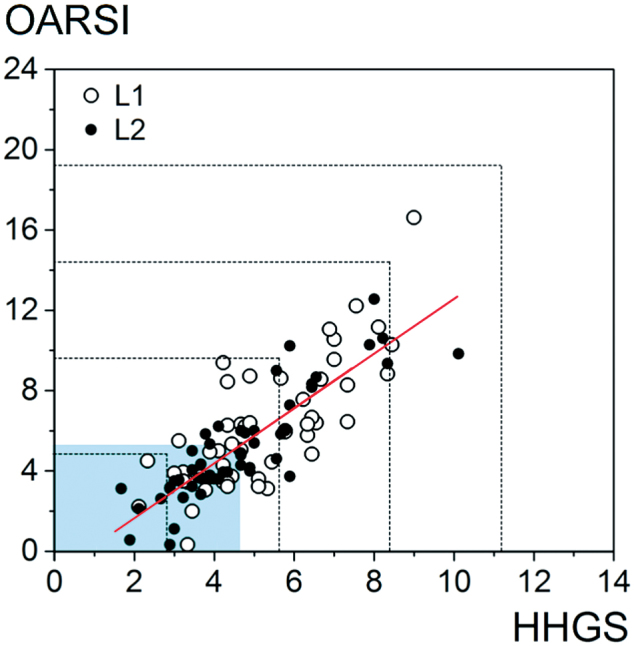

HHGS and OARSI score distribution was divided into 5 equal bins to classify specimens into early, mild, moderate, and severe OA (Figure 2, dotted lines).

Figure 2.

Correlation plot of average HHGS versus average OARSI scores for specimens from lateral and medial locations. Moderate correlation was observed between the 2 systems (Spearman’s coefficient =0.806). The total HHGS and OARSI scores were divided into 5 equal bins as indicated by the dotted lines, and classified as early, mild, moderate, and severe to assess specimen distribution. The shaded regions on the bottom and left represent the regions containing the 50% of samples with scores below the median for each scoring system (median HHGS =4.8, OARSI =5.5) where correlation between the systems is less robust. For illustration, the trend is represented by a red line from a fitted linear regression of OARSI on HHGS.

Percentage of specimens indicating features unaccounted for by either scoring systems

We classified samples as presenting unaccounted for features if the samples presented with low structure score (HHGS structure =1), but had substantial changes in SafO staining (HHGS SafO score >2) and tidemark features (HHGS tidemark score =0 or 1). Of the specimens binned by the aforementioned criteria, in order to quantify the percentage of samples presenting with the unaccounted for SafO and tidemark histological features, we systematically filtered samples as per the above conditions, and then individually classified these samples into yes/no decisions (yes = shows at least 1 of the unaccounted for features; no = does not show any features) based on at least 2 of the 3 reviewers’ agreement.

Statistics

To assess the association between histopathology scores and subjects’ age and sex, generalized linear models were fit, with the histopathology score as the dependent variable and age and sex as independent variables. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were estimated to assess the association of HHGS and OARSI mean total scores. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were constructed using Fisher’s z-transformation (for each side separately) or the percentile bootstrap (when lateral and medial sides were pooled).

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board committee of the Cleveland Clinic (Protocol:13641) and was supported by a National Institute of Health grant (R01AR063733) awarded to GFM. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Results

Disease severity distribution

The distribution of histopathology severity exhibited by this LFC sample cohort appeared strongly skewed to earlier stages of OA, though none were scored as normal or as severe OA (Figure 2). It was noted that 6% of our samples were considered early, 62% were mild, 30% were moderate, and 2% were binned as severe OA. The histopathology scores were distributed similarly across age and sex.

When the scores from all the readers were averaged, the Spearman’s coefficient was moderate (0.8, CI:0.8, 0.9) (Figure 2). The correlation between HHGS and OARSI scores below the median values (4.8 and 5.5, respectively) was calculated to be weaker than the full range.

Features unaccounted for by either scoring system

Using both HHGS and OARSI histopathological scoring systems, 45/100 specimens were categorized adequately: 12/100 displayed low scores (structure =1) and 33/100 displayed surface degradation (structure >2) along with other histopathological changes (Figure 3). However, 55/100 specimens were inadequately scored by either of the 2 histopathological systems, especially in regard to SafO staining and tidemark changes, which were not associated with substantial surface changes (structure =1 or less). Of the 55 specimens, 27/55 displayed both abnormal SafO and tidemark features, 16/55 displayed abnormal SafO features only, and 12/55 displayed abnormal tidemark features only.

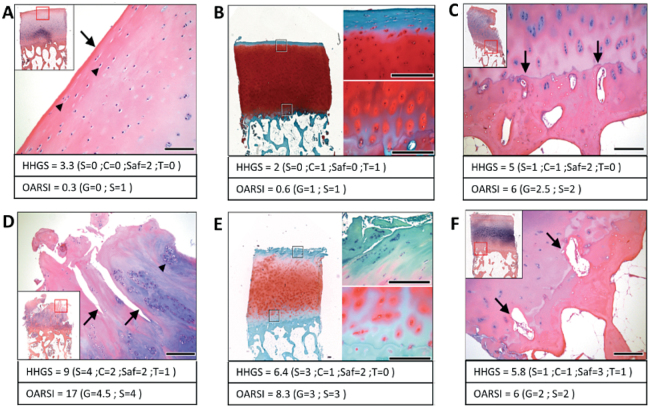

Figure 3.

Representative HE and SafO stained images of cartilage specimens obtained from the lateral femoral condyle. Top panel images indicate histopathological features found in “normal” cartilage, showing normal surface and cells (A), uniform safraninO staining (B) and single undulating tidemark not breached by blood vessels (C). Bottom panel images suggest typical osteoarthritic cartilage features, where surface shows fissures (D), hypercellularity, and cloning associated with fissures (D, E) and tidemark breached by blood vessels (F).

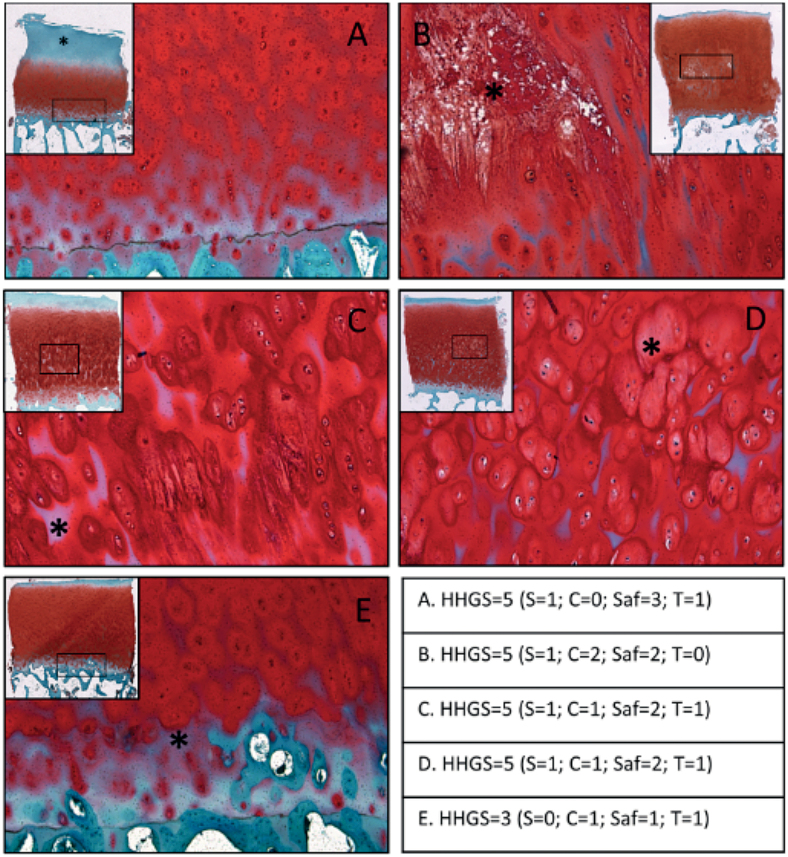

For instance, Figure 4A shows a loss of SafO stain in the top half of the tissue that is not associated with surface erosion or fissures. Figure 4B shows tissue necrosis/matrix degradation in the radial zone, accompanied by some loss of SafO stain in the inter-territorial matrix region that is not associated with obvious signs of surface erosion. Figure 4C shows loss of SafO stain in the inter-territorial matrix, mainly confined to the bottom half of the tissue section (well within the radial zone). Complete loss of SafO stain is seen in the top region of this sample, but no major surface erosion or fissures are observed. Figure 4D shows varying staining patterns seen in the territorial matrix region and no SafO stain observed in some inter-territorial regions in the radial zone. Figure 4E shows that there are some changes starting to appear near the tidemark even when the rest of the cartilage features appear relatively normal. The number of specimens in this study that exhibited at least 1 of the above-described SafO features represented 43/100 specimens.

Figure 4.

Representative images of cartilage obtained from the lateral femoral condyle that indicate the unaccounted histopathological safraninO features: (A) loss of SafO stain in the top half of the tissue that is not associated with much surface erosion or fissures; (B) tissue necrosis/degradation in the radial zone, accompanied by some loss of SafO stain in the inter-territorial matrix region; (C) loss of SafO stain in the inter-territorial matrix, mainly confined to the bottom half of the tissue section; (D) varying staining patterns seen in the territorial matrix region and no SafO stain observed in some inter-territorial regions in the radial zone; (E) SafO staining loss near the tidemark even when the rest of the cartilage features appear relatively normal. The table indicates the total HHGS scores for each individual specimen, along with structure score (S), cell score (C), safraninO/fast green score (Saf), tidemark score (T). 43% of sample cohort presented with at least one feature.

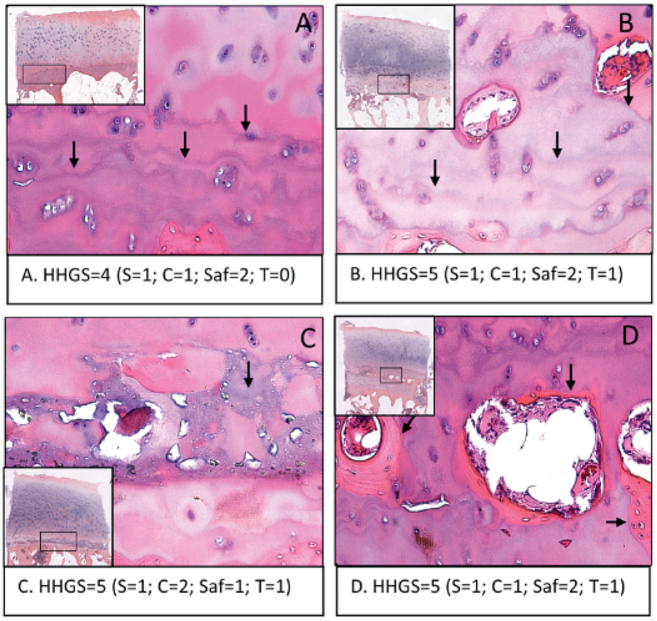

Only HHGS scoring evaluates tidemark features, while OARSI does not apply scoring criteria for the tidemark. The current HHGS scoring system has a score of either 0 or 1 that is determined by a blood-vessel breach, but we have found other tidemark features not considered by HHGS. Figure 5A shows the formation of multiple tidemarks, and Figure 5B shows multiple tidemarks that are breached by multiple blood vessels. Figure 5C exhibits an unspecified tissue composition deposited near the tidemark, which stains significantly differently from normal hyaline cartilage and bone tissue. Figure 5D shows the formation of bone tissue well within the hyaline cartilage region resulting in the appearance of cartilage–bone–cartilage–bone interleaved tissue layers accompanied by multiple tidemarks. The number of specimens in this study that exhibited at least 1 of the above-described features represented 39/100 specimens.

Figure 5.

Representative images of cartilage obtained from the lateral femoral condyle that indicate the unaccounted tidemark-related features as seen in the HE stained sections: (A) multiple tidemarks; (B) multiple tidemarks that are breached by multiple blood vessels; (C) unknown tissue composition deposited near the tidemark, which stains significantly differently from normal hyaline cartilage and bone tissue; (D) formation of bone tissue well within the hyaline cartilage region resulting in the appearance of cartilage–bone–cartilage–bone interleaved tissue layers accompanied by multiple tidemarks. The table indicates the total HHGS scores for each individual specimen, along with structure score (S), cell score (C), safraninO/fast green score (Saf), tidemark score (T). 39% of the sample cohort presented with at least 1 feature.

Other noteworthy observations of the histological features of osteochondral specimens from LFC include: (1) infrequent occurrence of pannus-like synovial tissue overgrowth on cartilage surface (2%); (2) relatively low incidence of hypocellularity (6%), often in the deep zone even when upper-zone chondrocytes were reasonably well preserved; and (3) frequent observation of hypercellularity in the top third of the hyaline cartilage tissue, though it was not uncommon for this to appear in the middle or deep zones as well.

Discussion

Human idiopathic OA is a gradually progressing and disabling condition, with a combination of disease stages and cellular responses that are incompletely understood (Goldring and Goldring 2016). This, and the fact that mostly severe human OA cartilage specimens are readily available for research, makes understanding of the disease mechanism and prediction of the disease development a challenging task.

The main finding of this study was that histological assessment of osteochondral specimens from human LFC in varus knees, with relatively preserved lateral compartment JSW, revealed that 45/100 specimens were categorized adequately using 2 traditional histopathological scoring systems: 12/100 displayed low HHGS and OARSI scores and 33/100 displayed surface degradation along with other histopathological changes. However, 55/100 of the specimens exhibited histopathological features in the deep zone (e.g. loss of chondrocytes, loss of SafO stained matrix, multiple tidemarks, and SCB eruptions into the deep zone), while exhibiting good surface structure, and were not adequately assessed with the 2 current scoring systems. Inability to account for these deep-zone histopathological features along with an over-emphasized assessment of surface structure in the current scoring systems resulted in both HHGS and OARSI categorizing these specimens into early to mild OA categories, which we contend are quite possibly erroneous. We believe that the cartilage samples from this relatively large cohort of patients with idiopathic OA bring to attention histopathological features that we still need to understand, particularly if recent contentions of OA subtypes are valid (Karsdal et al. 2014, Wyatt et al. 2016). The cartilage procurement method in this study presents suitable samples exhibiting the above-mentioned histopathological features, and may help to better understand early, mild, and moderate histopathological OA changes (Sritharan et al. 2017). Our findings contribute to new details and provide well-documented evidence of unreported histopathological changes observed during OA progression, especially in cartilage tissue compartments that are under low mechanical impact. A high prevalence of deep-zone and SCB alterations were seen despite the absence of substantial surface structure degradation. We are currently developing a modified HHGS system that should accommodate all of the anomalous histopathological features we observed.

Careful assessment of these specimens revealed that a large subset of our cohort exhibited unaccounted for extra-cellular matrix degradation features and tidemark-related features (43% and 39%, respectively). When assessing the specimens using the traditional scoring systems, the major difference between the HHGS and OARSI system is that OARSI does not take into account changes in the deep zone independent of any observed changes in the superficial zone. Thus, tidemark alterations, death of chondrocytes in the deep zone, loss of SafO staining in the deep zone, and SCB alterations are not accounted for in OARSI if there are no associated surface structural changes. Since over half of our samples exhibited these deep-zone alterations without substantial alteration in surface structure, OARSI was unable to render a fully accurate histopathological score for these types of samples. None of the features described as abnormal features in our study have been demonstrated in normal cartilage histology (Pauli et al. 2012) and thus are definitely attributes of disease.

Using the HHGS score range distribution for early, mild, moderate, and severe OA (Table) defined by Ostergaard et al. (1999), none of our samples were considered as early OA, 58% ranked as mild, 42% ranked as moderate, and none were ranked as severe. Assuming a linear correlation between HHGS and OARSI, as determined in our study and noted by others (Ostergaard et al. 1999, Pauli et al. 2012), we calculated the OARSI score distribution range for our sample cohort and found that 14% would be considered early OA, 78% considered mild OA, 8% considered moderate OA, and none considered severe OA (Table).

Many of the features we found have been mentioned in the literature to be associated with various stages and subtypes of OA progression, yet to date none of these features have been considered in the existing scoring systems. Loss of territorial matrix and inter-territorial matrix surrounding deep-zone chondrocytes has been reported (Maldonado and Nam 2013). In the mechanically loaded joint space, changes have been reported to start near the superficial zone, as it is most susceptible to mechanical injury (Caramés et al. 2012). Yet, a majority of our observations in regard to territorial and inter-territorial matrix loss were confined to the bottom half of the cartilage thickness. Another speculated mechanism of loss of matrix near the bottom half of the cartilage is due to changes in thickness, volume, and stiffness of SCB (Sritharan et al. 2017). We also had LFC specimens that demonstrated a near complete loss of SafO staining in the top half, but the cartilage surface remained relatively free of fissures, likely a result of the predicted lower mechanical loads in the lateral compartment of the knee (Kumar et al. 2013, Scott et al. 2013).

In regard to features seen near the tidemark, it has been reported that a duplication of tidemark is associated with vascular invasion (Bullough 2004). Such a process is usually followed by an advancement of calcified cartilage into the deep zone of articular cartilage. In the late stages of OA, the penetration of vascular elements into the hyaline cartilage zone leads to bone formation around these blood vessels. Loss of proteoglycans in the deep zone has been associated with subsequent invasion into these tissue locations by blood vessels (Mapp and Walsh 2012). Chondrocytes also have a high tendency to be metabolically activated in proteoglycan-depleted matrix (Suri and Walsh 2012). As a result, blood-vessel breach is more feasible, followed by bone formation long term (Maes 2017).

To date, structure-modifying treatments for OA have been disappointing (Karsdal et al. 2016). Karsdal et al. advocated for the need to segregate patients with different OA subtypes to pair them with an optimal mode of treatment to yield an effective intervention. A possible reason for poor translation to clinical practice is that many preclinical studies involve posttraumatic OA, which accounts for only 12% of symptomatic OA (Brown et al. 2006) and exhibits a different pathophysiology from idiopathic OA. If the current contention of OA subtypes is valid, then future improvements to OA histological scoring systems will need to incorporate a better balance and definitions for changes in cellular response (Poole 1997, Lotz et al. 2010), extracellular matrix (Favero et al. 2015), tidemark and SCB (Lane and Bullough 1980). Our study provides a robust and consistent model to study human idiopathic OA in the knee to contribute to the present challenges.

Our study has multiple limitations, the major one being inaccessibility to normal human cartilage sample to compare our observations. The level of patello-femoral disease and integrity of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments were not routinely assessed intraoperatively. Future studies and analysis will need to focus on better characterizing the histopathological features by immunohistochemical staining for specific antigens like collagen type I, II, or X. A broader array of staining techniques may be considered to enhance the depth of data regarding underlying biological function at a cell and matrix level (Changoor et al. 2011). Gene expression and protein analysis can also be performed to correlate with histopathological observations and finally correlating the characteristics of the progenitors in terms of their biological potential to regenerate cartilage.

Conclusions

Some suggested areas of improvement for assessing OA pathological features include: (1) a better balance between the different features of the scoring systems so no one parameter (structure, cells, SafO, tidemark) is over-weighted with respect to the other parameters; (2) clear and specific instructions to distinguish the scores within each of the 4 major conventional parameters; and (3) provide a validated, online image database and simplified diagrammatic representations of these images so raters of all experience levels would achieve a better consensus opinion and decrease scoring disparities. Implementations of these approaches should potentially increase standardization among histopathological scoring systems, increase precision and rigor, and allow documentation of unaccounted for anomalies that might shed light on subgroup identification or different patterns of progression of OA.

The authors would like to acknowledge the histological processing skills of Edward Uhl in the Histochemistry Core Facility in the Biomedical Engineering Department (Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic).

Conception of study: GM, RJM. Study design, acquisition of data, data analyses: VPM, NP, TZ, RJM. Statistical analysis and interpretation: NO, VPM. Drafting of the article: VPM. Critical revising for important intellectual content: NP, RJM, GFM.

Acta thanks Anders Troelsen and other anonymous reviwers for help with peer review of this study.

Distribution of specimen cohort into early, mild, moderate, and severe OA as per the Ostergaard et al. (1999) classification of HHGS scores. OARSI score range was extrapolated from HHGS scores assuming linear correlation

| OA stage | HHGS score | Specimen distribution | OARSI score | Specimen distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | < 2 | 0 | < 3.4 | 14% |

| Mild | 2–5 | 58% | 3.4–8.6 | 78% |

| Moderate | 6–9 | 42% | 8.6–15.4 | 8% |

| Severe | 10–14 | 0 | 15.4–24 | 0 |

References

- Brown T D, Johnston R C, Saltzman C L, Marsh J L, Buckwalter J A.. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: A first estimate of incidence, prevalence, and burden of disease. J Orthop Trauma. 2006; 20 (10): 739–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough P G. The role of joint architecture in the etiology of arthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004; 12 (Suppl): 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caramés B, Taniguchi N, Seino D, Blanco F J, D’Lima D, Lotz M.. Mechanical injury suppresses autophagy regulators and pharmacologic activation of autophagy results in chondroprotection. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64 (4): 1182–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changoor A, Tran-Khanh N, Méthot S, Garon M, Hurtig M B, Shive M S, Buschmann M D.. A polarized light microscopy method for accurate and reliable grading of collagen organization in cartilage repair. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011; 19 (1): 126–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favero M, Ramonda R, Goldring M B, Goldring S R, Punzi L.. Early knee osteoarthritis: Figure 1. RMD Open [Internet] 2015; 1 (Suppl 1): e000062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring S R, Goldring M B.. Changes in the osteochondral unit during osteoarthritis: Structure, function and cartilage-bone crosstalk. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016; 12 (11): 632–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene M A, Loeser R F.. Aging-related inflammation in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015; 23 (11): 1966–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal M A, Christiansen C, Ladel C, Henriksen K, Kraus V B, Bay-Jensen A C.. Osteoarthritis: A case for personalized health care? Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22 (1): 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsdal M A, Michaelis M, Ladel C, Siebuhr A S, Bihlet A R, Andersen J R, Guehring H, Christiansen C, Bay-Jensen A C, Kraus V B.. Disease-modifying treatments for osteoarthritis (DMOADs) of the knee and hip: Lessons learned from failures and opportunities for the future. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016; 24 (12): 2013–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar D, Manal K T, Rudolph K S.. Knee joint loading during gait in healthy controls and individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21 (2): 298–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane L B, Bullough P G.. Age-related changes in the thickness of the calcified zone and the number of tidemarks in adult human articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1980; 62 (3): 372–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Yin J, Gao J, Cheng TS, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, Zheng MH.. Subchondral bone in osteoarthritis: insight into risk factors and microstructural changes. Arthritis Res Ther 2013; 15(6): 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz M K, Otsuki S, Grogan S P, Sah R, Terkeltaub R, D’Lima D.. Cartilage cell clusters. Arthritis Rheumatol 2010; 62 (8): 2206–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C. Signaling pathways effecting crosstalk between cartilage and adjacent tissues. Seminars in cell and developmental biology: The biology and pathology of cartilage. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2017; 62: 16–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado M, Nam J.. The role of changes in extracellular matrix of cartilage in the presence of inflammation on the pathology of osteoarthritis. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 284873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfait A M. Osteoarthritis year in review 2015: Biology. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016; 24 (1): 21–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankin H J, Dorfman H, Lippiello L, Zarins A.. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1971; 53 (3): 523–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapp P I, Walsh D A.. Mechanisms and targets of angiogenesis and nerve growth in osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012; 8 (7): 390–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowsky E W, Kraus V B.. The role of innate immunity in osteoarthritis: When our first line of defense goes on the offensive. J Rheumatol 2015; 42 (3): 363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostergaard K, Andersen C B, Petersen J, Bendtzen K, Salter D M.. Validity of histopathological grading of articular cartilage from osteoarthritic knee joints. Ann Rheum Dis 1999; 58 (4): 208–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outerbridge R. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1961; 43-B: 752–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli C, Whiteside R, Heras F L, Nesic D, Koziol J, Grogan S P, Matyas J, Pritzker K P H, D’Lima D D, Lotz M K.. Comparison of cartilage histopathology assessment systems on human knee joints at all stages of osteoarthritis development. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20 (6): 476–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole C A. Articular cartilage chondrons: Form, function and failure. J Anat 1997; 191 (Pt 1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritzker K P H, Gay S, Jimenez S A, Ostergaard K, Pelletier J P, Revell K, Salter D, van den Berg W B.. Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: Grading and staging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006; 14 (1): 13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutgers M, van Pelt M J P, Dhert W J A, Creemers L B, Saris D B F.. Evaluation of histological scoring systems for tissue-engineered, repaired and osteoarthritic cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010; 18 (1): 12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J E. Cetylpyridinium chloride as a fixative for glycosaminoglycans in histologic sections. Arch Dermatol 1989; 125 (7): 1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C E H, Nutton R W, Biant L C.. Lateral compartment osteoarthritis of the knee: Biomechanics and surgical management of end-stage disease. Bone Joint J 2013; 95B (4): 436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sritharan P, Lin Y C, Richardson S E, Crossley K M, Birmingham T B, Pandy M G.. Musculoskeletal loading in the symptomatic and asymptomatic knees of middle-aged osteoarthritis patients. J Orthop Res 2017; 35 (2): 321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suri S, Walsh D A.. Osteochondral alterations in osteoarthritis. Bone 2012; 51 (2): 204–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varady N H, Grodzinsky A J.. Osteoarthritis year in review 2015: Mechanics. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016; 24 (1): 27–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt L A, Moreton B J, Mapp P I, Wilson D, Hill R, Ferguson E, Scammell B E, Walsh D A.. Histopathological subgroups in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016; 25 (1): 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]