Abstract

Valproic acid (VPA) plays a role in histone modifications that eventually inhibit the activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC), and will affect the expressions of genes Pdx1, Nkx6.1, and Ngn3 during pancreatic organogenesis. This experiment was designed to study the effect of VPA exposure in pregnant rats on the activity of HDAC that controls the expression of genes regulating the development of beta cells in the pancreas to synthesize and secrete insulin. This study used 30 pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats, divided into 4 groups, as follows: (1) a control group of pregnant rats without VPA administration, (2) pregnant rats administered with 250 mg VPA on day 10 of pregnancy, (3) pregnant rats administered with 250 mg VPA on day 13 of pregnancy, and (4) pregnant rats administered with 250 mg VPA on day 16 of pregnancy. Eighty-four newborn rats born to control rats and rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy were used to measure serum glucose, insulin, DNA, RNA, and ratio of RNA/DNA concentrations in the pancreas and to observe the microscopical condition of the pancreas at the ages of 4 to 32 weeks postpartum with 4-week intervals. The results showed that at the age of 32 weeks, the offspring of pregnant rats administered with 250 mg VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy had higher serum glucose concentrations and lower serum insulin concentrations, followed by decreased concentrations of RNA, and the ratio of RNA/DNA in the pancreas. Microscopical observations showed that the pancreas of the rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA during pregnancy had low immunoreaction to insulin. The exposure of pregnant rats to VPA during pregnancy disturbs organogenesis of the pancreas of the embryos that eventually disturb the insulin production in the beta cells indicated by the decreased insulin secretion during postnatal life.

Keywords: Valproic acid, Histone deacetylase, Gene expression, Pancreas organogenesis, Insulin, Rat

INTRODUCTION

The beta cells are cells that play a role in the synthesis and secretion of insulin (1). A defect in the development of beta cells during organogenesis will affect the capacity and ability of beta cells to synthesise and secrete insulin (2). Insulin plays a role in facilitating glucose transport from the circulation into the cells to maintain a normal blood glucose concentration (3). A decrease in insulin secretion, malfunction of insulin receptors, or a combination of both (4) can lead to hyperglycaemia, which is a sign of diabetes mellitus, especially type 2 diabetes mellitus (5). Generally, when the diagnosis is made, the functional capacity of beta cells has decreased to the level of 30% to 50% of the original capacity (6).

The growth and development of the pancreas are regulated by a specific control molecule derived from the differentiation of progenitor cells and are influenced by the signalling and transcription pathways (2). The development of the pancreas consists of two transitional regulations that begin on day embryonic day 8.75 to day 12.5, with the formation of buds on the endoderm layer and proliferation of the cells followed by a quick cell growth that eventually increases the size of the cells. In the growth of the pancreas, there is a change in the morphogenesis of tubular structures called the primary transition. In this primary transition, the epithelial cells have not yet undergone the process of differentiation (7). In the secondary transition regulation, the epithelial cells of the pancreas expand the branching followed by the process of differentiation of endocrine cells, acinar cells, and ducts, which occurs on embryonic day 12.5 to birth (8).

The exposure of embryos to valproic acid (VPA) during this embryonic stage of pregnancy can interfere with the expression of genes that play a role in the development of the pancreas, such as the Pdx1, Nkx6.1, and Ngn3 genes (9). The Pdx1 gene acts as the central onset of the signaling complex and transcriptional regulation tissue that regulate the proliferation and differentiation of the pancreas (9). The Nkx6.1 gene controls the branching of the tip and trunk portion of the pancreas. The tip will develop into the exocrine pancreas, whereas the trunk will develop into the endocrine pancreas. The Ngn3 gene plays a role in expressing progenitor cells during the development of pancreatic beta cells (10).

Exposure of the embryos to VPA during pregnancy, especially during organogenesis, can cause abnormalities in the structure and function of the pancreas that are expressed after birth (11). The abnormalities occur because of specific factors that affect the proliferation and differentiation of cells during embryonic development (12). VPA is an antiepileptic drug that affects histone modifications during cell proliferation and differentiation by affecting the activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) (13). Structural modifications of histones can be made by acetylation or de-acetylation, which are important in modulating gene expression (14), and are activated or repressed by histone acetyl transferase (HAT) and HDAC, respectively. HAT enzymes loosen the DNA conformation, which causes the facilitation of gene transcription (activation), whereas HDAC tightens the DNA conformation, which causes inactivation of gene transcription (repression) (15). The purpose of this study is to investigate the ability of VPA to inhibit organogenesis of the fetus, and the effects on the development of pancreatic beta cells, which play a role in the synthesis of insulin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Thirty female Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from the Animal Maintenance Unit of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Bogor Agricultural University. The experimental rats used were aged 3 to 4 months and had a body weight of 200 to 250 g. The experimental rats were injected with PGF2α (Noroprost®, Hyperdrug Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Durham, North East England) to synchronise the estrous cycle. After synchronisation, the experimental rats were mixed with male rats, and vaginal swabs were used to detect sperm to determine day 0 of pregnancy.

Treatment

During pregnancy, the experimental female rats were separated from male rats and grouped into 4 treatment groups. The first group was the pregnant experimental rats without administration of VPA (control group, T0). The second group was the pregnant experimental rats administered with VPA (Depakote, Abbott Laboratories) in a single dose of 250 mg orally on day 10 of gestation, coinciding with the Pdx1 gene expression (T1). The third group was the pregnant experimental rats administered with VPA in a single dose of 250 mg orally on day 13 of gestation coinciding with the expression of the Nkx6.1 gene (T2). The fourth group was the pregnant experimental rats administered with VPA in a single dose of 250 mg orally on day 16 of gestation coinciding with the expression of the Ngn3 gene (T3). The rats were maintained during pregnancy. After birth, the offspring were maintained with their maternal rats for 4 weeks postpartum. At the age of 4 weeks, the offspring were separated from their maternal rats. A total of 84 offspring rats were used in the experiment. The offspring were euthanised at the ages of 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 32 weeks, respectively. The pancreas was isolated for measurement of insulin secretion in the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas (beta cells) by immunoreaction to insulin and glucagon. Concentrations of DNA, RNA, and the ratio of RNA/DNA in the pancreas of the offspring rats were also measured. Blood samples were collected to measure serum concentrations of insulin and glucose in the offspring. The experiment was conducted according to the Animal Ethics issued by the Department of Pathology of Bogor Agricultural University (SKEH Number: 031/KEH/SKE/IV/2015).

Preparation of specimens

Prior to organ harvesting, 84 experimental offspring rats were anaesthetised with a combination of ketamine and xylazine. Once the rat was deeply anaesthetised, the pancreatic organs were harvested, and the organs were cleaned using physiological saline.

Measurements of DNA and RNA concentrations in the pancreatic tissue

DNA and RNA from the pancreas of 84 offspring rats were measured using 0.5 to 1 g of pancreatic tissue. The samples were dried in an oven at 60°C for 3 days; then, the dried pancreas tissue was crushed into powder. Concentrations of DNA and RNA in the pancreatic tissue were determined using the Genomic DNA Mini Kit (tissue) and a total RNA Mini Kit (tissue), respectively, by following the manufacturer’s instructions (Geneaid, PT Genetics Science, Jakarta, Indonesia).

Measurements of serum insulin and glucose concentrations

The serum glucose concentrations of the offspring rats were measured by the enzymatic colorimetric method using glucose/GOD-PAP kits (Human Co. Ltd., Wiesbaden, Germany). Serum insulin concentrations were measured by enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA), using RayBio Rat Insulin ELISA Kit Catalog #: ELR-Insulin (RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, Greece).

Immunohistochemistry

The preparation of histology for pancreatic organs, photography, and the reading of the preparations were conducted in the Pathology Laboratory and the Histology Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Bogor Agricultural University. Preparations of paraffinised pancreatic tissue were deparaffinised with xylol and rehydrated with graded alcohol and water. Most preparations were stained by immunohistochemistry (IHC) by following the manufacturer’s instructions (Biozatix, PTBiozatix, Jakarta, Indonesia) for insulin and glucagon. Observation of immunohistochemical preparation was conducted using a light microscope (Olympus, Luzhou, Taipei).

Statistical analysis

The collected data on glucose, insulin, DNA, RNA, and ratio of RNA/DNA concentrations of the offspring rats were analysed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). All of the data analysis was done by the general linear model procedure in SPSS version 23. Results were expressed as mean standard deviation (SD); if there was a specific difference (p < 0.05) in the mean of each group, the Duncan pos-hoc test was conducted (16). Qualitative analysis of the microscopic feature of immunohistochemistry staining was performed using a light microscope (Olympus).

RESULTS

DNA concentrations

The exposure of embryos to VPA during organogenesis affects the cell cycle process, thereby inhibiting the proliferation and differentiation of pancreatic cells, as shown by the low concentration of pancreatic DNA of the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with 250 mg VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy. Concentrations of pancreatic DNA are summarized in Table 1. The decrease in pancreatic DNA concentrations of offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy was found consistently at the ages of 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks postpartum. At the age of 32 weeks, even though it was not significantly different, DNA concentration of the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on days 10 (7.81 ± 0.39 μg/mg) and 16 (7.92 ± 0.06 μg/mg) was numerically lower compared with those born to pregnant rats without administration of VPA (8.11 ± 0.56 μg/mg). The offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy (8.36 ± 0.00 μg/mg) was higher compared with those born to pregnant rats without administration of VPA.

Table 1.

Concentrations of DNA, RNA, and ratio of RNA/DNA in the pancreas of offspring

| Parameter | Time (weeks) (n = 3) | Group (mean value ± SD) | ANOVA (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |||

| DNA concentration (μg/mg) | 4 | 9.27 ± 1.05 | 7.85 ± 0.39 | 8.20 ± 0.09 | 8.66 ± 0.01 | 0.066 |

| 8 | 8.76 ± 0.48a | 8.39 ± 0.09ab | 8.09 ± 0.28b | 8.32 ± 0.00ab | 0.010 | |

| 12 | 8.84 ± 0.54 | 8.10 ± 0.49 | 8.27 ± 0.09 | 8.09 ± 0.15 | 0.118 | |

| 16 | 9.16 ± 0.60a | 8.39 ± 0.08b | 8.19 ± 0.09b | 8.09 ± 0.09b | 0.011 | |

| 20 | 8.69 ± 0.36a | 8.52 ± 0.15ab | 7.45 ± 0.02c | 8.18 ± 0.09b | 0.000 | |

| 24 | 8.43 ± 0.48a | 7.64 ± 0.33b | 8.13 ± 0.13ab | 8.31 ± 0.06a | 0.051 | |

| 32 | 8.11 ± 0.56 | 7.81 ± 0.39 | 8.36 ± 0.00 | 7.92 ± 0.06 | 0.284 | |

|

| ||||||

| RNA concentration (μg/mg) | 4 | 10.85 ± 0.71a | 10.06 ± 0.00ab | 10.82 ± 0.20a | 9.83 ± 0.44b | 0.041 |

| 8 | 10.66 ± 0.39a | 10.13 ± 0.07b | 10.25 ± 0.23ab | 10.02 ± 0.12b | 0.049 | |

| 12 | 11.01 ± 0.27a | 9.48 ± 0.03d | 10.29 ± 0.05c | 10.68 ± 0.13b | 0.000 | |

| 16 | 10.87 ± 0.50a | 9.50 ± 0.00c | 10.19 ± 0.04b | 10.73 ± 0.21a | 0.001 | |

| 20 | 11.16 ± 0.53a | 9.41 ± 0.16c | 8.99 ± 0.17c | 10.02 ± 0.12b | 0.000 | |

| 24 | 12.65 ± 0.25a | 9.44 ± 0.11c | 10.12 ± 0.09b | 10.14 ± 0.31b | 0.000 | |

| 32 | 12.33 ± 0.79a | 9.43 ± 0.11b | 10.08 ± 0.10b | 10.03 ± 0.55b | 0.000 | |

|

| ||||||

| Ratio RNA/DNA concentration (μg/mg) | 4 | 1.18 ± 0.11bc | 1.28 ± 0.06ab | 1.32 ± 0.01a | 1.14 ± 0.05c | 0.038 |

| 8 | 1.22 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | 1.27 ± 0.04 | 1.21 ± 0.01 | 0.213 | |

| 12 | 1.25 ± 0.08 | 1.17 ± 0.07 | 1.24 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.03 | 0.078 | |

| 16 | 1.19 ± 0.13ab | 1.13 ± 0.02c | 1.24 ± 0.01ab | 1.33 ± 0.04a | 0.047 | |

| 20 | 1.28 ± 0.03a | 1.10 ± 0.04c | 1.21 ± 0.02b | 1.23 ± 0.02b | 0.000 | |

| 24 | 1.50 ± 0.10a | 1.24 ± 0.06b | 1.25 ± 0.02b | 1.22 ± 0.04b | 0.002 | |

| 32 | 1.53 ± 0.16a | 1.21 ± 0.06b | 1.21 ± 0.01b | 1.27 ± 0.07b | 0.012 | |

Different superscripts in the same row indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to verify the differences between the average treatment and the control treatment obtained from the test results.

RNA concentrations

The decreased DNA concentration was followed by a decrease in RNA concentration in the pancreas of the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy. At the ages of 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 32 weeks postpartum, pancreatic RNA concentrations of offspring rats born to experimental pregnant rats administered with VPA were lower compared with offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration. The decrease in pancreatic RNA concentrations in offspring rats born to experimental pregnant rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy was evident during the period of 32 weeks postpartum (9.43 ± 0.11 μg/mg, 10.08 ± 0.10 μg/mg, and 10.03 ± 0.55 μg/mg, respectively), compared with control offspring rats (12.33 ± 0.79 μg/mg) (Table 1).

Ratio of RNA/DNA concentrations

Ratio of RNA/DNA concentrations. The ratios of RNA/DNA in the pancreas of offspring rats at the age of 4 weeks postpartum were different (p < 0.038), and the highest ratios were found in the offspring rats born to the experimental pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy, followed by those born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 10, control offspring rats, and those born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy. At the ages of 12 and 16 weeks postpartum, the highest ratios of RNA/DNA were found in the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy followed by those born to control pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy. At the ages of 20, 24, and 32 weeks postpartum, the highest RNA/DNA ratio was found in the experimental offspring rats born to pregnant rats without VPA administration. At the age of 32 weeks postpartum, the ratio of RNA/DNA in the pancreas of offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration, and those administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy, were 1.53 ± 0.16 μg/mg, 1.21 ± 0.06 μg/mg, 1.21 ± 0.01 μg/mg, and 1.27 ± 0.07 μg/mg, respectively (Table 1).

The ratio of RNA/DNA in the pancreas of offspring rats at the age of 4 weeks postpartum were different (p < 0.038), and the highest ratios were found in the offspring rats born to the experimental pregnant rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy, followed by those born to rats administered with VPA on day 10 pregnancy, control offspring rats, and those born to rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy. At the ages of 12 and 16 weeks postpartum, the highest ratio of RNA/DNA was found in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy followed by those born to control rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy. At the ages of 20, 24, and 32 weeks postpartum, the lowest RNA/DNA ratio was found in the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA compared with offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration. At the age of 32 weeks postpartum, the ratio of RNA/DNA in the pancreas of offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration, and those administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy, were 1.53 ± 0.16 μg/mg, 1.21 ± 0.06 μg/mg, 1.21 ± 0.01 μg/mg, and 1.27 ± 0.07 μg/mg, respectively (Table 1).

Serum insulin and glucose concentrations

The ability of VPA to affect gene expression during organogenesis results in a decrease in the ability of RNA to synthesise proteins, which was seen in the low pancreatic insulin concentrations. Serum insulin concentrations at the ages of 4 and 8 weeks postpartum were found to be lower in the offspring rats born to rats administered with all doses of VPA during pregnancy compared with control offspring rats. The lower serum insulin concentrations in the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA were also associated with the lowest concentrations of pancreatic DNA and RNA, and the highest serum glucose concentration. Serum insulin and glucose concentrations of the offspring rats are shown in Table 2. At the age of 12 weeks postpartum, there was an increase in insulin concentration in the experimental offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy (10.94 ± 0.69 μIU/mL), resulting in a decrease in glucose levels (108.80 ± 5.14 mg/dL), which was almost equal to glucose concentrations in the offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration, but lower than those born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 and 16 of pregnancy (126.76 ± 0.58 μIU/mL and 135.33 ± 12.85 μIU/mL, respectively). At the age of 16 weeks postpartum, a lower insulin concentration was found in the offspring rats born to pregnant rats without administered with VPA (5.70 ± 0.96 μIU/mL). The serum insulin concentrations in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy decreased from 10.94 ± 0.69 μIU/mL to 9.73 ± 2.14 μIU/mL, resulting in increasing blood glucose concentrations from 108.80 ± 5.14 mg/dL to 143.00 ± 11.36 mg/dL. At the age of 20 weeks postpartum, the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy showed an increased insulin concentration (p < 0.00) (20.55 ± 0.36 μIU/mL) compared with the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 and 13 of pregnancy. The increase in serum insulin concentrations in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy was associated with a lower serum glucose concentration (114.64 ± 7.40 mg/dL) compared with offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 and 13 of pregnancy and those born to control maternal rats without VPA administration.

Table 2.

Concentrations of insulin and glucose in offspring

| Parameter | Time (weeks) (n = 3) | Group (mean value ± SD) | ANOVA (p) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |||

| Insulin concentration (μIU/mL) | 4 | 16.42 ± 1.33a | 5.18 ± 0.55b | 4.59 ± 0.05b | 4.36 ± 0.72b | 0.000 |

| 8 | 8.15 ± 1.96a | 5.39 ± 1.01b | 3.97 ± 0.43b | 4.49 ± 0.41b | 0.009 | |

| 12 | 7.03 ± 0.32b | 7.06 ± 1.02b | 10.94 ± 0.69a | 4.06 ± 1.06c | 0.000 | |

| 16 | 5.70 ± 0.96c | 8.39 ± 0.97ab | 9.73 ± 2.14a | 6.64 ± 0.82bc | 0.025 | |

| 20 | 3.36 ± 0.71b | 4.23 ± 0.50b | 4.09 ± 0.23b | 20.55 ± 0.36a | 0.000 | |

| 24 | 30.73 ± 1.09a | 3.94 ± 0.82c | 7.18 ± 0.45b | 3.45 ± 0.15c | 0.000 | |

| 32 | 7.91 ± 0.17a | 3.68 ± 0.05b | 2.77 ± 0.64d | 3.27 ± 0.05c | 0.000 | |

|

| ||||||

| Glucose concentration (mg/dL) | 4 | 101.00 ± 7.81b | 143.67 ± 17.21a | 147.78 ± 17.40a | 130.10 ± 15.19a | 0.019 |

| 8 | 98.50 ± 9.34b | 134.00 ± 6.73a | 157.00 ± 21.36a | 141.02 ± 13.22a | 0.005 | |

| 12 | 107.98 ± 9.11b | 126.76 ± 0.58a | 108.80 ± 5.14b | 135.33 ± 12.85a | 0.009 | |

| 16 | 117.70 ± 1.09b | 125.67 ± 2.75b | 143.00 ± 11.36a | 144.69 ± 11.91a | 0.010 | |

| 20 | 117.75 ± 0.25b | 166.51 ± 25.06a | 139.50 ± 13.81ab | 114.64 ± 7.40b | 0.009 | |

| 24 | 105.50 ± 14.30b | 168.17 ± 3.15a | 161.26 ± 11.53a | 151.40 ± 6.52a | 0.000 | |

| 32 | 120.50 ± 1.73c | 186.10 ± 20.65b | 214.85 ± 13.82a | 178.93 ± 7.21b | 0.000 | |

Different superscripts in the same row indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to verify the differences between the average treatment and the control treatment obtained from the test results.

At the age of 24 weeks postpartum, serum insulin concentrations increased significantly (p < 0.00) in control rats (30.73 ± 1.09 μIU/mL) compared with the other ages. This significant increase in serum insulin concentration was reflected in the decreased serum glucose concentrations (105.50 ± 14.30 mg/dL).Therefore, at the age of 24 weeks postpartum, the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy had lower serum insulin concentrations with higher serum glucose concentrations compared with the control offspring rats. At the age of 32 weeks postpartum, insulin concentrations in control offspring rats born to pregnant rats without VPA administration were decreased (7.91 ± 0.17 μIU/mL) (p < 0.00). However, serum insulin concentration of the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA were lower compared with those of control offspring rats (Table 2).

Increased serum insulin concentrations in all groups of offspring rats occurred at different growth periods. At the age of 12 weeks postpartum, the highest concentration of insulin was found in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy. At the age of 16 weeks postpartum, serum insulin concentrations in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 10 of pregnancy were increased, whereas at the age of 20 weeks postpartum, the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy showed the highest serum insulin concentrations. Serum insulin concentrations changed at different growth periods in each of the maternal groups.

Serum glucose concentrations in the offspring rats had a negative correlation with serum insulin concentrations. The decreased insulin concentrations increased blood glucose concentrations. At the age of 32 weeks postpartum, serum glucose concentrations in the control offspring rats born to pregnant rats without VPA administration and those born to rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy were consistently higher (Table 2).

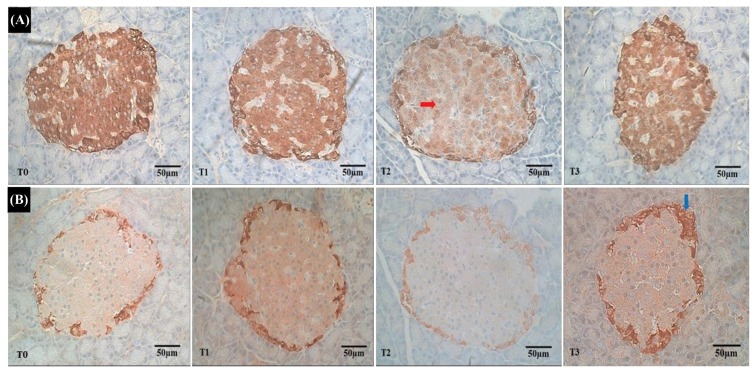

Immunohistochemical measurement

The observations of immunohistochemical staining of pancreatic tissue in all experimental offspring rats were conducted by looking at the population of beta cells and alpha cells. The results of immunoreactive observation showed that insulin and glucagon concentrations in the beta and alpha cells underwent dynamic changes during 32 weeks of postnatal life. At the age of 32 weeks postpartum, the beta cells in offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy, showed low immunoreactions to insulin compared with the beta cells in offspring rats born to pregnant rats without administration of VPA, which showed a high immunoreactivity to insulin (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Immunoreactivity on the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas of the offspring rat. (A) Represents the immunoreactivity to insulin levels from the islets of Langerhans of the pancreas of offspring rat. Representative images of these levels of immunoreactivity to insulin from the control group (T0), and islets of Langerhans in the treatment group on day 10, day 13, and day 16 of gestation (T1, T2, and T3) showed a low immunoreactivity to insulin (red arrow). (B) Represents the immunoreactivity to glucagon levels from the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas of an offspring rat. Representative images of these levels of immunoreactivity to glucagon from the control group (T0), and islets of Langerhans in the treatment group on day 10, day 13, and day 16 of gestation, (T2, and T3), showed a high immunoreactivity to glucagon (blue arrow) on day 16 of gestation (T3).

In immunoreaction to insulin imaging, the insulin concentrations in the pancreas of offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 (T1) and 16 (T3) of pregnancy had lower immunoreaction to insulin compared with the controlled rats born to pregnant rats without VPA administration (T0), but higher immunoreaction to insulin compared with the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 13 of pregnancy (T2) (Fig. 1A).

At the age of 32 weeks postpartum, with regard to immunoreaction to glucagon imaging, the glucagon concentrations in the pancreas of offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 (T1) and 13 (T2) of pregnancy had higher immunoreaction to glucagon than the control rats born to pregnant rats without VPA administration, but immunoreaction to glucagon was higher on day 16 gestation (T3) compared with the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 10 (T1) and day 13 (T2) of pregnancy (Fig. 1B).

DISCUSSION

VPA is an anticonvulsant drug with a broad spectrum in the treatment of epilepsy (17). The use of VPA during pregnancy is known to cause a congenital malformation (18). This effect is due to the ability of VPA to bind plasma protein (approximately 80~94%) (19), and protein-bound VPA can be transferred into the developing embryo through the placenta, both in animals and humans (20). The organs developing during the exposure of the embryo to VPA will be the targets of disruption (21). In addition to the stage of exposure, the dose, the route of delivery, as well as the type of compound itself affects the susceptibility of the organ to disorder (22). It was concluded that the embryo damage is formed by multiple factors contributed to by both environmental and genetic factors (23).

The administration of VPA and the exposure of embryos to VPA can interfere with cell cycle processes during organogenesis that can affect cell proliferation and differentiation (24), which is shown by the low concentrations of DNA and RNA in the experimental offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA, compared with the control experimental offspring rats born to rats with-out exposure to VPA during pregnancy. The results of DNA analysis in the offspring rats born to pregnant rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy showed a disruption in the cell cycle, through the G1 checkpoint, so that the cell could not proceed to phase S for DNA synthesis, resulting in the inhibition of organogenesis or uncontrolled cell proliferation that eventually induced oncogenesis (25).

VPA works by inhibiting the activity of HDAC (26), one of the histone modifications that play a role in epigenesis (27). VPA initiated by hyper-acetylation of histone DNA (13,28,29) leads to hyper-acetylation in H4K16 (30). Hyper-acetylation also occurs in H3K9, H3K14, H4K5, and H4K12 (31). Hyper-acetylation is one of the responses to DNA damage (32). When DNA damage is detected, it will generate cell sensors, such as ATM and ATR, and activate various pathways. The main pathway is kinase, which phosphorylates several targets including p53, which is previously in an inactive state that binds to MDM2 (p53 inhibitor) at the time of phosphorylation. The binding of MDM2 to phosphate makes this molecule inactive. However, the binding of p53 to phosphate causes this molecule to be activated (33), and induces transactivation of p21 (Cip1/Waf1), which binds G1-specific cyclin-CDK complex and acts as a CDK inhibitor causing pRB to remain bound to the E2F transcription factor; thus, there is no transition of the cell cycle from G1 to S phase, and no cell proliferation and differentiation (34).

The damage of DNA leads to the instability of RNA synthesis (35), leading to a decrease in the ability of RNA to synthesise proteins. The high concentration of RNA indicates the high activity of genetic transcription of DNA into RNA synthesis. If RNA is synthesised actively, then the cells will grow faster. Therefore, the cell growth rate is strongly associated with the ratio of RNA/DNA, which is a form of expression of cell growth character in tissues.

At the age of 4 weeks postpartum, the ratios of RNA/DNA in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 and 13 of pregnancy were high compared with those of control offspring rats without exposure to VPA during pregnancy. This result illustrates the ability of the experimental rats to grow well by increasing their ability to synthesise RNA at low DNA concentrations, compared with control animals, which have a balance of DNA concentration with high RNA synthesis capability. The RNA/DNA ratio is used to measure growth based on the assumption that the amount of DNA, the main carrier of genetic information, is stable under the changing environmental condition in somatic cells of a species. However, the amount of RNA is directly involved in protein synthesis, which varies according to the life stages and sizes of the organism in response to changes in environmental conditions. At the age of 4 weeks postpartum, the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 and 13 of pregnancy had good growth capabilities in environmental changes due to the administration of VPA during pregnancy by increasing RNA synthesis (36).

At the ages of 20, 24, and 32 weeks postpartum, it was found that the ratio of RNA/DNA in the offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration during pregnancy were higher compared with those of the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy. The results showed that the offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration during pregnancy had good pancreas development during embryonic growth. Growth is demonstrated by the intensive protein synthesis during the active cell growth and enlargement (37), indicated by constant concentrations of DNA. However, an increase in the RNA/DNA ratio in the organ or tissue is an indicator of the protein- synthesis potential of a cell (38).

The ability of VPA to influence organogenesis of insulin- producing beta cells is shown by the decreased RNA concentrations, which directly illustrates the decrease in protein synthesis (39). This condition was demonstrated by the low insulin concentrations in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy at the age of 32 weeks postpartum compared with the control offspring rats born to pregnant rats without VPA administration during pregnancy.

The increased insulin concentrations in each treatment occur in different growth periods, indicating the ability of beta cells to increase insulin secretion by releasing proinsulin to decrease glucose concentrations. The increase in pro-insulin secretion is associated with the dysfunction and loss of beta cells of the pancreas (40). Hyper-pro-insulin-aemia is expressed as an effect of beta cell breakdown, which is indicated by hyperglycaemia. In long-term studies, the measurements of insulin and pro-insulin secretions and concentrations could be used as independent predictors of type 2 diabetes (41).

Blood glucose concentrations are regulated by insulin through the mechanism of glucose transport or absorption capacity from circulating blood into the using tissues, thereby lowering blood glucose concentrations (42). Low or reduced insulin concentration in the circulation could be caused by the dysfunction of pancreatic beta cells or high glucose uptake in peripheral tissue, or both, leading to early abnormalities in peripheral tissue (insulin resistance) and subsequently followed by pancreatic beta cell dysfunction (43). The increased blood glucose concentration is a major factor that stimulates beta cells to synthesise and secrete insulin.

Immunoreaction observation of glucagon in alpha cells showed that the distribution of alpha cells in the pancreas was higher in the offspring rats born to control pregnant rats without VPA administration during pregnancy, indicated by the presence of alpha cells in the peripheral part of the islets of Langerhans. In the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy, the number of immunoreactive cells to glucagon and the number of alpha cells were higher compared with the control group. These increased parameters can be correlated with the increased DNA concentrations at the ages of 16, 20, and 32 weeks postpartum in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on days 10 and 13 of pregnancy, that were supposed to be due to the disruption of transitional development from alpha cells to beta cells (6).

The presence of impaired insulin concentrations indicates that the enlargement of beta cell diameter is caused by a compensatory mechanism due to insulin resistance conditions (44), with immunohistochemical features showing relatively less dense and smaller beta cells as an indicator of decreased density of beta cells. The interspersed nature of beta cells within the other, non-beta cells further demonstrates the expansive and intrusive conditions of alpha cells toward the central part, suggesting an increase in the number of alpha cells (45,46). The expansive and intrusive conditions of alpha cells were observed in the microscopic photo of the pancreas in the offspring rats born to rats administered with VPA on day 16 of pregnancy.

The administration of VPA on days 10, 13, and 16 of pregnancy is associated with gene expression that plays a role in the development of the pancreas, especially pancreatic beta cells. The administration of VPA on day 10 of pregnancy is associated with the expression of the Pdx1 gene, which plays an important role in the early steps of pancreatic development (47). The day 13 of pregnancy is associated with the expression of the Nkx6.1 gene, which plays a role in beta cell neogenesis through trans-differentiation of pancreatic progenitor cells; and, this process determines the number of beta cells at birth (48). Day 16 of pregnancy is associated with the expression of the Ngn3 gene that plays a role in the formation of the islets of Langerhans (49), and the differentiation of the pancreatic endocrine region associated with the production of insulin (50). Pdx1and Nkx6.1 gene expressions occur in the critical period of organogenesis, causing a greater damage than was expressed by the Ngn3 gene after a critical period.

The inhibitory activity of HDAC by VPA may affect the process of pancreatic organogenesis of offspring during pregnancy. VPA works by inhibiting the activity of HDAC, one of the histone modifications that plays a role in epigenesis. VPA initiated by hyper-acetylation of histone DNA, which is demonstrated by decreased RNA, RNA/DNA ratio, and insulin in rats whose mothers were given VPA at 10, 13, and 16 days of pregnancies, results in increased glucose levels, supported by microscopic observations using immunohistochemical staining showing low immunoreactivities of insulin of pancreatic beta cells of experimental offspring rats born to experimental pregnant rats.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The graduate study of the first author and the research grand were provided by the Universitas Trisakti to the first author.

Abbreviations

- VPA

Valproate acid

- HDAC

Histone deacetylase

- HAT

Acetyl transferase

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- PGF2α

Prostaglandin F2α

- NBF

Neutral buffered formalin

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- MDM2

Mouse double minute 2 homolog

- ATM/ATR

Serine/threonine-specific protein kinase

- CDK

Cyclin-dependent kinase.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yong J, Ansari PI, Kaufman RJ. When less is better: ER stress and beta cell proliferation. Dev Cell. 2016;36:4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguirre AML, Aguirre AAC, Camberos EP, Solis HE, Martínez NED. Development of the endocrine pancreas and novel strategies for b-cell mass restoration and diabetes therapy. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2015;48:765–776. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20154363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerace D, Wilks MR, O’Brien BA, Simpson AM. The use of β-cell transcription factors in engineering artificial β cells from non-pancreatic tissue. Gene Ther. 2015;22:1–8. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagliuca FW, Millman JR, Gurtler M, Segel M, Dervort AD, Ryu JH, Peterson QP, Greiner D, Melton DA. Generation of functional human pancreatic β cells in vitro. J Cell. 2014;159:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baynest HW. Classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Metab. 2015;6:541. doi: 10.4172/2155-6156.1000541. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henquin JC, Rahier J. Pancreatic alpha cell mass in European subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1720–1725. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2118-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan FC, Wright C. Pancreas organogenesis: from bud to plexus to gland. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:530–565. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shih HP, Sander WM. Pancreas organogenesis: from lineage determination to morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:81–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Wei X, Pang Q, Yia F. Histone deacetylases and their inhibitors: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications indiabetes mellitus. Acta Pharm Sin. 2012;2:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2012.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sostrup B, Gaarn LW, Nalla A, Billestrup N, Nielsen JN. Co-ordinated regulation of neurogenin-3 expression in the maternal and fetal pancreas during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:1190–1197. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ornoy A, Ergaz Z. Alcohol abuse in pregnant women: Effects on the fetus and newborn, mode of action and maternal treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7:364–379. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.da Costa RFM, Kormann ML, Galina A, Rehen SK. Valproate disturbs morphology and mitochondrial membrane potential in human neural cells. Appl In Vitro Toxicol. 2015;1:254–261. doi: 10.1089/aivt.2015.0016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ximenes JCM, Verde ECL, Mazzacoratti MGN, Viana GSB. Valproic acid, a drug with multiple molecular targets related to its potential neuroprotective action. Neurosci Med. 2012;3:107–123. doi: 10.4236/nm.2012.31016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ververis K, Alison H, Karagiannis TC, Licciardi PV. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIS): multi-targeted anticancer agents. Biologics. 2013;7:47–60. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S29965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halsall JA, Turner BM. Histone deacetylase inhibitors for cancer therapy: an evolutionarily ancient resistance response may explain their limited success. Bioessays. 2016;38:1102–1110. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlan MS. Statistics for medicine and health; descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate. Epidemiology Indonesia; Jakarta, Indonesia: 2014. pp. 110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maksoud HMA, El-Shazly SM, El Saied MH. Effect of antiepileptic drug (valproic acid) on children growth. Gaz Egypt Paediatr Assoc. 2016;64:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.epag.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vajda F, O’Brien T. Valproic acid use in pregnancy and congenital malformations. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1771–1772. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1008255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerrini R. Valproate as a mainstay of therapy for pediatric epilepsy. Paediatr Drugs. 2006;2:113–29. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200608020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Felice A, Ricceri L, Venerosi A, Chiarotti F, Calamandrei G. Multifactorial origin of neurodevelopmental disorders: approaches to understanding complex etiologies. Toxics. 2015;3:89–129. doi: 10.3390/toxics3010089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kokate P, Bang R. Study of congenital malformation in tertiary care centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6:89–93. doi: 10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20164638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang OS, Danielsson KG, Ho PC. Misoprostol: pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wlodarczyk BJ, Palacios AM, Chapa CJ, Zhu H, George TM, Finnell RH. Genetic basis of susceptibility to teratogen induced birth defects. Am J Med Genet. 2011;157:215–226. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berridge MJ. Cell cycle and proliferation. Cell Signalling Biology. 2014:901–943. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertoli C, Skotheim JM, De Bruin RAM. Control of cell cycle transcription during G1 and S phases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:518–528. doi: 10.1038/nrm3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, Foote M, Chen J. Effects of histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid on skeletal myocyte development. Sci Rep. 2014;4:1–4. doi: 10.1038/srep07207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher SJ, Tiffen JC, Hersey P. Histone modifications, modifiers and readers in melanoma resistance to targeted and immune therapy. Cancers. 2015;7:1959–1982. doi: 10.3390/cancers7040870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurihara Y, Suzuki T, Sakaue M, Murayama O, Miyazaki Y, Onuki A. Valproic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, decreases proliferation of and induces pecific neurogenic differentiation of canine adipose tissue-derived stem cells. J Vet Med Sci. 2014;76:15–23. doi: 10.1292/jvms.13-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulpen SHW, Pennings JLA, Piersma AH. Gene expression regulation and pathway analysis after valproic acid and carbamazepine exposure in a human embryonic stem cell-based neurodevelopmental toxicity assay. Toxicol Sci. 2015;146:311–320. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giavini E, Menegola E. Teratogenic activity of HDAC inhibitors. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:1–6. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140205144900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu W, Wang Y, Li Y, Wang L, Xiong X, Su J, Zhang Y. Valproic acid improves the in vitro development competence of bovine somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos. Cell Reprogram. 2012;14:138–145. doi: 10.1089/cell.2011.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajendran P, Kidane AI, Yu TW, Dashwood WM, Bisson WH, Löhr CV, Ho E, Williams DE, Dashwood RH. HDAC turnover, CtIP acetylation and dysregulated DNA damage signaling in colon cancer cells treated with sulforaphane and related dietary isothiocyanates. Epigenetics. 2013;8:612–623. doi: 10.4161/epi.24710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi D, Gu W. Dual roles of MDM2 in the regulation of p53: ubiquitination dependent and ubiquitination independent mechanisms of MDM2 repression of p53 activity. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:240–248. doi: 10.1177/1947601912455199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garner E, Raj K. Protective mechanisms of p53-p21-pRb proteins against DNA damage-induced cell death. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1–6. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.3.5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shkreta L, Chabot B. The RNA splicing response to DNA damage. Biomolecules. 2015;5:2935–2977. doi: 10.3390/biom5042935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foleya CJ, Bradleyc DL, Höök TO. A review and assessment of the potential use of RNA:DNA ratios to assess the condition of entrained fish larvae. Ecol Indic. 2016;60:346–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2015.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reef R, Ball MC, Feller IC, Lovelock CE. Relationships among RNA : DNA ratio, growth and elemental stoichiometry in mangrove trees. Funct Ecol. 2010;24:1064–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01722.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chícharo MA, Chícharo L. RNA:DNA ratio and other nucleic acid derived indices in marine ecology. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:1453–1471. doi: 10.3390/ijms9081453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olivar MP, Diaz MV, Chícharo MA. Tissue effect on RNA:DNA ratios of marine fish larvae. Sci Mar. 2009:171–182. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2009.73s1171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pscherer S, Larbig M, Stritsky B, Pfützner A, Forst T. In type 2 diabetes patients insulin glargine is associated with lower postprandial release of intact proinsulin compared with sulfonylurea treatment. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2012;6:634–640. doi: 10.1177/193229681200600318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.FızeIova M, Cederberg H, Stancakova A, Jauhiainen R, Vangipurapu J, Kuusisto J, Laakso M. Markers of tissue-specific insulin resistance predict the worsening of hyperglycemia, incident type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. PLoS ONE. 2014;10:e109772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ali SF, Padhi R. Optimal blood glucose regulation of diabetic patients using single network adaptive critics. Optimal Control Applications & Methods. 2009;32:196–214. doi: 10.1002/oca.920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cerf ME. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol. 2013;37:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arystarkhova E, Liu YB, Salazar C, Stanojevic V, Clifford RJ, Kaplan JH, Kidder GM, Weadner KJ. Hyperplasia of pancreatic beta cells and improved glucose tolerance in mice deficient in the FXYD2 subunit of Na,K-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7077–7085. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.401190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoon KH, Ko SH, Cho JH, Lee JM, Ahn YB, Song KH, Yoo SJ, Kang ML, Cha BY, Lee KW. Selective β-cell loss and α-cell expansion in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Korea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2300–2308. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng S, Vatamaniuk M, Huang X, Doliba N, Lian M, Frank A, Velidedeoglu E, Desai NM, Koeberlein B, Wolf B, Clyde FB, Ali N, Franz MM, James FM. Structural and functional abnormalities in the islets isolated from type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2004;53:624–632. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Otsuka T, Tsukahara T, Takeda H. Development of the pancreas in medaka, Oryzias latipes, from embryo to adult. Dev Growth Differ. 2015;57:557–569. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz MW, Guyenet SJ, Cirulli V. The hypothalamus and beta-cell connection in the gene-targeting era. Diabetes. 2010;59:2991–2993. doi: 10.2337/db10-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomez DL, O’Driscoll M, Sheets TP, Hruban RH, Oberholzer J, McGarrigle JJ, Shamblott MJ. Neurogenin 3 expressing cells in the human exocrine pancreas have the capacity for endocrine cell fate. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0133862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez AM, Rutter GA, Latreille M. MiRNAs in β-cell development, identity, and disease. Front Genet. 2017;7:226. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]