Abstract

Objective

Infantile spasms are seizures associated with a severe epileptic encephalopathy presenting in the first 2 years of life, and optimal treatment continues to be debated. This study evaluates early and sustained response to initial treatments and addresses both clinical remission and electrographic resolution of hypsarrhythmia. Secondarily, it assesses whether response to treatment differs by etiology or developmental status.

Methods

The National Infantile Spasms Consortium established a multicenter, prospective database enrolling infants with new diagnosis of infantile spasms. Children were considered responders if there was clinical remission and resolution of hypsarrhythmia that was sustained at 3 months after first treatment initiation. Standard treatments of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), oral corticosteroids, and vigabatrin were considered individually, and all other nonstandard therapies were analyzed collectively. Developmental status and etiology were assessed. We compared response rates by treatment group using chi-square tests and multivariate logistic regression models.

Results

Two hundred thirty infants were enrolled from 22 centers. Overall, 46% of children receiving standard therapy responded, compared to only 9% who responded to nonstandard therapy (p<0.001). Fifty-five percent of infants receiving ACTH as initial treatment responded, compared to 39% for oral corticosteroids, 36% for vigabatrin, and 9% for other (p<0.001). Neither etiology nor development significantly modified the response pattern by treatment group.

Interpretation

Response rate varies by treatment choice. Standard therapies should be considered as initial treatment for infantile spasms, including those with impaired development or known structural or genetic/metabolic etiology. ACTH appeared to be more effective than other standard therapies.

West syndrome is an infantile epileptic encephalopathy, typically occurring within the first 2 years of life, with an incidence of 2 to 5 per 10,000 live births.1–4 Infantile spasms, a subtype of epileptic spasms, are the pathognomonic seizure type and are frequently associated with hypsarrhythmia on electroencephalogram (EEG) and developmental plateau or regression. The literature on preferred treatment is inconsistent and at times conflicting, suggesting multiple treatment options and dosing regimens. The most accepted treatments are adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), oral corticosteroids (OCS), and vigabatrin, although other therapies have been used.5 Despite consensus statements, recent surveys of child neurologists showed little agreement regarding best initial therapy, preferred dose, route of administration, and adjunctive medications.6,7

The effective use of ACTH and OCS was first reported in 1958.8,9 The US Food and Drug Administration dosing guidelines for ACTH recommend initial high-dose therapy (150IU/m2/day divided twice daily).10 Studies have reported response rates of 86 to 93% with high-dose ACTH,11,12 although a randomized study indicated that high-dose ACTH was not superior to low-dose ACTH (20–30IU/day).13 Some trials comparing ACTH and OCS utilized low doses (20–30IU) of ACTH, and failed to observe significant differences in response rates.14,15 The United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study (UKISS) observed similar response rates between OCS and synthetic ACTH (tetracosactide; 70% and 76%), with both superior to vigabatrin (54%).16 UKISS was not powered to compare hormone subgroups, and EEG data were not used in the assessment of the primary outcome measure. Higher dosing of prednisolone in UKISS (40–60mg/day in 3–4 divided doses) than in previous clinical trials may account for the higher response rate. Finally, case series utilizing “high-dose” OCS (initially 40–45mg/day, increased to a maximum [max] of 60mg/day)17 and “very high-dose” OCS (8mg/ kg/day, max = 60 mg/day)18 reported 2-week response rates of 67% and 63%. Trials of vigabatrin (100–148mg/ kg/day in 2 divided doses) reported a 36% remission rate.19 The response rate to vigabatrin was higher in those with tuberous sclerosis compared to other conditions (52% and 16%).19 Additional trials comparing low-dose ACTH to vigabatrin as first line therapy found better response to ACTH (74%) than vigabatrin (48%).20

Aside from those including children with tuberous sclerosis, few prospective studies have assessed etiology and development as predictors of outcome. The largest demonstrated higher infantile spasm resolution in cryptogenic cases with ACTH compared to OCS.21 A retrospective study showed no difference in response between ACTH and vigabatrin (88% and 80%) among children with unknown etiology (normal early development and brain magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]).22

Multicenter collaboration has been recommended to increase understanding of effective treatments.6 This study presents data from a large multicenter consortium evaluating early and sustained response to initial treatments and addresses both clinical remission and electrographic resolution of hypsarrhythmia. The study aims were to observe response rates by primary treatment type, and to ascertain whether children with varying etiologies or developmental status had differential responses to treatment in a prospective manner.

Patients and Methods

In 2012, The Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium developed the National Infantile Spasms Consortium (NISC) database, which is a multicenter database enrolling children prospectively. Children with new onset infantile spasms between 2 months and 2 years of age were eligible for enrollment. Clinical information was collected at the time of diagnosis and 3 months after diagnosis. Medication dosing recommendations for ACTH, OCS, and vigabatrin are provided to all NISC centers (see Table 1 for dosing recommendations) to improve homogeneity for analysis, although compliance with these recommendations was not necessary for inclusion. Treatment decisions for individual children were made by the treating clinician.

TABLE 1.

Treatment Guidelines Recommended by PERC

| Days | Dose |

|---|---|

| ACTH | |

| 1–14 | 75U/m2 IM twice daily |

| 15–17 | 30U/m2 IM in the morning |

| 18–20 | 15U/m2 IM in the morning |

| 21–23 | 10U/m2 IM in the morning |

| 24–29 | 10U/m2 IM every other morning (3 total doses) |

| Prednisolone | |

| 1–14 | l0mg oral 4 times dailya,b |

| 15–19 | l0mg oral 3 times dailya |

| 20–24 | 10mg oral 2 times daily |

| 25–29 | 10mg oral daily |

| Vigabatrinb,c | |

| 1–3 | 50mg/kg/day divided 2 times daily |

| 4–6 | l00mg/kg/day divided 2 times daily |

| >7 | 150mg/kg/day divided 2 times daily |

If there is no clinical response after day 7 (ie, no 24-hour period free of infantile spasms), the dose can be increased to 20mg 3 times daily. If done, the taper schedule from days 15–19 would be 10mg 4 times daily, then proceeding as in the table beginning on day 20.

If no clinical response by day 14, consider alternative treatment.

Side effects (eg, sedation, hypotonia) may necessitate slower titration.

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; IM = intramuscular; PERC = Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium.

The parents or guardians provided consent for all children according to center-specific institutional review board (IRB) requirements. The study was approved by all participating site IRBs. Data collected from June 2012 to July 2014 were used for this study. Children with an early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (Ohtahara syndrome/early myoclonic encephalopathy) and/or missing treatment or response data due to lack of follow-up or incomplete data entry were excluded from the analysis.

Data collected for each child included age at onset of IS, gestational age at birth, sex, presence of seizures prior to spasms, etiology, height, weight, MRI, genetic and metabolic testing, developmental assessment, presence of hypsarrhythmia at onset, infantile spasm medication, and dosage. Hypsarrhythmia was assessed at individual institutions and defined as multifocal spikes, disorganization, and >200 µV peak-to-peak in any epoch on a bipolar longitudinal montage.23 At 3 months, etiology, new MRI findings, new genetic and metabolic testing, developmental assessment, response to medication(s), and EEG findings were collected. Response to medications was recorded as response at 2 weeks from initiation of medication and response at 3 months from enrollment into study.

Standard therapy was defined as ACTH, OCS, or vigabatrin. All other medications were considered nonstandard therapy. Children initiated on simultaneous standard and nonstandard therapy (eg, ACTH and levetiracetam) had their response attributed to the standard medication. Body surface area was calculated for each child using the Haycock formula.24 Dosing for ACTH was considered high dose if >l40IU/m2/ day was used at initiation of medication. All others were categorized as low/intermediate dose. For analysis, ACTH was combined with all doses due to the small number of children receiving low/intermediate-dose ACTH.

Response to initial medication was classified into 1 of 4 response categories based on clinical infantile spasm response rate and resolution of hypsarrhythmia on EEG (when hypsarrhythmia was present at onset): early responders, late responders, relapse, and nonresponders. Early responders had resolution of clinical spasms documented in the medical record by 2 weeks and ongoing remission 3 months after the start of treatment with an EEG to confirm remission of hypsarrhythmia. Various EEGs were used, including routine, video, and prolonged EEG. Late responders had clinical remission starting after 2 weeks of treatment and had an EEG to confirm remission of hypsarrhythmia. Relapse included children who initially met response criteria and then had a return of either clinical spasms or hypsarrhythmia. All others were considered nonresponders. In our primary analyses, we defined 2 response categories as follows: responders included children who responded both early and late, and the nonresponder group included nonresponders and those who relapsed. To compare our results to other studies, in separate analyses, we defined 2-week responders as those who responded early and those who responded early but then relapsed.

Development was recorded as the clinician’s perception of overall developmental, motor, and cognitive status, with each defined as normal, mild or equivocal delay, or definite abnormality. These 3 domains were then used to create an overall assessment of development categorized as normal, mild, moderate, and severe. Children with no domain marked as abnormal were classified as having normal development. If 1 domain was marked as mild, the child was included in the mild developmental delay group. The moderate developmental delay group consisted of children with 2 or more domains marked as mild or 1 domain marked as a definite abnormality. Severe developmental delay included children with 2 or more domains that were marked as definite abnormality.

Etiology was classified into 5 primary etiologic classifications: genetic/metabolic, malformation of cortical development, prior acquired injury, other structural, and unknown. Tuberous sclerosis was classified as other structural according to International League Against Epilepsy guidelines25 and was not removed from analysis due to small numbers. For data analysis, those with unknown etiology were further categorized into normal and abnormal development. Unknown etiology with normal development was analyzed as a separate category, whereas genetic/metabolic was combined with unknown etiology and abnormal development. The latter group likely represents presumed genetic causes, but without a determined etiology in the 3-month follow-up period (either due to late diagnosis, decreased utilization of testing, or genetic influences that are non-Mendelian). Additionally, malformations of cortical development, prior injury, and other structural were categorized together as a structural cause of epilepsy.

Statistical Analysis

We compared demographic and clinical characteristics by treatment group (ACTH, OCS, vigabatrin, or other) using chi-square tests for categorical covariates and Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous covariates. To understand the association of demographic and clinical covariates with treatment response, we used chi-square tests to compare the proportions of responders in each group. Next, we fit multivariate logistic regression models to estimate crude and adjusted relative risk of responding to treatment.26 We also estimated the adjusted predicted probability of treatment response for each treatment and etiologic or developmental category of interest. Prior to selecting final models, we explored the possibility of interaction between treatment and etiology or development. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Entrance criteria were met by 282 subjects. Fifty-two were excluded for the following reasons: lack of adequate data (n = 33), lost to follow-up (n = 8), deceased (n = 6), and early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (Ohtahara syndrome/early myoclonic encephalopathy; n = 5). Two hundred thirty subjects had complete follow-up information including clinical and EEG response to individual treatments for a 3-month period. Twenty-two centers contributed data, with 1 to 43 children enrolled per center. The median (Q1, Q3) age of infantile spasm onset was 6.5 months (4.5, 8.5), and the time from spasm infantile onset to initiation of treatment was 15 days (6, 37; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics by Type of Spasm Treatment

| Characteristic | Spasm Treatment | Total, n = 230 |

pa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH, n = 97 |

Oral Corticosteroid, n = 54 |

Vigabatrin, n = 47 |

Other, n = 32 |

|||

| Sex | 0.80 | |||||

| Male | 54 (56) | 26 (48) | 24 (51) | 18 (56) | 122 (53) | |

| Race | 0.27 | |||||

| Black | 12 (14) | 8 (17) | 4 (9) | 7 (24) | 31 (15) | |

| White | 59 (66) | 34 (74) | 35 (80) | 19 (66) | 147 (71) | |

| Other | 18 (20) | 4 (9) | 5 (11) | 3 (10) | 30 (14) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.21 | |||||

| Hispanic | 17 (20) | 2 (5) | 8 (18) | 4 (15) | 31 (16) | |

| Gestational age, wk | 39 (37, 40) | 40 (38, 40) | 39 (37, 40) | 38 (33, 40) | 39 (37, 40) | 0.10 |

| Age at spasm onset, mo | 6.0 (4.5, 8.0) | 7.0 (4.5, 9.0) | 6.0 (4.5, 7.7) | 7.7 (6.0, 10.0) | 6.5 (4.5, 8.5) | 0.03 |

| First spasm to diagnosis, days | 14 (5, 32) | 10 (5, 18) | 14 (4, 73) | 18 (2, 28) | 13 (5, 31) | 0.26 |

| First spasm to treatment start, days | 16 (6, 37) | 12 (6, 21) | 21 (6, 74) | 15 (3, 47) | 15 (6, 37) | 0.13 |

| Diagnosis to treatment start, days | 1 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 2 (1, 5) | 0 (−l, 9) | 1 (0, 2) | <0.001 |

| Prior seizures | 19 (20) | 17 (32) | 19 (40) | 20 (63) | 75 (33) | <0.001 |

| History of AED use | 21 (22) | 22 (41) | 21 (45) | 19 (59) | 83 (36) | <0.001 |

| Etiologyb | <0.001 | |||||

| Genetic/metabolic | 18 (19) | 11 (20) | 13 (28) | 8 (25) | 50 (22) | |

| Prior brain injury | 17 (18) | 15 (28) | 11 (23) | 9 (28) | 52 (23) | |

| MCD/other structural | 9 (9) | 5 (9) | 16 (34) | 8 (25) | 38 (17) | |

| Unknown abnormal | 29 (30) | 16 (30) | 6 (13) | 5 (16) | 56 (24) | |

| Unknown normal | 24 (25) | 7 (13) | 1 (2) | 2 (6) | 34 (15) | |

| Developmental issues | <0.001 | |||||

| None | 31 (32) | 7 (13) | 2 (4) | 3 (10) | 43 (19) | |

| Mild | 10 (10) | 6 (11) | 4 (9) | 1 (3) | 21 (9) | |

| Moderate | 15 (16) | 9 (17) | 12 (26) | 2 (7) | 38 (17) | |

| Severe | 40 (42) | 31 (59) | 29 (62) | 25 (81) | 125 (55) | |

Values are No. (column %) or median (Ql, Q3).

Missing values: race (n = 22), ethnicity (n = 35), gestational age (n = 2), age at spasm onset (n = 5), time between first spasm and diagnosis (n = 2), time between first spasm and treatment start (n = 3), time between diagnosis and treatment start (n = 3), and development (n = 3).

Chi-square test for categorical variables, Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables.

There were 11 participants with tuberous sclerosis (included in the MCD/other structural etiology group). Eight were on vigabatrin, 1 on ACTH, and 2 received other treatment.

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; AED = antiepileptic drug; MCD = malformation of cortical development.

The first treatment choice for infantile spasms was ACTH in 42%, OCS in 23%, and vigabatrin in 20%, whereas 14% were prescribed nonstandard therapies (levetiracetam, topiramate, clobazam, valproic acid, zonisamide, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, clonazepam, and ketogenic diet). Clinicians followed NISC dosing recommendations in 80 of 96 (83%) of ACTH-treated children, 34 of 50 (68%) of OC-treated children, and 32 of 41 (78%) of those treated with vigabatrin. We did not observe any significant differences in the distribution of treatment choice based on sex, race, ethnicity, gestational age, age at infantile spasm onset, time to diagnosis, or time to treatment. However, we did observe differences in choice of treatment by other clinical characteristics. Children with a history of prior seizures or antiseizure medication use were less likely to be treated with ACTH and more likely to be treated with a nonstandard therapy (see Table 2). The etiology of infantile spasms was also associated with treatment choice, with vigabatrin prescribed more frequently to those with a structural cause. There was prescribing variation based on development at the time of presentation; children prescribed ACTH had the highest percentage of mild or no developmental issues, whereas children prescribed nonstandard therapy were most likely to have severe developmental issues (p<0.001; see Table 2).

Ninety-one of 198 (46%) children receiving standard therapy were responders with early or late clinical remission and resolution of hypsarrhythmia by EEG, whereas only 3 of 32 (9%) responded to nonstandard therapy (p<0.001). Fifty-three of 97 (55%) infants receiving ACTH as initial treatment responded, compared to 21 of 54 (39%) for OCS, 17 of 47 (36%) for vigabatrin, and 3 of 32 (9%) for other (overall p<0.001). When we compared response rate between pairs of treatments, we observed significant differences (all p< 0.01 between each standard treatment and other, nonstandard treatment). The response rate in the ACTH group was significantly higher than in the vigabatrin group (p = 0.038) and marginally higher than in the OCS group (p = 0.06). We did not observe a significant difference in response rate between OCS and vigabatrin. In 11 children with tuberous sclerosis, 8 were treated with vigabatrin, and 5 responded (62%); those treated with ACTH (n51) and nonstandard therapy (n52) did not respond. Of the 80 children who received high-dose ACTH, 46 (58%) responded, compared to 6 (38%) of the 16 who received low/intermediate-dose ACTH (p = 0.14).

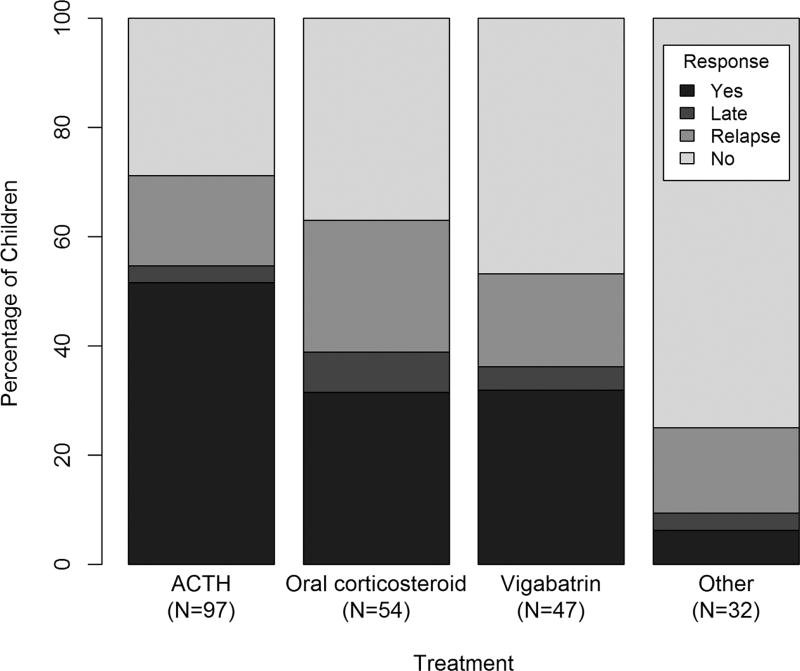

Detailed 2-week and 3-month response by treatment is shown in the Figure. We observed the greatest relapse rate in the OCS group (24%) compared to the other 3 treatment groups (18% overall), but this difference was not significant (p = 0.21). At 2 weeks, 66 of 97 (68%) on ACTH and 30 of 54 (56%) on OCS had responded (p = 0.13). The response rate to ACTH at 2 weeks was significantly higher than the rate in those on vigabatrin (23 of 47, 49%, p = 0.027) or nonstandard treatment (7 of 32, 22%, p< 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Response by treatment. ACTH5 adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Response rates were also significantly higher for those without a history of prior seizures or antiseizure medication use (Table 3). In unadjusted analysis, children with normal development or mild developmental delay had a higher response rate than children with moderate or severe delay (p = 0.025). Children with unknown etiology and normal development had a higher response rate (20 of 34, 59%) than children with genetic (40 of 106, 38%) or structural (34 of 90, 38%) etiologies, although this was not statistically significant (p = 0.07).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics by Response to First Spasm Treatment

| Characteristic | Response to Treatment | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonresponse, n = 136 |

Response, n = 94 |

||

| Sex | 0.82 | ||

| Female | 63 (58) | 45 (42) | |

| Male | 73 (60) | 49 (40) | |

| Race | 0.91 | ||

| Black | 20 (65) | 11 (36) | |

| White | 89 (61) | 58 (40) | |

| Other | 18 (60) | 12 (40) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.44 | ||

| Hispanic | 17 (55) | 14 (45) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 102 (62) | 18 (51) | |

| Gestational age | 0.60 | ||

| <37 weeks | 30 (63) | 18 (38) | |

| At least 37 weeks | 105 (58) | 75 (42) | |

| Age at spasm onset | 0.97 | ||

| <12 months | 119 (59) | 84 (41) | |

| At least 12 months | 13 (59) | 9 (41) | |

| First spasm to treatment start | 0.35 | ||

| Within 4 weeks | 93 (61) | 59 (39) | |

| >4 weeks | 41 (55) | 34 (45) | |

| Prior seizures | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 55 (73) | 20 (27) | |

| No | 81 (52) | 74 (48) | |

| History of AED use | 0.013 | ||

| Yes | 58 (70) | 25 (30) | |

| No | 78 (53) | 69 (47) | |

| Etiology | 0.070 | ||

| Genetic/metabolic/unknown abnormal | 66 (62) | 40 (38) | |

| Prior brain injury/MCD/other structural | 56 (62) | 34 (38) | |

| Unknown normal | 14 (41) | 20 (59) | |

| Developmental issues | 0.025 | ||

| None/mild | 30 (47) | 34 (53) | |

| Moderate/severe | 103 (63) | 60 (37) | |

| Treatment | <0.001 | ||

| ACTH | 44 (45) | 53 (55) | |

| Oral corticosteroid | 33 (61) | 21 (39) | |

| Vigabatrin | 30 (64) | 17 (36) | |

| Other | 29 (91) | 3 (9) | |

Values are No. (row %).

Missing values: race (n = 22), ethnicity (n = 35), gestational age (n = 2), age at spasm onset (n = 5), time between first spasm and diagnosis (n = 2), time between first spasm and treatment start (n = 3), time between diagnosis and treatment start (n = 3), and development (n = 3).

Chi-square test.

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; AED = antiepileptic drug; MCD = malformation of cortical development.

Our final multivariate logistic regression analyses consisted of 2 models, one including treatment and developmental status as covariates, the other including treatment and etiology. Model results are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Crude and adjusted relative risks of response between treatment groups and development and etiology categories are shown in Table 4. These analyses showed that after adjusting for development and etiology, choice of treatment was still a significant predictor of response. Children on standard treatments had >3 times greater probability of responding than those on nonstandard treatments, with children on ACTH >5 times as likely to respond. In models adjusting for treatment, the effects of etiology and development on response were weaker than the effects seen in the unadjusted models. The predicted probability of response to specific treatments is presented for each etiology and developmental status group (see Table 5). We did not observe modification of the overall treatment effect by either etiology or development; the predicted treatment response patterns were similar across the etiologic and developmental subgroups.

TABLE 4.

Relative Risk of Response by Treatment, Etiology, and Development

| Covariate | Crude Relative Risk (95% CI) |

Adjusteda Relative Risk(95% CI) |

Adjustedb Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | |||

| ACTH | 5.81 (4.10–9.40) | 5.50 (3.83–9.18) | 5.24 (3.59–8.70) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 4.15 (2.78–6.76) | 4.11 (2.78–6.52) | 3.88 (2.63–6.46) |

| Vigabatrin | 3.91 (2.60–6.45) | 3.92 (2.64–6.50) | 3.69 (2.55–6.18) |

| Other | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Etiology | |||

| Genetic/metabolic/unknown abnormal | Reference | Reference | — |

| Prior brain injury/MCD/other structural | 1.00 (0.69–1.43) | 1.06 (0.98–1.16) | — |

| Unknown normal | 1.56 (1.04–2.22) | 1.39 (0.89–1.99) | — |

| Development | |||

| None/mild | 1.42 (1.04–2.01) | — | 1.23 (0.86–1.72) |

| Moderate/severe | Reference | — | Reference |

Relative risks, or relative probabilities, of treatment response between groups were estimated using the method of Kleinman and Norton applied logistic regression models; confidence intervals were estimated via bootstrapping.

Model including treatment and etiology as covariates.

Model including treatment and development as covariates.

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; CI = confidence interval; MCD = malformation of cortical development.

TABLE 5.

Etiology, Development, and Treatment Effect on Response

| Characteristic | Treatment | Response to Treatment | Predicted Probability of Response (95% CI)a |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonresponse, n = 136 |

Response, n = 94 |

|||

| Etiology | ||||

|

| ||||

| Genetic/metabolic/ unknown abnormal | ACTH | 25 (53) | 22 (47) | 49% (37–62) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 15 (56) | 12 (44) | 35% (23–50) | |

| Vigabatrin | 13 (68) | 6 (34) | 33% (20–50) | |

| Other | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | 8% (3–24) | |

|

| ||||

| Prior brain injury/ MCD/other structural | ACTH | 10 (39) | 16 (62) | 55% (40–68) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | 40% (26–56) | |

| Vigabatrin | 16 (59) | 11 (41) | 38% (24–54) | |

| Other | 15 (88) | 2 (12) | 10% (3–27) | |

|

| ||||

| Unknown normal | ACTH | 9 (38) | 15 (63) | 65% (48–80) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 3 (43) | 4 (57) | 51% (30–71) | |

| Vigabatrin | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 49% (26–72) | |

| Other | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 15% (4–41) | |

| Developmental issues | ||||

|

| ||||

| None/mild | ACTH | 17 (42) | 24 (59) | 61% (47–73) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 7 (54) | 6 (46) | 47% (30–64) | |

| Vigabatrin | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 44% (26–64) | |

| Other | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 13% (4–35) | |

|

| ||||

| Moderate/severe | ACTH | 26 (47) | 29 (53) | 51% (39–63) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 25 (63) | 15 (38) | 37% (25–52) | |

| Vigabatrin | 27 (66) | 14 (34) | 35% (23–50) | |

| Other | 25 (93) | 2 (7) | 9% (3–25) | |

Values are No. (row %).

Predicted probabilities of response to treatment (expressed as a percentage) were estimated via 2 logistic regression models: (1) model containing etiology (overall p = 0.29) and treatment (p = 0.0016) as covariates, (2) model containing development (p = 0.24) and treatment (p = 0.0023) as covariates.

ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone; CI = confidence interval; MCD = malformation of cortical development.

Discussion

The National Infantile Spasms Consortium (NISC) database provides a multicenter, prospective cohort of children with newly diagnosed infantile spasms. The large prospective nature of the study allows for assessment of selection bias of treatment for a number of factors, including baseline development and etiology. The size of this multicenter study also enables greater power to distinguish outcomes. Assessing outcome at 3 months allows for a more clinically appropriate analysis of response to medication accounting for relapse rates.

The determination of efficacy by both immediate and sustained response at 3 months, in our study, allows for a more complete clinical picture regarding response to treatment. The majority of studies have assessed outcome at 2 weeks.11,12,16–20,27 Similar to other studies, we found that ACTH (all doses combined) was associated with higher early response rate than vigabatrin or OCS, although this did not reach statistical significance for OCS.11,16,20,22 At 3 months, after taking into account relapse rates, the sustained response rate in those treated with ACTH was still significantly higher compared to those treated with vigabatrin and marginally higher than those treated with OCS. The difference in outcomes particularly between ACTH and OCS may be due to the increased relapse rate that was present in the OCS group. Previous studies with shorter follow-up often did not account for relapse rates, and the only long-term follow-up studies were smaller (24 and 97 subjects each)14,15 and used variable dosing of ACTH and OCS. This may have led to an overestimation of response rate to OCS. In the current study, relapses occurred with all treatments, but were more frequent with OCS. Future study designs should account for relapse rate, as it may vary by treatment. Our data also demonstrate a higher response rate to ACTH in children with unknown etiology, which differs from a previously published study demonstrating vigabatrin as equally effective to ACTH20; this may be due to the larger size of our study and its prospective design.

Children were more likely to respond to standard therapies than nonstandard therapies. Our findings suggest the importance of using standard therapeutic agents for treatment of infantile spasms. These differences were seen for early response, 3-month response, and relapse rates. The large cohort relative to other studies and observation nature of this study allow for evaluation of a sizeable group of children on nonstandard therapy (therapies other than ACTH, OCS, and vigabatrin). This was a heterogeneous group in regard to treatment. Currently available information regarding nonstandard treatments for infantile spasms is limited to small retrospective cohorts and limited case studies. A recent study demonstrated improved rates of spasm remission after a standard treatment protocol was implemented (78.8% poststandardization compared to 30.6% prestandardization). Treatment was standardized to ACTH, OCS, or vigabatrin, and other antiseizure medications were no longer used, providing indirect evidence of poor outcomes with nonstandard medications.28 Our findings provide additional evidence of poor response to nonstandard medications. The most recent guidelines on treatments of infantile spasms from American Academy of Neurology/Child Neurology Society (AAN/CNS) state that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether other (nonstandard) therapies, including valproic acid, pyridoxine, and ketogenic diet, are effective treatments for spasms.

The etiology of spasms and the presence of moderate–severe delays at onset were not as strongly associated with treatment response as the choice of treatment itself. There were differences in prescriber choice of initial therapy based on patient development and etiology. Children with mild or no developmental issues were more often prescribed ACTH, whereas those with severe impairments were more likely to be prescribed a nonstandard treatment. This suggests that some of the poor response to nonstandard treatments may have been due to selection bias and underlying etiology. However, adjusted models demonstrate that response was not significantly affected by etiology or development once adjusted for treatment, although we had limited power to detect response differences between etiology and development groups. Based on these findings, there is not good evidence to alter treatment choice due to existence of a structural abnormality or pre-existing developmental delay. However, there is still likely a role for treatment-specific therapies, such as vigabatrin for those with tuberous sclerosis.

This study showed a trend for higher response rates with high-dose ACTH compared to low/intermediate-dose ACTH. However, this study was not sufficiently powered to determine differences in outcome between high-dose and low/intermediate-dose ACTH response. Due to the NISC dosing guidelines, there were fewer subjects on low/intermediate-dose ACTH. The most effective dose of ACTH is variably reported in the literature, and several reports suggest that low/intermediate-dose ACTH is as effective as high-dose ACTH. 5,13,27,29 The most recent evidence-based guidelines on the medical treatment of infantile spasms from the AAN/CNS suggest consideration for “low-dose” ACTH as an alternative to high-dose ACTH,5 although the majority of surveyed child neurologists use higher doses of ACTH.6 Although the efficacy of other therapies is often compared to the efficacy of ACTH, the dose, type, and duration of treatment of ACTH is inconsistent among studies, making interpretation of the available literature challenging. This merits further study.

There were some limitations to this study. First, the therapies were not randomized and providers were allowed to choose the medications, including those that were not considered “standard.” There is evidence of medication selection bias based on underlying etiology and developmental status, as well as variability in doses. However, in multivariate analysis we did not observe significant differences in overall treatment response patterns based on underlying etiology or development. Although this suggests that the lack of randomization did not contribute to the results of this study, we cannot exclude unknown confounders given the observational nature of study design. Developmental assessment was based on clinical examination and not on formal assessment tools, although recent studies suggest that tests such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development do not always correspond to long-term cognitive outcome and are associated with reporting errors.30,31 The use of broad developmental classifications in this study to determine the effect of development at the onset of spasms on treatment bias and response rates, although crude, was likely sufficient to identify those with moderate to severe developmental delay. As improvement in developmental outcomes is the ultimate goal in the treatment of infantile spasms, further long-term developmental assessments need to be performed. Finally, this study was not sufficiently powered to identify response to treatment based on each specific etiology and merging of etiological categories was necessary.

Using a multicenter prospective design, this study was able to incorporate larger numbers of children than previous studies, providing increasing insight about the most effective initial treatment for infantile spasms. Extended follow-up of a large cohort provides the most extensive data regarding relapse rates, and how relapse varies by treatment choice, providing a more complete clinical picture. The larger enrollment enabled assessment of response differences among developmental and etiologic subgroups. ACTH is likely more effective for children with infantile spasms regardless of development or etiology (perhaps with the exception of tuberous sclerosis). Our data do not support the use of nonstandard medications as initial therapy for infantile spasms. Additional prospective treatment trials are needed to determine optimal dosing of ACTH, further explore the implications of etiology, and provide expanded developmental assessments and long-term outcome of development and epilepsy.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was received from the American Epilepsy Society (to E.W. and K.G.K.) and Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation (to A.T.B. and D.N.).

We thank the numerous research assistants who gathered and entered data for making this study possible; Dr L. C. Kleinman for contributing SAS code; and Dr E. C. Norton for assisting with the regression risk analysis.

S.H. received grant support from Lundbeck, which owns rights to vigabatrin, and served on the scientific advisory board of Questcor/Mallinckrodt, which owns rights to ACTH.

Footnotes

Contributors from the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Consortium are listed as online supplementary material.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the conception and design of the study, and in the data analysis and editing.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1.Riikonen R, Donner M. Incidence and aetiology of infantile spasms from 1960 to 1976: a population study in Finland. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1979;21:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1979.tb01625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cowan LD, Hudson LS. The epidemiology and natural history of infantile spasms. J Child Neurol. 1991;6:355–364. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luthvigsson P, Olafsson E, Sigurthardottir S, Hauser WA. Epidemiologic features of infantile spasms in Iceland. Epilepsia. 1994;35:802–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidenvall R, Eeg-Olofsson O. Epidemiology of infantile spasms in Sweden. Epilepsia. 1995;36:572–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Go CY, Mackay MT, Weiss SK, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: Medical treatment of infantile spasms: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1974–1980. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318259e2cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mytinger JR, Joshi S. The current evaluation and treatment of infantile spasms among members of the child neurology society. J Child Neurology. 2012;27:1289–1294. doi: 10.1177/0883073812455692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheless JW, Clarke DF, Carpenter D. Treatment of pediatric epilepsy: expert opinion, 2005. J Child Neurol. 2005;20(suppl 1):S1–S56. doi: 10.1177/088307380502000101. quiz S9–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low NL. Infantile spasms with mental retardation. II. Treatment with cortisone and adrenocorticotropin. Pediatrics. 1958;22:1165–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sorel L, Dusaucy-Bauloye A. Findings in 21 cases of Gibbs’ hypsarrhythmia; spectacular effectiveness of ACTH [in French] Acta Neurol Psychiatr Belg. 1958;58:130–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.H. P. Acthar Gel [package insert] Union City, CA: Questcor Pharmaceuticals; 2010. [Accessed December 10, 2015]. Available at: http://www.acthar.com/pdf/Acthar-PI.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baram TZ, Mitchell WG, Tournay A, et al. High-dose corticotropin (ACTH) versus prednisone for infantile spasms: a prospective, randomized, blinded study. Pediatrics. 1996;97:375–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snead OC, III, Benton JW, Jr, Hosey LC, et al. Treatment of infantile spasms with high-dose ACTH: efficacy and plasma levels of ACTH and cortisol. Neurology. 1989;39:1027–1031. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.8.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hrachovy RA, Frost JD, Jr, Glaze DG. High-dose, long-duration versus low-dose, short-duration corticotropin therapy for infantile spasms. J Pediatr. 1994;124(5 pt 1):803–806. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hrachovy RA, Frost JD, Jr, Kellaway P, Zion TE. Double-blind study of ACTH vs prednisone therapy in infantile spasms. J Pediatr. 1983;103:641–645. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(83)80606-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wanigasinghe J, Arambepola C, Sri Ranganathan S, et al. The efficacy of moderate-to-high dose oral prednisolone versus low-to-moderate dose intramuscular corticotropin for improvement of hypsarrhythmia in West syndrome: a randomized, single-blind, parallel clinical trial. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lux AL, Edwards SW, Hancock E, et al. The United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study comparing vigabatrin with prednisolone or tetracosactide at 14 days: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17400-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kossoff EH, Hartman AL, Rubenstein JE, Vining EP. High-dose oral prednisolone for infantile spasms: an effective and less expensive alternative to ACTH. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:674–676. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hussain SA, Shinnar S, Kwong G, et al. Treatment of infantile spasms with very high dose prednisolone before high dose adrenocorticotropic hormone. Epilepsia. 2014;55:103–107. doi: 10.1111/epi.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elterman RD, Shields WD, Mansfield KA, et al. Randomized trial of vigabatrin in patients with infantile spasms. Neurology. 2001;57:1416–1421. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vigevano F, Cilio MR. Vigabatrin versus ACTH as first-line treatment for infantile spasms: a randomized, prospective study. Epilepsia. 1997;38:1270–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombroso CT. A prospective study of infantile spasms: clinical and therapeutic correlations. Epilepsia. 1983;24:135–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen-Sadan S, Kramer U, Ben-Zeev B, et al. Multicenter long-term follow-up of children with idiopathic West syndrome: ACTH versus vigabatrin. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lux AL, Osborne JP. A proposal for case definitions and outcome measures in studies of infantile spasms and West syndrome: consensus statement of the West Delphi group. Epilepsia. 2004;45:1416–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.02404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haycock GB, Schwartz GJ, Wisotsky DH. Geometric method for measuring body surface area: a height-weight formula validated in infants, children, and adults. J Pediatr. 1978;93:62–66. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia. 2010;51:676–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the risk?. A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44:288–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yanagaki S, Oguni H, Hayashi K, et al. A comparative study of high-dose and low-dose ACTH therapy for West syndrome. Brain Dev. 1999;21:461–467. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fedak EM, Patel AD, Heyer GL, et al. Optimizing care with a standardized management protocol for patients with infantile spasms. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:1340–1342. doi: 10.1177/0883073814562251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hrachovy RA, Frost JD, Jr, Kellaway P, Zion T. A controlled study of ACTH therapy in infantile spasms. Epilepsia. 1980;21:631–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1980.tb04316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costantini L, D’Ilario J, Moddemann D, et al. Accuracy of Bayley scores as outcome measures in trials of neonatal therapies. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:188–189. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hack M, Taylor HG, Drotar D, et al. Poor predictive validity of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development for cognitive function of extremely low birth weight children at school age. Pediatrics. 2005;116:333–341. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]