Abstract

Recent experiments have set a new record for the transition temperature at which a material (hydrogen sulfide, H3S) becomes superconducting. Moreover, a pronounced isotope shift of TC in D3S is evidence of an existence of phonon-mediated pairing mechanism of superconductivity that is consistent with the well established Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer scenario. Herein, we reported a theoretical studies of the influence of the substitution of 32S atoms by the heavier isotopes 33S, 34S and 36S on the electronic properties, lattice dynamics and superconducting critical temperature of H3S. There are two equally fundamental results presented in this paper. The first one is an anomalous sulfur-derived superconducting isotope effect, which, if observed experimentally, will be subsequent argument that proves to the classical electron-phonon interaction. The second one is fact that critical temperature rise to extremely high value of 242 K for H336S at 155 GPa. This result brings us closer to the room temperature superconductivity.

Introduction

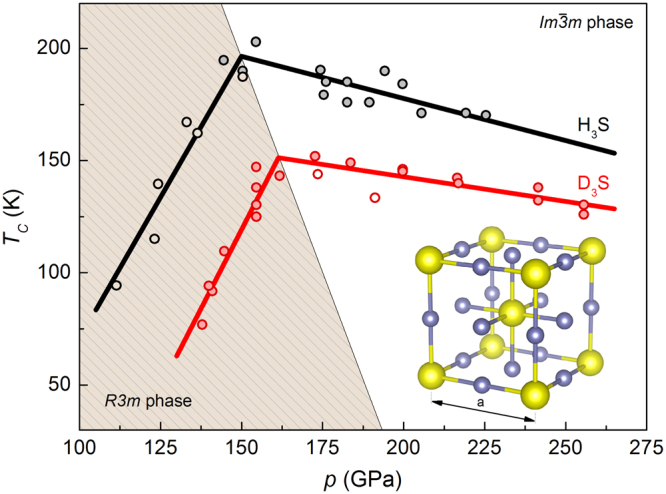

According to the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) theory of superconductivity1,2, achieving high-critical temperature (TC) requires the simultaneous presence of high-frequency phonon modes, large electron-phonon coupling and high electronic density of states (DOS) at the Fermi level3. These conditions are fully met in pristine hydrogen and in some previously studied hydrogen-rich systems4–14. Back in the year 1968, Ashcroft first proposed that solid hydrogen would be metallized at high pressure and has the potential to be a room-temperature superconductor15. Later, due to the fact that pressure of pristine hydrogen metallization was too high for experimental verification (~500 GPa16), Ashcroft extended his idea into hydrogen-rich compounds17. These materials were expected retain the superconducting properties of pure hydrogen but metallize at pressures significantly lower and reachable by current diamond anvil cell compression technique owing to the chemical pre-compression5,16. There is an essential hope that these materials can conduct electrical current at room-temperature without loss of energy18–21. Based on this idea, a lot of extensive theoretical studies have been carried out22–26. Most importantly, this has been confirmed experimentally that compressed hydrogen sulfide (H3S) becomes metallic and has a highest superconducting critical temperature ever recorded (203 K at 155 GPa)5,8. The experimental relationship between critical temperature and pressure is presented in Fig. 1. Moreover, the directly observed expulsion of external magnetic field from compressed H3S superconducting sample (Meissner effect) and the strong isotope shift of TC in sulfur deuteride (isotope effect) suggest that we deal with a conventional phonon-mediated superconductivity5,27. Recently, Bianconi et al. suggested that H3S is a multiband metal and Lifshitz transitions could occur by increasing pressure28,29, however, these assumptions have not been confirmed or disapproved yet in experimental measurements.

Figure 1.

The experimental values of the critical temperature for H3S and D3S5,8. Inset presents the crystal structure for which the record high TC was observed8,35.

Currently, the extensive researches on the possibility of increasing the value of TC to room temperature are conducting. Recently, generalizing the results on the whole family of the HnS-type compounds, we shown that the maximum value of TC can be equal to ~290 K30. Unfortunately, neither the pressure increase31 nor the taking into account the non-adiabatic effects32 do not allow to break the record established by the team led by Eremets5. Continuing the earlier study, in this paper we take into account the previously completely ignored pathway to increase transition temperature and set a new record for superconductivity. We investigate the influence of the sulfur isotope effect on the superconducting state in compressed hydrogen sulfide.

Theoretical model and computational methods

In this paper, the electronic properties, lattice dynamics and electron-phonon coupling were calculated using the first-principle pseudopotential plane-wave method based on the density functional theory through the Quantum-Espresso package33,34. The ultrasoft Vanderbilt pseudopotentials for S and H atoms were employed with a kinetic energy cut-off equal to 80 Ry. The electronic band structure calculations were performed for 32 × 32 × 32 Monkhorst-Pack k-mesh to sample the Brillouin zone with the Gaussian smearing of 0.03 Ry. The phonon dispersion and electron-phonon coupling matrices were computed within the framework of the linear-response method on the set of 8 × 8 × 8 q-point mesh for the first Brillouin zone integrations. The energy convergence and precision of all presented results are controlled by assuming the sufficiently small (10−16 Ry) threshold on the change in total energy.

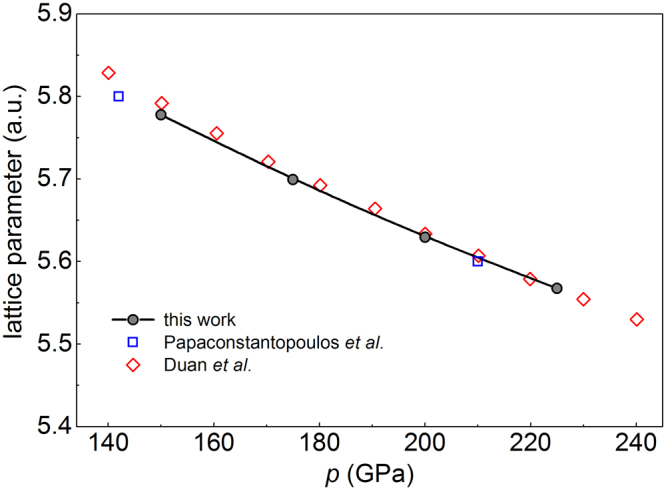

The X-ray diffraction experiments8 confirm that the superconducting phase of H3S is in good agreement with the theoretically predicted body-centred cubic structure35. The ball-and-stick model of cubic H3S structure under compression is shown in the inset of Fig. 1. To evaluate the lattice constant and phase stability of the investigated structure we performed total energy calculations and structural relaxations in a wide range of high pressure. The lattice constant and atomic positions were relaxed according to the atomic forces. This procedure was repeated until the forces on every atom of the unit cell were less than 1 meV/a.u. and the resulting stress less than 1 kbar. In this way, the fully relaxed structural parameters of H3S have been obtained. In Fig. 2, the calculated lattice constant as a function of pressure was presented and compared with other theoretical predictions35,36. These results coincide with very good accuracy with previous reports, consequently, for the pressure range where the high-TC was measured (155–225 GPa) we assume that structure is stable and we expect that the change of sulfur isotope mass can significantly influences on the superconducting state of H3S.

Figure 2.

Calculated lattice constant as a function of pressure. The open symbols correspond to the previously reported theoretical results35,36.

Results and Discussion

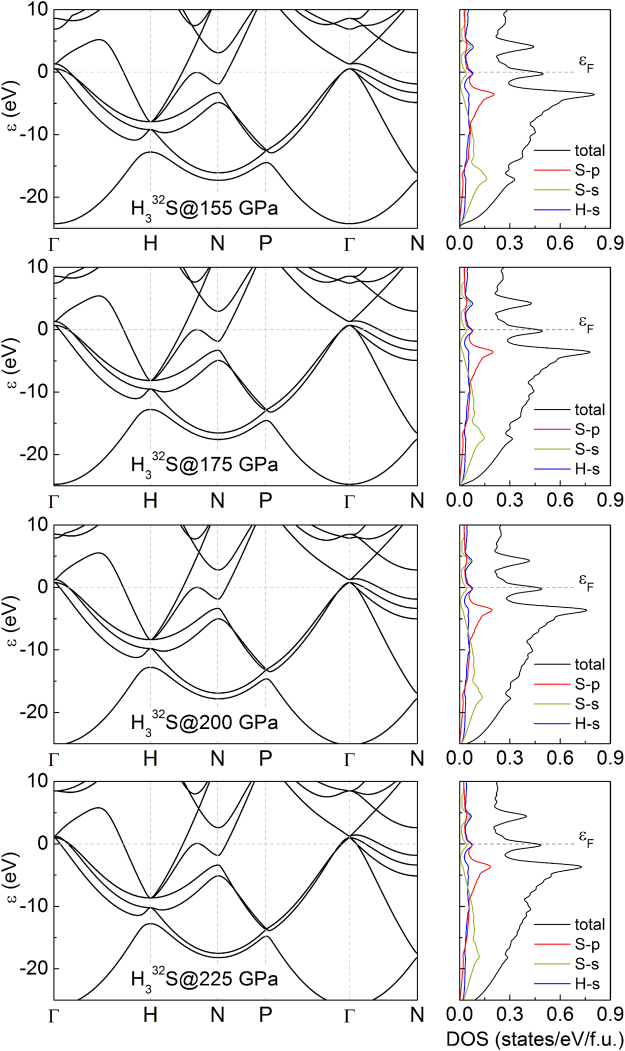

To analyze the electronic properties of H3S the electronic band structure and the partial density of states (DOS) were calculated. In Fig. 3 we can see the results for investigated pressures 155, 175, 200 and 225 GPa and for one of stable sulfur isotope 32S (94.99% natural abundance). The existence of electrons in the Fermi level indicates the metallic character of all cases. The van Hove singularity near the Fermi level can enhance the electron-phonon coupling strength and hence can be responsible for high-temperature superconductivity. Furthermore, very similar shape of electronic band structure and DOS are found in whole range of pressure. Also the change of sulfur isotope in elemental cell has no effect on the electronic properties of studied system. On this basis, we can suppose that phonons properties in hydrogen sulfide systems are actually responsible for change in their thermodynamic properties.

Figure 3.

Calculated electronic band structure and partial density of states (DOS) for H332S at selected pressures.

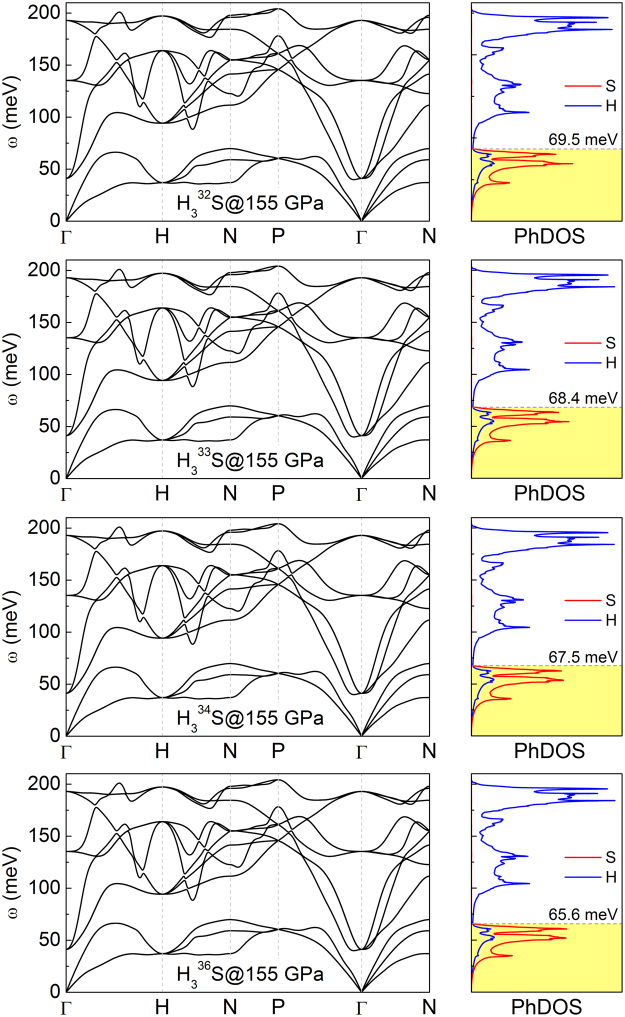

Figure 4 shows the calculated phonon band structure and projected phonon density of states (PhDOS). Phonon calculations did not give any imaginary frequency vibration mode in the whole Brillouin zone, indicating the dynamic stability of structure. Based on the PhDOS, we found that the vibration frequency is divided into two parts as a result of the different atomic masses of S and H atoms. The low-frequency bands mainly result from the vibrations of the S atoms, whereas the H atoms are mostly related to vibrations with higher frequency modes. Note that the contribution derived from sulfur is shifted towards the lower frequencies together with increasing S isotope mass. This should be reflected in the shape of the Eliashberg electron-phonon spectral function α2F(ω), which weights the phonon density of states with the coupling strengths and appropriately describes the pairing interaction due to phonons:

| 1 |

where

| 2 |

Figure 4.

Phonon dispersion and projected phonon density of states (PhDOS) for H3S with all stable sulfur isotopes. Results for pressure of 155 GPa.

Symbols N(0), γqν, and gqν(k, i, j) denote the density of states at the Fermi energy, the phonon linewidth, and electron-phonon matrix elements, respectively.

The Eliashberg spectral function, electron-phonon coupling constant λ and logarithmic average phonon frequency ωln are investigated to explore the possible record critical temperature of H3S. The calculated α2F(ω)/ω functions and integration of λ for H332S, H333S, H334S and H336S at 155 GPa are shown in Fig. 5. The main contribution to the electron-phonon coupling constant derived from hydrogen and it should be highlights that the H atoms play a significant role in the superconductivity of hydrogen sulfide. For H332S nearly 22% of λ originates from sulfur. With increasing mass of sulfur isotope, it is very interesting to note that, the part coming from S changes and finally decreases to 7% for H336S. The comparison of Eliashberg functions with phonon density of states shows that the square of the matrix element of the electron-phonon interaction averaged over the Fermi surface α2(ω) is responsible for complicated shape of the Eliashberg spectral functions. This may leads directly to the non-monotonic changes of magnitudes related to α2F(ω) such as λ, ωln, and critical temperature with increasing mass of sulfur isotope.

Figure 5.

The Eliashberg spectral functions for H3S at 155 GPa. Only the stable S isotopes was investigated (upper panel). The electron-phonon coupling parameter integral as a function of frequency (bottom panel). The percent contribution of λ originating from sulfur was marked for all cases.

The high vibrational phonon frequency and the strong electron-phonon coupling constant lead directly to a high superconducting critical temperature which was calculated using the Eliashberg formalism37,38. It should be noted that in literature TC is usually obtained using the simple approach proposed by McMillan or Allen and Dynes39,40, which represent the weak-coupling limit of the more elaborate Eliashberg approach37. In our previous papers41,42, we proved that the McMillan or Allen-Dynes-modified McMillan formulas and Eliashberg equations lead to similar results for small λ and Coulomb pseudopotential μ★. For larger λ and μ★, however, the analytical formulas predicts underestimated TC values. In the case of the hydrogen sulfide the electron-phonon interaction is strong, hence the analytical formulas are inappropriate. The isotropic Migdal-Eliashberg equations were solved in a numerical way43 using 2201 Matsubara frequencies ωn = (π/β)(2n−1), where n = 0, ±1, ±2, …, ±1100, and a Coulomb pseudopotential which was chosen to match the measured value of TC for standard S atomic weight of 32.06 u44.

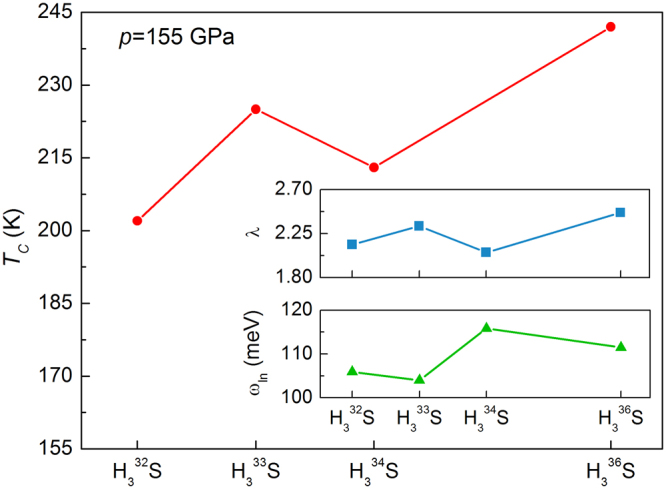

Such an assumption ensures the stability of the numerical solutions for T ≥ 1 K. The superconducting transition temperature was estimated to be in the range of 202–242 K at 155 GPa. The calculated TC, λ and ωln for H332S, H333S, H334S and H336S at 155 GPa are summarized in Fig. 6. It is very interesting to note that TC is strongly correlated with λ and despite decrease in ωln for H336S, λ increases resulting in an enhanced TC to record value of 242 K.

Figure 6.

Critical temperature calculated for investigated systems at 155 GPa. Insets present behavior of λ and ωln.

The isotope effect of superconducting critical temperature is best described in terms of the isotope effect coefficient α. For experimental results of hydrogen and deuterium sulfide at p = 155 GPa we have α = 0.4723. This value is very close to the theoretical value of 0.5 predicted within the framework of the BCS scenario. In this paper, for the most extreme case of sulfur isotopes at 155 GPa we have the following relation:

| 3 |

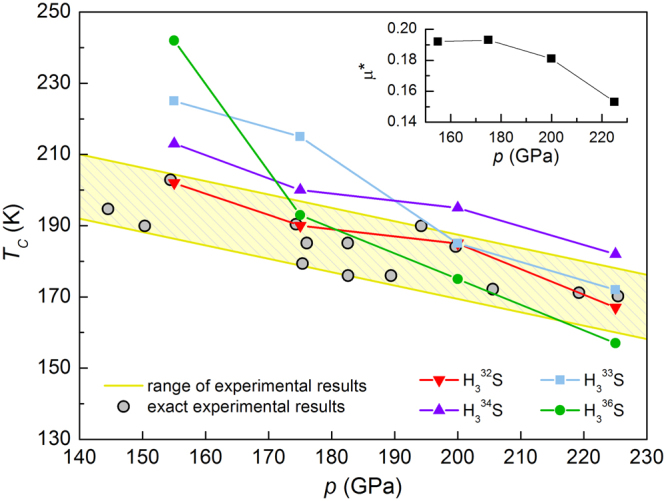

where and are the atomic mass of 32S and 32S isotope, respectively. Contrary to most superconducting materials, the calculated isotope coefficient is negative α = −1.5. The inverse and nontrivial behavior can be also observed for other isotopes and higher pressures, as shown in Fig. 7. On the other hand, some other systems also display values that are smaller than zero. For example the inverse superconducting isotope coefficient has been observed in uranium (α = −2)45, metal hydride PdH (α = −0.25)46 or lithium where α sign changes with increasing pressure47. Let us strongly emphasize, however, that the isotope effect in superconductivity is taken as evidence for phonon mediation. Coming back to the Fig. 7, we can additionally observed that with increasing pressure the critical temperature decreasing which is in a general agreement with the trend established by the experimental results. Moreover, it should be emphasized that correctness of our methods and numerical calculations was confirmed by comparison the obtained results with the previous ones for the natural isotope concentration of sulfur12,13,35,48. To benchmark the validity of the results obtained in the present work, in next section we have shown the calculated electronic structure and phonon dispersions together with the results previously reported by Duan et al.35. Moreover, we examined the isotope effect for H3S and D3S.

Figure 7.

Pressure dependence of the superconducting critical temperature measured5,8 and calculated for stable isotopes of sulfur. Inset presents the Coulomb pseudopotential reproducing the experimental value of TC for standard S atomic weight of 32.06 u.

Proving correctness of the presented results

A benchmark study on correctness of our results was done to electronic structure and phonon dispersions which were collate with the results previously reported by Duan et al.35. This comparison for the natural isotope concentration of sulfur in H3S at 200 GPa was shown in Fig. 8. On this base we can found that here is almost exact coincidence which proves the correctness of the results reported in the present work.

Figure 8.

Comparison between our results (red lines) obtained for the natural isotope concentration of sulfur and the results previously reported by Duan et al.35 (open circles).

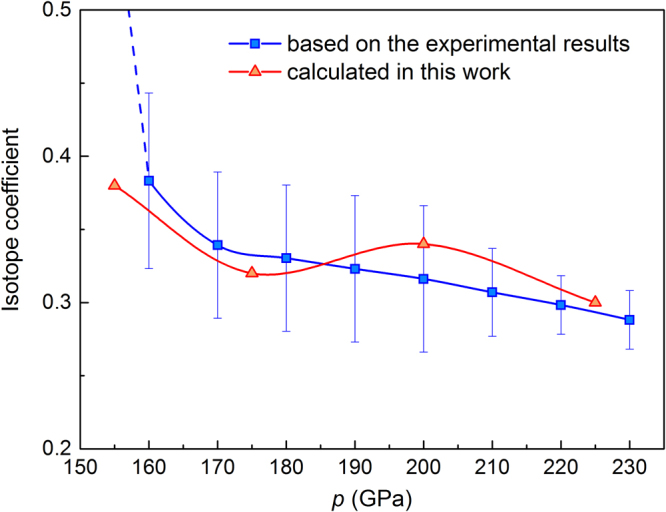

Moreover, we compared the isotope coefficient resulting from the experimental critical temperature of H3S and D3S (see Fig. 1) with our estimations conducted within the framework of the Eliashberg formalism. In both cases the isotope coefficient decreases with pressure which is connected with decreasing difference between critical temperature for H3S and D3S. As shown in Fig. 9, the very high level of consistency was achieved. This is another argument in favor of correctness and high-value of presented herein results.

Figure 9.

The isotope coefficient as a function of pressure calculated from the averaged experimental critical temperature of H3S and D3S at the same pressure (blue square) and our results (red triangles) obtained using Eliashberg formalism with Coulomb pseudopotential estimated for standard S atomic weight.

Conclusion

We reported the influence of the substitution of 32S atoms by the heavier isotopes 33S, 34S and 36S on the electronic properties, lattice dynamics and superconducting critical temperature in H3S. We observe that for a pressure of 155 GPa this substitution causes a strong (20%) enhancement of TC from 202 to 242 K. This unexpectedly high TC far exceeds the previous record of 203 K and bring us closer to achieving room-temperature superconductivity in hydrogen-rich materials at high pressure. The second very important and interesting result, reported in this paper, is uncommon sulfur isotope effect. We noted the strong negative isotope coefficient (α =−1.5) between H332S and H336S, and variation of the isotope effect with the increasing pressure.

We expected that our significant findings can stimulate future high-pressure experiments and that suggested pathway to increase TC can be appropriate to reach near-room-temperature superconductivity.

Acknowledgements

A.P. Durajski acknowledges the financial support from the Polish National Science Centre (NCN) under grant No. 2016/23/D/ST3/02109 and from the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP) under the scholarship START.

Author Contributions

R. Szczęśniak wrote the part of the code for numerical calculations and participated in writing the manuscript. A.P. Durajski designed and carried out the ab-initio calculations, collected data and drafted the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bardeen J, Cooper LN, Schrieffer JR. Microscopic theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957;106:162–164. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.106.162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardeen J, Cooper LN, Schrieffer JR. Theory of superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957;108:1175–1204. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.108.1175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lian C-S, Wang J-T, Duan W, Chen C. Phonon-mediated high-TC superconductivity in hole-doped diamond-like crystalline hydrocarbon. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1464. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01541-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan D, et al. Structure and superconductivity of hydrides at high pressures. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017;4:121. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drozdov AP, Eremets MI, Troyan IA, Ksenofontov V, Shylin SI. Conventional superconductivity at 203 kelvin at high pressures in the sulfur hydride system. Nature. 2015;525:73. doi: 10.1038/nature14964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu H, Li Y, Gao G, Tse JS, Naumov II. Crystal structure and superconductivity of PH3 at high pressures. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2016;120:3458–3461. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b12009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Errea I, et al. Quantum hydrogen-bond symmetrization in the superconducting hydrogen sulfide system. Nature. 2016;532:81. doi: 10.1038/nature17175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Einaga M, et al. Crystal structure of the superconducting phase of sulfur hydride. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:835–838. doi: 10.1038/nphys3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, et al. Dissociation products and structures of solid H2S at strong compression. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:020103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.020103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Einaga M, et al. Two-year progress in experimental investigation on high-temperature superconductivity of sulfur hydride. Jpnl. J. Appl. Phys. 2017;56:05FA13. doi: 10.7567/JJAP.56.05FA13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gor’kov LP, Kresin VZ. Pressure and high-TC superconductivity in sulfur hydrides. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25608. doi: 10.1038/srep25608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akashi R, Kawamura M, Tsuneyuki S, Nomura Y, Arita R. First-principles study of the pressure and crystal-structure dependences of the superconducting transition temperature in compressed sulfur hydrides. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;91:224513. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.91.224513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Errea I, et al. High-pressure hydrogen sulfide from first principles: A strongly anharmonic phonon-mediated superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015;114:157004. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.157004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa T, et al. Superconducting H5S5 phase in sulfur-hydrogen system under high-pressure. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23160. doi: 10.1038/srep23160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashcroft NW. Metallic hydrogen: A high-temperature superconductor? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1968;21:1748–1749. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.21.1748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dias RP, Silvera IF. Observation of the wigner-huntington transition to metallic hydrogen. Science. 2017;355:715–718. doi: 10.1126/science.aal1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ashcroft NW. Hydrogen dominant metallic alloys: High temperature superconductors? Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:187002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.187002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y. Near-room-temperature superconductivity in hydrogen sulfide. NPG Asia Mater. 2016;8:e236. doi: 10.1038/am.2015.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng X, Zhang J, Gao G, Liu H, Wang H. Compressed sodalite-like MgH6 as a potential high-temperature superconductor. RSC Adv. 2015;5:59292–59296. doi: 10.1039/C5RA11459D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H, Tse JS, Tanaka K, Iitaka T, Ma Y. Superconductive sodalite-like clathrate calcium hydride at high pressures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6463–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118168109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gor’kov LP, Kresin VZ. Colloquium: High pressure and road to room temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2018;90:011001. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.90.011001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Hao J, Liu H, Li Y, Ma Y. The metallization and superconductivity of dense hydrogen sulfide. J. Chem. Phys. 2014;140:174712. doi: 10.1063/1.4874158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durajski AP, Szczęśniak R, Pietronero L. High-temperature study of superconducting hydrogen and deuterium sulfide. Ann. Phys. (Berlin) 2016;528:358–364. doi: 10.1002/andp.201500316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortenzi L, Cappelluti E, Pietronero L. Band structure and electron-phonon coupling in H3S: A tight-binding model. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;94:064507. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.94.064507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szczęśniak D, Zemła TP. On the high-pressure superconducting phase in platinum hydride. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2015;28:085018. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/28/8/085018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, et al. Pressure-stabilized superconductive yttrium hydrides. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:9948. doi: 10.1038/srep09948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Troyan I, et al. Observation of superconductivity in hydrogen sulfide from nuclear resonant scattering. Science. 2016;351:1303–1306. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bussmann-Holder A, Köhler J, Simon A, Whangbo M, Bianconi A. Multigap superconductivity at extremely high temperature: A model for the case of pressurized H2S. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2017;30:151–156. doi: 10.1007/s10948-016-3947-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarlborg T, Bianconi A. Breakdown of the Migdal approximation at Lifshitz transitions with giant zero-point motion in the H3S superconductor. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24816. doi: 10.1038/srep24816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durajski AP, Szczęśniak R, Li Y. Non-BCS thermodynamic properties of H2S superconductor. Physica C. 2015;515:1. doi: 10.1016/j.physc.2015.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durajski AP, Szczęśniak R. First-principles study of superconducting hydrogen sulfide at pressure up to 500 GPa. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4473. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04714-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durajski AP. Quantitative analysis of nonadiabatic effects in dense H3S and PH3 superconductors. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38570. doi: 10.1038/srep38570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 395502 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Giannozzi P, et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2017;29:465901. doi: 10.1088/1361-648X/aa8f79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan D, et al. Pressure-induced metallization of dense (H2S)2H2 with high-TC superconductivity. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:6968. doi: 10.1038/srep06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papaconstantopoulos DA, Klein BM, Mehl MJ, Pickett WE. Cubic H3S around 200 GPa: An atomic hydrogen superconductor stabilized by sulfur. Phys. Rev. B. 2015;91:184511. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.91.184511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eliashberg GM. Interactions between electrons and lattice vibrations in a superconductor. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 1960;11:696. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carbotte JP. Properties of boson-exchange superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990;62:1027. doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.62.1027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McMillan WL. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors. Phys. Rev. 1968;167:331–344. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.167.331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen PB, Dynes RC. Transition temperature of strong-coupled superconductors reanalyzed. Phys. Rev. B. 1975;12:905–922. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.12.905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szczęśniak R, Jarosik M, Szczęśniak D. Pressure-induced superconductivity in the fcc phase of lithium: Strong-coupling approach. Physica B. 2010;405:4897–4902. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2010.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szczęśniak R, Szczęśniak D. Characterization of the high-pressure superconductivity in the Pnma phase of calcium. Phys. Status Solidi B. 2012;249:2194–2201. doi: 10.1002/pssb.201248032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szczęśniak R. The numerical solution of the imaginary-axis Eliashberg equations. Acta Phys. Pol. A. 2006;109:179. doi: 10.12693/APhysPolA.109.179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meija J, et al. Atomic weights of the elements 2013 (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl. Chem. 2016;88:265–291. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fowler RD, Lindsay JDG, White RW, Hill HH, Matthias BT. Positive isotope effect on the superconducting transition temperature of α-uranium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967;19:892–895. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.19.892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller RJ, Satterthwaite CB. Electronic model for the reverse isotope effect in superconducting Pd-H(D) Phys. Rev. Lett. 1975;34:144–148. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.34.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schaeffer AM, Temple SR, Bishop JK, Deemyad S. High-pressure superconducting phase diagram of 6Li: Isotope effects in dense lithium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:60–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412638112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flores-Livas JA, Sanna A, Gross EK. High temperature superconductivity in sulfur and selenium hydrides at high pressure. Eur. Phys. J. B. 2016;89:63. doi: 10.1140/epjb/e2016-70020-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]