Abstract

Background

It has been hypothesized that life threatening events are caused by supra-esophageal reflux (SER) of gastric contents which activates laryngeal chemoreflex-stimulated apnea. Placing infants supine decreases the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The aim of this study was to determine whether body position affects esophageal reflexes that control SER.

Methods

We instrumented the pharyngeal and esophageal muscles of decerebrate cats (N=14) to record EMG or manometry, and investigated the effects of body position on the esophago-upper esophageal sphincter (UES) contractile reflex (EUCR), esophago-UES relaxation reflex (EURR), esophagus-stimulated pharyngeal swallow response (EPSR), secondary peristalsis (SP), and pharyngeal swallow (PS). EPSR, EUCR, and SP were activated by balloon distension, EURR by air pulse, and PS by nasopharyngeal water injection. The esophagus was stimulated in the cervical, proximal thoracic, and distal thoracic regions. The threshold stimulus for activation of EUCR, EURR and PS, and the chance of activation of EPSR and SP were quantified.

Results

We found that only EPSR was significantly more sensitive in the supine vs prone position regardless of the stimulus or the position of the stimulus in the esophagus.

Conclusion

We hypothesize that the EPSR may contribute to the protection of infants from SIDS by placement in the supine position.

Background

Life threatening events and troublesome symptoms in infants range from brief resolved unexplained events to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). The mechanism of SIDS is not well understood, but many possible explanations have been proposed. One hypothesis suggests that during sleep infants have reduced swallowing which reduces their ability to remove or prevent gastro-esophageal reflux from reaching the pharynx and stimulating laryngeal receptors causing apnea (1–12). Although there is evidence for each of these steps, it is unknown which portion of this mechanism is defective in infants who experience life threatening events, including SIDS.

Studies have also found that SIDS is significantly reduced by placing the infants on their backs while sleeping (1, 2). This procedure suggests that the position of the body is critical to inhibiting or stimulating a function extremely important in causing SIDS. If SIDS is due to an inciting agent caused by gastro-esophageal reflux or some form of esophago-pharyngeal provocation, then perhaps an airway protective function is missing or inhibited in the prone vs the supine position.

Recently a new reflex response, the esophagus-stimulated pharyngeal swallow response (EPSR), has been characterized and the sensory-motor characteristics defined in the feline model (13). The EPSR has been found to be activated by mechano-distension or chemo-sensitive provocation of the esophagus in human infants (14, 15) and animals (13), but not human adults (16–18). Pharyngeal swallowing is very protective of the larynx as it has been shown to be “the most effective mechanism for esophageal acid clearance” (19). Therefore, if the EPSR is inhibited or absent in some infants they could be prone to supra-esophageal reflux stimulation of the larynx leading to apnea and SIDS.

The aim of this study was to determine whether any of the esophageal reflexes capable of effecting supra-esophageal reflux are modified by body position. Therefore, we tested the effects of body position, i.e., prone vs supine, on the sensitivity to activate the pharyngeal swallow, EPSR, esophago-UES contractile reflex, secondary peristalsis, or esophago-UES relaxation reflex.

Methods

A. Experimental model

We chose to use the decerebrate cat model for these studies for a number of reasons. Firstly, the anatomy and physiology of the larynx and pharynx of the human infant, as opposed to the human adult, is very similar to that of animals, including the cat, and SIDS is a disorder of human infants. In both animals and human infants the larynx is elevated and the epiglottis does not fold back during swallowing (20, 21). These factors allow an intranarial larynx which produces separate respiratory and digestive tracks (20, 21). In addition, the cat laryngeal and pharyngeal anatomy does not change significantly during development (21). Secondly, in no other research animal, but the cat, has all of the identified human esophageal reflexes been identified and characterized including the EPSR (13, 22, 23), which is unique to human infants. Thirdly, the decerebrate cat is an excellent model for investigating brain stem mediated reflexes as it allows research investigation without the significant neural inhibition caused by analgesics or anesthetics. While gas anesthesia is used for the decerebration procedure the animal is anesthetized for less than fifteen minutes, and experiments are begun at least three hours after the anesthetic has been removed. All of the reflexes investigated are mediated by the brain stem (24–27) and prior studies have found that the esophageal reflexes in the decerebrate cat model have a similar sensitivity as in the awake human (23).

B. Animal Preparation

All studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Cats (N=14) were fasted overnight and decerebrated. The animals were anesthetized using isoflurane (3%), the ventral neck region was exposed, the trachea was intubated, and the carotid arteries were ligated. The skull was exposed, and a hole over a parietal lobe was made using a trephine. The hole was enlarged using rongeurs, the central sinus was ligated and cut, and the brain was severed midcollicularly using a metal spatula. The forebrain was then suctioned out of the skull, and the blood vessels of the Circle of Willis were coagulated by suction through cotton balls soaked in warm saline. The boney sinuses were filled with bone wax, the exposed brain was covered with paraffin oil-soaked cotton balls, and the skin over the skull was sewn closed. The animals were then placed supine on a heating pad (Harvard Homeothermic monitor), and the body temperature was maintained between 38 and 40°C.

After decerebration all animals received the following surgical preparation. An incision was made on the ventral surface of the neck, and the larynx and pharynx were exposed. The trachea was cannulated, EMG electrodes were placed on the geniohyoideus, thyrohyoideus, thyropharyngeus, cricopharyngeus, and esophagus 2 and 4 cm from the cricopharyngeus. The cricopharyngeus is the primary muscle (3, 6) of the upper esophageal sphincter, and its actions are considered responses of the upper esophageal sphincter. The abdomen was then opened along the ventral midline and a fistula of the proximal stomach was formed using a 3 ml plastic syringe that exited the abdominal cavity. This fistula was used to insert stimulation devices into the esophagus without disturbing the pharynx or larynx. The abdomen was then closed with sutures.

C. Stimulation Techniques

The esophagus was stimulated in four different ways as certain esophageal reflexes are most likely to occur in one of these ways (Fig. 1). The balloon stimulation methods all used a 3 cm long balloon made from the finger of a latex surgical glove, and the balloon distension diameters were calibrated before the experiments. The pressure within the balloon was recorded by a Statham pressure transducer (P23) which was attached to a low level DC amplifier (Grass Model 7 P122) and used as a stimulus marker.

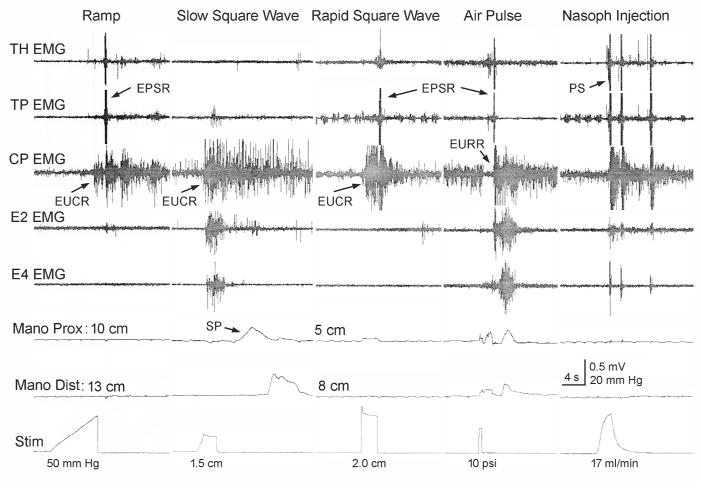

Figure 1. Types of stimuli applied and possible responses.

The possible responses to balloon and air stimulation of the esophagus and water stimulation of the nasopharynx are illustrated. The balloon stimulations were in the form of a ramp, slow square wave, or rapid square wave. The ramp stimulus activated esophago-UES contractile reflex and EPSR. The slow square wave stimulus activated upper esophageal sphincter and secondary peristalsis. The rapid square wave stimulus activated esophago-UES relaxation reflex and EPSR. The air pulse stimulation activated esophago-UES relaxation reflex and EPSR. The nasopharyngeal stimulation activated PS. TH, thyrohyoideus; TP, thyropharyngeus; CP, cricopharyngeus; EMG, electromyography; E#, esophagus #cm from the CP; Mano, manometry; prox, proximal; dist, distal; Stim, stimulus artifact; EPSR, esophagus stimulated pharyngeal swallow response; PS, pharyngeal swallow; SP, secondary peristalsis; EUCR, esophago-UES contractile response; EURR, esophago–UES relaxation response; UES, upper esophageal sphincter.

a. Ramp distension

The balloon was inflated at 0.5ml/s until a response was observed or until the balloon was distended 2.5 cm in diameter (N=14). This stimulus activates the esophago-UES contractile reflex and/or the EPSR (Fig. 1).

b. Slow and Rapid Square wave

The balloon was inflated by hand either slowly or rapidly in a square wave fashion from 1 to 2.5 cm in diameter for 3 to 5 s (N=14). The slow distension (Fig. 1) primarily activates the esophago-UES contractile reflex and secondary peristalsis, and the rapid distension primarily activates esophago-UES contractile reflex (Fig. 1), but can also activate EPSR and esophago-UES relaxation reflex.

c. Air pulse

An air pulse of 4 to 15 psi at 0.5 s duration (WPI, Pneumatic Pump, PV820) was injected into a 2 mm diameter catheter with a hole in its side which caused a tangentially applied very mild air pulse to stimulate the esophageal mucosa (N=12). The air pulse activates the esophago-UES relaxation reflex and EPSR (Fig. 1).

The nasopharynx was also stimulated to activate the pharyngeal swallow in order to compare it to the pharyngeal swallow activated by esophageal stimulation, i.e., EPSR (Fig. 1). A 5 Fr enteral feeding tube was inserted 7 cm into the nasal cavity and water was injected at 17 ml/min until swallowing was activated (N=10).

D. Recording Techniques

1. Electromyography

Bipolar Teflon-coated stainless steel wires (AS 636; Cooner Wire, Chatsworth, CA) bared for 2–3 mm were placed in each muscle, and the wires were fed in differential amplifiers (A-M Systems 1800). The electrical activity was filtered (bandpass of 0.1–3.0 KHz) and amplified 1,000 or 10,000 times before feeding into the computer.

2. Manometry

A solid state manometry device with two sensors 3 cm apart (Gaeltec 16CT) was inserted into the esophagus through the gastric fistula and the proximal sensor was placed 3 cm distal to the esophageal stimulating device. The manometry device was attached to low level DC amplifiers (Grass Model 7 P122).

All recorded signals were acquired and analyzed using CODAS hardware and software and stored in the computer.

F. Experimental protocols

The animal was first tied to the experimental table either in the prone or supine position and then when all of the reflexes were tested the animal was turned over and tested again. Half of the animals were tested first on either side. Each esophageal stimulus was applied three times at three different regions of the esophagus: cervical (2 – 5 cm from the cricopharyngeus), proximal thoracic (7 – 10 cm from the cricopharyngeus), and distal thoracic (13 – 16 cm from the cricopharyngeus). The pharyngeal stimulus was applied 5 to 8 times at each body position. The multiple applied stimuli were averaged to obtain the characteristic animal response at each body position and each esophageal location.

G. Data Reduction and Analysis

The activation and magnitude of the esophago-UES contractile reflex and esophago-UES relaxation reflex are directly related to the stimulus intensity (23), therefore, for these variables we quantified the threshold stimulus needed for activation at each esophageal location. The statistical significance of a difference in quantified thresholds (mean ± SE) due to body position at different esophageal locations was calculated using repeated measures two-way ANOVA. On the other hand, secondary peristalsis and EPSR are activated in a probabilistic manner (13), therefore, for these variables we quantified the proportion of stimuli that resulted in a response. The statistical significance of a difference in quantified thresholds (response proportion ± SE) due to body position at different esophageal locations was calculated using repeated measures Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test with the continuity correction. In order to determine the threshold for activation of pharyngeal swallow, the time delay from start of nasopharyngeal injection until the occurrence of the first pharyngeal swallow was quantified. The statistical significance of a difference in quantified time delays (mean ± SE) between prone and supine was calculated using the paired Student’s t-test. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant for all statistical tests.

Results

A. Esophago-UES Contractile Reflex

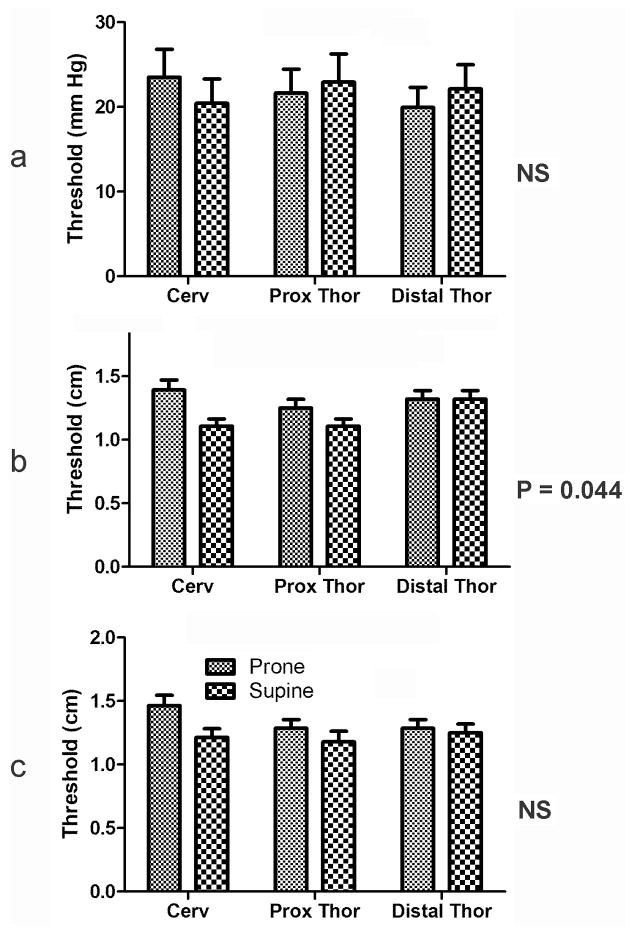

We found that ramp, slow square wave, and rapid square wave distension activated esophago-UES contractile reflex, but only slow square wave stimulation of esophago-UES contractile reflex was significantly affected by body position. The thresholds for activation of esophago-UES contractile reflex were lower in supine vs prone position (Fig. 2), but the response was small, i.e., less than 15% change.

Figure 2. Effects of body position on threshold for activation of esophago-upper esophageal sphincter contractile reflex at different esophageal locations using ramp (a), slow square wave (b) and rapid square wave (c) balloon distension.

The thresholds for activation of upper esophageal sphincter by ramp or rapid square wave stimulation applied across the esophagus did not significantly differ between prone and supine body position. However, placement in the supine vs prone position significantly reduced (P = 0.044) the threshold stimuli needed to activate the upper esophageal sphincter by slow square wave stimulation across the esophagus. Cerv, cervical esophagus; prox; proximal; thor, thoracic.

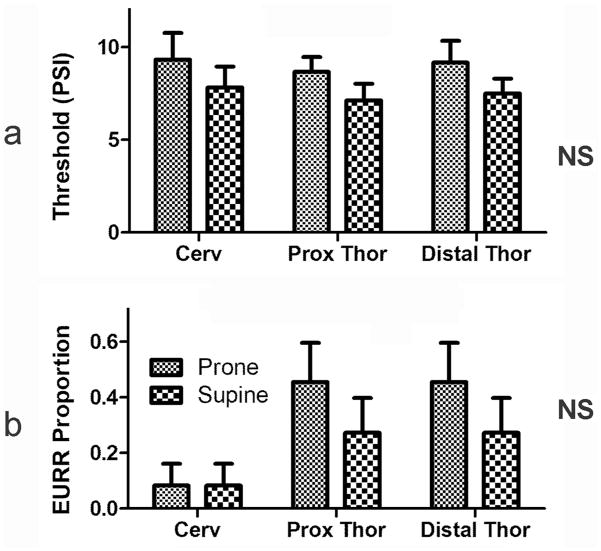

B. Esophago-UES Relaxation Reflex

We found that air pulse stimulation could always activate esophago-UES relaxation reflex at all levels of the esophagus, but the esophago-UES relaxation reflex response to air pulse stimulation of the esophagus was not affected by body position (Fig. 3). Rapid square wave balloon distension also activated the esophago-UES relaxation reflex, but these responses occurred in a probabilistic fashion, therefore, the proportion of stimuli causing responses were tested using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. We found that the proportion of esophago-UES relaxation reflex responses to rapid square wave balloon stimulation of the esophagus did not differ significantly in the supine vs prone position (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Effects of body position on threshold for activation of esophago-upper esophageal sphincter relaxation reflex at different esophageal locations using air pulse (a) and proportion of esophago-UES relaxation reflex activated using rapid square wave (b) balloon stimulation.

Activation of the esophago-UES relaxation reflex was not significantly affected by body position regardless of the stimulus or esophageal location. See Fig 2 for definition of symbols.

C. Esophagus-Stimulated Pharyngeal Swallow Response (EPSR)

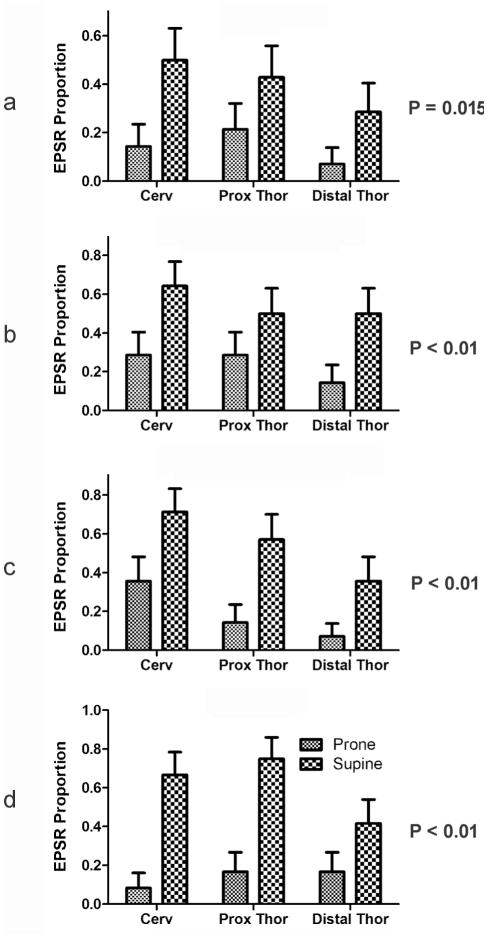

We found that the EPSR was more likely to occur in the supine vs prone position regardless of type of stimulus or the region of the esophagus stimulated (Figs. 4 and 5). In addition, the magnitudes of the differences in responses between supine and prone for all types of stimuli and all esophageal regions were over 100% (Fig. 5).

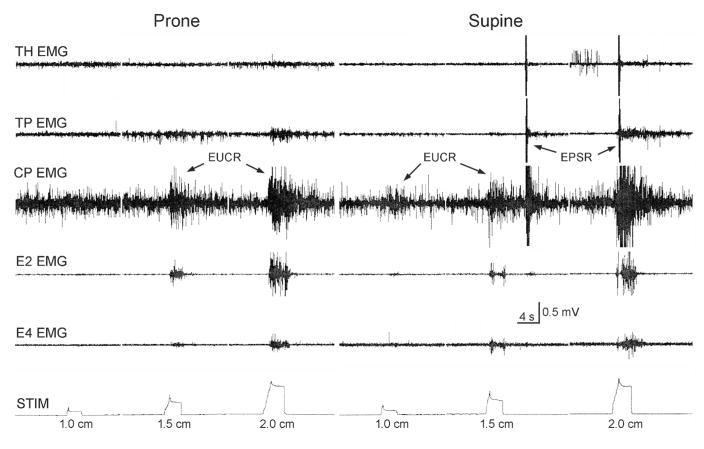

Figure 4. Effects of body position on the activation of the EPSR using slow square wave balloon distension.

Placing the animal in the supine position resulted in slow square wave balloon distension of the cervical esophagus to activate EPSR as well as upper esophageal sphincter, whereas the same stimuli in the prone position only activated upper esophageal sphincter. See Figure 1 for definition of symbols.

Figure 5. Effects of body position on the proportion of stimuli activating the EPSR at different esophageal locations using ramp (a), slow square wave (b) and rapid square wave (c) balloon distension, and air pulse (d) stimulation.

Activation of EPSR by all stimuli and at all regions of the esophagus was significantly (P < 0.05) affected by body position. The supine position caused over a 100% increase in the proportion of stimuli that activated EPSR. EPSR, esophagus-stimulated pharyngeal swallow response. See Figure 1 for definition of symbols.

D. Secondary Peristalsis

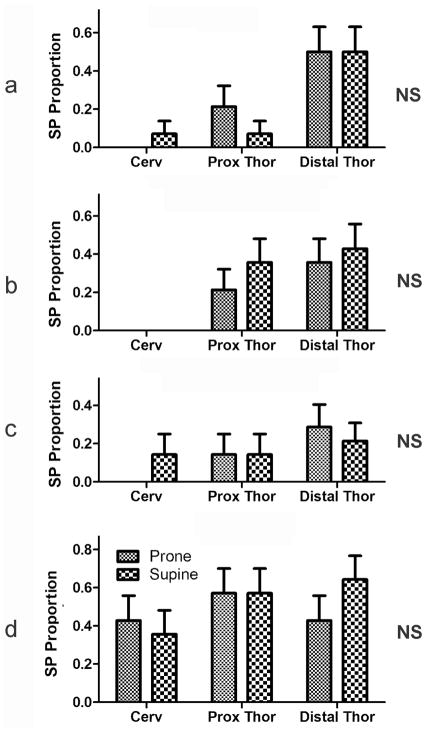

We found that regardless of the stimulus and position in the esophagus, the proportion of stimuli activating secondary peristalsis did not differ significantly between placing the animal prone or supine (Fig 6).

Figure 6. Effects of body position on the proportion of stimuli activating the secondary peristalsis at different esophageal locations using ramp (a) , slow square wave (b) and rapid square wave (c) balloon distension, and air pulse (d) stimulation.

Body position had no significant effect on activation of secondary peristalsis regardless of stimulus or esophageal location. . See Figure 1 for definition of symbols

E. Pharyngeal Swallow

We found that the time delay for activation of the pharyngeal swallow due to nasopharyngeal stimulation was 2.8 ± 0.3 s in prone position vs 2.9 ± 0.2 s in the supine position which was not significantly different (P = 0.85, N=10).

Discussion

We found that of the four esophageal reflexes investigated, i.e., esophago-UES contractile reflex, esophago-UES relaxation reflex, secondary peristalsis and EPSR, only one of them, i.e. EPSR, was significantly more sensitive to all stimuli and all esophageal regions when the animal was in the supine as opposed to the prone position. However, it is unknown whether this effect is inhibition in the prone position or excitation in the supine position. In addition, the effect on EPSR was a large increase, i.e. greater than 100% change, in the proportion of successful stimuli in the supine vs prone position for all stimuli at all esophageal locations.

Considering that this study was conducted in an animal in which the normal physiological state of brain stem reflexes was preserved, our results should reflect normal physiological function. In the normal situation in animals, the response to gastro-esophageal reflux is either secondary peristalsis or EPSR. We hypothesize that the decreased sensitization of EPSR, but not secondary peristalsis, in the prone position is related to the laryngeal/pharyngeal anatomy of animals. In mammals the larynx is high in the neck with a small supra-laryngeal area of the pharynx and significantly reduced nasal and laryngeal segments. “The high position of the larynx enables the epiglottis to pass up behind the soft palate and to allow the larynx to open directly into the nasopharynx” (19). The epiglottis acts to separate the digestive from respiratory tract by its close contact with the soft palate and does not move to cover the trachea during swallowing. This allows the soft palate to provide “a direct airway from the nose to the lungs, while the alimentary tract can pass around the larynx en route to the esophagus” (21). Therefore, if supra-esophageal reflux of gastric contents were to occur in an animal in the prone position the possibility of aspiration and/or laryngeal contact would be high due to gravity and the dorsal position of the esophagus relative to the trachea. When in the prone position, the preferred response to gastro-esophageal reflux would be secondary peristalsis. When in the supine position, the preferred response to gastro-esophageal reflux, in order to prevent supra-esophageal reflux, is the EPSR. This is because there is little risk of aspiration due to gravity of any supra-esophageal reflux and the pharyngeal swallow by definition is very effective in clearing the pharynx and has been shown to be “the most important mechanism” for clearing the esophagus of gastro-esophageal reflux (19).

One might hypothesize that a better way to prevent supra-esophageal reflux is to increase secondary peristalsis and/or the esophago-UES contractile reflex rather than to increase EPSR. However, studies indicate that esophageal acid exposure in humans with reflux disease (28) and acute esophageal acid exposure in experimental animals (29) are both associated with increased reflex relaxation of the UES and a decrease in the sensitivity of the esophago-UES contractile reflex. In addition, gastro-esophageal reflux in humans is associated with a decrease in secondary peristalsis and an increase in non-peristaltic esophageal contractions (19, 28). In contrast, esophageal acid exposure in experimental animals increases the incidence and sensitivity to activation of the EPSR (13). Therefore, although the esophago-UES contractile reflex and secondary peristalsis may function in part to prevent supra-esophageal reflux, studies have shown that both reflexes are inferior to the EPSR in this regard.

The sensitivity of the other reflexes to one body position over the other has no physiological advantage. The pharyngeal swallow is a swallow activated by material in the pharynx which will respond no differently from any swallow. The material will follow the digestive tract down without entering the airway whether the animal is prone or supine. The esophago-UES contractile reflex acts to close the upper esophageal sphincter (18, 22) and prevent to supra-esophageal reflux , therefore it will protect the airway whether the animal is prone or supine. The esophago-UES relaxation reflex is designed to open the upper esophageal sphincter (22) and participate in physiologically appropriate to supra-esophageal reflux, but the refluxate is air not fluid, as this reflex is activated as part of the belch response (22, 23). Therefore, the fact that body position had no effect on the pharyngeal swallow, secondary peristalsis, and esophago-UES relaxation reflex is consistent with the physiological function of these reflex responses.

Our finding that body position altered the EPSR, but not pharyngeal swallow response, suggests that the effects of body position are not on the neural mechanisms controlling the swallow motor event, e.g. DMN or NA (8, 30–32), but on the sensory pathway or central neural circuitry, e.g., NTS (8, 30, 31), controlling the pharyngeal swallow.

The effect of body position on digestive tract function, especially the EPSR, is well supported by histological and neurophysiological findings. Vestibular inputs have been found to converge with vagal inputs throughout the medial and intermediate portions of the NTS (33, 34), and c-Fos studies have found that the pharyngeal swallow is mediated by neurons of the intermediate, interstitial, and ventromedial nuclei of the NTS (25). In addition, it was found that rapid distension of the esophagus, which we found best activated the EPSR, best activates the intermediate, interstitial, and dorsomedial nuclei of the NTS (27). Therefore, our findings that body position primarily affects the EPSR are consistent with histological and neurophysiological studies.

The ability of the vestibular nucleus to alter basic physiology of the digestive tract is not unique, as the vestibular nucleus has also been found to have significant effects on cardiovascular (34, 35) and respiratory (36, 37) function and reflexes. Therefore, it is unlikely that the effects of body position on EPSR are specific to this reflex, and this effect may be one aspect of a more general alteration in autonomic function by the vestibular system (35).

The fact that body position has significant effects on EPSR sensitivity in animals may have important significance for human infants. As we reported in our prior study (13), the EPSR is only found in animals and human infants, and not in human adults. It is unknown when humans grow out of the EPSR, but they have the reflex for at least three months (14, 15). Since human infants spend their time either supine or prone (as during kangaroo care bonding or when rolled over from supine) as do animals, it is highly likely that the EPSR has a similar function in human infants as it does in animals. That is, the EPSR in human infants may be airway protective especially when in the supine position, and that this mechanism might be blunted in the prone position. Studies in human infants are needed to address this issue.

It is known that swallowing and related reflexes are significantly inhibited in sleep compared to the awake state (38), especially when the infant is in the prone position (3 – 7, 39, 40). If EPSR also has significantly reduced sensitivity in the prone position in human infants, as it does in animals, then this might explain why infants are prone to SIDS when they are in the prone position and why placing them in the supine position is protective of SIDS. Studies in animals (12, 41) and human infants (42) have shown that supra-esophageal reflux can activate laryngeal chemoreflex induced apnea that may be the cause of SIDS, and that swallowing is the “principal airway protective response to the presence of fluid in the pharynx in both active and quiet sleep” (4). Therefore, the inhibition of EPSR in the prone position in human infants might allow supra-esophageal reflux to cause SIDS.

The primary limitations of this study are that we used an animal model to study human physiology, and we used an adult to study the immature. Animal models must be used to study human physiology when invasive techniques are required, and as we presented previously we have proven in many publications (13, 22 – 27, 29) that the cat is an excellent model of the human infant physiological functions (14, 15) which we studied.. Since our goal was to relate our findings to the human infant it would seem that using an infant cat might be a more appropriate model. However, it is unknown whether the reflexes we studied in the adult cat exist in the infant cat, as no one has studied these reflexes in the infant cat. Regardless, this is a relatively minor issue, because while the humans goes through major changes during maturation in systems involved in the reflux theory of SIDS, animals, including the cat, do not. These changes include: 1) a largely horizontal existence to a vertical existence; 2) no speech to speech; 3) feeding in a manner in which the valeculae are filled by multiple oral phases of swallowing, i.e. sucks, followed by activation of one combined pharyngeal and esophageal phase of swallowing, to a state in which the bolus is swallowed in one continuous motion consisting of all three phases of swallowing (14, 15); 4) the larynx descends a significant amount resulting in a larger supralaryngeal portion of the pharynx required for speech (21); and 5) the epiglottis separates from the soft palate resulting in the airway and digestive tracts sharing the same pathway (21). During maturation animals may undergo changes in the magnitudes of some cardiorespiratory responses (43 – 45), but the only change observed in cats in a system related to the current study is a tilting of the epiglottis during swallowing (20) which alters the magnitudes of some measured swallow related variables. Therefore, there is no animal model of human maturation process related to the reflux theory of SIDS. However, it was never our attempt to model SIDS, but to model the human infant. As mentioned previously, the mature cat exhibits all of the major anatomical and physiological characteristics of the pharynx, larynx, and esophagus as the human infant (14, 15). Therefore, for the purposes of the current study, the adult cat is the best animal model available.

We conclude that body position affects EPSR, whose primary function is to protect the airway from to supra-esophageal reflux, and EPSR is more readily activated in the supine vs prone body position. Considering that 1) supra-esophageal reflux is more of a threat for exposure of the larynx to gastro-esophageal reflux in human infants than adults due to infant laryngeal and pharyngeal anatomy and physiology, 2) the EPSR is very effective at clearing the esophagus of gastro-esophageal reflux and preventing to supra-esophageal reflux, 3) the EPSR readily occurs in humans infants but not adults, and 4) placing human infants in the supine position reduces the incidence of SIDS; we hypothesize that sensitization of EPSR in the supine position may significantly contribute to the protection of infants from SIDS. More studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis, especially in vulnerable human infants during maturation and those with neuropathy.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported in part by NIH grants RO1 DK-25731 (Shaker), RO1 DK-068158 (Jadcherla), and PO1-068051 (Shaker, Lang, Jadcherla).

We acknowledge the statistical assistance of Dr. Aniko Szabo.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Dwyer T, Ponsonby AL. Sudden infant death syndrome and prone sleeping position. Annals of Epidemiology. 2009;19:245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert R, Salanti G, Harden M, See S. Infant sleeping position and the sudden infant death syndrome: systematic review of observational studies and historical review of recommendations from 1940 to 2002. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;34:874–887. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeffrey HE, Megevand A, Page M. Why the prone position is a risk factor for sudden infant death syndrome. Pediatrics. 1999;104:263–269. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeffrey HE, Page M, Post EJ, Wood AKW. Physiological studies of gastro-oesophageal reflux and airway protective response in the young animals and human infant. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:544–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leiter JC, Bohm I. Mechanisms of pathogenesis in the sudden infant death syndrome. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:127–138. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orr WC, Heading R, Johnson LF, Kryger M. Review Article: sleep and its relationship to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page M, Jeffrey H. The role of gastro-oesophagael reflux in the aetilogy of SIDS. Early Human Develop. 2000;59:127–149. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(00)00093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sang Q, Goyal RK. Swallowing reflex and brain stem neurons activated by superior laryngeal nerve stimulation in the mouse. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:G191–G200. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.2.G191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slocum C, Hibbs AM, Martin RJ, Orenstein SR. Infant apnea and gastroesophageal reflux: a critical review and framework for further investigation. Current Gastroenterol Reports. 2007;9:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thach B. Tragic and sudden death. Potential and proven mechanisms causing sudden infant death syndrome. EMBO reports. 2008;9:114–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thach BT. The role of respiratory control disorders in SIDS. Resp Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;149:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetmore RF. Effects of acid on the larynx of maturing rabbit and their possible significance to the sudden infant death syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1242–1253. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang IM, Medda BK, Jadcherla SR, Shaker R. Characterization and mechanisms of the pharyngeal swallow activated by stimulation of the esophagus. Am J Physiol. 2016;311:G827–G837. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00291.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jadcherla SR, Duing HQ, Hoffman RG, Shaker R. Esophageal body and upper esophageal motor responses to esophageal provocation during maturation in preterm newborns. J Pediatr. 2003;143:31–38. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(03)00242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadcherla SR, Hoffman RG, Shaker R. Effect of maturation of the magnitude of mechanosensitive and chemosensitive reflexes in the preterm human esophagus. J Pediatr. 2006;149:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babaei A, Dua K, Naini SR, et al. Response of the upper esophageal sphincter to esophageal distension is affected by posture, velocity, volume, and composition of the infusate. Gastroenteroloy. 2012;142:734–743. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creamer B, Schlegel J. Motor responses of the esophagus to distension. J Appl Physiol. 1957;10:498–504. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1957.10.3.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enzmann DR, Harell GS, Zboralske FF. Upper esophageal responses to intraluminal distension in man. Gastroenteroloy. 1977;72:1292–1298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bremner RM, Hoeft SF, Costantini M, Crookes PF, Bremner CG, Demeester TR. Pharyngeal swallowing. The major factor in clearance of esophageal reflux episodes. Ann Surgery. 1993;218:364–370. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199309000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crompton AW, German RZ, Thexton AJ. Development of the movement of the epiglottis in infant and juvenile pigs. Zoology. 2008;111:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laitman JT, Reidenberg JS. Specialization of the human upper respiratory and upper digestive systems as seen through comparative and developmental anatomy. Dysphagia. 1993;8:318–325. doi: 10.1007/BF01321770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Mechanism of reflexes induced by esophageal distension. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:G1246–1263. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Mechanism of UES relaxation initiated by gastric air distension. Am J Physiol. 2014;307:G452–G458. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00120.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang IM. Brain stem control of the phases of swallowing. Dysphagia. 2009;24:333–338. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9211-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang IM, Dean C, Medda BK, Aslam M, Shaker R. Differential activation of vagal medullary nuclei during different phases of swallowing. Brain Res. 2004;1014:145–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Differential activation of pontomedullary nuclei by acid perfusion of different regions of the esophagus. Brain Res. 2010;1352:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Differential activation of medullary vagal nuclei caused by stimulation of different esophageal mechanoreceptors. Brain Res. 2011;1368:119–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babaei A, Lang IM, Massey B, Shaker R. Impaired esophageal reflexes in supra-esophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1381–1391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang IM, Medda BK, Shaker R. Effect of esophageal acid exposure on esophageal reflexes. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:M342. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bieger D, Neuhuber W. Neural circuits and mediators regulating swallowing in the brainstem. GI Motility Online. 2006 doi:10,1038/gimo74. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jean A. Brain stem control of swallowing: neuronal network and cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:929–969. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zoungrana OR, Amri M, Car A, Roman C. Intracellular activity of motoneurons of the rostral nucleus ambiguous during swallowing in sheep. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:909–922. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balaban CD, Beryozkin G. Vestibular nucleus projection to nucleus tractus solitarius and the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve: potential substrate for vestibulo-autonomic interactions. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98:200–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00228409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yates BJ. Vestibular influences on the sympathetic nervous system. Brain Res Rev. 1992;17:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(92)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yates BJ, Gtrelot I, Kerman IA, Balaban CD, Jakus J, Miller AD. Organization of vestibular inputs to nucleus tractus solitarius and adjacent structures in cat brain stem. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R974–R983. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.4.R974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yates BJ, Jakus J, Miller AD. Vestibular effects ion respiratory outflow in the decerebrate cat. Brain Res. 1993;629:209–217. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91322-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng Y, Umezaki T, Nakazawa K, Miller AD. Role of pre-inspiratory neurons in vestibular and laryngeal reflexes and in swallowing and vomiting. Neuroscience Letters. 1997;225:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jadcherla SR, Chan CY, Fernandez S, Splaingard M. Maturation of upstream and downstream reflexes in human premature neonates: the role of sleep and awake states. Am J Physiol. 2013;305:G649–G658. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00002.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKelvey GM, Post EJ, Wood AKW, Jeffrey HE. Airway protection following simulated gastroesophageal reflux in sedated and sleeping neonatal piglets during active sleep. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:533–539. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sondheimer JM. Clearance of spontaneous gastroesophageal; reflux in awake and sleeping infants. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:821–826. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91484-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harned HS, Myracle J, Ferreiro J. Respiratory suppression and swallowing from introduction of fluids into the laryngeal region of the lamb. Pediatr Res. 1978;12:1003–1009. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197810000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davies AM, Koenig JS, Thach BT. Upper airway chemoreflex responses to saline and water in preterm infants. J Appl Physiol. 1988;64:1412–1420. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.4.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobi MS, Thach BT. Effect of maturation on spontaneous recovery from hypoxic apnea by gasping. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:2384–2390. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.5.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thach BT. Maturation of cough and other reflexes that protect the fetal and neonatal airway. Pulmon Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wyszogrodski I, Thach BT, Milic-Emili J. Maturation of respiratory control in unanesthetized newborn rabbits. J Appl Physiol: Respirat Environ Exercise Physiol. 1978;44:304–310. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1978.44.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]