Abstract

We retrospectively reviewed outcomes of treatments with cisplatin and topotecan in patients with previously-treated uterine cervix cancer.

We analyzed the medical records of patients with advanced (stage IVB) or recurrent or persistent squamous or non-squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, who were treated with cisplatin and topotecan as a second-line chemotherapy between January 2000 and December 2015. The patients were treated with a combination of cisplatin (50 mg/m2 for 1 day) and topotecan (0.75 mg/m2 for 3 days) once every 3 weeks. Treatment response, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were analyzed in all patients and between responder and non-responder groups (responders showed at least a partial response to prior systemic chemotherapy).

Thirty-nine patients with a median age of 47 years (range, 32–73 years) were treated with cisplatin and topotecan. The median PFS was 4.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–7.9 months) and the median OS was 14.1 months (95% CI, 10.0–18.2 months). The overall response rate (ORR) was 30.8%, and the disease control rate was 56.4%. The ORR was significantly better in the responder group compared with the non-responder group (50.0% vs 10.5%; P = .008). All patients reported some grade of hematological toxicity. The most frequently encountered toxicity was anemia, with a rate of 59.7% for any grade and 13.2% for grade 3 or 4.

The combination of cisplatin and topotecan was effective as second-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced/recurrent uterine cervix cancer.

Keywords: chemotherapy, cisplatin, topotecan, uterine cervical carcinoma

1. Introduction

Cancer of the cervix is one of the most common worldwide malignancies. Fortunately, the frequency of occurrence of cervical cancer has decreased because of cytological screening (e.g., the Pap smear test), DNA testing for high risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, and HPV vaccination. HPV types 16 and 18 cause cervical and anal cancer, and reduction in these HPV types could prevent >70% of cervical cancers worldwide.[1] However, cervical cancer remains a significant problem, with 12,990 new cases and 4120 deaths annually in the United States[2] and 3500 new cases and 960 deaths annually in the Republic of Korea.[3]

Cisplatin is the most active, cytotoxic, systemic, single chemotherapeutic agent for advanced carcinomas of the cervix. Its efficacy was first reported as an objective response rate (ORR) of 44% in previously untreated patients.[4] Since its initial use, cisplatin-based combination therapy has been reported to result in a higher response than that of cisplatin single-agent therapy. The combination of cisplatin and ifosfamide showed an improvement compared with cisplatin alone, with an ORR of 13.3% and progression-free survival (PFS) of 1.4 months, although there was no improvement in overall survival (OS). In the report, the significantly increased leukopenia toxicity, renal toxicity, peripheral neurotoxicity, and central nervous system toxicity in the combination regimen were a concern.[5] In another regimen, cisplatin plus paclitaxel showed an improvement compared with cisplatin alone, with an ORR of 17%, PFS of 2 months, and a sustained quality of life, although no significant difference in the median OS was observed.[6] Because cisplatin-based combination therapy showed better results, another study evaluated 4 cisplatin-based regimens, including combinations with paclitaxel, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, and topotecan. The combination of cisplatin and paclitaxel showed a better median OS compared with the other combination regimens (12.9 months vs 10–10.5 months).[7,8] Recently, a phase III randomized trial of bevacizumab plus combination chemotherapy was performed for patients with recurrent, persistent, or metastatic cervical cancer. Bevacizumab, compared with chemotherapy alone, showed a significantly increased OS (17.0 months vs 13.3 months).[9] After that study, a combination of platinum and paclitaxel with/without bevacizumab was accepted as the standard treatment for patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer.

Unfortunately, most responses to chemotherapy are partial and short in duration, and more effective treatments for patients with progressive disease after standard first-line chemotherapy have yet to be identified. Finding enough patient subjects to obtain sufficient power to test novel strategies is also a challenge.

Topotecan is one of the most effective drugs for the treatment of cervical cancer. Furthermore, the combination of cisplatin 50 mg/m2 day 1 and topotecan 0.75 mg/m2 days 1 to 3 every 3 weeks, when compared with cisplatin alone, has been shown to improve OS from 6.5 to 9.4 months in patients who were unsuitable candidates for curative treatment with advanced/recurrent and metastatic cervical cancer.[10] The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) has reported on the phase III trial of 4 cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage IV, recurrent, or persistent cervical cancer; paclitaxel and cisplatin, vinorelbine and cisplatin, gemcitabine and cisplatin, and topotecan and cisplatin. The topotecan and cisplatin combination was not superior to paclitaxel and cisplatin in terms of OS, whereas trends in RR, PFS, and OS favored paclitaxel and cisplatin.[7] However, the efficacy of topotecan and cisplatin doublet was not reported in patients with progressive disease after front-line palliative chemotherapy although it could be used as one of several systemic therapy regimens in second-line setting.

Based on these results, we assessed the clinical benefit of cisplatin and topotecan in patients with incurable cervical cancer who showed failure after first-line chemotherapy and for whom no further treatment has been established yet. We describe the results of retrospective analyses of cisplatin plus topotecan, including the treatment outcomes of these patients

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

We collected and reviewed the medical records of patients diagnosed with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer who were treated with cisplatin plus topotecan as a second-line therapy from January 2000 to December 2015 at Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Republic of Korea.

We included patients ≥18 years of age with histologically proven advanced (stage IVB) or recurrent or persistent squamous or non-squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix who were treated with cisplatin plus topotecan. Other inclusion criteria included having >1 measurable lesion according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1),[11] an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score ≤2, treatment with 1 prior systemic chemotherapy regimen, an absolute neutrophil count ≥1500/μL and platelet count (as hematological parameters) ≥100,000/μL, serum creatinine level (as a renal parameter) ≤1.5-fold the institutional upper limit of normal (ULN), serum bilirubin level (as a hepatic parameter) ≤1.5-fold the ULN, and both aspartate aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels ≤2.5-fold the ULN.

We excluded patients who had other malignancies within the last 5 years, patients with prior non-cytotoxic therapies, and patients requiring hospital admission for active bleeding, central nervous system diseases, or severe infections. Patients were also excluded for significant cardiovascular diseases (e.g., uncontrolled hypertension, unstable angina, uncontrolled congestive heart failure, or uncontrolled arrhythmias within 6 months of registration), pregnancy or nursing, or major surgical procedures within the last 30 days. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital.

2.2. Treatment

The patients were treated with cisplatin (50 mg/m2 for 1 day) and topotecan (0.75 mg/m2 for 3 days). The drugs were infused separately, and the cycles were repeated every 21 days. The cycles were delayed if the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was <1500/μL, and/or the platelet count was <100,000/μL on the proposed day of treatment. All patients received prophylactic medication for chemotherapy-induced nausea/vomiting. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) was administered to patients with febrile neutropenia or with an ANC <500/μL. Chemotherapy was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient refusal, with a maximum of 6 cycles.

2.3. Response assessment

Response evaluations were performed according to clinical assessments and imaging studies after every 2 or 3 cycles in the absence of overt progression. The treatment response was classified as complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD) according to the RECIST criteria, version 1.1, and toxicity was evaluated based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0 (http://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc).

2.4. Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive statistics included medians with/without ranges. Differences between 2 groups were tested using the t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. PFS was defined as the time between the first administration of chemotherapy and the date of tumor progression. OS was defined as the time between the first administration of chemotherapy and the date of last contact or death. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with the log-rank test. A P-value <.05 was considered significant. SPSS statistical software for Windows, version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Patient population

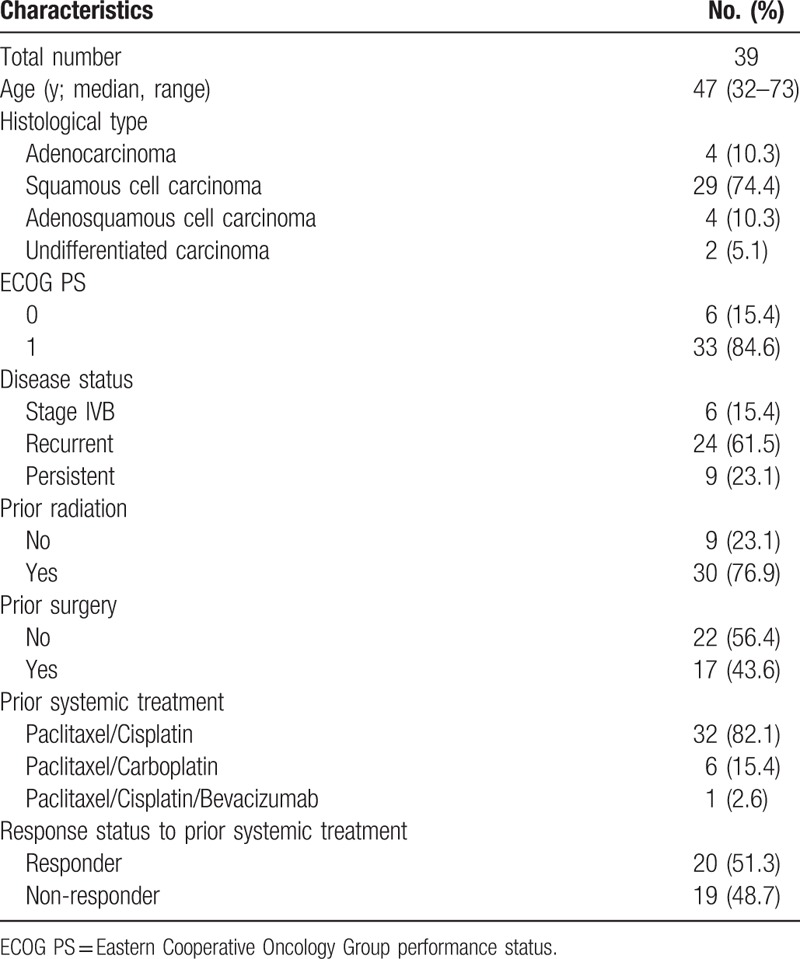

Thirty-nine patients with advanced, recurrent, or persistent cervical cancer were treated with a combination of cisplatin and topotecan as second-line chemotherapy between January 2000 and December 2015. The median patient age was 47 years (range, 32–73 years). The distribution of the histological subtypes was as follows: adenocarcinoma (n = 4), squamous cell carcinoma (n = 29), adenosquamous cell carcinoma (n = 4), and undifferentiated carcinoma (n = 2). All patients had previously received platinum-based cytotoxic chemotherapy before the study treatment: 32 (82.1%) a combination of paclitaxel and cisplatin, 6 (15.4%) a combination of paclitaxel and carboplatin, and 1 (2.6%) a bevacizumab-containing regimen as first-line chemotherapy. Twenty (51.3%) patients showed at least a PR to prior systemic chemotherapy (responders), and 19 (48.3%) patients did not show any tumor response to prior chemotherapy (non-responders) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics.

3.2. Tumor responses

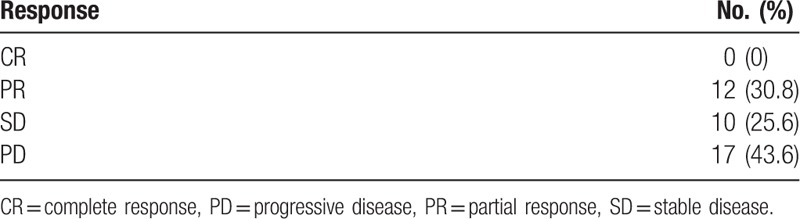

A CR was not observed, and a PR was observed in 12 (30.8%) patients. The ORR was 30.8%, and the disease control rate (DCR) was 56.4% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Best response to combination of cisplatin and topotecan.

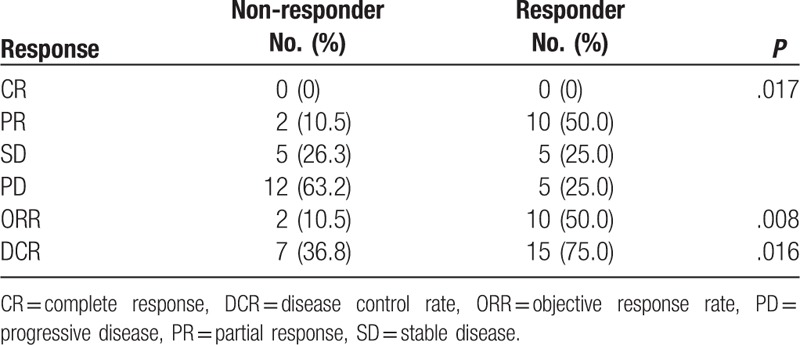

The ORR was significantly better in the responder group compared with the non-responder group (50.0% vs 10.5%; P = .008), and the DCR was also better in the responder group (75.0% vs 36.8%; P = .016) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Best response to combination of cisplatin and topotecan according to response status to prior systemic treatment.

3.3. Survival outcomes

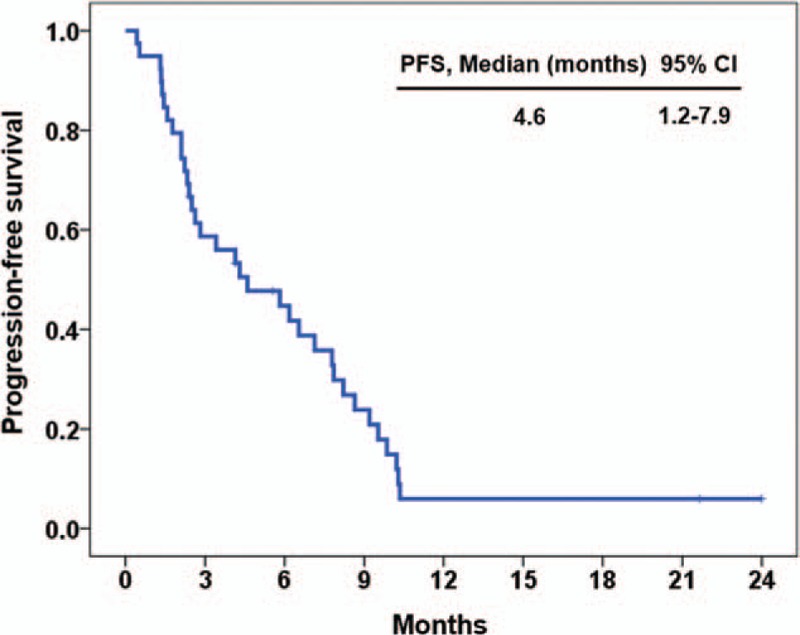

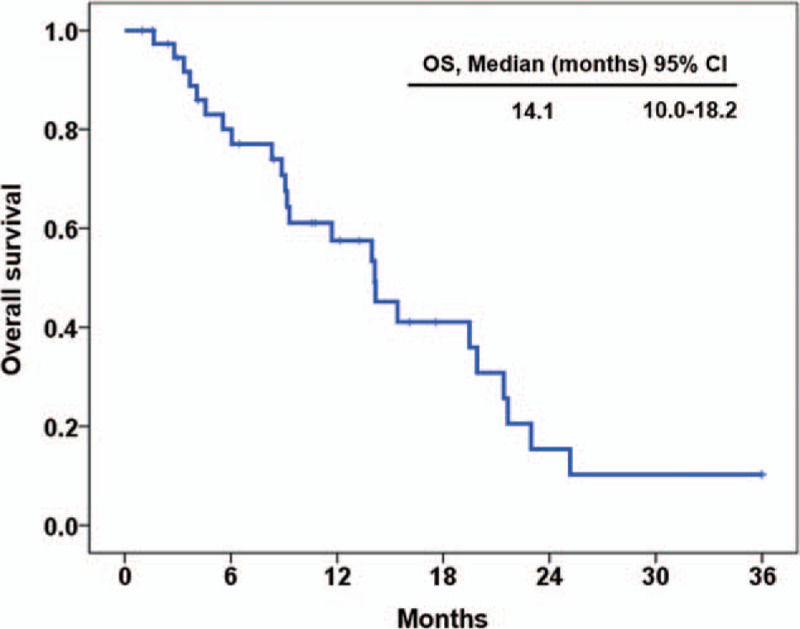

In all patients, the median PFS was 4.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–7.9) (Fig. 1) and the median OS was 14.1 months (95% CI, 10.0–18.2) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Progression free survival for all patients (n = 39).

Figure 2.

Overall survival for all patients (n = 39).

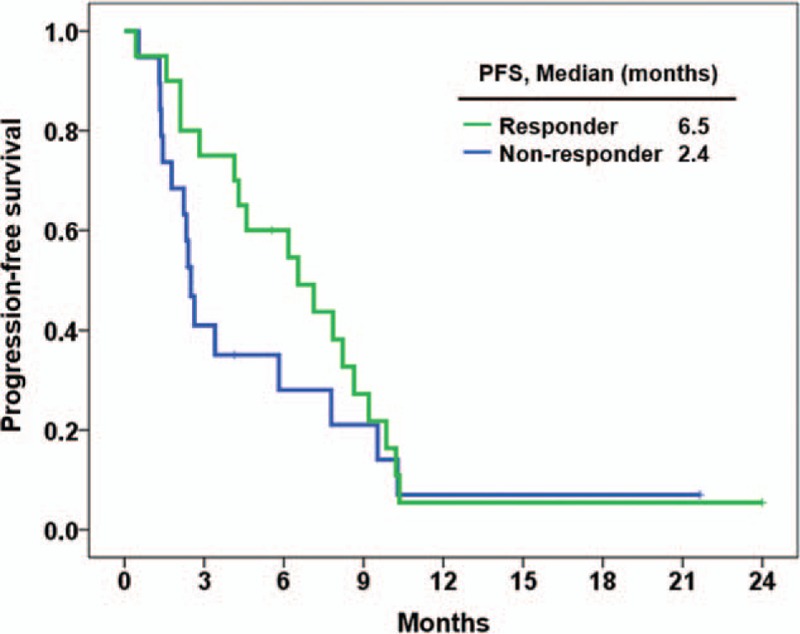

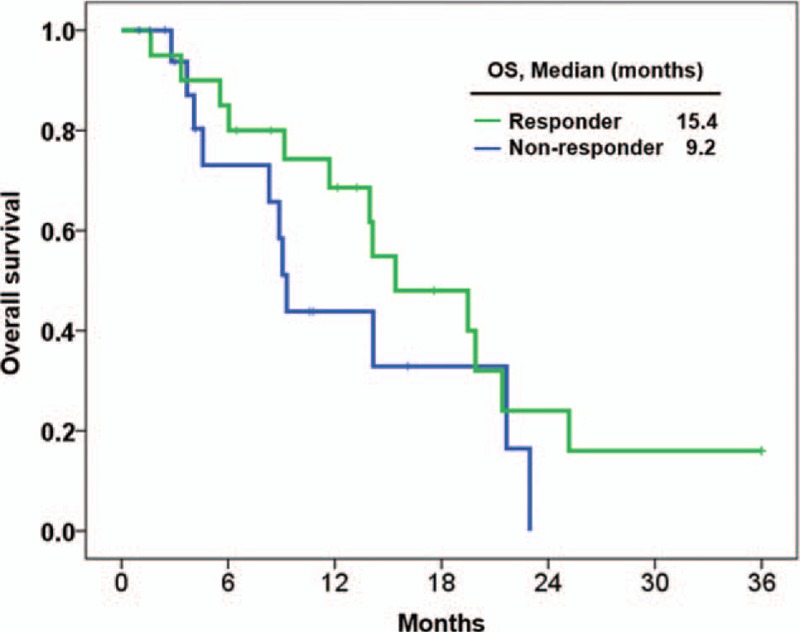

The median PFS was longer in the responder group compared with the non-responder group (6.5 months vs 2.4 months; P = .244; hazard ratio [HR], 0.66; 95% CI, 0.33–1.32) (Fig. 3), and the median OS was also longer in the responder group (15.4 months vs 9.2 months; P = .201; HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.25–1.34) (Fig. 4). The estimated PFS and OS rates at 6 months were 44.7% and 80.0% for all patients, 60.0% and 80.0% for responders, and 28.1% and 73.1% for non-responders, respectively.

Figure 3.

Progression free survival between responder (n = 20) and non-responder (n = 19) groups.

Figure 4.

Overall survival between responder (n = 20) and non-responder (n = 19) groups.

3.4. Safety profiles

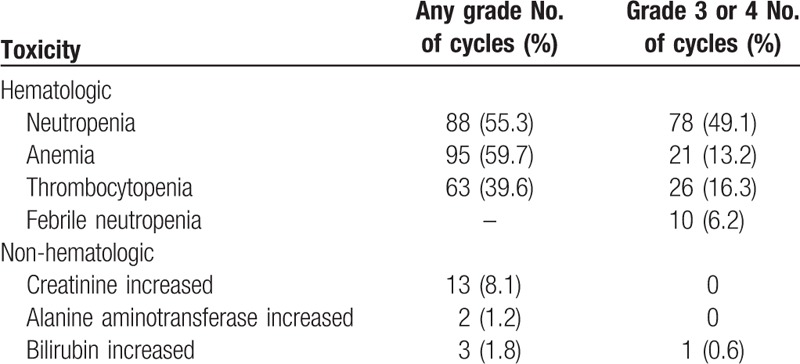

A total of 159 treatment cycles were administered (median, 4.0 cycles/patient; range, 1–6 cycles/patient). All patients reported some grade of hematological toxicity. The most frequent toxicity was anemia, with a rate of 59.7% for any grade and 13.2% for grade 3 or 4. The rate of neutropenia was 55.3% for any grade and 49.1% for grade 3 or 4, and that of thrombocytopenia was 39.6% for any grade and 16.3% for grade 3 or 4. The tolerable non-hematological toxicities were increased levels of creatinine in 8.1% of the cycles, alanine aminotransferase in 1.2% of the cycles, and bilirubin in 1.8% of any grade and 0.6% of grade 3 or 4. Febrile neutropenia developed in 10 (6.2%) cycles (Table 4).

Table 4.

Laboratory toxicities (total 159 cycles with combination of cisplatin and topotecan).

4. Discussion

Early-stage and locally advanced cervical cancers are managed with radical surgery or chemoradiotherapy. For the vast majority of patients with recurrent or advanced disease, palliative chemotherapy is the only treatment option.[12–15] Historically, cisplatin has been considered the most effective drug,[16] and numerous studies have assessed platinum-based combination chemotherapy regimens. Recently, based on the GOG 240 study, a combination of bevacizumab and platinum-based chemotherapy was accepted as the first-line treatment.[9] Patients with advanced or recurrent cervical cancer who progress to first-line chemotherapy have poor prognoses because of the overall unsatisfactory outcomes of further chemotherapy. Some studies of conventional chemotherapy involving capecitabine, vinorelbine, pemetrexed, or docetaxel have only shown partial efficacies of short duration, with an ORR of 8.7% to 15.4% and an OS of only approximately 7 months.[17–21] Novel agents such as lapatinib, pazopanib, and temsirolimus have been assessed as treatments for cervical cancer after the failure of standard chemotherapy. Pazopanib and lapatinib, which are multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors, had an ORR of 9% and 5%, a PFS of 4.5 months and 4.3 months, and an OS of 12.6 months and 9.8 months, respectively.[22] Temsirolimus, targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, had an ORR of 3% and a PFS of 3.5 months.[23] The efficacy of these novel agents was also shown to be unsatisfactory.

Topotecan is a specific S phase cytotoxic agent that cleaves double-stranded DNA during replication, which leads to cell death. Topotecan exerted a significant cytotoxic effect on several squamous cell lines of the cervix and vulva, including C-33, CaSki, and CAL-39.[24,25] Noda et al[26] first reported the anti-tumor activity of topotecan against cervical cancer, and clinical benefits were also reported for a combination of topotecan and cisplatin in patients with recurrent/persistent cervical cancer as first-line chemotherapy.[10] However, based on the GOG 204 study, a combination of paclitaxel and cisplatin showed better survival outcomes and quality of life compared with a combination of topotecan and cisplatin.[7] Therefore, the combination of cisplatin and topotecan is only one of several alternative treatment options and is not accepted as a first-line standard treatment for patients with recurrent/advanced cervical cancer. Previous studies of single-agent topotecan as second-line chemotherapy for cervical cancer have been reported, with an ORR of 12.5% to 17%, a PFS of 2.1 to 3.5 months, and an OS of 4.6 to 7.0 months.[25,27–29]

Our study is the first to report a clinical benefit of combination of topotecan and cisplatin as a second-line treatment for patients with advanced/recurrent/persistent cervical cancer. After this treatment, we found an ORR of 30.8%, a median PFS of 4.6 months, and a median OS of 14.1 months. The outcomes were better or comparable with those of previous reports evaluating topotecan-alone treatment as second-line or subsequent chemotherapy. In addition, patients who responded to previous chemotherapy before topotecan and cisplatin showed a significantly better ORR and DCR compared with those of non-responders. The median PFS (6.5 months vs 2.4 months) and median OS (15.4 months vs 9.2 months) were numerically better in the responder than in the non-responder group although their improvement did not reach statistical significance.

We evaluated laboratory toxicities because of the retrospective nature of this study. All patients reported some grade of hematological toxicity; 49.1% had grade 3/4 neutropenia, 13.2% had grade 3/4 anemia, 16.3% had grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia, and 6.2% had febrile neutropenia. These toxicity profiles were comparable with those of previously reported well-controlled trials using the same dosages of cisplatin and topotecan.[10] Most complications were manageable with antibiotics, G-CSF, and dose modifications and there was no difference of toxicity profile between the responders and the non-responders. There were 2 cases of treatment discontinuation due to toxicities; 1 patient showed severe pancytopenia and the other experienced prolonged thrombocytopenia. Both patients had previously undertaken curative radiotherapy for localized cervical cancer.

There were some limitations of the present study. First, it was a retrospective analysis and thus subject to potential selection biases. Second, the small sample size precluded definitive conclusions. Furthermore, only 1 patient was treated with a previous regimen including bevacizumab, which is currently the standard chemotherapy, because most enrolled patients were treated before the efficacy of this drug was confirmed. Hence, a prospective, well-designed, and controlled trial is needed, particularly involving patients treated with first-line chemotherapy involving bevacizumab.

In conclusion, the combination of topotecan and cisplatin was effective in patients with previously treated recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer. This combination is, therefore, a possible treatment for patients showing at least a partial response to prior chemotherapy.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Hyo Jin Lee, Young Bok Ko.

Data curation: Ik-Chan Song, Ji Young Moon.

Funding acquisition: Hyo Jin Lee.

Investigation: Young Bok Ko.

Methodology: Ji Young Moon.

Supervision: Hyo Jin Lee, Young Bok Ko.

Writing – original draft: Hyo Jin Lee, Ik-Chan Song, Ji Young Moon, Young Bok Ko.

Writing – review & editing: Hyo Jin Lee, Ik-Chan Song, Ji Young Moon, Young Bok Ko.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANC = absolute neutrophil count, CI = confidence interval, CR = complete response, DCR = disease control rate, DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor, GOG = Gynecologic Oncology Group, HPV = human papillomavirus, HR = hazard ratio, ORR = overall response rate, OS = overall survival, Pap = papanicolaou, PD = progressive disease, PFS = progression-free survival, PR = partial response, PS = performance status, RECIST = Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor, SD = stable disease, UNL = upper limit of normal.

JYM and I-CS have contributed equally to this work.

This work was in part supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP)(No. 2017R1A5A2015385) and a research fund of Chungnam National University.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Thaxton L, Waxman AG. Cervical cancer prevention: immunization and screening 2015. Med Clin North Am 2015;99:469–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2014. Cancer Res Treat 2017;49:292–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thigpen T, Shingleton H, Homesley H, et al. cis-Dichlorodiammineplatinum(II) in the treatment of gynecologic malignancies: phase II trials by the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer Treat Rep 1979;63:1549–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Omura GA, Blessing JA, Vaccarello L, et al. Randomized trial of cisplatin versus cisplatin plus mitolactol versus cisplatin plus ifosfamide in advanced squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Moore DH, Blessing JA, McQuellon RP, et al. Phase III study of cisplatin with or without paclitaxel in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Monk BJ, Sill MW, McMeekin DS, et al. Phase III trial of four cisplatin-containing doublet combinations in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4649–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Peiretti M, Zapardiel I, Zanagnolo V, et al. Management of recurrent cervical cancer: a review of the literature. Surg Oncol 2012;21:e59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, 3rd, et al. Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;370:734–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Long HJ, III, Bundy BN, Grendys EC, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of cisplatin with or without topotecan in carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:4626–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pignata S, Silvestro G, Ferrari E, et al. Phase II study of cisplatin and vinorelbine as first-line chemotherapy in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:756–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Monk BJ, Tewari KS, Koh WJ. Multimodality therapy for locally advanced cervical carcinoma: state of the art and future directions. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2952–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lorusso D, Petrelli F, Coinu A, et al. A systematic review comparing cisplatin and carboplatin plus paclitaxel-based chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133:117–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].duPont NC, Monk BJ. Chemotherapy in the management of cervical carcinoma. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 2006;4:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thigpen JT, Vance R, Puneky L, et al. Chemotherapy as a palliative treatment in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Semin Oncol 1995;22(2 Suppl 3):16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Boussios S, Seraj E, Zarkavelis G, et al. Management of patients with recurrent/advanced cervical cancer beyond first line platinum regimens: where do we stand? A literature review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2016;108:164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Garcia AA, Blessing JA, Darcy KM, et al. Phase II clinical trial of capecitabine in the treatment of advanced, persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with translational research: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol 2007;104:572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Garcia AA, Blessing JA, Vaccarello L, et al. Phase II clinical trial of docetaxel in refractory squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Am J Clin Oncol 2007;30:428–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Miller DS, Blessing JA, Bodurka DC, et al. Evaluation of pemetrexed (Alimta, LY231514) as second line chemotherapy in persistent or recurrent carcinoma of the cervix: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2008;110:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Muggia FM, Blessing JA, Method M, et al. Evaluation of vinorelbine in persistent or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2004;92:639–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Monk BJ, Mas Lopez L, Zarba JJ, et al. Phase II, open-label study of pazopanib or lapatinib monotherapy compared with pazopanib plus lapatinib combination therapy in patients with advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tinker AV, Ellard S, Welch S, et al. Phase II study of temsirolimus (CCI-779) in women with recurrent, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic carcinoma of the cervix. A trial of the NCIC Clinical Trials Group (NCIC CTG IND 199). Gynecol Oncol 2013;130:269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Boabang P, Kurbacher CM, Kohlhagen H, et al. Anti-neoplastic activity of topotecan versus cisplatin, etoposide and paclitaxel in four squamous cell cancer cell lines of the female genital tract using an ATP-Tumor Chemosensitivity Assay. Anticancer Drugs 2000;11:843–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Fiorica JV, Blessing JA, Puneky LV, et al. A Phase II evaluation of weekly topotecan as a single agent second line therapy in persistent or recurrent carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:285–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Noda K, Sasaki H, Yamamoto K, et al. Phase II trial of topotecan for cervical cancer of uterus (abstract). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:280. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bookman MA, Blessing JA, Hanjani P, et al. Topotecan in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol 2000;77:446–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].de Oliveira LN, Alves FVG, Mora PAR, et al. Topotecan use for second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer at brazilian national cancer institute (INCA). J Cancer Ther 2013;4:1095–9. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Coronel J, Cetina L, Candelaria M, et al. Weekly topotecan as second- or third-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer. Med Oncol 2009;26:210–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]