Abstract

Background:

Acne vulgaris is a common skin condition which affects most adolescents. It has a major impact on quality of life and psychosocial well-being.

Aims:

The aims of the study were to examine the psychosocial effects of acne on adolescents and changes in quality of life, and to reveal any difference in the possible effect between genders. In addition, an investigation of the association between acne severity and quality of life as well as psychosocial stress was conducted.

Materials and Methods:

The present study included 164 adolescents with a mean age of 12–18 years and was diagnosed with acne vulgaris without any previous treatment. The control group consisted of 188 healthy volunteers. Acne severity was evaluated by the global acne grading system. All patients filled in a Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index, Pediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire (PedsQL), and a Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

Results:

The scores of SDQ and PedsQL were significantly lower in the case group. There was no significant correlation found between the genders in the control group for acne severity and scale scores. No significant correlation was found between acne severity and psychosocial challenges.

Conclusions:

The results of the present study show that acne has a significant effect on quality of life for adolescents, and this has an impact on their psychosocial life. Another important finding of the present study is that worsening in quality of life is not affected by some factors such as duration, severity of acne and age.

Keywords: Acne, adolescent, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index, psychosocial impact, quality of life

What was known?

Acne vulgaris mostly affects adolescents and has a major impact on quality of life and psychosocial well-being.

Acne vulgaris has been related to psychiatric morbidity.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease of pilosebaceous unit presenting with seborrhea, open and closed comedone, papule, pustule, and nodulocystic lesion in severe cases.[1] It may be detected in more than 85% of adolescents, and approximately 50% of the cases face this problem until adulthood.[2] Acne is also associated with a great psychological load.[3] Acne frequently affects face, the presenting part of the body and may cause shame, a sense of guilt and social isolation. It is usually observed during adolescence, which is an important period for the development of self-identity and external appearance, with prominent social and physical changes in children's lives. Adolescents with acne lesions may experience behavioral and emotional problems during this sensitive period. It has been reported that individuals with acne experience dissatisfaction and shame due to their appearance and a decrease in self-confidence.[4,5] Furthermore, an increase in the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic findings such as low self-respect, difficult social relations, social phobia, pain, and indisposition are often seen in patients with acne.[6,7] In addition, these patients are more susceptible to withdrawal, depression, anxiety, and anger.[8] Since acne may affect quality of life as much as other systemic diseases[9] and cause significant psychosocial difficulties in adolescents and especially in sensitive individuals, such negative effects are not surprising.

Adolescence is an important period both for identity and social development; therefore, the problems that adolescents may face due to their physical appearance may cause some psychological problems that may affect them into adulthood. Therefore, the aims of the present study were to examine the psychosocial effects of acne on adolescents and changes in quality of life and to reveal the differences – if any exist – of the effects between genders. The secondary aim was the investigation of the association between acne severity and quality of life, as well as psychosocial stress.

Materials and Methods

The present study included 164 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 years who were referred to the dermatology outpatient clinic. These individuals had been diagnosed with acne vulgaris but never referred to any doctor or treated for acne before. Adolescents with acne excoriee, other dermatological diseases or chronic medical and mental diseases were excluded from the study. The control group consisted of 188 healthy adolescents who did not have any acne on the body, had not been referred to a child and adolescent psychiatry department before and who were without any chronic medical and/or mental disease.

Acne severity of the patients was evaluated by the global acne grading system (GAGS). All patients filled in a Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI), Pediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire (PedsQL), and a Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The controls were asked to fill in the PedsQL and SDQ. The study was approved by Ethics Committee.

Global acne grading system

The GAGS is an acne grading system developed by Doshi et al.[10] In this grading system, lesions of acne vulgaris are divided into six sites: the forehead, right cheek, left cheek, nose, chin, and chest-back. Each site has one factor score: the forehead and nose are graded by one factor; the face and each cheek are graded by two factors and the chest and back are graded by three factors. Lesions are scored as follows: one point for a comedone, two points for a papule, three points for a pustule, and four points for a nodule. The lesion score of each site is calculated by the factor score, and the final score for that site is obtained. The total score varies between 1 and 44 and is evaluated as follows: mild falls between 1 and 18, moderate falls between 19 and 30, severe falls between 31 and 38, and very severe is over 39.

Pediatric quality of life questionnaire

The pediatric quality of life scale was developed to measure general quality of life in 2–18 years old.[11] The scale consists of four subscales where physical, emotional, social and school functionality aspects are investigated. The scoring is performed in three areas: total scale score (TSS); total score for physical health; and total score for psychosocial health, which includes calculation of the scores for emotional, social and school functionality.[12] The items are scored between 0 and 100. A higher total PedsQL score means a good perception of quality of life for overall health.[12] Furthermore, it should be noted that a study of PedsQL in Turkish for individuals 2–18 years of age proved it to be a reliable and valid scale.[13]

Strengths and difficulties questionnaire

The SDQ was developed to screen mental problems in children and adolescents.[14] It includes 25 questions that focus on positive and negative behavioral characteristics. These questions exist under five titles. These titles are behavioral problems, lack of attention and hyperactivity, emotional problems, and problems with peers and social behavior. Each title may be evaluated on its own, whereas a total score of difficulty may be calculated by addition of the 1st four titles. High scores in the area of social behavior reflect individual social strengths, and higher scores in the other four areas indicate severe difficulties. The scale was adopted into Turkish, and reliability and consistency were reported.[15]

Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index

The CDLQI was developed specifically for dermatology to measure quality of life in children.[16] The scale consists of ten questions that cover such topics as disease symptoms, emotions of the patients, spare time activities, school, holidays, human relations, sleep, and treatment. Total scores vary between 0 and 30, and a higher score indicates a decreased quality of life. A reliability and validity study of the scale in Turkish has been performed.[17]

Statistical analysis

Data obtained from the study were evaluated through SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) statistics software version 15. The variables obtained by measurement were expressed in mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables were expressed in percentages and numbers. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and histograms were examined to decide whether numerical variables show a normal distribution. Student's t-test was used for mean comparison between two groups with normal distribution, and a nonparametric test, Mann–Whitney U-test, was used for those without normal distribution. Categorical variables were evaluated by Pearson's Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was accepted as the limit for statistical significance.

For direction and level of the relation between numeric variables, Pearson's correlation test was used for variables with normal distribution, and Spearman's correlation test was used for variables without normal distribution.

Results

A total of 352 adolescents were enrolled in the study, including 59 boys and 105 girls in the case group and 72 boys and 116 girls in the control group. There was no significant difference between the two groups for gender (P = 0.563). The age averages of the case and control groups (mean ± standard deviation) were 15.7 ± 1.5 and 15.6 ± 0.9, respectively. The difference between age averages of two groups was not significant (P = 0.152).

The mean disease period for the case group was 26 ± 13 months. According to GAGS, the mean acne severity was 21.5 ± 7.4. Thirty-three percent of the patients had mild acne, while 57.1% had intermediate, 9% had severe, and 0.6% had very severe acne. There was no difference between genders for acne severity. The average score for the CDLQI, which was filled in by the case group only, was 8.1 ± 6.4.

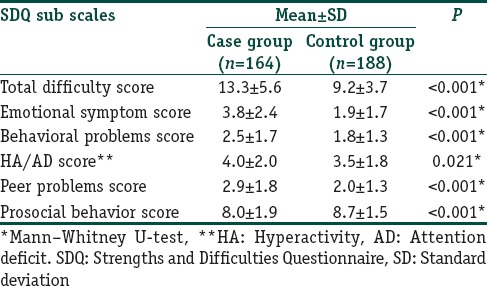

Since all subscale scores of the SDQ did not show normal distribution, they were compared through the Mann–Whitney U-test. All subscale scores of SDQ of the case group were significantly lower than the control group [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of subscale scores of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire between the case group and the control group

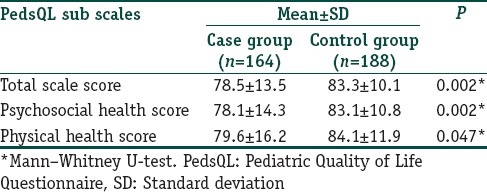

The physical health score, psychosocial health score and TSSs obtained from the PedsQL were significantly lower in the case group than the control group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of subscale scores of Pediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire between the case group and the control group

A significant correlation was detected between the total scores of CDLQI and PedsQL (P < 0.001) and the total SDQ difficulty score (P < 0.001). A less significant positive correlation existed between the total acne score in the case group calculated according to CDLQI and GAGS (P = 0.011).

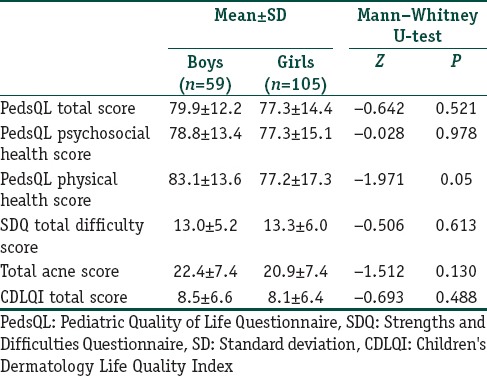

No significant difference was found between genders for all subscales of PedsQL and SDQ, total acne score and CDLQI [Table 3]. Furthermore, such scores were not correlated with age (P > 0.05).

Table 3.

Comparison of Pediatric Quality of Life Questionnaire, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, Acne severity and CDLQI scores for gender in case group

The case group was divided into two groups according to acne location, as the face (n = 103) and face-body-back (n = 61). No significant difference was found in PedsQL and SDQ subscales of the case group according to acne location (P > 0.05).

There was no correlation between total acne score and all subscales of PedsQL and SDQ when acne severity was evaluated as mild, intermediate, severe, and very severe in the case group (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The present study was performed to evaluate the quality of life in adolescents with acne, as well as to identify behavioral and emotional difficulties in that group and determine possible associated factors (severity, age, etc.). A total of 352 individuals, including 164 cases and 188 controls, were enrolled in the study. The case group had lower scores in all SDQ and PedsQL subscales. In addition, it was revealed that acne vulgaris, which may be defined as a simple disease, has a significant psychosocial effect on adolescent life. This result suggests that treatment of acne vulgaris is important.

One of the scales used to evaluate quality of life associated with the disease was PedsQL. In this scale, quality of life scores of the case group were lower, and life quality was worse. Patients with acne experience a serious decline in quality of life to the same extent as those with chronic diseases such as asthma, epilepsy, diabetes, back pain, or arthritis.[9] Moreover, previous studies have demonstrated that life quality is not correlated with acne severity as assessed by clinicians.[18,19] Even mild forms may have significant psychological effect on the patient.[20] In fact, a lack of correlation between acne severity and quality of life in the present study supports this finding. Adolescents with acne had significantly lower psychosocial health, physical health and TSSs, and this suggests that acne is an important factor for quality of life and affects individuals both physically and psychosocially.

Since acne appears on the face and during adolescence, adolescents may have difficulty establishing social relations during this period, when so much importance is placed on external appearance. Significantly lower scores in the prosocial behavior area of the SDQ subscale (which is used to determine psychosocial and behavioral difficulties of adolescents diagnosed with acne vulgaris) support this suggestion. Prosocial behavior may be defined as positive relations between individuals. Consequently, the issues identified with this type of behavior remind us that adolescents may have social difficulties due to acne. Such difficulties affect peer relations negatively. Higher total difficulty and emotional symptom scores suggest that general stress levels also increase. Significantly, lower peer problems scores from SDQ subscales, as compared to the control group, show that acne affects friend relations, which is one of the most important functionality fields during adolescence. When it is considered that peer victimization is frequently associated with external appearance,[21] adolescents with acne – particularly those with lesions on their face – may be exposed to peer victimization, and this may cause internalizing symptoms. Higher behavioral problem scores in the case group were taken as indicative of adolescents diagnosed with acne vulgaris presenting the psychological load as externalizing problems.

The mean CDLQI score of the case group was 8.5 indicating moderate impairment. This finding is in line with the studies where mean CDLQI values were found to be 7.5[13] in the UK and 8.9[22] in Thailand. No difference was found between acne severity and gender in the case group of the present study. Although some studies show that acne is more severe in boys[8,23] and some suggest that it is more severe in girls,[24] there are studies, as in this case, that found no difference between acne severity and genders.[25] The lack of difference in this study is thought to be related to the fact that it involved adolescents who were never treated because of acne vulgaris and were referred to the dermatology outpatient clinic for the first time. There was no difference between genders in the case group. In fact, community screening performed with adolescents found that acne is observed almost equally in both genders.[26,27] When the findings of our study were evaluated, boys and girls were affected equally from acne lesions and referred to the outpatient clinic with equal ratios.

The correlation between GAGS and CDLQI was poor. This finding was at par with that reported by Law et al.,[28] who showed no strong relation between the effects of acne severity and life quality. Furthermore, there was no correlation between acne severity and PedsQL and SDQ. The findings of the present study were interpreted as follows: Difficulties experienced in quality of life and psychosocial fields by adolescents with acne are independent of acne severity. Such difficulties may be associated with body perception rather than acne severity, and therefore, even mild lesions may cause strong effects on adolescents.

The mean period of acne in the case group was 26 months. Lesions lasting for over 1 year were present in 85% of the boys and 83% of the girls. This shows that adolescents do not get referred early for treatment.

The limitations of this study is that we evaluated the psychosocial status through self-reporting. A systematic psychiatric diagnostic through interview of the patients would have given a better assessment of the situation. However, it would have been a time-consuming endeavor and an expensive procedure.

Conclusion

The present study shows that acne has a significant effect on adolescents' quality of life and affects them psychosocially as well. Another important finding is that worsening in quality of life is not affected by factors such as duration, severity of acne and age. Even mild acne in adolescents may affect quality of life and cause psychosocial challenges. Beginning treatment of acne vulgaris as soon as possible may prevent psychological difficulties associated with the disease and help adolescents move forward in a healthy way.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

The worsening in quality of life is not affected by adolescents' age, severity, and duration of acne.

Clinicians should be aware of the impact of acne on adolescent's life and treat even mild forms of acne..

References

- 1.Hazarika N, Rajaprabha RK. Assessment of life quality index among patients with acne vulgaris in a suburban population. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:163–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.177758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lello J, Pearl A, Arroll B, Yallop J, Birchall NM. Prevalence of acne vulgaris in Auckland senior high school students. N Z Med J. 1995;108:287–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubba R, Bajaj AK, Thappa DM, Sharma R, Vedamurthy M, Dhar S, et al. Acne in india: Guidelines for management – IAA consensus document. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(Suppl 1):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levenson JL. Psychiatric issues in dermatology, part 3: Acne vulgaris and chronic idiopathic pruritus. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15:28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokandi A. Evaluation of acne quality of life and clinical severity in acne female adults. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:410809. doi: 10.1155/2010/410809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yazıcı K, Baz K, Yazıcı AE, Köktürk A, Tot S, Demirseren D, et al. Disease-specific quality of life is associated with anxiety and depression in patients with acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 204. 8:435–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Öztürkcan S, Aydemir Ö, İnanır I. Life quality in patients with acne vulgaris. Turk Klin J Dermatol. 2002;12:131–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aktan S, Ozmen E, Sanli B. Anxiety, depression, and nature of acne vulgaris in adolescents. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:354–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, Stewart-Brown SL, Ryan TJ, Finlay AY, et al. The quality of life in acne: A comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:672–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doshi A, Zaheer A, Stiller MJ. A comparison of current acne grading systems and proposal of a novel system. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:416–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The pedsQL: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care. 1999;37:126–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–12. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cakin Memik N, Aǧaoǧlu B, Coşkun A, Uneri OS, Karakaya I. The validity and reliability of the Turkish Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory for children 13-18 years old. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2007;18:353–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Güvenir T, Özbek A, Baykara B, Arkar H, Şentürk B, İncekaş S. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ) Turk J Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2008;15:65–74. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The children's dermatology life quality index (CDLQI): Initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balcı DD, Sangün Ö, İnandı T. Cross validation of the Turkish version of Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index. J Turk Acad Dermatol. 2007;1:71402a. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones-Caballero M, Chren MM, Soler B, Pedrosa E, Peñas PF. Quality of life in mild to moderate acne: Relationship to clinical severity and factors influencing change with treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:219–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demircay Z, Seckin D, Senol A, Demir F. Patient's perspective: An important issue not to be overlooked in assessing acne severity. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:181–4. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dreno B, Alirezai M, Auffret N, Beylot C, Chivot M, Daniel F, et al. Clinical and psychological correlation in acne: Use of the ECLA and CADI scales. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2007;134:451–5. doi: 10.1016/s0151-9638(07)89212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maynard H, Joseph S. Development of the multidimensional victimization scale. Agress Behav. 2000;26:169–78. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulthanan K, Jiamton S, Kittisarapong R. Dermatology life quality index in Thai patients with acne. Siriraj Med J. 2007;59:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanisah A, Omar K, Shah SA. Prevalence of acne and its impact on the quality of life in school-aged adolescents in Malaysia. J Prim Health Care. 2009;1:20–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jankovic S, Vukicevic J, Djordjevic S, Jankovic J, Marinkovic J. Quality of life among schoolchildren with acne: Results of a cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:454–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.98076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker N, Lewis-Jones MS. Quality of life and acne in Scottish adolescent schoolchildren: Use of the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) and the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, Lazarou D, Danopoulou I, Katsambas A, et al. The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. Results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:862–9. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uslu G, Sendur N, Uslu M, Savk E, Karaman G, Eskin M, et al. Acne: Prevalence, perceptions and effects on psychological health among adolescents in Aydin, Turkey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:462–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Law MP, Chuh AA, Lee A, Molinari N. Acne prevalence and beyond: Acne disability and its predictive factors among Chinese late adolescents in Hong Kong. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]