Abstract

Background

People post-stroke can learn a novel locomotor task, but require more practice to do so. Implementing an approach that can enhance locomotor learning may therefore improve post-stroke locomotor recovery. In healthy adults, an acute high-intensity exercise bout before or after a motor task may improve motor learning and has thus been suggested as a method that could be used to improve motor learning in neurorehabilitation. However, it is unclear whether an acute high-intensity exercise bout, which stroke survivors can feasibly complete in neurorehabilitation session, would generate comparable results.

Objective

To determine a feasible, high-intensity exercise protocol that could be incorporated into a post-stroke neurorehabilitation session and would result in significant exercise-induced responses.

Methods

Thirty-seven chronic stroke survivors participated. We allocated subjects to either a control (CON) or one of the exercise groups: treadmill walking (TMW), and total body exercise (TBE). The main exercise-induced measures were: average intensity (% max intensity) and time spent (absolute: seconds; normalized: % total time) at target exercise intensity, and magnitudes of change in serum lactate (mM/L) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; ng/ml).

Results

Compared to CON, both exercise groups reached and exercised longer at their target intensities and had greater responses in lactate. However, the TBE group exercised longer at target intensity and with greater lactate response than the TMW group. There were no significant BDNF responses among groups.

Conclusions

An acute high-intensity exercise bout that could be incorporated into a neurorehabilitation learning-specific session and results in substantial exercise-induced responses is feasible post-stroke.

Keywords: Stroke, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, lactate, priming, motor learning, rehabilitation

Introduction

Stroke impairs the body structures and functions necessary for movement, therefore, motor recovery is one of the focuses of post-stroke rehabilitation.1 Spontaneous recovery within the first six months post-stroke is often not sufficient to fully recover mobility,2,3 thus many people post-stroke recover their motor function via rehabilitation protocols that focus on (re)learning the motor tasks that were impaired by the stroke. The brain supports learning through neuroplasticity.4,5 Recent evidence suggests that the capacity for learning and neuroplasticity is retained following stroke;6–8 however, the amount of practice required to learn is increased and retention of what is learned is reduced compared to neurologically intact adults.9–11 Thus, incorporating strategies that can enhance learning may improve motor recovery following stroke.

Recent evidence in neurologically intact subjects suggests that a short, high-intensity exercise bout may promote learning and thus could be an important strategy to enhance post-stroke recovery.12 In neurologically intact humans, immediate increases in cognitive learning after an acute high-intensity exercise bout 13 are associated with elevated concentrations of peripheral neurophysiological correlates (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF; catecholamines). Recent studies have extended these findings to motor learning14,15 by investigating whether a short, high-intensity exercise bout would enhance learning of an upper extremity motor task.14–20 These studies showed that exercise intensity18 is a main factor that influences exercise-enhanced motor learning, and that increases in peripheral neurophysiological correlates (i.e., lactate, BDNF) are associated with motor learning gains.15

Many have proposed that the effect of exercise on motor learning may be mediated, at least in part, by BDNF.12 This neurotrophin, which is expressed in the brain and involved with neuronal transmission, modulation, plasticity, and memory formation,21,22 has been linked with both motor learning23 and exercise24 in the animal model in which BDNF was assessed directly in the brain. Studies in humans have recently measured BDNF in the blood and have shown that an acute high-intensity exercise bout increases peripheral BDNF.25 Factors like gender, exercise intensity, and presence of a neurologic condition modulate this effect in humans.25–27 Nevertheless, it is still unclear whether peripheral exercise-induced changes in serum BDNF are a reflection of central BDNF changes.

Based on these findings, it was suggested that acute high-intensity exercise might be a potential “primer” of motor learning in clinical cohorts (e.g., stroke), who have motor learning deficits,12,28 and that this type of priming might be cost-effective, and relatively feasible to implement in neurorehabilitation.29,30 However, the practicality of the protocols used in the previous studies is questionable for use in neurorehabilitation, particularly in patients with motor deficits, such as people post-stroke. Specifically, the majority of the exercise protocols utilize more than 15 minutes of high-intensity interval training.14,16,18 Recent studies have shown that while stroke survivors are capable of completing high-intensity interval training,31,32 this exercise typically constitutes the entire neurorehabilitation session, due to both time and subject fatigue.31,32 Thus, the aforementioned exercise protocols may not be feasible to use as a “primer” of motor learning in persons post-stroke since they would consume the neurorehabilitation session,33 eliminating the practice of motor tasks whose learning they were supposed to facilitate.

The aim of the present study, therefore, was to determine a feasible method for completing a short high-intensity exercise bout34 in people post-stroke that would result in significant exercise-induced responses, yet not to consume a substantial portion of the neurorehabilitation session and/or cause significant fatigue that would prevent completion motor practice of a novel task. The overall goal was to design a protocol that would allow practical clinical application in neurorehabilitation settings to facilitate motor learning in people post-stroke.

Methods

The study conforms to the CONSORT guidelines. All experimental procedures took place in the Neuromotor Behavior Lab located in the STAR complex at the University of Delaware, Newark, DE.

Subjects

Thirty-seven stroke survivors participated. Subjects were included if they met the following criteria: 1) age 21–85, 2) unilateral, chronic stroke(s) (>6 months post-stroke), confirmed by MRI or CT scan, 3) able to walk for 4 minutes at self-selected speed (SSWS) without assistance from another person (assistive device allowed), 4) resting heart rate (HR) between 40–100 beats per minute, and 5) resting blood pressure between 90/60 to 170/90. Exclusion criteria were: 1) evidence of cerebellar stroke on clinical MRI or CT scan, 2) other neurologic conditions in addition to stroke, 3) lower limb Botulinum toxin injection <4 months earlier, 4) current participation in physical therapy, 5) inability to walk outside the home prior to the stroke, 6) coronary artery bypass graft or myocardial infarction within past 3 months, 7) musculoskeletal pain that limits walking, 8) inability to communicate with investigators, 9) neglect, and 10) unexplained dizziness in last 6 months. All subjects read and signed written informed consent approved by the local Institutional Review Board adhering to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental Procedures

First, subjects completed certain clinical tests (baseline blood pressure and HR, Lower Extremity Fugl-Meyer (FMLE),35 and SSWS).36 The data collected were part of a larger motor learning study (three sessions: initial evaluation and two experimental) where subjects completed 15 minutes of a novel walking task, either immediately before or after exercise (first experimental session). This design allowed us to determine whether an exercise protocol could be feasibly combined with motor practice, such as would occur in a neurorehabilitation session. The whole experiment (first experimental session: exercise, motor practice, blood collection, and subject’s preparation) lasted an average of 75 minutes. Given the study’s goal, we used the previous work14,15 in healthy subjects as a guide. Specifically, we aimed to design the exercise protocol(s) to be of high-intensity and of sufficient duration to observe a significant increase in lactate, while not generating significant fatigue or take significant time that would limit the practice of motor learning tasks. Previous studies found an average increase >10mM/L of lactate with exercise14,15,18 and while we believed this level of increase would likely be difficult to obtain with a shorter protocol in people post-stroke, our goal was to determine a high-intensity exercise protocol that would result in the greatest lactate increase without causing significant fatigue that would limit coupled motor practice. We quantified exercise intensity using two methods based on beta-blocker intake. This drug class is commonly used by those post-stroke and alter the HR response to exercise.37 For those subjects not on beta-blocker medication, the target exercise range was defined as 70–85 % of age-predicted HR max (HRmax = 220 - age).38 For those on beta-blocker medication, the target exercise intensity range was defined as 13–15 on the 6–20 Rate of Perceived Exertion scale (RPE).39,40 We chose those ranges because they indicate high-intensity exercise.38 We monitored the exercise intensity in real time by monitoring the HR continuously and recording every 15 seconds using a HR monitor (Polar Electro Inc., Lake Success, NY, USA) and asking subjects to rate their perceived exertion using the RPE scale every 30 seconds. Following ACSM guidelines,38 exercise was terminated if subjects requested termination or demonstrated increase pallor, excessive diaphoresis, dyspnea, chest pain or angina, nausea, dizziness, pain.

Initially, we tested an upper body ergometer (UBE) exercise protocol that generated significant changes in BDNF and lactate in neurologically intact subjects34 with a short exercise bout (~5 min). We were particularly interested in applying this protocol because ultimately, the goal was to examine the effect of exercise “priming” on locomotor learning post-stroke, and thus we were interested in a high-intensity exercise protocol that could avoid leg use. Three subjects (2 males; 71 ± 12 years; 10 ± 5 months post-stroke; 2 right hemiparesis) completed two 2-minute bouts of UBE with the goal of achieving the target high-intensity range. However, this exercise protocol was determined not feasible because none of the subjects were able to perform UBE with sufficient resistance and at a sufficient speed to reach their target intensity range (peak intensity: 57 ± 9 % HRmax).

Given UBE protocol was unsuccessful,34 we tested two other protocols that each had advantages over UBE; walking on a treadmill at a fast-comfortable speed and arm and leg cycling on a seated ergometer. We specifically chose these two protocols because the former has the advantage of the experimenter being able to control the speed (and therefore, to some extent, the intensity) and the latter has the advantage of being feasible for a larger number of stroke survivors. Both devices are widely available in rehabilitation settings.

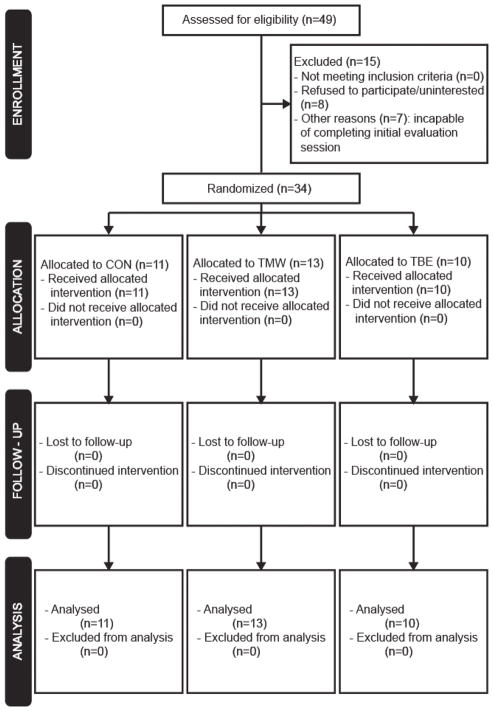

A total of forty-nine subjects were assessed for eligibility, fifteen were excluded (Figure 1). Thirty-four subjects were randomly allocated to either a control (CON) group or one of the two exercise groups: treadmill walking (TMW), and total body exercise (TBE). The goal for all groups was to exercise continuously in a single bout for approximately 5 minutes and for the exercise groups to exercise within a high-intensity range (70–85% HRmax or 13–15 RPE for the beta-blocker users). Prior to any experimental procedures, the fastest comfortable walking speed was determined. Subjects walked first at 0.2 m/sec on the treadmill, and then we increased the speed gradually (0.05 m/sec every 15 seconds) until the subjects reported they had reached their fast walking speed. Furthermore, subjects in CON and TMW groups wore a ceiling mounted harness without body weight support, and held onto the front handrail.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

CON

Eleven subjects walked on a treadmill at 25% of their fastest comfortable speed. This group acted as an active control group to test for the possibility of any effects of low intensity exercise.

TMW

Thirteen subjects walked on a treadmill starting at their fastest comfortable speed. To reach and remain within the high-intensity range, we modulated the treadmill speed based on exercise intensity.

TBE

Ten subjects cycled on a total body exerciser (SCIFIT, Tulsa, OK, USA) using either upper, lower, or both extremities, based on their ability (5: both arms and legs; 2: both legs; 3: non-affected arm and leg). Subjects pedaled at high resistance and fast speed, which we modulated throughout so the exercise intensity was within the high-intensity range based on either HR or RPE.

Serum Blood Biomarkers Collection and Analysis

To quantify the exercise-induced changes in lactate and BDNF, we collected two 6 mL blood samples from all subjects. Before exercise onset, a registered nurse inserted an intravenous catheter in subject’s forearm, and then serum samples were collected immediately pre- and post-exercise samples, which indicate the baseline concentrations and exercise-induced changes, respectively. Immediately after, samples sat at room temperature for 30 minutes to allow clotting, samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 minutes.

Samples were divided offline into several aliquots in microcentrifuge tubes designated for lactate and BDNF and stored at 80°C until assayed. Next, we analyzed lactate and BDNF levels using the Lactate Colorimetric Assay Kit II (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and the Human BDNF Quantikine Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), respectively. Both correlates were further analyzed using the corresponding protocols put forth by each manufacturer and the same procedures from our previous work.34

Data and Statistical Analyses

To test whether high-intensity exercise induced significant changes, we measured exercise intensity (% max intensity) at the beginning and end of the exercise bout, and lactate immediately pre- and post-exercise. To quantify whether subjects exercised at the high-intensity range (one measure) and for how long (two measures), we calculated three measures using either HR or RPE (for those not taking and those taking beta-blocker medications, respectively): average exercise intensity (% max intensity) and time spent (absolute: seconds; normalized: % total exercise period) at the target intensity range. There were a few subjects in each group who were on beta-blocker medication, and therefore, using heart rate response was not adequate for quantifying exercise intensity across participants within each group. Thus, we created a new metric that represents intensity, whether determined by heart rate or RPE, as a percent of the maximum achievable intensity. For the average exercise intensity, we calculated the average HR or RPE at the target intensity and then divided by the max ([average HR/HRmax] *100 or [average RPE/RPEmax] *100). Specifically in the case of the RPE scores, we did not convert a nominal measure to continuous measure, but rather simply created a new measure. For the time at target intensity, we calculated first the absolute time (minutes) spent in the target intensity range (70–85% HRmax or 13–15 RPE for the beta-blocker users) and then divided by the total exercise time (i.e., normalized). To examine the exercise effect on the peripheral blood biomarkers, we calculated the magnitude of change (post-exercise – pre-exercise) for both lactate (mM/L) and BDNF (ng/ml).

All data are presented as means ± SD, and we used the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess whether the data were normally distributed. We tested 1) whether high-intensity exercise induced significant changes (two-way mixed ANOVA: Time [pre, post] X Groups [CON, TMW, TBE]), and 2) the exercise effect between groups (one-way independent ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis H test). When main interaction or effects were detected, post-hoc comparisons (either independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test) were completed. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

All subjects successfully completed the exercise bouts for the target duration without any rest breaks or adverse events (e.g., nausea, lightheadedness, pain). In both exercise groups, the HR and blood pressure of all subjects returned to baseline levels within 5 minutes following exercise. In addition to the exercise protocol, all subjects successfully completed 15-minutes practice of novel locomotor task (before: CON and TMW; after: TBE) in the same session.

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical information for all subjects. Among groups, no significant differences were found in any demographic (age: p = 0.415) or clinical measures (SSWS: p = 0.919; FMLE: p = 0.702). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in post-stroke period among groups (p = 0.890), with the larger average and variance in the TBE group driven by a single subject.

Table 1.

Subject demographics and clinical measurements

| Subject | Group (CON/TMW/TBE) | Gender (M/F) | Age (years) | Hemiparetic Limb (R/L) | Post-Stroke Period (months) | SSWS (m/s) | FMLE (max 34) | Beta-Blocker Use (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CON | F | 57 | R | 15 | 0.65 | 15 | Y |

| 2 | CON | M | 60 | R | 43 | 1.15 | 16 | N |

| 3 | CON | M | 38 | L | 22 | 1.39 | 30 | Y |

| 4 | CON | M | 49 | L | 22 | 1.27 | 22 | N |

| 5 | CON | M | 69 | R | 67 | 0.54 | 18 | N |

| 6 | CON | M | 58 | R | 48 | 0.40 | 16 | N |

| 7 | CON | F | 62 | R | 47 | 0.90 | 30 | N |

| 8 | CON | M | 72 | R | 23 | 1.00 | 29 | N |

| 9 | CON | M | 55 | L | 51 | 0.68 | 19 | Y |

| 10 | CON | M | 50 | L | 93 | 0.94 | 29 | N |

| 11 | CON | M | 54 | L | 34 | 0.34 | 13 | Y |

| 12 | TMW | F | 36 | R | 14 | 0.80 | 12 | Y |

| 13 | TMW | M | 58 | L | 23 | 0.52 | 20 | N |

| 14 | TMW | M | 60 | L | 14 | 0.67 | 15 | N |

| 15 | TMW | F | 61 | R | 168 | 0.70 | 15 | N |

| 16 | TMW | M | 60 | R | 27 | 0.51 | 18 | N |

| 17 | TMW | M | 68 | L | 10 | 1.14 | 32 | N |

| 18 | TMW | F | 75 | R | 63 | 0.73 | 22 | Y |

| 19 | TMW | M | 67 | R | 62 | 1.13 | 24 | N |

| 20 | TMW | M | 28 | L | 61 | 1.50 | 26 | N |

| 21 | TMW | M | 77 | L | 25 | 1.08 | 22 | N |

| 22 | TMW | F | 55 | L | 65 | 0.45 | 25 | Y |

| 23 | TMW | M | 84 | R | 38 | 0.55 | 24 | Y |

| 24 | TMW | F | 63 | L | 40 | 0.73 | 30 | Y |

| 25 | TBE | F | 69 | L | 48 | 1.30 | 29 | Y |

| 26 | TBE | M | 45 | L | 303 | 0.82 | 19 | N |

| 27 | TBE | M | 69 | R | 168 | 0.86 | 19 | N |

| 28 | TBE | F | 78 | R | 27 | 0.63 | 33 | N |

| 29 | TBE | M | 59 | R | 9 | 0.53 | 23 | Y |

| 30 | TBE | F | 47 | L | 36 | 0.56 | 28 | N |

| 31 | TBE | F | 63 | L | 36 | 0.93 | 30 | N |

| 32 | TBE | M | 71 | L | 16 | 0.39 | 12 | N |

| 33 | TBE | M | 64 | L | 74 | 0.79 | 14 | Y |

| 34 | TBE | M | 75 | R | 38 | 1.05 | 32 | N |

|

| ||||||||

| CON | N=11 | 9 M | 57 ± 9 | 6 R | 42 ± 23 | 0.84 ± 0.35 | 22 ± 7 | 4 Y |

| TMW | N=13 | 8 M | 61 ± 15 | 6 R | 47 ± 42 | 0.81 ± 0.31 | 22 ± 6 | 5 Y |

| TBE | N=10 | 6 M | 64 ± 11 | 4 R | 76 ± 92 | 0.79 ± 0.27 | 24 ± 7 | 3 Y |

Abbreviations: CON, control; TMW, treadmill walking; TBE, total body exercise; M, male; F, female; R, right; L, left; SSWS, self-selected walking speed; FMLE, Fugl-Meyer lower extremity; Y, yes; N, no.

Table 2 presents the group mean changes for intensity and lactate for which significant main and interaction effects were observed. There were no differences in intensity at the start of exercise (all p > 0.05). As expected, intensity significantly changed from the beginning to the end of exercise only in the exercise groups (CON: p = 0.104; TMW: p < 0.001; TBE: p < 0.001). Among groups, lactate levels were similar pre-exercise ( p > 0.05 in all groups). As anticipated, only the exercise groups (p < 0.001 in both groups) showed significant changes from pre- to post-exercise (CON: p = 0.592).

Table 2.

Exercise-induced changes in intensity and lactate (mean ± SD)

| Measures | Time | Groups | Time | Group | Time X Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| CON (N=11) | TMW (N=13) | TBE (N=10) | P value | ||||

| Exercise Intensity (% max intensity) | Start | 44 ± 13 | 39 ± 8 | 44 ± 10 | <0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| End | 49 ± 10 | 78 ± 11*¥ | 77 ± 5*¥ | ||||

| Lactate (mM/L) | Pre-Exercise | 1.87 ± 1.08 | 1.52 ± 0.57 | 2.36 ± 1.14 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Post-Exercise | 2.04 ± 1.17 | 3.74 ± 0.91*¥ | 8.46 ± 2.01*†¥ | ||||

The symbols * and † denote significant difference with CON and TMW, respectively

The symbol ¥ significant difference within group between time points.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CON, control; TMW, treadmill walking; TBE, total body exercise.

Table 3 presents group means for all exercise-related measures. A significant exercise effect was found for all measures but BDNF. As designed, the CON group exercised at average intensities below the high-intensity (range of average intensity throughout exercise bout: 30–66 % max intensity) and therefore, all values related to high intensity exercise are zero. Conversely, the TMW (p < 0.001) and TBE (p < 0.001) groups exercised at significantly higher average exercise intensities than the CON group. Both TMW and TBE groups exercised at similar average intensity (p = 0.532). Compared to the CON group, both TMW (both absolute and normalized: p < 0.001) and TBE (both absolute and normalized: p < 0.001) groups exercised significantly longer at the target intensity. The TBE group spent significantly more time at the target intensity than the subjects in the TMW group (absolute: p = 0.002; normalized: p = 0.030). TMW (p < 0.001) and TBE (p < 0.001) groups had greater lactate changes than the CON group. While both exercise groups reached similar average exercise intensities, the TBE group had greater lactate changes than TMW (p < 0.001). The BDNF responses did not differ among groups.

Table 3.

Exercise-related measures (mean ± SD)

| Group | Main Effect | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| CON (N=11) | TMW (N=13) | TBE (N=10) | P Value | |

| Average Intensity at Target Intensity (% max intensity) | 0 ± 0 | 70 ± 21* | 76 ± 6* | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Time at Target Intensity (minutes) | 0 ± 0 | 2.5 ± 1.4* | 4.0 ± 0.5*† | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Time at Target Intensity (% total time) | 0 ± 0 | 60 ± 27* | 79 ± 11*† | 0.030 |

|

| ||||

| ΔLactate (mM/L) | 0.16 ± 1.02 | 2.22 ± 0.81* | 6.10 ± 1.88*† | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| ΔBDNF (ng/ml) | −5.15 ± 13.60 | −1.07 ± 9.74 | 1.08 ± 12.22 | 0.573 |

The symbol Δ denotes change while the symbols * and † denote significant difference with CON and TMW, respectively

Value 0 indicates that no subject in the CON group reached and exercised at the target intensity.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; CON, control; TMW, treadmill walking; TBE, total body exercise.

Discussion

Recent studies have suggested that acute high-intensity exercise might be a potential “primer” of motor learning in clinical populations (e.g., stroke) that have motor learning deficits,12,28 and that this type of priming might be cost-effective and feasible to implement in neurorehabilitation.29,30 However, the practicality of the protocols on which these suggestions are based are questionable for neurorehabilitation due to the amount of time and effort spent in the exercise “priming”.14–18,20 We designed this study, therefore, to determine a feasible protocol that would result in exercise-induced responses and would not be expected to cause fatigue or consume a significant amount of a rehabilitation session in people post-stroke. Our results showed that subjects allocated to either high-intensity exercise group could exercise at the target intensity for more than half of the total exercise time and that this resulted in significant increases in lactate and still allowed for 15 minutes of practice of a novel walking task. There were however, significant differences between the two exercise groups that should be considered.

Subjects in both high-intensity exercise groups reached and exercised at the target intensity. However, subjects in the TBE group spent more time exercising within that target intensity than those in the TMW group. This might be due to the combination of the intensity manipulation and mechanical demands of each protocol. In the TBE group (5: both arms and legs; 2: both legs; 3: non-affected arm and leg), eight subjects used some combination of both upper and lower extremities, which may have contributed to their ability to exercise at higher intensities for a longer time. In addition, in the treadmill-walking group, speed manipulation was limited by the subject’s safety such that often the speed had to be increased slowly taking longer to increase the treadmill speed to a level where subjects reached the target intensity, thus resulting in less time exercising at the target intensity. Safety and balance during treadmill walking also influenced the total time subjects in these groups exercised.

Given that exercise-induced lactate changes were associated with learning gains in neurologically intact subjects,15 we measured lactate as a proxy of exercise intensity. As anticipated, lactate did not change in the CON group, but did change significantly in both high-intensity exercise groups, with greater changes in the ergometer group compared to the treadmill group. During treadmill walking, it is the leg muscles that are mainly active and likely contributing to changes in lactate, whereas during the TBE protocol, changes in lactate come from all of the extremities used. Previous work reported that arm cycling increased lactate levels faster and about 7.5 times more than lower extremity cycling in neurologically intact subjects during a four-minute exercise bout.45 Thus, the greater changes in lactate in the TBE group may be related not only to the longer time exercising at the target intensity, but also to the incorporation of the upper extremities into the exercise. Together these results suggest a seated exercise protocol that utilizes both upper and lower extremities may provide people post-stroke with a permissive environment (i.e., seated support, use of any extremity) in which they can exercise at high-intensity for periods that result in greater increases in lactate.

Until recently, lactate has been mainly considered as a metabolic agent.46 However, recent work has suggested lactate to be a potential factor in the effects of cardiovascular exercise on motor learning15 due to its role in multiple brain functions (i.e., neuronal metabolism, neuroprotection, long-term memory formation).47–49 Studies in which lactate was intravenously infused in healthy adults showed that lactate increases induced increases in serum BDNF50 and motor cortical plasticity.51 Recent work in humans demonstrated a strong correlation between changes in lactate with an acute high-intensity exercise bout and motor learning,15 suggesting that exercise-induced lactate changes might be related to motor learning gains. Consequently, with new knowledge arising about lactate and its function, future work should investigate whether exercise-induced lactate changes can predict exercise-induced learning gains in neurological populations.

In the animal model, exercise has been linked with neuroplasticity and motor recovery, and BDNF has been proposed to be their linkage.12,52 Previous studies in neurologically intact humans found an increase in peripheral serum BDNF following acute high-intensity exercise.15 We recently reported greater changes in peripheral serum BDNF after a short 5 minute high-intensity upper extremity cycling protocol (i.e., UBE) in young, neurologically intact subjects.34 In this study, therefore, we anticipated significant exercise-induced BDNF responses in the high-intensity exercise groups even with a short exercise bout. However, this was not what was found.

There are several possible reasons for this result. A number of factors influences peripheral circulating BDNF, including age and neurologic damage (e.g., spinal cord injury).25 Compared to previous studies,13,15 subjects in the present study were older in age and had sustained a stroke; therefore, it is likely that both these factors influenced the response of peripheral serum BDNF to exercise.27 Another factor, which must be considered, is whether peripheral measures of serum BDNF reflect changes in central BDNF 53 that have been directly linked to neuroplasticity.22,54 Currently, this remains a controversial topic (see 15 for a discussion) with no clear evidence that peripheral changes in serum BDNF reflect changes in central BDNF. This, together with previous results showing the effects of age, gender and neurologic condition on peripheral measures of BDNF,25–27 suggest that future studies should carefully consider the utility of peripheral, serum BDNF as a biomarker of the effects on exercise on central neural processes in those post-stroke.

This study had a few methodological considerations. First, we did not assess exercise-induced fatigue using a quantitative test. However, all subjects successfully completed 15 minutes of the novel walking task in addition to exercise and no subject reported total fatigue. Naturally, a formal measure of fatigue would have provided additional insight. Lastly, though both exercise groups reached and exercised at the target range with significant changes in intensity and lactate, neither group reached the post-exercise lactate levels (>10 mM/L) that have been previously reported in the studies in healthy adults.15,18 The shorter exercise bout used in the present study compared to previous work may contribute to <10 mM/L values observed in our clinical cohort. Whether there is a necessary lactate level that needs to be achieved to promote learning is unknown.

Clinical Implications

We selected these two exercise protocols due to their potential for realistic application in neurorehabilitation settings. While our results demonstrated that both high-intensity exercise protocols were feasible and resulted in statistically significant increases in lactate, the TBE protocol appears to have an advantage over the treadmill exercise protocol, in terms of amount of time that is spent at a high-intensity and in terms of changes in lactate. This is encouraging because an advantage of the seated ergometer exercise protocol is that stroke survivors with severe impairment can still complete it without the limitation of balance and safety, two factors that can limit the use of treadmill exercise protocol as a “primer” in this cohort.

Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that people with chronic stroke can complete a short high-intensity exercise bout that induces exercise-related responses in lactate levels without consuming a significant portion of the neurorehabilitation session or causing significant fatigue, therefore making it possible to couple such exercise with motor practice. Future studies should investigate whether coupling such an exercise protocol with locomotor practice can improve locomotor learning after stroke.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This material is the result of work supported in part by the National Institute of Health [grant number 2T32HD007490-16]; National Institute of Health [grant number 1R01HD078330-01A1]; National Institute of Health [grant number S10RR028114-01A1]; and Delaware Economic Development Fund [grant number 16A00377].

The authors thank the stroke survivors who participated in the study, and Carolina C. Alcantara, PT, MS, and Margaret French, PT, DPT, for their help in data collection.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Langhorne P, Bernhardt J, Kwakkel G. Stroke rehabilitation. Lancet. 2011;377(9778):1693–1702. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60325-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Kordelaar J, van Wegen E, Kwakkel G. Impact of time on quality of motor control of the paretic upper limb after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(2):338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncan PW, Goldstein LB, Matchar D, Divine GW, Feussner J. Measurement of motor recovery after stroke. Outcome assessment and sample size requirements. Stroke. 1992;23(8):1084–1089. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.8.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kleim JA, Jones TA. Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51(1):S225–239. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleim JA, Barbay S, Nudo RJ. Functional reorganization of the rat motor cortex following motor skill learning. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80(6):3321–3325. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nudo RJ, Wise BM, SiFuentes F, Milliken GW. Neural substrates for the effects of rehabilitative training on motor recovery after ischemic infarct. Science. 1996;272(5269):1791–1794. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5269.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nudo RJ, Milliken GW. Reorganization of movement representations in primary motor cortex following focal ischemic infarcts in adult squirrel monkeys. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75(5):2144–2149. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liepert J, Bauder H, Wolfgang HR, Miltner WH, Taub E, Weiller C. Treatment-induced cortical reorganization after stroke in humans. Stroke. 2000;31(6):1210–1216. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savin DN, Tseng SC, Whitall J, Morton SM. Poststroke hemiparesis impairs the rate but not magnitude of adaptation of spatial and temporal locomotor features. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2013;27(1):24–34. doi: 10.1177/1545968311434552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyrell CM, Helm E, Reisman DS. Learning the spatial features of a locomotor task is slowed after stroke. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112(2):480–489. doi: 10.1152/jn.00486.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malone LA, Bastian AJ. Spatial and temporal asymmetries in gait predict split-belt adaptation behavior in stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2014;28(3):230–240. doi: 10.1177/1545968313505912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mang CS, Campbell KL, Ross CJ, Boyd LA. Promoting neuroplasticity for motor rehabilitation after stroke: considering the effects of aerobic exercise and genetic variation on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Physical therapy. 2013;93(12):1707–1716. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter B, Breitenstein C, Mooren FC, et al. High impact running improves learning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2007;87(4):597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roig M, Skriver K, Lundbye-Jensen J, Kiens B, Nielsen JB. A single bout of exercise improves motor memory. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skriver K, Roig M, Lundbye-Jensen J, et al. Acute exercise improves motor memory: exploring potential biomarkers. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2014;116:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas R, Beck MM, Lind RR, et al. Acute Exercise and Motor Memory Consolidation: The Role of Exercise Timing. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:6205452. doi: 10.1155/2016/6205452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas R, Flindtgaard M, Skriver K, et al. Acute exercise and motor memory consolidation: Does exercise type play a role? Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2016 doi: 10.1111/sms.12791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas R, Johnsen LK, Geertsen SS, et al. Acute Exercise and Motor Memory Consolidation: The Role of Exercise Intensity. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mang CS, Snow NJ, Wadden KP, Campbell KL, Boyd LA. High-Intensity Aerobic Exercise Enhances Motor Memory Retrieval. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(12):2477–2486. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snow NJ, Mang CS, Roig M, McDonnell MN, Campbell KL, Boyd LA. The Effect of an Acute Bout of Moderate-Intensity Aerobic Exercise on Motor Learning of a Continuous Tracking Task. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0150039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Medina JH. BDNF and memory formation and storage. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry. 2008;14(2):147–156. doi: 10.1177/1073858407305850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibon J, Barker PA. Neurotrophins and Proneurotrophins. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry. 2017;0(0):1073858417697037. doi: 10.1177/1073858417697037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ploughman M, Windle V, MacLellan CL, White N, Dore JJ, Corbett D. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor contributes to recovery of skilled reaching after focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2009;40(4):1490–1495. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.531806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasmussen P, Brassard P, Adser H, et al. Evidence for a release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from the brain during exercise. Exp Physiol. 2009;94(10):1062–1069. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.048512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knaepen K, Goekint M, Heyman EM, Meeusen R. Neuroplasticity - exercise-induced response of peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a systematic review of experimental studies in human subjects. Sports medicine (Auckland, NZ) 2010;40(9):765–801. doi: 10.2165/11534530-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szuhany KL, Bugatti M, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of the effects of exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Journal of psychiatric research. 2015;60:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos GL, Alcantara CC, Silva-Couto MA, Garcia-Salazar LF, Russo TL. Decreased Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Serum Concentrations in Chronic Post-Stroke Subjects. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2016;25(12):2968–2974. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roig M, Thomas R, Mang CS, et al. Time-Dependent Effects of Cardiovascular Exercise on Memory. Exercise and sport sciences reviews. 2016;44(2):81–88. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stoykov ME, Madhavan S. Motor priming in neurorehabilitation. Journal of neurologic physical therapy : JNPT. 2015;39(1):33–42. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoykov ME, Corcos DM, Madhavan S. Movement-Based Priming: Clinical Applications and Neural Mechanisms. Journal of motor behavior. 2017;49(1):88–97. doi: 10.1080/00222895.2016.1250716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyne P, Dunning K, Carl D, Gerson M, Khoury J, Kissela B. Within-session responses to high-intensity interval training in chronic stroke. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(3):476–484. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carl DL, Boyne P, Rockwell B, et al. Preliminary safety analysis of high-intensity interval training (HIIT) in persons with chronic stroke. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42(3):311–318. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang CE, Macdonald JR, Reisman DS, et al. Observation of amounts of movement practice provided during stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(10):1692–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helm EE, Matt KS, Kirschner KF, Pohlig RT, Kohl D, Reisman DS. The influence of high intensity exercise and the Val66Met polymorphism on circulating BDNF and locomotor learning. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2017;144:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fugl-Meyer AR, Jaasko L, Leyman I, Olsson S, Steglind S. The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975;7(1):13–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flansbjer UB, Holmback AM, Downham D, Patten C, Lexell J. Reliability of gait performance tests in men and women with hemiparesis after stroke. Journal of rehabilitation medicine : official journal of the UEMS European Board of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2005;37(2):75–82. doi: 10.1080/16501970410017215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durstine JL, Moore GE, Medicine ACoS, Painter PL. ACSM’s Exercise Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Disabilities. Human Kinetics Publishers; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pescatello LS, Medicine ACoS. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2013. pp. 56–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goss FL, Robertson RJ, Haile L, Nagle EF, Metz KF, Kim K. Use of ratings of perceived exertion to anticipate treadmill test termination in patients taking beta-blockers. Perceptual and motor skills. 2011;112(1):310–318. doi: 10.2466/06.10.15.PMS.112.1.310-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borg G. Ratings of perceived exertion and heart rates during short-term cycle exercise and their use in a new cycling strength test. International journal of sports medicine. 1982;3(3):153–158. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1026080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pascual-Leone A, Grafman J, Hallett M. Modulation of cortical motor output maps during development of implicit and explicit knowledge. Science. 1994;263(5151):1287–1289. doi: 10.1126/science.8122113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karni A, Meyer G, Rey-Hipolito C, et al. The acquisition of skilled motor performance: fast and slow experience-driven changes in primary motor cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(3):861–868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivey FM, Macko RF, Ryan AS, Hafer-Macko CE. Cardiovascular health and fitness after stroke. Topics in stroke rehabilitation. 2005;12(1):1–16. doi: 10.1310/GEEU-YRUY-VJ72-LEAR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nepveu JF, Thiel A, Tang A, et al. A Single Bout of High-Intensity Interval Training Improves Motor Skill Retention in Individuals With Stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1545968317718269. 1545968317718269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borg G, Hassmen P, Lagerstrom M. Perceived exertion related to heart rate and blood lactate during arm and leg exercise. European journal of applied physiology and occupational physiology. 1987;56(6):679–685. doi: 10.1007/BF00424810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hall MM, Rajasekaran S, Thomsen TW, Peterson AR. Lactate: Friend or Foe. PM R. 2016;8(3 Suppl):S8–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Proia P, Di Liegro CM, Schiera G, Fricano A, Di Liegro I. Lactate as a Metabolite and a Regulator in the Central Nervous System. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016;17(9) doi: 10.3390/ijms17091450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steinman MQ, Gao V, Alberini CM. The Role of Lactate-Mediated Metabolic Coupling between Astrocytes and Neurons in Long-Term Memory Formation. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2016;10:10. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2016.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barros LF. Metabolic signaling by lactate in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(7):396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schiffer T, Schulte S, Sperlich B, Achtzehn S, Fricke H, Struder HK. Lactate infusion at rest increases BDNF blood concentration in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2011;488(3):234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coco M, Alagona G, Rapisarda G, et al. Elevated blood lactate is associated with increased motor cortex excitability. Somatosens Mot Res. 2010;27(1):1–8. doi: 10.3109/08990220903471765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cotman CW, Berchtold NC, Christie L-A. Exercise builds brain health: key roles of growth factor cascades and inflammation. Trends in neurosciences. 2007;30(9):464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lanz TA, Bove SE, Pilsmaker CD, et al. Robust changes in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) mRNA and protein across the brain do not translate to detectable changes in BDNF levels in CSF or plasma. Biomarkers : biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals. 2012;17(6):524–531. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.694476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gomez-Palacio-Schjetnan A, Escobar ML. Neurotrophins and synaptic plasticity. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2013;15:117–136. doi: 10.1007/7854_2012_231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]