Abstract

Background

Ovarian carcinoma (OC) is the fifth most common female cancer and mostly diagnosed at an advanced stage. Surgical debulking is usually followed by adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. Only few biomarkers are known to be related to chemosensitivity. OX40 is a TNF receptor member and expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. It is known that OX40 signaling promotes survival and responds to various immune cells of the innate and adaptive immune system. Therefore we investigated the indicative value of OX40 expression for recurrence and survival in OC.

Methods

A tissue microarray of biopsies of mostly high-grade primary serous OC and matched recurrences of 47 patients was stained with OX40. Recurrence within 6 months of the completion of platinum-based chemotherapy was defined as chemoresistance.

Results

Chemosensitivity correlated significantly with high OX40 positive immune cell density in primary cancer biopsies (p = 0.027). Furthermore patients with a higher OX40 expression in recurrent cancer biopsies showed a better outcome in recurrence free survival (RFS) (p = 0.017) and high OX40 expression was associated with chemosensitivity (p = 0.008). OX40 positive TICI in recurrent carcinomas significantly correlated with IL-17 positive tumor infiltrating immune cells in primary carcinomas (rs = 0.34; p = 0.023). Univariate cox regression analysis revealed a significant longer RFS and higher numbers of chemotherapy cycles for high OX40 tumor cell expression in recurrent cancer biopsies (HR 0.39, 95%CI 0.16–0.94, p = 0.036 and 1.28, 95%CI 1.05–1.55; p = 0.013).

Conclusion

High OX40 expression in OC is correlated with chemosensitivity and improved RFS in OC. Patients might therefore benefit from a second line therapy.

Keywords: OX40, CD134, Ovarian cancer, Chemosensitivity

Background

Ovarian carcinoma (OC) is the fifth most common cause of all cancer related deaths in women and has an incidence of 5–15/100′000 in Europe [1–3]. Often it is diagnosed at a late disease stage [4] and treated with surgical debulking and adjuvant chemotherapy. Of the various subtypes of OC, high-grade serous carcinoma is the most common subtype [5]. After surgical debulking, adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy is currently the standard treatment modality.

It is known that tumor response to cytotoxic drugs shows great variability. The availability of predictive biomarkers for chemosensitivity of a given OC would be helpful to plan an individually adequate therapy. Such biomarkers would allow an individualized therapy with either repetitive chemotherapy cycles or extended surgical procedures or palliative care in cases of chemoresistance. Previous studies investigated several biomarkers related to chemosensitivity of platinum-based chemotherapy in OC, but only few helpful markers have so far been found [6–8].

It is widely known that tumor microenvironment influences tumor biology and that tumor behavior is affected by the immunological environment. Based on this background, a variety of different cancers with strong lymphatic infiltration have been investigated [9]. Especially in OC it has been shown that an increased number of intratumoral T cells correlates with an improved clinical outcome [9, 10]. Furthermore, in metastatic colorectal cancer the response to chemotherapy is associated with a high T cell density [11].

OX40 (CD134) is a co-stimulatory trans-membrane molecule and belongs to the tumor necrosis factor-receptor superfamily [12–14]. It is expressed on activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as on other cell types [15–18]. The OX40 ligand, expressed by antigen-presenting cells (APC), activates the OX40 signaling pathway which promotes a robust immune response. The interaction of OX40 with OX40 ligand results in enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ cell proliferation, stimulated cytokine production, and increased survival of antigen-specific memory T cell [19–21]. In mice the absence of OX40 has been shown to cause a strong reduction in the number of effector memory CD4+ cells [22]. Furthermore, the CD8+ response was reduced and tumor growth was accelerated [19]. Accordingly, it is comprehensible that the immune-stimulating properties of OX40 agonists could overcome some of the immunosuppressive properties within tumor environment [23].

In a first clinical trial, OX40 targeted immunotherapy treatment has been tested in patients with different types of cancer and patients showed tumor regression after only one cycle of treatment. Furthermore, a significant dose-dependent increase in proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was observed [24].

In a previous study by our group, we could demonstrate that infiltration with IL-17-positive tumor immune cell is indicative for an enhanced response to chemotherapy in primary and recurrent OC [25]. IL-17 has been shown to be produced by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes as well as by granulocytes and other innate immune cells [26–28]. Additionally, in another study we were able to show that high density of myeloperoxidase (MPO) positive cell enhances the indicative value of IL-17 for response to chemotherapy in ovarian carcinoma [29].

In the future, adjuvant chemotherapy of patients with OC should be improved by an adapted regimen according to predictive markers on chemoresistance and –sensitivity. In the present study we investigated whether the analysis of OX40 could add significant value to available biomarkers and help predict chemosensitivity. The aim of this study was to address the predictive value of OX40 in OC. Our approach was based on the assumption that antitumor activity of chemotherapy regimen is partially based on the interaction between tumor cells and the immune system in a complex process [30].

Methods

Patients

One or two (in one third of the patients) tissueblocks from the resected high-grade serous OC and their recurrences from 47 patients were collected from the Institutes of Pathology of the University Hospital of Basel and the Cantonal Hospitals of Baden, Liestal, and St. Gallen, Switzerland (5.7% FIGO stage II, 84.3% FIGO stage III, and 4.3% FIGO stage IV) [31, 32]. All patients had initial surgical debulking, followed by at least three cycles of platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy. All patients developed recurrences after initial surgery. In terms of response to chemotherapy, women were divided into a chemosensitive and a chemoresistant group according to the date of recurrence. Recurrence that occurred within 6 months after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy was defined as chemoresistant disease while recurrence diagnosed at a later state was defined as chemosensitive [33].

The statement concerning the clinical data collection and ethical considerations can be found in our previous publications [25, 34–37].

Tissue microarray

The construction of the tissue microarray has been previously described. Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks of the resected tumor were prepared to construct the TMA. A representative tissue region of the hematoxylin-eosin stained tumor was selected and tissue cylinders of 0.6 mm in diameter were punched and sections of 3 μm transferred to the glass slide were they were available for immunohistochemial stainings [25, 38].

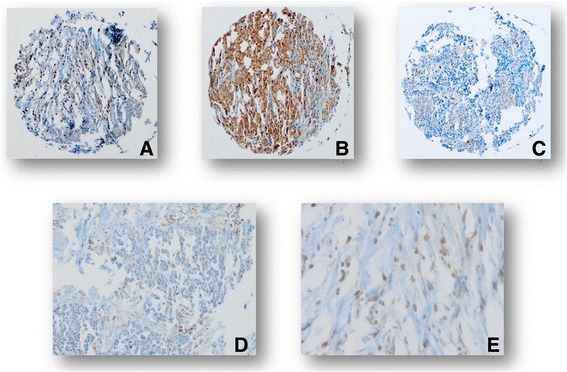

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and visual analysis

Standard indirect immunoperoxidase procedures (ABC-Elite, Vectra Laboratories) were used for immunohistochemistry. The TMA was stained for OX40 (clone Abcam ab119904) and each tissue spot was assessed twice. First, in each biopsy all positively stained tumor infiltrating immune cells (TICI) were counted. Second, in each biopsy only OX40-positive tumor cells were counted. Fibroblasts and macrophages were not counted. The assessment included the whole section plane of all biopsies. Intravascular located immune cells were excluded from analysis (Fig. 1). Two examiners (MR and SE) analysed the staining independently. The number of OX40 positive immune cells per punch were allocated to a high or low expression group (cut-off in primary carcinoma = 36.5 and cut-off in recurrent carcinoma = 2.5). For OX40 tumor cell expression the corresponding cut-off values were 144.5 for primary and 12.5 for recurrent carcinoma. Biopsies with less than 25% of morphologically preserved tissue were excluded from analysis. Conclusive data for OX40 was available in 47 biopsies of primary and 44 biopsies of matched recurrent carcinomas.

Fig. 1.

Example of high OX40 immune cell density (a), high OX40 tumor expression (b) and low immune cell density and low OX40 tumor expression (c) (10×). Positive immune cells (D (20×), E (40×)).

Statistical analysis section

The assumption of proportional hazards was verified for the marker by analyzing the correlation of Schoenfeld residuals and the ranks of individual failure times. Any missing clinicopathological information was assumed to be missing at random. Subsequently, a multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed. The hazard ratios (HR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to determine prognostic effects on survival time. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to analyze the correlation between OX40 tumor expression, OX40 immune cell density and IL-17. All statistical analyses were made using STATA software version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Cut-off scores to classify OC with low or high OX40 infiltration/expression were obtained by regression tree analysis, evaluating the best threshold in order to predict patients’ survival status, on all tumor samples [39]. IL-17 data were available from our previous publication [25, 29]. Kruskal Wallis, Chi-Square or Fisher’s Exact tests were used for the association of the clinicopathological features with the corresponding four groups of the biomarkers. Univariate recurrence-free and overall survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method and log rank test.

Results

Patient characteristics

Median age of the cohort was 58.5 years (range 34–77). Thirty-eight patients (80.9%) had FIGO-stage III cancer. 70.2% (n = 33) were chemosensitive and 29.8% (n = 14) chemoresistant. The overall 6-month recurrence free survival (RFS) rate was 0.53 (0.38–0.66) and the corresponding 3-year overall survival (OS) rate was 0.47 (0.29–0.63) (Table 1). Expectedly, RFS and OS were significantly shorter for the patients in the chemoresistant group compared to the patients in the chemosensitive group (RFS: 2.2 ± 0.3 vs 18.2 ± 2.0 months, p < 0.0001 and OS: 27 ± 5.3 vs. 49.6 ± 4.0 months, p = 0.0003, respectively).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 47)a

| N = 47 (100%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 58 (34–77) |

| FIGO stage | |

| II | 1 (2.1) |

| IIIA | 1 (2.1) |

| IIIB | 5 (10.6) |

| IIIC | 32 (68.2) |

| IV | 8 (17.0) |

| Residual disease | |

| None | 16 (34.0) |

| < 2 cm | 17 (36.2) |

| > 2 cm | 13 (27.7) |

| Numbers of chemotherapy cycles | |

| < 6 | 7 (14.9) |

| 6 or more | 39 (83.0) |

| CSb | 33 (70.2) |

| CRb | 14 (29.8) |

| 6-month RFS % (95%CI)c | 0.53 (0.38–0.66) |

| 3-year OS % (95%CI)c | 0.47 (0.29–0.63) |

amissing clinicopathological information was assumed to be missing at random

bCS chemosensitive, CR chemoresistant

cRFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

OX40 positive immune cell infiltration in primary and recurrent OC

The mean number of infiltrating OX40 positive immune cell in primary and recurrent cancer biopsies was 25.6 (±4.5 SE) and 25.6 (±8.5 SE), respectively.

We found a significant association between high numbers of OX40 positive tumor infiltrating immune cells and improved chemosensitivity in primary cancer biopsies (p = 0.027) (Table 2). On the other hand, no significant association of immune cell count and chemosensitivity or resistance was found in biopsies from recurrent carcinomas (Table 3).

Table 2.

Patients’ characteristics according to dichotomized distribution of OX40 positive immune cells in primary cancer biopsies in the overall cohort (cut-off = 36.5 cells; n = 47)a

| OX40 high | OX40 low | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 14 (100%) | n = 33 (100%) | ||

| Age (median, range) | 57 (41–73) | 59 (34–77) | 0.464 |

| FIGO stage | 0.795 | ||

| II | 0 | 1 (3.0) | |

| IIIA | 0 | 1 (3.0) | |

| IIIB | 2 (14.3) | 3 (9.1) | |

| IIIC | 11 (78.6) | 21 (63.6) | |

| IV | 1 (14.1) | 7 (21.2) | |

| Residual disease | 0.243 | ||

| None | 7 (50.0) | 9 (27.3) | |

| < 2 cm | 5 (35.7) | 12 (36.4) | |

| > 2 cm | 2 (14.3) | 11 (33.3) | |

| Numbers of chemotherapy cycles | 0.057 | ||

| < 6 | 0 | 7 (21.2) | |

| 6 or more | 14 (100.0) | 25 (75.8) | |

| CSb | 13 (93.0) | 20 (60.6) | 0.027 |

| CRb | 1 (14.1) | 13 (39.4) | |

| 6-month RFS % (95%CI)c | 0.71 (0.41–0.88) | 0.45 (0.28–0.61) | 0.461 |

| 3-year OS % (95%CI)c | 0.38 (0.10–0.67) | 0.46 (0.26–0.64) | 0.780 |

apercentages may not add to 100% due to missing values of defined variables, missing clinicopathological information was assumed to be missing at random. Variables are indicated as absolute numbers, %, median or range. Age, RFS and OS were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. FIGO stage, residual disease, numbers of chemotherapy cycles and chemoresistance were analyzed using the Chi-Square or the Fisher’s Exact test

bCS chemosensitive, CR chemoresistant

cRFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

Table 3.

Patients’ characteristics according to dichotomized distribution of OX40 positive immune cells in recurrent cancer biopsies in the overall cohort (cut-off = 2.5 cells; n = 44)a

| OX40 high | OX40 low | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 28 (100%) | n = 16 (100%) | ||

| Age (median, range) | 56.5 (34–73) | 63.5 (41–77) | 0.329 |

| FIGO stage | |||

| II | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 0.821 |

| IIIA | 0 | 1 (6.3) | |

| IIIB | 3 (10.7) | 2 (12.5) | |

| IIIC | 19 (67.9) | 10 (62.5) | |

| IV | 5 (17.9) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Residual disease | |||

| None | 10 (35.7) | 5 (31.3) | 0.850 |

| < 2 cm | 11 (39.3) | 5 (31.3) | |

| > 2 cm | 7 (25.0) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Numbers of chemotherapy cycles | |||

| < 6 | 5 (17.9) | 2 (12.5) | 0.702 |

| 6 or more | 23 (82.1) | 13 (81.3) | |

| CSb | 22 (78.6) | 9 (56.3) | 0.118 |

| CRb | 6 (21.4) | 7 (43.8) | |

| 6-month RFS % (95%CI)c | 0.57 (0.37–0.73) | 0.44 (0.20–0.66) | 0.622 |

| 3-year OS % (95%CI)c | 0.41 (0.19–0.63) | 0.54 (0.25–0.76) | 0.774 |

apercentages may not add to 100% due to missing values of defined variables, missing clinicopathological information was assumed to be missing at random. Variables are indicated as absolute numbers, %, median or range. Age, RFS and OS were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. FIGO stage, residual disease, numbers of chemotherapy cycles and chemoresistance were analyzed using the Chi-Square or the Fisher’s Exact test

bCS chemosensitive, CR chemoresistant

cRFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

Regarding the OX40 immune cell density (high vs. low), neither in primary nor recurrent cancer a significant association with clinicopathological features like FIGO stage, residual disease, numbers of chemotherapy cycles was shown. Also no correlation with RFS or OS was found (Tables 2 and 3).

OX40 positive tumor expression in primary and recurrent OC

The mean number of positive OX40 tumor expression in primary and recurrent cancer biopsies was 214.0 (±28.6 SE) and 231.4 (±57.9 SE), respectively.

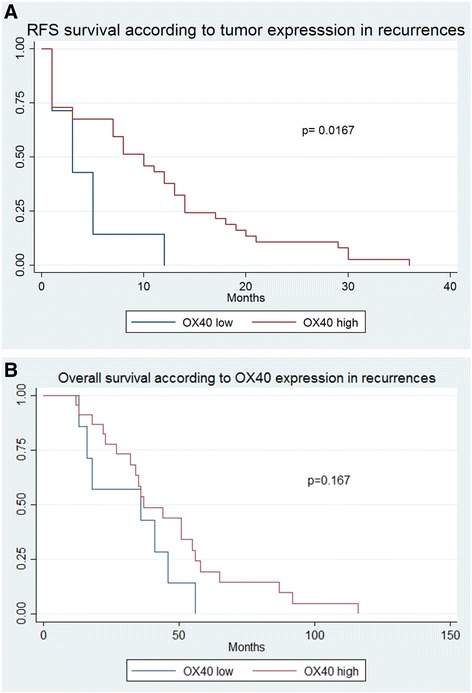

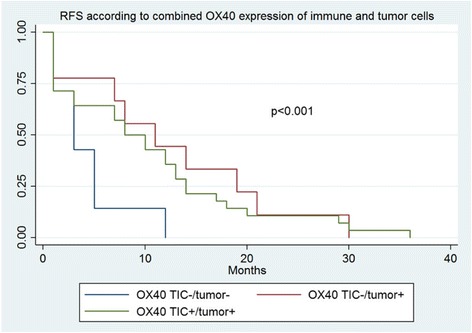

Patients with high OX40 expression in tumor cells in recurrent cancer biopsies showed a significantly increased chemosensitivity (p = 0.008) and improved 6-month RFS compared to patients with a low count of OX40 positive tumor cells (p = 0.017) (Table 4 and Fig. 2a). In contrast, OS did not significantly differ between the two groups (Fig. 2b). Additionally, no significant association was observed regarding response to chemotherapy in primary OC (Table 5). When combining OX40 positive and negativ immune and tumor cells, a significant worse RFS for the group with negative immune cells as well as negative tumor cells was found (Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Patients’ characteristics according to dichotomized distribution of OX40 expression by tumor cells in recurrent cancer biopsies in the overall cohort (cut-off = 12.5; n = 44)a

| OX40 high | OX40 low | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 37 (100%) | n = 7 (100%) | ||

| Age (median, range) | 57 (34–77) | 63 (41–76) | 0.386 |

| FIGO stage | |||

| II | 1 (2.7) | 0 | 0.777 |

| IIIA | 1 (2.7) | 0 | |

| IIIB | 5 (13.5) | 0 | |

| IIIC | 24 (64.9) | 5 (71.4) | |

| IV | 6 (16.2) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Residual disease | |||

| None | 13 (35.1) | 2 (28.6) | 0.406 |

| < 2 cm | 15 (40.5) | 1 (14.3) | |

| > 2 cm | 9 (24.3) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Numbers of chemotherapy cycles | |||

| < 6 | 7 (18.9) | 0 | 0.244 |

| 6 or more | 30 (81.0) | 6 (85.7) | |

| CSb | 29 (78.4) | 2 (28.6) | 0.008 |

| CRb | 8 (21.6) | 5 (71.4) | |

| 6-month RFS % (95%CI)c | 0.59 (0.42–0.73) | 0.14 (0.01–0.46) | 0.017 |

| 3-year OS % (95%CI)c | 0.48 (0.27–0.66) | 0.43 (0.10–0.73) | 0.167 |

apercentages may not add to 100% due to missing values of defined variables, missing clinicopathological information was assumed to be missing at random. Variables are indicated as absolute numbers, %, median or range. Age, RFS and OS were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. FIGO stage, residual disease, numbers of chemotherapy cycles and chemoresistance were analyzed using the Chi-Square or the Fisher’s Exact test

bCS chemosensitive, CR chemoresistant

cRFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

Fig. 2.

a Kaplan Meier survival curve of recurrence-free survival according to OX40 expression in recurrent cancer biopsies, Impact of OX40+ expression by tumor cells in recurrent cancer biopsies on recurrence-free survival in patients with high grade ovarian carcinoma. Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free survival curve was split according to OX40+ expression in patients bearing high grade ovarian carcinoma as indicated. Cut-off value established by regression tree analysis was 12.5 cells/punch. Blue line indicates to tumors with low OX40+ expression and red line refers to tumors with high OX40+ expression. b Impact of OX40+ expression by tumor cells in recurrent cancer biopsies on overall survival in patients with high grade ovarian carcinoma. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curve was split according to OX40+ expression in patients bearing high grade ovarian carcinoma as indicated. Cut-off value established by regression tree analysis was 12.5 cells/punch. Blue line indicates to tumors with low OX40+ expression and red line refers to tumors with high OX40+ expression.

Table 5.

Patients’ characteristics according to dichotomized distribution of OX40 expression by tumor cells in primary cancer biopsies in the overall cohort (cut-off = 144.5; n = 47)a

| OX40 high | OX40 low | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 27 (100%) | n = 20 (100%) | ||

| Age (median, range) | 58 (34–73) | 64 (39–77) | 0.197 |

| FIGO stage | |||

| II | 1 (3.7) | 0 | 0.643 |

| IIIA | 0 | 1 (5.0) | |

| IIIB | 4 (14.8) | 1 (5.0) | |

| IIIC | 18 (66.7) | 14 (70.0) | |

| IV | 4 (14.8) | 4 (20.0) | |

| Residual disease | |||

| None | 11 (40.7) | 5 (25.0) | 0.277 |

| < 2 cm | 10 (37.0) | 7 (35.0) | |

| > 2 cm | 5 (18.5) | 8 (40.0) | |

| Numbers of chemotherapy cycles | |||

| < 6 | 3 (11.1) | 4 (20.0) | 0.428 |

| 6 or more | 23 (85.2) | 16 (80.0) | |

| CSb | 20 (74.1) | 13 (65.0) | 0.501 |

| CRb | 7 (25.9) | 7 (35.0) | |

| 6-month RFS % (95%CI)c | 0.56 (0.35–0.72) | 0.50 (0.27–0.69) | 0.472 |

| 3-year OS % (95%CI)c | 0.43 (0.22–0.62) | 0.45 (0.17–0.71) | 0.869 |

apercentages may not add to 100% due to missing values of defined variables, missing clinicopathological information was assumed to be missing at random. Variables are indicated as absolute numbers, %, median or range. Age, RFS and OS were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. FIGO stage, residual disease, numbers of chemotherapy cycles and chemoresistance were analyzed using the Chi-Square or the Fisher’s Exact test

bCS chemosensitive, CR chemoresistant

cRFS recurrence-free survival, OS overall survival

Fig. 3.

Kaplan Meier survival curve of recurrence-free survival according to OX40 expression of immune and tumor cells.

OX40 positive immune cell infiltration and tumor expression by chemosensitivity

The number of OX40 positive tumor cells in the chemosensitive and chemoresistant group were 225.2 (±36.7 SE) vs 187.8 (±43.1 SE) (p = 0.585) in primary cancer biopsies and 266.8 (±76.5 SE) vs 147.0 (±49.5 SE) (p = 0.126) in recurrent cancer biopsies. The corresponding values for OX40 positive immune cells were 30.0 (±6.0 SE) vs 15.3 (±3.7 SE) (p = 0.149) and 31.7 (±11.5 SE) vs 11.2 (±3.8 SE) (p = 0.126), respectively.

Correlation analysis of OX40 positive immune cell infiltration and tumor expression

Further we performed a correlation analysis. There was significant correlation between OX40 positive tumor cells and TICI in primary OC (rho = 0.662; p < 0.001) as well as in recurrent OC (rho = 0.658; p < 0.001). No correlation was found for OX40 positive tumor cells in primary or recurrent OC (rho = 0.277; p = 0.069). On the other hand, the correlation between TICI in primary and recurrent OC was statistically significant (rho = 0.543; p < 0.001). However, there was no synergistic effect combining the two scores as RFS was not influenced (data not shown).

Uni- and multivariate cox regression survival analysis

In univariate cox regression survival analysis, high density of OX40 positive tumor cells in recurrent cancer biopsies was significantly associated with longer RFS (HR 0.39, 95%CI 0.16–0.94, p = 0.036) (Table 6). Additionally, residual disease of more than 2 cm and the number of chemotherapy cycles received also showed a significant correlation with RFS (HR 3.67, 95%CI 1.62–8.31 (p = 0.002) and HR 1.28, 95%CI 1.05–1.55; (p = 0.013), respectively). Lastly, in multivariate analysis no significant correlation to RFS was found regarding patient’s age, residual disease, FIGO classification and number of chemotherapy cycles (Table 6).

Table 6.

Uni- and multivariate Hazard Cox regression analysis of recurrence-free survival considering the dichotomized tumor expression in recurrent cancer biopsies

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-values | HR | 95% CI | p-values | |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.97 - 1.03 | 0.888 | 1.00 | 0.97 - 1.03 | 0.819 |

| OX40high vs OX40low | 0.39 | 0.16 - 0.94 | 0.036 | 0.74 | 0.18 - 3.01 | 0.676 |

| Residual disease < 2 cm | 1.13 | 0.56 - 2.28 | 0.724 | 0.88 | 0.40 - 1.91 | 0.747 |

| Residual disease > 2 cm | 3.67 | 1.62 - 8.31 | 0.002 | 2.78 | 1.09 - 7.06 | 0.032 |

| No. of chemotherapy cycles | 1.28 | 1.05 - 1.55 | 0.013 | 1.12 | 0.82 - 1.53 | 0.477 |

| FIGO IIIA | 0.34 | 0.02 - 5.72 | 0.455 | 0.43 | 0.02 - 8.31 | 0.573 |

| FIGO IIIB | 0.93 | 0.11 - 8.04 | 0.944 | 0.90 | 0.10 - 8.17 | 0.928 |

| FIGO IIIC | 1.21 | 0.16 - 9.03 | 0.851 | 1.02 | 0.13 - 8.24 | 0.985 |

| FIGO IV | 1.48 | 0.18 - 11.94 | 0.712 | 0.99 | 0.11 - 9.00 | 0.991 |

Multivariate analyses showing Hazard Ratios and p-value for all recurrent cancer biopsies (n = 43 less than 44 due to missing value) conferred by categorized OX40 expression, age, residual disease after cytoreductive surgery, number of chemotherapy cycles and FIGO classification

Correlation analysis of OX40 and IL-17 positive tumor immune cell infiltration

In order to investigate a possible association between OX40 and IL-17 positive tumor immune cell infiltration, a correlation analysis was performed. OX40 positive immune cells in recurrent carcinomas correlated significantly with IL-17 positive immune cells in primary carcinomas (rs = 0.34; p = 0.023). No other significant correlation was found between OX40 and IL-17 expression (Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlation analysis of OX40 and IL-17 positive tumor immune cell infiltration

| IL-17+ TICI in primarya | IL-17 + TICI in recurrentb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OX40+ TICI in primaryc | rs | 0.176 | 0.002 |

| p | 0.254 | 0.989 | |

| OX40+ TICI in recurrentd | rs | 0.341 | 0.245 |

| p | 0.023 | 0.109 | |

| OX40+ tumor in primarye | rs | 0.096 | 0.049 |

| p | 0.537 | 0.755 | |

| OX40+ tumor in recurrentf | rs | 0.276 | 0.205 |

| p | 0.070 | 0.182 | |

Correlation analysis of OX40 and IL-17 showing rho and p-value

aIL-17 positive immune cells in primary cancer biopsies

bIL-17 positive immune cells in recurrent cancer biopsies

cOX40 positive immune cells in primary cancer biopsies

dOX40 positive immune cells in recurrent cancer biopsies

eOX40 expression by tumor cells in primary cancer biopsies

f OX40 expression by tumor cells in recurrent cancer biopsies

Discussion

Surgical debulking followed by platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard treatment for OC. High-grade serous carcinomas are characterized by initial good response to chemotherapy with subsequent acquisition of increasing resistance at each recurrence [4, 40, 41]. Current second-line therapies are generally not curative, resulting in short term progression-free survival for most patients [41].

As stated, it would be helpful to have predictive biomarkers for chemoresistance and -sensitivity for an individualized therapy regimen. Additional survival benefit could be achieved by extended chemotherapy or repetitive surgical procedures depending on the assumed response to chemotherapy. We therefore examined the indicative value of OX40 for chemosensitivity in OC.

As previously mentioned the occurrence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes delay tumor progression through several mechanisms and is associated with survival benefits in a variety of patients with different tumors [10, 42]. Furthermore, in advanced ovarian cancer intratumoral T cells has been shown to correlate with improved clinical outcome [9, 10]. We could show that primary tumors with a high incidence of OX40 immune cell infiltration were significantly more often chemosensitive. Accordingly, they showed a delayed tumor recurrence, at earliest 6 months after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy.

Most importantly, our study shows that patients with a higher incidence of OX40 receptors expressed by the tumor cells have an improved RFS and show increased chemosensitivity in their recurrent cancer.

In line with this study, experimental models show that OX40 co-stimulatory molecule enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ cell proliferation, stimulated cytokine production, and increased survival of antigen-specific memory T cell [19–21].

OX40 targeted immunotherapy treatment has already been tested in a clinical trial for a variety of cancers. They could show tumor regression after just one cycle of mouse monoclonal antibody that agonizes human OX40 signaling in patients with advanced cancer [24].

The results of our study underline the importance of OX40 expression in recurrent OC tissue for prolonged recurrent free survival.

In our previous study, we identified IL-17 positive TICI as a predictive marker for chemosensitivity in primary and recurrent OC [25]. Interestingly, in the current study, OX40 positive TICI in recurrent carcinomas significantly correlated with IL-17 positive TICI in primary carcinomas. Additional larger studies are necessary to achieve an in-depth understanding of the interaction between OX40 and IL-17 and response to chemotherapy in OC.

Conclusion

Based on our results, OX40 receptor expression seems to be a valid marker for a personalized treatment concerning a second line therapy for patients with ovarian cancer. We suggest that patients with a high OX40 tumor cell expression in recurrent carcinoma might benefit from repeated chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The TMA construction was supported by the Swiss Cancer League (Oncosuisse) grant to GS (No. OCS 01506–02-2004). The funding body did not have any influence on the design of the study, data collection, analysis or interpretation or writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Raw data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen-presenting cells

- CI

Confidence intervals

- HR

Hazard ratios

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- OC

Ovarian carcinoma

- OS

Overall survival

- RFS

Recurrent free survival

- TICI

Tumor immune cell infiltration

- TMA

Tissue microarrays

Authors’ contributions

RD did the study design and drafted the manuscript. MR and SE performed the IHC evaluation and did the literature search. RD did the statistical analysis and was involved in revising the manuscript. UG, SS and LT collected data and were involved in revising the manuscript. LT, SD, BW, MK, RM, AT and TD contributed to the manuscript content and its revision. GS collected samples and data, contributed to the IHC evaluation and revised the manuscript. All authors read and gave approval to the final manuscript version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the regional ethics committee of the University Hospital Basel Switzerland. Finally, the study was performed according to the guidelines of the institutional review boards (IRB) of the participating institutions as previously published [34–37]. The need for patient consent for studies using this TMA was originally waived by the ethics committee of northwestern Switzerland (EKNZ). Currently the TMA is handed at the biobank of th Institute of Pathology of the University Hospital Basel.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Michaela Ramser, Email: michaela.Ramser@usb.ch.

Simone Eichelberger, Email: simone.eichelberger@stud.unibas.ch.

Silvio Däster, Email: silvio.daester@usb.ch.

Benjamin Weixler, Email: benjamin.weixler@charite.de.

Marko Kraljević, Email: marko.kraljevic@gmail.com.

Robert Mechera, Email: robert.mechera@usb.ch.

Athanasios Tampakis, Email: athanasios.tampakis@usb.ch.

Tarik Delko, Email: tarik.delko@usb.ch.

Uwe Güth, Email: uwe.gueth@unibas.ch.

Sylvia Stadlmann, Email: sylvia.stadlmann@ksb.ch.

Luigi Terracciano, Email: luigi.terracciano@usb.ch.

Raoul A. Droeser, Email: raoul.droeser@usb.ch

Gad Singer, Email: gad.singer@ksb.ch.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, et al. Ovarian cancer in Europe: cross-sectional trends in incidence and mortality in 28 countries, 1953-2000. Int J Cancer. 2005;113(6):977–990. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fraser M, et al. Chemoresistance in human ovarian cancer: the role of apoptotic regulators. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2003;1(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-1-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coburn SB, et al. International patterns and trends in ovarian cancer incidence, overall and by histologic subtype. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(11):2451–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.He Z, et al. S100P contributes to chemosensitivity of human ovarian cancer cell line OVCAR3. Oncol Rep. 2008;20(2):325–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato S, et al. Chemosensitivity and p53-dependent apoptosis in epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86(7):1307–1313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1307::AID-CNCR28>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polcher M, et al. Foxp3(+) cell infiltration and granzyme B (+)/Foxp3 (+) cell ratio are associated with outcome in neoadjuvant chemotherapy-treated ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59(6):909–919. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0817-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fridman WH, et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):298–306. doi: 10.1038/nrc3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, et al. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(3):203–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halama N, et al. Localization and density of immune cells in the invasive margin of human colorectal cancer liver metastases are prognostic for response to chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2011;71(17):5670–5677. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gough MJ, Weinberg AD. OX40 (CD134) and OX40L. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;647:94–107. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-89520-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croft M, et al. The significance of OX40 and OX40L to T-cell biology and immune disease. Immunol Rev. 2009;229(1):173–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Croft M. The role of TNF superfamily members in T-cell function and diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(4):271–285. doi: 10.1038/nri2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redmond WL, Ruby CE, Weinberg AD. The role of OX40-mediated co-stimulation in T cell activation and survival. Crit Rev Immunol. 2009;29(3):187–201. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v29.i3.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croft M. Control of immunity by the TNFR-related molecule OX40 (CD134) Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:57–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugamura K, Ishii N, Weinberg AD. Therapeutic targeting of the effector T-cell co-stimulatory molecule OX40. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(6):420–431. doi: 10.1038/nri1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinberg AD, et al. The generation of T cell memory: a review describing the molecular and cellular events following OX40 (CD134) engagement. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(6):962–972. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bansal-Pakala P, et al. Costimulation of CD8 T cell responses by OX40. J Immunol. 2004;172(8):4821–4825. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Smedt T, et al. Ox40 costimulation enhances the development of T cell responses induced by dendritic cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2002;168(2):661–670. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maxwell JR, et al. Danger and OX40 receptor signaling synergize to enhance memory T cell survival by inhibiting peripheral deletion. J Immunol. 2000;164(1):107–112. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soroosh P, et al. Differential requirements for OX40 signals on generation of effector and central memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5014–5023. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gough MJ, et al. OX40 agonist therapy enhances CD8 infiltration and decreases immune suppression in the tumor. Cancer Res. 2008;68(13):5206–5215. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curti BD, et al. OX40 is a potent immune-stimulating target in late-stage cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2013;73(24):7189–7198. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Droeser RA, et al. High IL-17-positive tumor immune cell infiltration is indicative for chemosensitivity of ovarian carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139(8):1295–1302. doi: 10.1007/s00432-013-1441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, et al. IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-gamma-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):331–342. doi: 10.1172/JCI38702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin AM, et al. Mast cells and neutrophils release IL-17 through extracellular trap formation in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2011;187(1):490–500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cua DJ, Tato CM. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(7):479–489. doi: 10.1038/nri2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Droeser RA, et al. MPO density in primary cancer biopsies of ovarian carcinoma enhances the indicative value of IL-17 for chemosensitivity. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:639. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2673-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng J, et al. Chemotherapy induces programmed cell death-ligand 1 overexpression via the nuclear factor-kappaB to Foster an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75(23):5034–5045. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer G, et al. Diverse tumorigenic pathways in ovarian serous carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(4):1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62549-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singer G, et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS characterize the development of low-grade ovarian serous carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(6):484–486. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jazaeri AA, et al. Gene expression profiles associated with response to chemotherapy in epithelial ovarian cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(17):6300–6310. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stadlmann S, et al. ERCC1-immunoexpression does not predict platinum-resistance in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(1):252–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stadlmann S, et al. Glypican-3 expression in primary and recurrent ovarian carcinomas. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2007;26(3):341–344. doi: 10.1097/pgp.0b013e31802d692c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stadlmann S, et al. Expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma and cyclo-oxygenase 2 in primary and recurrent ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(3):307–310. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.035717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stadlmann S, et al. Epithelial growth factor receptor status in primary and recurrent ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(4):607–610. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sauter G, Simon R, Hillan K. Tissue microarrays in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2(12):962–972. doi: 10.1038/nrd1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zlobec I, et al. Selecting immunohistochemical cut-off scores for novel biomarkers of progression and survival in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(10):1112–1116. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.044537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ledermann JA, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl_6):vi24–vi32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jayson GC, et al. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1376–1388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leffers N, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-infiltrating T-lymphocytes in primary and metastatic lesions of advanced stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;58(3):449. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0583-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.