Abstract

Background and purpose

A large number of fixation methods of hamstring tendon autograft (HT) are available for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR). Some studies report an association between fixation method and the risk of revision ACLR. We compared the risk of revision of various femoral and tibial fixation methods used for HT in Scandinavia 2004–2011.

Patients and methods

A register-based study of 38,666 patients undergoing primary ACLRs with HT, with 1,042 revision ACLRs. The overall median follow-up time was 2.8 (0–8) years. Fixation devices used in a small number of patients were grouped according to design and the point of fixation.

Results

The most common fixation methods were Endobutton (36%) and Rigidfix (31%) in the femur; and interference screw (48%) and Intrafix (34%) in the tibia. In a multivariable Cox regression model, the transfemoral fixations Rigidfix and Transfix had a lower risk of revision (HR 0.7 [95% CI 0.6–0.8] and 0.7 [CI 0.6–0.9] respectively) compared with Endobutton. In the tibia the retro interference screw had a higher risk of revision (HR 1.9 [CI 1.3–2.9]) compared with an interference screw.

Interpretation

The choice of graft fixation influences the risk of revision after primary ACLR with hamstring tendon autograft.

The most commonly used grafts in Scandinavia for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) are hamstring tendon autografts (HT) or patellar tendon autografts (Granan et al. 2009). There are multiple devices available on the market for fixation of the graft. Most devices have been evaluated mechanically tested with acceptable results (Ahmad et al. 2004, Milano et al. 2006, Aga et al. 2013). Numerous clinical studies have found similar objective or subjective outcomes comparing different fixation techniques (Laxdal et al. 2006, Rose et al. 2006, Moisala et al. 2008, Myers et al. 2008, Harilainen and Sandelin 2009, Drogset et al. 2011, Frosch et al. 2012, Gifstad et al. 2014). Hence, there is no definite recommendation for the best fixation technique and the surgeon’s choice of fixation is likely to be influenced by personal experience, local traditions, and possibly marketing from the industry.

A recent study (Persson et al. 2015) from the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry (NKLR) identified combinations of fixations for HT with increased risk of revision at 2 years. In addition, a higher risk of revision when using cortical buttons compared with transfemoral or intratunnel fixations in the femur was observed. These findings call into question the increasing use of cortical buttons for HT fixation (Ahlden et al. 2012). In addition, Andernord et al. (2014) found a reduced risk of early revision when a metal interference screw was used to fixate semitendinosus grafts in the tibia.

This study further investigates the risk of revision for the most common fixation techniques and devices in HT reconstructions during the period 2004–2011, using a combined dataset from all 3 Scandinavian ACL registries (the NKLR, the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Registry, and the Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Register).

Materials and methods

Data sources

The Scandinavian knee ligament registries were established in 2004–2005 and are similar in design (Granan et al. 2008, Ahlden et al. 2012, Rahr-Wagner and Lind 2016). Patient-specific data (sex, age, previous surgery/injuries to index or contralateral knee), surgical details (graft choice, fixation choice, potential treatment of other ligament injuries or meniscal/cartilage injuries) and intraoperative findings (meniscal and cartilage injuries and signs of arthrosis) are reported at the time of surgery. Patients are followed prospectively with revision ACLR, subsequent surgery to the index knee, and patient-reported outcome (Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years follow-up) as endpoints. The report rates to the registries are similar, from 86% to ≥90% (Ytterstad et al. 2012, Rahr-Wagner et al. 2013a, www.aclregister.nu 2014).

This study includes all 38,666 patients registered from the start of the Scandinavian registries up to December 31, 2011, with a primary ACLR with an HT. The following data were considered in the study: date of primary and potential revision reconstruction, patient age and sex, fixation of the graft in femur and tibia, activity at primary injury, location (right/left knee), meniscal injury or treatment (yes/no), cartilage injury (yes/no), medial collateral injury (yes/no), and other concomitant injuries (fractures, nerve injuries, and vascular injuries). Patients with concomitant ligament injuries treated surgically were not included.

Exposure

We analyzed the revision rate and risk dependent on what tibial and femoral fixation device was used in the primary ALCR. The fixation device in the femur and tibia was either registered by the catalogue number of each device by using the unique bar-code sticker delivered by the manufacturer, or reported manually by the surgeon with either the registered trademark name of the device or a description of the fixation design, such as interference screw. Devices used in fewer than 500 patients were grouped according to their design and point of graft fixation. The femoral devices in the dataset were grouped as: cortical fixation (Endobutton [Smith & Nephew] or other), transfemoral fixation (Rigidfix [DePuy Mitek], Transfix [Arthrex] or other), interference screw, or other/unknown. The tibial devices in the dataset were grouped as: cortical fixation, interference screw, Intrafix (DePuy Mitek), retro interference screw, Rigidfix (DePuy Mitek), or other/unknown.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software version 22 (SPSS Inc, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). All tests were 2-sided with a 0.05 significance level.

Unadjusted cumulative implant revision curves were established using Kaplan–Meier estimates and crude 2- and 5-year revision percentages are reported. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated in Cox regression analyses. The multivariable analyses were stratified for country. The assumption of proportional hazards of the Cox regression model was evaluated with log–log plot and was found suitable. All survival analyses were performed with revision as the endpoint. No data were received on death or emigration. Patients were at risk and followed until revision or end of study.

Confounding factors

Patient age (5-year categories) at the time of the primary reconstruction, sex, meniscal injury to 1 or both menisci (yes/no), cartilage injury (yes/no), and activity at primary injury (pivoting activity [soccer, team handball, alpine activities]/other activities) were considered as possible confounding factors as these are potential risk factors for revision and may also influence the choice of fixation method. Further, none of the factors were considered as possible mediating variables. Additional analyses showed that meniscal injury and cartilage injury was not associated with, and thus did not inform, the fixation method. They were therefore not entered into the multivariable Cox regression analysis. Additional adjustment was made for corresponding fixation in the tibia when analyzing femoral fixations and for corresponding fixation in the femur when analyzing tibial fixations.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

Informed consent has been signed by all the participants in the NKLR, and the NKLR is approved by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate. No written consent is necessary in Denmark and Sweden for national healthcare registries. The study was funded by a grant from the Norwegian Orthopedic association.

LE has received course honoraria from Smith & Nephew, a fellowship grant from Arthrex to his institution, royalties for making of tools from Arthrex, and travel/accommodation expenses covered or reimbursed by Smith & Nephew for Multiligament course in Vail.

Results

The mean age at surgery was 28 years, and 57% were men. The median time from initial injury to the time of primary ACLR was 8 months (range 0–45 years). The most commonly used fixations in the femur were the Endobutton and Rigidfix, used in 14,106 and 12,041 patients respectively. The most commonly used tibial fixations were interference screw and Intrafix, used in 18,640 and 13,014 patients respectively. The median overall follow-up time was 2.8 (1.8–4.3) years (Table 1). The most commonly used combinations of fixations (femoral x tibial) were Rigidfix x Intrafix and Endobutton x Interference screw, used in 8,023 and 8,006 patients respectively (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics and baseline epidemiology. Values are percentages unless otherwise specified

| Femoral fixation | Cortical fixation |

Transfemoral fixation |

Interference screw | Other/ unknown | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endobutton | Other | Rigidfix | Transfix | Other | |||

| n | 14,106 | 4,352 | 12,041 | 3,652 | 520 | 3,453 | 542 |

| Age, mean (SD) a,b | 27 (10) | 28 (11) | 29 (10) | 28 (10) | 28 (10) | 28 (10) | 28 (11) |

| Pivoting activity c | 66 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 72 | 67 | 64 |

| Male | 56 | 58 | 57 | 59 | 57 | 59 | 54 |

| MCL injury | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 3.3 |

| Menisc injury | 41 | 44 | 38 | 42 | 42 | 43 | 40 |

| Cartilage injury | 21 | 21 | 20 | 29 | 28 | 20 | 23 |

| Other injury | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Follow-up, mean (SD) b | 2.2 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.7) | 3.7 (1.8) | 3.9 (1.8) | 5.4 (2.0) | 3.0 (1.8) | 2.9 (2.1) |

| Tibial fixation | Cortical fixation | Interference screw | Retro inter- | Other/ unknown | |||

| Intrafix | ference screw | Rigidfix | |||||

| n | 4,814 | 18,640 | 13,014 | 508 | 867 | 823 | |

| Age, mean (SD) a,b | 27 (11) | 28 (10) | 29 (11) | 27 (10) | 27 (10) | 27 (11) | |

| Pivoting activity c | 65 | 66 | 67 | 63 | 59 | 66 | |

| Male | 55 | 58 | 58 | 58 | 54 | 57 | |

| MCL injury | 3.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.6 | 5.1 | |

| Meniscal injury | 43 | 43 | 37 | 46 | 37 | 45 | |

| Cartilage injury | 19 | 24 | 18 | 30 | 25 | 29 | |

| Other injury | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.9 | |

| Follow-up, mean (SD) b | 3.2 (2.0) | 2.7 (1.9) | 3.3 (1.9) | 3.3 (1.8) | 4.1 (1.7) | 2.8 (2.3) | |

At time of surgery.

Years.

At primary injury (soccer, team handball, alpine activities).

Table 2.

Combinations of fixations used in more than 500 patients

| Fixations (femoral x tibial) | n |

|---|---|

| Endobutton x interference screw | 8,006 |

| Endobutton x intrafix | 3,154 |

| Endobutton x cortical fixation | 2,541 |

| Other cortical x interference screw | 1,856 |

| Other cortical x cortical fixation | 1,483 |

| Other cortical x Intrafix | 948 |

| Rigidfix x Intrafix | 8,023 |

| Rigidfix x interference screw | 2,661 |

| Rigidfix x Rigidfix | 825 |

| Transfix x interference screw | 3,123 |

| Interference screw x interference screw | 2,859 |

| Other combinations (used in less than 500 patients) | 3,187 |

| Total | 38,666 |

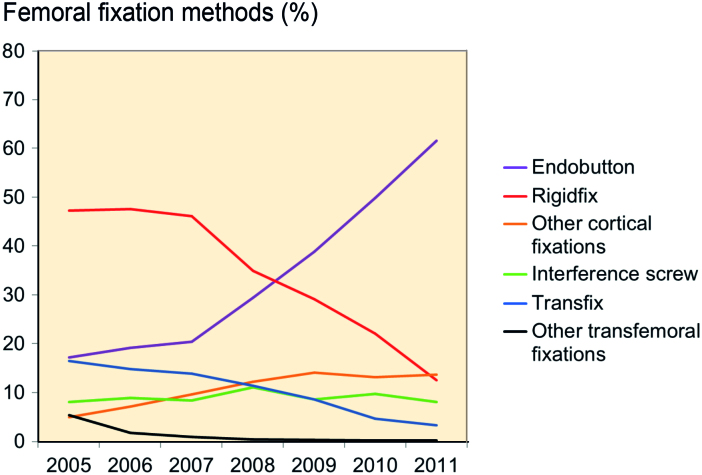

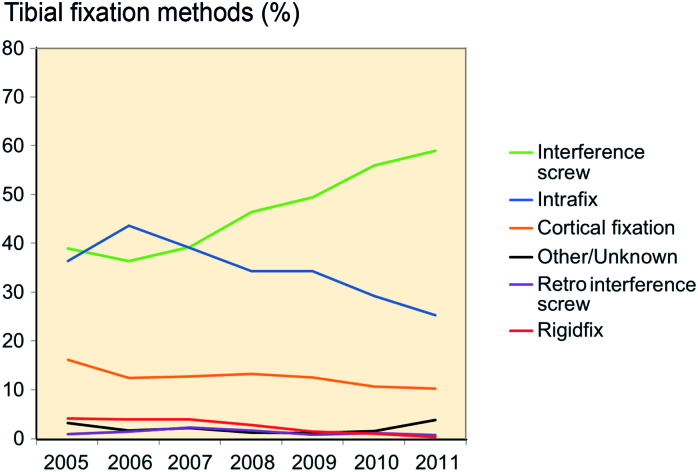

The use of femoral fixation with Endobutton increased during the entire study period while the usage of Rigidfix decreased after a peak in 2007 (Figure 1). The use of tibial fixation with interference screw increased after 2006 while the use of Intrafix decreased after a peak in 2006 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Femoral fixation in Scandinavia 20015–2011.

Figure 2.

Tibial fixation in Scandinavia 20015–2011.

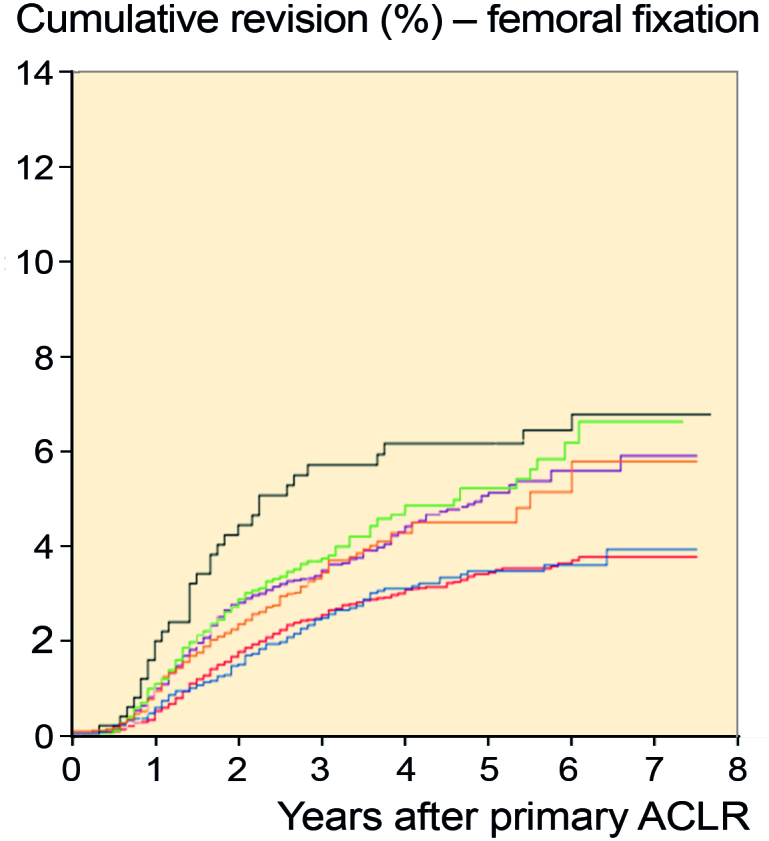

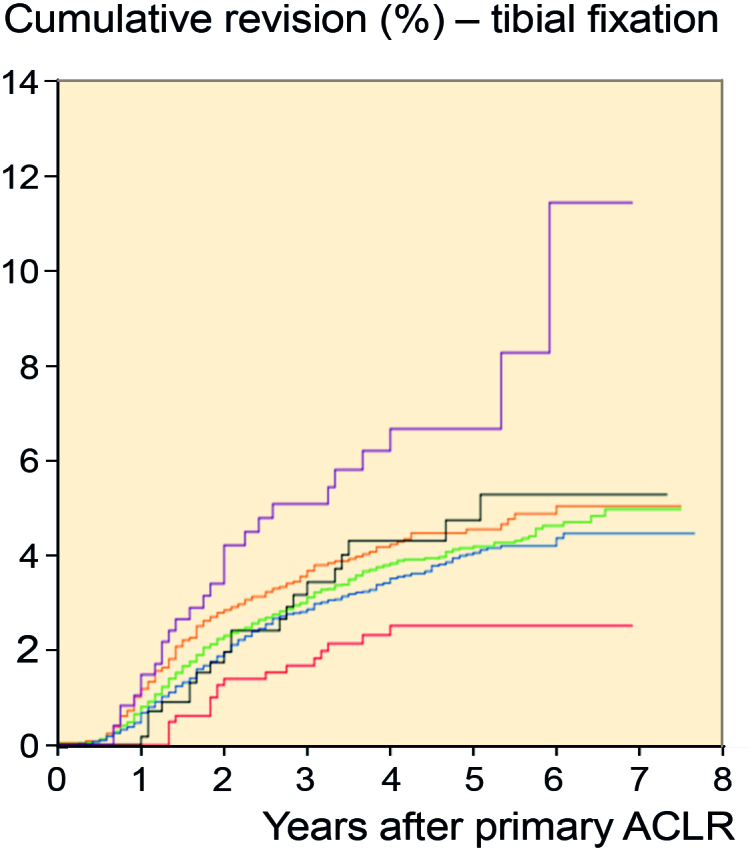

Revision rate during the first postoperative year was low (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Cumulative revision curve for femoral fixations.

Figure 4.

Cumulative revision curve for tibial fixations.

The 5-year revision rate according to femoral fixation was 5.0% (CI 4.4–5.7) for Endobutton, 3.4% (CI 3.0–3.8) for Rigidfix, and 3.5% (CI 2.8–4.1) for Transfix. For tibial fixation the 5-year revision rate was 4.2% (CI 3.7–4.6) for interference screw, 4.0% (CI 3.0–3.8) for Intrafix, and 2.5% (CI 1.4–3.7) for Rigidfix (Figures 3, 4 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Crude revision rates for patients within the examined groups of fixations at 2 and 5 years

| Revision rate (CI) % |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation point and group | n (revisions) | 2 years | 5 years |

| Femoral fixationa | |||

| Cortical fixation | |||

| Endobutton | 14,106 (342) | 2.7 (2.4–3.1) | 5.0 (4.4–5.7) |

| Other | 4,352 (115) | 2.2 (1.7–2.7) | 4.5 (3.6–5.4) |

| Transfemoral fixation | |||

| Rigidfix | 12,041 (316) | 1.7 (1.4–1.9) | 3.4 (3.0–3.8) |

| Transfix | 3,652 (100) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 3.5 (2.8–4.1) |

| Other | 520 (32) | 4.2 (2.5–6.0) | 6.1 (4.0–8.3) |

| Interference screw | 3,453 (119) | 2.7 (2.1–3.3) | 5.2 (4.2–6.2) |

| Other/unknown | 542 (18) | 2.7 (1.1–4.2) | 5.4 (2.7–8.0) |

| Tibial fixationb | |||

| Cortical fixation | 4,814 (159) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 4.6 (3.8–5.3) |

| Interference screw | 18,640 (462) | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 4.2 (3.7–4.6) |

| Intrafix | 13,014 (355) | 1.9 (1.6–2.1) | 4.0 (3.6–4.5) |

| Retro interference screw | 508 (27) | 3.4 (1.7–5.1) | 6.7 (4.1–9.3) |

| Rigidfix | 867 (18) | 1.3 (0.4–2.0) | 2.5 (1.4–3.7) |

| Other/unknown | 823 (21) | 1.8 (0.6–2.9) | 4.7 (2.7–6.8) |

Log-rank test for difference in overall revision between groups:

p-value <0.001

p-value =0.001

In the multivariable analysis, the HR for revision was 0.7 for the Rigidfix (CI 0.6–0.8) and Transfix (CI 0.6–0.9) groups compared with the Endobutton group and 1.9 (CI 1.3–2.9) for the group with the tibial fixation retro interference screw compared with the interference screw group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results (hazard ratios – HR) from the Cox regression models with revision as endpoint

| Fixation point and group | HR (CI) | Adjusted HR (CI) a |

|---|---|---|

| Femoral fixation | ||

| Cortical fixation | ||

| Endobutton | Ref. | Ref. |

| Other | 0.9 (0.8–1.2) | 0.8 (0.7–1.1) |

| Transfemoral fixation | ||

| Rigidfix | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.8) |

| Transfix | 0.7 (0.5–0.8) | 0.7 (0.6–0.9) |

| Other | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) |

| Interference screw | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| Other/unknown | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) |

| Tibial fixation | ||

| Cortical fixation | 1.1 (1.0–1.4) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) |

| Interference screw | Ref. | Ref. |

| Intrafix | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

| Retro interference screw | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 1.9 (1.3–2.9) |

| Rigidfix | 0.6 (0.3–0.9) | 0.9 (0.5–1.4) |

| Other/unknown | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

Adjusted analysis model stratified for country (Sweden, Denmark, Norway) and adjusted for gender, age at surgery (5-year categories), activity at primary injury, and corresponding fixation in tibia or femur.

Discussion

In this large multiregistry-based study from the Scandinavian countries, the main finding was that the HR for revision was reduced by 30% when using transfemoral fixation with Rigidfix or Transfix compared with cortical fixation with Endobutton, independent of the tibial fixation used. The hamstring tendon autograft was fixed with the cortical fixation Endobutton in one-third of the patients, with increasing use during the last years of the study period.

These results are in line with the recent findings of increased risk of revision within 2 years for cortical fixation compared with transfemoral fixation from the NKLR (Persson et al 2015). One can question the clinical relevance of a minor difference in revision risk. However, when clinical outcome after revision ACLR may be worse than after primary ACLR (Battaglia et al. 2007, Grassi et al. 2016), we believe the differences are of interest.

Previously, a variety of outcomes have been studied in clinical studies comparing different fixation devices and techniques (Drogset et al. 2005, Rose et al. 2006, Capuano et al. 2008, Moisala et al. 2008) with similar outcomes in the examined groups. However, there are a few clinical, biomechanical, and anatomical studies that have reported differences between different graft fixations in the femur. A recent meta-analysis by Browning et al. (2017) included 41 clinical level 1–4 studies comparing clinical outcome for patients treated with an ACLR with 4-strand hamstring autograft using either suspensory or aperture fixation. They found better arthrometric stability and fewer graft ruptures using suspensory compared with aperture fixation at a minimum of 2-year follow-up; however, they included graft fixation in the femur with cross-pins in the suspensory group. In a clinical trial of double-bundle ACLR, Ibrahim et al. (2015) found that 4 out of 32 patients with ACL grafts that were fixed in the femur with cortical fixation had >5 mm of postoperatively instrumented knee laxity compared with 0 out of 34 patients with transfemoral fixation at a mean follow-up of 2.5 years. They found no difference between the 2 groups in the Lachman and pivot-shift test. Frosch et al. (2012) compared, in a prospective non-randomized study, femoral fixation with bioabsorbable interference screws in 31 cases and bioabsorbable Rigidfix in 28 cases. They found similar subjective results but less side-to-side anterior translation as measured with a KT-1000 arthrometer in the cases with femoral fixation using Rigidfix.

Biomechanical studies most frequently investigate graft-fixation complex stiffness, pull-out strength, or graft–fixation complex lengthening after cyclic loading. Laxity of the graft–fixation complex and graft–tunnel motion might disturb the biologic incorporation of the graft in the bone tunnel (Hoher et al. 1998), leading to a weaker reconstruction. In a cadaver model measuring graft–fixation complex stiffness in double-looped semitendinosus grafts, To et al. (1999) found the stiffness of the graft and fixation complex to be dependent on the fixation method rather than the graft, with decreased stiffness when using a suture loop and a cortical button. Höher et al. (1998) found up to 3 mm of graft-tunnel motion when using a titanium button and polyester tape to fix quadruple hamstring grafts within the femoral bone tunnel. To further investigate the histological insertion point or the graft itself there is a need for more studies where samples are collected from revision ACLRs.

There has been a debate as to whether the surgical technique for femoral tunnel drilling affects the clinical outcome. Both Rigidfix and Transfix are likely to mainly have been fixed through a transtibial technique (TT) for drilling the femoral tunnel. TT has been shown to have a lower risk of revision compared with the anteromedial (AM) technique in a previous register study (Rahr-Wagner et al. 2013b). The authors argued that it could be due to the increased load on an anatomic reconstructed graft, due to potential problems with a shorter femoral tunnel or as a result of the surgeon’s learning curve when the new AM technique was introduced. However, they did not adjust for graft fixation in their analysis. Liu et al. (2015) found, in a systematic review, superior results for the AM technique based on physical examination, and it is possible that the mentioned difference in revision risk could be due to an unknown confounder, such as the graft fixation.

A change from transfemoral devices to cortical fixation has previously been reported from the Swedish ACL registry, probably as a result of the focus on anatomic ACL reconstruction using the AM technique (Ahlden et al. 2012). This tendency is also clear in our study.

Among the investigated tibial fixation devices the retro interference screw was the only device with a statistically significantly higher risk of revision compared with the interference screw. The retro interference screw (available in titanium or degradable poly-L-lactic acid [PLLA]) is placed retrogradely into the tibial bone tunnel from inside the joint. Although poor results have been reported in a previous biomechanical study (Scannell et al. 2015), and the possible risk of failure when using PLLA screws (Drogset et al. 2005, Persson et al. 2015) could explain the increased revision risk for the retro interference screw found in this study, we interpret the results with caution due to the small sample size. Further, we did not have data defining the material of the included retro interference screws and thus may not know whether this could have contributed to the inferior results.

A limited number of register studies have been conducted on the current topic. Andernord et al. (2014) found a statistically significant lower incidence of revision surgery when a metal interference screw was used in semitendinosus tendon autograft reconstructions compared with a bioabsorbable interference screw, AO screw, metal interference screw + staple, or Intrafix registered in the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Registry 2005–2011. This was, however, not found in the group with a combined semitendinosus and gracilis graft, which was used in four-fifths of the patients, in line with our results.

Strengths and weaknesses

The most important strength in this study is the large sample size of the groups investigated. A randomized controlled trial is difficult to conduct with enough statistical power to investigate a rare endpoint such as revision ACLR (Naylor and Guyatt 1996). A sample size calculation shows that 1,000 patients are needed in each group to detect a statistically significant difference in 2-year revision rates of 2.4% and 4.7%, equivalent to a hazard rate ratio of 2 (with a 2-sided 0.05 level and power of 80%). In general, prospective registry-based cohort studies are considered to be hypothesis-generating and not proving causality. However, in modern observational studies where potential biases are considered, estimates of treatment effects may be similar to those found in randomized controlled trials (Benson and Hartz 2000). Therefore, we believe our study to have a good methodology to investigate the risk of failure for different surgical techniques, such as choice of fixation method for the graft.

The baseline data of the Norwegian registry have been shown to be congruent with other registries (Maletis et al. 2011, Granan et al. 2012). Accordingly, we believe the results to be applicable not only to the countries where the study was conducted, but to a general orthopedic community.

We acknowledge the existing weaknesses of this study. For the smallest patient groups our results might be influenced by hospital-dependent revision rates. Experienced surgeons at large-volume clinics might be more prone to revise patients, and could have a different fixation choice for the primary ALCR than surgeons in low-volume clinics. These surgeons could also attract more high-level athletes with a higher risk of re-injury. We have no complete data on the surgeons’ experience, the postoperative rehabilitation protocol, graft size, activity level of the patient, if TT or AM technique was used for femoral drilling, or if the hamstring tendons are semitendinosus grafts or a combination of semitendinosus and gracilis, which are factors that potentially could influence the risk of revision.

The use of revision surgery as the endpoint is a robust outcome measure, but it does not include patients with subjective or objective graft failures that have not undergone revision surgery. Although the number of graft failures is probably greater than the number of patients reaching our endpoint, we believe the observed differences are valid. In addition, we have no reason to believe that patients in certain fixation groups would be more prone to seek clinical attention and be considered for revision surgery. We do not have the data on why the patients were revised, which could potentially differ between fixation groups.

We have no data on death or emigration, which potentially could bias our results as a competing risk to revision. With a mean age of 28 years in the population, occurrence of death in the follow-up is likely to be low. We do not believe that occurrence of emigration would differ between the groups. Further, we do not have data on possible bilateral observations included. Even though the occurrence is probably not different amongst the groups investigated, this might have biased our results.

Summary

Although that the cause of revision ACLR is often multifactorial, the results from this study suggest that there could be substantial differences in revision risk dependent on what fixation method is used in hamstring autograft ACL reconstructions.The results illustrate the need for continuous multiregister cooperation with fixation devices registered by catalogue number to allow for early detection of possible implant failures.

All authors contributed to the planning of the project, interpreting results, draft revision, and approval of the manuscript. AP, TG, and BE did the statistical analysis.

The authors would like to thank all colleagues for reporting primary ACLRs and revisions to the registries. Special thanks are extended to the staff of the registries for data processing and quality assurance.

Acta thanks Brian Devitt and Jos van Raaij for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Aga C, Rasmussen M T, Smith S D, Jansson K S, LaPrade R F, Engebretsen L, Wijdicks C A.. Biomechanical comparison of interference screws and combination screw and sheath devices for soft tissue anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction on the tibial side. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41 (4): 841–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlden M, Samuelsson K, Sernert N, Forssblad M, Karlsson J, Kartus J.. The Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register: A report on baseline variables and outcomes of surgery for almost 18,000 patients. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40 (10): 2230–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad C S, Gardner T R, Groh M, Arnouk J, Levine W N.. Mechanical properties of soft tissue femoral fixation devices for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2004; 32 (3): 635–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andernord D, Bjornsson H, Petzold M, Eriksson B I, Forssblad M, Karlsson J, Samuelsson K.. Surgical predictors of early revision surgery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Results from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Register on 13,102 patients. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42 (7): 1574–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M J 2nd, Cordasco F A, Hannafin J A, Rodeo S A, O’Brien S J, Altchek D W, Cavanaugh J, Wickiewicz T L, Warren R F.. Results of revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Am J Sports Med 2007; 35 (12): 2057–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson K, Hartz A J.. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials. N Engl J Med 2000; 342 (25): 1878–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning W M 3rd, Kluczynski M A, Curatolo C, Marzo J M.. Suspensory versus aperture fixation of a quadrupled hamstring tendon autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2017; 45 (10): 2418–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuano L, Hardy P, Longo U G, Denaro V, Maffulli N.. No difference in clinical results between femoral transfixation and bio-interference screw fixation in hamstring tendon ACL reconstruction: A preliminary study. Knee 2008; 15 (3): 174–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drogset J O, Grontvedt T, Tegnander A.. Endoscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts fixed with bioabsorbable or metal interference screws: A prospective randomized study of the clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med 2005; 33 (8): 1160–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drogset J O, Straume L G, Bjorkmo I, Myhr G.. A prospective randomized study of ACL-reconstructions using bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts fixed with bioabsorbable or metal interference screws. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011; 19 (5): 753–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch S, Rittstieg A, Balcarek P, Walde T A, Schuttrumpf J P, Wachowski M M, Sturmer K M, Frosch K H.. Bioabsorbable interference screw versus bioabsorbable cross pins: Influence of femoral graft fixation on the clinical outcome after ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20 (11): 2251–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifstad T, Drogset J O, Grontvedt T, Hortemo G S.. Femoral fixation of hamstring tendon grafts in ACL reconstructions: The 2-year follow-up results of a prospective randomized controlled study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22 (9): 2153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granan L P, Bahr R, Steindal K, Furnes O, Engebretsen L.. Development of a national cruciate ligament surgery registry: The Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Am J Sports Med 2008; 36 (2): 308–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granan L P, Forssblad M, Lind M, Engebretsen L.. The Scandinavian ACL registries 2004–2007: Baseline epidemiology. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (5): 563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granan L P, Inacio M C, Maletis G B, Funahashi T T, Engebretsen L.. Intraoperative findings and procedures in culturally and geographically different patient and surgeon populations: An anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction registry comparison between Norway and the USA. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (6): 577–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi A, Ardern C L, Marcheggiani Muccioli G M, Neri M P, Marcacci M, Zaffagnini S.. Does revision ACL reconstruction measure up to primary surgery? A meta-analysis comparing patient-reported and clinician-reported outcomes, and radiographic results. Br J Sports Med 2016; 50 (12): 716–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harilainen A, Sandelin J.. A prospective comparison of 3 hamstring ACL fixation devices—Rigidfix, BioScrew, and Intrafix—randomized into 4 groups with 2 years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2009; 37 (4): 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoher J, Moller H D, Fu F H.. Bone tunnel enlargement after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Fact or fiction? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1998; 6 (4): 231–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S A, Abdul Ghafar S, Marwan Y, Mahgoub A M, Al Misfer A, Farouk H, Wagdy M, Alherran H, Khirait S.. Intratunnel versus extratunnel autologous hamstring double-bundle graft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A comparison of 2 femoral fixation procedures. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43 (1): 161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laxdal G, Kartus J, Eriksson B I, Faxen E, Sernert N, Karlsson J.. Biodegradable and metallic interference screws in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery using hamstring tendon grafts: Prospective randomized study of radiographic results and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med 2006; 34 (10): 1574–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Sun M, Ma C, Chen Y, Xue X, Guo P, Shi Z, Yan S. Clinical outcomes of transtibial versus anteromedial drilling techniques to prepare the femoral tunnel during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maletis G B, Granan L P, Inacio M C, Funahashi T T, Engebretsen L.. Comparison of community-based ACL reconstruction registries in the US and Norway. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(Suppl3): 31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano G, Mulas P D, Ziranu F, Piras S, Manunta A, Fabbriciani C.. Comparison between different femoral fixation devices for ACL reconstruction with doubled hamstring tendon graft: A biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy 2006; 22 (6): 660–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisala A S, Jarvela T, Paakkala A, Paakkala T, Kannus P, Jarvinen M.. Comparison of the bioabsorbable and metal screw fixation after ACL reconstruction with a hamstring autograft in MRI and clinical outcome: A prospective randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008; 16 (12): 1080–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers P, Logan M, Stokes A, Boyd K, Watts M.. Bioabsorbable versus titanium interference screws with hamstring autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy 2008; 24 (7): 817–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor C D, Guyatt G H.. Users’ guides to the medical literature, X: How to use an article reporting variations in the outcomes of health services. The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 1996; 275 (7): 554–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson A, Kjellsen A B, Fjeldsgaard K, Engebretsen L, Espehaug B, Fevang J M.. Registry data highlight increased revision rates for endobutton/biosure HA in ACL reconstruction with hamstring tendon autograft: A nationwide cohort study from the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry, 2004–2013. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43 (9): 2182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahr-Wagner L, Lind M.. The Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Registry. Clin Epidemiol 2016; 8: 531–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahr-Wagner L, Thillemann T M, Lind M C, Pedersen A B.. Validation of 14,500 operated knees registered in the Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Register: Registration completeness and validity of key variables. Clin Epidemiol 2013a; 5: 219–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahr-Wagner L, Thillemann T M, Pedersen A B, Lind M C.. Increased risk of revision after anteromedial compared with transtibial drilling of the femoral tunnel during primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Results from the Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Register. Arthroscopy 2013b; 29 (1): 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose T, Hepp P, Venus J, Stockmar C, Josten C, Lill H.. Prospective randomized clinical comparison of femoral transfixation versus bioscrew fixation in hamstring tendon ACL reconstruction: A preliminary report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2006; 14 (8): 730–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scannell B P, Loeffler B J, Hoenig M, Peindl R D, D’Alessandro D F, Connor P M, Fleischli J E.. Biomechanical comparison of hamstring tendon fixation devices for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, Part 2: Four tibial devices. Am J Orthop 2015; 44 (2): 82–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- To J T, Howell S M, Hull M L.. Contributions of femoral fixation methods to the stiffness of anterior cruciate ligament replacements at implantation. Arthroscopy 1999; 15 (4): 379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- www.aclregister.nu. Swedish ACL Register. Annual Report 2014.

- Ytterstad K, Granan L P, Ytterstad B, Steindal K, Fjeldsgaard K A, Furnes O, Engebretsen L.. Registration rate in the Norwegian Cruciate Ligament Register: Large-volume hospitals perform better. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (2): 174–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]