Abstract

Importance

It is not known if a reported decline in the risk of developing age-related macular degeneration (AMD) continued for people born during the baby boom years (1946–1964) or later. These data are important to plan for eye health care needs in the 21st century.

Objective

To determine if the 5-yr risk of AMD declined by generation and to identify factors that contributed to improvement in risk.

Design

Data came from two longitudinal cohort studies, the Beaver Dam Eye Study (1988–1990 and 1993–1995) and the Beaver Dam Offspring Study (2005–2008 and 2010–2013).

Setting

A population-based study of residents of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin ages 43–84 years in 1987–88 and their adult offspring ages 21–84 years in 2005–2008.

Participants

There were 4819 participants at risk for developing AMD based on fundus images obtained at baseline visits.

Main Outcome(s) and Measure(s)

Fundus images were graded for AMD using the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System. The incidence of AMD was defined as the presence at the 5-yr follow-up examination of pure geographic atrophy or exudative macular degeneration, or any type of drusen with pigmentary abnormalities, or soft indistinct drusen without pigmentary abnormalities.

Results

The mean baseline age of the cohort was 54 years and 44% were men. The 5-yr age-sex-adjusted incidence of AMD was 8.8% in the Greatest Generation (n=857 born 1901–1924), 3.0% in the Silent Generation (n= 2068 born 1925–1945), 1.0% in the Baby Boom Generation (n=1424 born 1946–1964), and 0.3% in Generation X (n=470 born 1965–1984). Adjusting for age and sex, each generation was more than 60% less likely to develop AMD than the previous generation (RR=0.34, 95%CI=0.24, 0.46). The generational effect (RR=0.40, 95%CI = 0.28, 0.57) remained significant adjusting for age, sex, smoking, education, exercise, non-HDL cholesterol, hsCRP, NSAID use, statins, and multivitamin use.

Conclusions and Relevance

The 5-yr risk of AMD declined by birth cohorts throughout the 20th century. Factors that explain this decline in risk are not known. However, this pattern is consistent with reported declines in risks of cardiovascular disease and dementia suggesting that aging baby boomers may experience better retinal health at older ages than previous generations.

INTRODUCTION

It is well-recognized that the U.S. population experienced dramatic increases in longevity during the twentieth century. The estimated life expectancy was 59 years for white people born in the US in 1921, 69 years by mid-century and 77 years by the end of the century.1 In the United States, because of this increased life expectancy and the Baby Boom (1946–1964), there is concern that large numbers of adults will experience age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the leading cause of blindness in older adults, increasing the need for vision care for older adults.2 However, in addition to living longer, older adults appear to enjoy better health than previous generations. Declines in the risk of cardiovascular disease3–4, dementias5–7 and other chronic conditions of aging8–9 have been reported for people born in the first half of the twentieth century. It was reported that the prevalence and 5-yr incidence of age-related macular degeneration declined by birth cohort between 1903 and 1942 in the Beaver Dam Eye Study.10 However, it is not known if the risk of AMD has declined for the Baby Boom generation, who are now turning 65 years old at the rate of 10,000 people per day.11

Rapid declines in incidence of non-communicable diseases are considered strong evidence that they are partially preventable as the impact of genetic change is slow and difficult to detect.8 During the 20th century there were tremendous changes in sanitation; housing; occupational safety; air and water quality and other environmental exposures; lifestyle and behavioral factors; food sources, availability, quality and safety; socioeconomic conditions; and advances in the treatment and prevention of medical conditions and infectious diseases which may have contributed to these improvements in risks of non-communicable diseases across generations.12,13 However with increasing obesity and sedentary lifestyles, exposures to new products and medications, and challenging economic conditions which may have unrecognized health risks, there is concern that the gains made in some health conditions in previous generations may be slowing, flattening, or disappearing and that people born during the Baby Boom and more recently may not continue to “age healthier” than their parents.14–16

The Beaver Dam Offspring Study (BOSS) which began in 2005 has been following the adult offspring (born 1926–1984) of the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study, an ancillary study following the Beaver Dam Eye Study (BDES) cohort (born 1902–1946).10,17,18 The purpose of this study was to determine the 5-yr incidence of AMD by generation to determine if the risk of AMD continued to decline for people born during the Baby Boom or later and to identify factors which contributed to improvement in risk.

METHODS

Analyses included data from two longitudinal cohort studies which measured the 5-yr incidence of AMD: the BDES and the BOSS.10,17 The BDES is a population-based cohort study of residents of the city or town of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, ages 43–84 years in 1987–88.10 Participants without AMD at the baseline examination in 1988–90 (at risk for developing AMD) and 5-yr follow-up data from 1993–1995 (n=2746) were included in these analyses. The BOSS examined the adult children (21 years of age or older) of the Beaver Dam cohort in 2005–2008.17,18 BOSS participants without AMD at baseline and with 5-yr follow-up data from 2010–2013 (n=2073) were included in these analyses. Retention of the at-risk group was high as 85% returned for the 5-yr follow-up visit and 91% of those returning had gradable images. Approval for this research was obtained from the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Wisconsin and informed written consent was obtained from all participants prior to each examination.

Similar standardized protocols were used in both studies at each examination.10,17 In the BDES 30° color fundus photographs centered on the disc (Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) standard field 1) and macula (ETDRS standard field 2) were taken of each eye through pharmacologically dilated pupils. In the BOSS, 45° 8.2-megapixel digital fundus images (ETDRS standard fields 1and 2) were obtained through pharmacologically dilated pupils (Canon Inc, Paramus, New Jersey). Images were graded by the University of Wisconsin Ocular Epidemiology Reading Center using the Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System.19 Previous studies have demonstrated that results from the two imaging methods are comparable.20

Among participants without AMD at the baseline visit, incident AMD was defined as the presence of pure geographic atrophy or exudative macular degeneration, or any type of drusen with pigmentary abnormalities, or soft indistinct drusen without pigmentary abnormalities.

Retinal vessel caliber measures were obtained using Ivan software (Fundus Photograph Reading Center, Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, University of Wisconsin) from fundus images centered on the optic disc. Individual arterioles and venules were measured from the retinal images following standardized methods. The average caliber of retinal arterioles and venules were summarized as the central retinal arteriolar equivalent (CRAE) and the central retinal venular equivalent (CRVE).21

Standardized questionnaires administered as interviews were used to obtain lifestyle, behavioral medical history, and medication data. Age was defined at the baseline examination. Generations were defined by year of birth: Greatest Generation (born 1901–1924, n=857), Silent Generation (born 1925–1945, n=2068), Baby Boom (born 1946–1964, n=1424), and Generation X (born 1965–1984, n=470). Smoking status was based on self-report of past, current, or never smoking. Heavy alcohol consumption was defined as ever consuming 4 or more alcoholic beverages daily. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher, diastolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher, or currently taking blood pressure medication. Height and weight were measured at the examination; obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2. Diabetes status was defined as a self-report of physician diagnosis or elevated hemoglobin A1C level greater than or equal to 6.5%. Exercise was defined as engaging at least once a week in physical activity long enough to work up a sweat. Participants self-reported use of multivitamins, statins and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Time spent outdoors in summer was used as an indicator of baseline sunlight exposure.

Serum total and high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol were measured on non-fasting samples. Non-HDL-cholesterol was calculated. Baseline serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) assays were performed at the same laboratory at the University of Minnesota.22 Baseline BDES hsCRP was measured using a latex-particle enhanced immunoturbidmetric method (Kamiya Biomedical Company, Seattle, WA) read on a Roche/Hitachi 911 Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Baseline BOSS hsCRP levels were measured using a latex particle enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, IN) read on the Roche Modular P Chemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). For both methods, the reference range was 0–5 mg/L, sensitivity was 0.1mg/L, and the inter-assay coefficient of variation was 4.5%. Baseline hsCRP was divided into 3 risk groups, <1.0, 1.0–3.0, >3.0 mg/L.22 Baseline serum IL-6 was measured using the quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique (QuantiKine High Sensitivity kit; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). The IL-6 reference range was 0.45–9.96 pg/mL and the laboratory inter-assay CV was 11.7%. IL-6 was analyzed as tertiles.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Exact binomial confidence intervals were calculated for incidence estimates by age group and overall. Age- and sex-adjusted relative risk estimates associated with baseline risk factors were calculated using a modified Poisson regression approach with a robust error variance.23 This approach was used to estimate the relative risk associated with each successive generation, both in an age- and sex-adjusted model and a multivariable-adjusted model. In these models, generation was treated as an ordered factor, resulting in estimated relative risks associated with one generation compared to the previous generation. Estimated five-year incidence estimates, by generation, and by generation and age, were plotted from models using the same approach. Similar models were built using indicator variables for generation.

RESULTS

There were 4819 participants (44% were men) and the mean age at baseline was 54 years (SD=10.8). 1The overall 5-yr incidence of AMD was 4.2% (Table 1) and increased by age group from 0.3% among participants less than 40 years of age to 19.6% among participants 80–86 years of age at baseline. Baseline characteristics of those who developed incident AMD and those who remained free of AMD are shown in Table 2. Adjusting for age and sex, there were no associations between smoking, diabetes, hypertension, obesity, exercise, history of heavy drinking, hsCRP, IL-6, NSAID use, CRVE, CRAE, or sunlight exposure and the incidence of AMD. Non-HDL cholesterol, multivitamin use statin use, and education were associated with the age-sex-adjusted risk of AMD; multivitamin use and education remained significant independent predictors in a multivariable model (data not shown).

Table 1.

5-Year Incidence of AMD by Age Group

| Age Group, years | N at Risk | n cases | % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 22–39 | 363 | 1 | 0.3 (0.0, 1.5) |

| 40–49 | 1445 | 15 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) |

| 50–59 | 1596 | 45 | 2.8 (2.1, 3.8) |

| 60–69 | 967 | 72 | 7.5 (5.9, 9.3) |

| 70–79 | 397 | 61 | 15.4 (12.0, 19.3) |

| 80–86 | 51 | 10 | 19.6 (9.8, 33.1) |

| All | 4819 | 204 | 4.2 (3.7, 4.8) |

Table 2.

Baseline Risk Factors (n, %) by 5-Year Incidence of AMD and Associated Age-sex-Adjusted Relative Risks of AMD (RR, 95% CI)

| Characteristic | Incident AMD (n=204) |

No AMD (n=4615) |

Age-sex-adjusted RR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n(%) | n(%) | ||

|

| |||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 110 (53.9) | 2592 (56.2) | REF |

| Male | 94 (46.1) | 2023 (43.8) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.55) |

|

| |||

| Smoking | |||

| Never | 97 (47.6) | 2267 (49.1) | REF |

| Past | 79 (38.7) | 1481 (32.1) | 1.07 (0.79, 1.44) |

| Current | 28 (13.7) | 866 (18.8) | 1.04 (0.69, 1.57) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes | 20 (9.8) | 270 (5.9) | 1.18 (0.75, 1.83) |

|

| |||

| Education (years) | |||

| 0–12 | 154 (75.5) | 2329 (50.6) | 1.32 (0.91, 1.93) |

| 13–15 | 18 (8.8) | 1136 (24.7) | 0.53 (0.30, 0.93) |

| 16+ | 32 (15.7) | 1136 (24.7) | REF |

|

| |||

| Hypertension | 113 (55.4) | 1814 (39.3) | 1.08 (0.83, 1.43) |

|

| |||

| Obesity | 75 (36.8) | 1822 (39.7) | 0.95 (0.72, 1.24) |

|

| |||

| Exercise | 70 (34.3) | 2243 (48.6) | 0.80 (0.60, 1.07) |

|

| |||

| History of Heavy Drinking | 30 (14.7) | 757 (16.4) | 1.10 (0.75, 1.61) |

|

| |||

| hsCRP mg/L | |||

| <1 | 46 (22.8) | 1521 (33.7) | REF |

| 1–3 | 82 (40.6) | 1720 (38.1) | 1.17 (0.82, 1.66) |

| >3 | 74 (36.6) | 1273 (28.2) | 1.31 (0.91, 1.88) |

|

| |||

| NSAID Use | 80 (39.2) | 2041 (44.2) | 0.85 (0.65, 1.12) |

|

| |||

| Statin Use | 2 (1.0) | 300 (6.5) | 0.18 (0.04, 0.71) |

|

| |||

| Multivitamin Use | 65 (32.0) | 1843 (40.1) | 0.69 (0.52, 0.91) |

|

| |||

| IL6 pg/mL (mean, SD) | 3.3 (3.9) | 2.7 (5.3) | 1.12 (0.88, 1.42)a |

|

| |||

| CRVE (mean, SD) | 228.9 (20.6) | 227.5 (21.3) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.10)b |

|

| |||

| CRAE (mean, SD) | 149.1 (13.9) | 150.3 (14.5) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10)b |

|

| |||

| Non-HDL-cholesterol mg/dL (mean, SD) | 183 (43) | 168 (44) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06)c |

|

| |||

| Sunlight | |||

| Low | 92 (45.5) | 1753 (38.0) | REF |

| Moderate | 66 (32.7) | 1784 (38.7) | 0.90 (0.66, 1.23) |

| High | 44 (21.8) | 1074 (23.3) | 1.00 (0.69, 1.46) |

For each one ln(pg/mL) increase.

For each ten µ increase

For each 10 mg/dL increase

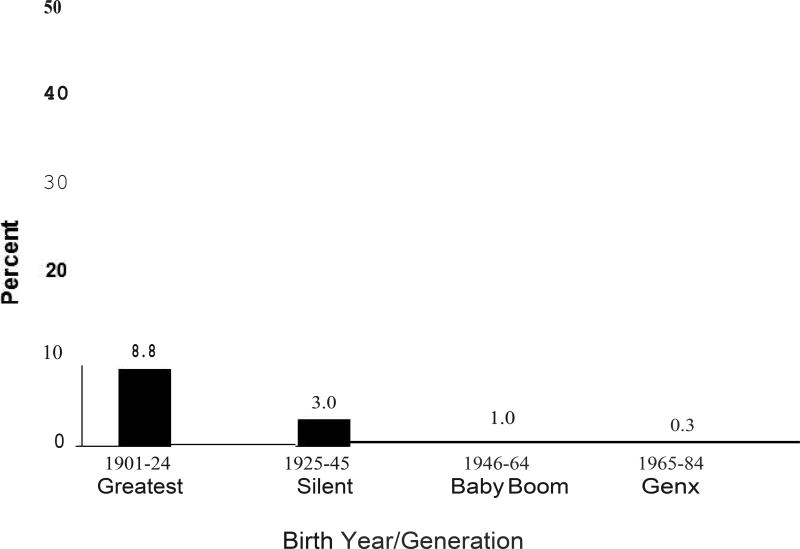

As shown in Figure 1, the age-sex-adjusted incidence of AMD also varied by generation or birth cohort. The age-sex-adjusted incidence of AMD was 8.8% among those in the Greatest Generation (1901–1924), 3.0% among the Silent Generation (1925–1945), 1.0% among the Baby Boom Generation (1946–1964), and 0.3% among Generation X (1965–1984). Adjusting for age and sex, each generation was more than 65% less likely to develop AMD than the previous generation (RR=0.34, 95%CI=0.24, 0.46) (Table 3). Age-generation-specific 5-yr incidence are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Figure 1.

Age-sex-adjusted 5-year Incidence of AMD by Generation

Table 3.

Generation and the 5-yr Incidence of AMD

| Model | N | Generation Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Risk |

95% CI | ||

| Age-sex-adjusted Model (full cohort) | 4819 | 0.34 | 0.24, 0.46 |

| Age-sex-adjusted Model (complete data) | 4669 | 0.33 | 0.24, 0.46 |

| Multivariablea-adjusted Model* | 4669 | 0.40 | 0.28, 0.58 |

Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, education, exercise, hsCRP, non-HDL- cholesterol, NSAID use, statin use, and multivitamin use.

To determine if potential AMD risk factors mediate this generational trend, a multivariable model was constructed adjusting for age, sex, smoking, education, exercise, non-HDL cholesterol, hsCRP, NSAID use, statin use, and multivitamin use. The generational effect remained statistically significant but was slightly attenuated (RR=0.40, 95%CI=0.28, 0.58) (Table 3). In addition to generation, only age remained as a significant independent predictor of risk of AMD. Adjusting for family clusters did not alter these results. A multivariable model using indicator variables for generation showed statistically significant associations for each generation (data not shown). There were no cases of late AMD in the Baby Boom or Generation X cohorts so analyses of late stage disease were not possible

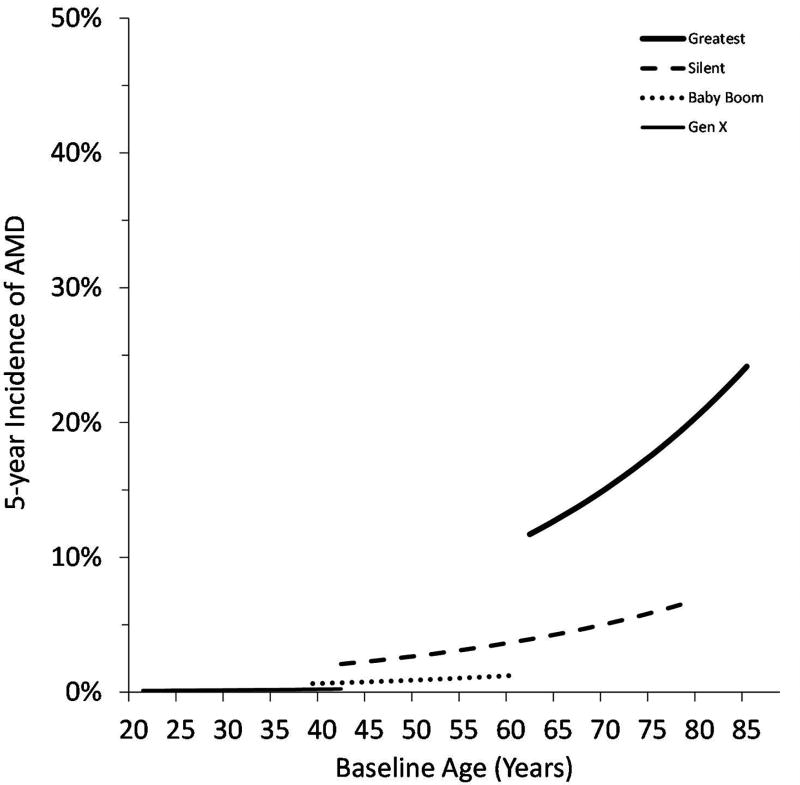

Figure 2 illustrates the estimated incidence of AMD by generation and age from the multivariable model. Comparing across generations at a specific age, the incidence of AMD was lower in the Baby Boom Generation than the Silent Generation, which in turn had a lower incidence than the Greatest Generation. Generation X is very young, but even at this early phase, the estimated incidence appeared to follow this trend, and was lower than the incidence among young Baby Boomers.

Figure 2.

Estimated 5-year Incidence of AMD by Generation and Age

DISCUSSION

The five-year incidence of AMD was 60% lower for each successive generation. Therefore, people born during the Baby Boom years (1946–1964) were 60% less likely to develop AMD than the Silent Generation (1925–1945) who were 60% less likely to develop AMD than the Greatest Generation (1901–1924). This dramatic decline in the incidence across three generations suggests that environmental/behavioral factors are important risk factors in the etiology of AMD as rapid genetic changes are unlikely.8 Our results are consistent with the previously reported decline in risk for participants born before 1943.10 This study extends the findings to people born during the Baby Boom and represents the largest cohort of aging adults. Although adults in Generation X are just beginning to enter the risk years for AMD they, too, appear to be experiencing a decline in risk of AMD but additional follow-up is needed to determine if this pattern continues when they become senior citizens. This pattern is consistent with a recent report of declining prevalence of AMD in European countries.24

In this study, smoking a well-recognized risk factor for AMD25, was not associated with the 5-yr risk which is consistent with results from the 5-yr follow-up of the BDES and Blue Mountains Eye Study.26,27 Declines in smoking exposure in recent decades and the short follow-up time may have limited our ability to detect an association. The effect of generation was slightly attenuated but remained statistically significant in the model controlling for potential AMD risk factors, such as smoking, markers of inflammation, non-HDL cholesterol, education, medication use, and multivitamin use,. These results suggest that other modifiable factors, yet to be identified, may be important contributors to the risk of AMD.

The decline in AMD is consistent with reports of declines in the incidence of CVD and dementia observed in the same time period, and with improvements in longevity.1,3–7 These diseases involve vascular and inflammatory pathways, consistent with the pathways hypothesized to be important in the development of AMD. We did not have a baseline measure of atherosclerosis in the BDES cohort so we were unable to directly control for atherosclerosis. Controlling for inflammation did not explain the generation effect perhaps because short-term exposure to higher levels of inflammation as captured by the single measure of hsCRP or IL-6 may be insufficient to cause damage leading to AMD.

The reasons for the dramatic decline in CVD, recognized as early as since the 1970s and the more recently recognized decline in dementia remain unknown, suggesting that we may never know the reasons for this decline in AMD risk.28 These generalized improvements in health may have their roots in broad changes in the environment such as cleaner air and water and improvements in sanitation which have reduced exposures to neurotoxins, particulates, and infectious agents, which may contribute to chronic diseases of aging.12 Alternatively, with the advent of antibiotics and vaccines, each generation experienced fewer serious infectious diseases of childhood and they may have been more likely to be milder or shorter duration.13 Infectious diseases may have long-term sequelae by increasing risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease although exact mechanisms are uncertain.29 Social stress, another risk factor for chronic diseases of aging30, has also differed across generations as historic events have exposed each generation to dramatically different living conditions, worries, and challenges. The Greatest Generation lived through numerous wars, the Great Depression, and food rationing which may have had adverse long-term effects on health, including ocular health. Many age-related conditions may have their origins in childhood or in utero exposures31, so improvements in maternal health, along with improvements in childhood nutrition and health care may have contributed to the observed decline.

The importance of the finding remains that aging Baby Boomers may be less likely to develop AMD than previous generations if this trend continues as they age into the primary risk years. Thus, projections about future eye health care needs related to AMD may have over-estimated the public health burden.2 The number of older adults in the U.S. is expected to increase as the baby boom cohort ages32, but AMD may be associated with increased mortality33 and there are indications that previous gains in life expectancy may not continue34, making it difficult to accurately predict the future number of people who will need medical care for AMD by mid-century. The implications for research include the need for novel hypotheses to identify new ways to reduce the risk of AMD for tomorrow’s elders and to determine if the primary risk factors for AMD vary by generation because of changes in the prevalence of exposures (i.e., if the prevalence of a known risk factor declines substantially another factor may emerge as important). Because the incidence of AMD is so low among the Baby Boom generation, large studies will be needed to have adequate power to investigate etiologic risk factors. Combined with improvements in treatments, this rapid and dramatic decline in 5-yr incidence suggests that the Baby Boom generation may avoid the loss of vision due to AMD that has been a major source of disability for prior generations.

This study is limited by the inability to disentangle birth cohort from period effects. Our approach recognizes this impossibility and assesses the joint effect of risk for people born in different time periods living through different periods at different ages. For planning for future clinical needs, it is important to know the risk for people entering the major risk period, rather than relying on data generated from current or past elders.

Although these cohorts were predominately non-Hispanic whites (NHW), and therefore, these results may not be generalizable to other racial/ethnic groups, NHW are known to have higher risk of AMD than African Americans, Hispanics, and Chinese Americans.35 It is important to determine if other racial/ethnic groups have experienced the same decline across generations or if the risk has increased. The risk among NHW may differ by geographic region36 so studies of NHW living in other regions in the US are needed as the BDES cohort all lived in one mid-western city in 1987–88. The offspring were not geographically constrained (they could have become adults before their parents moved to Beaver Dam) although the majority lived in Wisconsin at the time of the baseline examination in 2005–2008. Geographic differences also may reflect variation in environmental exposures.

It is possible that some of the decline among the BOSS participants may reflect changes in the imaging methods between the two studies. The BDES used film-based systems while the BOSS examinations used digital imaging. However previous work has demonstrated comparable results are obtained by these two systems20, the grading for both studies was done by the same center, and the decline began in the generations included in the BDES, lessening the likelihood this pattern is due to measurement differences.

The strengths of the study remain the population-based design, the high retention rates in both cohorts, the objective assessments of AMD, and measurement of numerous potential confounders. The offspring design of the BOSS reduces the genetic heterogeneity that would be present in unrelated cohorts and increases the probability that any change is attributable to differences in modifiable exposures.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the 5-yr risk of developing AMD was dramatically lower for generations born later in the 20th century than those born earlier. We have extended these findings to the large group of Baby Boomers currently entering the older ages at which AMD presents. Although we were unable to identify the factors that explained the change, this study suggests that modifiable factors contribute to the etiology of AMD. These results suggest that the current epidemic of AMD among today’s elders may wane over time and that future research may uncover opportunities for primary prevention of this vision-threatening disorder. Prospective epidemiological studies are needed to confirm these findings in other populations.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question

Has the risk of AMD declined for people born in the latter half of the 20th century?

Findings

In this longitudinal cohort study of the incidence of AMD, the risk of AMD declined by 60% for each successive generation. Baby boomers were significantly less likely to develop AMD than members of the Silent or Greatest generations.

Meaning

This dramatic decline in the incidence of AMD suggests that aging baby boomers will experience better retinal health longer than previous generations.

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by R01AG021917 (KJC) from the National Institute on Aging and the National Eye Institute, U10EY06594 (RK, BEKK) from the National Eye Institute, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging, National Eye Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The funding agencies had no roles in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors reported any potential conflicts of interest involving the work under consideration for publication, or relevant financial activities outside the submitted work or any other relationships or activities that readers could perceive to have influenced, or that give the appearance of potentially influencing what is written in the submitted work.

Contributions and Access to Data

Dr. Karen J. Cruickshanks had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Dr. Cruickshanks was responsible for the concept, design and conduct of the Beaver Dam Offspring Study, obtained funding, directed the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data. Dr. Cruickshanks and Ms. Johnson prepared the draft manuscript and incorporated comments and suggestions from the co-authors. All authors provided advice on the analyses and interpretation of results, contributed to the writing of the article and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission the JAMA - Ophthalmology. The Drs. Klein obtained funding for and directed the conduct of the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ms. Dalton, Dr. Fischer, Dr. Huang and Ms. Schubert were involved in the conduct of the study, acquisition of subjects and data. Mr. Nondahl performed the statistical analyses.

References

- 1.Arias E. United States Life Tables, 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(11):1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman DS, O'Colmain BJ, Muñoz B, Tomany, et al. Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):564–72. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.564. Erratum in: Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(9):1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGovern PG, Pankow JS, Shahar E, et al. Recent trends in acute coronary heart disease--mortality, morbidity, medical care, and risk factors. The Minnesota Heart Survey Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;4;334(14):884–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604043341403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Roger VL, Dunlay SM, Go AS, Rosamond WD. Challenges of ascertaining national trends in the incidence of coronary heart disease in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(6):e001097. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, et al. Incidence of dementia over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(1):93–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1604823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews FR, Stephan BCM, Robinson L, et al. A two decade dementia incidence comparison from the cognitive function and ageing studies I and II. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11398. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerstorf D, Ram N, Hoppmann C, Willis SL, Schaie W. Cohort differences in cognitive aging and terminal decline in the Seattle Longitudinal Study. Dev Psychol. 2011;47(4):1026–41. doi: 10.1037/a0023426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doll R, Peto R. The Causes of Cancer. New York: Oxford University Press; 1981. pp. 1197–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doll R. Progress against cancer: an epidemiologic assessment. The 1991 John C. Cassel Memorial Lecture. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(7):675–88. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein R, Knudtson MD, Lee KE, Gangnon RE, Klein BE. Age-period-cohort effect on the incidence of age-related macular degeneration: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(9):1460–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohn D, Taylor P. Baby Boomers Approach 65 – Glumly. [Accessed June 9, 2017];Pew Research Center. 2010 Dec 20; http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/12/20/baby-boomers-approach-65-glumly/

- 12.Garte S. Where We Stand: A Surprising Look at the Real State of Our Planet. New York, NY: AMACOM; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atkinson W, Furphy L, Gantt J, Mayfield M, Rhyne G, editors. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 3. Centers for Disease Control; Atlanta, GA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goff DC, Gillespie C, Howard G, Labarthe DR. Is the obesity epidemic reversing favorable trends in blood pressure? Evidence from cohorts born between 1890 and 1990 in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(8):554–61. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badley EM, Canizares M, Perruccio AV, Hogg-Johnson S, Gignac MA. Benefits gained, benefits lost: comparing baby boomers to other generations in a longitudinal cohort study of self-rated health. Milbank Q. 2015;93(1):40–72. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King DE, Matheson E, Chirina S, Shankar A, Broman-Fulks J. The status of baby boomers’ health in the United States: the healthiest generation? JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:385–386. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein R, Cruickshanks KJ, Nash SD, et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and associated risk factors. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(6):750–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhan W, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, et al. Generational differences in the prevalence of hearing impairment in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(2):260–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein R, Davis MD, Magli YL, Segal P, Hubbard L, Klein BEK. The Wisconsin Age-Related Maculopathy Grading System. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1128–1134. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klein R, Meuer SM, Moss SE, Klein BE, Neider MW, Reinke J. Detection of age-related macular degeneration using a nonmydriatic digital camera and a standard film fundus camera. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(11):1642–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.11.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knudtson MD, Lee KE, Hubbard LD, Wong TY, Klein R, Klein BE. Revised formulas for summarizing retinal vessel diameters. Curr Eye Res. 2003;27:143–149. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.27.3.143.16049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nash SD, Cruickshanks KJ, Schubert CR, et al. Long-term variability of inflammatory markers in a population-based cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1269–76. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colijn JM, Buitendijk GHS, Prokofyeva E, et al. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Europe: The Past and the Future. Ophthalmology. 2017 Jul 14; doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.035. pii: S0161-6420(16)32475-7. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thornton J, Edwards R, Mitchell P, Harrison RA, Buchan I, Kelly SP. Smoking and age-related macular degeneration: a review of association. Eye (Lond) 2005 Sep;19(9):935–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein R, Klein BEK, Moss SE. Relation of smoking to the incidence of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Amer J Epidemiol. 1998;147:103–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Smith W, Leeder SR. Smoking and the five-year incidence of age-related maculopathy: The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002 Oct;120(10):1357–63. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones DS, Greene JA. The decline and rise of coronary heart disease. Understanding public health catastrophism. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):1207–18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieto FJ. Infections and atherosclerosis: new clues from an old hypothesis? Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(10):937–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance: the Fourth Wade Hampton Frost Lecture. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(2):107–23. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barker DJ. Childhood causes of adult diseases. Arch Dis Child. 1988;63(7):867–869. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.7.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. Current Population Reports P25-1138. US Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2010. The next four decades. The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGuinness MB, Karahalios A, Finger RP, Guymer RH, Simpson JA. Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017 Jun;24(3):141–152. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1259422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu J, Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Arias E. NCHS Data Brief, No. 267. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. Mortality in the United States, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fisher DE, Klein BE, Wong TY, et al. Incidence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in a Multi-Ethnic United States Population: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(6):1297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruickshanks KJ, Hamman RF, Klein R, Nondahl DM, Shetterly SM. The prevalence of age-related maculopathy by geographic region and ethnicity. The Colorado-Wisconsin study of age-related maculopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:242–250. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150244015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.