Robert L Coleman

Prof Robert L Coleman, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,*,

Amit M Oza

Prof Amit M Oza, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Domenica Lorusso

Domenica Lorusso, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Carol Aghajanian

Carol Aghajanian, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Ana Oaknin

Ana Oaknin, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Andrew Dean

Andrew Dean, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Nicoletta Colombo

Prof Nicoletta Colombo, PhD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Johanne I Weberpals

Johanne I Weberpals, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Andrew Clamp

Andrew Clamp, PhD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Giovanni Scambia

Prof Giovanni Scambia, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Alexandra Leary

Alexandra Leary, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Robert W Holloway

Robert W Holloway, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Margarita Amenedo Gancedo

Margarita Amenedo Gancedo, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Peter C Fong

Peter C Fong, FRACP

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Jeffrey C Goh

Jeffrey C Goh, FRACP

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

David M O’Malley

David M O’Malley, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Deborah K Armstrong

Prof Deborah K Armstrong, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Jesus Garcia-Donas

Jesus Garcia-Donas, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Elizabeth M Swisher

Prof Elizabeth M Swisher, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Anne Floquet

Anne Floquet, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Gottfried E Konecny

Prof Gottfried E Konecny, MD

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Iain A McNeish

Prof Iain A McNeish, FCRP

1Department of Gynecologic Oncology and Reproductive Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1155 Herman Pressler Dr., CPB6.3590 Houston, TX 77030, USA (Prof R L Coleman MD); Department of Medicine, Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network, 610 University Avenue, Toronto M5G 2M9, Canada (Prof A M Oza MD); MITO and Gynecologic Oncology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Giacomo Venezian, 1, 20133 Milan, Italy (D Lorusso MD); Department of Medical Oncology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 300 East 66th Street, New York, NY, USA (C Aghajanian MD); Vall d’Hebron University Hospital, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), 119-129, 08035, Barcelona, Spain (A Oaknin MD); Department of Oncology, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital, 12 Salvado Rd., Subiaco, Western Australia 6008, Australia (A Dean MD); Gynecologic Cancer Program, European Institute of Oncology and University of Milan-Bicocca, Via Ripamonti 435, Milan, Italy (Prof N Colombo PhD); Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6 (J I Weberpals MD); Department of Medical Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust and University of Manchester, 550 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M20 4BX UK (A Clamp PhD); Gynecologic Oncology, Università Cattolica Roma, Largo Francesco Vito, 1, 00168 Roma, Italy (Prof G Scambia MD); GINECO and Gynecological Unit, Department of Medicine, Gustave Roussy Cancer Center and INSERM U981, 114 Rue Edouard-Vaillant, 94805, Villejuif, France (A Leary MD); Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Florida Hospital Cancer Institute, 2501 North Orange Avenue, Suite 683, Orlando, FL, USA (R W Holloway MD); Medical Oncology Department, Oncology Center of Galicia, Doctor Camilo Veiras, 1, 15009 La Coruña, Spain (M Amenedo Gancedo MD); Medical Oncology Department, Auckland City Hospital, 2 Park Rd, Grafton, Auckland 1023, New Zealand (P C Fong FRACP); Department of Oncology, Cancer Care Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Level 5 Joyce Tweddell Building, Butterfield Street, Herston, Queensland 4029, Australia (J C Goh FRACP); Gynecologic Oncology, The Ohio State University, James Cancer Center, M210 Starling Loving, 320 W 10th Ave, Columbus, OH 43210, USA (D M O’Malley MD); The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins, Room 190, 1650 Orleans Street, Baltimore, MD 21287, USA (Prof D K Armstrong MD); HM Hospitales – Centro Integral Oncológico HM Clara Campal, Calle Oña, 10, Planta -1, 28050 Madrid, Spain (J Garcia-Donas MD); University of Washington, 1959 Northeast Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195, USA (Prof E M Swisher MD); GINECO and Institut Bergonié, 229, cours de l’Argonne, 33076 Bordeaux, France (A Floquet MD); Department of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, 100 Medical Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA (Prof G E Konecny MD); Institute of Cancer Sciences, University of Glasgow, 1053 Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 0YN UK (Prof I A McNeish FCRP); Royal Melbourne Hospital, 300 Grattan Street, Parkville, Victoria, 3052, Australia (C L Scott PhD); Clovis Oncology, Inc., 5500 Flatiron Parkway, Boulder, CO 80301, USA (T Cameron MSc, L Maloney BA, J Isaacson PhD, S Goble MS, C Grace BSc, T C Harding PhD, M Raponi PhD, K K Lin PhD, H Giordano MA); Foundation Medicine, Inc., 150 Second St, Cambridge, MA, 02141, USA (J Sun PhD); UCL Cancer Institute and UCL Hospitals, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4TJ, UK (Prof J A Ledermann MD)

1,

Clare L Scott

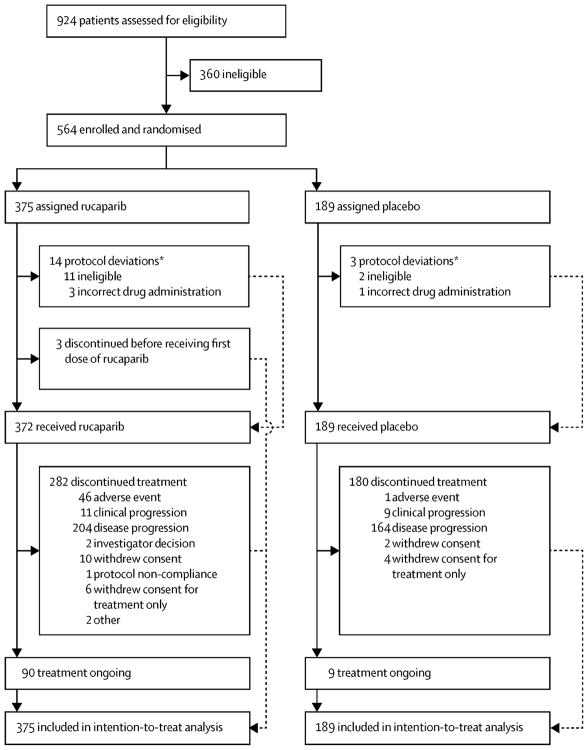

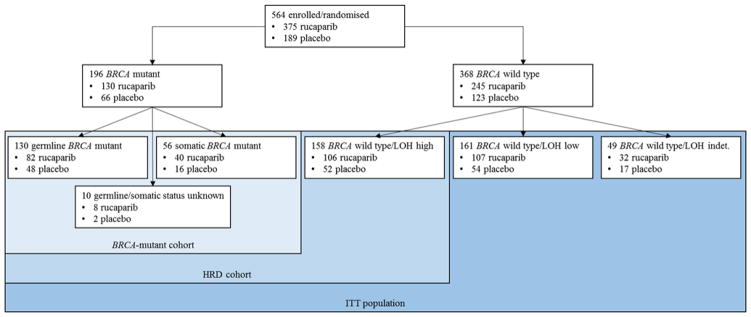

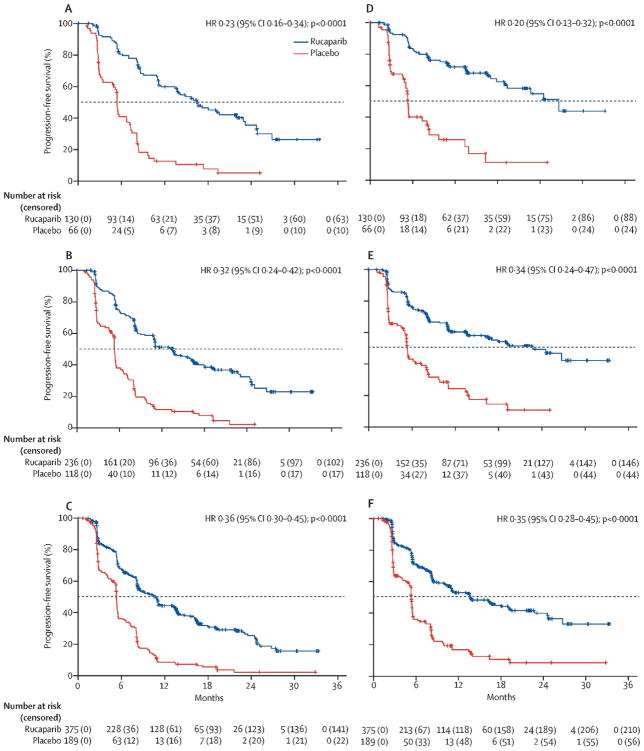

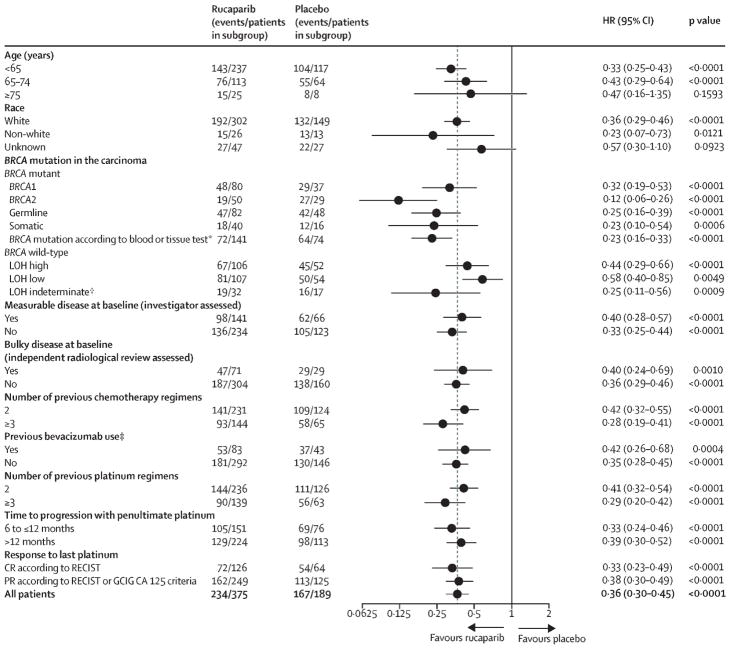

Clare L Scott, PhD