Abstract

Introduction

Non-gestational choriocarcinoma (NGCC) is an extremely rare cancer. We report a case presenting in extremis.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman presented with type 1 respiratory failure with a 1-month history of breathlessness. Computed tomography (CT) revealed widespread metastatic disease involving the lungs, liver, pancreas, and breast. Serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin was markedly raised. Over 72 h, she deteriorated and was started on high-flow nasal cannula to facilitate discussions and for comfort. Histology from a breast biopsy suggested a choriocarcinoma, and she was commenced on etoposide and cisplatin. Unfortunately she continued to deteriorate and died on day 11 of admission. Molecular genotyping received post-mortem confirmed non-gestational choriocarcinomatous differentiation within a high-grade tumour.

Discussion

NGCC carries a worse prognosis compared with gestational choriocarcinoma and is historically less chemosensitive. However, differentiation between these two diagnoses is challenging due to a lack of immuno-histochemical differences. The NGCC in this case was likely to have originated in the lung due to a 12-cm mass in the lingula, and extensive emphysema on CT. Primary pulmonary choriocarcinoma has a rapidly fatal course in the majority of patients.

Conclusion

This is the only case to our knowledge of NGCC presenting in extremis, where an accurate diagnosis was not achieved pre-mortem. This also demonstrates the merit of non-invasive ventilation within palliation to facilitate communication and comfort.

Keywords: Non-gestational choriocarcinoma, Non-gestational trophoblastic disease, Lung cancer

Introduction

Non-gestational choriocarcinoma (NGCC) is an extremely rare tumour which carries a worse prognosis when compared with gestational choriocarcinoma (GCC) [1]. We report the case of a young female presenting in extremis with type 1 respiratory failure.

Case Report

A 39-year-old Caucasian female presented with acute respiratory distress with a 1-month history of shortness of breath and pleuritic chest pain. Past medical history included anxiety, depression, heavy smoking of both cigarettes and cannabinoids, and one successful pregnancy 16 years previously.

In addition to two discrete masses in the right breast, examination revealed a clear chest and upper abdominal tenderness. She was requiring 9 L of oxygen to maintain appropriate saturations.

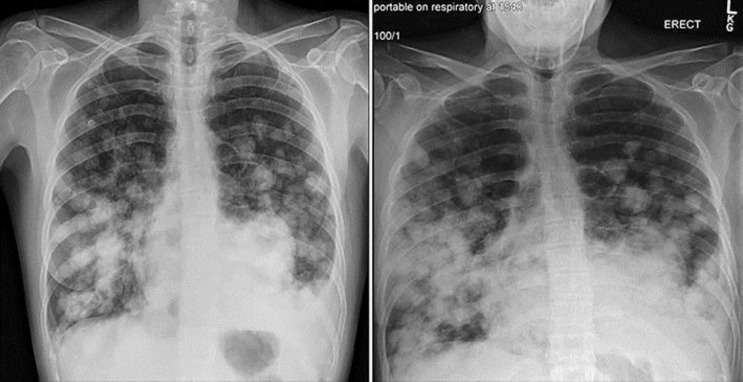

A chest X-ray displayed multiple opacifications suspicious for metastases and a left pleural effusion. Cross-sectional imaging reported extensive metastatic disease affecting the lung, liver, spleen, kidneys and pancreas, subcutaneous tissue in the right posterolateral chest, left flank and breast (Fig. 1). A dominant 12-cm mass in the lingula and evidence of marked emphysema for her age raised the possibility of a lung primary with extensive spread. Reproductive organs were reported as normal. A breast ultrasound revealed a 22 × 8 mm haematoma and a suspicious 12 × 11 mm lesion with increased vascularity, which was subsequently biopsied.

Fig. 1.

Left: chest X-ray from admission showing multiple lesions in both lungs. Right: chest X-ray 72 h post-admission.

Aside from a microcytic anaemia and a mildly raised alanine aminotransferase, routine blood tests were unremarkable. In view of her age and chest X-ray appearances, a urinary pregnancy test was performed to exclude trophoblastic disease, which was positive, prompting urgent tumour markers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Tumour markers from admission and normal ranges

| Blood test | Result | Normal range |

|---|---|---|

| LDH | 2,381 IU/L | 240–480 IU/L |

| AFP | 2.9 kIU/L | <5.8 kIU/L |

| hCG | 48,990 IU/L | <5 IU/L |

| CEA | 2.5 µg | <6.0 µg |

| CA-125 | 183 kU/L | <35 kU/L |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; hCG, human chorionic gonadotrophin; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA-125, cancer antigen 125.

Initial histological report suggested cohesive sheets of cells showing marked nuclear pleomorphism and moderate amounts of eosinophilia with focally clear cytoplasm. Scattered multinuclear giant cells were noted with large areas of necrosis although the typical biphasic pattern of choriocaricinoma was not prominent.

Immunohistochemistry received on day 5 of admission confirmed a carcinoma with strong expression of pancytokeratin (AE1/3, MNF116), CK7, CD10, P63 and showed focal positivity for human chorionic gonadroptropin (hCG). In addition to this, the tumour was negative for CK 20, CDX-2, S-100, ER, PR, thyroid transcription factor (TTF)-1, GCDFP-1, and PLAP. Differentials included GCC or choriocarinomatous differentiation in a carcinoma, with lung and breast being the most likely primaries. The pathology was sent to Charing Cross for a second opinion where molecular genotyping was requested.

The patient's respiratory function deteriorated significantly during the first 72 h of admission and she was initiated on nasal high-flow ventilation. A repeat chest X-ray at this time suggested disease progression as shown below (Fig. 2). On day 7, following notification from Charing Cross that the tumour could be consistent with a choriocarcinoma, chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide was commenced. After continued desaturation despite maximal non-invasive ventilation and increasing agitation, it was decided with the patient and her family to focus on symptom control. She sadly passed away on day 11 of admission. No post-mortem was undertaken.

Fig. 2.

CT imaging from admission showing multiple metastases in the lungs, liver, and spleen.

On day 40 after presentation, molecular genotyping confirmed a non-gestational trophoblastic tumour, with the absence of paternal alleles, resulting from choriocarcinomatous differentiation within a high-grade primary tumour.

Discussion

Choriocarcinoma is a rare, extremely malignant trophoblastic cancer characterised by the presence of two cell lines: cytotrophoblasts, which are primitive mononuclear trophoblastic stem cells, and syncytiotrophoblasts, which are multinucleated cells differentiating from the fusion of underlying cytotrophoblasts and secrete β-hCG [2]. The most common form of choriocarcinoma is gestational, arising from the trophoblast of any type of gestational event. It follows a hydatidiform mole, normal pregnancy or spontaneous abortion in decreasing frequency [3].

NGCCs are exceedingly rare, arising from pluripotent germ cells in the gonads or midline structures (for example, mediastinum) or in association with poorly differentiated somatic carcinomas [2]. Primaries reported include lung, cervix, endometrium, breast, bladder, and gastrointestinal tract [2, 4, 5, 6].

Accurate differentiation between GCC and NGCC is key, as NGCC carries a worse prognosis and is historically less chemosensitive [2]. GCCs are notorious for haematological spread with metastasis most often seen in the lungs (80%), pelvis, vagina, liver, kidneys, and spleen. NGCCs metastasise predominantly via the lymphatic system. As there are no distinctive immunohistochemical or microscopic differences between the two tumour types, delays in the diagnosis of NGCC are common, as seen in our case, particularly in women of childbearing age [7, 8]. DNA analysis and cytogenetics are therefore used to distinguish between the two entities; the exclusion of non-maternal DNA within the tumour confirms NGCC [8].

In this case, molecular genotyping performed at Charing Cross confirmed an NGCC, likely arising from a high-grade carcinoma. In a study of 438 patients with trophoblastic disease treated with EMA-CO (etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine) chemotherapy at Charing Cross Gestational Trophoblastic Disease Centre, 6 cases of NGCC were reported [1]. The majority (83%) arose from the lung (4 non-small cell, 1 small cell) and carried an extremely poor prognosis with 100% mortality as a result of drug-resistant disease [1]. This is compared with low- and high-risk gestational trophoblastic disease, with overall survival rates of 99.6 and 94.3%, respectively [1].

Low-dose induction chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin before EMA-CO has been found to reduce the risk of early death from rapid tumour destruction and haemorrhage (particularly within the thorax) compared with the use of full-dose chemotherapy. Although there are no randomised controlled trials to substantiate the superiority of EMA-CO chemotherapy over other regimens, it remains the gold standard of treatment in addition to surgical resection by trophoblastic centres in the UK [1].

The site of the primary neoplasm was not histologically confirmed in this case due to extensive metastatic spread and poor tumour differentiation. However, the clinical picture with presence of a 12-cm dominant mass in the lingula, underlying marked lung emphysema and smoking history suggests that the carcinoma was most likely to have originated in the lung. Furthermore, the patient had noticed abnormalities in her right breast 3 days before presentation, suggesting that these may have represented late metastases. Primary pulmonary choriocarcinomas exhibit strong cytoplasmic immunostaining for β-hCG and negativity for TTF-1, a marker for pulmonary epithelium (as seen in this case). In a review of 30 cases of primary pulmonary choriocarcinoma, the mean age of diagnosis was 30 years and demonstrated a rapidly fatal natural course in the majority of patients with a median survival of 1.8 years. Four of the cases reviewed had a similar disease course, not surviving beyond 2 weeks after presentation, with death resulting from respiratory compromise [9].

Given the survival differences between GCC and NGCC, if a diagnosis of NGCC had been made pre-mortem, it is unlikely that this patient would have received chemotherapy. Furthermore, given the extensive disease burden within the thorax and underlying emphysematous lung tissue, the likelihood of good residual respiratory function following chemotherapy was poor. However, given the speed of the respiratory decline, and knowing that without treatment there was no likelihood of surviving off ventilation or being discharged home, chemotherapy was justified accepting the expected outcome regardless of whether this was a gestational or non-gestational neoplasm.

As the patient deteriorated, high-flow nasal cannulae were used to control dyspnoea, maintain saturations and facilitate discussions.

Conclusion

This case discusses the rare clinical entity of metastatic NGCC arising from a high-grade carcinoma, and rare presentation of this; in extremis. This is the only case in the literature, to the best of our knowledge, where confirmed diagnosis of a primary NGCC was not achieved pre-mortem and clearly illustrates the difficulty in diagnosing NGCCs and initiating management without histological diagnosis.

Statement of Ethics

Consent from the patient's next of kin was obtained for this publication.

Disclosure Statement

There are no conflicting interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Pinias Mukonoweshuro for guidance with interpretation of the pathology involved in this case report.

References

- 1.Alifrangis C, Agarwal R, Short D, Fisher RA, Sebire NJ, Harvey R, et al. EMA/CO for high-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia good outcomes with induction low-dose etoposide-cisplatin and genetic analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jan;31((2)):280–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dilek S, Pata O, Tok E, Polat A. Extraovarian nongestational choriocarcinoma in a postmenopausal woman. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004 Sep–Oct;14((5)):1033–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.014548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramarajapalli ML, Rao NA, Murudaraju P, Kilara NG. Ovarian choriocarcinoma with concurrent metastases to the spleen and adrenal glands first case report. J Gynecol Surg. 2012;28((2)):153–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung, et al. Breast carcinoma with choriocarcinomatous features a case report. J Breast Cancer. 2013 Sep;16((3)):319–53. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.3.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen F, Tatsumi A, Numoto S. Combined choriocarcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the lung occurring in a man case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 2001 Jan;91((1)):123–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1<123::aid-cncr16>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maehira H, Shimizu T, Sonoda H, Mekata E, Yamaguchi T, Miyake T, et al. A rare case of primary choriocarcinoma in the sigmoid colon. World J Gastroenterol. 2013 Oct;19((39)):6683–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i39.6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yadav BS, Rai B, Suri V, Mukherjee KK, Bal A, Morgan R, et al. A Young Female With Metastatic Nongestational Choriocarcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2015 Dec;42((6)):e109–15. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher RA, Newlands ES, Jeffreys AJ, Boxer GM, Begent RH, Rustin GJ, et al. Gestational and nongestational trophoblastic tumors distinguished by DNA analysis. Cancer. 1992 Feb;69((3)):839–45. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920201)69:3<839::aid-cncr2820690336>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kini, et al. Primary Pulmonary Choriocarcinoma: Is It Still an Enigma? Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2007;49:219–26. [Google Scholar]