ABSTRACT

The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is an essential regulator of placental development. To gain deeper insights into placental PPARγ signaling, we dissected its regulation of the Muc1 promoter. We find that, unlike prototypic target activation by heterodimeric receptors, which is either stimulated by or refractory to retinoid X receptor (RXR) ligands (rexinoids), the induction of Muc1 by liganded PPARγ requires RXRα but is inhibited by rexinoids. We demonstrate that this inhibition is mediated by the activation function 2 (AF2) domain of RXRα and that Muc1 activation entails altered AF2 structures of both PPARγ and RXRα. This unique regulation of Muc1 reflects specific coactivation of PPARγ-RXRα heterodimers by the transcription cofactor ligand-dependent corepressor (LCoR), corroborated by significant downregulation of Muc1 in Lcor-null placentas. LCoR interacts with PPARγ and RXRα in a synergistic fashion via adjacent noncanonical protein motifs, and the AF2 domain of ligand-bound RXRα inhibits this interaction. We further identify the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) as a critical regulator of placental development and a component of Muc1 regulation in cooperation with PPARγ, RXRα, and LCoR. Combined, these studies reveal new principles and players in nuclear receptor function in general and placental PPARγ signaling in particular.

KEYWORDS: KLF6, LCoR, PPARgamma, RXR, rexinoids, coactivators, transcription regulation

INTRODUCTION

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a nuclear receptor (NR) that functions as an obligate heterodimer with retinoid X receptors (RXRs) (1). PPARγ-RXR heterodimers bind to PPAR response elements (PPREs) in the regulatory regions of target genes and activate transcription in response to small lipophilic ligands, as well as the high-affinity thiazolidinedione (TZD) family of insulin sensitizers (2, 3). Aside from its well-established role in adipogenesis and energy metabolism (4), PPARγ is also an essential player in embryonic development, and its deficiency causes fetal death by the 10th day of gestation (embryonic day 10.0 [E10.0]) (5). At that stage, Pparg is expressed abundantly in the placenta and nowhere else in the embryo, and definitive genetic analyses have indicated that Pparg-null embryos die solely due to placental defects. These defects include failure of labyrinthine trophoblasts to differentiate and to interface tightly with the fetal endothelium, as well as disruption of the trophoblast-lined maternal blood spaces in the tissue, jointly abrogating placental vascularization (5). Overlapping phenotypic and gene expression patterns implicate RXRα as the primary RXR partner of placental PPARγ (5–7).

Despite its indispensable role in embryonic growth and survival, the placenta remains the least understood mammalian organ to date (8). We have been using PPARγ as a vantage point for insights into placental development. As PPARγ is a transcription factor, its placental functions ultimately derive from its regulation of target genes and should therefore be inferred from the functions of these targets (7). However, fine dissection of the transcriptional mechanics of PPARγ on its targets offers a plausible complementary approach, which may provide insights into placental regulatory networks irrespective of the function of the gene products. Previous studies of Muc1 promoter regulation by PPARγ revealed this potential by discovering mechanistic details that diverged from the canonical model of PPARγ action (9). Like typical PPARγ targets, the proximal Muc1 promoter responds strongly and in an RXRα-dependent manner to PPARγ and its ligand (9). Unlike the canonical model, however, detailed mutational analysis revealed that this response entails complex interactions in which a weak proximal PPRE acts as a basal silencer whose derepression by PPARγ unleashes robust induction of Muc1 by an upstream, non-PPAR-binding enhancer (9). The transcription factors and cofactors behind these combinatorial relationships may shed new light on regulatory networks in the placenta and, in turn, on placental development.

Here, deeper analyses of Muc1 promoter regulation by PPARγ revealed its unexpected suppression by rexinoids, which stands in stark contrast to its absolute dependence on RXRα. Moreover, Muc1 induction is mediated by noncanonical activation domain configurations of both PPARγ and RXRα. Surprisingly, we identified the transcription cofactor ligand-dependent corepressor (LCoR) (10) as a coactivator of PPARγ-RXRα on the Muc1 promoter. While LCoR possesses a canonical NR-binding LXXLL motif at its N terminus, which was shown to bind several NRs, PPARγ and RXRα interact synergistically with different LCoR sequences. In the presence of a ligand, the C-terminal activation function 2 (AF2) domain of RXRα inhibits these interactions, consistent with the suppression of Muc1 induction by rexinoids. We additionally found that the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 6 (KLF6), a known corepression partner of LCoR (11), is essential for normal placental development and synergizes with PPARγ, RXRα, and LCoR in Muc1 activation. In aggregate, this study reveals novel mechanisms of gene regulation by NRs and their cofactors, as well as new nodes in placental PPARγ signaling.

RESULTS

Muc1 induction by PPARγ and RXRα entails unique ligand and receptor configurations.

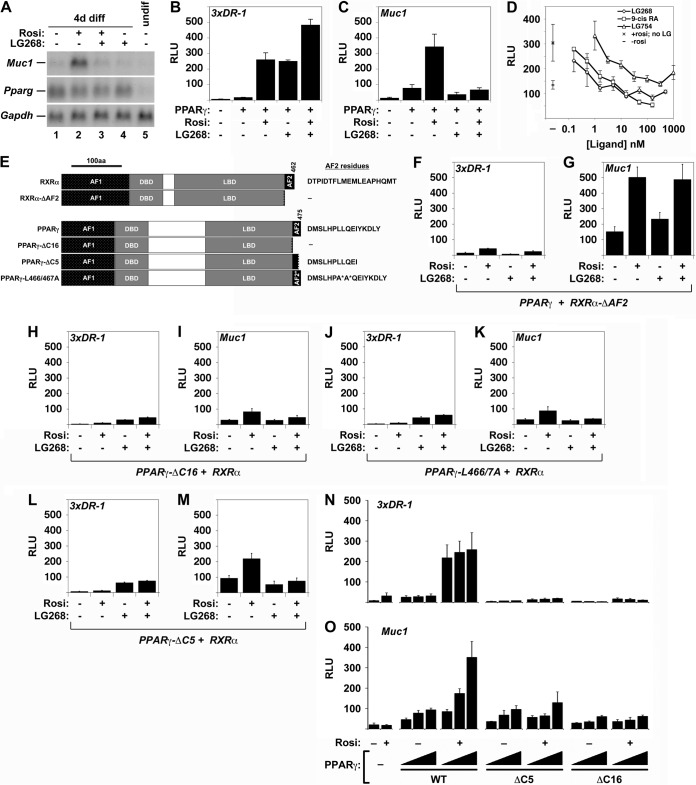

We previously demonstrated that, together with PPARγ, RXRα is indispensable for Muc1 expression in both whole placentas and heterologous reporter assays (9). Surprisingly, when testing whether the synthetic rexinoid LG100268 (LG268) can stimulate Muc1 similarly to other prototypic targets of RXR heterodimers (12), we observed dramatic inhibition of rosiglitazone (Rosi)-mediated Muc1 induction in differentiated trophoblast stem cells (TSC) (Fig. 1A, lane 2 versus 3). This phenomenon extended to heterologous reporter assays, in which LG268 recapitulated its documented ability to augment the induction of a synthetic, canonical 3xDR1 reporter by PPARγ and RXRα, both alone and in conjunction with Rosi (Fig. 1B) (12), but blunted Rosi-mediated stimulation of a Muc1 promoter-driven reporter (Fig. 1C). Suppression of Rosi-mediated Muc1 induction was observed with three structurally distinct rexinoids, LG268, LG100754 (LG754) (13), and 9-cis retinoic acid (9-cis-RA), with half-maximal inhibition at concentrations below the RXR-binding constants of all three compounds (Fig. 1D).

FIG 1.

Effects of rexinoids and RXRα and PPARγ AF2 domain mutations on Muc1 promoter activity. (A) Northern blot analysis of Muc1, Pparg, and Gapdh (normalization control) in cultures of the TSC line GFP-Trf differentiated for 4 days (4d diff) without treatment or in the presence of 1 μM Rosi, 1 μM LG268, or both, as well as an undifferentiated culture (undif), as indicated. (B) Relative light units (RLU) in extracts of CV1 cells transiently transfected with pCMX-βGAL, a 3xDR1-luciferase (3xDR1-luc) construct, and RXRα alone versus RXRα and PPARγ with the indicated combinations of Rosi and LG268, normalized to β-galactosidase activity. (C) Same as described for panel B, with a Muc1-luc construct instead of 3xDR1-luc. (D) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, Muc1-luc, RXRα, and PPARγ and treated with 1 μM Rosi and incremental concentrations of the distinct rexinoids LG268, 9-cis retinoic acid, and LG754, from 0.3 nM to 1 μM. Left, mean basal RLU ± standard error (SE) without RXR ligands: bottom, no Rosi (–); top, 1 μM Rosi (×). Right, mean RLU ± SE of experimental data. (E) Summary of RXRα and PPARγ AF2 domain mutants used. Exact AF2 residues present in each species are shown. (F to M) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, either 3xDR1-luc (F, H, J, L) or Muc1-luc (G, I, K, M), and the indicated RXRα or PPARγ combinations: full-length (FL)-PPARγ + RXRα-ΔAF2 (F, G), PPARγ-ΔC16 + FL-RXRα (H, I), PPARγ-L466A/L467A + FL-RXRα (J, K), and PPARγ-ΔC5 + WT RXRα (L, M). The results shown in panels B, C, and F to M are part of a transfection series performed side by side and are directly comparable. (N, O) Dose-dependent effects of FL-PPARγ, PPARγ-ΔC5, and PPARγ-ΔC16 on the Muc1 and DR1 reporters. Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, RXRα, and 3xDR1-luc (N) or Muc1-luc (O) and one to three quanta of the indicated PPARγ AF2 domain configurations (WT, ΔC5, and ΔC16), incubated in the absence or presence of 1 μM Rosi, as indicated; a filler plasmid (pCMX-GAL4N) was used to equalize the DNA concentration in reaction mixtures containing less than three quanta of the PPARγ variants. Bars and error bars show mean values and SE.

The ligand-dependent transcriptional activity of NRs resides in their C-terminal activation function 2 (AF2) domain (14, 15). We therefore compared the impacts of mutations in this domain (Fig. 1E) on the Muc1 promoter versus a canonical PPRE. Indeed, RXRα-ΔAF2, lacking the entire 19-amino-acid (aa)-long AF2 domain, lost the ability to support the activation of a canonical reporter (Fig. 1F), as previously reported (16). Remarkably, however, it substantially augmented the induction of the Muc1 promoter by PPARγ and Rosi and was refractory to inhibition by LG268 (Fig. 1G). This finding demonstrated that, while RXRα is indispensable for PPARγ-mediated Muc1 transcription (7, 9), its agonist-bound AF2 domain inhibits the process.

Contrary to the unanticipated dispensability of the RXRα AF2 domain, deleting the C-terminal 16 aa comprising the entire AF2 domain of PPARγ (PPARγ-ΔC16), which abolished activation of the canonical reporter, as expected (Fig. 1H), eliminated nearly all of its transactivation potential on Muc1 (Fig. 1I). The inactivating dual point mutation PPARγ-L466A/L467A (in which leucine residues at positions 466 and 467 were changed to alanine) (17) recapitulated this effect (Fig. 1J and K). Surprisingly, PPARγ-ΔC5, a mutant missing just the 5 C-terminal aa, was incapable of inducing the canonical reporter (Fig. 1L) but retained substantial potency toward Muc1, compromising its induction by only 35% (compare Fig. 1M to C). Moreover, in contrast to the almost-complete unresponsiveness of 3xDR1 to increasing concentrations of PPARγ-ΔC5 or PPARγ-ΔC16 (Fig. 1N), both truncated proteins, and to a larger extent PPARγ-ΔC5, elicited partial, dose-dependent, albeit ligand-refractory, induction of Muc1 (Fig. 1O). In aggregate, these results demonstrated that activation of the Muc1 promoter requires both PPARγ and RXRα, is suppressed by the AF2 domain of liganded RXRα, and depends on a novel configuration of the AF2 domain of PPARγ.

LCoR is a Muc1-specific coactivator of PPARγ and RXRα.

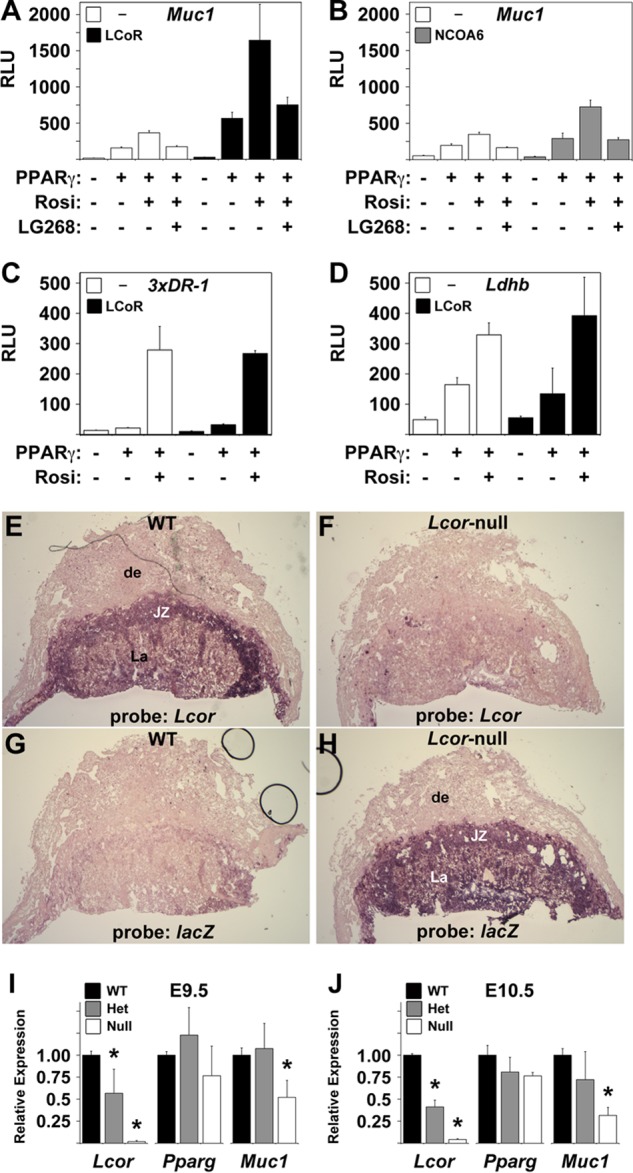

Considering the role of AF2 domains in NR-cofactor interactions, we hypothesized that the noncanonical mechanisms observed in the experiments described above reflect a unique mode of PPARγ-RXRα interaction with previously uncharacterized transcription cofactor complexes. To identify such regulators, we screened multiple known and putative NR cofactors for their impacts on Muc1 promoter activation by PPARγ and RXRα. Of the cofactors tested, LCoR (10) registered the strongest coactivation of PPARγ and RXRα on the Muc1 promoter, enhancing induction 3- to 5-fold (Fig. 2A). For comparison, nuclear receptor coactivator 6 (NCOA6), which we previously found to be a ubiquitous positive regulator of placental PPARγ-dependent genes in vivo (7), elicited a modest 2-fold enhancement of the Muc1 reporter in the same assay (Fig. 2B), in the same range as most other cofactors screened (data not shown). LCoR only registered an effect when both PPARγ and RXRα were present and augmented reporter activity proportionately with any combination of Rosi and LG268 (Fig. 2A). In line with the notion of promoter-specific cofactor recruitment, LCoR did not significantly coactivate reporters driven by the synthetic 3xDR1 or the Ldhb promoter (7) (Fig. 2C and D).

FIG 2.

LCoR is a Muc1-specific PPARγ coactivator. (A, B) LCoR strongly coactivates PPARγ on the Muc1 promoter. Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, Muc1-luc, and RXRα, with or without PPARγ as indicated, and treated with combinations of Rosi and LG268 (1 μM each), as marked, with or without cotransfection of LCoR (A) or NCOA6 (B). (C, D) LCoR has no effect on a 3xDR1 reporter or the Ldhb promoter. Same as described for panel A, with 3xDR1-luc (C) or Ldhb(2.7Kb)-luc (D) instead of Muc1-luc. (E to H) Lcor is expressed abundantly in all mouse placental layers. ISH of E11.5 WT (E, G) and Lcor-null (F, H) placentas with antisense riboprobes for Lcor (E, F) or the null-specific lacZ knock-in (G, H). de, decidua; JZ, junctional zone; La, labyrinthine layer. A similar staining pattern is observed at E16.5 (not shown). (I, J) Muc1 is significantly downregulated in Lcor-null placentas. RT-qPCR of Lcor, Pparg, and Muc1 in three or four litter-matched pools of three WT, Lcor+/−, or Lcor-null placentas each at E9.5 (I) or three or four individual placentas of each genotype at E10.5 (J). *, values that differ from the respective WT placentas in a statistically significant manner (P < 0.05). Bars and error bars show mean values and SE.

To confirm the role of LCoR as a potential regulator of Muc1 in vivo, we generated Lcor-null mice from an embryonic stem (ES) cell clone (YHD419; International Gene Trap Consortium) carrying a lacZ splicing trap at the sixth intron of Lcor. Lcor-null embryos exhibited placental defects and fetal growth restriction (T. Shalom-Barak, J. Liersemann, and Y. Barak, unpublished data) but only died perinatally, allowing the collection of wild-type (WT), heterozygous, and homozygous Lcor-targeted placentas at various developmental stages. At E11.5, in situ hybridization (ISH) revealed abundant Lcor expression in all layers of the mouse placenta, including trophoblast giant cells, the spongiotrophoblast, and the labyrinth, but not in the maternal decidua (Fig. 2E), consistent with its previously reported expression in the human placenta (10). In Lcor-null placentas, Lcor expression was replaced faithfully by lacZ (Fig. 2F to H). Similar spatial expression patterns were observed at other stages of gestation (data not shown).

Next, we investigated the effects of LCoR deficiency on placental Muc1 expression at E9.5 (E0.5 designates noon of the day of copulation plug detection) and E10.5 (Fig. 2I and J), developmental stages at which Muc1 dependence on PPARγ is well established (7, 9). Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of Lcor with oligonucleotides positioned downstream from the gene trap insertion confirmed its expression in the placenta, its halving in Lcor+/− placentas, and its loss in Lcor-null placentas, validating transcriptional interference by the gene trap. Pparg expression was not significantly affected by the status of LCoR, whereas Muc1 expression decreased ∼2-fold in Lcor-null placentas at E9.5 and over 3-fold at E10.5 (P ≪ 0.05 in both), confirming that endogenous LCoR contributes significantly to its expression; Muc1 was not significantly altered in Lcor+/− placentas at either developmental stage. Combined, these analyses demonstrated the abundant expression of LCoR in the placenta and its importance for Muc1 transcription in the tissue.

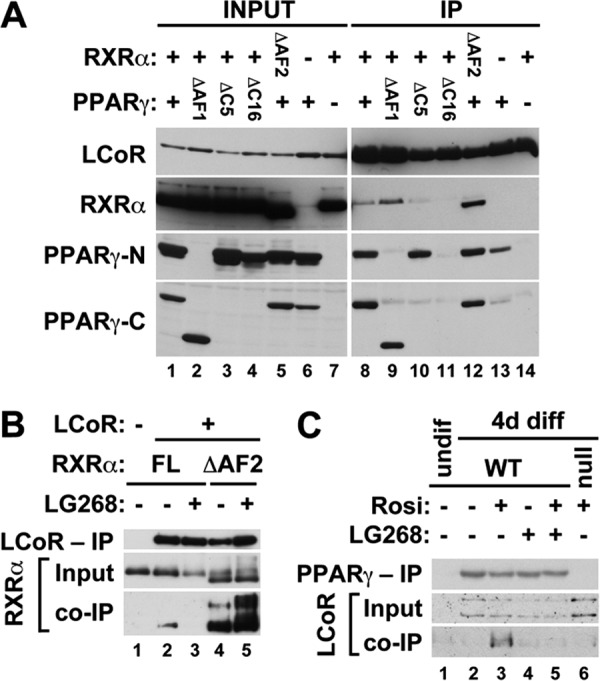

LCoR-PPARγ-RXRα interactions mirror the unique Muc1 activation configuration.

To further confirm and dissect the physical interactions of PPARγ and RXRα with LCoR, we next tested whether they are amenable to coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) from transfected cell extracts. As shown by the results in Fig. 3A, PPARγ and RXRα coimmunoprecipitated specifically with FLAG-LCoR when cotransfected into 293T cells. Co-IP from cells transfected with both PPARγ and RXRα was substantially more efficient than from cells transfected with each separately, indicative of synergy between both components of the heterodimer (Fig. 3A, lanes 8, 13, and 14). Heterodimers containing PPARγ-ΔC5 interacted with LCoR as robustly as heterodimers of full-length PPARγ (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 8 and 10), consistent with their transcriptionally active nature on Muc1, whereas the binding of heterodimers of the transcriptionally inactive PPARγ-ΔC16 was dramatically impaired (Fig. 3A, lane 11). Ancillary analysis of a PPARγ mutant lacking the N-terminal ligand-independent activation function 1 (AF1) domain demonstrated that this module did not contribute significantly to the interaction with LCoR (Fig. 3A, lane 9). Reassuringly, transcriptionally hyperactive heterodimers of RXRα-ΔAF2 bound LCoR much more strongly than native heterodimers (Fig. 3A, lane 12). Moreover, the interaction of monomeric full-length RXRα with cotransfected LCoR was weak in the presence of stripped, delipidated serum and was abolished when the cells were incubated with LG268 (Fig. 3B, lanes 2 and 3), whereas the interaction of RXRα-ΔAF2 monomers was dramatically stronger and refractory to the ligand (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 5).

FIG 3.

Effects of AF2 domain mutations and ligands on physical interactions of PPARγ and RXRα with LCoR. (A) Extracts of 293T cells cotransfected with N-terminally Flag-tagged LCoR and the indicated RXRα and/or PPARγ mutant combinations were resolved without IP (INPUT) or after IP with anti-Flag Ab beads (IP) and probed using Abs against Flag, RXRα, and the N or C terminus of PPARγ; the last two were used to detect PPARγ species lacking the opposite termini. (B) CV1 cells were grown in stripped serum and cotransfected with full-length (FL) RXRα alone (lane 1) or with Flag-LCoR and either FL-RXRα (lanes 2 and 3) or RXRα-ΔAF2 (lanes 4 and 5) in the absence (lanes 2 and 4) or presence (lanes 3 and 5) of LG268. Extracts were resolved without IP (Input) or after IP with anti-Flag Ab beads (top and bottom) and probed with anti-Flag (top) or anti-RXRα (middle, bottom) Abs. (C) TSC (gy11, WT, lanes 1 to 5, and gy9, Pparg null, lane 6) were cultured in the presence (lane 1) or absence (lanes 2 to 6) of fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4), heparin, and conditioned medium, along with combinations of Rosi and LG268, as indicated. After 4 days of differentiation, nuclear extracts were resolved without IP (Input, 5 μg) or after IP with anti-PPARγ Ab in the presence of the respective ligands (280 μg, top and bottom). Blots were probed with anti-PPARγ (top) or anti-LCoR (middle and bottom) Ab.

Most importantly, endogenous PPARγ and LCoR in TSC interacted in a manner that fully recapitulated the effects of ligands on Muc1 expression. As shown by the results in Fig. 3C, LCoR is not expressed in WT TSC prior to differentiation (Fig. 3C, lane 1), and two isoforms of approximately 53 kDa and 46 kDa are induced in cells that have differentiated for 4 days, irrespective of PPARγ and RXR ligands (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 and 5). Both isoforms are overexpressed in differentiated Pparg-null TSC (Fig. 3C, lane 6), consistent with previous microarray data (see the supplemental files in reference 7). Of all these combinations, only the larger LCoR isoform interacted with PPARγ in Rosi-treated WT TSC (Fig. 3C, lane 3), but it did not interact with PPARγ in untreated TSC (Fig. 3C, lane 2) or, more significantly, in TSC cotreated with Rosi and LG268 (Fig. 3C, lane 5).

Together, the full congruence of these binding profiles with the noncanonical effects of rexinoids and C-terminal mutations of PPARγ and RXRα on Muc1 promoter activation further supported the notion of LCoR as the cofactor behind these unique activation configurations. It further suggested that the basis for blunted Muc1 promoter activity in the presence of LG268 is ligand-mediated interruption of the interaction between RXRα and LCoR.

Novel, juxtaposed domains of LCoR mediate binding to PPARγ and RXRα.

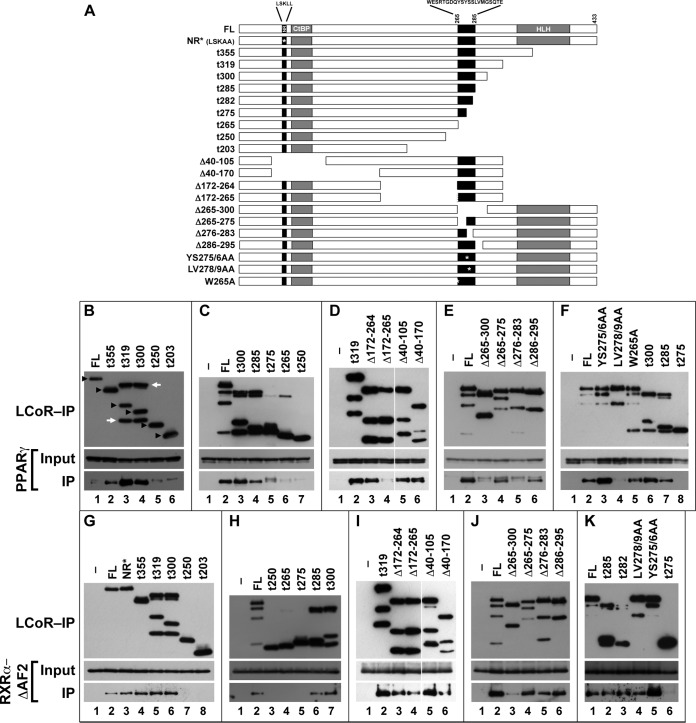

To map the PPARγ- and RXRα-binding domains of LCoR, we constructed a comprehensive series of C-terminal truncations, internal deletions, and point mutations of FLAG-LCoR (Fig. 4A) and analyzed their capacity to coimmunoprecipitate PPARγ and RXRα. Key data from these analyses are summarized in Fig. 4B to K. NR-binding LXXLL motifs typically interact with ligand-bound, intact AF2 domains (18, 19). The LSKLL sequence at aa 53 to 57 of LCoR is no exception, having been shown to mediate interactions with the estrogen and progesterone receptors (10). However, this module was dispensable for the interaction of LCoR with both PPARγ and RXRα (Fig. 4D, lanes 5 and 6, G, lane 3, and I, lanes 5 and 6). This is not surprising, considering that the Muc1-activating configuration of RXRα lacks the AF2 domain and that of PPARγ involves a partial, noncanonical AF2 domain structure.

FIG 4.

Mapping the PPARγ and RXRα interaction domains of LCoR. (A) Bar representation of the LCoR mutants used for the mapping. Locations of functional motifs are shown, including the canonical nuclear receptor box (NR), the tandem CtBP-binding motifs (CtBP), the putative helix-loop-helix sequence (HLH), and the deduced PPARγ- and RXRα-binding region (black box, aa 265 to 285). FL, full-length LCoR; NR*, NR box mutant; t355 to t203, mutants with truncation of all amino acids downstream from the indicated position. Internal deletions and point mutations are indicated. Amino acid sequences are spelled out in the corresponding locations of the NR and PPARγ/RXRα interaction boxes. (B to K) Extracts of 293T cells cotransfected with the indicated LCoR mutants along with either PPARγ (B to F) or RXRα-ΔAF2 (G to K) were resolved and blotted without IP (Input, middle) or after IP with anti-Flag Ab beads (top and bottom). Blots were probed with anti-Flag Ab (top), anti-PPARγ Ab (B to F, middle and bottom), or anti-RXRα Ab (G to K, middle and bottom). (B) Black arrowheads identify the presumptive unprocessed LCoR species translated from the respective constructs, a rightward white arrow points to the ∼270-aa-long cleavage products of LCoR-t319 and LCoR-t300, and a leftward white arrow points to its ∼380-aa-long deduced conjugate. Identically processed species or, where applicable, their internally deleted versions can be observed in the remaining panels, most robustly with C-terminal truncations of LCoR between aa 282 and 319. Additional LCoR breakdown products of other sizes appear in various extracts sporadically but inconsistently.

C-terminal truncations of LCoR downstream from aa 282, as well as in-frame deletions ranging from aa 40 to aa 264, had no effect on its binding to PPARγ (Fig. 4B, lanes 2 to 4, C, lanes 3 and 4, D, lanes 3, 5, and 6, and F, lanes 6 and 7). In contrast, C-terminal truncations starting at or upstream from aa 275 interfered with PPARγ binding (Fig. 4B, lanes 5 and 6, C, lanes 5 to 7, and F, lane 8). Moreover, in-frame deletions of aa 265 to 300 and aa 276 to 283, but not of aa 265 to 275 or aa 286 to 295, abolished interaction with PPARγ (Fig. 4E, lanes 3 to 6). Most critically, the differential PPARγ binding of two point mutants within the aa-276-to-282 minimal interaction box, with the mutations YS275/6AA and LV278/9AA, ruled out S276 while pinpointing L278 and/or V279 as core residues of the binding motif (Fig. 4F, lanes 3 and 4). In aggregate, these data narrowed the PPARγ-interacting motif of LCoR to the SLVMGS sequence from aa 277 to 282, of which at least the L and/or V are essential. Interestingly, two closely related in-frame deletion mutations of LCoR, spanning aa 172 to 264 and aa 172 to 265 (LCoR-Δ172–264 and LCoR-Δ172–265), bound PPARγ differentially, the former reproducibly interacting with and the latter consistently failing to coimmunoprecipitate PPARγ (Fig. 4D, lanes 3 and 4). However, additional mutations involving aa 265, including the deletion of aa 265 to 275 (Fig. 4E, lane 4) or its mutation from tryptophan to alanine (W265A) (Fig. 4F, lane 5), indicated that it is not part of a primary binding sequence but may instead affect the conformation or accessibility of the binding module.

To map the RXRα-binding domain of LCoR, we used RXRα-ΔAF2, whose stronger interaction with LCoR compared to that of the full-length receptor is conducive to more robust analysis. Similar to the results for PPARγ, mutants with C-terminal truncations of LCoR up to aa 282, as well as internal deletions between aa 40 and aa 264, were compatible with uninterrupted binding of RXRα-ΔAF2 (Fig. 4G, lanes 4 to 6, H, lanes 6 and 7, I, lanes 3 to 6, and K, lanes 2 and 3). Further similarity to the results for PPARγ was found in the abolished interaction of LCoR species truncated at or upstream from aa 275 (Fig. 4G, lanes 7 and 8, H, lanes 3 to 5, and K, lane 6) or lacking the entire block between aa 265 and 300 (Fig. 4J, lane 3). However, unlike PPARγ, RXRα-ΔAF2 interacted potently with LCoR-Δ172–265, revealing the first of several divergent binding specificities between the two receptors (Fig. 4I, lane 4, versus D, lane 4). Moreover, all of the mutants with subdeletions in the region from aa 265 to 300, including the mutant with the non-PPARγ-binding deletion of aa 275 to 283, retained substantial RXRα-ΔAF2 binding (Fig. 4J, lane 4 to 6). As importantly, LCoR-LV278/9AA, which altogether failed to bind PPARγ, retained uninterrupted binding to RXRα-ΔAF2 (Fig. 4K, lane 4). Together, these data demonstrated that the RXRα interaction module lies within 10 to 20 aa of the PPARγ-binding motif, but the two are clearly distinct. Moreover, LCoR can bind RXRα via at least two primary motifs between aa 265 and 300, each singularly sufficient to support the interaction. This conclusion is consistent with the synergistic binding of PPARγ-RXRα heterodimers to LCoR compared to the binding of each receptor alone.

On a minor note, these analyses revealed that transfected LCoR undergoes two specific modifications: first, cleavage around aa 275 to 280, and then, conjugation of the N-terminal cleavage product to an ∼10- to 12-kDa moiety that we have not identified. These are manifested as Flag-reactive bands of approximately 30 kDa and 40 to 42 kDa, respectively (annotated in Fig. 4B), and are enhanced in C-terminally truncated species. It is currently unclear whether these modifications are artifacts or physiologically significant. However, concerns of functional relationships with the juxtaposed PPARγ/RXRα-binding domains are assuaged by the productive binding of both PPARγ and RXRα to LCoR-Δ286–295, which has no discernible cleavage or conjugation products (Fig. 4E, lane 6, and J, lane 6).

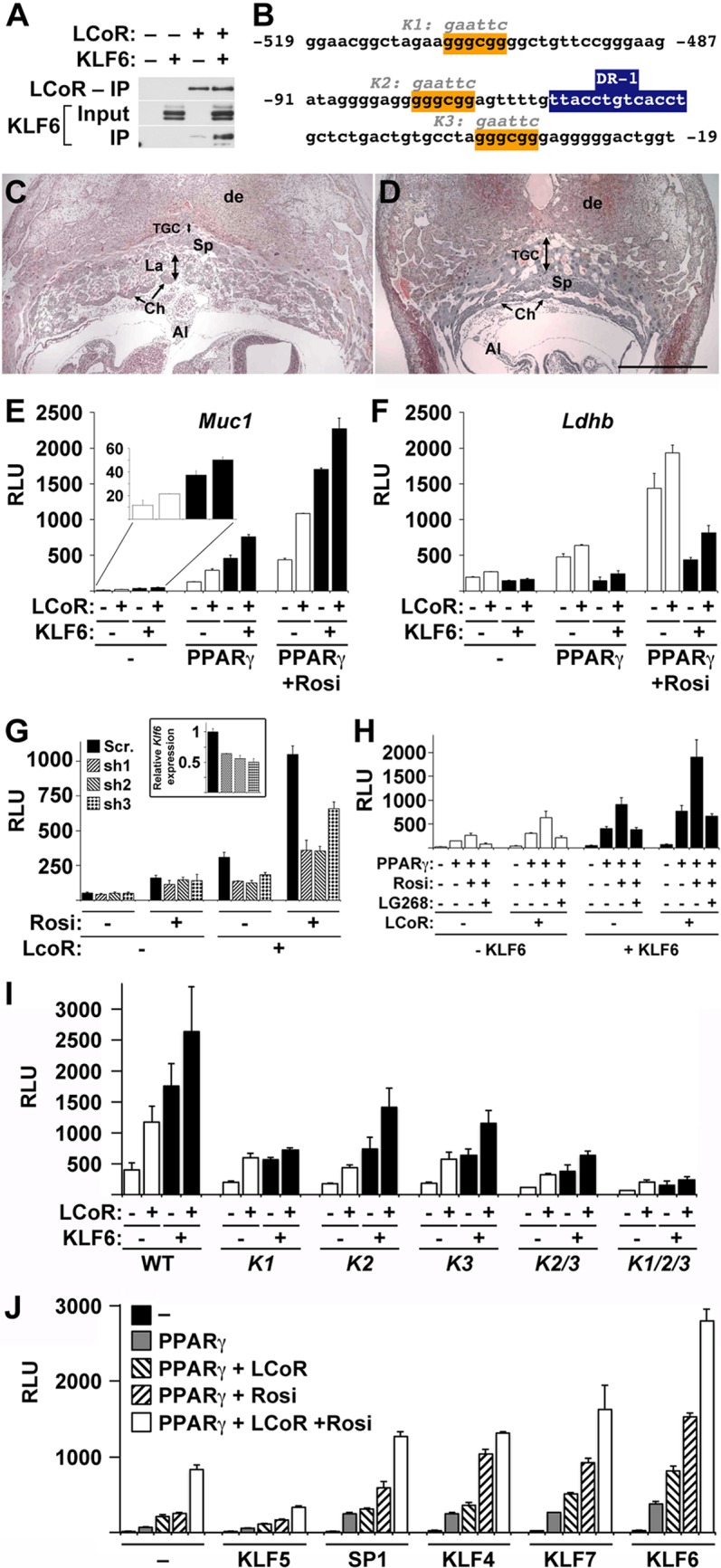

KLF6 cooperates with PPARγ and LCoR in Muc1 activation.

LCoR was previously shown to interact with and act as a specific corepressor of the Kruppel-like family transcription factor KLF6 (11). The results shown in Fig. 5A confirm the robustness and specificity of these interactions via co-IP of both proteins from cotransfected 293T cells. Importantly, the minimal PPARγ-responsive fragments of the Muc1 promoter contain three putative GGCG KLF-binding motifs (20), one within the non-PPARγ-binding distal enhancer and two flanking the PPRE in the proximal promoter region (Fig. 5B). Moreover, KLF6 is enriched in the placenta (21), and its deletion in mice leads to early fetal death, which was reported to stem from hematopoietic defects but whose general phenotypic characteristics are equally consistent with placental defects (22). Indeed, histological analysis of Klf6-null placentas at E9.5 reveals trophoblast giant cell overexpansion and complete lack of fetal vessel permeation and labyrinth formation, establishing a compelling alternative explanation for the embryonic lethality (Fig. 5C and D). This “guilt by association” whereby KLF6 is expressed in the placenta, is essential for its development at the same stage as PPARγ, and engages LCoR prompted us to evaluate functional interaction between PPARγ, LCoR, and KLF6 in Muc1 regulation.

FIG 5.

KLF6 regulates placental development and cooperates with PPARγ, RXRα, and LCoR in Muc1 induction. (A) Extracts of 293T cells cotransfected with the indicated combinations of Flag-LCoR and KLF6 were resolved without IP (Input, middle) or after IP with anti-Flag Ab beads (top, bottom) and probed using Abs against Flag (top) or KLF6 (middle, bottom). (B) Putative SP1/KLF-binding sites (orange boxes) within the minimal PPARγ-responsive sequences of the Muc1 promoter. Sequences designated K1, K2, and K3 delineate the alterations of the three mutant KLF/SP motifs analyzed in the experiments whose results are shown in panel H. The blue box marks the previously determined proximal PPRE (9). (C and D) Midsections of WT (C) and Klf6-null placentas at E9.5 (D) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Both WT and Klf6-null placentas have undergone allantoic (Al) fusion, but the Klf-null placenta is completely devoid of the vascular labyrinth (La in panel C; none in panel D) and exhibits aberrant expansion of the spongiotrophoblast (Sp) and, particularly, the trophoblast giant cell (TGC) layer. Ch, chorion; de, decidua. (E, F) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL and RXRα (all), as well as PPARγ, LCoR, and/or KLF6 where indicated, and treated with 1 μM Rosi as marked, along with either Muc1-luc (E) or Ldhb-luc (F). (G) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, Muc1-luc, RXRα and PPARγ (all), with or without LCoR, as labeled, in the presence or absence of 1 μM Rosi, as marked, and a plasmid expressing the indicated control, scramble shRNA (Scr). or one of three CV1 Klf6-specific shRNA molecules. Inset, RT-qPCR analysis of endogenous Klf6 in CV1 cells transfected with a GFP-expressing vector along with a control or Klf6-specific shRNA construct, as indicated, and enriched to approximately 50 to 60% via 8 days of selection with puromycin. (H) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, Muc1-luc, and RXRα (all), as well as PPARγ and/or LCoR, as labeled, and treated with 1 μM Rosi, alone or with 1 μM LG268, as marked, in the absence or presence of KLF6. (I) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, RXRα, and PPARγ and treated with 1 μM Rosi (all), as well as LCoR and/or KLF6, as labeled, and Muc1 promoter variants carrying the indicated single and combined KLF/SP motif mutations. (J) Normalized RLU in CV1 cells transfected with pCMX-βGAL, Muc1-luc, and RXRα (all), as well as PPARγ and/or LCoR, as labeled, with or without 1 μM Rosi, as marked, and the indicated members of the SP/KLF family. Bars and error bars show mean values and SE.

As hypothesized, KLF6 activated the Muc1 promoter in a robust, strictly PPARγ-dependent fashion that is further augmented by LCoR (Fig. 5E). The effect of KLF6 on Muc1 in the absence of PPARγ was minimal, amounting to only 3 to 5% of the levels in the presence of PPARγ, with or without Rosi or LCoR (Fig. 5E, inset). This effect was specific to Muc1; KLF6 inhibited the Ldhb promoter (Fig. 5F), suggesting that its PPARγ-dependent activity on Muc1 is not the generic action of a basal SP1 family transcription factor. Moreover, knockdown of endogenous Klf6 in the host CV1 cells significantly blunted Muc1 promoter activation by PPARγ, RXRα, and LCoR, both with and without Rosi (Fig. 5G, right). Interestingly, this knockdown had no measurable effect on Muc1 activation in the absence of LCoR (Fig. 5G, left), raising the possibility that the primary contribution of KLF6 to Muc1 activation is be by synergizing with LCoR on the promoter complex. Like LCoR, KLF6 did not fundamentally alter the effect of LG268 on the Muc1 promoter but augmented reporter activity proportionately with all combinations of PPARγ, LCoR, Rosi, and LG268 tested (Fig. 5H).

To test which of the three putative KLF/SP motifs in the PPARγ-responsive modules of the Muc1 promoter might mediate the transcriptional effect of KLF6, we analyzed mutations in each of these elements, alone and together (Fig. 5B). As shown by the results in Fig. 5I, all mutations affected the response of the Muc1 promoter to LCoR and KLF6 when RXRα, PPARγ, and Rosi were present. However, while mutations of the two proximal motifs, designated K2 and K3, alone or combined, dampened the response generically across all KLF6 and LCoR combinations, a mutation of the distal motif, designated K1, blunted the cooperativity between KLF6 and LCoR; either factor individually enhanced the response to PPARγ, but the two no longer synergized. A triply mutated promoter exhibited an extremely dampened response that was also refractory to LCoR-KLF6 synergy. These data further support the notion of functional synergy between KLF6 and LCoR on the Muc1 promoter.

Lastly, considering the overlapping DNA recognition specificities of KLF/SP1 family members (20), we assessed the effect of KLF6 on Muc1 compared to those of the closely related KLF5, SP1, KLF4, and KLF7. The results in Fig. 5J show that KLF5 inhibited Muc1 activation by any PPARγ and LCoR combination, whereas SP1, KLF4, and KLF7 activated Muc1 comparably to KLF6 in the presence of PPARγ, with or without Rosi. However, none of the three augmented the effect of LCoR as robustly as KLF6, suggesting that all four may cooperate interchangeably with PPARγ and RXRα on Muc1, whereas KLF6 was the most synergistic with LCoR.

Together, these data suggest that KLF6 is an essential placental transcription factor that cooperates with PPARγ, RXRα, and LCoR in Muc1 activation, primarily via a GGCG motif in the upstream Muc1 enhancer.

DISCUSSION

RXRs as modulators of NR signaling—significance and implications.

This study amends the prevailing paradigm of RXRs as coreceptors that either passively support or augment the activity directed by their heterodimeric partners (17, 23, 24). Our data show that RXRs can also counteract the activity of their partner and, thus, are dynamic modulators of NR signaling in their own right. In the whole organism, such a mechanism could integrate local or systemic inputs to fine-tune developmental or physiological outcomes by suppressing specific targets of heterodimeric NR, Muc1 being the first example. Such targets might be required in some scenarios but harmful in others, in which they must be silenced. The physiological contexts and differential outcomes, as well as which targets are subject to such dual regulation, remain to be elucidated.

This expanded repertoire of RXR activity may open the door to novel approaches for modulating the pharmacological effects of insulin-sensitizing TZDs, which often cause severe, even fatal side effects (25–29). Moreover, if rexinoid-mediated inhibition is part of the response spectrum of other heterodimeric NRs, combination rexinoid therapy may be applicable to compounds as diverse as retinoids, vitamin D, thyroid hormone, or xenobiotics. At this stage, this is a long shot that hinges on identifying and sorting heterodimeric receptor targets in various tissues into rexinoid-suppressed, rexinoid-neutral, and rexinoid-stimulated clusters and assessing the potential beneficial versus harmful physiological impact of each such cluster as a whole. At least in the narrow context of Muc1, which is implicated as an oncogene in various epithelial and lymphatic malignancies (30, 31), it is tempting to assume that such rexinoid-mediated suppression might be beneficial in certain circumstances.

Interestingly, unlike the septal defects and midgestation lethality of Rxra-null embryos, mouse embryos lacking just the AF2 domain of the receptor do not exhibit cardiac malseptation and die at term (32–35). However, these embryos still exhibit some of the placental defects typical of complete RXRα deficiency (33). These phenotypic differences indicate that the AF2 domain is indispensable for some functions of RXRα in the placenta and in late gestation but is dispensable for others, including Muc1 expression, the development of the ventricular septum, and midgestation survival.

LCoR, a novel type of PPARγ-RXRα coactivator.

LCoR initially drew our attention as a candidate rexinoid-suppressed cofactor due to its contrarian mode of action—a corepressor recruited by NR agonists (10, 36). Curiously, it fit the bill with two unexpected twists. First, it functioned as a Muc1 coactivator, rather than corepressor, with all ligand combinations. This was surprising in light of its strong association with C-terminal binding proteins 1 and 2 (CtBP1 and -2) and histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) (10, 36). However, recent data indicate that CtBP2 can coactivate in certain contexts, in addition to its established corepressor functions (37), and that LCoR coactivates some estrogen-induced genes (38). Our data further showcase this flexibility of LCoR as a transcriptional corepressor or coactivator depending on the context. The second surprise was that the rexinoid-bound conformation of RXRα-AF2 suppressed Muc1 activation by interfering with the ability of LCoR to bind PPARγ-RXRα heterodimers. This phenomenon is reminiscent of the interactions of NRs with canonical corepressors, in which the binding surface of the receptor is fully accessible in the ligand-free conformation but is masked by the AF2 domain in the presence of ligand (39); the distinctions are that here, this mechanism modulates coactivation, not corepression, and that the RXR interaction region of LCoR contains no identifiable CoRNR motif (40). It is tempting to speculate that LCoR may not be the only cofactor with these NR-binding characteristics and that similar properties of other cofactors perhaps eluded detection previously because they were not analyzed for rexinoid response.

Several criteria strongly implicate LCoR as the key cofactor of PPARγ and RXRα on the Muc1 promoter in the placenta. (i) The effect of LCoR on Muc1 in heterologous reporter assays was entirely PPARγ and RXRα dependent and the strongest of any cofactor tested. (ii) LCoR was highly selective toward Muc1 and had no effect on a canonical 3xDR1 reporter or on the Ldhb promoter, arguing against promiscuous activity. (iii) The unique activity patterns of PPARγ and RXRα AF2 domain mutants on Muc1 were fully consistent with their physical interactions with LCoR: all nonstandard mutant configurations that activated Muc1 bound LCoR, whereas those that failed to activate Muc1 did not bind LCoR. (iv) Most importantly, LCoR is highly enriched in the placenta, and its deficiency more than halved Muc1 expression in the tissue, unequivocally demonstrating that it participates in Muc1 regulation in vivo.

The discrepancy between the ∼15-fold plunge in Muc1 expression in Pparg-null placentas (7) and its more modest 2- to 3-fold drop in Lcor-null ones has two plausible explanations. First, it is possible that other cofactors substitute for LCoR on the Muc1 promoter, partially compensating for its deficiency. Second, as we have shown before, PPARγ plays a dual role on the Muc1 promoter, both to derepress a proximal PPRE to unleash induction by a strong, more distal non-PPARγ-binding enhancer and then to activate transcription in its own right (9). LCoR likely plays a prominent role in transcription activation by PPARγ but might be partly or fully dispensable for displacement of the basal PPRE-bound repressor, which accounts for a large share of PPARγ's contribution. Consistent with this interpretation, rexinoids abolish Rosi-mediated transactivation but have a more subtle effect on the response of Muc1 to unliganded PPARγ, which presumably accounts for the derepression component.

Importantly, the NR-binding motifs of LCoR are novel. The sequence SLVMGS at positions 277 to 282, of which at least the L and/or V residues are indispensable, is identified here as a motif that binds a noncanonical configuration of the PPARγ AF2 domain. In addition, two other modules between aa 265 and 300, which currently have eluded identification but are distinct from the PPARγ-binding module, can each interact with non-AF2 residues of RXRα. This interaction pattern explains the synergistic binding of the two receptors to LCoR and is consistent with the different Muc1-activating configurations of each.

KLF6, the placenta, and RXRα-PPARγ-LCoR complexes.

We show here that KLF6 is critical for placental development and contributes to Muc1 activation. The severely dysmorphic and completely avascular Klf6-null placental phenotype cannot be compatible with embryonic survival, as seen in scores of other mutants, suggesting that the previous attribution of the cause of death to hematopoietic defects may have been in error (22). In fact, the hematopoietic abnormalities in Klf6-null embryos may well be secondary to the placental defects, considering the recent identification of the placenta as the prehepatic hematopoietic stem cell niche (41, 42).

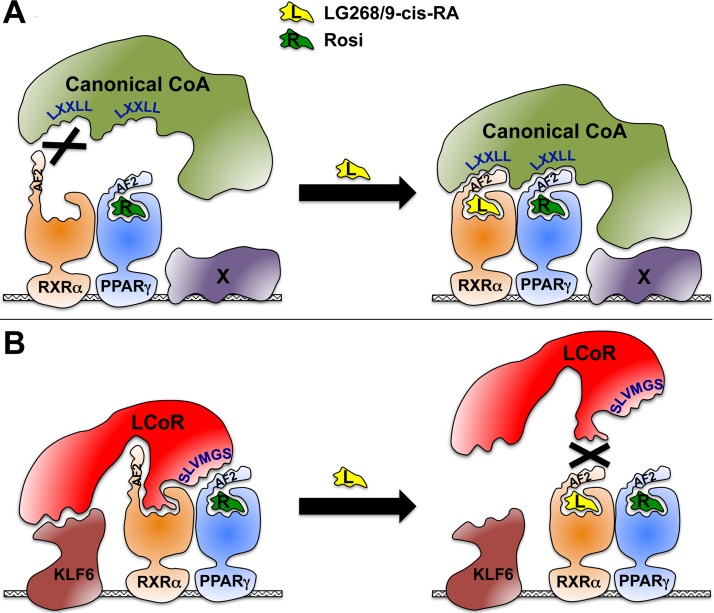

KLF6 augments Muc1 activation by PPARγ, RXRα, and LCoR twice as robustly as other SP/KLF family members tested. This specificity is significant, considering the largely simplistic core sequence of SP/KLF response elements and their ill-defined relationships to their cognate factors, as well as the demonstrated physical interaction of KLF6 with LCoR, as shown both previously (11) and here. We find here that of the three putative GGCG SP/KLF recognition motifs within the core PPARγ-responsive modules of the Muc1 promoter, the one within the upstream enhancer is crucial for the cooperativity between KLF6 and LCoR. Moreover, knockdown of endogenous KLF6 fleshes out its importance for the ability of LCoR to coactivate PPARγ and RXRα on the Muc1 promoter. These data suggest that KLF6 is a key, specific link in a daisy chain of interactions that synergize to cement the transcriptional complex on the Muc1 promoter. Figure 6 is a graphic interpretation of our findings, incorporating this daisy chain concept into a comparison of the interactions of PPARγ-RXRα heterodimers with canonical coactivators (Fig. 6A) to their interaction with LCoR and KLF6 (Fig. 6B). We postulate that PPARγ-RXRα heterodimers docked to a PPRE engage coactivators depending on the ligand milieu; i.e., the availability of PPARγ ligands and rexinoids. Canonical coactivators utilize LXXLL motifs to engage the intact AF2 domains of both liganded PPARγ and RXRα. Rexinoids unleash the full activity of such coactivators by promoting their synergistic binding to both receptors. In contrast, LCoR uses two distinct non-LXXLL motifs, one to interact with the N-terminal part of the PPARγ AF2 and the other with a surface of RXRα that is accessible only in its ligand-free conformation. Here, rexinoids disrupt synergy by promoting a conformation that interrupts LCoR-RXRα interaction. In our model, coactivator choice is further facilitated through tethering to target-specific transcription factors (Fig. 6A, X, and B, KLF6). In the case of the Muc1 promoter, KLF6 appears to fulfill this role, thanks to its functional interaction with the upstream GGCG element on one hand and with LCoR on the other hand. In this manner, the eight components—the proximal PPRE, PPARγ, RXRα, PPARγ ligand, the obligatory absence of rexinoids, LCoR, KLF6, and the upstream SP/KLF response element—form a highly cooperative, stable interaction loop on the Muc1 promoter. This model is likely a simplification of the full picture, considering that we have not yet identified some of the factors that bind other key elements in the Muc1 promoter and which may further modulate this synergy.

FIG 6.

Model of LCoR as a rexinoid-inhibited PPARγ/RXRα coactivator. A schematic comparison of rexinoid effects on the interactions of PPARγ/RXRα-occupied promoter complexes with canonical coactivators (A) versus LCoR (B). See Discussion for details.

In summary, prompted by unusual properties of PPARγ and RXRα and their ligands on the Muc1 promoter, we report here multiple discoveries impinging on trophoblast transcriptional networks, placental development, PPARγ and NR signaling in general, and cofactor-NR interactions. This study showcases the value of analyzing complex, real-life target promoters for illuminating novel mechanistic principles as an independent complement to studies of the physiological function of the target gene product itself.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and chemicals.

The plasmids pCMX-Pparg, pCMX-Rxra, pCMX-lacZ, 3xDR1-luc, Muc1(−715)-luc (abbreviated as Muc1-luc), and Ldhb(2.7Kb)-luc were previously described (7, 9). So were pCMX-Rxra-ΔAF2, and pCMX-Pparg-L466/7A (16, 17). pCMX-Pparg-ΔC16 and pCMX-Pparg-ΔC5 were derived by standard recombinant DNA technology from pCMX-Pparg. pCMX-Lcor (human) was constructed by subcloning the insert from plasmid number MHS1010-9205527 (Open Biosystems/Dharmacon) into pCMX. pCMX-Flag-Lcor (human) was subcloned from the previously described pCDNA-Flag-Lcor (10). This plasmid served as the template for truncation, deletion, and point mutations via standard recombinant DNA technology and PCR-mediated mutagenesis, as appropriate. Expression plasmids for KLF family members were purchased from Open Biosystems/Dharmacon; they included pCMV-SPORT6-KLF6 (mouse; catalog number MMM1013-65920), pCMV-SPORT6-SP1 (human, catalog number MHS1010-7429705), pCMV-SPORT6-KLF4 (mouse; catalog number MMM1013-64603), pCMV-SPORT6-KLF5 (mouse; catalog number MMM1013-64973), and pCMV-SPORT6-KLF7 (mouse; catalog number MMM1013-63374). All acquired plasmids were verified by end sequencing, and all fragments derived by PCR for the experiments described herein were fully sequenced both to validate the desired mutation and ensure the absence of PCR-generated errors elsewhere. Rosi was purchased from Cayman Chemicals and 9-cis-RA from Sigma-Aldrich; the synthetic rexinoids LG268 and LG754 were a kind gift from Ligand Pharmaceuticals.

Cells, transfections, and reporter assays.

CV1 cells were cultured, transfected, and assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase in a 48-well format as described previously (7, 9). Importantly, the cells were perpetually passaged in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% double-stripped newborn calf serum (ds-NCS), and transfected cultures incubated with DMEM containing 2% superstripped fetal bovine serum (ss-FBS); maintenance in nonstripped NCS or culturing posttransfection in higher concentrations of ss-FBS almost completely abolished induction by Rosi, likely due to the presence of putative trace rexinoids, as suggested by the refractoriness of RXRα-ΔAF2 to this effect. ds-NCS was prepared by heat inactivation (1 h, 55°C), 5 h of incubation at room temperature with 5% (wt/vol) AG 1-X8 resin (Bio-Rad), overnight incubation at 4°C with 5% AG 1-X8 resin and 2% (vol/vol) charcoal-dextran solution (5% Norit A [Serva], 5% charcoal [Serva], 0.5% dextran 70 [GE Healthcare Life Sciences]), 1 h of incubation at 55°C with 2% charcoal-dextran, centrifugation, and filtration. Heat-inactivated ss-FBS was prepared by tandem overnight incubations at room temperature with 2% (wt/vol) charcoal and 5% AG 1-X8 resin, centrifugation, and filtration. The TSC lines GFP-Trf, gy11, and gy9 (7, 43) were cultured and treated as previously described (7, 9); these cells were intolerant to stripped sera but fortuitously supported a substantial response of endogenous Muc1 to Rosi in the presence of 20% nonstripped FBS while still allowing a strong inhibitory effect of 1 μM LG268; the basis for this difference from CV1 cells is currently unknown. 293T cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and transfected with DOTAP (1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium propane; Avanti Polar Lipids). As stripped serum was also incompatible with the wellbeing of these cells, the effect of LG268 on co-IP of LCoR and RXRα was tested in CV1 cells.

To knock down endogenous KLF6 in CV1 cells, the following three small hairpin RNA (shRNA) configurations were designed based on Klf6 of Chlorocebus sabaeus, the closest sequenced relative of Chlorocebus aethiops, from which CV1 cells were originally derived: sh1, AAGGAGGAATCCGAACTGAAG; sh2, AATCCGAACTGAAGATATCTT; and sh3, AACGGCTGCAGGAAAGTTTAC. A random sequence, TCCTAAGGTTAAGTCGCCCTCG, was used as a negative control (scramble). Oligonucleotides containing hairpin configurations of all sequences were cloned into the plasmid pLKO.1-puro (Addgene plasmid number 8453) (44). In reporter assays, each of the constructs was added to the transfection cocktails in a quantity similar to that of the expression plasmids. Klf6 knockdown efficiency was measured by transfecting each of the shRNA constructs into CV1 cultures together with the plasmid pLKO5.sgRNA.EFS.GFP (Addgene plasmid number 57822) (45), using polyethylenimine (PEI) as described previously (46). After subsequent selection at escalating puromycin concentrations from 15 to 24 μg/ml for 8 days, approximately 50 to 60% of the surviving cells were green fluorescent protein (GFP) positive, at which point RNA was extracted and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) of C. sabaeus Klf6 performed as described below.

Co-IP, Western blotting, and antibodies.

293T or CV1 cells were cotransfected with the indicated vector combinations in 60-mm dishes, extracted 48 h later in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA, 25 μg/ml aprotinin and leupeptin, 1.25 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]), and cleared by centrifugation. Approximately one-third of each lysate was precleared with 20 μl Sepharose beads for 1 h at 4°C and then immunoprecipitated for 1 h at 4°C with 20 μl anti-FLAG Ig M2 affinity gel (A2220; Sigma-Aldrich). The beads were washed once in lysis buffer, three times in lysis buffer containing 0.5 M NaCl, and once more in lysis buffer. Precipitates were dissociated from the gel by boiling in 2× Laemmli sample buffer without β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), to minimize release of the M2 antibody. The supernatants were carefully separated from the beads by iterative centrifugation, supplemented with 4× Laemmli buffer containing β-ME, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blotted onto nitrocellulose filters.

For co-IP of endogenous proteins, nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously (9) from undifferentiated or differentiated cultures of the TSC lines gy9 and gy11 (7) grown in the absence or in the presence of the respective ligand combinations. IP was carried out as described above, except that protein A beads and anti-PPARγ Ab (47) were used, and the respective ligands were added to the reaction mixtures during all of the precipitation and wash steps.

The primary antibodies (Abs) used for Western blotting included a custom-made rabbit polyclonal Ab (PAb) against the N-terminal 120 aa of PPARγ (PPARγ-N) (47), a rabbit monoclonal antibody (MAb) against the C terminus of PPARγ (PPARγ-C) (81B8; Cell Signaling Technology), a rabbit anti-RXRα MAb (ab125001; Abcam), a rabbit anti-Flag PAb (catalog number 2368; Cell Signaling Technology), a mouse anti-LCoR MAb (C6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and a rabbit anti-KLF6 PAb (R-173; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary Abs used included the following: with PPARγ-N, RXRα, Flag, and KLF6 Abs, mouse anti-rabbit IgG, light chain-specific MAb (catalog number 211-032-171; Jackson ImmunoResearch); with anti-LCoR Ab (C6), mouse IgGκ binding protein-HRP (catalog number sc-516102; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); and with PPARγ-C MAb (81B8), which is not recognized by the light chain-specific Ab, affinity purified goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) (catalog number 111-005-144; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Enhanced chemiluminescence was performed using SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Pierce).

Mice.

Mice carrying a disrupted Lcor allele were derived from an Lcor-targeted embryonic stem (ES) cell clone, YHD419, procured from the International Gene Trap Consortium. The β-geo splicing trap in YHD419 is localized to the sixth intron of Lcor, resulting in an allele that cannot express the bulk of the coding sequence (the 323 C-terminal aa of the 433-aa-long LCoR). Heterozygous Lcor+/− congenic sublines, Lcs and Lcb, were developed by introgressing YHD419 chimeras onto either a 129S1/SvImJ (129) or a C57BL/6J (B6) background, respectively. All placentas analyzed were from hybrid progeny of Lcs sires with Lcb dams, at the fourth backcross (N4) or higher, in order to minimize undesirable genetic background effects. Mice and embryos were genotyped using the following oligonucleotides: common, TTGGTGGTGTCTTAGGGAAAGACTGTT, WT, GTCAACAGAAGAGGCAGCTAGGAGG, and null (lacZ), GCTGGCGAAAGGGGGATGTGCTGCAAG, yielding products of ∼250 bp (WT) and ∼320 bp (null allele). All mouse studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Pittsburgh and Magee-Womens Research Institute.

Expression analyses.

RNA extraction from TSC or whole placentas, Northern blotting, RT-qPCR, and ISH were performed as previously described (7). Oligonucleotide pairs used for RT-qPCR measurements of Pparg, Muc1, and 36B4 were described previously (7). RT-qPCR analysis of mouse Lcor used the following oligonucleotide pair from the eighth exon, not expressed by the null allele: forward, TGAACAAGACGGTGTACTTGAC, and reverse, GAACTTTGAGTGATGTGGAGTGT. Oligonucleotide sequences for RT-qPCR analyses of RNA from CV1 cells were as follows: Klf6, forward, CTTCCAGGAGCTCCAGATCGTGC, and reverse, GGCTCACTCTGGAGGTAACGTT; 36B4, forward, AGATCAGGGACATGTTGCTGGC, and reverse, TCGGGCCCAAGTCCAGTGTTC. The antisense lacZ riboprobe for ISH was described previously (5). The Lcor ISH riboprobe was restricted to exons 7 and 8, which are not expressed by the null allele.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was supported by NIH grants number R01HD044103 and number P01HD069316, Pennsylvania Department of Health Research Formula Funds, MWRI startup funds to Y.B., and NIH grant number R01DK56621 to S.L.F.

We thank Frances Lutka for assistance with mouse breeding and genotyping and Bruce Campbell for editorial assistance.

We all declare no conflicts of interest related to the reported study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Noonan DJ, Heyman RA, Evans RM. 1992. Convergence of 9-cis retinoic acid and peroxisome proliferator signalling pathways through heterodimer formation of their receptors. Nature 358:771–774. doi: 10.1038/358771a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman BM, Tontonoz P, Chen J, Brun RP, Spiegelman BM, Evans RM. 1995. 15-Deoxy-δ 12,14-prostaglandin J2 is a ligand for the adipocyte determination factor PPARγ. Cell 83:803–812. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. 1995. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma). J Biol Chem 270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. 1994. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 79:1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. 1999. PPARγ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell 4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sapin V, Dolle P, Hindelang C, Kastner P, Chambon P. 1997. Defects of the chorioallantoic placenta in mouse RXRα null fetuses. Dev Biol 191:29–41. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shalom-Barak T, Zhang X, Chu T, Schaiff WT, Reddy JK, Xu J, Sadovsky Y, Barak Y. 2012. Placental PPARγ regulates spatiotemporally diverse genes and a unique metabolic network. Dev Biol 372:143–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guttmacher AE, Maddox YT, Spong CY. 2014. The Human Placenta Project: placental structure, development, and function in real time. Placenta 35:303–304. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shalom-Barak T, Nicholas JM, Wang Y, Zhang X, Ong ES, Young TH, Gendler SJ, Evans RM, Barak Y. 2004. PPARγ controls Muc1 transcription in trophoblasts. Mol Cell Biol 24:10661–10669. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10661-10669.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes I, Bastien Y, Wai T, Nygard K, Lin R, Cormier O, Lee HS, Eng Bertos FNR, Pelletier N, Mader S, Han VK, Yang XJ, White JH. 2003. Ligand-dependent nuclear receptor corepressor LCoR functions by histone deacetylase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Mol Cell 11:139–150. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calderon MR, Verway M, An BS, DiFeo A, Bismar TA, Ann DK, Martignetti JA, Shalom-Barak T, White JH. 2012. Ligand-dependent corepressor (LCoR) recruitment by Kruppel-like factor 6 (KLF6) regulates expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1A gene. J Biol Chem 287:8662–8674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.311605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee R, Davies PJ, Crombie DL, Bischoff ED, Cesario RM, Jow L, Hamann LG, Boehm MF, Mondon CE, Nadzan AM, Paterniti JR Jr, Heyman RA. 1997. Sensitization of diabetic and obese mice to insulin by retinoid X receptor agonists. Nature 386:407–410. doi: 10.1038/386407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lala DS, Mukherjee R, Schulman IG, Koch SS, Dardashti LJ, Nadzan AM, Croston GE, Evans RM, Heyman RA. 1996. Activation of specific RXR heterodimers by an antagonist of RXR homodimers. Nature 383:450–453. doi: 10.1038/383450a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Danielian PS, White R, Lees JA, Parker MG. 1992. Identification of a conserved region required for hormone dependent transcriptional activation by steroid hormone receptors. EMBO J 11:1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leng X, Blanco J, Tsai SY, Ozato K, O'Malley BW, Tsai MJ. 1995. Mouse retinoid X receptor contains a separable ligand-binding and transactivation domain in its E region. Mol Cell Biol 15:255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulman IG, Juguilon H, Evans RM. 1996. Activation and repression by nuclear hormone receptors: hormone modulates an equilibrium between active and repressive states. Mol Cell Biol 16:3807–3813. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.7.3807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schulman IG, Shao G, Heyman RA. 1998. Transactivation by retinoid X receptor-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) heterodimers: intermolecular synergy requires only the PPARγ hormone-dependent activation function. Mol Cell Biol 18:3483–3494. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.6.3483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torchia J, Rose DW, Inostroza J, Kamei Y, Westin S, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. 1997. The transcriptional co-activator p/CIP binds CBP and mediates nuclear-receptor function. Nature 387:677–684. doi: 10.1038/42652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heery DM, Kalkhoven E, Hoare S, Parker MG. 1997. A signature motif in transcriptional co-activators mediates binding to nuclear receptors. Nature 387:733–736. doi: 10.1038/42750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bieker JJ. 2001. Krüppel-like factors: three fingers in many pies. J Biol Chem 276:34355–34358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slavin D, Sapin V, López-Diaz F, Jacquemin P, Koritschoner N, Dastugue B, Davidson I, Chatton B, Bocco JL. 1999. The Krüppel-like core promoter binding protein gene is primarily expressed in placenta during mouse development. Biol Reprod 61:1586–1591. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto N, Kubo A, Liu H, Akita K, Laub F, Ramirez F, Keller G, Friedman SL. 2006. Developmental regulation of yolk sac hematopoiesis by Kruppel-like factor 6. Blood 107:1357–1365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leblanc BP, Stunnenberg HG. 1995. 9-cis retinoic acid signaling: changing partners causes some excitement. Genes Dev 9:1811–1816. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schulman IG, Li C, Schwabe JW, Evans RM. 1997. The phantom ligand effect: allosteric control of transcription by the retinoid X receptor. Genes Dev 11:299–308. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nissen SE, Wolski K. 2007. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 356:2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nissen SE, Wolski K. 2010. Rosiglitazone revisited: an updated meta-analysis of risk for myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality. Arch Intern Med 170:1191–1201. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nesto RW, Bell D, Bonow RO, Fonseca V, Grundy SM, Horton ES, Le Winter M, Porte D, Semenkovich CF, Smith S, Young LH, Kahn R, American Heart Association, American Diabetes Association. 2003. Thiazolidinedione use, fluid retention, and congestive heart failure: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Circulation 108:2941–2948. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000103683.99399.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loke YK, Singh S, Furberg CD. 2009. Long-term use of thiazolidinediones and fractures in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. CMAJ 180:32–39. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piccinni C, Motola D, Marchesini G, Poluzzi E. 2011. Assessing the association of pioglitazone use and bladder cancer through drug adverse event reporting. Diabetes Care 34:1369–1371. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nath S, Mukherjee P. 2014. MUC1: a multifaceted oncoprotein with a key role in cancer progression. Trends Mol Med 20:332–342. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stroopinsky D, Kufe D, Avigan D. 2016. MUC1 in hematological malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma 57:2489–2498. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2016.1195500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mascrez B, Mark M, Dierich A, Ghyselinck NB, Kastner P, Chambon P. 1998. The RXRalpha ligand-dependent activation function 2 (AF-2) is important for mouse development. Development 125:4691–4707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mascrez B, Mark M, Krezel W, Dupé V, LeMeur M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. 2001. Differential contributions of AF-1 and AF-2 activities to the developmental functions of RXR alpha. Development 128:2049–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kastner P, Grondona JM, Mark M, Gansmuller A, LeMeur M, Decimo D, Vonesch JL, Dollé P, Chambon P. 1994. Genetic analysis of RXR alpha developmental function: convergence of RXR and RAR signaling pathways in heart and eye morphogenesis. Cell 78:987–1003. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sucov HM, Dyson E, Gumeringer CL, Price J, Chien KR, Evans RM. 1994. RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes Dev 8:1007–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palijan A, Fernandes I, Bastien Y, Tang L, Verway M, Kourelis M, Tavera-Mendoza LE, Li Z, Bourdeau V, Mader S, Yang XJ, White JH. 2009. Function of histone deacetylase 6 as a cofactor of nuclear receptor coregulator LCoR. J Biol Chem 284:30264–30274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.045526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bajpe PK, Heynen GJ, Mittempergher L, Grernrum W, de Rink IA, Nijkamp W, Beijersbergen RL, Bernards R, Huang S. 2013. The corepressor CTBP2 is a coactivator of retinoic acid receptor/retinoid X receptor in retinoic acid signaling. Mol Cell Biol 33:3343–3353. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01213-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palijan A, Fernandes I, Verway M, Kourelis M, Bastien Y, Tavera-Mendoza LE, Sacheli A, Bourdeau V, Mader S, White JH. 2009. Ligand-dependent corepressor LCoR is an attenuator of progesterone-regulated gene expression. J Biol Chem 284:30275–30287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.051201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perissi V, Staszewski LM, McInerney EM, Kurokawa R, Krones A, Rose DW, Lambert MH, Milburn MV, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. 1999. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes Dev 13:3198–3208. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu X, Lazar MA. 1999. The CoRNR motif controls the recruitment of corepressors by nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 402:93–96. doi: 10.1038/47069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ottersbach K, Dzierzak E. 2005. The murine placenta contains hematopoietic stem cells within the vascular labyrinth region. Dev Cell 8:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rhodes KE, Gekas C, Wang Y, Lux CT, Francis CS, Chan DN, Conway S, Orkin SH, Yoder MC, Mikkola HK. 2008. The emergence of hematopoietic stem cells is initiated in the placental vasculature in the absence of circulation. Cell Stem Cell 2:252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanaka S, Kunath T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nagy A, Rossant J. 1998. Promotion of trophoblast stem cell proliferation by FGF4. Science 282:2072–2075. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stewart SA, Dykxhoorn DM, Palliser D, Mizuno H, Yu EY, An DS, Sabatini DM, Chen IS, Hahn WC, Sharp PA, Weinberg RA, Novina CD. 2003. Lentiviris-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA 9:493–501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2192803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heckl D, Kowalczyk MS, Yudovich D, Belizaire R, Puram RV, McConkey ME, Thielke A, Aster JC, Regev A, Ebert BL. 2014. Generation of mouse models of myeloid malignancy with combinatorial genetic lesions using CRISPR-CAS9 genome editing. Nat Biotechnol 32:941–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reed SE, Staley EM, Mayginnes JP, Pintel DJ, Tullis GE. 2006. Transfection of mammalian cells using linear polyethylenimine is a simple and effective means of producing recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors. J Virol Methods 138:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S, Huang LW, Snow KJ, Ablamunits V, Hasham MG, Young TH, Paulk AC, Richardson JE, Affourtit J, Shalom-Barak T, Bult CJ, Barak Y. 2007. A mouse model of conditional lipodystrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:16627–16632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707797104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]