Abstract

Background and purpose

The best treatment option for severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is still controversial. We compared clinical and radiographic outcomes of modified Dunn procedure (D) and in situ fixation (S) in severe SCFE.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively compared D and S, used for severe stable SCFE (posterior sloping angle (PSA) > 50°) in 29 patients (15 D; 14 S). Propensity analysis and inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) to adjust for baseline differences were performed. Patients were followed for 2–7 years.

Results

Avascular necrosis (AVN) occurred in 3 patients out of 15, after D, causing conversion to total hip replacement (THR) in 2 cases. In S, 1 hip developed chondrolysis, requiring THR 3 years after surgery. 3 symptomatic femoroacetabular impingements (FAI) occurred after S, requiring corrective osteotomy in 1 hip, and osteochondroplasty in another case. The risk of early re-operation was similar between the groups. The slippage was corrected more accurately and reliably by D. The Nonarthritic Hip Score was similar between groups, after adjusting for preoperative and postoperative variables.

Interpretation

Although D was superior to S in restoring the proximal femoral anatomy, without increasing the risk of early re-operation, some concern remains regarding the potential risk of AVN in group D.

The slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) generally requires surgical management to stabilize the epiphysis, achieving early fusion of the proximal femoral physis and avoiding further displacement and deformity.

In situ screw fixation (S) remains the most common treatment for stable SCFE, regardless of the degree of deformity (Loder et al. 2012). Nonetheless, severe SCFE may lead to functional impairment, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), and progression to osteoarthritis (Ganz et al. 2003). Although the optimal treatment of these cases remains controversial, some authors agree that a severe displacement should be corrected during the same operation (Ziebarth et al. 2009, Novais et al. 2015, Sikora-Klak et al. 2017, Trisolino et al. 2017).

In recent years, the modified Dunn procedure (D) by means of surgical hip dislocation (Leunig et al. 2007, Ziebarth et al. 2009) has gained in popularity. The technique stabilizes the epiphysis and corrects the deformity in a single intervention, by restoring the femoral head–neck anatomy, possibly avoiding FAI sequelae. Furthermore, in experienced hands, D is safe, with low complication rates (Leunig et al. 2007, Ziebarth et al. 2009, 2013, Slongo et al. 2010, Skin et al. 2011, Novais et al. 2015). Nonetheless, some authors report increased rates of avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head and major complications, requiring revision surgery and total hip replacement (THR) in the short follow-up (Alves et al. 2012, Sankar et al. 2013, Souder et al. 2014, Javier et al. 2017, Sikora-Klak et al. 2017).

We compared the clinical and radiographic outcomes of D and S in severe stable SCFE.

Patients and methods

Study design

We retrospectively studied prospectively gathered data, comparing D and S in severe stable SCFE. The D was introduced in 2011 in our center; the learning curve of a senior surgeon (a well-trained hip specialist, who habitually performs approximately 300 hip operations per year) was supervised by 2 surgeons, highly experienced in D, who also participated in the majority of the operations. A local registry, with continuous data on patients affected by SCFE, was created and implemented. Our center is a tertiary referral hospital for pediatric orthopedics and traumatology, treating 15 to 25 new cases of SCFE per year.

Eligibility

Patients with severe stable SCFE (posterior sloping angle (PSA) > 50°), undergoing D, were included in the study. During the same period a cohort of patients undergoing S to address severe SCFE, according to surgeons’ preference and experience, was also included into the study. Because the surgeons took turns on duty, the choice of procedure depended on the available surgeon and his/her personal preference, thus the patients were not randomized.

We excluded mild to moderate SCFE (PSA <50°) and unstable SCFE, based on Loder’s criteria (Loder et al. 1993). We also excluded cases treated by different techniques such as closed reduction and internal fixation (CRIF) or intertrochanteric osteotomy (ITO) (Figure 1). No cases with associated comorbidities were identified in this series (for clinical data on all patients, see Table 1, Supplementary data).

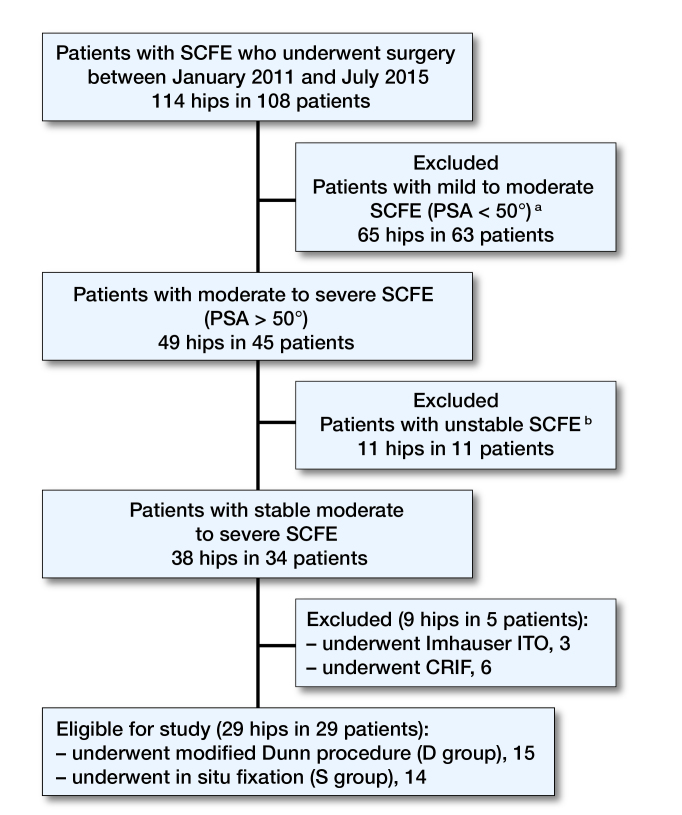

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of eligibility criteria. SCFE = slipped capital femoral epiphysis. PSA = posterior sloping angle. ITO = inter-trochanteric osteotomy. CRIF = closed reduction and internal fixation. a All cases with mild to moderate SCFE underwent S. b 8 patients were treated with CRIF, 1 patient with D, 2 patients with S.

From January 2011 to July 2015, 108 patients (114 hips) affected by SCFE were admitted to our department. Among them 29 hips in 29 patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. 15 patients (15 hips) underwent D and 14 patients (14 hips) underwent S (Table 2). The mean follow-up was 4.3 (range 2–6.5) years.

Table 2.

Patients’ demographic and preoperative data

| Clinical parameters | D group | S group | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female, n | 11/4 | 11/3 | 1.0 |

| Side L/R, n | 7/8 | 10/4 | 0.2 |

| Age at surgery (years) (SD) | 13.9 (2.3) | 13.0 (1.0) | 0.4 |

| Time elapsed from initial symptoms (months) | 12 (9) | 6 (5) | 0.05 |

| BMI (SD) | 24 (4) | 24 (4) | 0.9 |

| BMI-for-age (percentile) | 81 (21) | 82 (23) | 0.9 |

| Preoperative PSA (SD; °) | 68 (11) | 62 (9) | 0.2 |

| Follow-up (SD) | 3.7 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) | < 0.01 |

BMI = body mass index.

BMI-for-age percentiles were calculated according to the World Health Organization charts and tables (www.who.int/growthref/who2007)

PSA = posterior sloping angle.

Surgical technique

Modified Dunn procedure

The modified Dunn procedure was performed according to the previously described technique (Leunig et al. 2007, Ziebarth et al. 2009). Postoperatively, patients follow a non-weight-bearing protocol for 6 weeks followed by protected weight-bearing with crutches for 6 more weeks.

In situ fixation

Via an anterolateral skin incision a guidewire was introduced, under fluoroscopic guidance, in the anterior aspect of the femoral neck aiming toward the center of the femoral head in the AP and lateral projections. 2 4.5 mm fully threaded screws were placed, transfixing the femoral physis. Patients were allowed partial weight-bearing with crutches for 6 weeks.

Follow-up

Patients were followed for a median 4 (2–7) years. The Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) was used to assess clinical and functional outcomes of patients at the latest follow-up (Christensen et al. 2003). The PSA and the alpha angle on a frog-lateral view of the hip were used to assess the degree of correction and the radiographic presence of residual FAI deformity in the 2 groups.

Statistics

Continuous data were expressed as mean (SD), whereas categorical and ordinal data were expressed as proportions and 95% confidence interval (CI). Normality was tested using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for continuous variables. Differences in baseline and outcome characteristics between D and S were tested using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Student’s t-test (normal data distribution) or the Mann–Whitney U-test (skewed data distribution) for continuous variables. Exploratory univariable and multivariable analyses with Cox regression and general linear models were performed to assess the impact of the different treatments on the final outcomes. Results were presented as crude and adjusted relative risk (RR), for the dichotomous outcome variables and crude and adjusted mean for the continuous outcome variables; CI were reported for both.

To account for potential selection biases between the two groups, a propensity analysis was performed (Pirracchio et al. 2012). For each patient, we estimated propensity scores (PS) for receiving D or S, using a binary logistic model that included baseline variables (body mass index (BMI)-for-age percentile, according to the World Health Organization charts and tables; see www.who.int/growthref/who2007), time elapsed from initial symptoms and preoperative PSA). We included in the PS model only baseline variables hypothetically related to the outcome. The balance of the PS was checked observing the overlap in the range of propensity scores across the two treatments and comparing the quintiles (Garrido et al. 2014). 1 extreme case not overlapping in the common support (minima and maxima comparison) was excluded from the adjusted analysis. T-test showed no statistically significant differences in covariate means between the 2 treatment groups after matching.

Examining treatment effects on the outcome across PS quintiles, we did not observe any association between the outcome and the probability of receiving either treatment, which means that there is no evidence of unmeasured bias (Brookhart et al. 2013). Propensity scores were then used to derive inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW), with the inverse of the propensity score for patients with D and the inverse of 1 minus the propensity score for patients with S. Then, the IPTW was used to adjust the RR for early revision surgery in the two groups. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, and all reported p-values are 2-sided. We used Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS (version 22.0; IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis.

Ethics, funding, and potential conflicts of interest

The study was authorized by the local Ethical Committee. The data for this investigation were collected and analyzed in compliance with the procedures and policies set forth by the Helsinki Declaration, and all patients gave their informed consent to data treatment. No competing interests declared.

Results

No statistically significant differences were found between groups regarding sex distribution, age at presentation, BMI and BMI-for-age percentile, time elapsed from initial symptoms, and preoperative PSA.

The mean follow-up was shorter in D (3.7 (2–5.3) years) compared with S (4.9 (2.9–6.5) years), since the D was increasingly practiced in the latest years. The follow-up duration was considered as an independent covariate in regression analysis, as the difference between groups could influence the outcomes.

In D, 3/15 patients (20%; CI 5–49) developed AVN, 3 to 6 months after surgery. 2 of them underwent THR, 1.4 and 1.8 years after D respectively, while another patient was scheduled for the same procedure at the latest follow-up visit. 1 patient developed mild asymptomatic heterotopic ossifications. No patients in the S group developed AVN

In S, 1 case (7%; CI 4–36) developed chondrolysis 3 months after surgery, with severe pain, stiffness, and limping that did not regress at 3 years’ follow-up; the patient finally underwent THR elsewhere, 3 years after S. 3 other cases (21%; CI 6–51) developed symptomatic FAI with pain, stiffness, poor range of motion, and limping: one patient underwent sub-capital osteotomy by mean of surgical dislocation 1.2 year after S; the patient further developed septic nonunion, requiring THR 3 years after S. Another patient underwent femoral osteochondroplasty and labral repair 2.9 years after S. Finally, 1 patient was scheduled for corrective osteotomy but refused the operation at the latest follow-up visit.

The overall rate of re-operation was 17% (13% (CI 4–38) in D; 21% (CI 6–51) in S). The risk of early re-operation was similar in both groups.

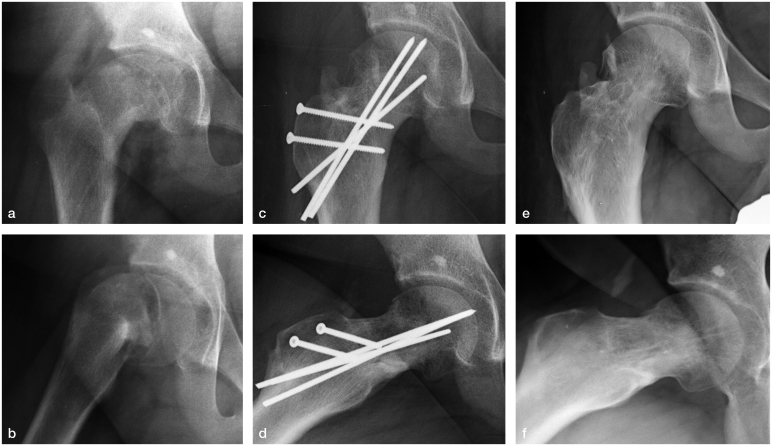

The slippage was corrected more accurately and reliably by D (Figure 2). The mean lateral alpha angle (50° (15) versus 89° (13); p-value <0.0001) and the median PSA (9° (8) versus 38° (20); p-value <0.0001) were lower in the D group compared with the S group (Table 3, see Supplementary data). The mean difference remained statistically significant after adjustment for IPTW and follow-up duration.

Figure 2.

Case no. 4. Severe stable SCFE in a 14-year-old boy treated by modified Dunn procedure: a–b: preoperative radiographs; c–d: postoperative radiographs; e–f: 3 years’ follow-up after hardware removal. Mild heterotopic ossification can be observed at the latest follow-up.

The Nonarthritic Hip Score (NAHS) was similar between groups at the latest follow-up, even after adjusting for IPTW and follow-up duration (Table 4, see Supplementary data), No interactions between NAHS (total and subscales) and preoperative or postoperative variables were found (all p-values for interaction tests >0.05). 11 patients were able to return to a low to moderate impact sport activity (bicycling, swimming, aerobics, running), while 8 patients could return to high-impact non-professional sport activity (soccer); there was a similar distribution between groups.

Discussion

We describe our initial experience with the modified Dunn procedure (D), comparing this technique with in situ fixation (S), which is the traditional treatment for stable SCFE.

A first issue is the lack of a clear indication for subcapital realignment among the different types and grades of SCFE. Some authors encourage the use of this procedure in unstable SCFE, due to a substantial decrease of AVN (Leunig et al. 2007, Slongo et al. 2010, Sankar et al. 2013, Ziebarth et al. 2013), while other authors warn about a doubled risk of AVN following D in unstable hips (Alves et al. 2012). Some authors advocate the use of D only in cases of severe SCFE (Madan et al. 2013, Novais et al. 2015), because of the general favorable prognosis of S in mild SCFE, while other authors suggest D also in cases of mild SCFE, to avoid FAI-induced chondrolabral damage (Ziebarth et al. 2013). Thus an evidence-based algorithm of treatment is still lacking.

We started our experience treating cases of severe stable SCFE. We hypothesized that the potential risk of AVN could be balanced by the expected benefit of a substantial reduction of the residual impingement. To test our hypothesis, we matched cases of D with cases of S. S is the most widely accepted treatment for SCFE at any grade of severity: the technical ease, the low risk of complications, and the potential role of bone remodeling, with spontaneous improvement of the deformity, confirmed this technique as the gold standard of SCFE treatment for years (Loder et al. 2012).

As expected, the most frequent complication we encountered in the D group was AVN, which occurred in 3/15 hips but in none of 14 hips operated with S. With the small numbers available, the difference was not statistically significant, but is still a concern. The issue of the learning curve in D has been highlighted in other studies. Upasani et al. (2014) reported an important association between the surgeon’s volume and experience in performing D and the likelihood of major complications. In our series the rate of AVN was consistent with previous reports of surgeons at the beginning of the learning curve (Alves et al. 2012, Sankar et al. 2013, Souder et al. 2014, Upasani et al. 2014, Javier et al. 2017, Sikora-Klak et al. 2017), confirming that D is technically demanding. Conversely, in a previous report, we excluded a substantial impact of surgeon’s volume and experience in Imhauser ITOs, as 16 different surgeons performed 53 procedures across the years (Trisolino et al. 2017).

The most important difference between the 2 procedures is the restoration of the head–neck anatomy, provided by D. We observed better radiographic outcomes in D. Whether or not some remodeling was observed also after S, this effect was inconstant and incomplete, leaving an important deformity in the majority of cases, causing symptomatic FAI in 3/14 patients, leading to early re-operation or THR.

FAI has been associated with increased pain, reduced ROM, chondrolabral damage, and early hip osteoarthritis (Ganz et al. 2008, Agricola et al. 2013, Castaneda et al. 2013). Also, the residual deformity in SCFE has been associated with early chondrolabral damage (Lee et al. 2013, Klit et al. 2014, Wylie et al. 2015). FAI following the surgical treatment of SCFE often requires early revision surgery, even THR, similarly to AVN.

2 other retrospective non-matched studies compared D and S in the treatment of severe stable SCFE (Souder et al. 2014, Novais et al. 2015), while 1 retrospective study compared D with ITO (Sikora-Klak et al. 2017). Souder et al. (2014) compared 64 stable SCFE treated by S and 10 stable SCFE treated by D and reported 2 cases of AVN in D and no cases in S. The authors concluded that stable SCFE should be better treated with S to minimize the risk of AVN, postponing the correction of the deformity, if need be.

Conversely, Novais et al. (2015) compared 15 severe stable SCFE, treated by D, with a historical series of 15 severe stable SCFE treated by S. They found a better radiographic correction after D and no substantial differences in rate of AVN between the two groups but an increased number of re-operations and worse clinical outcomes following S.

Recently Sikora-Klak et al. (2017) retrospectively compared 14 D and 12 Imhauser ITO, performed for high-grade stable SCFE. They found 3/14 AVN in the D group, but no difference in the rate of complications and a slightly higher rate of re-operations following ITOs. In their experience, ITO allowed acceptable correction of the deformity, compared with D.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective design and lack of randomization introduced potential selection biases. In particular, the follow-up duration (> 1 year shorter in the D group) may underestimate the rate of re-operation in D. Conversely the minimum follow-up of 2 years, adequate to estimate the incidence of some postoperative complications (AVN, nonunion, slip progression), could be insufficient to evaluate the effect of FAI on the onset of early osteoarthritis. An increase of re-operations and THR could be expected in S, because of the high rate of severe FAI (Agricola et al. 2013). The sample size is underpowered to evaluate, for example, the differences in AVN incidence. Finally, the absence of MRI confirmation of the femoral head vitality does not allow any definitive conclusion to be drawn regarding the onset of AVN as a complication of the treatment rather than the disease. Nevertheless, based on our results, we can affirm that D is superior to S in restoring the proximal femoral anatomy, without increasing the rate of revision surgery at short-term follow-up. Additional studies are needed to assess the long-term effectiveness of D, and also in comparison with extra-articular osteotomies, which are technically easier, showing low rates of major complications and satisfactory long-term results (Trisolino et al. 2017).

Supplementary data

Tables 1, 3, and 4 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2018.1439238.

GT, SS and GP conceived and planned the project. GT carried out the implementation of the database, analyzed the data, performed the calculations, interpreted the results with critical feedback by all authors, and wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. GG and PL contributed to the data collection and database implementation, data analysis and calculations, and helped in writing and editing the manuscript.

We would like to thank Dr Elettra Pignottti for her valuable assistance in the statistical analysis.

Acta thanks Randall Loder and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- Agricola R, Heijboer M P, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, Verhaar J A, Weinans H, Waarsing J H.. Cam impingement causes osteoarthritis of the hip: A nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK) Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72 (6): 918–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves C, Steele M, Narayanan U, Howard A, Alman B, Wright J G.. Open reduction and internal fixation of unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis by means of surgical dislocation does not decrease the rate of avascular necrosis: A preliminary study. J Child Orthop 2012; 6 (4): 277–83. doi: 10.1007/s11832-012-0423-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookhart M A, Wyss R, Layton J B, Stürmer T, Propensity score methods for confounding control in nonexperimental research. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6 (5): 604–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda P, Ponce C, Villareal G, Vidal C.. The natural history of osteoarthritis after a slipped capital femoral epiphysis/the pistol grip deformity. J Pediatr Orthop 2013; 33 (Suppl 1): S76–S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen C P, Althausen P L, Mittleman M A, Lee J A, McCarthy J C.. The nonarthritic hip score: Reliable and validated. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (406): 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn D M. The treatment of adolescent slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1964; 46: 621–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leuning M, Notzli H, Siebenrock K A.. Femoroacetabular impingement: A cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; 417: 112–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Leunig M, Leunig-Ganz K, Harris W H.. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: An integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008; 466 (2): 264–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido M M, Kelley A S, Paris J, Roza K, Meier D E, Morrison R S, Aldridge M D.. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res 2014; 49 (5): 1701–20. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier M J, Victoria A, Martín D, Gabriela M, Claudio A F.. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with the modified Dunn procedure: A multicenter study. J Pediatr Orthop 2017; Jan 18. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klit J, Gosvig K, Magnussen E, Gelineck J, Kallemose T, Søballe K, Troelsen A.. Cam deformity and hip degeneration are common after fixation of a slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(6): 585–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C B, Matheney T, Yen Y M.. Case reports: acetabular damage after mild slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (7): 2163–72. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2715-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leunig M, Slongo T, Kleinschmidt M, Ganz R.. Subcapital correction osteotomy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis by means of surgical hip dislocation. Oper Orthop Traumatol 2007; 19: 389–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder R T, Richards B S, Shapiro P S, et al. . Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: The importance of physeal stability. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993; 75-A: 1134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder R T, Dietz F R.. What is the best evidence for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis? J Pediatr Orthop 2012; 32 (Suppl 2): S158–S65. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e318259f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan S S, Cooper A P, Davies A G, et al. . The treatment of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis via the Ganz surgical dislocation and anatomical reduction: A prospective study. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B: 424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novais E N, Hill M K, Carry P M, et al. . Modified Dunn procedure is superior to in situ pinning for short-term clinical and radiographic improvement in severe stable SCFE. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2015; 473: 2108–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirracchio R, Resche-Rigon M, Chevret S.. Evaluation of the propensity score methods for estimating marginal odds ratios in case of small sample size. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12: 70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankar W N, Vanderhave K L, Matheney T, Herrera-Soto J A, Karlen J W.. The modified Dunn procedure for unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis: A multicenter perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95: 585–91. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikora-Klak J, Bomar J D, Paik C N, Wenger D R, Upasani V.. Comparison of surgical outcomes between a triplane proximal femoral osteotomy and the modified Dunn procedure for stable, moderate to severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2017; Mar 10. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slongo T, Kakaty D, Krause F, et al. . Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a modified Dunn procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92 (18): 2898–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin E, Beaule P E, Sucato D, et al. . Multicenter study of complications following surgical dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93 (12): 1132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souder C D, Bomar J D, Wenger D R.. The role of capital realignment versus in situ stabilization for the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2014; 34 (8): 791–8. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trisolino G, Pagliazzi G, Di Gennaro G L, Stilli S.. Long-term results of combined epiphysiodesis and Imhauser intertrochanteric osteotomy in SCFE: A retrospective study on 53 hips. J Pediatr Orthop 2017; 37 (6): 409–15. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upasani V V, Matheney T H, Spencer S A, Kim Y J, Millis M B, Kasser J R.. Complications after modified Dunn osteotomy for the treatment of adolescent slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2014; 34 (7): 661–7. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie J D, Beckmann J T, Maak T G, Aoki S K.. Arthroscopic treatment of mild to moderate deformity after slipped capital femoral epiphysis: intra-operative findings and functional outcomes. Arthroscopy 2015; 31(2): 247–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebarth K, Zilkens C, Spencer S, Leunig M, Ganz R, Kim Y J.. Capital realignment for moderate and severe SCFE using a modified Dunn procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467 (3): 704–16. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0687-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebarth K, Leunig M, Slongo T, Kim Y J, Ganz R.. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: Relevant pathophysiological findings with open surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (7): 2156–62. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-2818-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebarth K, Milosevic M, Lerch T D, Steppacher S D, Slongo T, Siebenrock K A.. High survivorship and little osteoarthritis at 10-year follow-up in SCFE patients treated with a modified Dunn procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475 (4): 1212–28. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.