Abstract

Adolescent alcohol use has been linked with a multitude of problems and a trajectory predictive of problematic use in adulthood. Thus, targeting factors that enhance early prevention efforts is vital. The current study highlights variables that mitigate or predict alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking. Using Monitoring the Future (MTF) data, multiple path analytic models revealed links between parental involvement and alcohol abstinence and initiation. Parental involvement predicted enhanced self-esteem and less self-derogation and was negatively associated with peer alcohol norms for each MTF grade sampled, with stronger associations for 8th and 10th graders than 12th graders. For younger groups, self-esteem predicted increased perceptions of alcohol risk and reduced drinking. Self-derogation was associated with peers’ pro-alcohol norms, which was linked to lower risk perceptions, lower personal disapproval of use, and increased drinking. Peer influence had a stronger association with consumption for 8th and 10th graders, whereas 12th graders’ drinking was related to personal factors of alcohol risk perception and disapproval. In all grades, general alcohol use had a strong connection to heavy episodic drinking within the past 2 weeks. Across-grade variations in association of parent, peer, and personal factors suggest the desirability of tailored interventions focused on specific factors for each grade level, with the overall goal of attenuating adolescent alcohol use.

Keywords: Adolescent alcohol use, Parental involvement, Self-esteem, Self-derogation, Peer norms, Targeted prevention

Underage drinking is a major public health concern, damaging those who drink, their families, and their communities. Alcohol use typically begins in adolescence, and although they drink less frequently, youth often drink more than adults when they do drink (Donovan 2004; Kosterman et al. 2000). Approximately 5000 underage drinkers die each year from alcohol-related incidents (NIAAA 2013). Adolescents who engage in heavy episodic drinking (i.e., consuming five or more alcoholic beverages in a single occasion) face augmented health repercussions, both immediate and long-term (Oesterle et al. 2004). These harms are posited to worsen with continued use as alcohol consumption during the teen years is related to risk factors (e.g., destructive relationships, substance abuse disorders in adulthood, future arrests) across development (Cairns and Cairns 1994; Donaldson et al. 2016a; Schulenberg and Maslowsky 2009), indicating alcohol’s continuing long-term effects (Patrick and Schulenberg 2011). It is important to identify protective factors for adolescents at different developmental stages to curtail harmful drinking behavior and its consequences.

Guided by problem behavior theory (PBT; Jessor and Jessor 1977), this research is designed to examine the connection of parent-related (i.e., parental involvement), peer-related (i.e., peer alcohol norms), and self-related factors (i.e., self-esteem, self-derogation) with attitudes toward alcohol (i.e., perceived risks, disapproval of use) and general reported alcohol use to predict heavy episodic drinking. Parental involvement and monitoring (Dishion and McMahon 1998; Donaldson et al. 2015; Hemovich et al. 2011; Pilgrim et al. 2006), peer alcohol norms (Mrug and McCay 2013; Patrick and Schulenberg 2010), self-esteem (Jessor and Jessor 1977), self-derogation (Edwards et al. 2014; Maslowsky et al. 2014b; McKay et al. 2012), perceived risks (Johnston 2003), and subjective disapproval (Palamar 2014) are all associated with drinking behaviors. However, research has yet to explore how these variables relate to each other in the context of adolescent alcohol use. The differential effects of these predictors at different stages of adolescence also require closer consideration. The goal of the current study is to investigate the relation of these factors with adolescent drinking to isolate the factors most beneficial to tailored prevention efforts for adolescents of varying grades (i.e., 8th, 10th, 12th) to curb the incidence of use, thus diminishing the possibility of heavy episodic drinking.

Problem Behavior Theory

PBT identifies three systems posited to enhance risk or to act as protective features to mitigate adolescent deviant behaviors. These systems include variables relating to the perceived environment system (e.g., parental involvement and support, peer norms and influence), the personality system (e.g., self-esteem, attitudinal tolerance for deviance), and the behavior system (e.g., alcohol use, abstinence). The balance of these systems indicates proneness to problem behaviors, including heavy episodic drinking. Donovan and Molina (2014) demonstrated the utility of this framework in predicting adolescent alcohol use.

Parent Factors

Research on the perceived environment system has revealed a strong inverse relationship between factors encompassing parental involvement (e.g., warmth, monitoring) and teen delinquency (Dishion and McMahon 1998; Donaldson et al. 2015; Gottfredson and Hussong 2011; Hemovich et al. 2011; Nash et al. 2005). Parental involvement, described as helping with homework, assigning chores, and limiting TV watching, appears to curb future risk behaviors. Youth who do not report such involvement are more prone to associate with deviant peers (Chassin et al. 1993), engage in risky behaviors (Hemovich et al. 2011), and use illicit substances at higher rates (Crano et al. 2008; Dever et al. 2012). In addition, parental involvement has been linked to variations in self-esteem: higher involvement relates to more self-esteem and thus lower incidence of risk behaviors (Parker and Benson 2005); conversely, lower levels have indirect negative effects on adolescents’ decisions to consume alcohol through increased self-derogation (Rundell et al. 2012).

Peer Factors

Peer norms are among the strongest influences on youth substance use (Bersamin et al. 2005; Hohman et al. 2014; Mrug and McCay 2013; Patrick and Schulenberg 2010) and are associated with other risk factors of alcohol use within the perceived environment system, such as parental involvement (Chassin et al. 1993; Donaldson et al. 2015; Hemovich et al. 2011). According to Patrick and Schulenberg (2010), adolescents who spent more time out with friends, felt pressure to drink, and had friends who got drunk were all at increased odds of engaging in heavy episodic alcohol use. Friends’ alcohol use in high school predicted both concurrent binge drinking and future trajectories of binge drinking (Schulenberg et al. 1996), whereas friends’ disapproval of alcohol in high school was strongly associated with lower rates of consumption and increased abstinence, especially in older youth (Bersamin et al. 2005; Mrug and McCay 2013). It seems probable that adolescents who already use alcohol may choose similarly imbibing friends, thereby re-inforcing their own use, whereas adolescents who abstain are apt to choose abstinent friends (Patrick et al. 2013).

Illustrating the interplay of systems in PBT, a peer-related factor—perceived peer disapproval of alcohol use—has been established as protective against drinking (Donovan 2004; Mrug and McKay 2013). It relates to the personality environment, involving one’s personal attitudes toward problematic behaviors. Both personal perceptions of alcohol-related risks and personal alcohol disapproval have been identified as effective barriers to adolescent alcohol use. Higher risk perception is associated with increased disapproval and leads to lower rates of adolescent drinking (Johnston 2003).

Self-Related Factors

Self-esteem, a personality system variable that involves positive attitudes toward oneself and feelings of self-worth (Jessor and Jessor 1977; Patrick and Schulenberg 2010), has been associated with lower levels of adolescent alcohol usage. McKay and associates (2012) found that self-esteem was negatively related to alcohol use. Conversely, lower levels of self-esteem have been associated with greater odds of heavy episodic drinking (Patrick and Schulenberg 2010). Self-esteem also is positively related to resilience, which has been linked to lower rates of substance use; the opposite is true of self-derogation, which is inversely related to resilience and associated with higher levels of substance use (Veselska et al. 2009).

Self-derogat ion, often described as depressive symptomology (Schulenberg et al. 1996), also has been associated with increased alcohol and drug use (Patrick and Schulenberg 2010), as well as generalized risky behavior (Tubman et al. 2003) and polysubstance use in adolescents (Maslowsky et al. 2014b). Depressive symptomology and self-derogation often manifest and frequently co-occur during adolescence. Edwards and associates (2014) found positive relations between elevated depressive symptoms and increases in both general and harmful use of alcohol at age 18. These findings foster the prediction that youth scoring higher in self-derogation will demonstrate increased rates of alcohol use.

Hypotheses

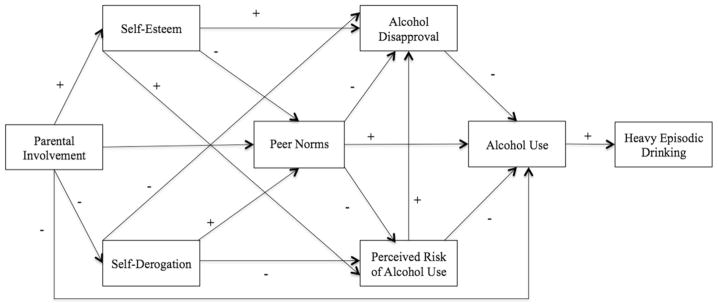

This study is designed to isolate the plausible relational pathways among factors previously associated with adolescent drinking behavior, including perceived parental involvement, self-esteem, self-derogation, peer norms, and personal perception of alcohol-related risk and alcohol-related disapproval, and to establish their linkage with alcohol use, which is posited to be predictive of recent heavy episodic drinking (see Fig. 1 for predicted model). It is hypothesized that higher levels of parental involvement will predict higher self-esteem and will be inversely related to self-derogation, peer alcohol norms, and alcohol use. In turn, self-esteem is posited to forecast less normative alcohol use and attitudes by peers, as well as increased perceived risk of use and personal disapproval. Conversely, it is predicted that self-derogation will be positively associated with peer alcohol norms and inversely related to perceptions of risk and disapproval of use. As such, it is expected that self-esteem and self-derogation are inversely related. Further, peer alcohol norms are theorized to predict lower risk perceptions, less disapproval of use, and increased alcohol use. Personal risk perception and disapproval of use are posited as protective factors: both are hypothesized to forecast less alcohol use. A final direct path is predicted from alcohol to recent (i.e., past 2 weeks) heavy episodic alcohol use.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized path analytical model for all samples

Method

Study Design

This study used the public-use data from the 2013 wave of the Monitoring the Future (MTF) dataset (Johnston et al. 2013a, b), as it was the most recent version at the time of analysis. MTF is an ongoing study of the behaviors, attitudes, and values of 8th, 10th, and 12th grade US students each year. Sample selection includes a multistage random sampling design yielding approximately 420 public and private high schools and middle schools selected each year to provide a representative cross section of US students at each grade level. 1 Measures for 8th and 10th graders differ slightly from those of 12th graders, who received more items regarding their attitudes and values as they are more fully formed by 12th grade (Johnston et al. 2012). Responses for each grade were analyzed independently in separate models, allowing examination of factors that may be more or less predictive of drinking behavior by grade.

Participants

For each grade level (8th N = 7229; 10th N = 5986; 12th N = 1570), participants were approximately evenly distributed by gender (for females by grade: 8th, 53.1 %; 10th, 51 %; 12th, 50.2 %). Samples for each grade level consisted mostly of White students (8th, 58.8 %; 10th, 66.9 %; 12th, 68.3 %), with fewer Hispanic (8th, 24.7 %; 10th, 20.4 %; 12th, 18.6 %) and African-American (8th, 16.5 %; 10th, 12.7 %; 12th, 13.1 %) students.

Measures

Parental Involvement

In line with previous research (Pilgrim et al. 2006), parental involvement was operationalized using the mean score of four items for all datasets (α=.64, .61, .62, for 8th to 12th grade, respectively). All items included the question stem: “How often do your parents (or stepparents or guardians) do the following?” Items included (a) “check on whether you have done your homework,” (b) “provide help with your homework when it is needed,” (c) “require you to do chores around the home,” and (d) “limit the amount of time you spend watching TV.” Responses were scored on 4-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (often). Higher scores indicated higher levels of involvement.

Self-Esteem

Adapted from previous research (Patrick and Schulenberg 2010), self-esteem was operationalized as the mean score of a 4-item scale (α= .83, .83, .85, for 8th to 12th grade, respectively). Items included questions such as “I have a positive attitude toward myself” and “I am a person of worth.” Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Higher scores indicated higher self-esteem.

Self-Derogation

Self-derogation, commonly termed depressive symptomology, was operationalized as the mean of four items (α= .87, .87, .88 for 8th to 12th grades, respectively) and included questions such as, “Sometimes I think I am no good at all” and “I feel I do not have much to be proud of.” Responses were measured on 5-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). Higher scores indicated increased self-derogation. This measure has been used in previous research (Maslowsky et al. 2014a).

Peer Alcohol Norms

For the 8th and 10th grade samples, peer alcohol norms were assessed using the following behavioral norm items (α=.82, .84, respectively): “How many of your friends would you estimate (1) drink alcoholic beverages (liquor, beer, wine) and (2) get drunk at least once a week?” Response options ranged from 1 (none) to 5 (all). Higher mean scores indicate more normative peer alcohol use. Different items were used for the 12th grade model, as this grade’s version of the MTF survey did not contain the behavioral peer norm items within the same form as other variables used in the model. Respondents receiving the behavioral peer norm questions did not receive parental involvement items, and vice versa. As such, the model could not be tested using behavioral peer norms. Thus, for 12th grade respondents, peer norms were instead examined using a 3-item (α= .85) composite measure of peer attitudinal norms. Items included the stem, “How do you think your close friends feel (or would feel) about you doing each of the following things?”: (1) “Taking one or two drinks nearly every day,” (2) “Taking four or five drinks nearly every day,” and (3) “Having five or more drinks once or twice each weekend.” Response options ranged from 1 (not disapprove) to 3 (strongly disapprove). For clarity in directionality comparison to the 8th and 10th grade measures of peer norms, items were reversed coded so that higher numbers indicated less disapproval.

Perception of Risk

For all datasets, perception of alcohol-related risk was assessed using a 3-item (8th and 10th grade; α= .83, .87, respectively) or 4-item scale (12th grade; α= .83). Items included the stem, “How much do you think people risk harming themselves (physically or in other ways), if they…” (1) “Try one or two drinks of an alcoholic beverage (beer, wine, liquor),” (2) “Take one or two drinks nearly every day,” (3) “Have five or more drinks once or twice each weekend,” and (4) “Take four or five drinks nearly every day (12th grade only).” Response options ranged from 1 (no risk) to 5 (great risk).

Alcohol Disapproval

Personal disapproval of alcohol use was measured for all datasets using 3-item scales (α= .91, .89, .83, for 8th to 12th graders, respectively). Questions included the stem, “Individuals differ in whether or not they disapprove of people doing certain things. Do you disapprove of people (who are 18 or older) doing each of the following?”: (1) “Taking one or two drinks nearly every day,” (2) “Taking four or five drinks nearly every day,” and (3) “Having five or more drinks once or twice each weekend.” Response options ranged from 1 (not disapprove) to 3 (strongly disapprove). Composite mean scores were computed for analysis. Higher scores indicated higher levels of personal disapproval.

Alcohol Use

To capture a broad estimate of alcohol use behavior, alcohol use was assessed using a composite score of six items (α= 0.90, 0.93, 0.94, for 8th to 12th graders, respectively). Participants were asked about the number of occasions they had consumed alcohol in their lifetimes, the past year, and the past 30 days and the number of times they had been drunk in their lifetimes, the past year, and the past 30 days. Response options included 1 (0 occasions), 2 (1–2 occasions), 3 (3–5 occasions), 4 (6–9 occasions), 5 (10–19 occasions), 6 (20–39 occasions), and 7 (40 or more occasions). See Table 2 for frequencies of reported alcohol use (1 or more occasion) or abstinence (0 occasions) for each item by grade.

Table 2.

Drinking behaviors for each grade level

| No occasions | 1 or more occasions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 8th | 10th | 12th | 8th | 10th | 12th | |

| Alcohol use | ||||||

| In the past 30 days | 90.6 % | 91.3 % | 58.7 % | 9.4 % | 8.7 % | 41.3 % |

| In the past year | 79.7 % | 81.4 % | 37.2 % | 20.3 % | 18.6 % | 62.8 % |

| In your lifetime | 74.6 % | 75.7 % | 32.6 % | 25.4 % | 24.3 % | 67.4 % |

| Number of times drunk | ||||||

| In the past 30 days | 96.9 % | 96.8 % | 71.2 % | 3.1 % | 3.2 % | 28.8 % |

| In the past year | 92.8 % | 92.6 % | 54.6 % | 7.2 % | 7.4 % | 45.4 % |

| In your lifetime | 90 % | 88.4 % | 47.2 % | 10 % | 11.6 % | 52.8 % |

| 5+ drinks in a row | ||||||

| In the past 2 weeks | 95.7 % | 87.1 % | 75.2 % | 4.3 % | 12.9 % | 24.8 % |

Heavy Episodic Drinking

In line with previous research (Patrick and Schulenberg 2010), heavy episodic drinking was measured using a single item. Participants were asked to indicate the number of times they drank five or more drinks in a row in the past 2 weeks. Response options included 1 (none), 2 (once), 3 (twice), 4 (3–5 times), 5 (6–9 times), and 6 (10+ times). Frequencies for each grade are included in Table 2.

Analytic Plan

To assess the pattern of multivariate linkages between these factors, predicted path analytic models for 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, based on the reviewed literature, were independently analyzed using MPlus version 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 2010) with robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation. In accord with analytic guidelines from MTF, a sampling weight was applied prior to analysis (Johnston et al. 2012). Path analytical models were implemented for the purpose of inferring directional associations among the constructs (Crano et al. 2015). Based on our predictions, each model had specified direct paths as detailed in Fig. 1. Beyond the direct paths, a correlation between self-esteem and self-derogation was tested in each model, as previous research reveals an inverse relationship (Patrick and Schulenberg 2010). Since both are related to one’s self-image and well-being, the correlation was included to account for their predicted inverse relationship.

As gender and race/ethnicity have been linked previously to differences in alcohol use (Bachman et al. 2011), these variables were entered as covariates in each model. Race/ethnicity was dummy coded before entry, with “White race” acting as the control group. This decision was consistent with Bachman and colleagues (2011), who reported that White/Caucasian respondents displayed significantly higher risk than did other ethnic groups for alcohol use and binge drinking.

To determine the latent factor structure of the alcohol use variables, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using an oblique rotation was performed to examine whether there existed a distinction between items regarding drinking more than a few sips of alcohol versus drinking enough to feel drunk. Results supported a single-factor solution, with all items loading sufficiently (i.e., greater than .80) onto one factor (Meyers et al. 2013).

Final models were evaluated with four robust fit indices, based on a theory of scaled adjustment recommended for correction of multivariate non-normality (Satorra and Bentler 2001). Comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis fit index (TFI) were evaluated, with values closer to 1.00 indicating appropriate model fit (Ullman 2007). The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) are sufficiently sensitive in detecting structural misspecifications and were used to judge the extent of non-fit between the hypothesized model and underlying data (MacCallum and Austin 2000). Values below .05 indicate desired close fit; higher values indicate the data do not fit the specified model. The quality of the predicted directional pathways was based on the criteria of each of the four fit indices exemplifying appropriate model fit—if any demonstrated nonfit of the data with the predicted model, the model would be rejected. Upon obtaining optimal fit indices for the final models, the significant standardized paths and correlations were examined using the recommended STDXY standardization for interpretation of path coefficients (i.e., beta weights) when using continuous variables (Muthén and Muthén 2010). In addition, R-squared values were assessed to examine the variance accounted for on outcome variables for the specified models and to calculate associated measures of effect size, Cohen’s ƒ2 (Cohen 1988).

Results

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for each model variable, are included in Table 1. Additional breakdowns of drinking behaviors pertaining to each alcohol-related item for each grade level are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for model variables

| 8th grade Mean (SD) |

10th grade Mean (SD) |

12th grade Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Parental involvement | 2.80 (.52) | 2.58 (.51) | 2.36 (.41) |

| Self-esteem | 3.99 (1.05) | 4.04 (.91) | 4.00 (.81) |

| Self-derogation | 2.16 (1.31) | 2.13 (1.21) | 2.07 (.99) |

| Peer alcohol norms | 1.75 (.81) | 2.58 (1.21) | 1.73 (.50) |

| Perceived alcohol risk | 2.88 (1.27) | 2.83 (1.10) | 3.25 (.63) |

| Alcohol disapproval | 2.32 (1.08) | 2.11 (.91) | 2.16 (.44) |

| Alcohol use | 1.33 (.58) | 1.86 (1.51) | 2.52 (.94) |

| Heavy episodic drinking | 1.10 (.21) | 1.27 (.60) | 1.50 (1.05) |

Path Analytical Models

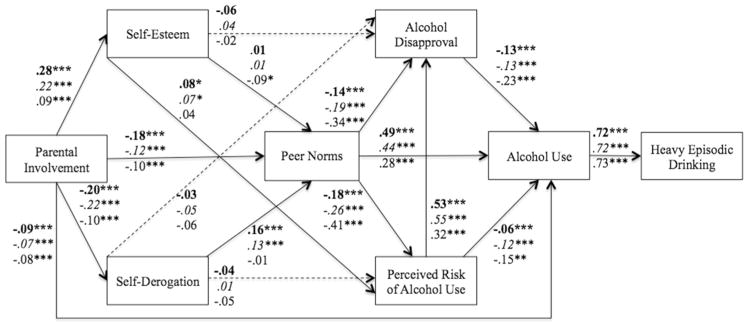

All models produced a significant model chi-square test (8th, χ2 (12) = 69.06; 10th, χ2 (12) = 27.22; 12th, χ2 (12) = 50.08; all p < .001); however, due to the large sample size, this test is sensitive to erroneous rejection of the null hypothesis (Meyers et al. 2013). The fit indices for 8th graders (CFI = .99 and TLI = .97, RMSEA = .03 [90 % CI = .02, .03], and SRMR = .02) indicated excellent model fit, as did fit indices for 10th (CFI = 1.00 and TLI = .99, RMSEA = .02 [90 % CI = .01, .02], and SRMR = .01) and 12th graders (CFI = .98 and TLI = .94, RMSEA = .05 [90 % CI = .03, .06], and SRMR = .02). Each model also yielded large effect sizes (ƒ2 greater than .35; Cohen 1988) and accounted for more than half the variance in the final outcome measure of heavy episodic drinking within the past 2 weeks (8th grade: ƒ2 = 1.08, R2 = .52; 10th grade: ƒ2 = 1.04, R2 = .51; 12th grade: ƒ2 = 1.17, R2 = .54). Standardized paths are detailed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Path analytical model for 8th, 10th, and 12th grade samples. Solid paths are statistically significant for all respondents in at least one grade. Bold numbers denote 8th grade data, italicized numbers signify 10th grade data, and regular type font indicate 12th grade data. All analyses include gender and race/ethnicity as covariates. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

As predicted, in all models, parental involvement was linked to significantly higher levels of self-esteem and operated as a buffer against self-derogation, peer alcohol norms, and alcohol use. Self and peer factors yielded smaller path coefficients for 12th graders compared to their younger counterparts. Self-esteem significantly predicted increased perception of alcohol-related risk for 8th and 10th graders, but not 12th graders. However, risk perception was linked with increased alcohol disapproval and decreased alcohol use for all grade levels. Risk perception was more strongly related to disapproval for 8th and 10th graders than for 12th graders, whereas risk perception was less strongly associated with alcohol use in 8th graders compared to 10th and 12th graders (see Fig. 2). As predicted, self-esteem and self-derogation were inversely correlated for each grade level (r = −.43, −.55, .57, for 8th to 12th graders, respectively, all p < .001).

In contrast to self-esteem, self-derogation was not predictive of either risk perception or alcohol disapproval in any model. It did, however, predict significantly higher levels of peer alcohol norms for 8th and 10th graders, but not 12th graders. Peer norms, in turn, predicted increased alcohol use for all models, but was less strongly associated for 12th graders. Further, peer norms had a direct relationship to decreased levels of both risk perception and personal alcohol disapproval and predicted increased levels of alcohol use in all models. The association of peer norms with personal risk perception and disapproval was higher for 12th graders, yet the direct link of peer influence to alcohol use was lowest for 12th graders compared to this link for 8th and 10th graders. Higher levels of both risk perception and disapproval predicted less consumption across respondents. These personal factors were more strongly related to alcohol use for the 12th grade sample, whereas peer factors more strongly predicted alcohol use among 8th and 10th graders. Alcohol use had a strong direct effect on problematic drinking. Across all models, alcohol use strongly predicted heavy episodic drinking within the past 2 weeks.

Discussion

As adolescent alcohol use is associated with myriad problems (NIAAA 2013), the main goal of this study was to augment previous research by elucidating the relation of factors linked to adolescent drinking behaviors. Informed by PBT, factors related to parents, peers, and self were examined to assess the interplay among personality, social environment, and behavioral systems. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Gottfredson and Hussong 2011; Donaldson et al. 2016a; Pilgrim et al. 2006), parental involvement had a protective effect for alcohol use for all groups: Higher levels of involvement were significantly associated with less alcohol use. Adding to current literature, the findings demonstrated the interplay between factors and highlighted parental involvement as an important first step in a path linked to either alcohol abstinence or use through factors relating to adolescents’ differential proneness to drink or to abstain from alcohol use.

Parental involvement was associated with higher self-esteem, which in turn acted as a buffer against alcohol use via significant links to the protective factors of personal perception of alcohol-related risks for 8th and 10th graders and less normative peer alcohol approval for 12th graders. Self-derogation, which was associated with lower levels of parental involvement, was connected to a path predictive of increased alcohol use. For younger adolescents (i.e., 8th and 10th graders), having a negative self-image was associated with normative alcohol consumption among one’s peers. As peer alcohol norms were inversely related to protective factors and directly predictive of increased alcohol use, this group appears to be at a heightened risk for consumption. Contrary to predictions, there were no significant direct paths between either self-esteem or self-derogation and alcohol disapproval, or self-derogation and perceived risk of alcohol use. This implies that one’s alcohol attitudes are not directly shaped by self-image, but may be indirectly influenced through the link between self-image and peer norms.

Across samples, peer norms revealed direct effects on drinking behavior, yielding larger standardized path coefficients than either parent involvement or personal attitudinal factors. Peer behavioral norms had a strong relationship with alcohol use, especially for 8th and 10th graders, as evidenced by standardized path coefficients. In all models, respondents’ risk perceptions and alcohol disapproval were associated with peer alcohol norms, with a slightly stronger link for 12th graders. Personal perceptions of risk were lower when peers’ alcohol use and attitudes were normative and approving of use. When personal perceptions of risk were low, personal disapproval also was low, as risk perception was directly linked to disapproval. This is of concern, as lower levels of both subjective risk perception and disapproval of use were related to increased alcohol use, which was associated with increased risk of heavy episodic drinking. The opposite occurred when peers’ behavioral and injunctive norms were related to abstinence. Risk perceptions have been described as major protective features (Johnston 2003). Thus, it is arguable that strengthening risk perceptions and subjective disapproval may attenuate alcohol use and thereby reduce risks of heavy episodic drinking.

Usage rates were similar for 8th and 10th graders across all alcohol items, but drastically higher for 12th graders. Thus, it is important to identify prevention factors for younger adolescents to curb this increase. The findings suggest that many students who were previously abstinent initiate use as they transition to later adolescence. Interestingly, for items related to the alcohol use measure, 12th graders’ drinking rate ranged from approximately triple to quadruple that of 10th graders; however, for the outcome of heavy episodic drinking within the past 2 weeks, rates for 12th graders were only twice as high as those of 10th graders. Although this is a major increase, it is less drastic than that of general alcohol use, indicating that adolescent alcohol use does not always lead to the greater of two evils—heavy episodic drinking.

Findings yield implications for prevention efforts that may be best suited for students at different stages of adolescence. As parenting factors revealed strong relationships with both self-image and one’s peer group for 8th and 10th graders, parent-targeted interventions would seem a worthwhile endeavor for preventing alcohol use by younger adolescents. Building on previous research (Gottfredson and Hussong 2011; Pilgrim et al. 2006; Siegel et al. 2015), interventions focused on increasing parental involvement in their child’s school and personal life, with an added emphasis on enhancing parent-child alcohol communication (Glatz and Koning 2016), could enhance youth’s self-esteem and decrease their likelihood of associating with deviant peers and reduce the incidence of alcohol initiation. Previous efforts have found that addressing parents (vs. children) in persuasive attempts resulted in less resistance and greater message acceptance by adolescents (Crano et al. 2007).

Analysis revealed a major rise in alcohol use between 10th and 12th grade students, and peer norms were directly related to alcohol use in this population. Given these results, focusing additional prevention efforts on tailoring persuasive messages to youth based on their peers’ alcohol use may be efficacious. Tailored messages are more effective than generic, one-size-fits-all communications, and have led to positive outcomes across a variety of other health behavior contexts (e.g., Enwald and Huotari 2010; Rimer and Kreuter 2006). Tailoring persuasive attempts to enhance the benefits of conforming to positive health-related peer norms and undermining conformity to peers holding deviant norms bolster prevention effects by enhancing resistance to peer normative influence (Hall and Blanton 2009).

For students in late adolescence (e.g., 12th grade), prevention efforts may be well advised to address factors related to personal alcohol attitudes, perception of risk, and personal disapproval of use, as findings reveal protective effects of these variables on alcohol use in this age group. As personal values and attitudes are more fully formed by 12th grade (Johnston et al. 2012), prevention efforts aimed at bolstering vested interest in the detrimental outcomes associated with alcohol use may prove essential in curtailing use in this group. Recent research by Donaldson et al. (2016b) provides evidence that vested interest in the harmful effects of non-medical prescription stimulant use attenuated usage intentions.

These implications should be considered in light of limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, causal inferences cannot be made. It is conceivable that alternate pathways of the predictors may have produced better model fit; however, the current predicted models resulted in optimal model fit on all three groups, which would be difficult to improve upon. Further, self-report measures may pose a threat to measurement validity (Crano et al. 2015); however, Cornelius, Leech, and Goldschmidt (2004) found that underreporting was not likely to affect results of substance use studies. The use of different measures for the constructs of peer alcohol norms and personal perception of risks for 8th and 10th versus 12th graders is another potential drawback. Although the different measures each capture aspects of the norms construct (i.e., behavioral, injunctive norms), these norms may have different influences on attitudes and behaviors.

Conclusion

Adolescent drinking behaviors are associated with many detrimental consequences (NIAAA 2013). Further, binge drinking holds great consequences for adolescents as it foretells future problems with alcohol, including increased risk of morbidity and mortality and a trajectory toward more serious alcohol-related problems (Donaldson et al. 2016a, b; Oesterle et al. 2004). As such, tailored interventions focused on factors most relevant to specific stages of adolescence are warranted for maximal preventive effectiveness. As alcohol use is commonly initiated in adolescence (Donovan 2004; Kosterman et al. 2000), a time in which peers play an increasingly influential role (Mrug and McCay 2013), the current research suggests that adolescent prevention efforts may do well to focus strongly on factors related to adolescents’ friendship groups.

Results suggest that different approaches may be warranted for younger versus older adolescents. Consistent with Siegel and colleagues (2015), parental involvement was found to play a central role in predicting factors related both to adolescents’ self-image (i.e., self-esteem, self-derogation) and peer alcohol norms and attitudes, especially among younger adolescents. Higher levels of parental involvement were associated with higher self-esteem, lower levels of self-derogation, and less positive pro-alcohol norms among one’s peers. Each of these factors was associated with respondents’ lower likelihood of drinking. Thus, parent-targeted interventions might strongly benefit this group, as would strong prevention efforts focused on resistance to deviant peer norms. As 12th graders’ alcohol use was affected by personal perceptions of harms, which is linked to subjective alcohol disapproval and decreased use, interventions bolstering one’s vested interest in the harms of drinking may prove a worthwhile endeavor.

Future research extrapolating additional factors may prove effective in curtailing use. As some of the items in the parental involvement measure may reflect an authoritarian parenting style (e.g., limiting TV watching, assigning chores), investigating the effects of authoritative (vs. authoritarian) parenting on increasing self-esteem and related protective factors would be a sensible endeavor. This would offer additional insight into parenting styles most effective at reducing adolescent risk behaviors. Further, identifying preventive factors for binge drinking—even for those who have previously consumed—would be of value in developing more effective programs of preventing major changes from occasional drinking to heavy episodic intoxication.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources This research was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Grant R01-DA032698. NIDA had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, manuscript preparation, or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Further details on the MTF purpose and study design can be found on their website, http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/purpose.html.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the IRB.

Informed Consent MTF researchers obtained informed consent from all individual participants included in their research. The current study is a secondary analysis of MTF data.

References

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Wallace JM., Jr Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between parental education and substance use among U.S. 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students: Findings from the monitoring the future project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:179–185. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin M, Paschall MJ, Flewelling RL. Ethnic differences in relationships between risk factors and adolescent binge drinking: a national study. Prevention Science. 2005;6:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-3411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD. Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pillow DR, Curran PJ, Molina BG, Barrera MR. Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: a test of three mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Leech SL, Goldschmidt L. Characteristics of persistent smoking among pregnant teenagers followed to young adulthood. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:159–169. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Patel NM. Overcoming adolescents’ resistance to anti-inhalant appeals. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:516–524. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Lac A, Hemovich V. The at-risk adolescent marijuana nonuser: Expanding the standard distinction. Prevention Science. 2008;9:129–137. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0090-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crano WD, Brewer MB, Lac A. Principles and methods of social research. 3. New York: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dever BV, Schulenberg JE, Dworkin JB, O’Malley PM, Kloska DD, Bachman JG. Predicting risk-taking with and without substance use: the effects of parental monitoring, school bonding, and sports participation. Prevention Science. 2012;13:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0288-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: a conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson CD, Nakawaki B, Crano WD. Variations in parental monitoring and predictions of adolescent prescription opioid and stimulant misuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;45:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson CD, Handren LM, Crano WD. The enduring impact of parents’ monitoring, warmth, expectancies, and alcohol use on their children’s future binge drinking and arrests: a longitudinal analysis. Prevention Science. 2016a;17:606–614. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0656-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson CD, Siegel JT, Crano WD. Nonmedical use of prescription stimulants in college students: Attitudes, intentions, and vested interest. Addictive Behaviors. 2016b;53:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Adolescent alcohol initiation: a review of psychosocial risk factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:529–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BG. Antecedent predictors of children’s initiation of sipping/tasting alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical And Experimental Research. 2014;38:2488–2495. doi: 10.1111/acer.12517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AC, Joinson C, Dick DM, Kendler KS, Macleod J, Munafò M, … Heron J. The association between depressive symptoms from early to late adolescence and later use and harmful use of alcohol. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;23:1219–1230. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0600-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enwald HPK, Huotari MLA. Preventing the obesity epidemic by second generation tailored health communication: an interdisciplinary review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12:205–223. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatz T, Koning IM. The outcomes of an alcohol prevention program on parents’ rule setting and self-efficacy: a bidirectional model. Prevention Science. 2016;7:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s11121-015-0625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson NC, Hussong AM. Parental involvement protects against self-medication behaviors during the high school transition. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1246–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DL, Blanton H. Knowing when to assume: Normative expertise as a moderator of social influence. Social Influence. 2009;4:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hemovich V, Lac A, Crano WD. Understanding early-onset drug and alcohol outcomes among youth: the role of family structure, social factors, and interpersonal perceptions of use. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16:249–267. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2010.532560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman ZP, Crano WD, Siegel JT, Alvaro EM. Attitude ambivalence, friend norms, and adolescent drug use. Prevention Science. 2014;15:65–74. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: a longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD. Alcohol and illicit drugs: the role of risk perceptions. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2003. pp. 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2011. Volume I: Secondary school students. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2012. p. 760. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: a Continuing Study of American Youth (8th- and 10th-Grade Surveys) Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2013a. [Data file]. ICPSR35166-v2. 2015-03-26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: a Continuing Study of American Youth (12th-Grade Survey) Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2013b. [Data file]. ICPSR35218-v2. 2015-03-26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Austin JT. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, Zucker RA. Influence of conduct problems and depressive symptomatology on adolescent substance use: Developmentally proximal versus distal effects. Developmental Psychology. 2014a;50:1179–1189. doi: 10.1037/a0035085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Kloska DD. Depressive symptoms, conduct problems, and risk for polysubstance use among adolescents: Results from US national surveys. Mental Health and Substance Use. 2014b;7:157–169. doi: 10.1080/17523281.2013.786750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MT, Sumnall HR, Cole JC, Percy A. Self-esteem and self-efficacy: Associations with alcohol consumption in a sample of adolescents in Northern Ireland. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy. 2012;19:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers LS, Gamst G, Guarino AJ. Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, McCay R. Parental and peer disapproval of alcohol use and its relationship to adolescent drinking: Age, gender, and racial differences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:604–614. doi: 10.1037/a0031064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nash SG, McQueen A, Bray JH. Pathways to adolescent alcohol use: Family environment, peer influence, and parental expectations. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Underage drinking. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/special-populations-co-occurring-disorders/underage-drinking.

- Oesterle S, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Adolescent heavy episodic drinking trajectories and health in young adulthood. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 2004;65:204–212. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ. Predictors of disapproval toward ‘hard drug’ use among high school seniors in the US. Prevention Science. 2014;15:725–735. doi: 10.1007/s11121-013-0436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JS, Benson MJ. Parent-adolescent relations and adolescent functioning: Self-esteem, substance abuse, and delinquency. Family Therapy. 2005;32:131–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking prevalence and predictors among national samples of American eighth- and tenth-grade students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:41–45. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. How trajectories of reasons for alcohol use relate to trajectories of binge drinking: National panel data spanning late adolescence to early adulthood. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:311–317. doi: 10.1037/a0021939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Martz ME, Maggs JL, O’Malley PM, Johnston L. Extreme binge drinking among American 12th-grade students in the United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;16:1019–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim CC, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Mediators and moderators of parental involvement on substance use: a national study of adolescents. Prevention Science. 2006;7:75–89. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimer BK, Kreuter MW. Advancing tailored health communication: a persuasion and message effects perspective. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:S184–S201. [Google Scholar]

- Rundell L, Brown CM, Cook RE. Perceived parental rejection has an indirect effect on young women’s drinking to cope. Psychology. 2012;3:935–939. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J. Taking substance use and development seriously: Developmentally distal and proximal influences on adolescent drug use. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2009;74:121–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2009.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal Of Studies On Alcohol. 1996;57:289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JT, Tan CN, Navarro MA, Alvaro EM, Crano WD. The power of the proposition: Frequency of marijuana offers, parental knowledge, and adolescent marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;148:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubman JG, Wagner EF, Langer LM. Patterns of depressive symptoms, drinking motives, and sexual behavior among substance abusing adolescents: Implications for health risk. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2003;13:37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman JB. Structural equation modeling. In: Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, editors. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2007. pp. 676–780. [Google Scholar]

- Veselska Z, Geckova AM, Orosova O, Gajdosova B, van Dijk JP, Reijneveld SA. Self-esteem and resilience: the connection with risky behavior among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]