Abstract

Four cDNA clones named CPRD (cowpea responsive to dehydration) corresponding to genes that are responsive to dehydration were isolated using differential screening of a cDNA library prepared from 10-h dehydrated drought-tolerant cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) plants. One of the cDNA clones has a homology to 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (named VuNCED1), which is supposed to be involved in abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis. The GST (glutathione S-transferase)-fused protein indicates a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase activity, which catalyzes the cleavage of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid. The N-terminal region of the VuNCED1 protein directed the fused sGFP (synthetic green-fluorescent protein) into the plastids of the protoplasts, indicating that the N-terminal sequence acts as a transit peptide. Both the accumulation of ABA and expression of VuNCED1 were strongly induced by drought stress in the 8-d-old cowpea plant, whereas drought stress did not trigger the expression of VuABA1 (accession no. AB030295) gene that encodes zeaxanthin epoxidase. These results indicate that the VuNCED1 cDNA encodes a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase and that its product has a key role in the synthesis of ABA under drought stress.

Plants respond to water deficit and adapt to drought conditions by various physiological changes including transition in gene expression during water deficit. The mechanisms of drought response have been investigated most extensively in a model plant, Arabidopsis (Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 1997, 1999). In Arabidopsis, the drought signal is mediated through abscisic acid (ABA)-dependent and -independent pathways to regulate expression of genes that are involved in drought tolerance. For example, these gene products are thought to function in the accumulation of osmoprotectants, such as sugars and Pro, protein turnover, stress-signaling pathways, transcriptional regulation, and so on (Bray, 1997; Bohnert et al., 1995; Ingram and Bartels, 1996; Shinozaki and Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, 1997, 1999). On the contrary, the response of crops to drought stress has not been extensively studied. We have used cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) as a model crop plant for this subject. Molecular analysis of drought tolerance of cowpea may be useful to improve drought tolerance of other crops using transgenic plant technique.

We selected cowpea cv IT84S-2246-4 from many collected cultivars kept at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Nigeria. Cowpea cv IT84S-2246-4 possesses higher drought tolerance and produces a large yield of seeds compared to other cultivars in semi-arid areas (Singh, 1993). We previously reported drought-inducible genes isolated from cowpea cv IT84S-2246-4 using a differential screening method and characterized five of the cDNAs (CPRD8, CPRD14, and CPRD22 [Iuchi et al., 1996b], and CPRD12 and CPRD46 [Iuchi et al., 1996a]).

Here we report the isolation of two additional novel drought-inducible genes by differential screening. One of these genes, VuNCED1, encodes a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase that catalyzes the key step in ABA biosynthesis (Schwartz et al., 1997; Tan et al., 1997). We discuss the key role of the gene for the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase in drought-stress response and tolerance of cowpea.

RESULTS

Isolation of cDNA Clones That Correspond to Genes Induced by Dehydration

The cDNA library was constructed with poly(A+) RNA that had been isolated from 8-d-old plants after dehydration stress for 10 h. The cDNA library was differentially screened with cDNA prepared from poly(A+) RNA that had been isolated from unstressed plants and with cDNA prepared from poly(A+) RNA that had been isolated from plants after dehydration stress for 10 h. Thirty-six plaques gave a stronger hybridization signal with 32P-labeled cDNA from 10-h dehydrated plants. The plasmid regions of the 36 phage clones were excised in vivo and used to transform Escherichia coli cells. The cDNA fragments from the resultant plasmids were analyzed using the restriction map and the border DNA sequences of the cDNA fragments. From these analyses, we classified these 36 cDNA clones into six CPRD (cowpea responsive to dehydration) groups, i.e. CPRD51, CPRD52, CPRD65 (accession no. AB030293), CPRD72, CPRD76, and CPRD86 (accession no. AB030294). CPRD51 and CPRD52 had the same sequences as CPRD14 and CPRD22 (Iuchi et al., 1996b), respectively.

Dehydration-induced expression of the genes that corresponded to the four groups of CPRD clones was analyzed by northern-blot hybridization. The 8-d-old plants were removed from the soil and dehydrated for various periods up to 12 h. As controls, similar cowpea plants were transplanted to well-watered soil. Total RNA was then isolated from dehydrated or control plants for northern-blot hybridization. Figure 1 shows the time course of induction of the genes that corresponded to the CPRD clones in response to dehydration. Two CPRD genes, CPRD65 and CPRD86, were significantly induced by dehydration stress. The mRNAs corresponding to CPRD65 and CPRD86 began to accumulate within 2 h from the start of dehydration. The expression of two CPRD genes, CPRD72 and CPRD76, was not induced by dehydration stress using northern-blot hybridization (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Northern-blot analysis of the expression of the CPRD genes upon dehydration or rehydration. Total RNA was prepared from 8-d-old cowpea plants that had been dehydrated for 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 h or rehydrated for 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 24 h after dehydration for 10 h. Each lane was loaded with 10 μg of total RNA. The RNA was fractionated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and probed with 32P-labeled cDNA inserts of the CPRD clones.

Cowpea plants dehydrated for 10 h appeared wilted. These wilted plants showed recovery from wilting within 4 h after transfer to well-watered soil. After rehydration, the levels of CPRD65 and CPRD86 mRNAs decreased (Fig. 1). The CPRD65 and CPRD86 genes exhibited typical and significant responses to drought stress, namely, induction of the transcripts by dehydration and reduction of the level upon rehydration.

Sequence Analysis of the Drought-Inducible Gene

Since the CPRD65 cDNA was not full length, we screened again the same cDNA library with the partial CPRD65 cDNA as a probe, and then obtained its full-length cDNA. Figure 2 shows the deduced amino acid sequences of the full-length cDNA clone for CPRD65. The full-length CPRD65 cDNA consists of 2,432-bp nucleotides, including a 5′-flanking region of 125 bp and a 3′-flanking region of 468 bp (data not shown). One polyadenylation consensus sequence (AATAAA) was found in the 3′-flanking region. This sequence has a single open reading frame encoding a polypeptide of 612 amino acids with a calculated relative mass for the putative protein of 67.6 kD. Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of the CPRD65 protein with the protein database revealed an extensive homology with VP14 from maize (61% identity, Zea mays [Tan et al., 1997]) and LeNCED1 from tomato (69% identity, Lycopersicon esculentum [Burbidge et al., 1997b]) as shown in Figure 2. The putative CPRD65 protein seems to contain a transit polypeptide in its N-terminal region like the VP14 protein (Fig. 2). The N-terminal regions of CPRD65, VP14, and LeNCED1 have low sequence similarity, but structural similarity. We renamed CPRD65 as to VuNCED1 according to general nomenclature.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequences of the VuNCED1, VP14 (9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase from Zea mays; Schwartz et al., 1997), and LeNCED1 proteins (neoxanthin cleavage enzyme from Lycopersicon esculentum; Burbridge et al., 1997b). Dashes indicate gaps that were introduced to maximize alignment. Enclosed boxes indicate identical amino acids. Shadowed regions indicate similar amino acids.

Genomic Southern-Blot Analysis of the VuNCED1 Gene

To analyze genes that are related to the VuNCED1 gene in the cowpea genome, we carried out genomic Southern-blot hybridization under both low- and high-stringency conditions (Fig. 3). The VuNCED1 cDNA had no internal restriction site for EcoRI and XbaI and two internal restriction site for HindIII. We detected one hybridized band in the EcoRI and XbaI digest and two hybridized bands in the HindIII digest using the VuNCED1 cDNA as a probe. Additional faint hybridized bands were detected under low-stringency conditions. These results suggest that the VuNCED1 gene constitutes a small gene family with related genes.

Figure 3.

Southern-blot analysis of genomic DNA from cowpea cv 2246. Genomic DNA (10 μg per lane) was digested with EcoRI (E), HindIII (H), and XbaI (X), fractionated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane. The filter was allowed to hybridize with a 32P-labeled fragment of the VuNCED1 cDNA. High and Low represent high- and low-stringency hybridization conditions (see “Materials and Methods”), respectively. The size of marker fragments of DNA is indicated in kb.

Northern-Blot Analysis of the VuNCED1 Gene

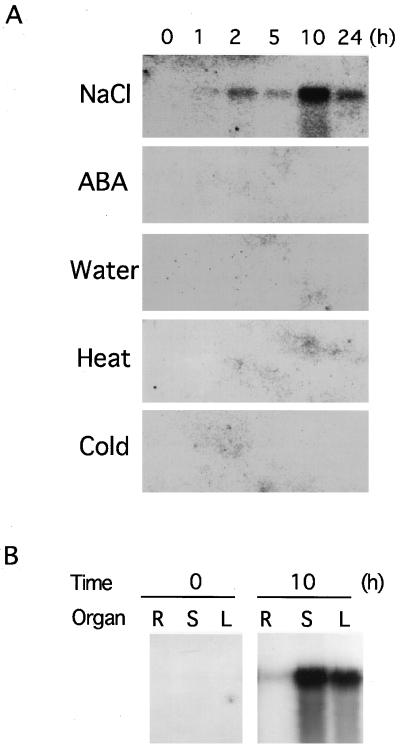

We analyzed the effects of various environmental stresses on the expression of the VuNCED1 gene, and found that the gene was strongly induced under a high-salt condition, but not by cold or heat stress (Fig. 4A). The induction of the VuNCED1 gene was not detected by exogenous ABA application or water treatment.

Figure 4.

A, Northern-blot analysis of the induction of the VuNCED1 gene by high salinity (NaCl), the application of ABA (ABA), water treatment (Water), high temperature (Heat), and low temperature (Cold). Total RNA was isolated from the cowpea plants at the indicated hours after the treatment. Each lane was loaded with 10 μg of total RNA. The number above each lane indicates the duration (h) of treatment. B, Northern-blot analysis of the VuNCED1 gene without or with 10-h dehydrated treatment. Each lane was loaded with 10 μg of total RNA isolated from leaves (L), stems (S), and roots (R) from cowpea cv 2246. The RNA was fractionated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and probed with 32P-labeled cDNA inserts of the VuNCED1 cDNA.

To determine the organ specificity of the expression of the VuNCED1 gene under drought stress, we performed northern-blot hybridization of total RNA prepared from leaves, stems, or roots under a normal or drought condition (Fig. 4B). The VuNCED1 transcript was strongly induced in stems and leaves by drought treatment, but less in roots.

Enzymatic Properties of the Bacterially Expressed VuNCED1 Protein

The deduced amino acid sequence of the VuNCED1 gene has high homology with that of the maize Vp14 gene encoding a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid cleavage enzyme (Fig. 2). To examine whether the VuNCED1 gene encodes a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, we analyzed the biochemical properties of the recombinant VuNCED1 protein expressed in E. coli. A DNA fragment for the VuNCED1 coding region (amino acid nos. 1–612; Fig. 1) was amplified by PCR and fused to the GST (glutathione S-transferase) gene in frame using the pGEX4T-1 (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) to construct a chimeric plasmid pGST-VuNCED1. The GST-VuNCED1 protein was overexpressed in E. coli and purified from the crude cell extract using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia Biotech).

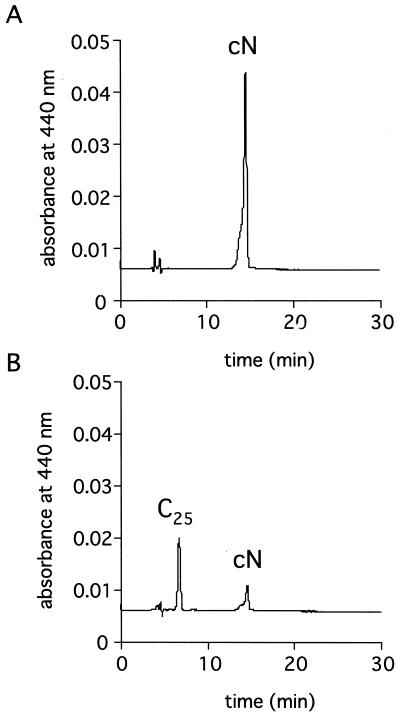

We then examined whether the purified GST-VuNCED1 recombinant protein digests 9′-cis-neox-anthin, all-trans-violaxanthin, and 9-cis-violaxanthin to produce xanthoxin. As shown in Figure 5, the predicted C25-product was detected in the hexane extract of reaction mixture with the GST-VuNCED1 protein and 9′-cis-neoxanthin by HPLC analysis. Another product of cleavage reaction, xanthoxin, was detected in the ethyl acetate extract by HPLC analysis and it was identified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis in which ions characteristic for xanthoxin were observed. The ions and their relative intensities were: m/z 250 (4), 168 (32), 149 (77), 107 (61), and 95 (100). Xanthoxin and predicted C25-product were also formed from 9-cis-violaxanthin (data not shown) but not from all-trans-violaxanthin. These results were not affected by the treatment with thrombin, which separates the GST-VuNCED1 recombinant protein into GST and VuNCED1 portion.

Figure 5.

HPLC profiles of carotenoid metabolites of GST (A) or the GST-VuNCED1 recombinant protein (B). The reaction mixture contain 9′-cis-neoxanthin as substrate. cN, 9′-cis-Neoxanthin; C25, predicted C25-product.

Analysis of the N-Terminal Region of the VuNCED1 Protein as a Transit Peptide in Arabidopsis Protoplasts

The N-terminal region of the VuNCED1 protein has typical structural features of transit peptides that are involved in chloroplast targeting. This structural feature of the VuNCED1 protein suggests that the mature VuNCED1 protein is localized in plastids. To analyze the role of its N-terminal region as a transit peptide, we constructed a chimeric gene, 35S::VuNCED1N-sGFP, that encodes the N-terminal region of the VuNCED1 protein (1–148 amino acid nos.; Fig. 1) between the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and the sGFP (synthetic green-fluorescent protein) gene of the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (Chiu et al., 1996). The 35S::VuNCED1N-sGFP fusion construct and its control construct, 35S::sGFP, were introduced into protoplasts of Arabidopsis leaves by the DNA-transfection method (Abel and Theologis, 1994). Two to 4 d after the transformation, we observed the protoplasts by fluorescent microscopy. As shown in Figure 6, green fluorescence was localized in plastids when 35S::VuNCED1N-sGFP was transiently expressed in protoplasts. On the other hand, green fluorescence was detected mainly in the cytoplasm but not in plastids using the 35S::sGFP construct. These results suggest that the N-terminal region of the VuNCED1 protein functions as a transit peptide to target the VuNCED1 protein into plastids.

Figure 6.

Plastid targeting of the VuNCED1N-sGFP chimeric protein in protoplasts. Constructs carrying the 35S::sGFP (A, C, and E) or the 35S::VuNCED1N-sGFP chimeric constructs (B, D, and F) were transfected into Arabidopsis protoplasts using polyethylene glycol. Transfected protoplasts were observed by optical microscopy (A and B) or fluorescent microscopy with an interference filter type red (C and D) or green (E and F).

Accumulation of ABA during Dehydration Stress in 8-d-Old Cowpea Plants

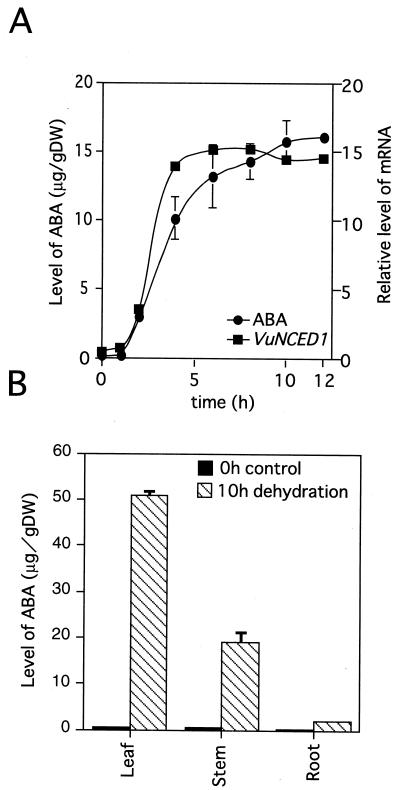

We measured the accumulation of endogenous ABA level in 8-d-old cowpea plant during dehydration conditions. As shown in Figure 7A, ABA began to accumulate within 2 h after the beginning of dehydration. The level of ABA in 10-h dehydrated plants was 140 times higher than that in unstressed control plants. The timing of accumulation of the VuNCED1 mRNA was earlier than that of ABA accumulation (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

The relationship between the accumulation of ABA and the expression of the VuNCED1 gene during dehydration (A). The accumulation of ABA in cowpea plants during dehydration treatment after separation of organs (B). The radioactivity retained on the nylon filter in Figure 1 was quantified and plotted as shown. The procedure for quantification of ABA is described in “Materials and Methods.” Error bars show se. The experiment was repeated three times.

The expression of the VuNCED1 gene was strongly induced by drought stress in leaves and stems, but slightly in roots (Fig. 4B). We examined the relation between the expression of the VuNCED1 gene and the accumulation of endogenous ABA under drought stress. The 8-d-old cowpea plants were separated into leaves, stems, and roots, and then dehydrated. The endogenous ABA levels in these organs were measured before or after dehydration treatment. As shown in Figure 7B, endogenous ABA was dramatically increased by drought stress in leaves and stems but slightly increased in roots. The tissue-specific pattern of ABA accumulation under drought stress was consistent with that of the expression of the VuNCED1 gene as shown in Figures 4B and 7B.

Analysis of Xanthophylls in Cowpea Leaf

Xanthophylls in cowpea leaf were analyzed to find possible substrates for the VuNCED1 protein. all-trans-Violaxanthin, all-trans-neoxanthin, and 9′-cis-neoxanthin were detected as major xanthophylls in cowpea leaf by optical spectroscopic analysis, and 9-cis-violaxanthin was detected as a minor component (data not shown). The levels of all-trans-violaxanthin, 9-cis-violaxanthin, all-trans-neoxanthin, and 9′-cis-neoxanthin were 1.3, 0.059, 0.98, and 0.69 μg g−1 under normal growth conditions, respectively, and did not change significantly under drought conditions.

Characterization of a Gene for Zeaxanthin Epoxidase from Cowpea

To examine whether the epoxidation step of zeaxanthin, an earlier step of ABA biosynthesis, is influenced under drought stress, we isolated a cDNA for zeaxanthin epoxidase (named VuABA1) from the cowpea cDNA library prepared from dehydrated plants, and analyzed its gene expression under drought stress. The VuABA1 cDNA consists of 2,349-bp nucleotides and has a single open reading frame encoding a polypeptide of 612 amino acids with a calculated relative mass for the putative protein of 67 kD. Based on the comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence with a protein database, the VuABA1 protein revealed an extensive homology with zeaxanthin epoxidase from tobacco (68% identity, Nicotiana plumbaginifolia [Marin et al., 1996]), Arabidopsis (68% identity, this work, accession no. AB030296), and tomato (67% identity, Lycopersicon esculentum [Burbidge et al., 1997a]).

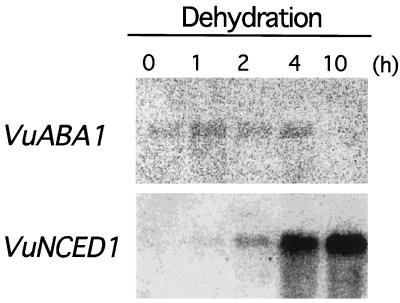

We analyzed the expression of the VuABA1 gene under drought conditions by northern-blot hybridization. Total RNA was isolated from cowpea plants with or without dehydration treatment and blotted on nylon membrane. Northern hybridization analysis obviously indicated that the expression of the VuNCED1 gene is significantly induced by drought whereas that of the VuABA1 gene is not (Fig. 8). This observation suggests that the key role of the VuNCED1 gene in ABA biosynthesis under drought stress in cowpea.

Figure 8.

Northern-blot analysis of the expression of the VuABA1 and the VuNCED1 genes upon dehydration. Total RNA was prepared from 8-d-old cowpea plants that had been dehydrated for 0, 1, 2, 4, and 10 h. Each lane was loaded with 10 μg of total RNA. The RNA was fractionated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and probed with 32P-labeled DNA inserts of the VuABA1 and the VuNCED1 cDNAs.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported the isolation and characterization of nine drought-inducible genes (CPRD) from 4-week-old cowpea plants by differential screening to elucidate the molecular response of cowpea plants to drought stress (Iuchi et al., 1996a, 1996b). In the present study, we isolated two novel cDNAs by another series of differential screening. Both genes were significantly induced by drought stress. Their mRNA levels decreased significantly by rehydration after 10-h dehydration (Fig. 1).

The CPRD65 cDNA revealed sequence homology with the 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, which is involved in ABA biosynthesis (Fig. 2). The corresponding gene was named as VuNCED1. The recombinant VuNCED1 protein showed 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase activity (Fig. 5), and consistent with the activity of maize VP14 (Schwartz et al., 1997), both 9′-cis-neoxanthin and 9-cis-violaxanthin were good substrates for VuNCED1. Since endogenous level of 9′-cis-neoxanthin was much higher than that of 9-cis-violaxanthin in cowpea leaf, 9′-cis-neoxanthin may act as the major immediate precursor of xanthoxin in cowpea leaf.

The amino-terminal region of the VuNCED1 protein has low homology with those of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenases from maize and tomato, and is thought to be a transit peptide involved in chloroplast targeting based on its structural feature. However, the localization of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase in plastids has not been proved, yet. We demonstrated that the N-terminal region of the VuNCED1 protein functions as a transit peptide for plastid targeting (Fig. 6). Epoxy-carotenoids localized in plastids and the oxidative cleavage reaction of epoxy-carotenoids is supposed to occur in plastids (Zeevaart and Creelman, 1988). Our findings indicate that 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase is targeted into plastids and functions in the plastid to produce ABA.

In an 8-d-old plant, biosynthesis of endogenous ABA was obviously induced by drought stress within 2 h after drought treatment (Fig. 7A). The VuNCED1 gene was significantly induced by drought stress within 2 h, but the VuABA1 gene encoding zeaxanthin epoxidase was not (Fig. 8). The timing of the induction of the VuNCED1 gene is slightly earlier than that of ABA accumulation under drought stress (Fig. 7A). Biochemical studies have indicated that the key step in the ABA biosynthesis is the cleavage of neoxanthin (Kende and Zeevaart, 1997). The accumulation of ABA by drought stress has been also speculated to be regulated at the transcriptional level based on experiments using transcriptional inhibitors (Guerrero and Mullet, 1986; Stewart et al., 1986). The induction of genes for 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase by drought stress has been observed in maize, tomato, Arabidopsis, and bean (Burbidge et al., 1997b; Tan et al., 1997; Neill et al., 1998; Qin and Zeevaart, 1999). Moreover, it has been reported that the enzyme activity that catalyzes the reaction from xanthoxin to ABA is unchanged under drought conditions (Sindhu and Walton, 1987). It is noteworthy that the level of 9′-cis-neoxanthin, the substrate for the VuNCED1 protein, is high enough to produce an excess amount of ABA even under non-drought conditions. Our results also indicate that the induction of a gene for 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase is mainly responsible for ABA biosynthesis under drought conditions.

In dehydrated cowpea plants, the VuNCED1 gene is strongly expressed in leaves and stems but not in roots (Fig. 4B). Endogenous ABA also accumulates mainly in leaves and stems under drought conditions (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that ABA is mainly produced in leaves but not in roots in dehydrated cowpea, and that ABA produced in leaves mainly triggers stomata closure.

In maize, strong expression of the Vp14 gene was detected in the roots even under non-stress conditions. The mRNA of tomato Vp14 homolog has been detected before and after drought stress (Burbidge et al., 1997b). By contrast, the VuNCED1 mRNA was not detected before stress treatment (Fig. 1). Thus, the VuNCED1 protein may mainly function under drought and high salt conditions but not under normal growth condition. Five independent sequences encoding VP14 homologs from Arabidopsis have been found in the DNA database (accession nos. AL021710, AL021687, AJ005813, AB028617, and AB028621). The cowpea genome also has a small gene family of the VuNCED1 gene based on genomic Southern-blot analysis (Fig. 3). In cowpea, other VuNCED1 homologs may function under normal growth conditions.

In conclusion, we showed that cowpea drought-inducible VuNCED1 gene encodes the 9-cis-epoxy-carotenoid dioxygenase, a key enzyme involved in ABA biosynthesis, and its product is localized in plastids. Our results strongly suggest that the VuNCED1 protein is mainly involved in the ABA biosynthesis under drought stress. Analysis of transgenic plants in which the VuNCED1 gene is overexpressed or suppressed by antisense RNA should give us more information on its function in ABA biosynthesis under stressed condition.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Growth

Seeds of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata cv IT84S-2246-4) were sown in pots and grown for 8 d in a greenhouse with a photoperiod of 16 h supplemented with artificial lighting, temperature of 25°C, and appropriate watering.

Dehydration Treatment

For dehydration treatment, plants were removed from the soil carefully to avoid injury, weighed, and subjected to dehydration on 3MM paper (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) at room temperature and approximately 60% humidity under dim light (300 lux). The relative weight was reached to 55% of initial weight after 5-h dehydration treatment. For the control, plants were removed from the soil as dehydration treatment, and immediately transplanted in well-watered soil that was maintained under the same condition for dehydration treatment.

Stress and Phytohormone Treatments

For high salt, ABA, and water treatments, plants were removed from the soil in the same way as in the dehydration treatment, and then hydroponically grown in solution containing 250 mm NaCl, 100 μm ABA, and deionized water, respectively. For heat- and cold-stress treatments, plants in pots were transferred to incubators at 40°C and 4°C, respectively. In each case, the plants were subjected to the stress treatments for 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 24 h. After heat- or cold-stress treatment, the plants were removed from the pot, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Preparation and Screening of a cDNA Library from Dehydrated Plants

Whole plants were harvested, washed gently to remove soil from the roots, and then subjected to dehydration on Whatman 3MM paper at room temperature and approximately 60% humidity under dim light. Whole plants (20 g), which either had or had not been dehydrated, were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was prepared as described previously (Nagy et al., 1988). Poly(A+) RNA was isolated by two passages of the total preparation of RNA over a column of oligo(dt) cellulose, as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). About 2% of the RNA that was initially applied to the column was recovered in the poly(A+) RNA fraction. Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from poly(A+) RNA with cDNA Synthesis System Plus (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo). Using a cDNA Cloning System from Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, we prepared a cDNA library from the cDNA. We screened 1 × 104 plaques of the primary cDNA library by the plaque hybridization method of Sambrook et al. (1989).

Isolation of Zeaxanthin Epoxidase Gene Using Reverse Transcriptase-PCR

The cDNA for zeaxanthin epoxidase gene from Arabidopsis was isolated from a cDNA library using expression sequence tag fragments (accession no. T45502) as a probe and named AtABA1 (accession no. AB030296).

Total RNA was isolated from cowpea plants as described above. Two synthetic oligonucleotides were designed using regions conserved between AtABA1 and ABA2 from tobacco (Marin et al., 1996). The partial DNA fragment of putative zeaxanthin epoxidase from cowpea was amplified by reverse transcriptase-PCR using the primers: 5′-GTNGCNGGNGGNGGNATHGGNGG-3′ and 5′-ACYTTNCGYATGGTRACGTARAA-3′ (H means A, C, and T; Y means C and T; and R means A and G) and cloned into pBluescript II SK+ cloning vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). A full-length cDNA of putative zeaxanthin epoxidase gene, designated VuABA1, was isolated by screening the cDNA library that was constructed from dehydrated-cowpea plants, using the partial DNA fragment as a probe.

Expression of a GST-CPRD65 Fusion Protein

The DNA of the CPRD65 protein was amplified by PCR using primers: 5′-ATTGAATTCATGCCTTCAGCTTCA-AAC-3′ and 5′-ATTGGATCCCAAAAGCTACACGCTGG-TCCCC-3′. The PCR fragment was inserted into the EcoRV site of pBluescript II SK+ cloning vector (Stratagene). The DNA fragment was inserted in the EcoRI and XhoI site of pGEX4T-1 (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) to yield pGST-CPRD65. Cells of Escherichia coli strain JM109 were transformed with pGST-CPRD65 or pGEX4T-1 and grown in L broth at 37°C. When OD600 reached about 0.5, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added and incubation was continued for 12 h at 17°C. The cells were harvested, washed, and suspended in extraction buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mm MgCl2, 5% [v/v] glycerol, 0.1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.1 mm dithiothreitol). The procedures for the purification of the fusion protein and digestion with thrombin were performed according to the instruction manual for the GST gene fusion system (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech). The protein concentration was determined with a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Assay of 9-cis-Epoxycarotenoid Dioxygenase Activity

The assay procedures for 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid cleavage enzyme have been described (Schwartz et al., 1997). 9′-cis-Neoxanthin and all-trans-violaxanthin were prepared from spinach leaves. 9-cis-Violaxanthin was prepared from orange peel. The reaction mixture (100 μL) contained 100 mm bis-Tris (2-[bis(hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)-1-propane-1,3-diol; pH 6.7), 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100, 10 mm ascorbate, 5 mm FeSO4, and protein sample. The reaction was allowed to proceed at room temperature for 1 h. After addition of 1 mL of water, the reaction mixtures were extracted with n-hexane (1 mL × 2) and then ethyl acetate (1 mL × 2). The n-hexane fraction was concentrated and submitted to HPLC analysis on a column (Senshu Pak ODS H 3151; 150-mm length, 8-mm i.d., Senshu Scientific, Tokyo). The column was eluted with a linear gradient between solvent A (85% [v/v] aqueous methanol) and solvent B (chloroform and methanol, 1:1) at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The concentration of solvent B was increased from 10% to 50% in 25 min, and kept at 50% for 5 min. The elution was monitored with a UV/visible detector at 440 nm. The ethyl acetate fraction was purified with HPLC on a column (Senshu Pak ODS H 3151; 150-mm length, 8-mm i.d.). The column was eluted with 50% (v/v) aqueous methanol at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min, and elution was monitored with a UV detector at 260 nm. The predicted xanthoxin fraction was collected and submitted to GC-MS analysis. In each step, samples were shielded from light as much as possible.

ABA Analysis

Samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen and extracted with 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol twice. After addition of [2H3]ABA, the extracts were concentrated, and submitted to a conventional solvent fractionation procedure to give an acidic-ethyl acetate soluble fraction. It was purified using Bond Elut cartridge columns (C18 and DEA, Varian, Harbor City, CA) by the procedure reported previously (Wijayanti et al., 1995). Purified samples from undesiccated plants were then subjected to HPLC analysis with a Senshu Pak ODS-2101-N column (100-mm length, 6-mm i.d., Senshu Scientific Co., Tokyo). The analytical conditions were the same as reported previously (Wijayanti et al., 1995). Samples thus purified were methylated with etherial diazomethane and submitted to GC-selected ion monitoring analysis.

Xanthophyll Analysis

Samples were extracted with acetone twice, and the extracts were concentrated, dissolved in 80% (v/v) methanol (1 mL), and loaded onto a Bond Elut C18 column (1 g). The column was washed with additional 4 mL of 80% (v/v) aqueous MeOH, and xanthophylls were eluted with 5 mL of methanol:water:chloroform (71:9:20). The eluate was concentrated and applied to HPLC analyses with columns of Senshu Pak ODS-H-3151 (150-mm length, 8-mm i.d.) and Senshu Pak Silica-2251-S (250-mm length, 6-mm i.d.). In ODS-HPLC, the column was eluted with a linear gradient between solvent A (85% [v/v] aqueous methanol) and solvent B (chloroform and methanol, 1:1) at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. The concentration of solvent B was changed from 10% to 50% in 45 min. For silica-HPLC, we used a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min, and a linear gradient of solvent B concentration from 10% to 100% in 60 min where solvent A was ethyl acetate:n-hexane (1:1) and solvent B is ethyl acetate. The identity of xanthophylls was determined from their visible and UV spectroscopic data (Parry et al., 1990).

GC-MS Analysis

An AUTOMASS mass spectrometer (JEOL Ltd., Akishima, Japan) equipped with a 5890 gas chromatograph (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) was used for the analysis. The analytical conditions were as follows: ionization, EI 70 eV; column, DB-5 (15-m length, 0.25-mm i.d., 0.25-mm film thickness, J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA); carrier gas, He (1 mL min−1); injection temperature, 250°C; transfer line temperature, 250°C; initial oven temperature, 80°C. Starting 1 min after injection, the oven temperature was increased to 200°C at a rate of 5°C min−1 followed by further increment to 230°C at a rate of 5°C min−1. ABA was quantified by the area ratio between m/z 190 (endogenous) and 193 (internal standard).

Transit Expression of the sGFP Protein in Protoplasts

The DNA for the N-terminal peptide (1–148 amino acids) of the CPRD65 protein was amplified by PCR using primers: 5′-ATATATCTAGAATGCCTTCATCAGCTTCAAACACTT- GG-3′ and 5′-ATATAGGATCCCTCCGGCACCGGCGCGA- AGTTCCCG-3′. The PCR fragment was inserted into the pBluescript II SK+ cloning vector (Stratagene). The DNA fragment was inserted into the site between 35S-promoter and sGFP gene on transit expression vector (Chiu et al., 1996). The preparation, DNA transfection, and incubation of the Arabidopsis protoplasts were performed as previously described (Abel and Theologis, 1994).

Southern and Northern Analysis

Genomic Southern analysis was performed as described elsewhere (Sambrook et al., 1989). Ten milligrams of genomic DNA digested with restriction endonuclease was fractionated in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and blotted onto a nylon filter. The filter was hybridized with 32P-labeled fragments in 30% (w/v) formamide, 6× SSC, 5× Denhardt's solution, and 100 μg/mL of denatured salmon sperm DNA at 42°C. The filter was washed twice with 0.1× SSC, 0.1% (w/v) SDS at 60°C for 15 min (high stringency), or 0.5× SSC, 0.5% (w/v) SDS at 37°C for 15 min (low stringency), and subjected to autoradiography.

Total RNA was isolated according to the method described by Nagy et al. (1988). Total RNA was fractionated in a 1% (w/v) agarose gel containing formaldehyde and was blotted onto a nylon filter (Sambrook et al., 1989). The filter was hybridized with 32P-labeled fragments in 50% (v/v) formamide, 5× SSC, 25 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, 10× Denhardt's solution, and 250 μg/mL of denatured salmon sperm DNA at 42°C. The filter was washed twice with 0.1× SSC, 0.1% (v/v) SDS at 60°C for 15 min and subjected to autoradiography.

Analysis of DNA Sequences

Plasmid DNA templates were prepared using the Automatic Plasmid Isolation System model PI-100 (Kurabo, Osaka), and sequenced using the DNA Sequencer model 373A (ABI, San Jose, CA). Nucleotide sequences and amino acid sequences were analyzed using a GeneWorks Software System (Intelligenetics, Mountain View, CA), Sequencher 3.0 (Hitachi, Tokyo), and the University of Wisconsin Genetic Computer Group (GCG) program.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Kazuo Nakashima (Japan International Research Center for Agricultural Sciences) for his help in some experiments. We also thank Ikuyo Furukawa and Hiroko Kanahara for their excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Program for Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences, the Special Coordination Fund of the Science and Technology Agency of the Japanese Government, by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan, and by the Special Postdoctoral Researchers Program from the Science and Technology Agency of the Japanese Government (to S.I.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Abel S, Theologis A. Transient transformation of Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts: a versatile experimental system to study gene expression. Plant J. 1994;5:421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1994.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert HJ, Nelson DE, Jensen RG. Adaptations to environmental stresses. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1099–1111. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray EA. Plant responses to water deficit. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge A, Grieve T, Terry C, Corlett J, Thompson A, Taylor I. Structure and expression of a cDNA encoding zeaxanthin epoxidase, isolated from a wilt-related tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) J Exp Bot. 1997a;48:1749–1750. [Google Scholar]

- Burbidge A, Grieve TM, Jackson A, Thompson A, Taylor IB. Structure and expression of a cDNA encoding a putative neoxanthin cleavage enzyme (NCE) isolated from a wilt-related tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) library. J Exp Bot. 1997b;47:2111–2112. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu W, Niwa Y, Zeng W, Hirano T, Kobayashi H, Sheen J. Engineered GFP as a vital reporter in plants. Curr Biol. 1996;6:325–330. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00483-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero F, Mullet JE. Increased abscisic acid biosynthesis during plant dehydration requires transcription. Plant Physiol. 1986;80:588–591. doi: 10.1104/pp.80.2.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J, Bartels D. The molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:377–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Urao T, Shinozaki K. Characterization of two cDNAs for novel drought-inducible genes in the highly drought-tolerant cowpea. J Plant Res. 1996a;109:415–424. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iuchi S, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Urao T, Terao T, Shinozaki K. Novel drought-inducible genes in the highly drought-tolerant cowpea: cloning of cDNAs and analysis of their gene expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996b;37:1073–1082. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kende H, Zeevaart JAD. The five classical plant hormones. Plant Cell. 1997;9:1197–1210. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin E, Nussaume L, Quesada A, Gonneau M, Sotta B, Hugueney P, Frey A, Marion-Poll A. Molecular identification of zeaxanthin epoxidase of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia, a gene involved in abscisic acid biosynthesis and corresponding to the ABA locus of Arabidopsis thaliana. EMBO J. 1996;15:2331–2342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy F, Kay SA, Chua N-H. Analysis of gene expression in transgenic plants. In: Gelvin SB, Schilperoort RA, Verma DPS, editors. Plant Molecular Biology Manual, B4. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1988. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Neill SJ, Burnett EC, Desikan R, Hancock JT. Cloning of a wilt-responsive cDNA from an Arabidopsis thaliana suspension culture cDNA library that encodes a putative 9-cis-epoxy-carotenoid dioxygenase. J Exp Bot. 1998;49:1893–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Parry AD, Babiano MJ, Horgan R. The role of cis-carotenoids in abscisic acid biosynthesis. Planta. 1990;182:118–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00239993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X, Zeevaart JA. The 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid cleavage reaction is the key regulatory step of abscisic acid biosynthesis in water-stressed bean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15354–15361. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SH, Tan BC, Gage DA, Zeevaart JA, McCarty DR. Specific oxidative cleavage of carotenoids by VP14 of maize. Science. 1997;276:1872–1874. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Gene expression and signal transduction in water-stress response. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:327–334. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Molecular responses to drought stress. In: Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, editors. Molecular Responses to Cold, Drought, Heat and Salt Stress in Higher Plants. R.G. Austin, TX: Landes Company; 1999. pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu RK, Walton DC. Conversion of xanthoxin to abscisic acid by cell-free preparations from bean leaves. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:916–921. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.4.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BB. The cowpea breeding section of the archivalt (1988–1992) of the grain legume improvement program. Ipadan, Nigeria: International Institute of Tropical Agriculture; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart CR, Voetberg G, Rayapati PJ. The effects of benzyladenine, cycloheximide, and cordycepin on wilting-induced abscisic acid and proline accumulations and abscisic acid- and salt-induced proline accumulation in barley leaves. Plant Physiol. 1986;82:703–707. doi: 10.1104/pp.82.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BC, Schwartz SH, Zeevaart JA, McCarty DR. Genetic control of abscisic acid biosynthesis in maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12235–12240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijayanti L, Kobayashi M, Fujioka S, Yoshizawa K, Sakurai A. Identification and quantification of abscisic acid, indole-3-acetic acid and gobberellins in phloem exudates of Pharbitis nil. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1995;59:1533–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Zeevaart JAD, Creelman RA. Metabolism and physiology of abscisic acid. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1988;39:439–473. [Google Scholar]