Sir,

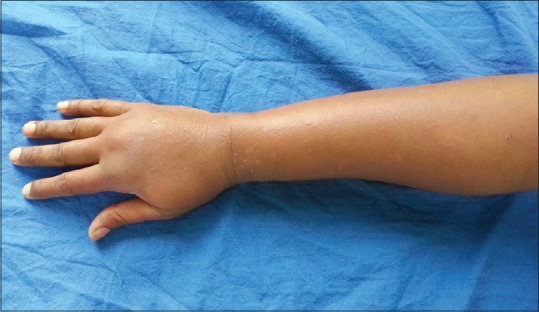

A 35-year-old female (para 1) presented with localized swelling topped with vesicles, diffuse redness, and itching over the right hand for the last 3 days. There was premenstrual periodic recurrence for the past 6 years starting after her delivery. The lesions subsided spontaneously 3–4 days postmenstruation. There was no history of rash elsewhere, lip or eye swelling, fever, drug ingestion, or other significant medical or surgical history. Cutaneous examination revealed an ill-defined, erythematous, slightly warm, tender edematous plaque topped with few 1–2 mm vesicles over the right hand and mid-forearm, without any lymphadenopathy [Figure 1]. A differential diagnosis of angioedema, cellulitis, and urticarial vasculitis was considered. Routine investigations such as complete blood count with eosinophil count, thyroid profile, sugar, and serum IgE level were within normal limits. Biopsy was refused. Ultrasonography of the lesion showed only mild subcutaneous edema without vascular or lymphatic abnormality.

Figure 1.

Swelling present over right hand with pinpoint vesicles

Considering the cyclic premenstrual recurrences, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis (AIPD) was considered and bedside progesterone provocation test was performed. To do the provocation test, 0.1 ml of 0.1% synthetic aqueous progesterone was injected intradermally on volar aspect of the left forearm. 0.1 ml of normal saline was injected as control. Photographs were taken at 0, 30, 60, and 120 min and 24 and 48 h. At 120 min, edema and erythema were appreciated at the injection site, and at 48 h, vesicles with coalescent bullae were ascertainable [Figures 2–4].

Figure 2.

Mild erythema was noted at site of progesterone injection after 2h

Figure 4.

At the end of 48 h, the vesicles coalesced to form bullae

Figure 3.

At the end of 24 h, vesicles were formed at the site of injection

With a final diagnosis of AIPD, the patient was given antihistamines with good response.

AIPD, a rare periodic dermatitis, is caused due to exogenous and/or endogenous progesterone (increased secretions in luteal phase). It subsides spontaneously postmenstrually. It can be seen in men rarely. Dermatitis can present variably as eczema, papulovesicular eruption, annular erythema, urticaria, angioedema, stomatitis, aphthous ulcers, erythema multiforme, folliculitis, fixed drug eruption, purpura, vulvovaginitis, pruritus, and anaphylaxis.[1,2] The exact etiology of AIPD is unknown and multiple hypotheses have been proposed:

Stimulation of T-helper cells due to exogenous progesterone therapy

Intolerance to high levels of progesterone occurring in pregnancy

Cross-sensitivity to other steroids

High expression of progesterone receptors

Type I hypersensitivity or Type IV hypersensitivity.

Warin has proposed the following diagnostic criteria[3]

Cyclic dermatitis in luteal phase

Positive intradermal progesterone provocation test

Prevention of the skin eruption by inhibiting ovulation.

In our patient, the first two criteria were fulfilled while the third one was not done.

Other investigations such as indirect immunofluorescence to detect circulating antibody to progesterone may be done. Histopathology is insignificant and shows hyperkeratosis with acanthosis and no eosinophils.

The treatment of AIPD is not standardized, but suppressing ovulation is the goal. First, exogenous progesterone if any has to be stopped. Low-dose oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) are drug of choice, but tamoxifen (anti-estrogen) and danazol (increased progesterone clearance) can also be used to avoid side effects of OCPs. Oral antihistamines have been used as in our case with partial or complete response. In patients undergoing in vitro fertilization, desensitization with increasing doses of progesterone can be tried until negative skin test is obtained.[2] In few cases, azathioprine and gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs such as nafarelin or leuprolide (ovulation suppressor) have been used with limited response. The definitive therapy in resistant cases is hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.[4]

AIPD, though rare, can present as the gamut of common clinical symptoms. Hence, a thorough history taking and high index of suspicion can aid in its diagnosis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hill JL, Carr TF. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis treated with a novel intramuscular progesterone desensitization protocol. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:537–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prieto-Garcia A, Sloane DE, Gargiulo AR, Feldweg AM, Castells M. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: Clinical presentation and management with progesterone desensitization for successful in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1121.e9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warin AP. Case 2. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kakarla N, Zurawin RK. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in an adolescent female. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:125–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]