Summary

We report a single-centre, randomized study evaluating the efficacy and safety of concurrent fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone (FND) and rituximab versus sequential FND followed by rituximab in 158 patients with advanced stage, previously untreated indolent lymphoma, enrolled between 1997–2002. Patients were randomized to 6-8 cycles of FND followed by 6 monthly doses of rituximab or 6 doses of rituximab given concurrently with FND. All patients who achieved at least a partial response received 12 months of interferon (IFN) maintenance. Median ages were 54 and 55 years. The two groups were comparable with the exception of a higher percentage of females (65% vs. 43%) and baseline anaemia (23% vs. 11%) in the FND followed by rituximab group. Complete response/unconfirmed complete response rates were 89% and 93%. The most frequent grade ≥ 3 toxicity was neutropenia (86% vs, 96%). Neutropenic fever occurred in 21% and 16%. Late toxicity included myelodysplastic syndrome (n=3) and acute myeloid leukaemia (n=5). With 12.5 years of follow-up, no significant differences based on treatment schedule were observed. 10-year overall survival estimates were 76% and 73%. 10-year progression-free survival estimates were 52% and 51%. FND with concurrent or sequential rituximab, and IFN maintenance in indolent lymphoma demonstrated high response rates and robust survival.

Keywords: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chemotherapy, immunotherapy

Introduction

The indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are characterized as slow-growing B-cell malignancies with responsiveness to initial therapy, coupled with inevitable relapse following standard therapy. The majority of cases of indolent lymphoma include follicular (FL), small lymphocytic (SLL) and marginal zone lymphoma (MZL). No consensus has been reached on the preferred initial management strategy for indolent lymphoma, and treatment options are heterogeneous, varying from watchful waiting to intensive combination therapy (Friedberg et al., 2009). Some reports indicate superior results when more intensive anthracycline-containing regimens are used front-line (Federico et al., 2013, Nastoupil et al., 2014, McLaughlin, 2006), but this is a topic of ongoing controversy. The purine nucleoside analogues, especially fludarabine, demonstrated promising results in combination and as a single agent in indolent lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (McLaughlin et al., 1996a, McLaughlin et al., 1996b, Keating et al., 2005, Keating et al., 1989, Keating et al., 1993, Zinzani et al., 2004a, Zinzani et al., 2004b). In our experience, fludarabine, mitoxantrone and dexamethasone (FND) compared favourably to intensive alternating triple chemotherapy with high response rates that were durable, and was associated with a more favourable toxicity profile in untreated, stage IV indolent lymphoma (Tsimberidou et al., 2002).

Numerous investigators have observed improvements in long term outcomes with the incorporation of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies with various chemotherapy regimens in indolent lymphoma (Marcus et al., 2005, Hiddemann et al., 2005, Herold et al., 2007, Salles et al., 2008). This was not surprising as the use of immunotherapy for indolent lymphoma had been advocated for many years and several studies reported benefit with interferon (IFN) in combination with chemotherapy or rituximab (McLaughlin et al., 1993, Herold et al., 2007, Salles et al., 2008, Smalley et al., 1992, Solal-Celigny et al., 1993). The addition of rituximab to FND was hypothesized to be synergistic and result in higher molecular remission rates than chemotherapy alone, warranting further exploration with the combination of rituximab and FND when this study design was developed. The concern at the time was whether the concurrent use of rituximab would result in additive toxicity, to answer this question, two separate dosing schemas were examined. Therefore, we set out to compare the efficacy and safety of concurrent FND in combination with rituximab versus sequential FND followed by rituximab and one year of IFN maintenance in patients with previously untreated, advanced stage SLL, MZL or FL.

Methods

We performed a randomized, single-centre, open-label study. All patients provided written informed consent. The trial was approved by The University of Texas M.D. Anderson institutional review board and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice.

Eligible patients included those aged 18 to 76 years with previously untreated, stage IV FL, SLL or MZL and adequate hepatic (bilirubin < 1.5 × upper limit of normal [ULN]), cardiac (left ventricular ejection fraction ≥ 50%) and renal function (creatinine < 1.5 × ULN). Patients were considered ineligible if they had an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of <1.0 x109/l, or platelet count < 100 x109/l unless the direct result of marrow infiltration by lymphoma. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, antecedent malignancy with < 90% probability of surviving five years, patients unwilling to accept blood products, or those who were pregnant or lactating were excluded.

Study Design

The primary endpoint of the study was to determine the efficacy of concurrent rituximab in combination with FND followed by IFN in comparison to FND followed by rituximab and IFN in patients with stage IV indolent lymphoma as measured by complete response (CR) rate. Secondary endpoints included comparison of safety and tolerability, molecular response, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Patients were stratified based on tumour mass size (< 5 cm vs. ≥ 5 cm); age (< 60 vs. ≥ 60 years); histology, and suitability for watch and wait approach.

Treatment

Patients were randomly assigned either to fludarabine 25 mg/m2 on days 1-3, mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2 on day 1, and dexamethasone 20mg on days 1-5 every 28 days for a total of 6-8 cycles followed by six monthly doses of rituximab, 375 mg/m2 (initiated 12 months after randomization) or to the experimental arm of concurrent rituximab 375 mg/m2 administered on days 1 and 8 of cycle 1, then on day 1 of cycles 2-5 with fludarabine 25 mg/m2 on days 2-4, mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2 on day 2, and dexamethasone 20 mg on days 1-5. Pre-medication with 650 mg of acetaminophen and 25-50 mg of diphenhydramine were administered prior to each infusion of rituximab. Eight cycles of FND were planned in both arms unless cumulative myelosuppression was encountered (> 6 weeks for recovery of ANC to ≥ 1.0 x109/l or platelet count to > 100 x109/l), in which case FND was completed after 6 cycles as tolerated. Subjects experiencing delayed recovery of ANC (>35 days) or neutropenic fever were candidates for granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) in addition to chemotherapy dose adjustment. All subjects received pneumocystis prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfa or pentamidine.

All subjects who achieved at least a partial response (PR) after completion of FND ± rituximab received IFN alfa-2b maintenance, 3 million units/m2 starting one month after FND on days 1-14 every month for 12 cycles. For subjects in the control arm receiving rituximab and IFN in the same month, rituximab was administered on day 1 and IFN on days 2-15. Response was assessed by the investigator in accordance with the International Workshop on Standardized Response Criteria for NHL (Cheson et al., 1999). A molecular CR was defined as a patient with an initially positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) who converted to negative on at least 2 consecutive occasions no less than 2 months apart. A CR was defined as those with no clinical and radiographic evidence of disease. All lymph nodes and nodal masses must have regressed to normal size (≤ 1.5 cm in their greatest transverse diameter for nodes > 1.5 cm before therapy). Previously involved nodes that were 1.1 to 1.5 cm in their greatest transverse diameter before treatment must have decreased to ≤ 1 cm in their greatest transverse diameter after treatment. CR unconfirmed (CRu) was defined as regression of nodal masses by more than 75% in the sum of the products of the greatest diameters (SPD) and or all nodal masses regressed to normal size with an indeterminate bone marrow (Cheson et al., 1999). Response assessment occurred every three cycles during therapy. Off therapy response assessment occurred every six months for the first five years, and then annually thereafter. PCR for BCL2 in the peripheral blood and bone marrow was assessed every six months during the first three years.

Statistical Methods

Efficacy endpoints were analysed in the intent-to-treat population. A target sample size of 128 subjects (64 subjects in each arm) was calculated based on the anticipated molecular response rates of 85% to detect a difference of 25% in the 12-month molecular CR rates, this assumed a two-sided α level of 0.05 and 90% power. An amendment in May of 2001 increased the planned accrual to include additional subjects with FL as a result of a higher than expected number of subjects with SLL and MZL enrolled to fulfil the primary endpoint.

The Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test was used to evaluate the association between categorical variables. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to evaluate the difference in a continuous variable between patient groups. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for time-to-event analysis including PFS, time to second malignancy, disease-specific survival and OS. Median time to event in years with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated. The Log-rank test was used to evaluate the difference in time-to-event endpoints between patient groups. Univariate Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to evaluate the effects of continuous variables on time-to-event outcomes. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used for multivariate analysis to include important and significant covariates. Statistical software SAS 9.1.3 (SAS, Cary, NC) and S-Plus 8.0 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA) were used for all the analyses. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

A total of 158 patients were recruited between 1997–2002 at our single centre. Table I lists baseline characteristics by treatment arm. Median age was 54 (range 20 to 76) years; 29% of patients were older than 60 years of age. One hundred and eleven (70%) patients had FL, 18 (12%) had MZL and 29 (18%) had SLL; 91% of subjects had bone marrow involvement. Seventy-eight subjects were randomized to the FND followed by rituximab arm and 80 subjects were randomized to the concurrent rituximab and FND arm. There were significantly more female patients (65% vs. 43%, P=0.004) and a higher percentage of patients with haemoglobin <120 g/l (23% vs. 11%, P=0.048) in the FND followed by rituximab arm. The distributions of Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score between the treatment arms were similar (P=0.63).

Table I.

Baseline Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Patients, n (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | FND→R N = 78 |

RFND N = 80 |

| Age, years; median range | 54 24-76 |

55 20-76 |

| Sex, female | 51 (65) | 34 (43) |

| Diagnosis | ||

| FL | 56 (72) | 55 (69) |

| MZL | 6 (8) | 12 (15) |

| SLL | 16 (20) | 13 (16) |

| B symptoms, yes | 7 (9) | 11 (14) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 72 (92) | 71 (89) |

| FLIPI Score, | ||

| low (0-1) | 15 (19) | 17 (21) |

| intermediate (2) | 34 (44) | 39 (49) |

| high (≥ 3) | 29 (37) | 24 (30) |

| Low tumour burden | 23 (30) | 25 (31) |

| Bulky cut-off? | 4 (5) | 7 (9) |

FL, follicular lymphoma; FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index; FND→R, sequential fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone followed by rituximab; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; RFND, concurrent fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone and rituximab; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma.

Efficacy

The best overall response rate was 99%, 143 (91%) subjects achieved a CR (n=128) or CRu (n=15) and 13 (8%) achieved a PR. There was no significant difference in CR by treatment group (89% vs. 93%, P=0.39). Prognostic factors associated with a lower CR rate included age >60 years, high FLIPI score, high tumour burden, elevated β-2 microglobulin and >4 nodal sites. A significantly higher percentage of subjects in the concurrent rituximab plus FND achieved a peripheral blood complete molecular response at six (89% vs. 60%, P=0.002) and 12 months (89% vs. 68%, P=0.04) in comparison to the FND followed by rituximab arm.

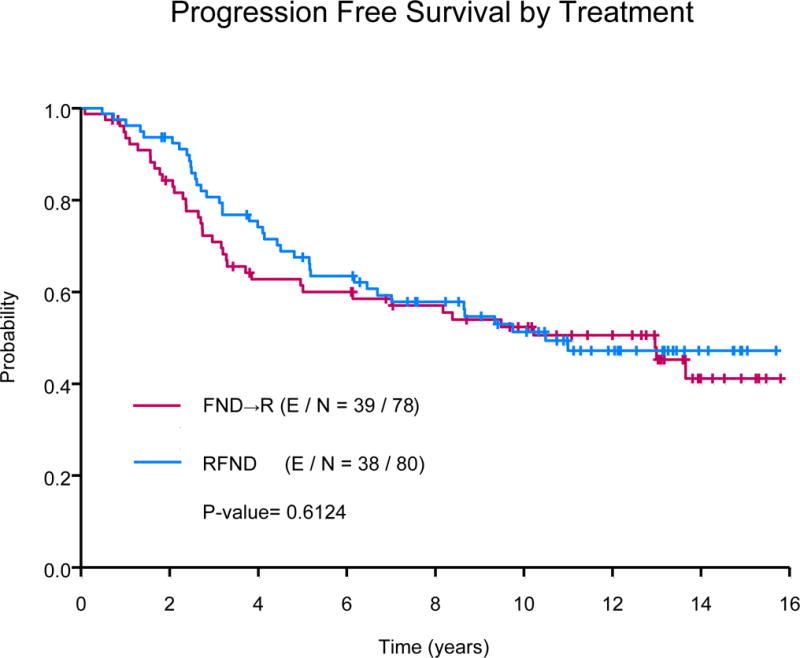

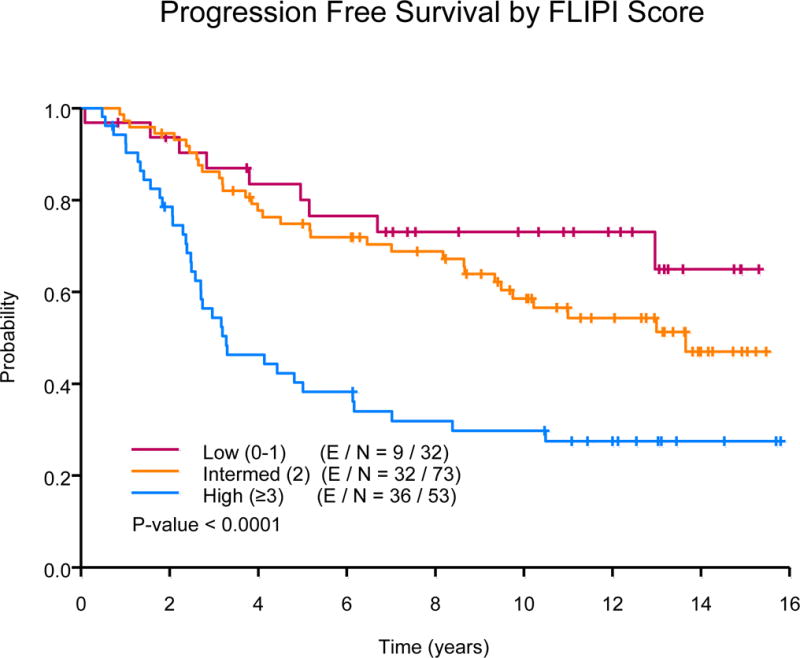

The median follow-up was 12.54 years (range: 3.43 -15.80) for the censored observations. The median PFS of all subjects was 11 years, 77 events were observed. Ten-year PFS estimates were 52% (95% CI, 42-65%) in the FND followed by rituximab arm versus 51% (95% CI, 41-64%) in the concurrent rituximab plus FND arm (P=0.61), Fig 1A. The 10-year PFS estimates were similar among those with low or high tumour burden (55% vs. 50%, P=0.28). In univariate analyses, median PFS was significantly longer among the low (not reached [NR]) or intermediate-risk FLIPI (13.7 years) group versus high-risk FLIPI (3.3 years, P=<0.0001), Fig 1B. In multivariate analysis adjusting for histology, FLIPI score and β-2 microglobulin, there was no difference in PFS based on treatment schedule (concurrent R+FND vs. FND followed by R hazard ratio [HR] = 1.15; 95% CI, 0.71-1.86).

Fig 1.

(A) Progression-free survival by treatment.

FND→R, sequential fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone followed by rituximab; RFND, concurrent fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone and rituximab.

(B) Progression-free survival by Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score

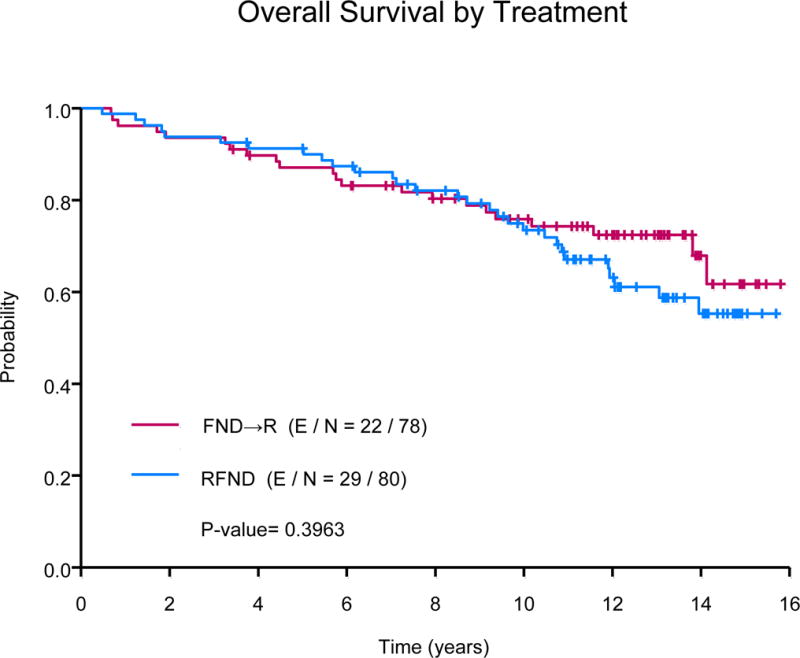

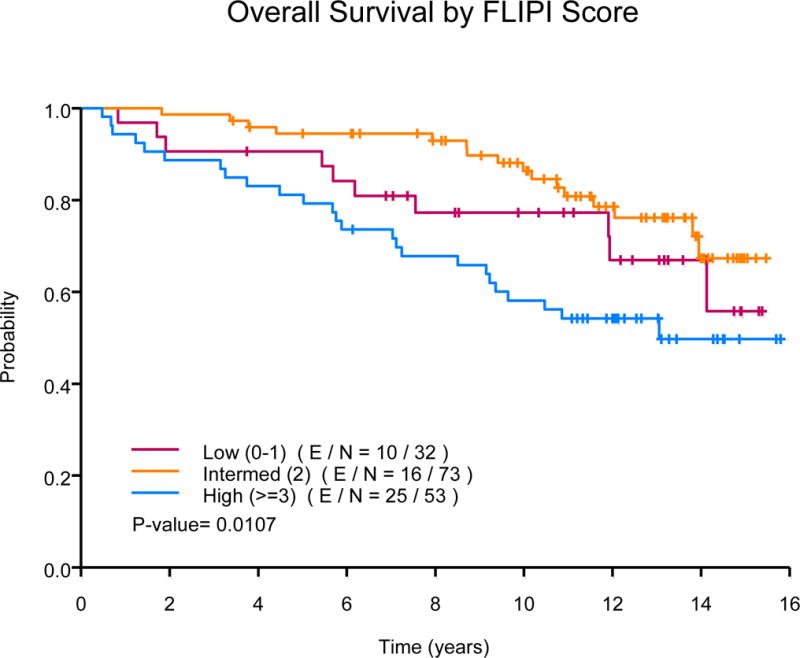

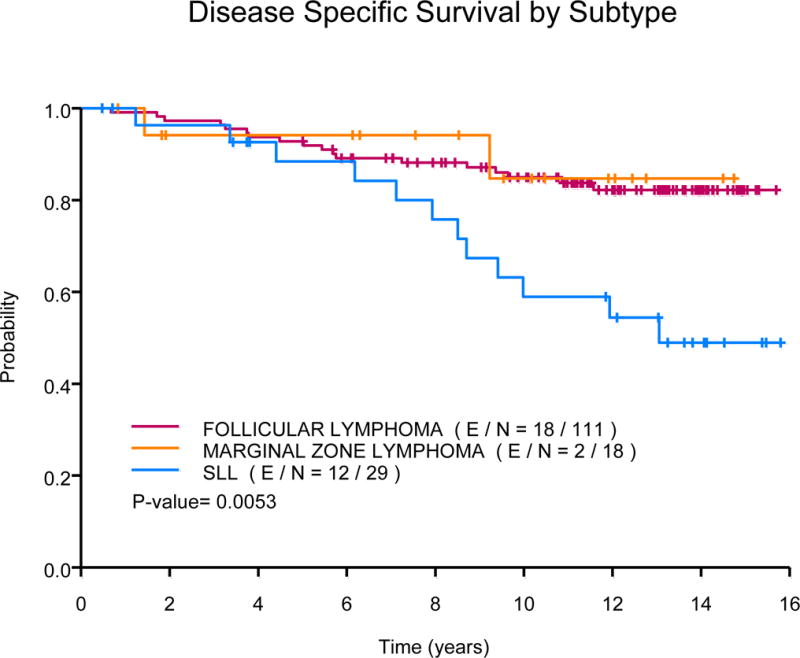

The median OS has not been reached. Fifty-one patients died during follow-up, 32 are deceased as a result of progressive lymphoma or late treatment-related complications, 10 died due to an unrelated condition (cardiovascular n=3; adenocarcinoma n=3, intracranial haemorrhage n=2; neuroendocrine tumour n=1; ileus n=1), and 9 of unknown cause. Ten-year OS estimates were 76% (95% CI, 67-86%) in the FND followed by rituximab arm versus 73% (95% CI, 64-84%) in the concurrent rituximab plus FND arm (P=0.4), Fig 2A. The median OS was significantly longer among low (NR) or intermediate-risk FLIPI (NR) group versus high-risk FLIPI (13.1 years, P=0.01), Fig 2B. The median OS was also significantly longer based on histology, NR for those with FL, 10.5 years for those with MZL and 13.1 years for those with SLL (P=0.0008). The 10-year OS estimates were similar among those with low or high tumour burden (78% vs. 73%, P=0.45). In multivariate analysis, there was no difference in OS based on treatment schedule (concurrent R+FND vs. FND followed by R HR=1.75; 95% CI, 0.94-3.26). The median disease-specific survival was NR for those with FL or MZL and 13.1 years for those with SLL (P=0.005). Ten-year disease-specific survival rates were 85% (95% CI, 78-92%) for FL, 85% (95% CI, 67-100%) for MZL and 59% (95% CI, 42-82%) for those with SLL, Fig 3A.

Fig 2.

(A) Overall survival by treatment

FND→R, sequential fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone followed by rituximab; RFND, concurrent fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone and rituximab.

(B) Overall survival by Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score

Fig 3.

(A) Disease-specific survival by subtype

SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma

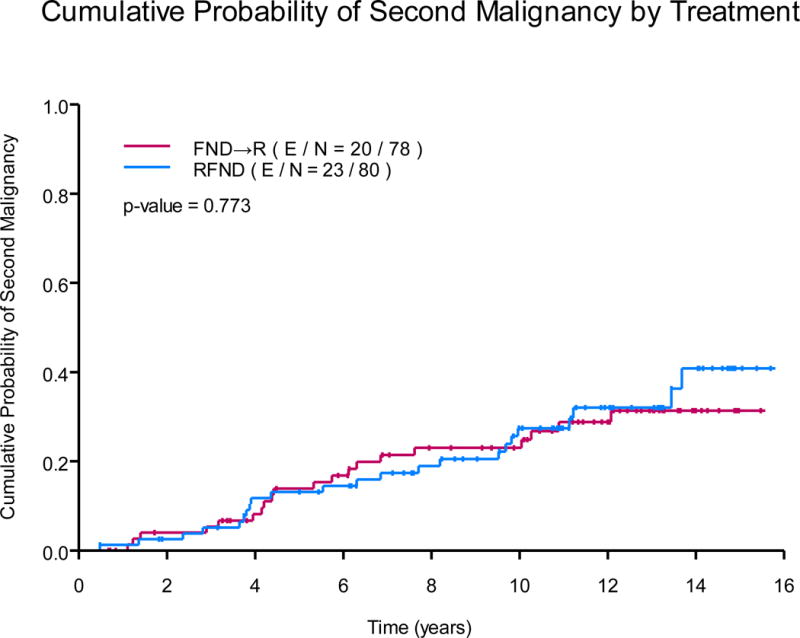

(B)Cumulative probability of second malignancy by treatment

FND→R, sequential fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone followed by rituximab; RFND, concurrent fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone and rituximab.

Safety and Tolerability

All of the 158 subjects received at least one cycle of treatment. Sixty-five per cent (n=102) completed 8 cycles of FND. Thirteen (n=21) per cent completed 6 cycles and 8% (n=12) completed 7 cycles. The remaining 14% discontinued therapy early because of intolerable toxicity. Sixty per cent (n=94) of subjects completed the planned IFN maintenance; 19% discontinued therapy early because of intolerable toxicity. Grade ≥3 haematological adverse events were frequent. There was a lower percentage of grade ≥3 neutropenia in the sequential group (FND followed by rituximab), 86% versus 96%. However, there was a higher percentage of neutropenic fever, 21% vs. 16%, in the sequential group. Grade ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia was 19% and 29%. Grade ≥ 3 anaemia was 13% and 14%, respectively.

The acute grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurring in more than approximately 5% of patients in either group are summarized in Table II. Grade ≥3 non-haematological adverse events were relatively infrequent, and included fatigue (19% and 15%), infection (10% and 16%), anxiety/depression (8% and 4%) and nausea/emesis (5% in each group). No acute adverse events resulted in treatment-related mortality.

Table II.

All Grade ≥3 Adverse Events

| Adverse Events by Grade, n (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FND→R N = 78 |

RFND N = 80 |

|||

| Toxicity* | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

|

|

|

|

||

| Non-haematological | ||||

| Anxiety/depression | 5 (6) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 1(1) |

| Fatigue | 13 (17) | 2 (3) | 10 (13) | 2 (3) |

| Neutropenic fever | 16 (21) | 0 | 13 (16) | 0 |

| Infection | 6 (8) | 2 (3) | 13 (16) | 0 |

| Nausea/emesis | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 0 |

| Haematological | ||||

| Neutropenia | 13 (17) | 54 (69) | 13 (16) | 64 (80) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 10 (13) | 5 (6) | 14 (18) | 9 (11) |

| Anaemia | 3 (4) | 7 (9) | 5 (6) | 6 (8) |

FND→R, sequential fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone followed by rituximab; RFND, concurrent fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone and rituximab

Second malignancies occurred in 43 (27%) subjects, summarized in Table III. Of these, 11 (7%) died as a result of their second malignancy. Five subjects are deceased as a result of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML, 3%), and the remaining were the result of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS, n=1), acute lymphocytic leukaemia (n=1), adenocarcinoma of unknown primary (n=2), gastric adenocarcinoma (n=1), or high grade neuroendocrine tumour (n=1). Age was an important prognostic factor for development of a second malignancy from univariate analysis (HR=1.06; 95% CI, 1.03-1.10). There was no difference in the observed second malignancy based on the treatment schedule from multivariate analysis (HR=1.17, 95% CI, 0.63-2.17), Fig 3B.

Table III.

Second Malignancy

| Malignancy | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | 5 (3) |

| Acute lymphocytic leukaemia | 1 (<1) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | 3 (2) |

| Breast | 4 (3) |

| Lung | 3 (2) |

| Prostate | 2 (1) |

| Renal | 1 (<1) |

| Urothelial | 1 (<1) |

| Gastric | 1 (<1) |

| Colon | 1 (<1) |

| Liver | 1 (<1) |

| Pancreas | 1 (<1) |

| Neuroendocrine | 1 (<1) |

| Melanoma | 1 (<1) |

| Non-melanoma skin cancer | 5 (3) |

| Cervical cancer | 1 (<1) |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 5 (3) |

| Other | 5 (3) |

Discussion

This randomized trial compared two different treatment schedules of rituximab in combination with FND followed by IFN maintenance in previously untreated, stage IV, indolent lymphoma. The results demonstrate that patients receiving rituximab concurrently with FND achieved a more rapid complete molecular response, outlined by negative PCR for BCL2 at six and 12 months in each respective treatment arm. However, there was no observed difference in the CR or CRu rate, which was high in this study population whether rituximab was administered sequentially or concurrently with chemotherapy. With mature follow-up, the initial high response rates were durable with favourable 10-year PFS and OS estimates that did not appear to be impacted by the schedule of rituximab.

The lack of statistical significance in our findings regarding the two treatment arms may be explained by the impact of the clinical benefit of rituximab, which appeared to be independent of the timing of administration. The rapid molecular response with the early incorporation of rituximab may have been mitigated by the high complete response rates and prolonged remission duration. With mature follow-up, our findings suggest that depth of response may predict duration of response. Similarly, other prospective studies examining a fludarabine-based frontline regimen in indolent lymphoma have demonstrated high complete response rates which translated into prolonged response duration (Montoto et al., 2008, Tomas et al., 2011, Vitolo et al., 2013, Zinzani et al., 2004b). A retrospective analysis of 536 patients with FL enrolled in the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Altude (GELA) GELF86 studies with 14.9 years of follow-up reported that achieving a CR with first-line therapy was associated with superior OS (Bachy et al., 2010). In addition, a collaboration of clinicians and statisticians with expertise in FL and/or surrogate endpoint assessment identified a durable complete response (CR at 30 months) as a novel surrogate endpoint for PFS in first-line FL studies (Sargent et al, 2015). With mature follow-up, our findings suggest that achieving a CR with first-line therapy is associated with high 10-year PFS and OS rates in advanced stage, indolent lymphoma.

Despite the high response rates, the tolerability of this schedule of 8 cycles of FND remains a concern. While non-haematological toxicity was very modest, 14% of subjects in this study were unable to complete the planned therapy, mainly because of marrow toxicity. Similar findings were observed in a prospective observational cohort of previously untreated FL patients receiving frontline chemoimmunotherapy, the majority of whom were treated in community-based practice (Nastoupil et al., 2015). Approximately 12% of subjects treated with rituximab in combination with fludarabine-based chemotherapy discontinued treatment early as a result of intolerable toxicity, which was significantly higher than those treated with rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP; 4%) or rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R-CVP; 8% (Nastoupil et al., 2015). With bendamustine and rituximab associated with a tolerable safety profile and a superior PFS in comparison to R-CHOP in previously untreated indolent lymphoma, (Rummel et al., 2013) the adoption of FND plus rituximab in this setting may be impacted by concerns about tolerability.

Abbreviated induction with fludarabine-based chemotherapy has been explored to improve tolerance or expand application to elderly or unfit patients (Vitolo et al., 2013, Zinzani et al., 2012). A randomized, multi-centre phase III study examined four cycles of R-FND followed by rituximab maintenance versus observation in 242 treatment-naïve patients aged 60–75 years of age (Vitolo et al., 2013). The ORR was 86% (55% CR/CRu) after induction. The most frequent grade 3 or 4 toxicity was neutropenia, 25% with 13 serious infections. A single arm, phase II trial including 55 patients reported an ORR of 96% (38 out of 55 achieved a CR) following four induction cycles of rituximab, fludarabine and mitoxantrone (R-FM), the study also included subsequent consolidation with 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan (90Y-IT) (Zinzani et al., 2012). The abbreviated R-FM induction was well tolerated with reversible haematological toxicity being the most common adverse events. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia was observed in 35%. Fewer cycles resulted in better tolerance with similar high CR and PFS rates, suggesting that one approach to reduce the toxicity associated with this regimen, but maintain efficacy would be to pursue four cycles of R-FND as induction.

We previously reported on the risk of treatment-related MDS/AML among patients from this study after a median follow-up of 42 months (McLaughlin et al., 2005). Since this report, three additional subjects were diagnosed with MDS/AML (n=8, 5%). Six are deceased at the time of this report as a result of their treatment-related MDS/AML. We observed additional deaths among patients in this study as a result of second malignancies. Among patients with lymphoma (without HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome at lymphoma diagnosis), the risk of second malignancy is higher than the general population and varies by the subtype of lymphoma, suggesting differing immunological alteration and treatment may contribute to these differences (Morton et al., 2010). Fewer cycles of FND may reduce the risk of second malignancy. DNA damaging cytotoxic agents, genetic susceptibility and immune suppression may predispose our patients to higher incidence of second malignancy that can be life threatening and must be considered when counselling patients on the late toxicity of management strategies.

Over the course of follow-up, we noted five cases (3%) of histological transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). This is favourable in comparison to the rates (14.3% and 10.7%) observed in the era of chemoimmunotherapy reported by the National LymphoCare Study (Wagner-Johnston et al., 2015) and the University of Iowa/Mayo Molecular Epidemiology Resource (Link et al., 2013), both with shorter follow-up. This may have contributed to our favourable outcomes.

With mature follow-up, we describe that prolonged PFS is possible following frontline FND with either sequential or concurrent rituximab. FLIPI scores were able to risk stratify patients, those with high-risk FLIPI having the shortest PFS and OS. Others have noted shorter PFS with higher FLIPI scores (Buske et al., 2006). Based on our review of sequential stage IV FL protocols at M. D. Anderson (Liu et al., 2006), we have speculated that more intensive therapy may be warranted for patients with high-risk FLIPI scores (Tsimberidou et al., 2002); novel therapies are also warranted for this high-risk population. Those with low or intermediate-risk FLIPI experienced favourable outcomes in our study. In addition, nearly a third of patients had low tumour burden and may have been candidates for observation, though in exploratory analyses, outcomes were not associated with tumour burden. In our study, patients with favourable risk had very favourable PFS and OS, with mature follow-up.

Based on our mature findings, patients with advanced stage, indolent lymphoma with low to intermediate risk FLIPI score had very favourable outcomes following FND with concurrent or sequential rituximab and IFN maintenance, with high response rates and robust survival. The unfavourable toxicity profile or intolerance may be overcome with a shorter induction course, such as four to six cycles of FND. With consideration of both the acute and late toxicity of FND with either concurrent or sequential rituximab and IFN maintenance, modern management strategies and novel approaches under investigation for previously untreated FL, MZL and SLL should be compared to our findings as we strive to improve outcomes for patients with indolent lymphoma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Idec/Genentech.

This study was originally presented at the 2003 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting and an update was presented at the 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting.

Grant: NIH/NCI P30 CA16672

Footnotes

DR. JASON R WESTIN (Orcid ID: 0000-0002-1824-2337)

Author’s Disclosures

Nastoupil: Honoraria- Celgene, Gilead; research funding- Janssen, TG Therapeutics, Abbvie

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Peter McLaughlin, Fernando Cabanillas

Provision of study materials or patients: Peter McLaughlin, M. Alma Rodriguez, Jorge Romaguera, Andre Goy, Fredrick B. Hagemeister, Luis Fayad

Collection and assembly of data: Loretta Nastoupil, Peter McLaughlin, Eleanor Willis, Ana Ayala, Andre Goy, Nathan Fowler

Data analysis and interpretation: Loretta Nastoupil, Peter McLaughlin, Lei Feng, Nathan Fowler, Andre Goy, M. Alma Rodriguez, Fernando Cabanillas

Manuscript writing: all authors

Final approval of manuscript: all authors

References

- BACHY E, BRICE P, DELARUE R, BROUSSE N, HAIOUN C, LE GOUILL S, DELMER A, BORDESSOULE D, TILLY H, CORRONT B, ALLARD C, FOUSSARD C, BOSLY A, COIFFIER B, GISSELBRECHT C, SOLAL-CELIGNY P, SALLES G. Long-term follow-up of patients with newly diagnosed follicular lymphoma in the prerituximab era: effect of response quality on survival–A study from the groupe d’etude des lymphomes de l’adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:822–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BUSKE C, HOSTER E, DREYLING M, HASFORD J, UNTERHALT M, HIDDEMANN W. The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) separates high-risk from intermediate- or low-risk patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma treated front-line with rituximab and the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) with respect to treatment outcome. Blood. 2006;108:1504–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-013367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHESON BD, HORNING SJ, COIFFIER B, SHIPP MA, FISHER RI, CONNORS JM, LISTER TA, VOSE J, GRILLO-LOPEZ A, HAGENBEEK A, CABANILLAS F, KLIPPENSTEN D, HIDDEMANN W, CASTELLINO R, HARRIS NL, ARMITAGE JO, CARTER W, HOPPE R, CANELLOS GP. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEDERICO M, LUMINARI S, DONDI A, TUCCI A, VITOLO U, RIGACCI L, DI RAIMONDO F, CARELLA AM, PULSONI A, MERLI F, ARCAINI L, ANGRILLI F, STELITANO C, GAIDANO G, DELL’OLIO M, MARCHESELLI L, FRANCO V, GALIMBERTI S, SACCHI S, BRUGIATELLI M. R-CVP versus R-CHOP versus R-FM for the initial treatment of patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: results of the FOLL05 trial conducted by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1506–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRIEDBERG JW, TAYLOR MD, CERHAN JR, FLOWERS CR, DILLON H, FARBER CM, ROGERS ES, HAINSWORTH JD, WONG EK, VOSE JM, ZELENETZ AD, LINK BK. Follicular lymphoma in the United States: first report of the national LymphoCare study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1202–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEROLD M, HAAS A, SROCK S, NESER S, AL-ALI KH, NEUBAUER A, DOLKEN G, NAUMANN R, KNAUF W, FREUND M, ROHRBERG R, HOFFKEN K, FRANKE A, ITTEL T, KETTNER E, HAAK U, MEY U, KLINKENSTEIN C, ASSMANN M, VON GRUNHAGEN U. Rituximab added to first-line mitoxantrone, chlorambucil, and prednisolone chemotherapy followed by interferon maintenance prolongs survival in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma: an East German Study Group Hematology and Oncology Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1986–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIDDEMANN W, KNEBA M, DREYLING M, SCHMITZ N, LENGFELDER E, SCHMITS R, REISER M, METZNER B, HARDER H, HEGEWISCH-BECKER S, FISCHER T, KROPFF M, REIS HE, FREUND M, WORMANN B, FUCHS R, PLANKER M, SCHIMKE J, EIMERMACHER H, TRUMPER L, ALDAOUD A, PARWARESCH R, UNTERHALT M. Frontline therapy with rituximab added to the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) significantly improves the outcome for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma compared with therapy with CHOP alone: results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2005;106:3725–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEATING MJ, KANTARJIAN H, TALPAZ M, REDMAN J, KOLLER C, BARLOGIE B, VELASQUEZ W, PLUNKETT W, FREIREICH EJ, MCCREDIE KB. Fludarabine: a new agent with major activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1989;74:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEATING MJ, O’BRIEN S, KANTARJIAN H, PLUNKETT W, ESTEY E, KOLLER C, BERAN M, FREIREICH EJ. Long-term follow-up of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with fludarabine as a single agent. Blood. 1993;81:2878–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEATING MJ, O’BRIEN S, ALBITAR M, LERNER S, PLUNKETT W, GILES F, ANDREEFF M, CORTES J, FADERL S, THOMAS D, KOLLER C, WIERDA W, DETRY MA, LYNN A, KANTARJIAN H. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4079–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINK BK, MAURER MJ, NOWAKOWSKI GS, ANSELL SM, MACON WR, SYRBU SI, SLAGER SL, THOMPSON CA, INWARDS DJ, JOHNSTON PB, COLGAN JP, WITZIG TE, HABERMANN TM, CERHAN JR. Rates and outcomes of follicular lymphoma transformation in the immunochemotherapy era: a report from the University of Iowa/MayoClinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence Molecular Epidemiology Resource. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3272–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Q, FAYAD L, CABANILLAS F, HAGEMEISTER FB, AYERS GD, HESS M, ROMAGUERA J, RODRIGUEZ MA, TSIMBERIDOU AM, VERSTOVSEK S, YOUNES A, PRO B, LEE MS, AYALA A, MCLAUGHLIN P. Improvement of overall and failure-free survival in stage IV follicular lymphoma: 25 years of treatment experience at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1582–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCUS R, IMRIE K, BELCH A, CUNNINGHAM D, FLORES E, CATALANO J, SOLAL-CELIGNY P, OFFNER F, WALEWSKI J, RAPOSO J, JACK A, SMITH P. CVP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CVP as first-line treatment for advanced follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:1417–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN P. The indolent B-cell lymphomas. Cancer Treat Res. 2006;131:89–120. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-29346-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN P, CABANILLAS F, HAGEMEISTER FB, SWAN F, JR, ROMAGUERA JE, TAYLOR S, RODRIGUEZ MA, VELASQUEZ WS, REDMAN JR, GUTTERMAN JU. CHOP-Bleo plus interferon for stage IV low-grade lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:205–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN P, HAGEMEISTER FB, ROMAGUERA JE, SARRIS AH, PATE O, YOUNES A, SWAN F, KEATING M, CABANILLAS F. Fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone: an effective new regimen for indolent lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996a;14:1262–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.4.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN P, ROBERTSON LE, KEATING MJ. Fludarabine phosphate in lymphoma: an important new therapeutic agent. Cancer Treat Res. 1996b;85:3–14. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4129-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCLAUGHLIN P, ESTEY E, GLASSMAN A, ROMAGUERA J, SAMANIEGO F, AYALA A, HAYES K, MADDOX AM, PRETI HA, HAGEMEISTER FB. Myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia following therapy for indolent lymphoma with fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone (FND) plus rituximab and interferon alpha. Blood. 2005;105:4573–5. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTOTO S, MORENO C, DOMINGO-DOMENECH E, ESTANY C, ORIOL A, ALTES A, BESALDUCH J, PEDRO C, GARDELLA S, ESCODA L, ASENSIO A, VIVANCOS P, GALAN P, DE SEVILLA AF, RIBERA JM, BRIONES J, COLOMER D, CAMPO E, MONTSERRAT E, LOPEZ-GUILLERMO A. High clinical and molecular response rates with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone in previously untreated patients with advanced stage follicular lymphoma. Haematologica. 2008;93:207–14. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORTON LM, CURTIS RE, LINET MS, BLUHM EC, TUCKER MA, CAPORASO N, RIES LA, FRAUMENI JF., JR Second malignancy risks after non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: differences by lymphoma subtype. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4935–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASTOUPIL LJ, SINHA R, BYRTEK M, ZIEMIECKI R, TAYLOR M, FRIEDBERG JW, KOFF JL, LINK BK, CERHAN JR, DAWSON KL, FLOWERS CR. Comparison of the effectiveness of frontline chemoimmunotherapy regimens for follicular lymphoma used in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014:1–8. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.953144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASTOUPIL LJ, SINHA R, BYRTEK M, ZIEMIECKI R, TAYLOR M, FRIEDBERG JW, KOFF JL, LINK BK, CERHAN JR, DAWSON KL, FLOWERS CR. Comparison of the effectiveness of frontline chemoimmunotherapy regimens for follicular lymphoma used in the United States. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1295–302. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.953144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUMMEL MJ, NIEDERLE N, MASCHMEYER G, BANAT GA, VON GRUNHAGEN U, LOSEM C, KOFAHL-KRAUSE D, HEIL G, WELSLAU M, BALSER C, KAISER U, WEIDMANN E, DURK H, BALLO H, STAUCH M, ROLLER F, BARTH J, HOELZER D, HINKE A, BRUGGER W. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:1203–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SALLES G, MOUNIER N, DE GUIBERT S, MORSCHHAUSER F, DOYEN C, ROSSI JF, HAIOUN C, BRICE P, MAHE B, BOUABDALLAH R, AUDHUY B, FERME C, DARTIGEAS C, FEUGIER P, SEBBAN C, XERRI L, FOUSSARD C. Rituximab combined with chemotherapy and interferon in follicular lymphoma patients: results of the GELA-GOELAMS FL2000 study. Blood. 2008;112:4824–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARGENT DJ, SHI Q, DE BOUT S, Flowers C, Fowler NH, Fu T, Hagenbeek A, Herold M, Hoster E, Huang J, Kimby E, Ladetto M, Morschhauser F, Nielsen T, Takeshita K, Valente N, Vitolo U, Zucca E, Salles GA. Evaluation of complete response rate at 30 months (CR30) as a surrogate for progression-free survival (PFS) in first-line follicular lymphoma (FL) studies: Results from the prospectively specified Follicular Lymphoma Analysis of Surrogacy Hypothesis (FLASH) analysis with individual patient data (IPD) of 3,837 patients (pts) J Clin Oncol 33, 2015 (suppl; abstr 8504) 2015 [Google Scholar]

- SMALLEY RV, ANDERSEN JW, HAWKINS MJ, BHIDE V, O’CONNELL MJ, OKEN MM, BORDEN EC. Interferon alfa combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy for patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1336–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199211053271902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SOLAL-CELIGNY P, LEPAGE E, BROUSSE N, REYES F, HAIOUN C, LEPORRIER M, PEUCHMAUR M, BOSLY A, PARLIER Y, BRICE P, Coiffier B, Gisselbrecht C, for the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte Recombinant interferon alfa-2b combined with a regimen containing doxorubicin in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma. Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1608–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311253292203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMAS JF, MONTALBAN C, DE SEVILLA AF, MARTINEZ-LOPEZ J, DIAZ N, CANALES M, MARTINEZ R, SANCHEZ-GODOY P, CABALLERO MD, PENALVER J, PRIETO E, SALAR A, BURGALETA C, QUEIZAN JA, BAJO R, DE ONA R, DE LA SERNA J. Frontline treatment of follicular lymphoma with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab followed by rituximab maintenance: toxicities overcome its high antilymphoma effect. Results from a Spanish Cooperative Trial (LNHF-03) Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:409–16. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.543717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSIMBERIDOU AM, MCLAUGHLIN P, YOUNES A, RODRIGUEZ MA, HAGEMEISTER FB, SARRIS A, ROMAGUERA J, HESS M, SMITH TL, YANG Y, AYALA A, PRETI A, LEE MS, CABANILLAS F. Fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexamethasone (FND) compared with an alternating triple therapy (ATT) regimen in patients with stage IV indolent lymphoma. Blood. 2002;100:4351–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VITOLO U, LADETTO M, BOCCOMINI C, BALDINI L, DE ANGELIS F, TUCCI A, BOTTO B, CHIAPPELLA A, CHIARENZA A, PINTO A, DE RENZO A, ZAJA F, CASTELLINO C, BARI A, ALVAREZ DE CELIS I, EVANGELISTA A, PARVIS G, GAMBA E, LOBETTI-BODONI C, CICCONE G, ROSSI G. Rituximab maintenance compared with observation after brief first-line R-FND chemoimmunotherapy with rituximab consolidation in patients age older than 60 years with advanced follicular lymphoma: a phase III randomized study by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3351–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAGNER-JOHNSTON ND, LINK BK, BYRTEK M, DAWSON KL, HAINSWORTH J, FLOWERS CR, FRIEDBERG JW, BARTLETT NL. Outcomes of transformed follicular lymphoma in the modern era: a report from the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS) Blood. 2015;126:851–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-01-621375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZINZANI PL, PULSONI A, GENTILINI P, VISANI G, PERROTTI A, MOLINARI AL, GUARDIGNI L, TANI M, VILLIVA N, STEFONI V, ALINARI L, MARTELLI M, BONIFAZI F, PILERI S, TURA S, BACCARANI M. Effectiveness of fludarabine, idarubicin and cyclophosphamide (FLUIC) combination regimen for young patients with untreated non-follicular low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004a;45:1815–9. doi: 10.1080/1042819042000219502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZINZANI PL, PULSONI A, PERROTTI A, SOVERINI S, ZAJA F, DE RENZO A, STORTI S, LAUTA VM, GUARDIGNI L, GENTILINI P, TUCCI A, MOLINARI AL, GOBBI M, FALINI B, FATTORI PP, CICCONE F, ALINARI L, MARTELLI M, PILERI S, TURA S, BACCARANI M. Fludarabine plus mitoxantrone with and without rituximab versus CHOP with and without rituximab as front-line treatment for patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004b;22:2654–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZINZANI PL, TANI M, PULSONI A, DE RENZO A, STEFONI V, BROCCOLI A, MONTINI GC, FINA M, PELLEGRINI C, GANDOLFI L, CAVALIERI E, TORELLI F, SCOPINARO F, ARGNANI L, QUIRINI F, DERENZINI E, ROSSI M, PILERI S, FANTI S, BACCARANI M. A phase II trial of short course fludarabine, mitoxantrone, rituximab followed by (9)(0)Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan in untreated intermediate/high-risk follicular lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:415–20. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]