Abstract

Background

Developing successful interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain requires valid, responsive, and reliable outcome measures. The Minneapolis VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program completed a focused evidence review on key psychometric properties of 17 self-report measures of pain severity and pain-related functional impairment suitable for clinical research on chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Methods

Pain experts of the VA Pain Measurement Outcomes Workgroup identified 17 pain measures to undergo systematic review. In addition to a MEDLINE search on these 17 measures (1/2000–1/2017), we hand-searched (without publication date limits) the reference lists of all included studies, prior systematic reviews, and—when available—Web sites dedicated to each measure (PROSPERO registration CRD42017056610). Our primary outcome was the measure’s minimal important difference (MID). Secondary outcomes included responsiveness, validity, and test-retest reliability. Outcomes were synthesized through evidence mapping and qualitative comparison.

Results

Of 1635 abstracts identified, 331 articles underwent full-text review, and 43 met inclusion criteria. Five measures (Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), SF-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), and Visual Analog Scale (VAS)) had data reported on MID, responsiveness, validity, and test-retest reliability. Seven measures had data reported on three of the four psychometric outcomes. Eight measures had reported MIDs, though estimation methods differed substantially and often were not clinically anchored.

Conclusions

In this focused evidence review, the most evidence on key psychometric properties in chronic musculoskeletal pain populations was found for the ODI, RMDQ, SF-36 BPS, NRS, and VAS. Key limitations in the field include substantial variation in methods of estimating psychometric properties, defining chronic musculoskeletal pain, and reporting patient demographics.

Trial Registration

Registered in the PROSPERO database: CRD42017056610

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-018-4327-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: chronic pain, pain, psychometrics, systematic review, measurement

INTRODUCTION

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is a major source of disability and morbidity in the USA,1 and affects approximately 60% of Veterans with chronic health conditions in Veterans Health Administration (VHA) primary care.2 Management remains challenging, and groups ranging from pain expert coalitions to the National Institutes of Health and the Institute of Medicine have called for more focused and strategic pain therapy research.3 As these groups note, successful development and testing of interventions to improve chronic musculoskeletal pain depends on the use of valid, reliable, and responsive measures of pain domains.

Existing pain outcome measures often span multiple physical, emotional, and social domains. To guide development and use of these measures, experts and stakeholders have formed such initiatives as Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT), the Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations, Innovations, Opportunities, and Networks (ACTTION) public-private partnership with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the associated Initiative on Methods, Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT), and the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain. These groups have published several reviews and compiled recommendations suggesting that pain outcome studies measure multiple domains via multiple modes of assessment.4–9 These groups have identified both pain intensity or severity (hereafter “severity”) and pain-related impairment of physical function (hereafter “functional impairment”) as key domains for study, as these reflect both pain symptoms and pain’s impact on people’s daily lives.4,8 Functional impairment has been identified as a priority concern for patients10 and is an increasingly common primary outcome domain alongside pain severity. Self-report measures remain the gold standard mode of assessing core pain outcomes, as they reflect subjective pain experience, and as existing observer- and laboratory-based pain measures do not consistently reflect clinically meaningful changes in key pain domains.4,6,11

The Department of Veterans Affairs 2016 State of the Art (SOTA) Conference on non-pharmacological approaches to chronic musculoskeletal pain management recognized the value of adopting a consistent core set of outcome measures for future chronic pain research. For example, such a core could facilitate cross-study comparisons of intervention effectiveness and other findings. To inform their choice of key measures, the VA Pain Measurement Outcomes Workgroup requested an evidence review focused on describing existing research on key psychometric properties of 17 commonly used self-report measures of pain severity and pain-related functional impairment. Research on such psychometric properties would not provide the only criterion for selecting core measures,12 but can be seen as a basic requirement of candidates for wide implementation. Our review addressed the following key question: Which of the 17 self-report pain measures nominated by the VA Pain Measurement Outcomes Workgroup had sufficient psychometric evidence to consider their adoption for use as core outcome measures in future clinical research? The findings in this manuscript are based on a VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program report available online.13

METHODS

In conjunction with the topic nominators’ expert input, we developed a protocol for this review (registered in the PROSPERO database: CRD42017056610) and identified the populations of interest, study inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1), and our primary and secondary psychometric outcomes. The topic nominators requested a focus on chronic, non-traumatic musculoskeletal pain, which was defined as musculoskeletal pain of at least a 3-month duration. There was a particular interest in measures that had been used in Veteran populations and in multidimensional measures that assessed both pain severity and pain-related functional impairments, such as activity limitations and interference with physical function.

Table 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria (1) Studies of adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain of at least a 3-month duration (or described as “chronic” by the study authors); if the study included multiple types of pain, at least 75% of the population must have had chronic musculoskeletal pain unless results were reported separately for the chronic musculoskeletal pain group (2) Reporting on self-reported measures of pain intensity or pain-related functioning, limited to the following: Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS) Hip Osteoarthritis Outcomes Scale (HOOS) Knee Osteoarthritis Outcomes Scale (KOOS) McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI, WHYMPI) Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) PEG (assesses [P] pain intensity, [E] enjoyment of life, and [G] general activity) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System - Pain Interference (PROMIS-PI) Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) SF-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS) Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) Wong Faces Scale (3) Reporting any or all outcomes of interest: minimal important difference (primary outcome), responsiveness, validity (concurrent and/or discriminant), test-retest reliability Exclusion criteria (1) Studies of patients with conditions often associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain unless the study specified that the patients had chronic musculoskeletal pain (e.g., radiologically defined osteoarthritis) (2) Studies reporting on non-English language versions of the pain measures (3) Trials of interventions for pain unless assessment of psychometric properties was noted in the abstract (4) Studies of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, orofacial pain, or headache |

Our primary outcome was whether a minimal important difference (MID) had been established for each measure, with a focus on minimal clinically important difference vs. statistically detectable difference. Secondary outcomes related to measures’ psychometric properties of responsiveness to change, validity, and retest reliability. The 17 pain measures assessed in this review were selected by pain experts in the SOTA workgroup and are outlined in more detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of Pain Measures

| Scale | Development pain type | Pain Domain | Length | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | LBP | Knee/hip | Other | Severity/intensity | Function/interference | Number of items | |

| BPI (Cleeland 1994)14 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 17 | |||

| DVPRS (Buckenmaier 2012)15 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 5 | |||

| GCPS (von Korff 1992)16 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |||

| HOOS (Klassbo 2003)17 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 40 | |||

| KOOS (Roos 2003)18 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 42 | |||

| MPQ (McCaffery 1989)19 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 78 | |||

| MPI/WHYMPI (Kerns 1985)20 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 52 | ||

| NRS (McCaffery 1989)19 | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | ||||

| ODI (Smeets 2011)21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 10 | |||

| PGIC (Farrar 2001)22 | ? | ? | ? | 1 | |||

| PEG (Krebs 2009)23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||

| PROMIS-PI (PROMIS Web site)24 | ✓ | ✓ | 41 | ||||

| RMDQ (Roland 1983)25 | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | ||||

| SF-36 BPS (Ware 1998)26 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | |||

| VAS (Wewers 1990)27 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | |||

| WOMAC (Am Coll Rheum)28 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 24 | |||

| Wong Faces Scale (Wong-Baker Web site)29 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | |||

SAQ self-administered questionnaire, ? not identified

Search Strategy

We followed a multi-pronged search strategy. First, we searched MEDLINE (Ovid) from January 2000 to January 2017 for English language publications. Our search strategy, developed with input from a medical librarian, included Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms for Pain Measurement and specific locations/types of pain (e.g., Low Back) along with title and abstract words. The search was designed to include all study designs, including systematic reviews. The full search strategy is presented in Supplemental Content Table 1. At the request of reviewers of the full evidence report, we repeated the search with MeSH and title/abstract terms for fibromyalgia. Second, we used Google Scholar, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and PubMed to identify articles not found through the MEDLINE search. Third, we searched for Web sites associated with each pain measure and hand-reviewed all Web references, including those that pre-dated 2000. We also searched for original development and validation papers associated with each measure, regardless of publication date. Fourth, we hand-reviewed the reference lists of all included studies and the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews identified through MEDLINE. Fifth, we invited the SOTA experts to identify additional key articles for review. Sixth, the draft evidence report underwent peer review (including SOTA experts), and peer reviewers were asked to identify any potentially eligible references. All identified references were assessed for eligibility. We set no date limitations on publications identified through hand reviews of reference lists, Web sites, or expert nomination.

Study Selection

Eligibility criteria are presented in Table 1. Abstracts of studies identified in our MEDLINE search were reviewed by trained staff. The full text of potentially eligible articles from abstract review, and of all articles identified from reference list searching or online sources, was reviewed independently by two researchers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data Abstraction and Quality Assessment

From each eligible study, trained staff abstracted (1) study/population characteristics: location of study, funding source, measurement scales evaluated, time period of assessment (e.g., reporting pain over past week, past month), mode of administration, setting, chronic pain condition, study inclusion/exclusion criteria, baseline pain characteristics, sample size, age, gender, and race/ethnicity, and (2) our psychometric outcomes of interest. For the primary outcome, we noted whether the minimal important difference was clinically anchored (e.g., based on the smallest difference at which participants felt better or worse) or based solely on statistical parameters (e.g., standard error of the measurement). Data were abstracted onto standardized forms piloted by research staff. All data abstraction was completed by one reviewer and verified by another. The psychometric properties represent quality measures; no further quality assessment was done.

Data Synthesis

We summarized included studies to provide an overview of the populations and pain conditions for which the psychometric properties of measures have been evaluated. We present frequency of estimation of each psychometric outcome for each measure in the form of a heat map and provide a tabular summary of primary outcome results.

RESULTS

Literature Flow

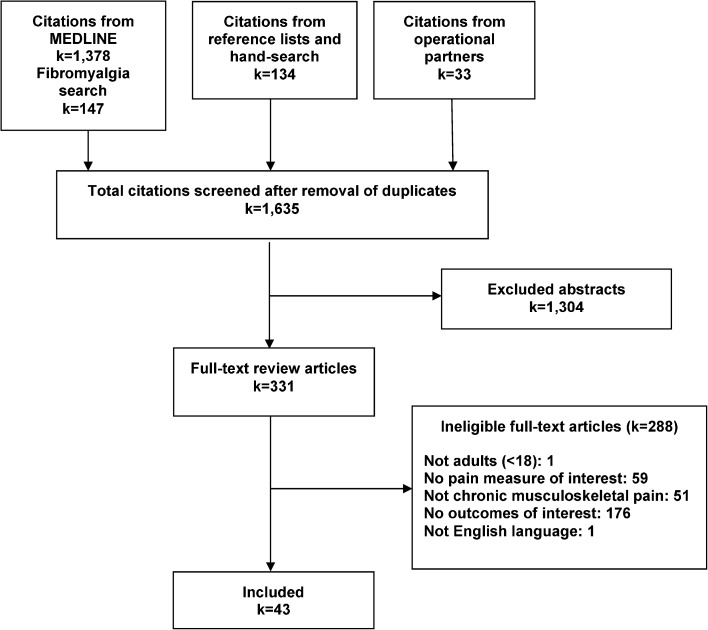

The literature flow diagram (Fig. 1) illustrates the process of study review and selection. Using our various search strategies, we identified 1635 abstracts, of which 331 proceeded to full-text review. Over half of the articles excluded after full-text review did not report the psychometric properties of interest; over one-third did not assess a pain measure of interest and/or did not study a population documented to have chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Figure 1.

Literature flow chart.

Overview of Study Characteristics

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the pain measurement studies included in the review. We included 43 studies: 23 from the USA,20,23,30,31,36,38,39,43,45,46,48–52,56,59,62,64–67,70 3 from Canada,32,57,60 one from South America,41 5 from Australia,34,35,47,54,63 and 11 from Europe.33,37,40,42,44,53,55,58,61,68,69 Of the US studies, four enrolled exclusively military Veterans20,48,52,65 and two enrolled both Veterans and non-Veterans.23,50 Study enrollments ranged from 3053 to 99864 with 29 enrolling more than 100 and 3 enrolling more than 500.36,46,64 The most common chronic musculoskeletal pain condition was low back pain (LBP), with 16 studies enrolling only LBP patients.31,33,34,36,37,40,44–46,49,52,54,55,59,66,68 Thirteen studies included patients with any chronic musculoskeletal pain.20,30,35,38,41,48,51,53,57,61,64,65,70 Mean age, reported in 40 studies, ranged from 32 years69 to 80 years45: less than 50 years in 18 studies, 50 to 59 years in 15 studies, and 60 years and older in 7 studies. The percentage of women ranged from 8 to 19% in the studies that enrolled exclusively US military Veterans. Five of the remaining studies enrolled fewer than 50% women,34,43,53,58,62 29 enrolled 50% or more, and 5 did not report the percentage of women enrolled. Race/ethnicity was reported in 18 of the studies, all but one from the USA. The percentage of white enrollees was 75% or higher for 11 of the 18 studies. Additional study characteristics are reported in Supplemental Table 2 (available online).

Table 3.

Overview of Included Studies

| Author year | Scales evaluated | Study characteristics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Pain condition | Mean age (years) | Women (%) | Race/ethnicity (%) | |||||

| White | Black | Hispanic | Other | ||||||

| Anagnostis 200430 | ODI | 230 | CDMD | 43 | 53 | 60 | 29 | 11 | 0.1 |

| Askew 201631 | PROMIS-PI | 218 | LBP | N/D | 56 | 84 | 4 | 1 | 11 |

| Burhnam 201232 | MPQ, ODI | 60 | Spine | 60 | 67 | N/D | |||

| Changulani 200933 | ODI, VAS | 107 | LBP | 58 | 58 | N/D | |||

| Chansirinukor 200534 | RMDQ | 143 | LBP | 38 | 26 | N/D | |||

| Chien 201335 | BPI | 254 | General MSP | 51 | 50 | N/D | |||

| Cook 200836 | RMDQ | 875 | LBP | 47 | N/D | 85 | 9 | 3 | Asian, 2; other, 1 |

| de Vet 200737 | NRS | 438 | LBP | N/D | N/D | N/D | |||

| Deyo 201638 | PROMIS-PI-SF | 198 | General MSP | 67 | 62 | 92 | N/D | 4 | 4 |

| Driban 201539 | PROMIS-PI, SF-36 BPS, WOMAC | 204 | Knee (OA) | 60 | 70 | 53 | 36 | N/D | 12 |

| Fisher 199740 | MPQ, ODI | 54 | LBP | 41 | 63 | N/D | |||

| Gallasch 200741 | Wong Faces, NRS, VAS | 32 | General MSP | 51 | N/D | N/D | |||

| Gentelle-Bonnassies 200042 | VAS, WOMAC | 80 | Knee (OA) | 62 | 70 | N/D | |||

| Godil 201543 | NRS | 88 | Neck and arm | 52 | 44 | N/D | |||

| Gronblad 199344 | ODQ, VAS | 94 | LBP | 43 | 51 | N/D | |||

| Hicks 200945 | ODI, SF-36 BPS | 107 | LBP | 80 | 72 | 100 | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| Jensen 201246 | VAS | 639 | LBP | 52 | 62 | 90 | 5 | N/D | Asian, 1; other, 4 |

| Kamper 201547 | NRS, SF-36 BPS | 280 | Whiplash | 44 | 65 | N/D | |||

| Kean 201648* | BPI, PEG, PROMIS-PI-SF, SF-36 BPS | 244 | MSP | 55 | 17 | 77 | 19 | N/D | 4 |

| Keller 200449 | BPI, GCPS, SF-36 BPS, RMDQ | 131 | LBP | 46 | N/D | N/D | |||

| Kerns 198520* | MPI (WHYMPI), MPQ | 120 | Chronic MSP | 51 | 19 | N/D | |||

| Krebs 201050† | BPI, GCPS, PEG, RMDQ, SF-36 BPS | 427 | Back, hip, knee | 59 | 53 | 58 | 38 | N/D | 4 |

| Krebs 200923† | BPI, GCPS, PEG, PGIC, RMDQ, SF-36 BPS | 500 | Back, hip, knee | 59 | 52 | 58 | 38 | N/D | 4 |

| Krebs 200751 | NRS | 275 | General MSP | 59 | 59 | 70 | 24 | N/D | 6 |

| Lovejoy 201252* | MPI, MPQ-2-SF, MPQ | 186 | LBP, neck, joint | 54 | 8 | 75 | N/D | N/D | 15 |

| Lund 200553 | VAS | 30 | MSP | 43 | 43 | N/D | |||

| Macedo 201154 | RMDQ | 461 | LBP | 53 | 61 | N/D | |||

| Maughan 201055 | NRS, ODI, RMDQ | 48 | LBP | 52 | 67 | N/D | |||

| Merriwether 201656 | PROMIS-PI | 106 | Fibromyalgia | 49 | 100 | 96 | N/D | N/D | 4 |

| Mikail 199357 | MPI, ODI | 315 | General MSP | 44 | 53 | N/D | |||

| Nilsdotter 200358 | HOOS, WOMAC, SF-36 BPS | 62 | Hip (OA) | 73 | 45 | N/D | |||

| Parker 201259 | ODI, VAS | 47 | LBP | 55 | 64 | N/D | |||

| Pinsker 201560 | NRS, WOMAC | 142 | Ankle | 61 | 54 | N/D | |||

| Scott 201561 | PGIC | 476 | Not specified | 46 | 67 | 72 | 17 | N/D | Asian, 7; other, 4 |

| Sindhu 201162 | NRS, VAS | 33 | Elbow, forearm, hand | 39 | 48 | N/D | |||

| Stewart 200763 | NRS, SF-36 BPS | 132 | Whiplash | 43 | 67 | N/D | |||

| Stroud 200464 | RMDQ | 998 | Not specified | 44 | 57 | 84 | 3 | 4 | Asian, 2; Native American, 4; other, 3 |

| Tan 200465* | BPI, RMDQ | 440 | Not specified | 55 | 8 | 72 | 21 | N/D | 7 |

| Tong 200666 | VAS | 52 | LBP | 41 | 62 | 88 | 3 | N/D | Asian, 3; other, 6 |

| Trudeau 201567 | WOMAC, NRS | 47 | Knee (OA) | N/D | N/D | N/D | |||

| van der Roer 200668 | NRS | 138 | LBP | 44 | 59 | N/D | |||

| van Grootel 200769 | VAS | 118 | TMD | 32 | 93 | N/D | |||

| Wittink 200470 | MPI, ODI, SF-36 BPS | 87 | Chronic pain | 47 | 67 | 79 | N/D | N/D | 21 |

CDMD chronic disabling musculoskeletal disorders, LBP low back pain, MSP musculoskeletal pain, N/D not determined, OA osteoarthritis, TMD temporomandibular disorder

*Enrolled exclusively US Veterans

†Enrolled US Veterans and non-Veterans; results not stratified by Veteran status

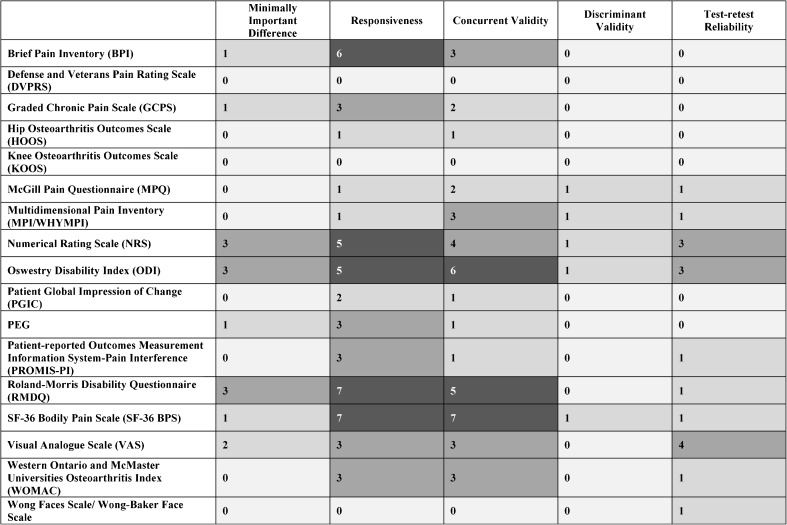

Heat Map

Figure 2 presents a heat map summarizing findings for the 17 pain measures on four psychometric outcomes of interest: MID, responsiveness, validity (concurrent and/or discriminant), and test-retest reliability. As the heat map shows, 14 measures had data reported on both responsiveness and concurrent validity, 5 measures had data reported on discriminant validity, and 10 measures had data reported on test-retest reliability. Data on all four main psychometric outcomes of interest were reported for five measures: Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), SF-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The highest numbers of relevant studies were also found on these five measures. Data on MID, responsiveness, and validity were reported for Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS), and Pain intensity, Enjoyment of life, and General activity (PEG). Data on responsiveness, validity, and test-retest reliability were reported for Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI)/West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System - Pain Interference (PROMIS-PI), and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC). We found no studies meeting eligibility criteria for the DVPRS or the KOOS. Screened studies of the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) were not specific to chronic musculoskeletal pain, and studies of the KOOS did not administer the measure and/or report findings in English. Supplemental Table 3 (in electronic appendices) identifies specific reviewed studies within this evidence map configuration, and Supplemental Table 4 contains more details on reported quantitative indicators of psychometric properties and relevant study design features.

Figure 2.

Number of studies reporting psychometric properties.

Primary Psychometric Outcome

Table 4 reports findings on the primary psychometric outcome, minimal important difference (MID). The VAS is reported twice in this table because the scoring range differed 10-fold across the two studies. Table 4 demonstrates the variety of statistical approaches used to estimate MID. Four studies calculated measure-specific minimal clinically important differences (MCIDs) using a clinically anchored approach,37,55,59,68 and one study used two different populations to calculate statistically detectable differences that were then compared to global ratings of change via kappa statistics.50 Three studies used distribution-based statistical estimations only.34,45,69

Table 4.

Summary of Results: Minimal Important Difference (MID)

| Measure | Range | Number of studies | N per study (ref) |

Minimal important difference (MID) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated using a clinical anchor | Estimated using statistical approaches | |||||||||

| ROC/optimal cutoff | 95% limit cutoff | Average change among responders | Change difference, responders vs. non-responders | Minimal detectable change | Smallest detectable difference | SEM* | ||||

| Oswestry Disability Index | 0–100 | 3 | 4759 | 4.0 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 2.0† | |||

| 6355 | 7.5 | 16.7‡ | ||||||||

| 10745 | 10.7§ | |||||||||

| Visual Analog Scale | 0–10 mm | 1 | 4759 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.0 | 2.2† | |||

| Visual Analog Scale | 0–100 mm | 1 | 11869 | 49# | ||||||

| Bodily Pain Index | 0–10 | 2 | 20550 | 0.6 | ||||||

| 22250 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| PEG | 0–10 | 2 | 20550 | 1.8 | ||||||

| 22250 | 1.9 | |||||||||

| Chronic Pain Grade-intensity | 0–100 | 2 | 20550 | 9.0 | ||||||

| 22250 | 9.9 | |||||||||

| Chronic Pain Grade-disability | 0–100 | 2 | 20550 | 8.7 | ||||||

| 22250 | 10.3 | |||||||||

| Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire | 0–24 | 4 | 6355 | 3.5 | 4.9‡ | |||||

| 20550 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 22250 | 1.2 | |||||||||

| 14334 | 7.5‡ | |||||||||

| SF-36 Bodily Pain Scale | 0–100 | 2 | 20550 | 9.8 | ||||||

| 22250 | 11.8 | |||||||||

| Numeric Rating Scale | 0–10 | 3 | 6355 | 4.0 | 2.4‡ | |||||

| 13537 | 3.5 | 4.7 | ||||||||

| 13868 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 4.5‡ | |||||||

*Standard error of measurement

†Estimated by the upper value of the 95% confidence interval for average change score seen in the cohort defined by anchor to be non-responders

‡Estimated by 1.96 × square root of 2 × SEM test-retest

§SEM determined from participants classified as stable. The SEM was then used to calculate the 90% CI and then multiplied by the square root of 2

#Estimated by the standard deviation of the difference values × 1.96

DISCUSSION

This focused evidence review evaluated published research on psychometric properties of 17 key patient-reported pain outcome measures assessed in chronic musculoskeletal pain populations. Of the five scales with reported data on all four psychometric outcomes (ODI, RMDQ, SF-36 BPS, NRS, and VAS), three (the ODI, RMDQ, and SF-36 BPS) measure multiple pain domains. The NRS and VAS varied among studies with respect to key construct (pain severity or pain-related functional impairment), phrasing, recall periods, and score ranges, making this overview more a cataloging of different numeric rating scales and visual analog scales than a review of two clearly defined pain measures. Seven additional scales (BPI, GCPS, MPI/WHYMPI, MPQ, PEG, PROMIS-PI, and WOMAC) also had evidence for three key psychometric properties. Findings are consistent with pain outcome measurement reviews focused on specific pain-related diagnoses: a review focused on responsiveness of patient-reported health outcome measures for LBP found the ODI and RMDQ to be the most comprehensively validated,71 and a previous review of back-specific functional status questionnaires for LBP found the ODI and RMDQ to have been most frequently studied, with good measurement properties in their original form as retested in multiple settings.72

The range of MID assessment methods identified in this review reflects variation in current MID-related research. Assessments of minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for a patient-reported outcome measure involve anchoring the measure to an indicator of meaningful patient-reported change in a clinical outcome.73–75 While some MID estimates reported here constitute MCIDs anchored to patient-reported clinical improvement via adaptations of the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC),37,55,59,68 others are purely estimates of statistical minimum detectable change (MDC) based on study population distribution characteristics34,45,69 without reference to clinical import of that change. Comparing anchor-based MCID findings with distribution-based MDC findings can be useful in MID estimation, as this allows researchers to consider both an external benchmark of clinical change and a measure of change detectable despite variation.37,73,74 Reviewed studies, however, contained relatively few estimates via any method. Estimation methods also differed substantially, resulting in large discrepancies both within and across measures, and precluding comparison and generalization of measure-specific MIDs. The widespread application of interpreting a 30% change from baseline as an MID—originally assessed using an NRS for pain severity22 and ultimately recommended for a range of patient-reported pain outcome measures—78 may have discouraged measure-specific MID development. Further research should explore whether this approach is empirically generalizable. Consensus is needed on optimal approaches to developing and reporting MID for patient-reported measures in chronic musculoskeletal pain.

There is no gold standard comparator for assessment of pain measure validity in the domains assessed. Included studies’ methods of assessing concurrent/criterion validity involved finding correlations between a measure of interest and another measure or subscale of interest. Other assessments arguably relevant to construct validity, such as relationships of self-reported pain-related functioning measures to objective physical performance measures, were less commonly identified, consistent with the state of current physical function research in pain.8 Perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore, our review identified a self-referential network of patient-reported outcome measures validated against one another, making validity estimates difficult to compare within or across measures. Future research could further investigate the network of validity comparisons to clarify underlying assumptions and identify gaps requiring conceptual research. Responsiveness findings in reviewed studies were also challenging to compare both within and across measures. Some methods of comparing pain measure changes within clinical trials of pain interventions cannot separate an intervention’s estimated effectiveness (either true differences or chance findings of difference) from the responsiveness of the pain measure used to assess it. Few methods recognize the inherent challenge that short-term fluctuations in pain, which commonly occur in chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions, pose to the capacity of pre-post assessments to track pain trajectory over time. Interpreting test-retest reliability estimates has similar conceptual challenges: separating undesirable measurement variability from variability that reflects actual fluctuations in pain can be difficult. Thus, short-term fluctuations in a measure may not indicate a lack of test/retest reliability, and may instead be evidence of true responsiveness. Researchers interested in comparing measures’ responsiveness and test-retest reliability should consider available psychometric evidence in the context of their own work, including the recall period of interest, the expected amount and time frame of change in the pain domains they plan to assess, and their desired study design (e.g., pre-post assessment vs. longitudinal repeated-measures assessment).

Chronic musculoskeletal pain definition and reporting varied widely across reviewed studies. The required duration for pain to be considered “chronic” was inconsistent and was not always reported. Pain type (e.g., musculoskeletal), primary diagnostic cause (e.g., osteoarthritis), and primary bodily site(s) (e.g., low back) were inconsistently reported, as were relevant characteristics such as pain duration and levels at baseline, treatment use, and co-existing physical or mental health conditions. Such differences reflect active discussion in current pain research: when and how duration, causal diagnoses, and bodily site affect key pain qualities, and when and how intermittent pain differs meaningfully from chronic continuous pain.11,79 Research is needed to define target populations and reporting standards for pain-relevant characteristics in psychometric research on chronic musculoskeletal pain.

The majority of studies were conducted in populations with over 50% women and mean ages 40–59. Most studies did not report race or ethnicity; of those that did, all included more than 50% white participants, and most included more than 75% white participants. No studies reported outcomes stratified by sex or gender, age range, or race/ethnicity. Generalizability of psychometric findings is thus limited by both demographic underreporting and population homogeneity. Given substantial evidence of the influence of age and psychosocial factors on individuals’ experiences and reporting of both pain-related functional impairment and pain severity,76,77,80,81 there is a need for consensus on key study population demographic and clinical characteristics, more consistent reporting of these population characteristics within studies, and further research on how measures’ psychometric properties generalize or change across age ranges and psychosocial categories.

Our review was limited to studies that published results in English. We also excluded studies that evaluated non-English language versions of eligible scales. This decision was supported by evidence on the limited generalizability of self-report measures’ psychometric properties across languages and highlights the need for linguistic and cultural validation of pain measures.80,82 With respect to search strategy, our primary abstract search was limited to 2000 onward. We complemented this, however, by applying no date limits to hand-searches of included studies’ reference lists, other reviews, and expert/peer reviewer suggestions. Finally, our criteria may have excluded some studies of psychometric properties of measures developed and validated prior to the popularization of specifying chronicity and duration of pain. Researchers considering such pain measures will need to consider the relevance of past psychometric work in the context of current conceptual pain research, and of their planned studies’ objectives and target populations.

This focused evidence review had key elements of an evidence mapping approach: systematically surveying the psychometric literature on expert-identified pain measures, summarizing quantities of studies on key psychometric outcomes, and identifying research gaps and relevant challenges to data synthesis.83 We developed this approach to illuminate the research gaps and data synthesis challenges that became evident through systematic review. Ultimately, we found that primary psychometric research on these measures within chronic musculoskeletal pain populations was limited, with the most evidence on reviewed psychometric properties found for the ODI, RMDQ, SF-36 BPS, NRS, and VAS. Key challenges in current musculoskeletal pain measurement research include substantial variation in methods of estimating psychometric properties, defining chronic musculoskeletal pain, and reporting patient demographics. Findings indicate that further methods research is needed to validate patient-reported pain outcome measures in populations with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 90 kb)

Funders

This work is based on a review supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Prior Presentations

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morgan D, Lipton R. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA. 2003;290:2443–2454. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.18.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butchart A, Kerr EA, Heisler M, Piette JD, Krein SL. Experience and management of chronic pain among patients with other complex chronic conditions. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(4):293–298. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31818bf574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gereau RW, Sluka KA, Maixner W, et al. A pain research agenda for the 21st century. J Pain. 2014;15(12):1203–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, et al. Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2006;125(3):208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2009;146(3):238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, McDermott MP, et al. Analyzing multiple endpoints in clinical trials of pain treatments: IMMPACT recommendations. Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials. Pain. 2008;139(3):485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor AM, Phillips K, Patel KV, et al. Assessment of physical function and participation in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT/OMERACT recommendations. Pain. 2016;157(9):1836–1850. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Dworkin SF, Amtmann D, et al. Report of the NIH Task Force on Research Standards for Chronic Low Back Pain. J Pain. 2014;15(6):569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Revicki D, et al. Identifying important outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: an IMMPACT survey of people with pain. Pain. 2008;137(2):276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younger J, McCue R, Mackey S. Pain outcomes: a brief review of instruments and techniques. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(1):39–43. doi: 10.1007/s11916-009-0009-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldsmith ES, Murdoch M, Taylor B, et al. Rapid evidence review: measures for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; VA Evidence-based Synthesis Program Reports. 2017; http://vaww.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/chronicpain-measures.cfm. Accessed 11/9/2017. [PubMed]

- 14.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckenmaier CC, 3rd, Galloway KT, Polomano RC, McDuffie M, Kwon N, Gallagher RM. Preliminary validation of the Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) in a military population. Pain Med. 2013;14(1):110–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–149. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klassbo M, Larsson E, Mannevik E. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score: an extension of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index. Scand J Rheumatol. 2003;32:46–51. doi: 10.1080/03009740310000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roos EM, Lohmander LS. The Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS): from joint injury to osteoarthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCaffery M, Beebe A. Pain: Clinical Manural for Nursing Practices. St. Louis, MO; 1989.

- 20.Kerns RD, Turk DC, Rudy TE. The West Haven-Yale Multidimensional Pain Inventory (WHYMPI) Pain. 1985;23(4):345–356. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smeets R, Koke A, Lin CW, Ferreira M, Demoulin C. Measures of function in low back pain/disorders: Low Back Pain Rating Scale (LBPRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Progressive Isoinertial Lifting Evaluation (PILE), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(Suppl 11):S158–173. doi: 10.1002/acr.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733–738. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pain interference: a brief guide to the PROMIS pain interference instruments. 2015; https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS%20Pain%20Interference%20Scoring%20Manual.pdf. Accessed 11/8/2017.

- 25.Roland MO. The natural history of back pain. Practitioner. 1983;227(1381):1119–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):903–912. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00081-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health. 1990;13(4):227–236. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Rheumatology. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC). 2017; http://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Rheumatologist/Research/Clinician-Researchers/Western-Ontario-McMaster-Universities-Osteoarthritis-Index-WOMAC. Accessed 11/8/2017.

- 29.Wong-Baker FACES® history. 2016. http://wongbakerfaces.org/us/wong-baker-faces-history/. Accessed 11/8/2017.

- 30.Anagnostis C, Gatchel RJ, Mayer TG. The pain disability questionnaire: a new psychometrically sound measure for chronic musculoskeletal disorders. Spine. 2004;29(20):2290–2302. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000142221.88111.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Askew RL, Cook KF, Revicki D, Cella D, Amtmann D. Evidence from diverse clinical populations supported clinical validity of PROMIS pain interference and pain behavior. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burnham R, Stanford G, Gray L. An assessment of a short composite questionnaire designed for use in an interventional spine pain management setting. PM R. 2012;4(6):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Changulani M, Shaju A. Evaluation of responsiveness of Oswestry low back pain disability index. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(5):691–694. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chansirinukor W, Maher CG, Latimer J, Hush J. Comparison of the functional rating index and the 18-item Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire: responsiveness and reliability. Spine. 2005;30(1):141–145. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200501010-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chien CW, Bagraith KS, Khan A, Deen M, Strong J. Comparative responsiveness of verbal and numerical rating scales to measure pain intensity in patients with chronic pain. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1653–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook KF, Choi SW, Crane PK, Deyo RA, Johnson KL, Amtmann D. Letting the CAT out of the bag: comparing computer adaptive tests and an 11-item short form of the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire. Spine. 2008;33(12):1378–1383. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181732acb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Vet HC, Ostelo RW, Terwee CB, et al. Minimally important change determined by a visual method integrating an anchor-based and a distribution-based approach. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(1):131–142. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9109-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deyo RA, Katrina R, Buckley DI, et al. Performance of a Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Short Form in older adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain Med. 2016;17(2):314–324. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Driban JB, Morgan N, Price LL, Cook KF, Wang C. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) instruments among individuals with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of floor/ceiling effects and construct validity. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Fisher K, Johnston M. Validation of the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, its sensitivity as a measure of change following treatment and its relationship with other aspects of the chronic pain experience. Physiother Theory Pract. 1997;13:67–80. doi: 10.3109/09593989709036449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallasch CH, Alexandre NM. The measurement of musculoskeletal pain intensity: a comparison of four methods. Rev Gaucha Enferm. 2007;28(2):260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gentelle-Bonnassies S, Le Claire P, Mezieres M, Ayral X, Dougados M. Comparison of the responsiveness of symptomatic outcome measures in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13(5):280–285. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)13:5<280::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Godil SS, Parker SL, Zuckerman SL, Mendenhall SK, McGirt MJ. Accurately measuring the quality and effectiveness of cervical spine surgery in registry efforts: determining the most valid and responsive instruments. Spine J. 2015;15(6):1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.07.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gronblad M, Hupli M, Wennerstrand P, et al. Intercorrelation and test-retest reliability of the Pain Disability Index (PDI) and the Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (ODQ) and their correlation with pain intensity in low back pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:189–195. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hicks GE, Manal TJ. Psychometric properties of commonly used low back disability questionnaires: are they useful for older adults with low back pain? Pain Med. 2009;10(1):85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jensen MP, Schnitzer TJ, Wang H, Smugar SS, Peloso PM, Gammaitoni A. Sensitivity of single-domain versus multiple-domain outcome measures to identify responders in chronic low-back pain: pooled analysis of 2 placebo-controlled trials of etoricoxib. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(1):1–7. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182236209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamper SJ, Grootjans SJ, Michaleff ZA, Maher CG, McAuley JH, Sterling M. Measuring pain intensity in patients with neck pain: does it matter how you do it? Pain Pract. 2015;15(2):159–167. doi: 10.1111/papr.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kean J, Monahan PO, Kroenke K, et al. Comparative responsiveness of the PROMIS Pain Interference Short Forms, Brief Pain Inventory, PEG, and SF-36 Bodily Pain Subscale. Med Care. 2016;54(4):414–421. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the Brief Pain Inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krebs EE, Bair MJ, Damush TM, Tu W, Wu J, Kroenke K. Comparative responsiveness of pain outcome measures among primary care patients with musculoskeletal pain. Med Care. 2010;48(11):1007–1014. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krebs EE, Carey TS, Weinberger M. Accuracy of the pain numeric rating scale as a screening test in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(10):1453–1458. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lovejoy TI, Turk DC, Morasco BJ. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the revised short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. J Pain. 2012;13(12):1250–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lund I, Lundeberg T, Sandberg L, Budh CN, Kowalski J, Svensson E. Lack of interchangeability between visual analogue and verbal rating pain scales: a cross sectional description of pain etiology groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Macedo LG, Maher CG, Latimer J, Hancock MJ, Machado LA, McAuley JH. Responsiveness of the 24-, 18- and 11-item versions of the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(3):458–463. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maughan EF, Lewis JS. Outcome measures in chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1484–1494. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1353-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merriwether EN, Rakel BA, Zimmerman MB, et al. Reliability and construct validity of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) instruments in women with fibromyalgia. Pain Med. 2016. 10.1093/pm/pnw187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Mikail SF, DuBreuil S, D'eon JL. A comparative analysis of measures used in the assessment of chronic pain patients. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(1):117–120. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.5.1.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nilsdotter AK, Lohmander LS, Klassbo M, Roos EM. Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS)—validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parker SL, McGirt MJ. Determination of the minimum improvement in pain, disability, and health state associated with cost-effectiveness: introduction of the concept of minimum cost-effective difference. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(6):1149–1155. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318271ebde. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pinsker E, Inrig T, Daniels TR, Warmington K, Beaton DE. Reliability and validity of 6 measures of pain, function, and disability for ankle arthroplasty and arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(6):617–625. doi: 10.1177/1071100714566624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott W, McCracken LM. Patients’ impression of change following treatment for chronic pain: global, specific, a single dimension, or many? J Pain. 2015;16(6):518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sindhu BS, Shechtman O, Tuckey L. Validity, reliability, and responsiveness of a digital version of the visual analog scale. J Hand Ther. 2011;24(4):356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart M, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Bogduk N, Nicholas M. Responsiveness of pain and disability measures for chronic whiplash. Spine. 2007;32(5):580–585. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000256380.71056.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroud MW, McKnight PE, Jensen MP. Assessment of self-reported physical activity in patients with chronic pain: development of an abbreviated Roland-Morris disability scale. J Pain. 2004;5(5):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, Shanti BF. Validation of the Brief Pain Inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain. 2004;5(2):133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tong HC, Geisser ME, Ignaczak AP. Ability of early response to predict discharge outcomes with physical therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain Pract. 2006;6(3):166–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2006.00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trudeau J, Van Inwegen R, Eaton T, et al. Assessment of pain and activity using an electronic pain diary and actigraphy device in a randomized, placebo-controlled crossover trial of celecoxib in osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract. 2015;15(3):247–255. doi: 10.1111/papr.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van der Roer N, Ostelo RW, Bekkering GE, van Tulder MW, de Vet HC. Minimal clinically important change for pain intensity, functional status, and general health status in patients with nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 2006;31(5):578–582. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000201293.57439.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Grootel RJ, van der Bilt A, van der Glas HW. Long-term reliable change of pain scores in individual myogenous TMD patients. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(6):635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wittink H, Turk DC, Carr DB, Sukiennik A, Rogers W. Comparison of the redundancy, reliability, and responsiveness to change among SF-36, Oswestry Disability Index, and Multidimensional Pain Inventory. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(3):133–142. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200405000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cleland J, Gillani R, Bienen EJ, Sadosky A. Assessing dimensionality and responsiveness of outcomes measures for patients with low back pain. Pain Pract. 2011;11(1):57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grotle M, Brox J, Vollestad N. Functional Status and Disability Questionnaires: what do they assess?: A systematic review of Back-Specific Outcome Questionnaires. Spine. 2005;30(1):130–140. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000149184.16509.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(2):102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crosby RD, Kolotkin RL, Williams GR. Defining clinically meaningful change in health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(5):395–407. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turner D, Schunemann HJ, Griffith LE, et al. The minimal detectable change cannot reliably replace the minimal important difference. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. Gender differences in the reporting of physical and somatoform symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(2):150–155. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199803000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10(5):447–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Von Korff M. Assessment of chronic pain in epidemiological and health services research. New York: Guilford Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Booker SS, Herr K. The state-of-“cultural validity” of self-report pain assessment tools in diverse older adults. Pain Med. 2014;16(2):232–239. doi: 10.1111/pme.12496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Racial/ethnic disparities in the assessment and treatment of pain: psychosocial perspectives. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):131–141. doi: 10.1037/a0035204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5:28. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 90 kb)