Abstract

Purpose of Review

To (1) explain what yoga is, (2) summarize published literature on the efficacy of yoga for managing cancer treatment-related toxicities, (3) provide clinical recommendations on the use of yoga for oncology professionals, and (4) suggest promising areas for future research.

Recent Findings

Based on a total of 24 phase II and one phase III clinical trials, low-intensity forms of yoga, specifically gentle hatha and restorative, are feasible, safe, and effective for treating sleep disruption, cancer-related fatigue, cognitive impairment, psychosocial distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and radiation and cancer survivors.

Summary

Clinicians should consider prescribing yoga for their patients suffering with these toxicities by referring them to qualified yoga professionals. More definitive phase III clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings and to investigate other types, doses, and delivery modes of yoga for treating cancer-related toxicities in patients and survivors.

Keywords: Yoga, Sleep disorder, Cancer-related fatigue, Cognitive impairment, Psychological distress, Musculoskeletal symptoms

Introduction

Cancer is one of the most prevalent diseases in the USA. Almost half of the population of America will be diagnosed with cancer at some point during their lifetime [1]. More than 15.5 million Americans are living with a cancer diagnosis in the USA and this number is expected to reach more than 20.3 million by 2026 [2]. Patients and survivors not only experience the illness and subsequent damage to organs and bodily systems caused by the uncontrolled growth and spread of cancer cells, but they also suffer from cancer treatment-related toxicities, such as sleep disruption, cancer-related fatigue (CRF), cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms. These toxicities occur during the time period in which patients are actively receiving treatment and may also first arise months or years after these treatments have been completed. Sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms also persist for years after treatment completion [3–9] and become worse when multiple toxicities occur at the same time; this occurs in a substantial proportion of patients and survivors [7, 10–17].

Sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms reduce cancer patients’ abilities to complete cancer treatments as prescribed and to participate in essential and valued life activities, such as work, errands, eating, walking, and family events. This compromised ability to complete activities of daily living significantly diminishes recovery, quality of life, and survival [5, 9, 18]. When severe, these toxicities significantly increase morbidity and mortality [5, 9, 18, 19]. Despite momentous advances in our capacity to diagnose cancer, treat the disease, and increase survival, effective treatments for the myriad of toxicities experienced by patients and survivors are lacking. Finding effective ways to treat cancer treatment-related toxicities is among the highest clinical research priorities at the National Cancer Institute.

Yoga is an integrative, non-pharmacologic therapy with a growing body of research suggesting it is efficacious for treating sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms among cancer patients and survivors. The purposes of this review are to (1) explain what yoga is, (2) summarize published literature on the efficacy of yoga for managing cancer treatment-related toxicities, (3) provide clinical recommendations on the use of yoga for oncology professionals, and (4) suggest promising areas for future research.

Yoga

Yoga is a mind-body therapy that includes three components: (1) physical alignment poses (asanas), breathing techniques (pranayamas), and mindful exercises (meditations) [20–25]. These three components are based on several Eastern traditions from India (e.g., Classical, Advaita Vedanta, Tantra), Tibet (e.g., Tibetan), and China (e.g., Chi Kung, Tai Chi) [20, 26, 27]. The word yoga is derived from its Sanskrit root “yuj,” which means “to yoke” or join together. In this case, yoga refers to joining the mind and the body [20, 26, 27]. There are many different styles and types of yoga. Gentle hatha and restorative yoga are two systematic approaches to yoga that are popular in the USA and increasingly accepted for use as part of traditional Western medicine [20, 23–25, 28•, 29–32]. Gentle hatha yoga focuses on physical postures and is part of many styles of yoga, including Iyengar, Anusara, Vinyasa, and others [20, 23, 24, 29, 30]. Restorative yoga focuses on full relaxation and is part of the Iyengar style of yoga [21, 22]. Gentle hatha yoga, restorative yoga, and a combination of the two may provide an effective approach for improving cancer treatment-related toxicities, such as sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms.

Yoga for Treating Sleep Disruption

Sleep disruption is among the most distressing adverse effects experienced by cancer patients and survivors. Thirty to 90% of cancer patients and survivors report sleep disruption during and after the completion of cancer treatments [33–38]. We identified ten clinical trials that tested the effects of yoga on sleep disruption in cancer patients and survivors [21, 26, 28•, 39–45]. Three trials enrolled cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy [42, 43, 45], five trials enrolled survivors who had completed these primary treatments but may have still been receiving hormonal or biologic therapies [28•, 39–41, 44], and two trials enrolled both patients with ongoing cancer treatments and cancer survivors [21, 26]. These trials investigated a variety of yoga prescriptions that varied in type of yoga, duration of yoga sessions, intensity of yoga, frequency of yoga, and overall length of the yoga intervention [21, 26, 28•, 39–45]. The types of yoga included gentle hatha, restorative, Iyengar, and Tibetan. The duration of each guided group yoga session ranged from 60 to 120 min. The intensity of the yoga sessions ranged from low to moderate. The frequency of yoga practice ranged from one to five times per week. The overall length of the yoga intervention ranged from 4 weeks to more than 6 months. Seven studies compared yoga to a standard care control [21, 26, 28•, 40, 41, 43, 44], one to a stretching control group [42], another one to a support therapy control condition (45), and the other to a health education [39]. The sample population in these trials ranged from 31 to 410 participants. All clinical trials were conducted in adult patients with cancer and/or survivors.

Cohen et al. conducted the first clinical trial using the Tibetan yoga, which incorporated low-intensity poses, breathing techniques, and mindfulness exercises with lymphoma patients experiencing sleep disruption. Results of the trial showed that yoga participants had better subjective sleep quality, faster sleep latency, longer sleep duration, and less use of sleep medications compared with patients in the standard care control group [26]. Bower et al. [39] was the first to blind yoga participants to the study hypotheses and use a time and attention control when testing the efficacy of yoga for treating sleep disruption. Mustian et al. conducted the only phase III multicenter trial testing the effectiveness of yoga for treating sleep disruption in cancer survivors [28•]. In addition, the study by Mustian and colleagues is one of the only studies to use both validated patient-reported outcome measures and objective measures, via actigraphy, of sleep. The trial compared a standardized yoga intervention (YOCAS©® 4 weeks, twice a week, 75 min/session; gentle hatha and restorative yoga) to a standard care control condition among 410 patients with cancer from 12 National Cancer Institute Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) community oncology practices throughout the USA. Yoga participants had statistically significant improvements in wake after sleep onset, sleep efficiency, self-reported sleep measures, and sleep medication usage compared to the controls [28•].

Overall, the results of these clinical trials are very encouraging with seven trials reporting significant sleep-related benefits from yoga [21, 26, 28•, 41, 42, 44, 45] and three trials reporting inconsistent null findings [39, 40, 43]. Taken together, these studies suggest that gentle hatha, restorative, and Tibetan yoga, performed in 60- to 120-min sessions, at a low to moderate intensity, one to three times per week over a period of 4 to 10 weeks may be efficacious for treating sleep disruption in cancer patients and survivors.

Yoga for Treating Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF)

CRF is one of the most noxious toxicities reported by patients and survivors [7, 9, 17, 46–48]. CRF occurs in 25–99% of patients during and after cancer treatments [7, 9, 17, 46–48]. We identified 16 randomized clinical trials that examined the effect of yoga on CRF [21, 26, 39, 41, 43–45, 49, 50•, 51–56, 57•]. Four trials tested the effects of yoga on CRF among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy [43, 45, 51, 56]. Ten trials investigated the efficacy of yoga for treating CRF among survivors post-chemotherapy and/or post-radiation therapy [39, 41, 44, 49, 50•, 52–55, 57•]. Two studies recruited both cancer patients and survivors [21, 26]. These trials were diverse in regard to the type, duration, intensity, frequency, and intervention length of yoga. Most yoga interventions used hatha or Iyengar styles of yoga and included physical postures, breathing exercises, and meditation in group format. However, one study used a home-based self-guided yoga format [53] and one study included both facility- and home-based yoga formats [55]. Yoga session durations ranged from 60 to 120 min. Intensity ranged from low to moderate. Frequency of sessions ranged from one to five classes per week. Interventions ranged in length from four weeks to six months. Eight studies showed that yoga significantly reduced CRF post-intervention and/or during 1-, 3-, or 6-month follow-ups comparing to the non-yoga intervention control groups where participants followed their standard cancer care only [41, 44, 49, 52, 57•] or received a health education intervention [39, 45, 50•]. Another two studies compared yoga to conventional strengthening exercises [51, 53] and found both groups significantly improved in multiple domains of fatigue. Therefore, both yoga and strength exercise were considered efficacious for treating CRF. Six studies did not find a group difference for CRF [21, 26, 43, 54–56]. All studies were conducted in adult cancer patients and/or survivors. Taken together, these studies suggest that gentle hatha and Iyengar yoga performed in 60- to 120-min sessions, at a low to moderate intensity, one to three times per week over a period of four to 12 weeks may be efficacious for treating CRF in cancer patients and survivors.

Yoga for Treating Cognitive Impairment

Depending on cancer type and treatments, studies show that up to 80% of patients experience “chemobrain” during treatment and it persists in up to 35% of survivors post-treatment [58, 59]. Two randomized clinical trials studied the effects of yoga on cognitive impairment in cancer survivors post-chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy [60, 61•]. Janelsins et al. reported that the four-week YOCAS©® yoga program, which combined physical alignment postures, breathing exercise, and meditations using hatha and restorative yoga styles (75-min sessions, twice a week), significantly improved memory by 19% among yoga participants compared to only a 5% improvement in memory among standard survivorship care participants [61•]. Derry et al. reported no changes in cognitive complaints immediately post-yoga intervention (hatha yoga; 90-min sessions; twice weekly; 12 weeks); however, three months later, yoga participants reported 23% less cognitive complaints [60]. These data suggest that yoga may be effective for treating cognitive impairment among cancer patients and survivors. Specifically, gentle hatha and restorative yoga, performed in 75- to 90-min sessions, at a low to moderate intensity, twice per week over a period of 4 to 12 weeks may be efficacious for treating cognitive impairment in cancer patients and survivors.

Yoga for Treating Psychological Distress

The majority of patients with cancer experience psychological distress, characterized by depression, anxiety mood disorders, and other psychological impairments [62]. We identified 18 clinical trials that studied the effect of yoga on psychological distress [21, 26, 41, 43, 45, 49, 54–56, 63–71]. One study recruited patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer [69] and one study recruited patients with lymphoma [26]; however, the majority of the studies targeted patients with breast cancer [21, 41, 43, 45, 49, 54–56, 63–68, 70, 71]. In addition, patients in 11 clinical trials were undergoing chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy while completing the yoga intervention [43, 45, 56, 64–71] and participants in two studies included both patients with ongoing cancer treatments and survivors [21, 26]. Patients in the remaining five clinical trials were survivors who had completed surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy before enrolling in the study [41, 49, 54, 55, 63]. A diverse set of yoga styles were tested in these clinical trials, including Iyengar, hatha, restorative, and Tibetan, and included poses, breathing, and meditation. Fourteen studies delivered the yoga interventions using a group format [21, 26, 41, 43, 45, 49, 54, 56, 63, 67–71], two studies used home-based yoga program [64, 66], and two studies included both group and home-based formats [55, 65]. The duration of each yoga session ranged from 60 to 90 min. The intensity of yoga ranged from low to moderate. Yoga sessions were held one to seven times per week with yoga intervention length ranging from 3 to 12 weeks. Short-term positive effects of yoga on anxiety, depression, and other psychological distress were seen in 12 studies [21, 41, 45, 56, 64–71] and two studies [41, 64] also showed long-term positive effects on psychological distress. Six trials found no significant group differences on psychological distress [26, 43, 49, 54, 55, 63]. Taken together, these studies suggest that hatha-based yoga, performed in 60- to 90-min sessions, at a low to moderate intensity, one to seven times per week over a period of 3 to 12 weeks may be efficacious for treating psychological distress in cancer patients and survivors.

Yoga for Treating Musculoskeletal Symptoms

Only one study examined the efficacy of yoga for improving musculoskeletal symptoms in cancer survivors [72]. Peppone et al. found that after 4 weeks of YOCAS©® yoga, which combined gentle hatha and restorative yoga in two 75-min sessions per week, breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitor therapy reported significant reductions in musculoskeletal pain, muscle aches, and total physical discomfort compared to the standard cancer survivorship care group [72]. These data suggest that gentle hatha and restorative yoga, performed in 75-min sessions at a low to moderate intensity twice per week over a period of 4 weeks may be efficacious for treating musculoskeletal symptoms in cancer survivors.

Potential Biological Mechanisms

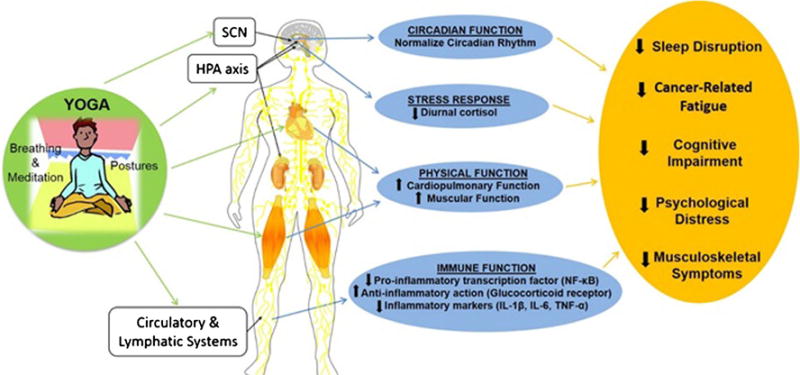

Our research group developed an integrated behavioral and biological systems theoretical model for conceptualizing and studying the effects of yoga on cancer treatment-related toxicities (see Fig. 1). Our theory is that cancer and its treatments directly and negatively influence the circadian rhythm, physical function (i.e., cardiopulmonary and muscular), the stress response (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function), and immune function; in turn, diminished function in these systems leads to CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms. Yoga is capable of positively influencing each of these systems and improving circadian rhythm, physical function, the stress response, and immune function and, consequently, reducing sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms among cancer patients and survivors.

Fig. 1.

The theoretical model of behavioral and biological systems affected by yoga intervention on cancer treatment-related toxicities

Few clinical trials have been designed to test the effects of the intervention on the plausible biological mechanisms by which yoga may improve cancer treatment-related toxicities. Several studies showed the influence of yoga on inflammation [50•, 57•, 60, 73, 74] and diurnal cortisol rhythms [49, 50•, 67]. For examples, Bower et al. [50•] showed that breast cancer survivors who participated in 12 weeks of Iyengar yoga exhibited reduced activity of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), increased activity of the anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid receptor, and reduced activity of the cAMP response element-binding (CREB) protein family transcription factors. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) activity was either decreased [57•, 74] or remained stable [50•] in the yoga group while its level was increased in the control group. Derry et al. [60] reported that 3 months after a 12-week hatha yoga intervention, breast cancer survivors had lower interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, TNF-α, CRF, and cognitive complaints than those in the standard care group. Kiecolt-Glaser et al. [57•] also showed that 12 weeks of hatha yoga help reduced plasma IL-6 and IL-1β in breast cancer survivors and the reduction of these inflammation markers was associated with reduced CRF. However, Long Parma et al. [73] found no changes in inflammatory markers among breast cancer survivors who participated in a 6-month yoga program. Banasik et al. [49] showed that breast cancer survivors had lower morning and early evening salivary cortisol levels and improved emotional well-being and fatigue scores after 8 weeks of yoga practice compared to those in the standard care group. Vadiraja et al. [67] found that 6 weeks of yoga practice reduced self-reported anxiety, depression, perceived stress, and morning salivary cortisol level in patients with breast cancer undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy. However, Bower et al. [50•] found no change in diurnal cortisol after 12 weeks of Iyengar yoga intervention in breast cancer survivors. While the data are promising, understanding of the biological mechanisms whereby yoga improves cancer treatment-related toxicities remains very limited.

Suggestions for Future Studies

Several areas need to be considered when conducting future clinical studies. First, more definitive phase III randomized clinical trials are needed. Yoga needs to be tested in a wider variety of populations to increase generalizability. For example, studies need to enroll more men, more minorities, more individuals with low socioeconomic status, more patients with advanced cancer, more patients with different types of cancer, and more older patients. Studies need to increase accrual, retention, and completion. Trials need to test a wider variety of delivery modes, such as online, DVD, home-based, and self-directed. Studies need to design and use appropriate behavioral placebo controls for comparison, as well as known efficacious treatments for comparison to yoga. Lastly and most importantly, a variety of yoga interventions in terms of the type, duration, intensity, frequency, length of intervention, and length of follow-up make it impossible to standardize the appropriate prescription and dose for yoga to provide the most benefits in managing cancer treatment-related toxicities. Many of the published studies also did not provide details regarding the actual format and components of the yoga interventions; this makes repeatability and standardization for dissemination difficult. Details on participant attendance, compliance, and attrition, as well as adverse events, need to be followed up to study how feasible of the yoga intervention to cancer populations.

Clinical Recommendations

While yoga is increasingly popular throughout the world at gyms, via self-directed books and DVDs, and at cancer center and community programs marketed toward cancer patients (e.g., “Gentle Yoga for Cancer Patients,” “Yoga for Breast Cancer Patients and Survivors,” and “Healing Yoga”), the scientific evidence regarding its efficacy for treating sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychological distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms is in nascent stages. Most yoga programs in cancer centers and in communities are not professionally regulated with respect to instructor qualifications and licensure. There is no supervision or accountability for adhering to best practices, standard of care, or evidence-based guidelines for administering yoga interventions. This lack of supervision and accountability results in significant variability as to what is offered to cancer patients in communities across the USA. For example, some yoga programs focus on very gentle, low-intensity, meditative practices (e.g., restorative, integral, Svaroopa), while others focus on moderate to vigorous practices (e.g., power, Ashtanga), or a combination of both (e.g., hatha, Iyengar, Kundalini) [75]. Some programs modify the yoga environment by using heat (e.g., Bikram) or props such as blankets, blocks, and bolsters (e.g., Iyengar) [75], resulting in classes that vary widely in structure and overall format.

The limited number of studies examining the safety and effectiveness of only limited styles and types of yoga for improving toxicities among cancer patients and survivors, lack of regulation, and wide variability of yoga formats enhances the chance that cancer patients and survivors may spend a sizeable amount of time, energy, and money participating in yoga programs that may not be safe and effective or meet their specific needs. For example, yoga in a room heated to over 100° may be contraindicated for some patients, and vigorous yoga may exacerbate, rather than alleviate, toxicities. Oncology practitioners who want to prescribe yoga to their patients are encouraged to consider this information when referring their patients to yoga programs.

Despite limitations, these studies collectively support the benefits of yoga: (1) cancer patients can safely participate in yoga while receiving chemotherapy and radiation therapy; (2) cancer survivors can safely participate in yoga after completing surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy; (3) a variety of yoga interventions for cancer patients and survivors are feasible in cancer centers and community-based yoga studios; (4) cancer patients and survivors participating in yoga programs enjoy them and find them useful; and (5) participation in low- to moderate-intensity yoga that incorporates gentle hatha, restorative, and Iyengar postures, breathing, and meditation exercises ranging from one to three sessions/week for 45–120 min per session over a period of 1 to 12 weeks may lead to improvements in sleep disruption, CRF, cognitive impairment, psychosocial distress, and musculoskeletal symptoms.

Oncology practitioners can provide important information to help cancer patients and survivors understand how they can safely begin or continue a yoga program during and after treatments [76]. Patients and survivors need to be informed by their medical providers about potential contraindications (e.g., orthopedic, cardiopulmonary, and oncologic) that might affect their yoga safety and tolerance [77]. Contraindications do not necessarily mean that cancer patients and survivors cannot participate in yoga at all; contraindications mean that specified modifications must be made so that the individual can safely and effectively participate in yoga. Referral resources can help cancer patients and survivors connect with qualified yoga instructors in their community, including those who have special training and experience working with cancer patients and survivors. If yoga instructors who have special training to work with cancer patients and survivors are not available, another option is to find and work with yoga instructors who are trained to work with other chronic medical conditions. Cancer patients and survivors will benefit from knowing what styles and types of yoga that have been tested and shown to be effective for treating specific cancer treatment-related toxicities.

Conclusions

Yoga may improve sleep disruption and lower CRF, reduce cognitive impairment, decrease psychological distress, and decrease musculoskeletal symptoms among cancer patients and survivors during and after cancer treatments. Clinicians should consider prescribing yoga for their patients suffering with these toxicities by referring them to yoga professionals who are qualified to work with cancer patients and survivors. While these data are promising, more definitive phase III clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings. Additionally, more research is needed to investigate other types, doses, and delivery modes of yoga for treating cancer-related toxicities in patients and survivors.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support NIH/NCI 1R01CA181064, NIH/NCI SUG1CA189961, NIH/NCI UG1CA189961, R25 CA102618B

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Integrative Care

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Po-Ju Lin declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Luke J. Peppone declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Michelle C. Janelsins declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Supriya G. Mohile has served as a consultant for Seattle Genetics.

Charles Kamen declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ian R. Kleckner is supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute.

Chunkit Fung declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Matthew Asare declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Calvin L. Cole declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Eva Culakova declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Karen M. Mustian declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Bishop K, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2014. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2014/, based on November 2016 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minton O, Stone P. How common is fatigue in disease-free breast cancer survivors? A systematic review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(1):5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9831-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-007-9831-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prue G, Rankin J, Allen J, Gracey J, Cramp F. Cancer-related fatigue: a critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(7):846–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrykowski MA, Donovan KA, Laronga C, Jacobsen PB. Prevalence, predictors, and characteristics of off-treatment fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5740–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cella D, Davis K, Breitbart W, Curt G. Cancer-related fatigue: prevalence of proposed diagnostic criteria in a United States sample of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(14):3385–91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.14.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Servaes P, Verhagen C, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue in cancer patients during and after treatment: prevalence, correlates and interventions. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(1):27–43. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00332-x. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00332-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Bernaards C, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Fatigue in long-term breast carcinoma survivors: a longitudinal investigation. Cancer. 2006;106(4):751–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21671. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofman M, Ryan JL, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Morrow GR. Cancer-related fatigue: the scale of the problem. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):4–10. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpenter JS, Elam JL, Ridner SH, Carney PH, Cherry GJ, Cucullu HL. Sleep, fatigue, and depressive symptoms in breast cancer survivors and matched healthy women experiencing hot flashes. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(3):591–5598. doi: 10.1188/04.onf.591-598. https://doi.org/10.1188/04.ONF.591-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stepanski EJ, Walker MS, Schwartzberg LS, Blakely LJ, Ong JC, Houts AC. The relation of trouble sleeping, depressed mood, pain, and fatigue in patients with cancer. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(2):132–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roscoe JA, Kaufman ME, Matteson-Rusby SE, Palesh OG, Ryan JL, Kohli S, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and sleep disorders. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):35–42. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-35. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(4):743–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexander S, Minton O, Andrews P, Stone P. A comparison of the characteristics of disease-free breast cancer survivors with or with-out cancer-related fatigue syndrome. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(3):384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donovan KA, Jacobsen PB. Fatigue, depression, and insomnia: evidence for a symptom cluster in cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2007;23(2):127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.01.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck SL, Dudley WN, Barsevick A. Pain, sleep disturbance, and fatigue in patients with cancer: using a mediation model to test a symptom cluster. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(3):542. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E48-E55. https://doi.org/10.1188/04.ONF.E48-E55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhnt S, Ernst J, Singer S, Ruffer JU, Kortmann RD, Stolzenburg JU, et al. Fatigue in cancer survivors—prevalence and correlates. Onkologie. 2009;32(6):312–7. doi: 10.1159/000215943. https://doi.org/10.1159/000215943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curt GA, Breitbart W, Cella D, Groopman JE, Horning SJ, Itri LM, et al. Impact of cancer-related fatigue on the lives of patients: new findings from the Fatigue Coalition. Oncologist. 2000;5(5):353–60. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.5-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NCTN disease-specific and symptom management & health related quality of life steering committees. Strategic priorities. 2015:34–8. https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/ccct/steering-committees/strategic-priorities.pdf.

- 20.Bower JE, Woolery A, Sternlieb B, Garet D. Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control. 2005;12(3):165–71. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200304. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327480501200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danhauer SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, Campbell CR, Felder L, Daley K, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: findings from a randomized pilot study. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(4):360–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.1503. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Danhauer SC, Tooze JA, Farmer DF, Campbell CR, McQuellon RP, Barrett R, et al. Restorative yoga for women with ovarian or breast cancer: findings from a pilot study. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2008;6(2):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elkins G, Fisher W, Johnson A. Mind-body therapies in integrative oncology. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2010;11(3–4):128–40. doi: 10.1007/s11864-010-0129-x. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-010-0129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: results of a national survey. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(2):44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith KB, Pukall CF. An evidence-based review of yoga as a complementary intervention for patients with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(5):465–75. doi: 10.1002/pon.1411. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen L, Warneke C, Fouladi RT, Rodriguez MA, Chaoul-Reich A. Psychological adjustment and sleep quality in a randomized trial of the effects of a Tibetan yoga intervention in patients with lymphoma. Cancer. 2004;100(10):2253–60. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20236. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirk MBB. Hatha Yoga for greater strength, flexibility, and focus. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28•.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ, Palesh OG, Chandwani K, et al. Multicenter, randomized controlled trial of yoga for sleep quality among cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3233–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707. This is the only phase III randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of yoga on sleep quality in cancer survivors. This study is also one of the only studies to use both validated subjective and objective outcome measures of sleep in cancer survivors. After 4 weeks of the YOCAS©® yoga intervention, participants reported greater improvements in sleep quality and their objective actigraphy results corroborated with the subjective outcomes. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Palesh OG, Peppone LJ, Janelsins MC, Mohile SG, et al. Exercise for the management of side effects and quality of life among cancer survivors. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8(6):325–30. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181c22324. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181c22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustian KM, Morrow GR, Carroll JK, Figueroa-Moseley CD, Jean-Pierre P, Williams GC. Integrative nonpharmacologic behavioral interventions for the management of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):52–67. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-52. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SM Hatha yoga pradipika. Poughkeepsie: Nesma Books India; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.JL Relax and renew restful yoga for stressful times. Berkeley: Publishers Group West; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ancoli-Israel S, Liu L, Marler MR, Parker BA, Jones V, Sadler GR, et al. Fatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms prior to chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(3):201–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0861-0. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0861-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berger AM, Farr LA, Kuhn BR, Fischer P, Agrawal S. Values of sleep/wake, activity/rest, circadian rhythms, and fatigue prior to adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33(4):398–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger AM, Grem JL, Visovsky C, Marunda HA, Yurkovich JM. Fatigue and other variables during adjuvant chemotherapy for colon and rectal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37(6):E359–69. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.E359-E369. https://doi.org/10.1188/10.ONF.E359-E369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palesh OG, Roscoe JA, Mustian KM, Roth T, Savard J, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Prevalence, demographics, and psychological associations of sleep disruption in patients with cancer: University of Rochester Cancer Center-Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):292–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savard J, Simard S, Blanchet J, Ivers H, Morin CM. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and risk factors for insomnia in the context of breast cancer. Sleep. 2001;24(5):583–90. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.5.583. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/24.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schultz PN, Klein MJ, Beck ML, Stava C, Sellin RV. Breast cancer: relationship between menopausal symptoms, physiologic health effects of cancer treatment and physical constraints on quality of life in long-term survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(2):204–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01030.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bower JE, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, Irwin MR, Olmstead R, et al. Yoga for persistent fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2012;118(15):3766–75. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26702. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cadmus-Bertram L, Littman AJ, Ulrich CM, Stovall R, Ceballos RM, McGregor BA, et al. Predictors of adherence to a 26-week viniyoga intervention among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19(9):751–8. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0118. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2012.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carson JW, Carson KM, Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Seewaldt VL. Yoga of awareness program for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomized trial. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(10):1301–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chandwani KD, Perkins G, Nagendra HR, Raghuram NV, Spelman A, Nagarathna R, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of yoga in women with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1058–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2752. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandwani KD, Thornton B, Perkins GH, Arun B, Raghuram NV, Nagendra HR, et al. Yoga improves quality of life and benefit finding in women undergoing radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2010;8(2):43–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johns SA, Brown LF, Beck-Coon K, Monahan PO, Tong Y, Kroenke K. Randomized controlled pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for persistently fatigued cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(8):885–93. doi: 10.1002/pon.3648. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vadiraja SH, Rao MR, Nagendra RH, Nagarathna R, Rekha M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of yoga on symptom management in breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Yoga. 2009;2(2):73–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.60048. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.60048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patrick DL, Ferketich SL, Frame PS, Harris JJ, Hendricks CB, Levin B, et al. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: symptom management in cancer: pain, depression, and fatigue, July 15–17, 2002. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(15):1110–7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henry DH, Viswanathan HN, Elkin EP, Traina S, Wade S, Cella D. Symptoms and treatment burden associated with cancer treatment: results from a cross-sectional national survey in the US. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(7):791–801. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0380-2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-007-0380-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lawrence DP, Kupelnick B, Miller K, Devine D, Lau J. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of fatigue in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:40–50. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Banasik J, Williams H, Haberman M, Blank SE, Bendel R. Effect of Iyengar yoga practice on fatigue and diurnal salivary cortisol concentration in breast cancer survivors. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23(3):135–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00573.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50•.Bower JE, Greendale G, Crosswell AD, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, et al. Yoga reduces inflammatory signaling in fatigued breast cancer survivors : arandomized controlledtrial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;43:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.01.019. This is one of the very few studies that have examined the effects of yoga on inflammatoryco processes in cancer survivors. Their findings suggested that Iyengar-based, restorative yoga intervention may alter inflmmation-related transcriptional control pathways and further influence behavorial symptoms in cancer population. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lotzke D, Wiedemann F, Rodrigues Recchia D, Ostermann T, Sattler D, Ettl J, et al. Iyengar-yoga compared to exercise as a therapeutic intervention during (neo)adjuvant therapy in women with stage I-III breast cancer: health-related quality of life, mindfulness, spirituality, life satisfaction, and cancer-related fatigue. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med: eCAM. 2016;2016:5931816. doi: 10.1155/2016/5931816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sprod LK, Fernandez ID, Janelsins MC, Peppone LJ, Atkins JN, Giguere J, et al. Effects of yoga on cancer-related fatigue and global side-effect burden in older cancer survivors. J Geriatr Oncol. 2015;6(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2014.09.184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2014.09.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stan DL, Croghan KA, Croghan IT, Jenkins SM, Sutherland SJ, Cheville AL, et al. Randomized pilot trial of yoga versus strengthening exercises in breast cancer survivors with cancer-related fatigue. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(9):4005–15. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3233-z. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3233-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Culos-Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, Hately-Aldous S. A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: physical and psychological benefits. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15(10):891–7. doi: 10.1002/pon.1021. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Littman AJ, Bertram LC, Ceballos R, Ulrich CM, Ramaprasad J, McGregor B, et al. Randomized controlled pilot trial of yoga in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: effects on quality of life and anthropometric measures. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(2):267–77. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1066-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-1066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, Harris MS, Patel SR, Hall CB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(28):4387–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57•.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bennett JM, Andridge R, Peng J, Shapiro CL, Malarkey WB, et al. Yoga’s impact on inflammation, mood, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1040–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8860. This is the first randomized controlled trial using yoga intervention on breast cancer survivors to show significant inflammatory changes. Three months after a 3-month hatha yoga intervention, fatigue, and pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF -α) were significantly lower for yoga participants compared with the control group. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janelsins MC, Kesler SR, Ahles TA, Morrow GR. Prevalence, mechanisms, and management of cancer-related cognitive impairment. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(1):102–13. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2013.864260. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2013.864260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janelsins MC, Heckler CE, Peppone LJ, Kamen C, Mustian KM, Mohile SG, et al. Cognitive complaints in survivors of breast cancer after chemotherapy compared with age-matched controls: an analysis from a nationwide, multicenter, prospective longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(5):506–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Derry HM, Jaremka LM, Bennett JM, Peng J, Andridge R, Shapiro C, et al. Yoga and self-reported cognitive problems in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;24(8):958–66. doi: 10.1002/pon.3707. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61•.Janelsins MC, Peppone LJ, Heckler CE, Kesler SR, Sprod LK, Atkins J, et al. YOCAS©® Yoga reduces self-reported memory difficulty in cancer survivors in a nationwide randomized clinical trial: investigating relationships between memory and sleep. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016;15(3):263–71. doi: 10.1177/1534735415617021. This is the first phase III randomized controlled trial suggesting that yoga can improved perceived memory function in cancer survivors. They also found that sleep quality was a partial mediator of memory difficulty in cancer survivors. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735415617021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andrykowski MA, Lykins E, Floyd A. Psychological health in cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2008;24(3):193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blank S, Kittel J, Haberman M. Active practice of Iyengar yoga as an intervention for breast cancer survivors. Int J Yoga Ther. 2005;15(1):51–9. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kovacic T, Kovacic M. Impact of relaxation training according to Yoga In Daily Life® system on perceived stress after breast cancer surgery. Integr Cancer Ther. 2011;10(1):16–26. doi: 10.1177/1534735410387418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735410387418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Gopinath KS, Srinath BS, Ravi BD, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga programme on chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16(6):462–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00739.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rao MR, Raghuram N, Nagendra HR, Gopinath KS, Srinath BS, Diwakar RB, et al. Anxiolytic effects of a yoga program in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.05.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vadiraja HS, Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Rekha M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of a yoga program on cortisol rhythm and mood states in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2009;8(1):37–46. doi: 10.1177/1534735409331456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735409331456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vadiraja HS, Rao MR, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, Rekha M, Vanitha N, et al. Effects of yoga program on quality of life and affect in early breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2009;17(5–6):274–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.06.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cramer H, Pokhrel B, Fester C, Meier B, Gass F, Lauche R, et al. A randomized controlled bicenter trial of yoga for patients with colorectal cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25(4):412–20. doi: 10.1002/pon.3927. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yagli NV, Ulger O. The effects of yoga on the quality of life and depression in elderly breast cancer patients. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2015;21(1):7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.01.002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Banerjee B, Vadiraj HS, Ram A, Rao R, Jayapal M, Gopinath KS, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga program in modulating psycho-logical stress and radiation-induced genotoxic stress in breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6(3):242–50. doi: 10.1177/1534735407306214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735407306214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peppone LJ, Janelsins MC, Kamen C, Mohile SG, Sprod LK, Gewandter JS, et al. The effect of YOCAS©® yoga for musculo-skeletal symptoms among breast cancer survivors on hormonal therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150(3):597–604. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3351-1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3351-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Long Parma D, Hughes DC, Ghosh S, Li R, Trevino-Whitaker RA, Ogden SM, et al. Effects of six months of yoga on inflammatory serum markers prognostic of recurrence risk in breast cancer survivors. SpringerPlus. 2015;4(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-0912-z. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-015-0912-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rao RM, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N, Vinay C, Chandrashekara S, Gopinath KS, et al. Influence of yoga on postoperative outcomes and wound healing in early operable breast cancer patients under-going surgery. Int J Yoga. 2008;1(1):33–41. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.36795. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.36795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ross A, Thomas S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(1):3–12. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0044. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2009.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ, Mohile S. Exercise recommendations for cancer-related fatigue, cognitive impairment, sleep problems, depression, pain, anxiety, and physical dysfunction: a review. Oncol Hematol Rev. 2012;8(2):81–8. doi: 10.17925/ohr.2012.08.2.81. https://doi.org/10.17925/OHR.2012.08.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvao DA, Pinto BM, et al. American College of Sports Medicine rounddle on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409–26. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]