Abstract

Chiral molecular recognition is important to biology, separation, and asymmetric catalysis. Because there is no direct correlation between the chiralities of the host and the guest, it is difficult to design a molecular receptor for a chiral guest in a rational manner. By cross-linking surfactant micelles containing chiral template molecules, we obtained chiral nanoparticle receptors for a number of 4-hydroxyproline derivatives. Molecular imprinting allowed us to transfer the chiral information directly from the guest to host, making the molecular recognition between the two highly predictable. Hydrophobic interactions between the host and the guest contributed strongly to the enantio- and diastereoselective differentiation of these compounds in water, whereas ion-pair interactions, which happened near the surface of the micelle, were less discriminating. The chiral recognition could be modulated by turning the size and shape of the binding pockets.

Introduction

Biomacromolecules such as proteins have exceptional abilities to differentiate stereoisomers, whether in binding, transport, or catalysis. Over the last decades, chemists have developed many effective strategies for the synthesis of chiral molecules. Although a properly functionalized chiral host has many potential applications, their rational design is not straightforward.

One challenge is related to size: because a guest-encompassing host is larger than the guest itself, its synthesis inevitably involves more atoms and bonds. Another challenge, possibly a more fundamental one, is related to how chiral host and guest molecules interact with each other. For example, chemists can synthesize chiral receptors easily from chiral building blocks. However, since there is no direct correlation between the chiralities of the host and the guest, their molecular recognition is difficult to predict.1–3 Likewise, chiral stationary phases are frequently used to separate enantiomers, but predicting the order of elution a piori is difficult.

Molecularly imprinted receptors are advantageous in this regards.4–15 In the most traditional embodiment of molecular imprinting, free radical polymerization is induced in a mixture of template molecules, functional monomers (FMs), porogenic solvents, and cross-linkers such as divinylbenzene (DVB) or ethylene glycol dimetharylate (EGDMA). The FMs can interact with the templates by noncovalent interactions or, alternatively, form reversible bonds with the templates. A large amount of cross-linkers are used to maintain rigidity of the resulting molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP). Once the templates are removed by washing or bond cleavage, the cross-linked material is left with cavities complementary to the templates in size, shape, and distribution of functional groups.

MIPs have many uses including in molecular recognition, separation, enzyme-mimetic catalysis, and chemical sensing.4–15 One of the earliest applications of MIPs was as the stationary phase in the chiral separation of molecules.16, 17 Because the binding sites in an imprinted material are created by polymerization/cross-linking around the templates, the chiralities of the MIP host and guest in principle are directly correlated, making their interactions predictable.

Despite the great potential of MIPs as functional materials, they face some difficult challenges. Their binding sites tend to be heterogeneous and poorly defined in structure.4–6, 8–10, 12, 13, 18, 19 Conventional MIPs are intractable macroporous polymers and it is difficult to study their structure and binding by spectroscopic or calorimetric methods.11 Template molecules are often trapped inside the highly cross-linked polymer and difficult to be removed. Although soluble nanoparticle MIPs have been reported in the literature,20–28 aqueous compatibility remains an issue,29 as most FMs bind their guests by polar interactions that are weakened significantly by water molecules.

We recently used molecular imprinting to create hydrophobic binding sites within cross-linked micelles.30 Binding is driven by the hydrophobic interactions between the MINP and guest; binding selectivity mainly comes from the shape/size complementarity between the two. Although the micelles are highly cross-linked, because polymerization and cross-linking are confined within the micellar boundary, MINPs are fully soluble in water due to their hydrophobic/hydrophilic core–shell morphology and nanodimension (4–5 nm). Using this technique, we have created strong and selective receptors for a number of different guests including bile salt derivatives,30 aromatic carboxylates and sulfonates,31–33 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),34 carbohydrates,35, 36 and oligopeptides.37

In this work, we studied how the transfer of chirality from a template to its imprinted MINP host influenced the chiral recognition. The transfer was found to be reliable and the chiral recognition highly predictable not only for the templates but also for their analogues. Within a series of guest molecules, the relative binding order could be maintained while the binding affinity varied by a large degree—a feature potentially highly useful in chromatographic separations.1–3

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of the MINPs is shown in Scheme 1. Typically, the template molecules were first solubilized in water by micelles of cross-linkable surfactant 1. The template is often hydrophobic overall, but contains a polar group (shown by the magenta-colored sphere). Surface-cross-linking of the micelle was achieved using diazide 2 by the Cu(I)-catalyzed click reaction.38–40 The surface-cross-linked micelle (SCM) had residual alkynyl groups on the surface because the cross-linkable surfactant has three alkynes and the cross-linker two azides—the ratio between the two was 1:1.2 in typical MINP preparation.

Scheme 1.

Preparation of MINP by surface–core double cross-linking of template-containing micelle of 1.

Hydrophilic ligands were then installed on the surface of the SCMs by another round of click reaction using glucose-derived ligand 3. The micelle also contained 1 equiv divinylbenzene (DVB) and a small amount of 2, 2-dimethoxy- 2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA), as the cross-linker and photoinitiator for the core-cross-linking, respectively. A high level of DVB was needed for the rigidity of the nanoparticle and shown to be important to binding selectivity.30 After the surface-cross-linking and functionalization, free radical polymerization was initiated photochemically to cross-link the core. Once the template was removed by repeated solvent washing, the MINP contained a binding pocket complementary to the template.

The MINPs were characterized following previously reported procedures.30–32, 34 For example, 1H NMR allowed us to monitor the surface- and core-cross-linking (ESI). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) afforded the size of the nanoparticles, as well as their average molecular weights. The DLS size was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy previously for similar cross-linked micelles.38 The surface-cross-linking was also verified by mass spectrometry after the 1,2-diol in the cross-linked 2 was cleaved.38

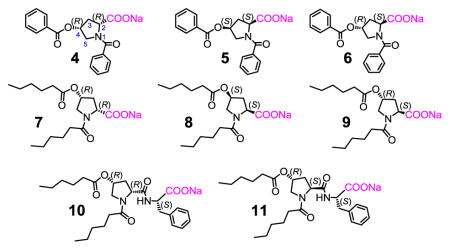

To understand how chiral MINPs and guests interact with one another, we chose several 4-hydroxyproline derivatives (4–9) as the model compounds in this study. One reason for their choice is the biological importance: 4-hydroxyproline is a major component of collagen,41 and both the hydroxyl and its stereochemistry are critical to the stability of the triple helical structure of the protein.42, 43 The commercial availability of their stereoisomers allowed us to quickly access the derivatives needed for the study. As an amino acid derivative, these compounds also enabled us to understand their chiral recognition in the context of peptides, an extremely important topic in supramolecular and bioorganic chemistry.44–56

The 4-hydroxyproline derivatives are acylated at the secondary amine and the 4-hydroxyl to enhance their hydrophobicity. Their syntheses are reported in the Experimental Section. Among these guest molecules, compounds 4 and 5 are enantiomers. Compound 6 differs from 4 in the configuration of C2 and is a diastereomer of 4 and 5. Compounds 7–9 are essentially the aliphatic versions of 4–6, having the same stereochemical configurations. Compounds 10 and 11 are essentially 7 and 9, respectively, with an additional phenylalanine coupled.

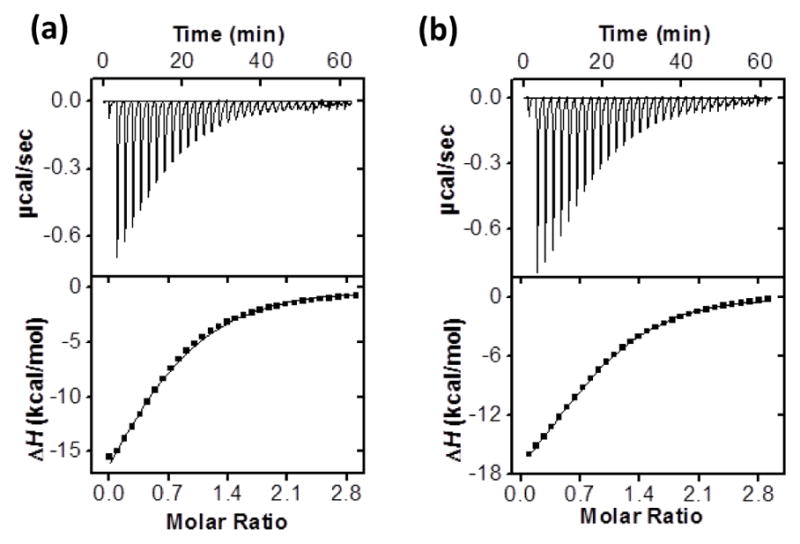

Chiral molecular recognition between the MINPs and the guests was studied by ITC, one of the most widely used methods to study intermolecular interactions.57 By measuring the heat change during the titration, ITC affords a wealth of information on the binding, e.g., the binding constant (Ka), enthalpy (ΔH), and the number of binding sites per particle (N). We have confirmed in many studies that binding constants obtained by ITC agreed with those by other methods such as fluorescence titration.30–34

Figure 1 shows two typical ITC titration curves, for the binding between MINP(4), i.e., MINP prepared with 4 as the template, and its template. We performed the titration in both water (Figure 1a) and 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). The two bindings showed very similar binding constants (Ka = 3.7–4.0 × 105 M−1) with a negative/favorable enthalpy. The binding constant is equivalent to 7.6 kcal/mol of binding free energy (−ΔG). The average number of binding site per nanoparticle (N) was 0.8–1.0.

Fig 1.

ITC titration curves obtained at 298 K for the binding of (a) 4 (0.12 mM) by MINP(4) (0.01 mM ) in Millipore water, and (b) 4 (0.12 mM) by MINP(4) (0.01 mM) in 50 mM Tris buffer pH 7.4. The data correspond to entries 1 and 2, respectively, in Table 1. Additional ITC titration curves can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI).

Table 1 summarizes the ITC binding data. The majority of the bindings were measured in water, as the binding constants by MINP(4) for 4 were quite similar in water and in Tris buffer. In addition to the binding parameters, we listed Krel, the binding constant of a guest relative to that of the template. This value can be regarded as the selectivity in the chiral recognition.

Table 1.

Binding data for MINPs obtained by ITC.a

| Entry | Host | Guest | Ka (104 M−1) | Krel | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔS (kcal/mol) | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MINP-4 | 4 | 37.1 ± 5.2 | 1 | −7.59 | −19.84 ± 0.28 | −12.25 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | MINP-4 | 4 | 39.7 ± 0.3b | - | −7.63 | −23.64 ± 0.99 | −16.01 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | MINP-4 | 5 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 0.019 | −5.27 | −0.68 ± 0.06 | 4.59 | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | MINP-4 | 6 | 17.2 ± 2.5 | 0.46 | −7.14 | −17.07 ± 2.58 | −9.93 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | MINP-4 | 7 | 4.15 ± 0.19 | 0.11 | −6.30 | −3.51 ± 0.45 | 2.79 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| 6 | MINP-4 | 8 | 1.04 ± 0.35 | 0.027 | −5.48 | −1.29 ± 0.77 | 4.19 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 7 | MINP-4 | 9 | 1.94 ± 0.67 | 0.05 | −5.84 | −1.83 ± 0.78 | 4.01 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | MINP-6 | 4 | 21.5 ± 2.1 | 0.61 | −7.27 | −19.88 ± 2.38 | −12.61 | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| 9 | MINP-6 | 5 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 0.025 | −5.40 | −0.78 ± 0.08 | 4.62 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 10 | MINP-6 | 6 | 35.8 ± 4.9 | 1 | −7.57 | −18.38 ± 1.05 | −10.81 | 1.0 ± 0.1 |

| 11 | MINP-6 | 7 | 1.65 ± 0.09 | 0.047 | −5.75 | −1.57 ± 0.21 | 4.18 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| 12 | MINP-6 | 8 | 1.45 ± 0.52 | 0.041 | −5.67 | −1.33 ± 0.48 | 4.34 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 13 | MINP-6 | 9 | 3.19 ± 0.47 | 0.089 | −6.14 | −2.16 ± 0.84 | 3.98 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 14 | MINP-7 | 4 | -c | 0 | -c | -c | -c | -c |

| 15 | MINP-7 | 5 | -c | 0 | -c | -c | -c | -c |

| 16 | MINP-7 | 6 | -c | 0 | -c | -c | -c | -c |

| 17 | MINP-7 | 7 | 17.98 ± 2.05 | 1 | −7.16 | −19.04 ± 4.48 | −11.88 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 18 | MINP-7 | 8 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | 0.044 | −5.34 | −0.78 ± 0.03 | 4.56 | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| 19 | MINP-7 | 9 | 9.83 ± 0.17 | 0.54 | −6.81 | −8.29 ± 0.96 | −1.48 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| 20 | MINP-10 | 10 | 421 ± 25 | 1 | −9.03 | −9.74 ± 1.22 | −20.71 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 21 | MINP-10 | 11 | 7.24 ± 0.1 | 0.017 | −6.62 | −13.93 ± 2.36 | −7.31 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

The titrations were generally performed in duplicates in Millipore water unless otherwise indicated and the errors between the runs were <10%.

Titration was carried out in 50 mM Tris buffer pH = 7.4.

Binding was extremely weak (Ka < 50 M−1).

Our binding data show that MINP(4) had an excellent enantioselectivity, with Krel = 0.019 for 5 but only a modest diastereoselectivity, with Krel = 0.46 for 6 (entries 3 and 4). A chiral host is commonly believed to need at least a three-point interaction with the guest to effectively differentiate enantiomers.58–60 The excellent enantioselectivity of MINP(4) suggests that the condition was fully met in our binding. Because the binding took place in water, hydrophobic interactions have been shown to dominate the binding of MINPs according to our recent studies.30–32, 34 For compounds 4 and 5, the two benzoyl groups are obvious points of interactions as a result of hydrophobic imprinting. The third interaction, most likely, comes from the carboxylate, which could ion-pair with a nearby ammonium headgroup of the cross-linked 1.

Many of our templates in MINP preparation contain an anionic polar group (sulfonate or carboxylate).30–32, 34 There are two considerations for the choice. First, the incorporation of a hydrophobic anionic template into the cationic micelle of 1 is favored by both electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions. A stronger interaction between the template and the micelle should be helpful to both the imprinting and the guest-rebinding. Second, the anionic group needs to ion-pair with the surfactant headgroup and thus must stay on the surface of the micelle. The ion-pairing interaction serves to anchor the template on the micellar surface and facilitates the template removal, as revealed by fluorescence spectroscopy in an earlier publication.30

The poor diastereoselectivity of MINP(4) suggests that the ion-pair, if being one of the main interactions to determine the enantioselectivity, has a much larger tolerance of error than the hydrophobic interaction with the benzoyl. This is evident from the selectivity of both MINP(4) and MINP(6). Anytime when the benzoyl at C4 position was inverted—e.g., from 4 to 5 or from 6 to 5—excellent selectivity was obtained. But anytime when the carboxylate was inverted—e.g., from 4 to 6 or vice versa—poor selectivity was obtained.

The different tolerances for error by the carboxylate and benzoyl groups most likely are derived from their different depths in the cross-linked micelle. The carboxylate is expected to reside on the surface of micelle. Even if it prefers to ion-pair with a particular ammonium, the preference must be weak, as there are numerous other ammoniums near this particular ammonium group. The benzoyl group, on the other hand, is expected to insert itself into a hydrophobic pocket in the core of the micelle, formed as a result of the hydrophobically based molecular imprinting. An inverted benzoyl on the guest should not fit into the pocket imprinted for the original one.

We also listed the binding enthalpies (ΔH) and entropies (TΔS) in Table 1. Our data show that the MINP binding was always favored enthalpically, with negative ΔH values. One might think the negative ΔH contradicts hydrophobic interactions as the main driving force, as classical hydrophobic effective is considered entropically driven, at least at low temperatures.61 However, the effect is now considered multifaceted and the energetic characteristics may be different depending on the (aliphatic/aromatic) nature of the guests and the size/shape of the hydrophobic surfaces.62–68 In addition, because electrostatic interactions also contribute to the binding and they can be either enthalpically or entropically favored,69–73 the overall picture is rather complicated.

According to Table 1, whenever the binding was strong (e.g., in the case of the template by its own MINP or the poorly distinguished diastereomers), a large negative (unfavorable) entropic term (TΔS) was observed, compensated by an even larger negative (favorable) enthalpy. Thus, for best-fitted guests, the binding was usually driven enthalpically. The results are reasonable, as binding between a highly complementary hots–guest pair is expected to restrict their freedom significantly. In contrast, for the poorly fitted guests—i.e., those with relatively low binding affinities, including the linear 7–9 by MINP(4) or MINP(6)—there was a significant positive/favorable entropy that contributed to the binding.

We likewise examined the enantio- and diastereoselectivity of MINP(4) and MINP(6) for compounds 7–9, the aliphatic analogues of 4–6. The two MINPs basically showed the same trend. For example, among the three (aliphatic) guests, MINP(4) bound 7 the most strongly, with Ka = 4.2 × 104 M−1 (entry 7). The substantial binding affinity suggests that the linear aliphatic chain could fold and insert itself into the pocket created for the benzoyl (Figure 2, top panel). Although burying the hexanoyl group in the hydrophobic pockets has a significant hydrophobic driving force, the folding is expected to weaken the binding, by nearly 1 order of magnitude shown by our data.

Fig 2.

Schematic comparison of binding selectivity of MINP(4) and MINP(7).

The binding constant of the aliphatic guests by MINP(4) followed the order of 7 > 9 > 8, thus paralleling the order displayed by the aromatic guests (4 > 5 > 6). This is a significant result because it suggests that the relative selectivities in the original (aromatic) series were maintained in their (aliphatic) analogues, likely because similar binding mechanisms and driving forces were involved. Meanwhile, both the absolute binding constants and the extent of selectivity decreased in the aliphatic series, shown by the different ratios of Ka for 4/5 (>50) and 7/8 (ca. 4). The results were reasonable, as the MINP was created specifically for 4, an aromatic guest, and should be most selective for the original template.

Not surprisingly, MINP(7) preferred template 7 over its diastereomer (9), which was preferred over its enantiomer (8). This is exactly the same order of binding found in MINP(4) for the benzoyl derivatives. Meanwhile, however, none of the aromatic guests (4–6) showed any detectable binding toward MINP(7), unlike what was observed when the aliphatic guests (7–9) were tested with MINP(4) and MINP(6). The results suggest that our molecular imprinting was able to reproduce the shape of the linear hexanoyl group so well in the MINP(7) that the benzoyl groups could not fit into the binding pockets (Figure 2, bottom panel).

Our data so far indicate that the ion-pairing interaction on the surface of the micelle contributes little to the chiral recognition. To further confirm that hydrophobic interactions being dominant in our chiral recognition, we coupled a phenylalanine to 4 and 6—which could not be differentiated by MINP(4) effectively—to afford 10 and 11, respectively. If our hydrophobic hypothesis was correct, these compounds should be easily distinguished by their MINP receptor, since they have three hydrophobic groups with the added benzyl. Indeed, MINP(10) easily distinguished the two, showing a Krel of 0.017 for 11, despite that only one of three chiral centers was inverted in the compound. A pleasant outcome of the added hydrophobic group (i.e., benzyl) is the enhanced binding: Ka (= 420 × 104 M−1) for 10 by MINP(10) was the highest among all in Table 1. Thus, although nonspecific in nature, hydrophobic interactions can be extremely powerful in selective molecular recognition in water.

Conclusions

Separation of stereoisomers is one of the earliest applications of molecularly imprinted polymers.16, 17 A particular benefit of these materials in separation is the predictability of the selectivity, as the binding pocket is created from the original template. The predictble formation of binding pockets also makes it possible to use the imprinted polymers from one class of compounds for related compounds.74

In comparison to traditional MIPs, our imprinted micelles are characterized by their nanodimension, water-solubility, and a tunable number of binding sites. Chiral pockets can be generated inside these protein-sized receptors, as long as the template molecules possess hydrophobic groups that can be incorporated into the micelles. Using 4-proline derivatives as the model compounds, we were able to identify the key interactions responsible for the chiral recognition using this unique class of materials. Excellent enantio- and diastereoselectivity could be obtained in a straightforward manner.

One of the most interesting discoveries of this work is the predictable selectivity of the MINPs, not only toward close analogues but also toward more distant relatives., i.e., from aliphatic to aromatic derivatives and vice versa. Aliphatic and aromatic hydrophobes tend to behave differently in hydrophobic interactions.62 It is important both turned out reliable in our molecular imprinting performed in water. The interesting selectivities displayed by MINP(4) and MINP(7) for 4–6 vs 7–9 (Fig 2) confirmed the accuracy of the imprinting and gave us a way to tune the binding affinities while keeping the overall binding selectivity in the same order. This feature could be very useful in separation, as strong binding by the stationary phase frequently causes peak broadening during chromatography.

Experimental

Synthetic Procedures

Syntheses of compound 4–6 have been reported.75

Compound 7-COOH

The synthesis followed similar procedures used for 4–6.75 Triethylamine (TEA; 173.2 mg, 1.60 mmol) was added to a solution of (2R, 4R)-4-hydroxyproline (99.8 mg, 0.76 mmol) in a mixture of water/THF = 1/6 (12 mL) at 0 °C, followed by hexanoyl chloride (215.4 mg, 1.60 mmol). After 10 min, the water bath was removed and the mixture was heated to reflux for 4 h. After cooled to room temperature, the resulting solution was diluted with water (10 mL), acidified to pH = 2 using 1 M HCl, and extracted with methylene chloride (3 × 10 mL). The organic solution was washed with water (2 × 10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated in vacuo to give a white powder, which was purified by column chromatography over silica gel using 20:1 methylene chloride: methanol as the eluent to afford a white powder (188 mg, 76%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3/ DMSO-d6, δ): 5.32 (m, 1H), 4.62 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.47–2.16 (series of m, 4H), 1.67–1.53 (series of m, 4H), 1.27 (m, 8H), 0.85 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 173.3, 172.4, 172.3, 72.6, 57.4, 52.6, 42.7, 35.2, 35.2, 30.9, 30.9, 23.8, 23.8, 22.4, 22.4, 13.8, 13.8. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M-Na] − calcd for C17H28N2NO5, 326.1973; found, 326.1972.

Compound 8-COOH

The same procedure as above was followed, affording the product as a white powder (79%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3/ d-methanol, δ): 4.89 (m, 1H), 4.52 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.45–2.22 (series of m, 4H), 1.57–1.23 (series of m, 12H), 0.85 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 173.3, 172.4, 172.3, 72.6, 57.4, 52.6, 42.7, 35.2, 35.2, 30.9, 30.9, 23.8, 23.8, 22.4, 22.4, 13.8, 13.8. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M-Na]− calcd for C17H28N2NO5, 326.1973; found, 326.1968.

Compound 9-COOH

The same procedure as above was followed, affording the product as a white powder (81%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3/ DMSO-d6, δ): 5.32 (m, 1H), 4.62 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.47–2.16 (series of m, 4H), 1.67–1.53 (series of m, 4H), 1.27 (m, 8H), 0.86 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 173.3, 172.4, 172.3, 72.6, 57.4, 52.6, 42.7, 35.2, 35.2, 30.9, 30.9, 23.8, 23.8, 22.4, 22.4, 13.8, 13.8. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M-Na] − calcd for C17H28N2NO5, 326.1973; found, 326.1976.

Compound 10-COOH

A mixture of compound 7-COOH (62.2 mg, 0.19 mmol), N-hydroxysuccinimide (21.7 mg, 0.19 mmol), and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydro-chloride (EDCI, 36.4 mg, 0.19 mmol) in dry methylene chloride (5 mL) was stirred for 4 h. L-phenylalanine (36.3 mg, 0.22 mmol) in 0.6 M NaHCO3 (5 mL) was added. After being stirred at room temperature overnight, the reaction mixture was acidified by 1 M HCl to pH = 2 and extracted with methylene chloride (2 × 10 mL). The organic combined solution was washed with water (2 × 10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by preparative TLC using 12:1 methylene chloride/methanol as the developing solvent to afford the product as a yellowish gum (76 mg, 84 %). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 8.08 (m, 2H), 7.62 (m, 1H), 7.46 (m, 2H), 4.64 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.51 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (m, 1H), 3.61 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.40 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.43–2.21 (series of m 4H), 1.98–1.76 (s, 2H), 1.59–1.16 (series of m, 12 H), 0.88–0.79 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 179.5, 179.5, 179.5, 179.5, 133.2, 129.2, 128.4, 127.1, 69.9, 69.9, 59.7, 59.3, 55.3, 40.9, 39.5, 39.1, 33.8, 33.8, 32.0, 32.0, 24.4, 24.4, 22.3, 22.3, 13.7, 13.7. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M-Na] − calcd for C26H37N2O6, 473.2657; found, 496.2671.

Compound 11-COOH

The same procedure as above was followed, affording the product as a yellowish gum (85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD, δ): 8.07 (m, 2H), 7.61 (m, 1H), 7.47 (m, 2H), 4.66 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.53 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (m, 1H), 3.61 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H), 3.40 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.23 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 2.43–2.21 (series of m, 4H), 1.98–1.76 (s, 2H), 1.59–1.16 (series of m, 12 H), 0.88–0.79 (m, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 179.4, 179.4, 179.4, 179.4, 133.2, 129.1, 128.4, 127.1, 69.9, 69.9, 59.7, 59.3, 55.3, 40.9, 39.5, 39.1, 33.8, 33.8, 32.0, 32.0, 24.4, 24.4, 22.3, 22.3, 13.7, 13.7. ESI-HRMS (m/z): [M-Na] − calcd for C26H37N2O6, 473.2657; found, 496.2665.

Typical procedure for the synthesis of MINPs.30

To a micellar solution of compound 1 (9.3 mg, 0.02 mmol) in H2O (2.0 mL), divinylbenzene (DVB, 2.8 μL, 0.02 mmol), compound 4 in H2O (10 μL of a 14.1 mg/mL in H2O, 0.0004 mmol), and 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA,10 μL of a 12.8 mg/mL solution in DMSO, 0.0005 mmol) were added. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonication for 10 min before compound 2 (4.1 mg, 0.024 mmol), CuCl2 (10 μL of a 6.7 mg/mL solution in H2O, 0.0005 mmol), and sodium ascorbate (10 μL of a 99 mg/mL solution in H2O, 0.005 mmol) were added. After the reaction mixture was stirred slowly at room temperature for 12 h, compound 3 (10.6 mg, 0.04 mmol), CuCl2 (10 μL of a 6.7 mg/mL solution in H2O, 0.0005 mmol), and sodium ascorbate (10 μL of a 99 mg/mL solution in H2O, 0.005 mmol) were added. After being stirred for another 6 h at room temperature, the reaction mixture was transferred to a glass vial, purged with nitrogen for 15 min, sealed with a rubber stopper, and irradiated in a Rayonet reactor for 12 h. The reaction mixture was poured into acetone (8 mL). The precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with a mixture of acetone/water (5 mL/1 mL) three times, followed by methanol/acetic acid (5 mL/0.1 mL) three times. The product was dried in air to afford MINP(4). Yields generally were >80%.

ITC Titration

ITC was performed using a MicroCal VP-ITC Microcalorimeter with Origin 7 software and VPViewer2000 (GE Healthcare, Northampton, MA). The determination of binding constants by ITC followed standard procedures.76–78 In general, a solution of an appropriate guest in Millipore water was injected in equal steps into 1.43 mL of the corresponding MINP in the same solution. The top panel shows the raw calorimetric data. The area under each peak represents the amount of heat generated at each ejection and is plotted against the molar ratio of the MINP to the guest. The smooth solid line is the best fit of the experimental data to the sequential binding of N binding site on the MINP. The heat of dilution for the guest, obtained by titration carried out beyond the saturation point, was subtracted from the heat released during the binding. Binding parameters were auto-generated after curve fitting using Microcal Origin 7.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank NSF (DMR-1464927) and NIGMS (R01GM113883) for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Additional figures and NMR spectra of key compounds. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Pirkle WH, Pochapsky TC. Chem Rev. 1989;89:347–362. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthod A. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2093–2099. doi: 10.1021/ac0693823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hembury GA, Borovkov VV, Inoue Y. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1–73. doi: 10.1021/cr050005k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wulff G. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1995;34:1812–1832. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wulff G. Chem Rev. 2001;102:1–28. doi: 10.1021/cr980039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haupt K, Mosbach K. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2495–2504. doi: 10.1021/cr990099w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye L, Mosbach K. Chem Mater. 2008;20:859–868. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shea KJ. Trends Polym Sci. 1994;2:166–173. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sellergren B. Molecularly imprinted polymers: man-made mimics of antibodies and their applications in analytical chemistry. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komiyama M. Molecular imprinting: from fundamentals to applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmerman SC, Lemcoff NG. Chem Commun. 2004:5–14. doi: 10.1039/b304720b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yan M, Ramström O. Molecularly imprinted materials: science and technology. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander C, Andersson HS, Andersson LI, Ansell RJ, Kirsch N, Nicholls IA, O’Mahony J, Whitcombe MJ. J Mol Recognit. 2006;19:106–180. doi: 10.1002/jmr.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sellergren B, Hall AJ. In: Supramolecular Chemistry: From Molecules to Nanomaterials. Steed JW, Gale PA, editors. Wiley, Online; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haupt K, Ayela C. Molecular Imprinting. Springer; Heidelberg ; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wulff G, Sarhan A, Zabrocki K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1973;14:4329–4332. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wulff G, Vesper W. J Chromatogr. 1978;167:171–186. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sellergren B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2000;39:1031–1037. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000317)39:6<1031::aid-anie1031>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu X, Carroll WR, Shimizu KD. Chem Mater. 2008;20:4335–4346. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, Ding J, Day M, Tao Y. Macromolecules. 2006;39:2629–2636. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoshino Y, Kodama T, Okahata Y, Shea KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:15242–15243. doi: 10.1021/ja8062875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Priego-Capote F, Ye L, Shakil S, Shamsi SA, Nilsson S. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2881–2887. doi: 10.1021/ac070038v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cutivet A, Schembri C, Kovensky J, Haupt K. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14699–14702. doi: 10.1021/ja901600e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang KG, Berg MM, Zhao CS, Ye L. Macromolecules. 2009;42:8739–8746. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zeng ZY, Patel J, Lee SH, McCallum M, Tyagi A, Yan MD, Shea KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:2681–2690. doi: 10.1021/ja209959t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Y, Pan GQ, Zhang Y, Guo XZ, Zhang HQ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:1511–1514. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Çakir P, Cutivet A, Resmini M, Bui BT, Haupt K. Adv Mater. 2013;25:1048–1051. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Deng C, Liu S, Wu J, Chen Z, Li C, Lu W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:5157–5160. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen LX, Xu SF, Li JH. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:2922–2942. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00084a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Awino JK, Zhao Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:12552–12555. doi: 10.1021/ja406089c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Awino JK, Zhao Y. Chem Commun. 2014;50:5752–5755. doi: 10.1039/c4cc01516a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Awino JK, Zhao Y. Chem-Eur J. 2015;21:655–661. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awino JK, Hu L, Zhao Y. Org Lett. 2016;18:1650–1653. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Awino JK, Zhao Y. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2015;1:425–430. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.5b00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Awino JK, Gunasekara RW, Zhao Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:9759–9762. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gunasekara RW, Zhao Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:829–835. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Awino JK, Gunasekara RW, Zhao Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:2188–2191. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang S, Zhao Y. Macromolecules. 2010;43:4020–4022. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Zhao Y. Langmuir. 2012;28:4152–4159. doi: 10.1021/la2050702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y. Langmuir. 2016;32:5703–5713. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neuman RE, Logan MA. J Biol Chem. 1950;186:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berg RA, Prockop DJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;52:115–120. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)90961-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mizuno K, Hayashi T, Bächinger HP. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32373–32379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hong JI, Namgoong SK, Bernardi A, Still WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5111–5112. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breslow R, Yang Z, Ching R, Trojandt G, Odobel F. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3536–3537. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hossain MA, Schneider H-J. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:11208–11209. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamura H, Rekharsky MV, Ishihara Y, Kawai M, Inoue Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14224–14233. doi: 10.1021/ja046612r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tashiro S, Tominaga M, Kawano M, Therrien B, Ozeki T, Fujita M. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4546–4547. doi: 10.1021/ja044782y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright AT, Anslyn EV, McDevitt JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17405–17411. doi: 10.1021/ja055696g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmuck C, Wich P. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4277–4281. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reczek JJ, Kennedy AA, Halbert BT, Urbach AR. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2408–2415. doi: 10.1021/ja808936y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niebling S, Kuchelmeister HY, Schmuck C, Schlucker S. Chem Sci. 2012;3:3371–3377. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith LC, Leach DG, Blaylock BE, Ali OA, Urbach AR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:3663–3669. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Faggi E, Vicent C, Luis SV, Alfonso I. Org Biomol Chem. 2015;13:11721–11731. doi: 10.1039/c5ob01889g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sonzini S, Marcozzi A, Gubeli RJ, van der Walle CF, Ravn P, Herrmann A, Scherman OA. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:14000–14004. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peczuh MW, Hamilton AD. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2479–2494. doi: 10.1021/cr9900026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schmidtchen FP. In: Supramolecular Chemistry: From Molecules to Nanomaterials. Steed JW, Gale PA, editors. Wiley, Online; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Easson LH, Stedman E. Biochem J. 1933;27:1257–1266. doi: 10.1042/bj0271257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ogston AG. Nature. 1948;162:963. doi: 10.1038/162963b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dalgliesh CE. J Chem Soc. 1952:3940–3942. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abraham MH. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:2085–2094. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanford C. The Hydrophobic Effect: Formation of Micelles and Biological Membranes. 2. Krieger; Malabar, Fla: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ben-Naim A. Hydrophobic interactions. Plenum Press; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stillinger FH. Science. 1980;209:451–457. doi: 10.1126/science.209.4455.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dill KA. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7133–7155. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blokzijl W, Engberts JBFN. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:1545–1579. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Southall NT, Dill KA, Haymet ADJ. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:521–533. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chandler D. Nature. 2005;437:640–647. doi: 10.1038/nature04162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Berger M, Schmidtchen FP. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1998;37:2694–2696. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19981016)37:19<2694::AID-ANIE2694>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Linton BR, Goodman MS, Fan E, van Arman SA, Hamilton AD. J Org Chem. 2001;66:7313–7319. doi: 10.1021/jo010413y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rekharsky M, Inoue Y, Tobey S, Metzger A, Anslyn E. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:14959–14967. doi: 10.1021/ja020612e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tobey SL, Anslyn EV. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14807–14815. doi: 10.1021/ja030507k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Linton B, Hamilton AD. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:6027–6038. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hart BR, Rush DJ, Shea KJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:460–465. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Portoghese PS, Turcotte JG. Tetrahedron. 1971;27:961–967. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts JF, Lin LN. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jelesarov I, Bosshard HR. J Mol Recognit. 1999;12:3–18. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1352(199901/02)12:1<3::AID-JMR441>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Velazquez-Campoy A, Leavitt SA, Freire E. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;261:35–54. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-762-9:035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.