Abstract

Despite high rates of suicidal ideation and behavior in youth with pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD), little work has examined how psychosocial interventions impact suicidality among this high-risk group. The current study examined suicidal ideation outcomes in a randomized clinical trial comparing Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CFF-CBT) for PBD versus psychotherapy treatment-as-usual (TAU). Although not designed for suicide prevention, CFF-CBT addresses child and family factors related to suicide risk and thus was hypothesized to generalize to the treatment of suicidality. Participants included 71 youth aged 7–13 years (M=9.17, SD=1.60) with DSM-IV-TR bipolar I, II, or not otherwise specified randomly assigned, with parent(s), to receive CFF-CBT or TAU. Both treatments consisted of 12 weekly and 6 monthly booster sessions. Suicidal ideation was assessed via clinician interview at baseline, post-treatment, and 6-month follow-up. Results indicated that suicidal ideation was prevalent pre-treatment: 39% of youth reported current suicidal thoughts. All youth significantly improved in the likelihood and intensity of ideation across treatment, but group differences were not significant. Thus, findings suggest that early intervention for these high-risk youth may reduce suicidal ideation, and at this stage of suicidality, youth may be responsive to even non-specialized treatment.

Keywords: Pediatric bipolar disorder, suicide prevention, cognitive-behavioral therapy, family-focused intervention, randomized clinical trial

Introduction

Suicidality in pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD) is an extreme, yet largely unaddressed, public health concern. Pediatric bipolar disorder is a chronic and debilitating illness characterized by periods of episodic mood disturbance (i.e. elevated mood and/or significant irritability), associated psychosocial impairment (West & Pavuluri, 2009), and the highest risk for completed suicide of all youth disorders (Brent et al., 1993). Specifically, up to 50% of youth with bipolar disorder will attempt suicide by age 18 (Bhangoo et al., 2003; Goldstein et al., 2012; Lewinsohn, Seeley, & Klein, 2003), thus constituting a key at-risk group for targeted suicide prevention efforts. Although suicidal behaviors tend to peak in the adolescent years (Brent et al., 2013), suicidality in younger children with PBD is also highly prevalent: children with PBD report rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors ranging from 20%–55% in pediatric samples (Algorta et al., 2011; Goldstein et al., 2009; Jolin, Weller, & Weller, 2007; Weinstein, Van Meter, Katz, Peters, & West, 2015). Among younger ideators, risk for suicide attempts is greatest in the year following ideation onset (Nock et al., 2008). As such, the early identification and intervention of suicidal ideation in this younger population—before youth progress to more severe behavior—is essential to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with PBD.

In spite of the alarming rates of suicidality in PBD, effective suicide prevention interventions for this high-risk group are limited. Whereas the examination of psychosocial interventions for youth suicide has increased dramatically in the past decade, with reviews highlighting six treatments of varying orientations as possibly to probably efficacious based on positive findings from a single randomized clinical trial (RCT; see reviews by Glenn et al., 2015; Brent et al., 2013), these interventions primarily target adolescents (versus children) and studies rarely include any youth with bipolar disorder. Indeed, in a recent review of the current evidence base of psychosocial treatments for youth suicidal thoughts and behaviors, none of the reviewed studies included youth with bipolar disorder (Glenn et al., 2015). In one notable exception (not included in the review), Goldstein and colleagues conducted a pilot RCT of Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A) with bipolar disorder, with promising findings indicating a trend for improved suicidal ideation for youth receiving DBT-A versus treatment as usual (Goldstein et al., 2015). However, no studies to date have addressed the treatment of suicidality in preadolescents with bipolar disorder, despite our research documenting the early emergence of suicidality in these youth.

The development of suicide interventions for preadolescent youth with PBD may be informed by existing evidenced-based treatments that address the constellation of psychosocial factors posited to relate to suicidality in this young population. In particular, family and cognitive factors have been linked to suicidal ideation and behaviors in PBD, including family conflict and lower family adaptability (Algorta et al., 2011; Goldstein et al., 2009; Weinstein, Van Meter, et al., 2015), and low self-esteem (Weinstein, Van Meter, et al., 2015). Coping skills deficits and affect regulation have also been highlighted as key risk factors for youth suicidality in the extant literature (Bridge, Goldstein, & Brent, 2006; Esposito, Spirito, Boergers, & Donaldson, 2003; Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1996). One of the few treatments for PBD that has garnered empirical support is Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CFF-CBT), which was developed as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy to target the unique symptoms (e.g., rapid cycling, comorbid disorders, mixed mood states) and global impairments of school-age children and preadolescents (ages 7–13 years) with PBD and their families (Pavuluri, Graczyk, et al., 2004; West et al., 2014). Grounded in the neuroscience and psychosocial research on PBD, this manualized treatment integrates cognitive behavioral therapy with elements of positive psychology, interpersonal, and mindfulness approaches to target the range of needs of families affected by PBD. CFF-CBT incorporates an intense focus on parent/family therapy to address parents’ therapeutic needs and the impact of PBD on parenting (e.g., parental well-being, family stress; Keenan-Miller et al., 2012; Schenkel et al., 2008) alongside individual child work. Although not specifically designed to target suicidality, the core components of CFF-CBT address the affective, cognitive, and family processes that may lead to or maintain suicidal thoughts and behaviors by aiming to (1) improve affect regulation; (2) increase problem-solving, hope, and self-esteem; and (3) improve family adaptability and conflict. Thus, CFF-CBT may generalize to the treatment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with PBD.

Our prior work has found that CFF-CBT demonstrated feasibility and acceptability to families, and was superior to a dose-matched psychotherapy treatment-as-usual control in improving mania and depression symptoms and global functioning in a randomized trial (West et al., 2014) with particular strength for families with greater parental depression symptoms and lower income (Weinstein, Henry, Katz, Peters, & West, 2015). In addition, even in this young sample of youth aged 7–13 years, nearly half of participants reported current suicidal ideation at baseline (Weinstein, Van Meter, et al., 2015). The current study, designed as a complementary study to the RCT, builds on previous work by examining change in suicidality in youth ages 7–13 with PBD receiving CFF-CBT versus control across treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Given the overlap between core treatment ingredients in CFF-CBT and key factors related to suicidality in youth, we hypothesized that CFF-CBT would be associated with clinically significant improvements in the primary outcome of suicidal thoughts as compared to the psychotherapy-as-usual control. Exploratory analyses also aimed to examine change in the lower-frequency suicidal behaviors across treatment.

Method

Participants

Participants were youth (N=71) diagnosed with a bipolar spectrum disorder recruited from a specialty mood disorders clinic in a large Midwestern urban academic medical center from 2010–2014 to participate in a psychosocial RCT for PBD (for details and consolidated standards of reporting trials [CONSORT] diagram, see West et al., 2014). Additional funding was received from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to conduct this study; as a result, two additional youth were included in this sample and attrition information specific to this study is reported below. Notably, as this sample was drawn from the main RCT for PBD, youth were not recruited based on current suicidality. Youth meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for bipolar spectrum disorders (I, II, and not otherwise specified (NOS)) aged 7–13 were eligible to participate. BP-NOS was defined using DSM-IV-TR criteria as the presence of depression and mania symptoms that met symptom severity threshold but not minimal duration criteria, or the presence of recurrent hypomanic episodes without intercurrent depressive symptoms. Inclusion criteria included: parental consent, youth assent, and youth stabilized on medication, defined as scores of ≤ 20 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; Young, Biggs, Ziegler, & Meyer, 1978) and < 80 on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS; Poznanski et al., 1984), indicating no acute, severe symptoms requiring immediate, more intensive care. If the child scored above threshold on these measures, their prescribing psychiatrist in the specialized mood disorders clinic was consulted to determine whether they were stable enough to benefit from the outpatient research protocol or a higher level of care was necessary. Exclusion criteria included: youth IQ < 70 on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Scale-Second Edition (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004), active psychosis, active substance abuse or dependence, or neurological/medical problems that significantly complicate psychiatric symptoms, determined by the Washington University Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS; Geller et al., 1996); and current severe suicidality with intent or plan requiring immediate hospitalization, as measured by the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2011), though no youth were excluded for this reason. Additionally, youth whose primary caretaker was experiencing a current depressive or manic episode, indicated by Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) score ≥28 and Altman’s Self-Report of Mania (ASRM; Altman et al., 2001) score > 6, were excluded; again, no youth were excluded for this reason. Youth with comorbid disorders, including high functioning autism, were included to ensure an optimally clinically relevant sample.

Procedures

Diagnosis and Randomization

Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Eligibility was assessed by trained raters (licensed clinical psychologists and doctoral students). After obtaining informed consent, parents were interviewed using the Washington University Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS; Geller et al., 1996), with portions of the Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL; Geller et al., 1996; Raison et al., 2006) used to define mood episodes, and corroborating information from child-report. Diagnostic interviews were reviewed during study meetings with clinicians specialized in PBD (first author, S.M.W.; RCT PI and co-author A.E.W.) for final determination. Youth meeting diagnostic criteria for a bipolar spectrum disorder completed the baseline assessment and were randomized to study condition using Research Randomizer software (Urbaniak & Plous, 1997). Outcome assessments for this study were conducted by a blinded rater at post-treatment (12 weeks) and a 6-month follow-up (39 weeks).

Psychosocial Intervention

Youth and their parents were randomly assigned to CFF-CBT (n = 35) via a specialty mood disorders clinic or psychotherapy treatment-as-usual (TAU; n = 36) via a general child psychiatry clinic. Both clinics were located within the same outpatient psychiatry program. Families in both conditions received 12 weekly 60–90 minute sessions and up to 6 monthly booster sessions. CFF-CBT study therapists were clinical psychology pre- and post-doctoral trainees (N= 23) who received a three-hour initial training on CFF-CBT and weekly expert supervision. CFF-CBT sessions alternate between parent, child, and family, and include seven components that comprise the treatment acronym, “RAINBOW”: Routine (developing consistent daily routines), Affect Regulation (psychoeducation about feelings; mood monitoring; coping strategies to improve mood regulation), I Can Do It! (improving child self-esteem and parent self-efficacy), No Negative Thoughts/Live in the Now (cognitive restructuring and mindfulness techniques to reduce negative thoughts for child and parent), Be a Good Friend/Balanced Lifestyle (social skill-building for child; improving parent self-care), Oh How Do We Solve this Problem? (family problem-solving and communication training), and Ways to Find Support (enhancing child and parent support networks) (see West et al., 2014).

Participants randomized to TAU received child and family-based therapy provided by a therapist in the General Child Psychiatry Clinic. TAU therapists (N=25) included pre- and post-doctoral psychology trainees, psychiatry fellows, and social work interns. They received a one-hour training on PBD prevalence, symptoms, course, and associated impairments, making this condition “enhanced” compared to typical TAU, and also received ongoing weekly supervision from licensed child-focused clinicians (including psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists) following routine clinic procedures. TAU supervisors identified their clinical orientation as follows: family systems (75%, n = 3); CBT (50%, n = 2), and behavioral/parent management (50%, n = 2); note that percentages exceed 100% given identification with multiple orientations in most cases. Though TAU and CFF-CBT sessions were matched for treatment dosage, TAU sessions were otherwise not manipulated in terms of content or structure; therapists and supervisors were instructed to follow their routine clinical practice for child/family-focused treatment.

Therapist fidelity to CFF-CBT was assessed via a fidelity checklist developed and piloted in the preliminary study (Pavuluri, Graczyk, et al., 2004), which asked raters to record the key CFF-CBT elements delivered in each treatment session (defined as number of elements delivered/total elements to be delivered × 100). Ten CFF-CBT participants were randomly selected, and a trained rater completed the fidelity checklist for audio recordings of all 12 CFF-CBT sessions for that participant. In addition, 10 TAU participants were randomly selected, and a trained rater completed the CFF-CBT fidelity checklist for all TAU sessions to assess for potential overlap with CFF-CBT ingredients. Study therapists demonstrated strong fidelity to the CFF-CBT manual (93% of content delivered), and there was minimal overlap with TAU (4% of CFF-CBT manual contents were delivered in TAU sessions) (West et al., 2014). Findings thus suggest that despite similar therapeutic orientation to CFF-CBT, TAU therapists did not deliver specific program elements of CFF-CBT.

All participants received medication management with non-study providers in the specialty mood disorders clinic following an evidence-based algorithm (Pavuluri, Henry, et al., 2004). Medication changes were tracked at each session but medication was not manipulated for the study. Medication changes during the course of the study did not differ between CFF-CBT (23%, n=15 reported a medication change during the course of the study) and TAU (23%, n=15), χ2 = .051, n=66, p=.82.

Diagnosis

The WASH-U-KSADS (Geller et al., 1996) is a semi-structured interview used to make a DSM-IV diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), including bipolar subtype (I, II, NOS) and most recent/current mood episode (mixed, manic, depressed). The WASH-U-KSADS was specifically designed to assess for bipolar disorder in youth with developmentally-specific symptoms of mania, depression, and mood episodicity. Research personnel were trained to administer the interview and demonstrated adequate reliability (kappa >.74).

Suicidal Ideation and Behavior

Current and lifetime suicidal ideation and behavior were assessed via the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2011), a semi-structured interview for ages six to elderly. Items assess the presence/absence of types of ideation (wish to die, non-specific active suicidal thoughts, thoughts with method or with intent, thoughts with plan and intent) occurring currently, in the lifetime, and since the prior assessment. Items also assess the presence/absence of suicidal behaviors currently, in the lifetime, and since the prior assessment, including an actual attempt (with potential for injury/harm); interrupted attempt (person is interrupted by an outside circumstance from starting the self-injurious act); aborted attempt (person begins to make an attempt, but stops him/herself before engaging in any self-destructive behavior); or preparatory behavior (acts or preparation towards an imminent attempt, e.g., writing a note, buying pills). In this study and past work (Weinstein, Van Meter, et al., 2015), we defined current ideation or behavior as occurring within the past month, as we believe this is proximal enough to the current state to signify current suicidality. For analyses examining change in the likelihood of any suicidal ideation across treatment, suicidal ideation is treated as dichotomous, with the presence of any type of ideation coded as “yes”. Additionally, suicide ideation intensity was assessed via the C-SSRS: five items assess the intensity of ideation (frequency, duration, controllability, deterrents, and reasons for suicidal thoughts) on 5-point scales, and ratings are summed to form the Suicide Ideation Intensity index. The C-SSRS has shown good sensitivity and specificity for suicidal thoughts and behavior across multiple studies (Posner et al., 2011); reliability in this sample was strong (α=.88).

Demographic Factors

Child age, sex, family income, and race/ethnicity were assessed via the Conners-March Developmental Questionnaire (Conners & March, 1996).

Analytic Approach

We first examined descriptive statistics by group in terms of treatment adherence and satisfaction, as well as in terms of suicidal ideation and behavior. The primary study question addressed whether CFF-CBT was associated with greater reduction in current suicidal ideation (SI) in comparison to TAU. We examined two separate current suicide ideation outcomes: (1) the likelihood (presence/absence) of SI and (2) the SI Intensity Index; exploratory analyses examined suicidal behaviors. To test our study question, we utilized a generalized linear mixed model testing a treatment (CFF-CBT vs. TAU) × wave (Baseline, Post-treatment, Follow-up) interaction, along with main effects for treatment and wave. The intercept was equal to the estimated likelihood of SI for TAU at baseline. As such, the main effect for treatment represented the average difference between TAU and CFF-CBT at baseline. This allowed us to confirm that there were no group differences in the outcome measures at baseline. We also examined possible group differences at post-treatment and follow-up by adjusting the intercept to those time points. The main effect for wave was equal to the average decrease in SI from baseline to follow-up, and the interaction effect was equal to the differential change in SI over time by treatment. We also modeled random intercepts, which tested whether SI differed across participants. Separate models were conducted for each outcome. For the dichotomous SI outcome we used a logit link function which modeled the changing likelihood over time in terms of suicidal thoughts. For SI intensity, we used a Poisson link function given the non-normal distribution, and we were primarily interested in estimating the changing degree of SI intensity over time by treatment. These models are an extension of linear mixed models given the focus on a dichotomous (any SI versus none) and non-normal positive integer (SI Intensity) outcome distributions. Models were tested in R 3.2.2 (R Development Core Team, 2014) using the RStudio IDE.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The intent-to-treat sample included 71 participants. The mean age of the sample was 9.17 years (SD = 1.60, range = 7–13 years); 41% (n = 29) were female. The sample was ethnically diverse: 54% were Caucasian, 30% were African American, 10% were Hispanic, 4% were American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1% were Native American or Pacific Islander, and another 1% were “Other”. The two conditions did not differ in age (t(69) = 0.31, p = .76), gender (χ2(1)= 0.68, p = .41), or ethnicity (χ2(5) = 5.18, p = .40). Sixty-two percent of the sample was diagnosed with Bipolar NOS (n = 44), 32% with Bipolar I (n = 23), and 6% with Bipolar II (n = 4). Index mood episodes included: 32% (n=22) mixed, 25% (n=17) manic, 23% (n=16) unspecified, 16% (n=11) depressed, and 4% (n=3) hypomanic. Comorbidity was prevalent in the sample: Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the most common comorbid disorder (n = 54; 79%), followed by oppositional defiant (ODD) (n = 25, 37%), anxiety (n = 24; 36%), and conduct disorders (n = 6; 9%). Baseline descriptive statistics and clinical characteristics for the sample, stratified by condition, are presented in Table 1. Findings indicated equivalence across conditions in terms of symptoms and functional impairment, demographics, and primary and comorbid diagnoses, with the exception of higher baseline child mania symptoms in TAU; this has been reported on previously (West et al., 2014).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Youth Assigned to CFF-CBT and Control.

| CFF-CBT (n = 35) |

Control (n = 36) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD |

| Age | 9.23 | 1.91 | 9.11 | 1.26 |

| Child Mania Rating Scale (CMRS)* | 19.80 | 8.46 | 26.63 | 11.07 |

| Children’s Depression Rating Scale | 42.37 | 12.30 | 40.66 | 10.50 |

| Clinical Global Impressions Scale-Severity | 4.06 | 0.67 | 4.17 | .51 |

| Current Ideation Intensity Index | 4.34 | 6.34 | 2.50 | 4.69 |

|

| ||||

| n | % | n | % | |

|

| ||||

| Female Sex | 16 | 46 | 13 | 36 |

| Family Income (<$50,000/year) | 15 | 43 | 14 | 39 |

| Living Situation (single-parent home) | 12 | 38 | 13 | 39 |

| Primary Diagnosis | ||||

| BD-I | 8 | 23 | 15 | 42 |

| BD-II | 2 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

| BD-NOS | 25 | 71 | 19 | 53 |

| Index episode (mixed) | 10 | 29 | 12 | 33 |

| Comorbid Anxiety | 12 | 38 | 12 | 34 |

| Comorbid Disruptive Behavior | 26 | 84 | 33 | 94 |

| Lifetime suicidal ideation | 20 | 57 | 18 | 50 |

| Current suicidal ideation | 16 | 46 | 12 | 33 |

| Lifetime suicidal behavior* | 8 | 23 | 17 | 47 |

| Current suicidal behavior | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

Note. Where data points were missing, percentages are calculated based on total number of available cases.

Denotes group differences, p < .05 on t-test or chi-square analyses.

CFF-CBT participants attended more core treatment sessions (M= 10.06, SD= 4.01) than TAU participants (M= 7.33, SD= 5.33), t(69) = 2.43, p= .02, and were significantly more likely to complete treatment than youth in TAU, χ2(1) = 5.63, p= .02. By 6-month follow up, there were no significant differences in attrition by treatment (nCFF-CBT = 19, nTAU = 16 χ2(1) = 0.69, p= .41). Satisfaction with treatment for CFF-CBT was high (M=2.92 out of 3.0) on a parent-report satisfaction measure, and marginally higher than for TAU (M=2.65), t(39) = 1.91, p= .06.

Baseline Prevalence of Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors

Suicidal ideation was prevalent at baseline. Among the full sample, 53.5% (n=38) of youth reported lifetime suicidal ideation and 39.4% (n=28) reported current ideation; 23.9% (n=17) reported a history of severe ideation (i.e., active ideation with method and/or plan and intent); and 14.1% (n=10) endorsed current severe ideation. A substantial number of youth (35.2%; n=25) reported a history of suicidal behaviors (including preparatory behaviors, interrupted/aborted or actual attempts); fewer youth reported current behaviors (2.8%; n=2) at baseline and no youth reported current behaviors at post-treatment or follow-up. Thus, the low frequency of suicidal behaviors precluded longitudinal analyses for these outcomes. Table 1 also displays rates of lifetime suicidal ideation, current suicidal ideation, current ideation intensity, lifetime suicidal behaviors, and current suicidal behaviors at baseline by treatment condition. There were no significant differences between treatment conditions at baseline, with the exception of lifetime suicidal behaviors: significantly higher numbers of youth in TAU reported a history of any form of suicidal behaviors versus those in CFF-CBT (χ2(1) = 4.68, p= .03). However, examination of each type of behavior indicated no significant differences by treatment condition: lifetime attempts nCFF-CBT = 2, nTAU = 5; interrupted or aborted attempts nCFF-CBT = 7, nTAU = 11; or preparatory behaviors nCFF-CBT = 3, nTAU = 4 (of note, some youth endorsed multiple behaviors). There were no other significant differences in suicide variables by treatment at baseline.

Suicidal Ideation Treatment Outcomes

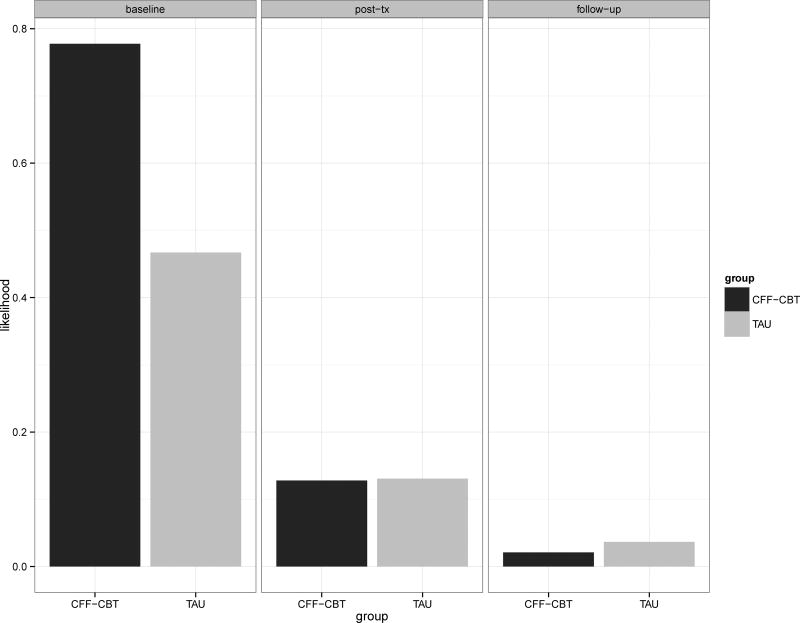

Models examining trajectories of SI likelihood revealed a significant fixed effect for wave (λ = −1.27, p= .03), indicating that the risk of SI was reduced by approximately 72% per wave on average (across both conditions) (OR = 0.28, 95% Confidence Interval = [0.06, 0.76]). However, effects of treatment (λ = 0.51, p= .30; OR = 1.66, 95% CI = [0.64, 4.79]), and the treatment by wave interaction (λ = −0.53, p = .53) were not significant. These findings suggested that there was no difference in baseline SI likelihood by treatment condition, and no difference in the reduction of SI over time by treatment. In addition, we also adjusted the intercept to test possible group differences at later waves, and we found no differences in the likelihood of SI between conditions at post-treatment (λ = −.001, p = .998) or follow-up (λ = −.52, p = .74). Figure 1 displays the estimated likelihood of SI over time by treatment, and the rates of current SI by treatment over time are presented in Table 2. As the figure illustrates, all youth improve in their SI.

Figure 1.

Estimated likelihood of suicidal ideation over time as a function of treatment condition. CFF-CBT=Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; TAU=Treatment as Usual; Post-tx= Post-treatment (12 weeks); Follow-up = 6 month follow-up.

Table 2.

Current Suicide Ideation Rates and Intensity by Treatment over Time.

| Baseline | Post-Tx (12 wks) |

Follow-Up (6 mo) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI Presence | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| CFF-CBT | 16 | 46 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| TAU | 12 | 33 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| SI Intensity | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| CFF-CBT | 4.34 | 6.34 | 0.88 | 3.17 | 1.83 | 3.38 |

| TAU | 2.50 | 4.69 | 0.56 | 2.36 | 1.53 | 3.18 |

Models examining SI intensity revealed a significant fixed effect for wave (λ = −0.59, p < .001; RR = 0.55, 95% CI= [0.42, 0.71]). This signified that the intensity of SI decreased by approximately 45% per wave across treatment condition. Changes over time are shown in Figure 2, which displays the percentage of youth reporting varying levels of SI intensity over time by treatment. Given the nonnormal distribution and the high percentage of youth not experiencing any SI (as youth without SI achieve a score of 0 on the Intensity scale), the full range of SI intensity scores are displayed (see Figure 2) rather than presenting the means at each time point (for means/SDs over time, see Table 2). We did not find significant effects for condition (λ =1.39, p = .15) or the treatment by wave interaction (λ = −.21, p = .21), which suggested that there was no difference in baseline SI intensity or rate of SI intensity reduction over time by treatment. We also found no differences by condition in SI intensity at post-treatment (λ = 1.18, p = .23) or follow-up (λ = 0.96, p = .34). Of note, there was a slight increase in ideation intensity among all youth from post-treatment to follow-up.

Figure 2.

Suicidal ideation intensity scores over time by treatment condition. SI intensity = Suicidal Ideation Intensity index; CFF-CBT=Child- and Family-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; TAU=Treatment as Usual; Post-tx= Post-treatment (12 weeks); Follow-up = 6 month follow-up; Count = number of youth.

Discussion

This was the first study to examine suicidality response to psychosocial intervention in a randomized clinical trial of children and preadolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. We hypothesized that CFF-CBT would generalize to the treatment of suicidality, given that the core treatment components aim to address key family, cognitive, and affective risk factors for suicide. Findings indicated that suicidal ideation was significantly reduced for all youth across treatment. Contrary to hypotheses, however, between-group differences in treatment response trajectories for any ideation and ideation intensity were not significant. These findings must be viewed in the context of symptom outcomes: whereas youth in CFF-CBT experienced significantly greater change in mania and depression symptoms across treatment versus TAU, with youth in TAU remaining symptomatic at follow-up (West et al., 2015), all youth responded similarly to treatment in terms of their SI improvement.

The present findings underscore the importance of assessing and addressing suicidality in preadolescent youth with bipolar disorder, with prevalence rates indicating that nearly half the sample experienced current ideation pre-treatment. Encouragingly, all youth improved across treatment, suggesting that early intervention for even this high-risk group may substantially reduce suicidal ideation. The lack of treatment effects, although contrary to our hypotheses, is largely consistent with the extant literature: numerous studies of psychosocial treatments for adolescent suicidal ideation and behavior, across a range of therapeutic orientations, report similar results (e.g., Asarnow et al., 2011; Brent et al, 2009; Donaldson et al., 2005; Green et al., 2011; Harrington et al., 1998; Ougrin et al., 2013; Rudd et al., 1996). In light of such findings, recent reviews of the literature on suicide interventions for adolescents have suggested that specialized treatment for suicidal youth may not offer benefit over usual care when examining suicidal ideation or behavior outcomes (Asarnow et al., 2011; Corcoran, Dattalo, Crowley, Brown, & Grindle, 2011). However, there are certainly exceptions, and consideration of past RCTs with promising findings offers insight into the present results, as detailed below.

Several factors may have contributed to our findings. The present study included a sample participating in an RCT for PBD, rather than selected for suicidality; this sampling issue may have limited our ability to detect significant group differences in suicidal thoughts despite significant treatment differences found at the PBD symptom level (West et al., 2014). Alternately, it is possible that both treatments in the current study were sufficient for reducing SI, despite CFF-CBT outperforming TAU in terms of PBD symptom response. Treatment-as-usual was a dose-matched family-based treatment provided by clinicians in a competitive academic medical center that is committed to evidence-based treatment methods, with high satisfaction ratings from families. Youth in TAU also attended more sessions than is typical of community treatment for suicidal youth (e.g., four or fewer sessions; Spirito et al., 2002). Whereas TAU was not specialized for or specific to the unique characteristics of youth and families affected by PBD (i.e., which likely contributed to group differences on symptom outcomes), the provision of a non-programmatic but high quality, well-received, supervised treatment may nonetheless be relevant for the treatment of pediatric SI at this stage of severity in the continuum of suicidality.

Across the youth suicide intervention literature, treatments that have shown promise for decreasing suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents share several common elements, including improving family and other relationships, parenting skills, and individual coping skills (Glenn et al., 2015). Studies with the strongest treatment effects on suicidal outcomes have targeted the family system, thus supporting the importance of family-based treatment methods for suicide prevention (e.g., Attachment Based Family Therapy (ABFT; Diamond et al., 2010); Resourceful Adolescent Parent Program (RAP-P; Pineda and Dadds, 2013); Mentalization Based Treatment (MBT-A; Rossouw and Fonagy, 2012)). Further, two successful intervention studies found that improvement in family functioning (Pineda and Dadds, 2013) and family attachment (Rossouw and Fonagy, 2012) mediated treatment change in suicidal thoughts and behaviors. These identified effective elements are incorporated in CFF-CBT in the context of addressing the core impairments associated with PBD (e.g., “O”: family communication and problem-solving; “B”: balanced lifestyle for parents; “I”: parent self-efficacy).

A focus on overall family/parent functioning was likely also present in TAU given that 3/4 TAU supervisors endorsed a family systems approach, and 2/4 endorsed a behavioral/parent management orientation. In many TAU cases there may have also been significant attention to common CBT elements (even if not specific to PBD) given that 2/4 clinicians endorsed a CBT orientation. Limited information on specific content of TAU sessions precludes analyses of specific treatment elements across conditions, and thus interpretations are made very cautiously. However, involvement of the parents and family, and a common focus on CBT elements across both conditions may contribute to the lack of group differences. Indeed, in RCTs that found significant between-group differences, the control condition is typically a community control that does not include a substantial family component: Pineda and Dadds (2013) compared parent-focused RAP-P to routine care, where family intervention was limited to crisis management and safety planning but otherwise excluded; Diamond and colleagues (2011) compared their family treatment (ABFT) to facilitated community referral, which primarily consisted of individual, group, or no therapy with only two youth receiving family therapy. Huey et al. (2004); compared the family-intensive multi-systemic therapy (MST) to inpatient hospitalization; and family/parent sessions were significantly fewer in the community treatment control of Esposito-Smythers and colleagues’ (2011) examination of Integrated-CBT. As such, the quality and quantity of a family-based TAU in the present study differs from past work, and it may be that the lack of a condition by time interaction can be explained by having a fairly strong active treatment comparison condition. Our results parallel those of Donaldson and colleagues (2005), who observed improvements in suicidal ideation across conditions in their comparison of two high-integrity, high-attendance treatments.

The influence of regression to the mean must also be considered. In their review of 29 intervention studies for youth suicidality, Glenn and colleagues (2015) noted that suicidal thoughts and behaviors tend to dramatically decrease over time even in the absence of intervention. Thus, it is possible that reductions in suicidal ideation in the present study were unrelated to treatment and rather reflects the natural decline with time. However, given that suicidal ideation intensity did increase slightly from post-treatment to follow-up suggests changes in suicidality were related to the active treatment phase rather than solely regression to the mean.

Importantly, neither treatment in this study eradicated suicidal thoughts completely. Results thus suggest room for improvement, and interventions that are specific to the treatment of suicidality may achieve greatest efficacy. Psychosocial treatments that have shown greater efficacy for suicidal thoughts or behaviors versus control were specifically designed to treat suicidality and related risk factors (e.g., Diamond et al., 2010 ; Esposito-Smythers et al., 2011; Pineda and Dadds, 2013; Rossouw and Fonagy, 2012). A review of studies examining suicidal individuals demonstrated that interventions targeting amelioration in illness symptoms only do not result in concurrent reduction in suicide risk (Goldstein, 2009), which is consistent with our pattern of findings indicating greater symptom improvement in CFF-CBT versus TAU (West et al., 2014) in the absence of significant group differences in suicide outcomes. As such, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) guidelines for PBD state that psychosocial treatments that specifically target the management of suicidality may be indicated (Kowatch et al., 2005). Thus, an expanded focus on the elements related to suicide risk, including family communication of suicidal events, child self-esteem, and skill-building around responding to suicidal thoughts specifically, may optimize CFF-CBT for suicide prevention while also preserving the focus on underlying PBD symptoms and associated difficulties.

Strengths of this study included the focus on a younger sample than previously examined for suicide-related outcomes in an RCT; examination of a complex, diverse, and primarily low SES sample; the use of a clinician-interview measure of suicidal thoughts and behaviors, rather than youth or parent-report; and the comparison to an enhanced treatment control. However, results must be viewed in the context of study limitations. A primary limitation was the lack of power. The sample was drawn from an RCT focused on the treatment of PBD, rather than selected specifically for suicidality, and thus the study was not powered for examining lower frequency suicidal events such as thoughts and, especially, behaviors. The small numbers of suicidal behaviors in this study prohibited examination of differential change across treatment, but suicidal behavior is highly predictive of completed suicide (Bridge et al., 2006) and essential to examine in future research with much larger samples that are adequately powered to examine suicidal outcomes. Related, given the young age of the sample, we chose to be as inclusive as possible in our analyses and thus focused on the full range of suicidal thoughts rather than only examining more severe forms of ideation; however, future work must examine treatment-related changes in severe thoughts. Moreover, given that this was an outpatient treatment study, findings may not generalize to more severe clinical populations or youth presenting for emergency treatment. Further, youth in TAU exhibited significantly higher lifetime suicidal behaviors and greater parent-reported mania than youth in CFF-CBT. Although analyses did not examine these variables, it still indicates that the two groups were not entirely equivalent in terms of clinical characteristics at baseline. Additionally, incomplete information on the content delivered in TAU (i.e., beyond the presence of specific CFF-CBT content) limited our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding shared interventions related to suicidality. Another limitation pertains to medication use; although medication changes were captured in the measurement plan and did not differ by condition, it is possible that unmeasured medication effects might explain treatment improvement for some study participants. Last, a longer follow-up period may elucidate treatment-related differences in suicidal thoughts that did not emerge within the present timeframe.

In sum, results offer important clinical implications and avenues for future research. Findings are promising that youth with bipolar spectrum disorders who have an early onset (e.g., age 7–13) of suicidal ideation may experience improvement in suicidal thoughts with child- and family-based treatment, even when provided by clinicians that are not specialized in pediatric mood disorders. Future research that aims to examine treatment-related change in suicidal thoughts and behaviors, as well as the potential mechanisms underlying improvement, in well-powered samples will be necessary to understand how best to meet the needs of this high-risk population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Young Investigator Award YIG-1-140-11 from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (S.M.W.) and the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) K23 grant MH079935 (A.E.W.)

References

- Algorta GP, Youngstrom EA, Frazier TW, Freeman AJ, Youngstrom JK, Findling RL. Suicidality in pediatric bipolar disorder: predictor or outcome of family processes and mixed mood presentation? Bipolar disorders. 2011;13(1):76–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman E, Hedeker D, Peterson JL, Davis JM. A comparative evaluation of three self-rating scales for acute mania. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50(6):468–471. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders. 4. Washington DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Baraff LJ, Berk M, Grob CS, Devich-Navarro M, Suddath R, Tang L. An emergency department intervention for linking pediatric suicidal patients to follow-up mental health treatment. Psychiatric services. 2011;62(11):1303–1309. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bhangoo RK, Dell ML, Towbin K, Myers FS, Lowe CH, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Clinical correlates of episodicity in juvenile mania. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2003;13(4):507–514. doi: 10.1089/104454603322724896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Greenhill LL, Compton S, Emslie G, Wells K, Walkup JT, Posner K. The Treatment of Adolescent Suicide Attempters study (TASA): predictors of suicidal events in an open treatment trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(10):987–996. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b5dbe4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, McMakin DL, Kennard BD, Goldstein TR, Mayes TL, Douaihy AB. Protecting adolescents from self-harm: a critical review of intervention studies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(12):1260–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Baugher M. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA. Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(3 – 4):372–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners C, March J. The Conners/March Developmental Questionnaire. Toronto, ON: MultiHealth Systems Inc; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J, Dattalo P, Crowley M, Brown E, Grindle L. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for suicidal adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(11):2112–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, Levy S. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(2):122–131. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson D, Spirito A, Esposito-Smythers C. Treatment for adolescents following a suicide attempt: Results of a pilot trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(2):113–120. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito C, Spirito A, Boergers J, Donaldson D. Affective, behavioral, and cognitive functioning in adolescents with multiple suicide attempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33(4):389–399. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.4.389.25231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito-Smythers C, Spirito A, Kahler CW, Hunt J, Monti P. Treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and suicidality among adolescents: a randomized trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2011;79(6):728. doi: 10.1037/a0026074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller B, Williams M, Zimerman B, Frazier J. Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) St Louis, MO: Washington University; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn CR, Franklin JC, Nock MK. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44(1):1–29. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.945211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR. Suicidality in pediatric bipolar disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18(2):339–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Gill MK, Esposito-Smythers C, Keller M. Family environment and suicidal ideation among bipolar youth. Archives of suicide research. 2009;13(4):378–388. doi: 10.1080/13811110903266699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Fersch-Podrat RK, Rivera M, Axelson DA, Merranko J, Yu H, Birmaher B. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: results from a pilot randomized trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2015;25(2):140–149. doi: 10.1089/cap.2013.0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein TR, Ha W, Axelson DA, Goldstein BI, Liao F, Gill MK, Hower H. Predictors of prospectively examined suicide attempts among youth with bipolar disorder. Archives of general psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1113–1122. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, Wood A, Kerfoot M, Trainor G, Roberts C, Rothwell J, Byford S. Group therapy for adolescents with repeated self harm: randomised controlled trial with economic evaluation. BMJ. 2011;342:d682. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R, Kerfoot M, Dyer E, McNIVEN F, Gill J, Harrington V, Byford S. Randomized trial of a home-based family intervention for children who have deliberately poisoned themselves. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(5):512–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Henggeler SW, Rowland MD, Halliday-Boykins CA, Cunningham PB, Pickrel SG, Edwards J. Multisystemic therapy effects on attempted suicide by youths presenting psychiatric emergencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(2):183–190. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolin EM, Weller EB, Weller RA. Suicide risk factors in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Current psychiatry reports. 2007;9(2):122–128. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0081-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test–Second Edition (KBIT-2) Circle Pines. MN: American Guidance Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Keenan-Miller D, Peris T, Axelson D, Kowatch RA, Miklowitz DJ. Family functioning, social impairment, and symptoms among adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):1085–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowatch RA, Fristad M, Birmaher B, Wagner KD, Findling RL, Hellander M. Treatment guidelines for children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(3):213–235. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1996;3(1):25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Klein DN. Bipolar disorders during adolescence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2003;108(s418):47–50. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s418.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, Williams D. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(2):98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ougrin D, Boege I, Stahl D, Banarsee R, Taylor E. Randomised controlled trial of therapeutic assessment versus usual assessment in adolescents with self-harm: 2-year follow-up. Archives of disease in childhood. 2013 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303200. archdischild-2012-303200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Graczyk PA, Henry DB, Carbray JA, Heidenreich J, Miklowitz DJ. Child-and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: development and preliminary results. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):528–537. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Henry DB, Devineni B, Carbray JA, Naylor MW, Janicak PG. A pharmacotherapy algorithm for stabilization and maintenance of pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(7):859–867. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128790.87945.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda J, Dadds MR. Family intervention for adolescents with suicidal behavior: a randomized controlled trial and mediation analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):851–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children's depression rating scale. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1984;23(2):191–197. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. Retrieved from http://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Raison CL, Capuron L, Miller AH. Cytokines sing the blues: inflammation and the pathogenesis of depression. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(1):24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlledtrial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1304–1313. e1303. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Rajab MH, Orman DT, Stulman DA, Joiner T, Dixon W. Effectiveness of an outpatient intervention targeting suicidal young adults: preliminary results. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1996;64(1):179. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel LS, West AE, Harral EM, Patel NB, Pavuluri MN. Parent–child interactions in pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of clinical psychology. 2008;64(4):422–437. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A, Stanton C, Donaldson D, Boergers J. Treatment-as-usual for adolescent suicide attempters: Implications for the choice of comparison groups in psychotherapy research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(1):41–47. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbaniak GC, Plous S. Research randomizer, version 3.0. 1997 Retrieved from Available at: http://www.randomizer.org/about.htm.

- Weinstein SM, Henry DB, Katz AC, Peters AT, West AE. Treatment moderators of child-and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;54(2):116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein SM, Van Meter A, Katz AC, Peters AT, West AE. Cognitive and family correlates of current suicidal ideation in children with bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2015;173:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Pavuluri MN. Psychosocial treatments for childhood and adolescent bipolar disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2009;18(2):471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Weinstein SM, Peters AT, Katz AC, Henry DB, Cruz RA, Pavuluri MN. Child-and family-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for pediatric bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53(11):1168–1178. e1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]