Abstract

Aims

While cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention traditionally emphasizes risk-factor control, recent evidence also supports the promotion of “health-factors” associated with cardiovascular wellness. However, whether such health-factors exist among adults with advanced subclinical atherosclerosis is unknown. We aimed to study the association between health-factors and events among persons with elevated coronary artery calcium (CAC).

Methods and Results

Self-reported health-factors studied included non-smoking, physical activity, Mediterranean-style diet, sleep quality, emotional support, low stress burden, and absence of depression. Measured health-factors included optimal weight, blood pressure, lipids, and glucose. Multivariable-adjusted Cox models examined the association between health-factors and incident CVD or mortality, independent of risk-factor treatment. Accelerated failure-time models assessed whether health-factors were associated with relative time-delays in disease onset. Among 1,601 Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis participants with CAC>100, without baseline clinical ASCVD, mean age was 69 (±9) years, 64% were male, and median CAC score was 332 Agatston-units. Over 12 years follow-up, non-smoking, HDL-C levels >40 mg/dL for men and >50 mg/dL for women, and low stress burden were inversely associated with ASCVD (Hazard Ratios [HRs] ranging from 0.58 to 0.71, all p<0.05). Non-smoking, glucose levels <100 mg/dL, regular physical activity, and low stress burden were inversely associated with mortality (HRs ranging from 0.40 to 0.77, all p<0.05). Each of these factors was also associated with delays in onset of clinical disease, as was absence of depression.

Conclusions

Adults with elevated CAC appear to have healthy lifestyle options to lower risk and delay onset of CVD, over and above standard preventive therapies.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Calcium, Health Factors, Cardiovascular Wellness, Cardiovascular Disease Prevention

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) prevention has historically focused on controlling and treating traditional risk factors that are associated with adverse clinical events.1,2 This “high-risk” approach aims to reduce cardiovascular illness. However, it is increasingly recognized that ideal cardiovascular health cannot be achieved by just controlling ASCVD risk factors, but also requires the active promotion of factors associated with health.3 Thus, the potential virtues of an alternative prevention paradigm - focused on cardiovascular wellness – have recently come into focus.4 This paradigm emphasizes the identification and promotion of modifiable behavioral and psychosocial factors that improve well-being and help to prevent or delay the onset of clinical disease.5,6 For example, the American Heart Association (AHA) has introduced the life’s simple 7 (LS7) score to facilitate this effort.3 While reducing illness and promoting wellness are complementary activities, too often health care providers concentrate on the former without giving due attention to the latter.4,7

Adults with advanced subclinical coronary atherosclerosis are at especially high risk for ASCVD events and are often highly motivated to improve their cardiovascular health.8 For example, primary-prevention adults without prior clinical ASCVD but with coronary artery calcium (CAC) >100 Agatston Units have event rates similar to secondary-prevention adults who have previously experienced an ASCVD event.9 Indeed, analyses from observational cohorts, including the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA),10 the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study,11 and the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study,12 have consistently demonstrated that CAC is one of the strongest known predictors of incident ASCVD and death, and provides additional prognostic information over and above traditional risk factors.

However, most adults with elevated CAC do not develop clinical ASCVD over near-to medium-term follow-up and little is known about factors associated with the absence of incident events among these individuals. These factors appear to be inversely correlated with prevalence of CAC at baseline.13 Identifying such health factors may elucidate targets that can be promoted in order to foster ideal cardiovascular health in this vulnerable population. This knowledge may also help healthcare providers counsel adults with elevated CAC on how to maintain cardiovascular wellness and avoid or delay clinical disease.

We therefore examined whether health factors are associated with lower risk and delay in onset of ASCVD or mortality among persons with elevated CAC at baseline. In accordance with the emerging concept of ideal cardiovascular health,3 the factors examined encompass self-reported behaviors and psychosocial variables, as well as measured physiologic variables.

Methods

Study Participants

MESA is a community-based cohort study of the prevalence, correlates, and progression of subclinical and clinical ASCVD. Details of the MESA study design and objectives are reported elsewhere.14 Briefly, 6814 participants between the ages of 45 to 84 free of clinical ASCVD at baseline were enrolled between 2000 and 2002 (visit 1) at 6 U.S. field centers (Baltimore, Maryland; Chicago, Illinois; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Los Angeles, California; New York, New York; and St. Paul, Minnesota). Four follow-up visits were conducted in 2002 to 2004, 2004 to 2006, 2005 to 2007, and 2010 to 2012. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at each center and all participants provided written informed consent.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Our primary analytic sample included MESA participants with significant subclinical atherosclerosis, defined as CAC >100 at baseline.9 We excluded individuals with missing information on events (n=3).

Coronary Artery Calcium Measurement

CAC was assessed at baseline using either electron-beam CT (at the Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York centers) or multidetector CT (at the Baltimore, Forsyth County, and St. Paul centers). Each participant was scanned twice and all images were interpreted at a single CT reading center (the LA Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor–UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA).13 The mean CAC score of the two scans was used. Intraobserver and interobserver agreement were excellent (kappa statistics, 0.93 and 0.90, respectively), and the intraclass correlation coefficient for the Agatston score was 0.99.10

Study Outcomes

The co-primary outcomes for this analysis were all-cause mortality and hard ASCVD, which included myocardial infarction, resuscitated cardiac arrest, CHD death, stroke, or stroke death. Secondary outcomes included all-cause ASCVD events, defined as hard ASCVD events in addition to definite angina, probable angina if followed by revascularization, other atherosclerotic death, or other CVD death. A full description of the adjudication process of events is described elsewhere.14

Measurement and Definition of Health Factors

At the baseline examination, self-reported information was collected pertaining to demographics, marital status, medication use, family history, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and sleep quality using standard and well-validated questionnaires.14

Self-Reported Behavioral Health Factors

Healthy smoking behavior was defined as absence of current cigarette smoking.3 Healthy sleep pattern was defined as having <1 day of restless sleep in the past week.15

Diet was assessed using a 120-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ, with missing variables imputed using sequential chained regression, see online appendix). FFQ data were categorized based on a previously validated score quantifying adherence to the Mediterranean-style diet.16 This resulted in a summary score ranging from 0 (poor adherence) to 11 (maximum adherence). Healthy diet was defined as having a Mediterranean-style diet score in the upper 25% of the cohort distribution.

The MESA Typical Week Physical Activity Survey (TWPAS) was designed to identify the time spent in, and frequency of, various physical activities during a typical week in the past month.16 Healthy physical activity was defined as being in the upper 25% of minutes/week of moderate/vigorous physical activity of the cohort distribution.

Self-Reported Psychosocial Health factors

Other factors of potential interest to cardiovascular health include psychosocial variables such as emotional support, depression, and chronic stress burden.18–21 Emotional support was assessed using the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory, which consists of 6 questions pertaining to the availability of emotional support. Scores range from 6 to 30, and adequate emotional support was defined as a score of ≥25.22 The presence of depressive symptoms was recorded using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Scores range from 0 to 60, and absence of depression was defined as a CES-D score <16.23 Chronic stress burden was assessed using the chronic burden scale, which measures ongoing difficulty in 5 life domains including personal health, health of a close contact, job, finances, and relationships lasting more than 6 months. Scores range from 0 to 5, and absence of chronic stress burden was defined as a score of 0.24

Measured Health Factors

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as measured weight (kg) divided by measured height squared (m2). Healthy BMI was defined as 18.5–24.9 kg/m2. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP respectively) were measured 3 times using an automated sphygmomanometer (Dinamap, Critikon, Tampa, FL), and the mean of the last 2 measurements was used. Healthy blood pressure was defined as a SBP <120 mmHg and a DBP <80 mmHg. A central laboratory (University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA) measured concentrations of total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, and plasma glucose, after a 12-hour fast. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the Friedewald equation. Healthy LDL-cholesterol was defined as LDL-C <70 mg/dL. Healthy glucose was defined as <100 mg/dL. Healthy HDL-cholesterol was defined as HDL-C >40 mg/dL for men and >50 mg/dL for women.

Other Covariates

Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg, or DBP ≥90 mmHg, or anti-hypertensive medication use. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting glucose of ≥7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL) or use of hypoglycemic medication (oral agents and/or insulin). Family history of CHD was defined in MESA as the presence of a fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary angioplasty, or coronary-artery bypass surgery in any immediate family member (parent, sibling, or child). Medication use was updated at each MESA visit following baseline (visits 2 through 5).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarized using means (standard deviation [SD]) or medians (interquartile range [IQR]) depending on normality of data for continuous variables, and using counts (percentage) for discrete variables. We used chi-square tests for discrete variables and t-tests or Kruskal Wallis test for continuous variables, as appropriate, to test for differences between participants with or without hard ASCVD events over follow-up.

To study the inverse association between health factors and incident ASCVD and mortality, we constructed multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models. The proportionality assumption was confirmed using log-log plots. Model 1 was adjusted for demographic variables (age, sex, and race/ethnicity). Model 2 was adjusted for covariates in model 1 plus MESA site, education, occupational status, income, marital status, family history of CHD, presence of diabetes mellitus, presence of hypertension and, for medications, time-varying use of statin, aspirin, glucose-lowering and antihypertensive therapies. To evaluate for possible effect measure modification by sex or race/ethnicity, we performed multiplicative interaction testing with each health factor separately in our primary analytic sample of participants with baseline CAC >100. Similarly we assessed for effect modification by CAC (≤100 vs. >100) in the association of health factors and outcomes in the overall MESA study population. Analyses of diet were additionally adjusted for total caloric intake (kcals/day) to account for the known underreporting in FFQ data,25 and further excluded participants with implausible data defined as total caloric intake <600 kcals/day or >6000 kcals/day (n= 147).

To model the cumulative effect of these health factors, we assigned each MESA participant a score of 1 for the presence of each of the above health factors, so as to derive a total “health factor” score by summing all 12 components (range 0 to 12). We also calculated the LS7 score for each participant3, using definitions published by the AHA (Supplementary Table 1). Then, to evaluate for a graded (“dose-response”) relationship between number of health factors and risk of events, unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves by tertile of health factor score for incident hard ASCVD events and mortality were drawn. Tertiles included 0 to 4, 5 to 6, and 7 to 12 health factors. Hazard ratios of events per 1 unit increase of these scores were also calculated, adjusting for covariates in Model 2.

In a secondary analysis we used an accelerated failure-time model to examine whether the health factors evaluated above were associated with event-free time gained among those MESA participants who did experience incident ASCVD or death. The accelerated failure time model estimates a time ratio whereby if a factor helps to delay the occurrence of events, the time ratio will be >1. For instance, a time ratio of 1.5 means that, among those who have an event, it takes on average 50% longer for an event to occur in persons with the health factor compared to those without.26

To test the robustness of our results we conducted the following sensitivity analyses; 1) we defined healthy blood pressure, glucose, and lipid levels using values achieved without medication use and based our definition of healthy diet and physical activity on AHA LS7 criteria; 2) we defined advanced subclinical atherosclerosis using different thresholds (CAC >75th percentile for age, sex, and race/ethnicity) (N=1667), and CAC >400 (N=675); 3) we directly modeled the outcome of being ‘event-free at administrative censoring’ for both ASCVD and death using logistic regression models with assumption of no confounding by follow up time; and 4) we accounted for competing risk of non-ASCVD mortality using Fine and Gray models evaluating ASCVD outcomes.

A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Study Cohort

The study population consisted of 1,601 MESA participants. The mean (±SD) age was 69 (±9) years, 64% were males, 49% were White, 22% African American, 18% Hispanic, and 10% Chinese. The median (IQR: 25th–75th percentile) baseline CAC was 332 (177–677) Agatston units. Baseline characteristics, overall and according to presence of incident hard ASCVD events during follow-up, are summarized in Table 1. Compared to individuals who developed incident ASCVD events, those who remained free of ASCVD at end of follow-up were on average younger, less likely to be hypertensive, diabetic, and smoke cigarettes. They also tended to engage in more moderate/vigorous physical activity, and had higher HDL-C (all p <0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population with CAC >100 Agatston units, stratified by presence or absence of incident hard ASCVD events

| Overall (N=1601) |

Absence of hard ASCVD event during follow-up (N=1325) |

Presence of hard ASCVD event during follow-up (N=276) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 69 (9) | 69 (9) | 71 (9) | 0.0003 |

| Men, % | 1027 (64) | 843 (64) | 184 (67) | 0.34 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | 0.21 | |||

| White | 792 (49) | 662 (50) | 130 (47) | |

| Chinese | 168 (10) | 146 (11) | 22 (8) | |

| African American | 357 (22) | 290 (22) | 67 (24) | |

| Hispanic | 284 (18) | 227 (17) | 57 (21) | |

| Coronary artery calcium score, Agatston units* | 332 (177–677) | 316 (170–633) | 375 (206–850) | 0.0003 |

| Hypertension, % | 979 (61) | 787 (59) | 189 (68) | 0.005 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 298 (19) | 229 (17) | 69 (25) | 0.003 |

| Graduate degree or above, % | 553 (35) | 471 (36) | 82 (30) | 0.06 |

| Income ≥ $50,000, % | 550(34) | 471 (36) | 79 (29) | 0.03 |

| Married, % | 966 (60) | 812 (61) | 154 (56) | 0.10 |

| Statin use, % | 359 (22) | 299 (23) | 60 (22) | 0.76 |

| Aspirin use, % | 481 (31) | 397 (31) | 84 (32) | 0.79 |

| Antihypertensive medication use, % | 824 (51) | 673 (51) | 151 (55) | 0.24 |

| Glucose lowering medication use, % | 244 (15) | 178 (13) | 66 (24) | <0.001 |

| Family History of CHD, % | 777(52) | 638 (52) | 139 (55) | 0.31 |

| Current smoking, % | 199 (12) | 159 (12) | 40 (14) | 0.02 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.3 (5.2) | 28.3 (5.2) | 28.4 (5.0) | 0.85 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 133 (22) | 133 (22) | 137 (23) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 73 (10) | 73 (10) | 73 (11) | 0.37 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 103 (38) | 102 (32) | 106 (40) | 0.03 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 118 (32) | 118 (32) | 116 (30) | 0.46 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 49 (15) | 50 (15) | 47 (14) | 0.02 |

| Moderate or vigorous physical activity, mins/week* | 1005 (510–1860) | 1035 (540–1890) | 840 (413–1763) | 0.04 |

| Mediterranean diet score* | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | 0.68 |

| Restless sleep (≥ 1 d/w), % | 663 (42) | 550 (42) | 113 (41) | 0.75 |

| CESD score* | 5 (2–10) | 5 (2–10) | 6 (2–11) | 0.07 |

| Chronic stress burden score =0, % | 663 (41) | 565 (43) | 98 (36) | 0.03 |

| ENRICHD score* | 26 (22–29) | 26 (22–29) | 25 (21–29) | 0.41 |

Continuous variables presented as mean (standard deviation) or median (interquartile range)*; categorical variables presented as count (percentage)

P-value calculated using t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables

Association of Health factors with Incident ASCVD and Mortality

After a median (IQR) follow-up of 12.1 (11.5–12.7) years, 276 individuals with baseline CAC >100 experienced hard ASCVD events (incidence rate = 17.7 per 1000 person-years) and 443 died (mortality rate = 25.4 per 1000 person-years). To provide perspective on the lower absolute and relative risk of events associated with each health factor (compared to the absence of this health factor), incidence rates and hazard ratios are reported in Table 2. After multivariable adjustment, absence of current smoking, healthy HDL-C levels, and low stress burden remained statistically significant inverse predictors of ASCVD (HRs ranging from 0.58 to 0.71) (Table 2). With respect to mortality, absence of current smoking, healthy glucose, regular physical activity, and absence of chronic stress burden were inversely associated with death in the multivariable-adjusted model (HRs ranging from 0.40 to 0.77), while LDL-C <70 mg/dL appeared to be directly associated with mortality (HR=1.57) (all p<0.05) (Table 2). Emotional support, absence of depression, and, to a lesser extent, Mediterranean diet also appeared protective for mortality, though multivariable adjusted models failed to reach significance. Defining healthy physical activity and diet based on AHA LS7 criteria led to similar results.

Table 2.

Multivariable adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence interval)* for the association of health factors and either incident hard ASCVD events or mortality among individuals with CAC>100 at baseline

| Hard ASCVD Events | Death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| LIFESTYLE FACTOR | Definition of health factor | Incidence rates (per 1000 person-years) comparing individuals with health factor to those without | Demographic adjustment† | Multivariable adjustment‡ | Incidence rates (per 1000 person-years) comparing individuals with health factor to those without | Demographic adjustment† | Multivariable adjustment‡ |

| Smoking | Not currently smoking | 17.0 vs. 22.9 |

0.62 (0.41,0.93) |

0.58 (0.37,0.90) |

24.1 vs. 34.8 |

0.42 (0.31,0.56) |

0.40 (0.29,0.56) |

| BMI | 18.5–24 9 m2 | 17.0 vs. 17.9 | 0.98 (0.72,1.35) |

1.03 (0.73,1.46) |

25.1 vs. 25.5 | 0.97 (0.76,1.24) |

0.95 (0.72,1.25) |

| BP | <120/80 mmHg | 13.7 vs. 19.4 | 0.75 (0.54,1.03) |

0.85 (0.59,1.23) |

21.4 vs. 27.1 | 1.00 (0.78,1.27) |

1.21 (0.91,1.62) |

| Glucose | <100 mg/dL | 16.3 vs. 20.6 | 0.82 (0.62,1.09) |

1.09 (0.73,1.62) |

22.7 vs. 31.0 |

0.69 (0.56,0.86) |

0.69 (0.51,0.93) |

| LDL-C | <70 mg/dL | 16.4 vs. 17.7 | 0.86 (0.44,1.67) |

0.93 (0.47,1.83) |

35.7 vs. 24.9 | 1.50 (1.00,2.25) |

1.57 (1.03,2.41) |

| HDL-C | >40 mg/dL (males) or >50 mg/dL (females) | 15.1 vs. 22.2 |

0.64 (0.49,0.84) |

0.62 (0.46,0.83) |

26.5 vs. 23.5 | 1.01 (0.81,1.26) |

1.16 (0.91,1.49) |

| Physical Activity | Upper quartile of physical activity | 14.8 vs. 19.8 | 0.77 (0.58,1.02) |

0.80 (0.59,1.10) |

17.3 vs. 31.2 |

0.62 (0.50,0.78) |

0.64 (0.50,0.83) |

| Diet | Upper quartile of Mediterranean diet score | 17.0 vs. 18.1 | 0.96 (0.71,1.30) |

1.01 (0.72,1.43) |

23.4 vs. 27.3 | 0.82 (0.64,1.04) |

0.84 (0.64,1.11) |

| Sleep | <1 restless sleep/week | 17.9 vs. 17.3 | 0.92 (0.70,1.20) |

0.88 (0.65,1.18) |

24.3 vs. 26.8 | 0.92 (0.75,1.14) |

0.92 (0.73,1.16) |

| Depression | CESD score <16 | 17.0 vs. 23.5 | 0.78 (0.52,1.16) |

1.11 (0.68,1.81) |

23.9 vs. 37.3 |

0.64 (0.48,0.86) |

0.74 (0.53,1.05) |

| Chronic stress burden | Chronic stress burden scale = 0 | 14.8 vs. 19.8 |

0.69 (0.52,0.92) |

0.71 (0.52,0.96) |

22.5 vs. 27.5 |

0.77 (0.62,0.96) |

0.77 (0.61,0.98) |

| Emotional support | ENRICHD score ≥25 | 16.1 vs. 19.9 | 0.85 (0.65,1.12) |

0.92 (0.68,1.25) |

22.7 vs. 29.1 |

0.77 (0.62,0.94) |

0.85 (0.67,1.09) |

Calculated using multivariable-adjusted Cox proportional hazards models

Demographic adjusted model- adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity

Multivariable adjusted model- adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, MESA site, income, occupational status, marital status, family history of CHD, presence of diabetes, presence of hypertension, time-varying statin use, time-varying aspirin use, time-varying anti-hypertensive medication use, and time-varying glucose-lowering medication use

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Bolded items are significant (p<0.05)

For both outcomes, there were no significant interactions with sex or race/ethnicity. There was also no consistent interaction between any health factor and CAC level. Defining health factors (blood pressure, LDL-C, HDL-C, glucose) based on values among untreated participants only yielded nearly identical results except that healthy HDL-C and LDL-C <70 were no longer significantly associated with hard ASCVD and mortality respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Results for the ASCVD outcome were similar in analyses accounting for competing risk from non-cardiovascular-related death; however, availability of emotional support was also shown to have an inverse association in this model (Supplementary Table 3). Logistic regression analyses directly modeling of the outcome of being ‘event free’ for hard ASCVD and mortality were also qualitatively similar, but with absence of depression significantly associated with reduced mortality in multivariate analyses (Supplementary table 4). The corresponding hazard ratios for each of these health factors among participants with various cutoffs for elevated CAC (e.g., >400 and >75th percentile) are presented in Supplementary Tables 5 (for mortality) and 6 (for ASCVD).

Accelerated Failure-Time Models

After multivariable-adjustment, participants who were non-current smokers took on average 68% longer to develop incident ASCVD (time ratio 1.68) while the corresponding time ratios for HDL-C, and absence of chronic stress burden were 1.54 and 1.41 respectively (all p<0.05) (Table 3). For death, absence of current smoking, healthy glucose, adequate levels of physical activity, absence of depression and absence of chronic stress were all associated with a relative delay in the occurrence of this outcome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusted time ratios (95% confidence interval)* for the association of health factors and either incident hard ASCVD events or mortality among individuals with CAC>100 at baseline

| Hard ASCVD Events | Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Ratio (95% CI) | Time Ratio (95% CI) | ||||

| LIFESTYLE FACTOR | Definition of health factor | Demographic adjustment† | Multivariable adjustment‡ | Demographic adjustment† | Multivariable adjustment‡ |

| Smoking | Not currently smoking |

1.57 (1.15,2.13) |

1.68 (1.18,2.39) |

1.66 (1.42,1.93) |

1.67 (1.40,1.99) |

| BMI | 18.5–24.9 m2 | 1.02 (0.79,1.31) |

0.95 (0.71,1.27) |

1.03 (0.90,1.17) |

1.00 (0.86,1.16) |

| BP | <120/80 mmHg | 1.20 (0.93,1.55) |

> 1.02 (0.75,1.40) | 0.99 (0.87,1.12) |

0.89 (0.77,1.04) |

| Glucose | <100 mg/dL | 1.18 (0.94,1.47) |

0.91 (0.66,1.26) |

1.21 (1.08,1.35) |

1.18 (1.01,1.38) |

| LDL-C | <70 mg/dL | 1.09 (0.66,1.82) |

1.13 (0.64,1.99) |

0.82 (0.66,1.02) |

0.81 (0.64,1.03) |

| HDL-C | >40 mg/dL (males) or >50 mg/dL (females) |

1.49 (1.20,1.85) |

1.54 (1.19,1.97) |

1.00 (0.90,1.12) |

0.92 (0.80,1.04) |

| Physical Activity | Upper quartile of physical activity | 1.21 (0.96,1.51) |

1.15 (0.88,1.50) |

1.31 (1.16,1.48) |

1.31 (1.14,1.50) |

| Diet | Upper quartile of Mediterranean diet score | 1.08 (0.85,1.38) |

0.97 (0.73,1.28) |

1.16 (1.02,1.32) |

1.09 (0.95,1.26) |

| Sleep | <1 restless sleep/week | 1.00 (0.80,1.23) |

1.01 (0.79,1.29) |

1.07 (0.96,1.20) |

1.06 (0.93,1.19) |

| Depression | CESD score <16 |

1.36 (1.00,1.85) |

1.23 (0.85,1.79) |

1.33 (1.15,1.55) |

1.29 (1.08,1.53) |

| Chronic stress burden | Chronic stress burden scale = 0 |

1.30 (1.04,1.63) |

1.41 (1.09,1.83) |

1.15 (1.03,1.29) |

1.15 (1.01,1.30) |

| Emotional support | ENRICHD score ≥25 |

1.27 (1.03,1.57) |

1.23 (0.95,1.58) |

1.23 (1.10,1.37) |

1.11 (0.98,1.26) |

Calculated using multivariable-adjusted accelerated failure time models: The accelerated failure time model estimates a time ratio whereby if a factor helps to delay the occurrence of events, the time ratio will be >1

Demographic adjusted model- adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity

Multivariable adjusted model- adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, MESA site, income, occupational status, marital status, family history of CHD, presence of diabetes, presence of hypertension, baseline statin use, baseline aspirin use, baseline anti-hypertensive medication use, baseline glucose-lowering medication use

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

Bolded items are significant

Healthy Lifestyle Scores

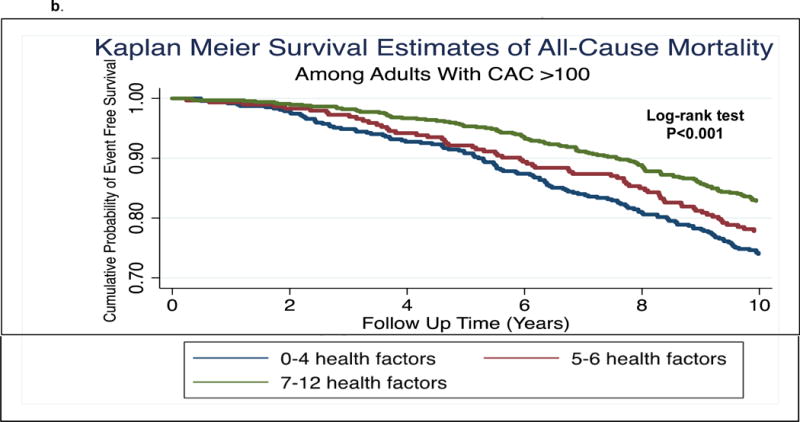

Figure 1 shows the unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves for; a) incident hard ASCVD; and b) mortality, according to tertiles of the health factor score. Each 1-unit increase in the health factor score was associated with an 11% lower risk of both hard ASCVD (95% CI 2% to 19%) and mortality (95% CI 5% to 18%). A 1-unit increase in the LS7 score was associated with a 9% lower risk of mortality (95% CI 0.01% to 17%), but results for ASCVD were not significant.

Figure 1.

a. Kaplan Meier survival estimates of incident hard ASCVD events by tertile of health factor score

b. Kaplan Meier survival estimates of incident mortality events by tertile of health factor score

Discussion

The current study demonstrates modifiable health factors that are associated with lower risk and delay in onset of ASCVD or death among individuals with subclinical atherosclerosis as determined by elevated CAC. Specifically, non-smoking, adequate physical activity, absence of chronic stress, high HDL-C levels, and normoglycemia were inversely associated with risk of hard ASCVD events and/or death. There were also favorable trends for Mediterranean diet, emotional support, and absence of depression. Importantly, there was a graded association between health factors and lower risk of events in persons with elevated CAC. These factors were also associated with a relative time-delay in disease onset among those who experienced clinical events. The novel accelerated failure time models used in this analysis are important in that they present the potential preventive impact of health factors from a vertical (i.e., how long is health maintained among persons who do have an event? [also termed compression of morbidity])27, rather than just a horizontal (i.e. do a lower proportion of persons with a given health factor have an event than those without that health factor?) perspective. Consequently, these models can illustrate the potential importance of health factors in maintaining duration of wellness, a critical societal and economic issue.

Non-smoking was the health factor most strongly associated with relative risk reduction for both ASCVD and all-cause mortality. After adjusting for time-varying statin use, optimal levels of LDL-C appeared to be associated with higher risk of mortality in our study. The cholesterol paradox has been previously described among high CVD risk individuals and persons with chronic illnesses.28 This phenomenon may reflect reverse causality. For example, the highest risk patients are often more likely to receive potent statins and thereby achieve low LDL-C. In keeping with this, among statin untreated individuals in this MESA analysis, LDL-C was no longer a significant predictor of mortality. Furthermore, healthy BMI was not a significant inverse predictor of incident outcomes in our analysis. Indeed, the predictive value of BMI in high-risk individuals with CAC >100 may be less important compared to the general population.

We believe our results have implications for the primary prevention of ASCVD in vulnerable high-risk adults with subclinical atherosclerosis. Extrapolating from the MESA study database, up to 25% of the Western adult populations could have CAC >100.10 Whether CAC imaging deserves a larger role in ASCVD prevention is outside the scope of this discussion; however, it is clear that the likelihood of future events is higher when elevated CAC is combined with uncontrolled traditional risk factors.29 Based on this, most contemporary prevention efforts in persons with elevated CAC are aimed at aggressively treating these risk factors. However, these individuals may further benefit from a strategy focused on promoting cardiovascular health by cultivating health factors. Supporting such a strategy, we demonstrate, to our knowledge for the first time, the presence of health factors that are inversely associated with events among this important population of high risk primary prevention adults, and that these health factors are independent of treated risk factors.

It is worth emphasizing that ASCVD health factors are not always simply the inverse of ASCVD risk factors. First, some health factors do not have an obvious contrasting risk factor. For instance, the converse of a Mediterranean diet is not readily and consistently identifiable (e.g., Western Diet, High-Fat Diet, High-Carbohydrate Diet, or other?). Second, some health factors (e.g., diet and exercise) could protect individuals from ASCVD via mechanisms that are different from those by which risk factors predispose to harm. Third, the presence of a well-controlled risk factor (e.g. LDL-C <100 mg/dL or SBP ≤140mmHg) may represent a lower bar than the achievement of a health factor (e.g. LDL <70 mg/dL or SBP ≤120mmHg). Fourth, the distinction between health factors and risk factors may be especially relevant in clinical practice when considered from a psychological and motivational perspective. Specifically, doctors often counsel their patients using a “risk-averse” perspective (e.g., “stop smoking or you will have a heart attack”), rather than using a “reward-seeking” one (e.g., “non-smokers live longer and healthier lives”).30

A number of salient results from this analysis are worth highlighting. First, our Kaplan-Meier survival curves demonstrate marked prognostic heterogeneity among individuals with elevated CAC, according to the presence and number of health factors assessed at the baseline visit. Second, our cumulative health factor score demonstrated an inverse relationship with risk of ASCVD and mortality, a motivating finding given the known interrelatedness of many of these factors (e.g., exercise is associated with less depression and increased psychological wellbeing).

Third, after accounting for time-varying use of preventive medication, optimal levels of blood pressure and LDL cholesterol were not independently associated with lower risk of events. The apparent lack of relative health-benefit for persons with these specific health factors could be explained by the initiation or intensification of contemporary preventive medication use (e.g., statin and anti-hypertensive drugs) among persons with sub-optimal levels of these parameters at the baseline visit (we modeled time-varying medication use in our analysis). However, precisely because our analysis adjusted for baseline and subsequent use of statin and anti-hypertensive drugs, we do not believe our results contradict the importance of treating traditional risk factors where necessary.

Taken together, these results should be of interest and assistance to providers who counsel patients with occult atherosclerosis- who are often highly motivated to improve their cardiovascular health but in whom uncertainty often exists as to the optimal prevention strategy.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. 1) This is an observational study and thus causality can be suggested, but not established. 2) Results of the CAC score were made available to participants and their physicians, which may have altered prescription patterns of preventive pharmacotherapy over follow-up that could influence cardiovascular event rates. However, we attempted to account for this by adjusting for time-varying use of such medications. Furthermore, knowledge of CAC scores may also have influenced subsequent lifestyle behavior of participants,8 thereby attenuating some of our findings. 3) The behavioral and psychosocial factors considered in this study were self-reported and may not necessarily reflect all meaningful determinants of health. Moreover, the definition of these health factors is limited based on the available information in MESA. 4) We used a derived summative healthy lifestyle scores that assigns the same weight to each health factor when in fact this may not be true. This score was designed to test the cumulative effect of known health factors on wellness and was not designed, derived, or validated for use as a prediction tool in clinical practice. 5) Finally, our study also highlights the inherent limitations of current cardiovascular epidemiology cohorts in studying wellness – a major gap in knowledge. For example, no participant-reported (or other) prospective wellness outcomes are available in the MESA dataset, requiring us to model the absence of disease as a proxy for health even though these are not one and the same.

In conclusion, modifiable health factors are associated with lower risk and delay in onset of clinical ASCVD or death among individuals with elevated CAC. Furthermore, a higher number of these health factors is associated with a lower risk of events; motivating a multifaceted and holistic approach to preventing clinical ASCVD among adults with subclinical atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Summary Statement.

The presence of high CAC does not pre-determine the development of clinical CVD and this analysis demonstrates that adults with subclinical atherosclerosis have behavioral and psychosocial options to improve their prognosis, over and above standard preventive therapies such as ASA and statin.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and grants UL1-TR-000040 and UL1- TR-001079 from the National Center for Research Resources. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary information is provided in an Online Appendix. Disclosures are provided in the submission documents.

Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00005487

References

- 1.Kannel WB, Dawber TR, Kagan A, Revotskie N, Stokes J. Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease–six year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1961;55:33–50. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Robinson JG, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PWF. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. (Journal of the American College of Cardiology).J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2935–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association’s strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labarthe DR, Kubzansky LD, Boehm JK, Lloyd-Jones DM, Berry JD, Seligman MEP. Positive Cardiovascular Health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knapper JT, Ghasemzadeh N, Khayata M, Patel SP, Quyyumi AA, Mendis S, Mensah GA, Taubert K, Sperling LS. Time to Change Our Focus: Defining, Promoting, and Impacting Cardiovascular Population Health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:960–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polonsky TS, Ning H, Daviglus ML, Liu K, Burke GL, Cushman M, Eng J, Folsom AR, Lutsey PL, Nettleton JA, Post WS, Sacco RL, Szklo M, Lloyd- Jones DM. Association of Cardiovascular Health With Subclinical Disease and Incident Events: The Multi- Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naci H, Ioannidis JPA. Evaluation of Wellness Determinants and Interventions by Citizen Scientists. JAMA. 2015;314:121–122. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozanski A, Gransar H, Shaw LJ, Kim J, Miranda-Peats L, Wong ND, Rana JS, Orakzai R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Thomson LEJ, Polk D, Min J, Budoff MJ, Berman DS. Impact of coronary artery calcium scanning on coronary risk factors and downstream testing the EISNER (Early Identification of Subclinical Atherosclerosis by Noninvasive Imaging Research) prospective randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1622–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin SS, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, Agatston A, Rivera JJ, Virani SS, Ouyang P, Jones SR, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ, Nasir K. Dyslipidemia, coronary artery calcium, and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: implications for statin therapy from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2014;129:77–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Bluemke DA, O’Leary DH, Tracy R, Watson K, Wong ND, Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–1345. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr JJ, Jacobs DR, Terry JG, Shay CM, Sidney S, Liu K, Schreiner PJ, Lewis CE, Shikany JM, Reis JP, Goff DC. Association of Coronary Artery Calcium in Adults Aged 32 to 46 Years With Incident Coronary Heart Disease and Death. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:391. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff MJ, Möhlenkamp S, McClelland R, Delaney JA, Bauer M, Jöckel HK, Kälsch H, Kronmal R, Nasir K, Lehmann N, Moebus S, Mukamal K, Erbel R, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and the Investigator Group of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study A comparison of outcomes with coronary artery calcium scanning in unselected populations: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Heinz Nixdorf RECALL study (HNR) J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 7:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bensenor IM, Goulart AC, Santos IS, Bittencourt MS, Pereira AC, Santos RD, Nasir K, Blankstein R, Lotufo PA. Association between a healthy cardiovascular risk factor profile and coronary artery calcium score: Results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) Am Heart J. 2016;174:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR, Kronmal R, Liu K, Nelson JC, O’Leary D, Saad MF, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.St-Onge M-P, Grandner MA, Brown D, Conroy MB, Jean-Louis G, Coons M, Bhatt DL, American Heart Association Obesity, Behavior Change, Diabetes, and Nutrition Committees of the Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Stroke Council Sleep Duration and Quality: Impact on Lifestyle Behaviors and Cardiometabolic Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2599–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McAuley PA, Chen H, Lee D-C, Artero EG, Bluemke DA, Burke GL. Physical activity, measures of obesity, and cardiometabolic risk: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) (NIH Public Access).J Phys Act Health. 2014;11:831–837. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen R, Gasca NC, McClelland RL, Alcántara C, Jacobs DR, Diez Roux A, Rozanski A, Shea S. Effect of Physical Activity on the Relation Between Psychosocial Factors and Cardiovascular Events (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1545–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolk R, Gami AS, Garcia-Touchard A, Somers VK. Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2005;30:625–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T, Sullivan M, Simon G, Spertus J, Russo J, Egede L, Dickson V, Howe A, Deal J, McCarty M, Mensah G, Brown D, Djärv T, Wikman A, Lagergren P, O’Neil A, Stevenson C, Williams E, Mortimer D, Oldenburg B, Sanderson K, Johansson P, Lesman-Leegte I, Lundgren J, Hillege H, Hoes A, Sanderman R, et al. Eur Heart J. Vol. 162. The Oxford University Press; 2013. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review; pp. 1860–1866. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Heart. Vol. 102. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Cardiovascular Society; 2016. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies; pp. 1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mezuk B, Diez Roux AV, Seeman T. Evaluating the buffering vs. direct effects hypotheses of emotional social support on inflammatory markers: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:1294–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zich JM, Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK. Int J Psychiatry Med. Vol. 20. SAGE Publications; 1990. Screening for Depression in Primary Care Clinics: The CES-D and the BDI; pp. 259–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bromberger JT, Matthews KA. A longitudinal study of the effects of pessimism, trait anxiety, and life stress on depressive symptoms in middle-aged women. Psychol Aging. 1996;11:207–213. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendez MA, Popkin BM, Buckland G, Schroder H, Amiano P, Barricarte A, Huerta J-M, Quiros JR, Sanchez M-J, Gonzalez CA. Am J Epidemiol. Vol. 173. Oxford University Press; 2011. Alternative Methods of Accounting for Underreporting and Overreporting When Measuring Dietary Intake-Obesity Relations; pp. 448–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei LJ. The accelerated failure time model: a useful alternative to the Cox regression model in survival analysis. Stat Med. 11:1871–1879. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen NB, Zhao L, Liu L, Daviglus M, Liu K, Fries J, Shih Y-CT, Garside D, Vu T-H, Stamler J, Lloyd-Jones DM. Favorable Cardiovascular Health, Compression of Morbidity, and Healthcare CostsClinical Perspective. Circulation. 2017;135 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang TY, Newby LK, Chen AY, Mulgund J, Roe MT, Sonel AF, Bhatt DL, DeLong ER, Ohman EM, Gibler WB, Peterson ED. Hypercholesterolemia Paradox in Relation to Mortality in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32:E22–E28. doi: 10.1002/clc.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman MG, Blaha MJ, Krumholz HM, Budoff MJ, Blankstein R, Sibley CT, Agatston A, Blumenthal RS, Nasir K. Impact of coronary artery calcium on coronary heart disease events in individuals at the extremes of traditional risk factor burden: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2232–2241. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tobler PN, O’doherty JP, Dolan RJ, Schultz W. Reward Value Coding Distinct From Risk Attitude-Related Uncertainty Coding in Human Reward Systems. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1621–1632. doi: 10.1152/jn.00745.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.