Abstract

Total body irradiation (TBI) has been included in standard conditioning for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) before hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Non-TBI regimens have incorporated busulfan (BU) to decrease toxicity. This retrospective study analyzed TBI and BU on outcomes of ALL patients aged 18-60 years, in first or second complete remission (CR), undergoing HLA-compatible sibling, related or unrelated donor HCT, reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research from 2005 to 2014. TBI plus etoposide (25%) or cyclophosphamide (75%) was used in 819 patients, and intravenous BU plus fludarabine (41%), clofarabine (30%), cyclophosphamide (15%) or melphalan (13%) was used in 299. BU-containing regimens were analyzed together, since no significant differences for patient outcomes were noted between them. BU patients were older, with better performance status, took longer to achieve CR1 and receive HCT, were treated more recently, and were more likely to receive peripheral blood grafts, anti-thymocyte globulin, and/or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. With median follow-up of 3.6 years for BU and 5.3 years for TBI, adjusted 3-year outcomes showed treatment-related mortality BU 19% vs. TBI 25% (p=.04); relapse BU 37% vs. TBI 28% (p=.007); disease-free survival (DFS) Bu 45% vs. TBI 48% (p=.35); and overall survival (OS) BU 57% vs. TBI 53% (p=.35). In multivariate analysis, BU patients had higher risk of relapse (RR 1.46, 95% C.I.1.15-1.85, p=.002) compared with TBI patients. Despite the higher relapse, BU-containing conditioning led to similar OS and DFS following HCT for ALL.

Keywords: Allogeneic transplant, Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Total body irradiation, Busulfan

INTRODUCTION

Total body irradiation (TBI)-based conditioning regimens are considered standard for patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), with expected survival rates of 50% to 60% in first complete remission (CR1)(1, 2). However, myeloablative doses of TBI are associated with considerable acute and long-term toxicity, treatment-related mortality (TRM) rates of 20%-45% following HCT, and increased risk of secondary malignancy (2–4). In efforts to minimize toxicity, the combination of oral busulfan (BU) and cyclophosphamide (Cy) was developed for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and later tested in ALL. Retrospective (5) and prospective studies (6) in children with ALL compared Cy-TBI with oral, typically non-targeted BU and Cy and found that relapse rates were not statistically different between the two groups, but TRM was increased with BU-Cy because of more veno-occlusive disease (VOD) and interstitial pneumonitis, and thus, survival was better with Cy-TBI.

Since these reports, the intravenous (i.v.) formulation of BU has been developed because of its more predictable pharmacokinetics, and it is increasingly used. Study results across different disease types show a better safety profile than the oral formulation (7, 8). Furthermore, pharmacokinetic (PK)-directed dosing of i.v. BU affords even greater safety (9–11) and efficacy (12). A recent Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) multicenter cohort analysis in adult patients with AML receiving HCT following Cy-TBI or myeloablative, i.v. BU-based conditioning regimens found superior survival for the BU-based group (56% vs. 48%, p=.02)(13). Furthermore, Bartelink and colleagues recently reported on transplant outcomes for children undergoing HCT following i.v. BU-based conditioning. (14) Patients with optimized BU exposure had less risk for relapse and better event-free survival compared to those with very low or very high BU exposure, underscoring the importance of PK-directed, i.v. BU administration for improved clinical outcomes(14). Several phase II studies in adults have reported excellent transplant outcomes with i.v. BU combined with fludarabine (Flu)(15, 16) or clofarabine (Clo)(17) in patients receiving HCT for ALL. An updated analysis of MD Anderson data with BU-Clo transplant conditioning for ALL patients in CR1 (n=62) or CR2 (n=28) revealed 2-year overall survival (OS) rates of 70% and 57%, respectively (18). Thus, we compared the outcomes of adult patients with ALL who received allogeneic HCT after treatment with myeloablative TBI-based conditioning versus i.v. BU-based regimens reported to the CIBMTR.

METHODS

Data source

The CIBMTR is a working group of an estimated 504 transplant centers worldwide that collects detailed information on transplantation and outcomes. Data were collected at the Medical College of Wisconsin or through the National Marrow Donor Program. All patients whose data were included in this study provided institutional review board-approved consent to participate in the CIBMTR Research Database and have their data included in observational research studies. Data was collected from CIBMTR forms from 2005-2014. All of the TBI-based cases (n=819) and a minority of the BU-based cases (n=67) were selected from the CIBMTR database. The remaining BU-based cases (n=232) were from MD Anderson Cancer Center or the Moffitt Cancer Center, and 218 of these cases were identified in the CIBMTR TED database.

Patient selection

Adult patients, aged 18-60 years, with B- and T-lineage ALL undergoing a first bone marrow or peripheral blood allogeneic HLA-identical sibling or well matched unrelated donor (URD) HCT in first (CR1) or second (CR2) complete remission with myeloablative TBI- or BU- based conditioning were selected. Well-matched URD had no known mismatch at HLA-A, B, C, and DRB1, using criteria recommended by CIBMTR (19). Umbilical cord blood donors, mismatched related donors, and ex vivo T-cell-depleted grafts were excluded. Preparative regimens were defined as myeloablative based on published consensus definitions (20). In patients receiving PK-guided BU, the dose was targeted to a daily area under the curve (AUC) of 4000-6000 umol/min which was considered myeloablative, and combined with either Flu, Clo, melphalan (Mel), or Cy. In the TBI group, the two most commonly used regimens of Cy-TBI or TBI plus etoposide were selected for the study.

Study objectives and definitions

The primary objective of this retrospective cohort, registry analysis was to test for equivalence in OS between patients treated with myelo-ablative TBI or BU-based conditioning regimens. Survival after HCT was defined as time from transplantation to death. Surviving patients were censored at time of last contact. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as time from transplant to treatment failure (death or relapse). Relapse was morphologically defined as >5% leukemic blasts as reported by the centers to the CIBMTR, and treatment related mortality (TRM) was considered a competing event. Treatment-related mortality was defined as death in remission, and relapse was considered a competing event. Acute graft-vs-host disease (aGVHD) was graded according to Consensus criteria (21) and chronic (c) GVHD was diagnosed by standard criteria (22). For cumulative incidence of GVHD, death without GVHD was considered a competing event.

Secondary objectives were to compare relapse, DFS, TRM, grades II–IV aGVHD, and cGVHD. Probability of DFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Values for other end points were calculated using cumulative incidence curves to accommodate competing risks. Additionally, we sought to evaluate the influence of the conditioning regimen (TBI versus i.v. BU) on post HCT outcomes among ALL risk subgroups (standard versus high) classified based on age, initial WBC and cytogenetics at diagnosis, as well as the effect of remission status (CR1 versus CR2). Cytogenetic risk was defined by CIBMTR criteria, adapted from Moorman et al(23), defining complex karyotype (≥3 chromosomal abnormalities), t(9;22), t(4;11), and hypodiploid (<46 chromosomes) as poor risk.

Statistical considerations

Patient-, disease-, and transplant-related variables for donor types were compared using chi- square statistics for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Probabilities for relapse, NRM and GVHD were calculated using the cumulative incidence (CI) estimator to accommodate competing risks. Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to calculate the probability of LFS and OS. Multivariate analysis (MVA) was performed using Cox proportional hazard model for OS, DFS, TRM, relapse, aGVHD and cGVHD. The variables considered in the multivariate models were BU vs. TBI (in all models), age, time to achieve CR1, donor type, donor/recipient sex match, graft type, cytogenetic risk, and disease status at time of HCT in addition to others suggestively important in univariate analysis. In-vivo T cell depletion was evaluated as a factor but it did not show significance in the model building process. Adjusted probabilities of LFS and survival, and adjusted cumulative incidence functions of NRM, relapse and acute and chronic GVHD were calculated using the multivariate models, stratified on type of conditioning and weighted by the pooled sample proportion value for each prognostic factor(24, 25). The assumption of proportional hazards for each factor in the Cox model was tested using time-dependent covariates. When the test indicated differential effects over time (non-proportional hazards), models were constructed breaking the post-transplant time course into two periods, using the maximized partial likelihood method to find the most appropriate breakpoint. A backward stepwise model selection approach was used to identify all significant risk factors. Factors which were significant at a 5% level were kept in the final model. Based on the available sample size, with 2 sided test at 5% significance level, we had an 80% power to detect ≥ 9% difference in 2-year and 3-year OS probability between the TBI and BU groups.

RESULTS

Patient and treatment characteristics

Patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics of the 819 patients treated with TBI-based and 299 patients treated with BU-based HCT conditioning regimens are described in Table 1. Both groups were similar with the proportions of B-lineage (83% vs. 83%), CR1 (74% vs. 75%), presence of extramedullary disease at diagnosis (14% vs. 13%), and HLA-identical sibling donors (50% vs. 56%). However, the BU group included more patients of 50-60 years of age compared to the TBI group (24% vs. 17%, p=.004), fewer patients who achieved CR1 within 8 weeks (44% vs. 55%, p=.003), fewer patients who reached transplant within 6 months of achieving CR (80% vs. 88%, p=.002), and more Ph+ patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) before and after HCT (73% vs. 50%, p <.001). Finally, more BU patients received peripheral blood grafts (84% vs. 76%, p=.005), in vivo lymphodepletion with ATG or alemtuzumab (23% vs. 12%, p <.001), tacrolimus-based GVHD prophylaxis (89% vs. 72%, p <.001), and were transplanted in the recent period, 2011 to 2015 (47% vs. 30%, p<.001), compared to TBI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Variable | TBI-based | Bu-based | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 819 | 299 | |

| Patient age | 0.004 | ||

| 18-49 | 683 (83) | 226 (76) | |

| 50-60 | 136 (17) | 73 (24) | |

| Median (range) | 37 (18-60) | 38 (18-60) | 0.04 |

| Male gender | 485 (59) | 172 (58) | 0.61 |

| KPS≥90% | 552 (67) | 216 (72) | 0.015 |

| B lineage | 677 (83) | 247 (83) | 0.11 |

| TKI pre-HCT (for Ph+) | 150 (50) | 86 (73) | <0.001 |

| White blood count at diagnosis | 0.86 | ||

| <= 30 | 443 (54) | 157 (53) | |

| 31 - 100 | 111 (14) | 39 (13) | |

| > 100 | 105 (13) | 44 (15) | |

| Missing | 160 (20) | 59 (20) | |

| Extra-medullary disease present at diagnosis | 111 (14) | 40 (13) | 0.98 |

| Cytogenetics groupinga at diagnosis | 0.03 | ||

| Poor, Ph+ | 300 (37) | 118 (39) | |

| Poor, Ph− | 121 (15) | 44 (15) | |

| Other | 314 (38) | 123 (41) | |

| Missing | 84 (10) | 14 (5) | |

| CR1 prior to HCT | 610 (74) | 223 (75) | 0.97 |

| Time to achieve CR1 | 0.003 | ||

| <=8 weeks | 449 (62) | 133 (56) | |

| >8 weeks | 309 (38) | 133 (44) | |

| Time from CR1 to HCT (for CR1) | 0.002 | ||

| 0-6 months | 749 (88) | 259 (80) | |

| >6 months | 70 (12) | 40 (20) | |

| Conditioning regimen | |||

| TBI+VP16 | 204 (25) | 0 | |

| TBI+Cy | 615 (75) | 0 | |

| Bu+Flu | 0 | 124 (41) | |

| Bu+Clo | 0 | 91 (30) | |

| Bu+Mel | 0 | 38 (13) | |

| Bu+Cy | 0 | 46 (15) | |

| Pharmacokinetics for Bu dosing | N/A | 240 (80) | |

| Dose of TBI ≥13Gy fractionated | 305 (37) | N/A | |

| CNS radiation boost administered | 67 (8) | N/A | |

| Testicular radiation boost administered | 72 (9) | N/A | |

| HLA-identical sibling donor | 408 (50) | 166 (56) | 0.09 |

| Peripheral blood graft | 623 (76) | 251 (84) | 0.005 |

| GVHD prophylaxis | <0.001 | ||

| Tacrolimus-based | 593 (72) | 267 (89) | |

| Cyclosporine-based | 207 (25) | 23 (8) | |

| Others | 4 (1) | 6 (2) | |

| Missing | 15 (2) | 3 (1) | |

| ATG/alemtuzumab given | 108 (12) | 69 (23) | <0.001 |

| Post-HCT preemptive TKI (for Ph+) | 86 (33) | 59 (55) | <0.001 |

| Year of HCT | <0.001 | ||

| 2005-2010 | 573 (70) | 158 (53) | |

| 2011-2015 | 246 (30) | 141 (47) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 63 (3-125) | 43 (3-98) |

Poor cytogenetics: complex (>= 3 abnormalities), t(9;22), t(4;11), hypodiploid (<46).

Abbreviations: TBI, total body irradiation; BU, busulfan; KPS, Karnofsky performance status; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; Ph, Philadelphia chromosome; CR, complete remission; VP16, etoposide; Cy, cyclophosphamide; Flu, fludarabine; Clo, clofarabine; Mel, melphalan; Gy, gray; CNS, central nervous system; HLA, hematopoietic cell transplantation; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; ATG, anti-thymocyte globulin; N/A, not applicable

Patients in the TBI group received fractionated TBI at 9-12 Gy (63%) or 13-16 Gy (37%) combined with Cy (75%) or etoposide (25%). The median Cy dose was 106 mg/kg (interquartile range 89.5 mg/kg-119.5 mg/kg) and the median etoposide dose was 54 mg/kg (interquartile range 47mg/kg-59 mg/kg). BU dosing was PK-directed in 80% of patients, targeting a median daily AUC 5000 umol/min (range 4000-6000). The median BU dose was 11.5 mg/kg (interquartile range 9.8-12.8 mg/kg) combined with Clo (31%), Flu (41%), Cy (15%) or Mel (13%). The Clo dose was 40 mg/m2 daily for four days. The median Flu dose was 160 mg/m2 (interquartile range 159 mg/m2-160 mg/m2). The median Mel dose was 140 mg/m2 (interquartile range 129 mg/m2-140 mg/m2).

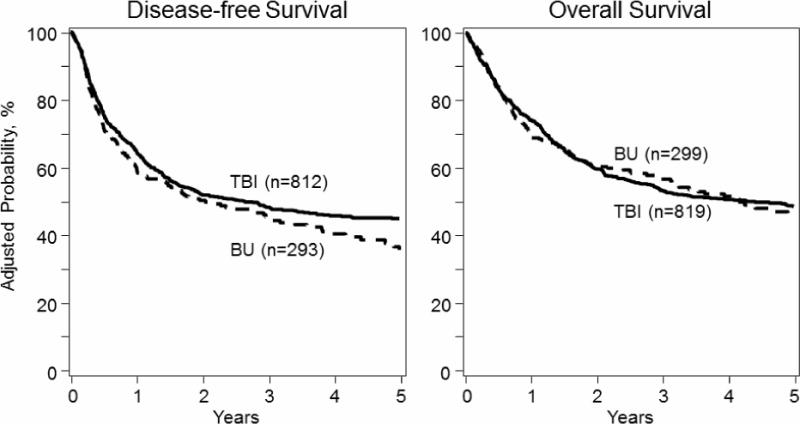

Survival and Disease-Free Survival

With a median follow-up among survivors of 43 months (range 3-98 months) in the BU-based group, and 63 months (range 3-125 months) in the TBI-based group, the overall survival was similar (57% BU vs. 53% TBI at 3 years, p=0.35, Table 3, Figure 1). Factors significantly associated with worse OS in multivariate analysis were older age ≥ 35 years [Relative Risk (RR) 1.36, 95% CI: 1.13-1.64, p=.001], HCT in CR2 (RR 1.85, 95% CI: 1.49-2.30, p<.0001), and greater than 8 weeks to achieve CR1 (RR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.09-1.58 p=.005). Absence of poor risk cytogenetic features was associated with better OS compared with Ph+ karyotype (RR 0.77, 95% CI: 0.62-0.95, p=.015). However, the presence of the Philadelphia translocation had no significant impact on survival within the poor risk cytogenetic risk group (Table 2). Disease-free survival was also similar between the two groups in univariate (45% BU vs. 48% TBI at 3 years, p=0.35, Table 3, Figure 1) and multivariate analysis (Table 2). The same factors associated with OS were also significant for DFS in multivariate analysis (Table 2). The use of PK-directed BU dosing was associated with significantly better OS compared to BU with no PK guidance. No PK guidance was associated with a 1.82 RR, 95% CI: 1.17-2.82, of higher mortality, p=.008. Due to the small sample size of patients without PK-guidance (n=46), this apparent association was not tested in multivariate analysis.

Table 3.

Adjusted probabilities of outcomes after HCT

|

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N at risk | TBI Prob (95% CI) |

N at risk | BU Prob (95% CI) |

p-value* | |

| aGVHD, grades II-IV | |||||

| day 100 | 431 | 40 (37-43)% | 140 | 47 (42-53)% | 0.025 |

| cGVHD | |||||

| 1 yr | 212 | 47 (43-50)% | 79 | 41 (36-47)% | 0.10 |

| 3 yr | 87 | 55 (52-59)% | 25 | 49 (43-55)% | 0.073 |

| TRM | |||||

| 1 yr | 470 | 16 (14-19)% | 149 | 16 (12-20)% | 0.89 |

| 3 yr | 282 | 25 (22-28)% | 76 | 19 (14-23)% | 0.039 |

| 5 yr | 198 | 27 (24-31)% | 32 | 22 (17-27)% | 0.11 |

| Relapse | |||||

| 1 yr | 470 | 19 (17-22)% | 149 | 25 (20-30)% | 0.064 |

| 3 yr | 282 | 28 (25-31)% | 76 | 37 (31-43)% | 0.0074 |

| 5 yr | 198 | 29 (26-32)% | 32 | 42 (35-48)% | 0.00050 |

| DFS | |||||

| 1 yr | 470 | 65 (61-68)% | 149 | 60 (54-65)% | 0.14 |

| 3 yr | 282 | 48 (45-52)% | 76 | 45 (39-51)% | 0.35 |

| 5 yr | 198 | 45 (41-49)% | 32 | 37 (30-43)% | 0.035 |

| OS | |||||

| 1 yr | 541 | 74 (71-77)% | 177 | 69 (64-74)% | 0.11 |

| 3 yr | 316 | 53 (50-57)% | 98 | 57 (50-62)% | 0.35 |

| 5 yr | 222 | 49 (45-52)% | 39 | 46 (39-53)% | 0.51 |

Adjusted point-wise estimates

Abbreviations: TBI, total body irradiation; BU, busulfan; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; TRM, treatment related mortality; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; N, number; Prob, probability; CI, confidence interval; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation

Figure 1. Adjusted probability of disease-free and overall-survival in adult ALL patients by conditioning regimen.

3-year DFS and OS were 48% vs. 45%, p=0.35 and 53% vs. 57%, p=0.35 for TBI vs. BU groups, respectively. Conditioning was not significantly associated with either DFS or OS in multivariate analysis.

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; TBI, total body irradiation; Bu, busulfan; N, number; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of outcomes after HCT

| Study endpoints | N | RR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall survival | |||

| Main variable: | |||

| Conditioning | |||

| TBI | 819 | 1 | |

| Bu | 299 | 1.01 (0.83-1.23) | 0.93 |

| Significant covariates: | |||

| Recipient age (years) at HCT | |||

| 18-34 | 500 | 1 | |

| 35-60 | 618 | 1.36 (1.13-1.64) | 0.001 |

| Disease status at HCT | |||

| CR1 | 833 | 1 | |

| CR2 | 285 | 1.85 (1.49-2.30) | <.0001 |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Poor, Ph+ | 418 | 1 | 0.036 |

| Poor, Ph− | 156 | 0.88 (0.66-1.16) | 0.35 |

| Other (including normal) | 446 | 0.77 (0.62-0.95) | 0.015 |

| Missing | 98 | 0.65 (0.46-0.92) | 0.016 |

| Time to achieve CR1 | |||

| ≤8 weeks | 582 | 1 | 0.013 |

| >8 weeks | 442 | 1.31 (1.09-1.58) | 0.0046 |

| Missing | 94 | 1.29 (0.93-1.78) | 0.12 |

| Disease-free survival | |||

| Main variable: | |||

| Conditioning | |||

| TBI | 812 | 1 | |

| Bu | 293 | 1.16 (0.96-1.39) | 0.13 |

| Significant covariates: | |||

| Disease status at HCT | |||

| CR1 | 825 | 1 | |

| CR2 | 280 | 1.75 (1.43-2.15) | <.0001 |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Poor, Ph+ | 415 | 1 | 0.0046 |

| Poor, Ph− | 155 | 0.86 (0.66-1.11) | 0.25 |

| Other (including normal) | 438 | 0.70 (0.57-0.85) | 0.00040 |

| Missing | 97 | 0.72 (0.52-1.00) | 0.047 |

| Time to achieve CR1 | |||

| ≤8 weeks | 574 | 1 | 0.0081 |

| >8 weeks | 437 | 1.32 (1.11-1.57) | 0.0020 |

| Missing | 94 | 1.18 (0.87-1.61) | 0.28 |

| Treatment-related mortality | |||

| Main Variable: | |||

| Conditioning | |||

| TBI | 812 | 1 | |

| Bu | 293 | 0.82 (0.61-1.11) | 0.19 |

| Significant Covariates: | |||

| Recipient age at HCT | |||

| 18-34 | 495 | 1 | |

| 35-60 | 610 | 1.59 (1.21-2.08) | 0.0009 |

| Cytogenetics | |||

| Poor, Ph+ | 415 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| Poor, Ph− | 155 | 0.74 (0.50-1.09) | 0.13 |

| Other (including normal) | 438 | 0.49 (0.36-0.67) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 97 | 0.69 (0.44-1.09) | 0.11 |

| Time to achieve CR1 | |||

| ≤8 weeks | 574 | 1 | 0.037 |

| >8 weeks | 437 | 1.35 (1.03-1.77) | 0.028 |

| Missing | 94 | 1.62 (0.95-2.79) | 0.079 |

| Time from CR1 to HCT (for CR1 cases) | |||

| ≤6 months | 676 | 1 | 0.0002 |

| >6 months | 109 | 1.81 (1.22-2.67) | 0.003 |

| N/A, CR2 | 280 | 1.83 (1.29-2.61) | 0.0008 |

| Missing | 40 | 0.73 (0.29-1.85) | 0.51 |

| Relapse | |||

| Main variable: | |||

| Conditioning | 812 | 1 | |

| TBI | |||

| Bu | 293 | 1.46 (1.15-1.85) | 0.0016 |

| Significant Covariates | |||

| Disease status at HCT | |||

| CR1 | 825 | 1 | |

| CR2 | 280 | 1.79 (1.41-2.27) | <.0001 |

| Time to achieve CR1 | |||

| ≤8 weeks | 574 | 1 | 0.11 |

| >8 weeks | 437 | 1.27 (1.01-1.61) | 0.042 |

| Missing | 94 | 0.99 (0.65-1.50) | 0.95 |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; TBI, total body irradiation; Bu, busulfan; CR, complete remission; Ph, Philadelphia; DFS, disease-free survival; TRM, treatment-related mortality; N, number; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval

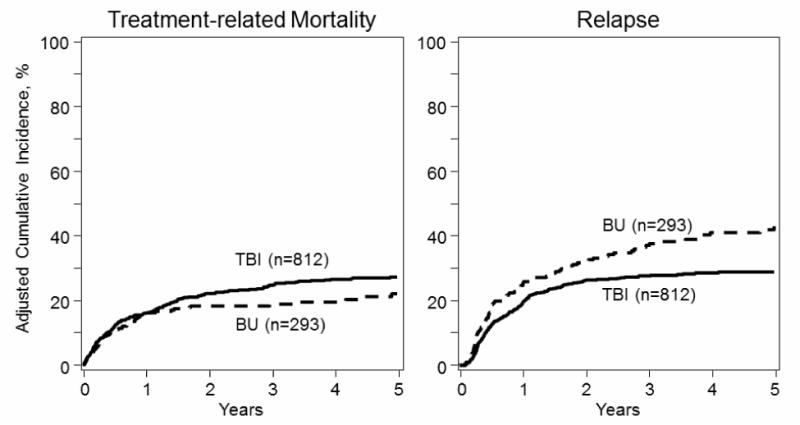

Treatment-related mortality and graft vs. host disease

Patients in the BU-based group experienced less late TRM compared with the TBI group, with the difference becoming apparent only after the first year following HCT, and TRM was significantly lower at 3 years, 19% vs. 25%, p=.04 (Figure 2, Table 3). However, in multivariate analysis, the conditioning regimen was not significantly associated with TRM (Table 2). Factors associated with increased TRM were age ≥35 years (RR 1.59, 95% CI: 1.21-2.08, p=.001), longer time to achieve CR1 (RR 1.35, 95% CI: 1.03-1.77, p=.028), and greater time from CR1 to HCT for the CR1 group (RR 1.81, 95% CI: 1.22-2.67, p=.003). Additionally, standard risk karyotype was associated with significantly lower TRM compared with Ph+ (RR 0.49, 95% CI: 0.36-0.67, p <.0001). However, there was no difference in risk of TRM between the Ph+ and non-Ph poor risk group (Table 2). The cause of death by treatment cohort is listed in Table 4. Non-relapse causes of death were less frequent in the BU group compared with TBI: pneumonitis or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (0.7% vs. 5%), infection (5.9% vs. 13%) and organ failure (8.8% vs.12%). Relapse as a cause of death was more frequent in the BU group (57 vs. 45%). The reported death from secondary malignancy was similar in both groups at 0.7% but the follow up is short.

Figure 2. Adjusted cumulative incidence of treatment-related mortality and relapse in adult ALL patients by transplant conditioning regimen.

Conditioning was not significantly associated with TRM in multivariate analysis. However, patients in the BU group had increased 1.46 (95% C.I.: 1.15-1.85) relative risk for relapse, p=.002, compared with patients in the TBI group.

Abbreviations: TBI, total body irradiation; Bu, busulfan; N, number; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia

Table 4.

Causes of death by treatment group

| Cause of Death, No (%) | TBI, N=377 deaths | BU, N=135 deaths |

|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 170 (45) | 77 (57) |

| Graft failure | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| GVHD | 50 (13) | 16 (11.8) |

| Infection | 51 (13) | 8 (5.9) |

| Interstitial pneumonitis or ARDS | 19 (5) | 1 (0.7) |

| Organ failure | 45 (12) | 12 (8.8) |

| Secondary malignancy | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Hemorrhage | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) |

| Accident | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Vascular | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.7) |

| Other | 23 (6.1) | 15 (11) |

| Unknown | 9 (2.4) | 3 (2.2) |

Abbreviations: GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; TBI, total body irradiation; BU, busulfan; N, number; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome

The cumulative incidence of aGVHD at day 100, grades II-IV and III-IV were 47% vs. 40%, p=.08, and 12% vs. 16%, p=.04, for the BU vs. TBI-based groups, respectively. In univariate analysis, cGVHD was marginally lower in the BU-based group (49% vs. 55%, p=.07) (Table 3). In multivariate analysis, the transplant conditioning group was not significant for aGVHD risk, but the use of BU-based regimens was associated with marginally less risk of cGVHD (RR 0.83, 95% CI: 0.68-1.01, p=.059).

Relapse

Patients in the BU group experienced significantly more relapse compared with the TBI group, 37% vs. 28% at 3 years, p=.01 (Figure 2, Table 3). In multivariate analysis, the use of BU-based conditioning was associated with a 1.46 RR for relapse, 95% CI: 1.15-1.85, p=.002 (Table 2). Additional factors significantly associated with increased risk for relapse were HCT in CR2 (RR 1.79, 95% CI: 1.41-2.27, p <.0001) and longer time to achieve CR1 (RR 1.27, 95% CI: 1.01-1.61, p=.04) (Table 2).

Subset analysis for patients 50-60 years-old

One of the reasons for investigating non-TBI conditioning regimens is to evaluate a potentially safer approach for older patients. We conducted a subset analysis for patients aged 50-60 years-old, and treatment characteristics and outcomes are listed in Table 5. The main transplant outcomes were similar with either transplant regimen in this age group (Table 5). It is important to note that our study was not adequately powered to examine the two treatment approaches in this older age or other subgroups.

Table 5.

Subset analysis for patients 50-60 years, characteristics and outcomes

| Variable | TBI, N(%) | BU, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 136 | 73 |

| Male | 73 (54) | 37 (51) |

| KPS >=90% | 81 (60) | 48 (66) |

| Disease stage at HCT | ||

| CR1 | 118 (87) | 64 (88) |

| CR2 | 18 (13) | 9 (12) |

| Cytogenetics | ||

| Poor, Ph+ | 67 (49) | 41 (56) |

| Poor, Ph− | 22 (16) | 11 (15) |

| Other | 40 (29) | 17 (23) |

| Med.wks achieve CR1(range) | 6 (1-47) | 11 (3-45) |

| Time from CR1 to HCT | ||

| ≤6 months | 103 (76) | 51 (69) |

| >6 months | 12 (9) | 9 (12) |

| PK for Bu dosing | 0 | 55 (75) |

| Donor type | ||

| SIB | 65 (48) | 44 (60) |

| MUD | 71 (52) | 29 (40) |

| Graft type | ||

| Bone marrow | 28 (21) | 8 (11) |

| Peripheral blood | 108 (79) | 65 (89) |

| Med. Mo. fu survivors (range) | 60 (3-120) | 38 (6-96) |

| Outcomes, 3-year | Prob (95%CI) | Prob(95%CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 26 (19-34)% | 30 (19-42)% | 0.6 |

| TRM | 34 (26-43)% | 29 (20-41)% | 0.84 |

| DFS | 40 (31-49)% | 41 (29-53)% | 0.81 |

| OS | 40 (32-49)% | 49 (37-61)% | 0.55 |

Abbreviations: TBI, total body irradiation; BU, busulfan; N, number; KPS, Karnosfky performance status; CR, complete remission; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; PK, pharmacokinetics; SIB, sibling; MUD, matched unrelated donor; Med, median; M, month; fu, follow up; TRM, treatment related mortality; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival; Prob, probability; CI, confidence interval

DISCUSSION

To avoid the well-documented short- and long-term effects of TBI, non-TBI preparative regimens based on BU are being explored. We demonstrated similar overall survival between these two treatment approaches. The BU-based regimens appeared better tolerated, with decreased TRM. Decreased grades III-IV acute GVHD and chronic GVHD were observed in the BU compared with TBI group, despite a higher proportion of patients receiving peripheral blood grafts in the BU group. Of note, the difference in TRM was most apparent after the first year following HCT, and may in part be related to the increased rate of chronic GVHD observed in the TBI group. Unfortunately, we did not have the data to describe the regimen-related toxicity profile, which was likely different between the two groups. However, in reviewing non-relapse causes of death, there were more cases of fatal pneumonitis or ARDS in the TBI group versus the BU group (0.7% vs 5%); the rate for fatal secondary malignancy was less than 1% and similar in both groups. But disappointingly, the relapse rate was significantly higher with the non-TBI, BU-based conditioning regimens. Similar findings were noted in a recent EBMT report comparing thiotepa-based chemotherapy only conditioning with myeloablative Cy-TBI conditioning prior to allogeneic HCT for adult ALL(26). In this retrospective, matched pair analysis, the 2-year leukemia-free survival and OS rates were comparable at 33% vs. 39% and 47% vs. 49% for thiotepa-based vs. TBI-based regimens, respectively. In multivariate analysis for patients in CR1, thiotepa treated patients had a trend for inferior LFS (HR 1.44, 95% CI, 0.98-2.12, p=.06) and increased rate of relapse (HR 1.78, 95% CI, 1.07-2.95, p=.03), but this did not impact OS (26).

Our findings differ from earlier retrospective (5) and prospective studies (6) of non PK-targeted, oral BU in combination with Cy which was associated with significantly higher rates of TRM compared with Cy-TBI in children with ALL undergoing HCT. In these earlier studies, leukemia relapse rates were similar between the treatment arms, but OS favored TBI due to the high TRM with BU-Cy. PK-guided, i.v. BU administration, which ensures a more predictable dose delivery, may contribute to the good safety profile noted in this study. Since the majority of patients received PK-directed BU therapy, we could not investigate the effect of PK guidance in the multivariate analysis due to the very few patients who did not receive PK-guidance. However, PK guidance was associated with significantly better OS within the BU group. Notably, our results did not corroborate the finding of similar relapse incidence in conditioning without TBI that was observed in the studies conducted in children, but there are established different patterns of relapse in adult patients with ALL(27).

The fundamentally different patient populations compared with each treatment approach was one of the biggest limitations of this study. In addition to ATG use and Ph+ patients, the BU patients were older, had more resistant disease taking longer to achieve CR 1, and took longer to receive HCT. Furthermore, BU-based therapy was used more frequently in recent years, and consequently TKI therapy post HCT was used more frequently in Ph+ patients in this group. Of note, multivariate analysis excluding Ph+ patients showed similar outcomes (data not shown). Furthermore, the majority of the BU patients (94%) were treated at either of 2 large transplant centers, introducing potential for center bias into the analysis. Finally, data on minimal residual disease was not available, and therefore we cannot know if there was an imbalance of positive MRD between the two treatment groups.

Notably, our analysis was not powered to compare outcomes with each treatment approach in patients undergoing HCT in CR1 vs. CR2, or younger vs. older patients. In a subset analysis of patients ≥50 years, for whom non-TBI based regimens are often elected, all post HCT outcomes were similar with either approach. Similar observations were reported in a retrospective analysis of myeloablative allogeneic HCT in adults with T-ALL. In this study reported by the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), 601 patients with T-ALL were transplanted with either TBI-based (87%) or non- TBI-based regimens (13%). Patients receiving TBI had lower risk for relapse, but the high rate of TRM rate in the TBI group for patients greater than 35 years (38% vs. 9% for chemo-only), precluded any survival benefit for TBI in the older patients.(28)

Furthermore, our study was not powered to investigate the optimal BU-based regimen. Increasing studies show that HCT outcomes are different with specific BU-based regimens. In a prospective, multicenter study in adults aged 40-65 years undergoing HCT for AML, patients were randomized to receive either i.v BU 0.8 mg/kg × 16 doses combined with Cy 120 mg/kg or same i.v. BU combined with Flu 160 mg/kg. The 1-year TRM rate was 7.9% for BU-Flu vs. 17.2 for the BU-Cy, p=.026, with similar relapse rates, suggesting differences in tolerance between the two regimens.(29) Similarly, in a single center pediatric study including mainly ALL patients, Bartelink et al reported data for two consecutive groups of children treated with BU-Cy between 2005-2008, and then BU-Flu between 2009-2012. The BU-Flu group had less observed toxicity with lower rates of lung injury, VOD, infection, and chronic GVHD.(30)

Our findings need to be further investigated in a prospective study. Still, our analysis provides useful information to the existing literature for transplant approaches to adults with ALL. Within the limitations of a retrospective registry analysis, we have shown for the first time that OS is comparable for BU and TBI-based myeloablative conditioning in adults undergoing HCT for ALL. The optimal HCT conditioning approach for each patient is based on an individual patient’s risk for relapse and projected TRM. The incorporation of i.v., PK-guided BU has resulted in decreased rates of TRM compared with older studies that used the oral formulation of BU, and further investigations, such as post-transplant maintenance, are needed to mitigate the relapse rate with chemotherapy-only regimens. The use of TBI-based therapy confers good disease control at the expense of greater TRM, including GVHD, and further strategies to decrease TRM are needed with this approach.

Highlights.

TBI and BU-based preparative regimens confer equivalent survival post HCT in adult ALL.

More relapse, trend for less cGVHD for BU-based regimens in multivariate analysis.

TBI-based regimens confer good disease control, but trend for more TRM.

Acknowledgments

CIBMTR Support List

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24- CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-15-1-0848 and N00014-16-1-2020 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Alexion; *Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Be the Match Foundation; *Bluebird Bio, Inc.; *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology; *Celgene Corporation; Cellular Dynamics International, Inc.; *Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.; Genzyme Corporation;

*Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; *Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac, GmbH; MedImmune; The Medical College of Wisconsin; *Merck & Co, Inc.; Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.;

*Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Neovii Biotech NA, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. – Japan; PCORI; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc; *Sanofi US; *Seattle Genetics; *Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc.; University of Minnesota; and *Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

*Corporate Members

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Additional Contributing authors:

William Hogan, Minoo Battiwalla, Edward Copelan, Gerhard Hildebrandt, Sid Ganguly, Navneet Majhail, Ann Woolfrey, Ian Nivison-Smith, Mark Hertzberg, Miguel Angel Diaz, Ann Jakubowski, Celalettin Ustun, Agnes Yong, Cesar Freytes, Zachariah DeFilipp, Yoshi Inamoto, Jean-Yves Cahn, Bipin Savani, Jean Yared, Ashish Bajel, Ulrike Bacher, Geoffrey Uy, David Rizzieri, Matthew Wieduwilt, Kirk Schultz, Michael Grunwald, Rammurti Kamble, Muna Qayed, Jonathan Brammer, Karen Ballen, Nandita Khera, Harry Schouten, Marc Bierings, Christopher Kanakry, William Allen Wood, Ayman Saad, Lynn Savoie, Betty Ky Hamilton, Mahmoud Aljurf, Ravi Vij, Attaphol Pawarode, Richard Olsson, B. Mona Wirk, Amer Beitinjaneh, Sachiko Seo, Jan Cerny, Gorgun Akpek, Maxim Norkin, Taiga Nishihori, Aleksandr Lazaryan, Mitchell Sabloff

COI: The authors report no conflicts of interest in the analysis or report of the data.

References

- 1.Marks DI, Forman SJ, Blume KG, Perez WS, Weisdorf DJ, Keating A, et al. A comparison of cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation with etoposide and total body irradiation as conditioning regimens for patients undergoing sibling allografting for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first or second complete remission. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006 Apr;12(4):438–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.12.029. Epub 2006/03/21.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, Tallman MS, Buck G, Fielding AK, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993) Blood. 2008 Feb 15;111(4):1827–33. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116582. Epub 2007/12/01.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutton L, Kuentz M, Cordonnier C, Blaise D, Devergie A, Guyotat D, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission: factors predictive of transplant-related mortality and influence of total body irradiation modalities. Bone marrow transplantation. 1993 Dec;12(6):583–9. Epub 1993/12/01.eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliansky DM, Camitta B, Gaynon P, Nieder ML, Parsons SK, Pulsipher MA, et al. The role of cytotoxic therapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia: update of the 2005 evidence-based review. ASBMT Position Statement. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012 Jul;18(7):979–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.03.011. Epub 2012/04/12.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies SM, Ramsay NK, Klein JP, Weisdorf DJ, Bolwell B, Cahn JY, et al. Comparison of preparative regimens in transplants for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000 Jan;18(2):340–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.340. Epub 2000/01/19.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunin N, Aplenc R, Kamani N, Shaw K, Cnaan A, Simms S. Randomized trial of busulfan vs total body irradiation containing conditioning regimens for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium study. Bone marrow transplantation. 2003 Sep;32(6):543–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704198. Epub 2003/09/04.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashyap A, Wingard J, Cagnoni P, Roy J, Tarantolo S, Hu W, et al. Intravenous versus oral busulfan as part of a busulfan/cyclophosphamide preparative regimen for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: decreased incidence of hepatic venoocclusive disease (HVOD), HVOD-related mortality, and overall 100-day mortality. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8(9):493–500. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12374454. Epub 2002/10/11.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell JA, Tran HT, Quinlan D, Chaudhry A, Duggan P, Brown C, et al. Once-daily intravenous busulfan given with fludarabine as conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplantation: study of pharmacokinetics and early clinical outcomes. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8(9):468–76. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12374451. Epub 2002/10/11.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson BS, Thall PF, Madden T, Couriel D, Wang X, Tran HT, et al. Busulfan systemic exposure relative to regimen-related toxicity and acute graft-versus-host disease: defining a therapeutic window for i.v. BuCy2 in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2002;8(9):477–85. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2002.v8.pm12374452. Epub 2002/10/11.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geddes M, Kangarloo SB, Naveed F, Quinlan D, Chaudhry MA, Stewart D, et al. High busulfan exposure is associated with worse outcomes in a daily i.v. busulfan and fludarabine allogeneic transplant regimen. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008 Feb;14(2):220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.10.028. Epub 2008/01/25.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ansari M, Theoret Y, Rezgui MA, Peters C, Mezziani S, Desjean C, et al. Association between busulfan exposure and outcome in children receiving intravenous busulfan before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Therapeutic drug monitoring. 2014 Feb;36(1):93–9. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3182a04fc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Labopin M, Bazarbachi A, Socie G, Kroeger N, Blaise D, et al. Higher busulfan dose intensity appears to improve leukemia-free and overall survival in AML allografted in CR2: An analysis from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Leukemia research. 2015 Sep;39(9):933–7. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bredeson C, LeRademacher J, Kato K, Dipersio JF, Agura E, Devine SM, et al. Prospective cohort study comparing intravenous busulfan to total body irradiation in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2013 Dec 5;122(24):3871–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartelink IH, Lalmohamed A, van Reij EM, Dvorak CC, Savic RM, Zwaveling J, et al. Association of busulfan exposure with survival and toxicity after haemopoietic cell transplantation in children and young adults: a multicentre, retrospective cohort analysis. The Lancet Haematology. 2016 Nov;3(11):e526–e36. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30114-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Russell JA, Savoie ML, Balogh A, Turner AR, Larratt L, Chaudhry MA, et al. Allogeneic transplantation for adult acute leukemia in first and second remission with a novel regimen incorporating daily intravenous busulfan, fludarabine, 400 CGY total-body irradiation, and thymoglobulin. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007 Jul;13(7):814–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.03.003. Epub 2007/06/21.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santarone S, Pidala J, Di Nicola M, Field T, Alsina M, Ayala E, et al. Fludarabine and pharmacokinetic-targeted busulfan before allografting for adults with acute lymphoid leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011 Oct;17(10):1505–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.011. Epub 2011/03/10.eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kebriaei P, Basset R, Ledesma C, Ciurea S, Parmar S, Shpall EJ, et al. Clofarabine combined with busulfan provides excellent disease control in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012 Dec;18(12):1819–26. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.06.010. Epub 2012/07/04.eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kebriaei P, Bassett R, Lyons G, Valdez B, Ledesma C, Rondon G, et al. Clofarabine Plus Busulfan is an Effective Conditioning Regimen for Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Patients with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: Long-Term Study Results. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016 Nov 02; doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weisdorf D, Spellman S, Haagenson M, Horowitz M, Lee S, Anasetti C, et al. Classification of HLA-matching for retrospective analysis of unrelated donor transplantation: revised definitions to predict survival. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008 Jul;14(7):748–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giralt S, Ballen K, Rizzo D, Bacigalupo A, Horowitz M, Pasquini M, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimen workshop: defining the dose spectrum. Report of a workshop convened by the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009 Mar;15(3):367–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone marrow transplantation. 1995 Jun;15(6):825–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. The American journal of medicine. 1980 Aug;69(2):204–17. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moorman AV, Chilton L, Wilkinson J, Ensor HM, Bown N, Proctor SJ. A population-based cytogenetic study of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010 Jan 14;115(2):206–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Zhang MJ. SAS macros for estimation of direct adjusted cumulative incidence curves under proportional subdistribution hazards models. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine. 2011 Jan;101(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Loberiza FR, Klein JP, Zhang MJ. A SAS macro for estimation of direct adjusted survival curves based on a stratified Cox regression model. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine. 2007 Nov;88(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eder S, Canaani J, Beohou E, Labopin M, Sanz J, Arcese W, et al. Thiotepa-based conditioning versus total body irradiation as myeloablative conditioning prior to allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A matched-pair analysis from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. American journal of hematology. 2017 Jun 14; doi: 10.1002/ajh.24823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 2008 Mar 22;371(9617):1030–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cahu X, Labopin M, Giebel S, Aljurf M, Kyrcz-Krzemien S, Socie G, et al. Impact of conditioning with TBI in adult patients with T-cell ALL who receive a myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a report from the acute leukemia working party of EBMT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2016 Mar;51(3):351–7. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2015.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rambaldi A, Grassi A, Masciulli A, Boschini C, Mico MC, Busca A, et al. Busulfan plus cyclophosphamide versus busulfan plus fludarabine as a preparative regimen for allogeneic haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology. 2015 Nov;16(15):1525–36. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartelink IH, van Reij EM, Gerhardt CE, van Maarseveen EM, de Wildt A, Versluys B, et al. Fludarabine and exposure-targeted busulfan compares favorably with busulfan/cyclophosphamide- based regimens in pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: maintaining efficacy with less toxicity. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2014 Mar;20(3):345–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]