Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Social support is one of the most effective factors on the diabetic self-care. This study aimed to assess social support and its relationship to self-care in type 2 diabetic patients in Qom, Iran.

STUDY DESIGN:

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 325 diabetics attending the Diabetes Mellitus Association.

METHODS:

Patients who meet inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected using random sampling method. Data were collected by the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, with hemoglobin A1C test. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and independent t-test, analysis of variance, Pearson correlation, and linear regression test, using 0.05 as the critical significance level, provided by SPSS software.

RESULTS:

The mean and standard deviation of self-care and social support scores were 4.31 ± 2.7 and 50.32 ± 11.09, respectively. The mean level of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) of patients was 7.54. There was a significant difference between mean score of self-care behaviors and social support according to gender and marital status (P < 0.05). The regression analysis showed that disease duration was the only variable which had a significant effect on the level of HbA1C (P < 0.001). Pearson correlation coefficient indicated that self-care and social support significantly correlated (r = 0.489, P > 0.001) and also predictive power of social support was 0.28. Self-care was significantly better in diabetics with HbA1C ≤7%. Patients who had higher HbA1C felt less, but not significant, social support.

CONCLUSIONS:

This study indicated the relationship between social support and self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetic patients. Interventions that focus on improving the social support and self-care of diabetic control may be more effective in improving glycemic control.

Keywords: Cross-sectional studies, diabetes mellitus, social support, type 2, self-care

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is considered as one of the most significant health issues in the 21st century, causing hyperglycemia.[1] In addition to imposing high economic burden on the person and society, type 2 diabetes constitutes the sixth leading cause of morbidity and mortality that annually affecting more than 4 million people. Type 2 diabetes reduces life expectancy about 15 years in people diagnosed with the disease, and therefore, it constitutes a serious threat in the world.[2] Recently, because of sedentary lifestyle, type 2 diabetes has remarkable prevalence and affects about 20% of Iranian people.[3]

In diabetes, most of diabetes care is carried out by patients. Despite the positive impact that self-care behaviors have had on controlling chronic diseases such as diabetes, several studies have examined the importance of disease control by patient.[4,5] Self-care is a concept that a patient uses her/his knowledge and skill to act health behaviors. Self-care behaviors include healthy eating plan, physical activity, self-monitoring blood glucose, and taking recommended medication and foot care.[6]

One study showed the benefits of self-care for those with diabetes, including a reduced risk in cardiovascular complications to about 80%.[7] There are well-documented studies demonstrating the relationship between self-care behaviors and control blood glucose.[8,9] Adoption of self-care behaviors continues to be a challenge for diabetics.[6,10] The role of related factors to self-care behaviors, such as knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy in patients with diabetes, has been investigated and confirmed.[11,12] Some studies examined the impact of psychosocial factors such as social support on self-care practices.[13] In this regard, Tang's study shows that perceived social support plays an important role in diabetes-specific quality of life and self-care behaviors.[14] According to Stopford's findings, higher perceived social support is associated with a lower level of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C).[15]

Social support is considered as one of the psychosocial factors for adherence to perform self-care and control chronic diseases.[16] Social support is defined as a psychological sense of belonging, acceptance, and assistance which increases people's ability to cope better with stressful conditions. In fact, social support in diabetes is determined as a vital component of mental health promotion which caused to person feels to belong social networking. On the other hand, perceived social support is more important than other categories of social support such as received social support and social fixation.[17,18]

There is good evidence in the field of social support that indicates types and multiple levels of perceived social support[18] Overall, family members, especially spouse, medical staff, and other key members provide the greatest social support. To our knowledge, the studies addressing social support in type 2 diabetes among Iranian people have been limited and also there are little data. Therefore, this study aimed to assess social support and its relationship to self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetic patients in Qom, Iran.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Qom, Center of Islamic Republic of Iran, from November 2015 to March 2016. This city is bordered by Semnan, Arak, Tehran, and Isfahan provinces in the east, west, north, and south of the country, respectively.

The study population consisted of type 2 diabetics who lived in Qom during 2015. The sample size was calculated with a medium effect size of 0.25, 95% power, and significance level (P) of 0.05. Hence, at least 197 participants were required. This study included a sample of 325 people with type 2 diabetes who were attended in the Diabetes Association in Qom.

To be eligible for inclusion of the study: patients be diagnosed type 2 diabetes for at least 1 year or maximum of 5 years, had to be between 35 and 60 years, have received education for at least grade 1–6, to be willing for the study, and have had routine test page of diabetes in the past 3 months. The exclusion criteria included: diagnosed type 2 diabetes for <1 year or more than 5 years, pregnancy, history of surgery or hospitalization in the past 3 months, having major psychiatric problems which has been approved, aged <35 years or above 60 years, and receiving diabetes education in the past 1 year.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the Diabetes Mellitus Association participants who met the inclusion criteria were given adequate information about purpose of the research and invited to participate in the study. Participation was voluntarily and the patients could withdraw any time and also their personal information would be kept confidential. In doing so, we asked family members and people who accompanied patients to leave the area, and then, participants were asked to complete the questionnaires. The level of A1C was measured by latex aggregation immunoassay applying Determiner HbA1C (Kyowa Medix, Tokyo, Japan), which was found not to be influenced by hemoglobin F and other minor hemoglobin species.[19]

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

Patients completed a demographic questionnaire asking information about their age, gender, level of education, marital status, family income, duration of diabetes, and body mass index.

Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities

The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) is a multidimensional tool to measure diabetes self-care activities. SDSCA questionnaire was developed by Toobert et al. and has adequate internal reliability.[20] The original SDSCA version measures four independent factors: exercise, injection, diet type, and blood-glucose testing, while the new SDSCA version assesses five aspects of the frequency of adherence to each self-care practice: exercise, diet type and blood-glucose testing, foot care, and smoking, over the previous 7 days. SDSCA questionnaire contains 12 questions which are scored based on a Likert scale from 0 to 7; lower score indicates a poorer perceived social support. The previous Iranian studies confirmed its reliability and validity.[21]

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a general tool to measure social support. MSPSS questionnaire was developed by Zimet et al,[22] and also, the previous studies confirmed its reliability and validity.[23,24] MSPSS questionnaire contains 12 questions that are scored based on a Likert scale from 0 to 7; rated on a 7-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating more social support (range = 12–84).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Windows); (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data normality was evaluated using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and was determined to show normal distribution. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the relationship between mean score of social support and the educational level. Linear regression model was performed to assess the association of self-care behavior with gender, perceived social support, and duration of diabetes.

In the further approach, we examined if social support and self-care are related to the glycemic control level. To evaluate this purpose, diabetic patients were divided into three groups by mean HbA1C level as follows: good HbA1C< 6.5% and poor HbA1C≥6.5%. Independent sample t-test was used to determine the statistically difference of social support and self-care scores between the two glycemic control groups. P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Results

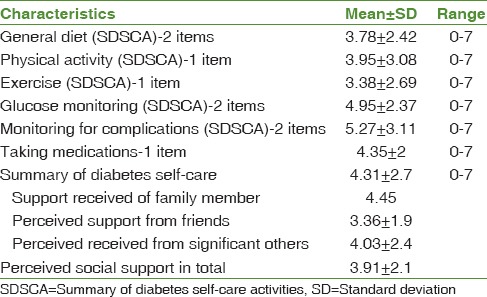

Females were predominant in this study (219 [67.4%] female vs. 106 [%32.6] male). The majority 304 (93.5%) of the participants were married and the rest 21 (%6.5) were single. 15.4%, 27.1%, 28.3, and 29.2 of patients were educated within Grade 1–6, Grade 7–11, diploma, and academic education, respectively. The mean age of patients was 47.96 ± 8.49 years and the mean duration of diabetes was 3.38 ± 1.08 years. The mean and standard deviation of self-care and social support scores were 4.31 ± 2.7 and 3.91 ± 2.1, respectively. Some characteristics related to diabetes care are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Diabetes self-care

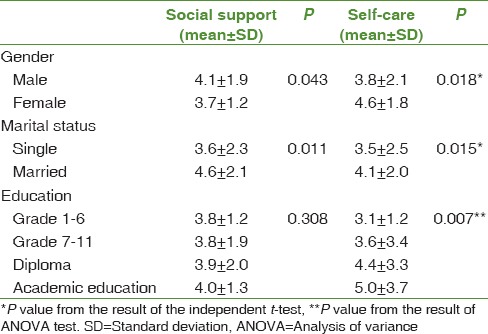

Independent sample t-test also showed that there was a significant difference between mean score of self-care behaviors and social support based on gender and marital status (P ≤ 0.05). According to ANOVA test, no relationship was found between mean score of social support and the educational level (P = 0.308). However, there was a significant relationship between educational level and self-care score (P < 0.001). Specifically, patients with academic education had higher self-care score than other educational levels, and patients who were educated in grade 1–6 significantly had lower self-care score than other educational levels [Table 2].

Table 2.

Social support and self-care based on gender, marital status, and education

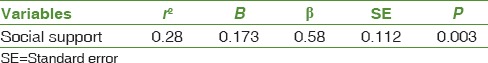

Pearson correlation coefficient indicated that the association between age variable and social support (r = −0.139, P = 0.039) and also history of disease and social support (r = −0.107, P = 0.031) was conversely significant. Furthermore, self-care and age variable had significant inverse association (r = −0.206, P = 0.048); however, there was no significant correlation between duration of diabetes and self-care (r = 0.097, P = 0.059). Self-care and social support significantly correlated (r = 0.489, P = 0.001) and also linear regression was used to predict self-care behavior. Predictive power of social support was 0.28 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Regression analysis between social support and self-care

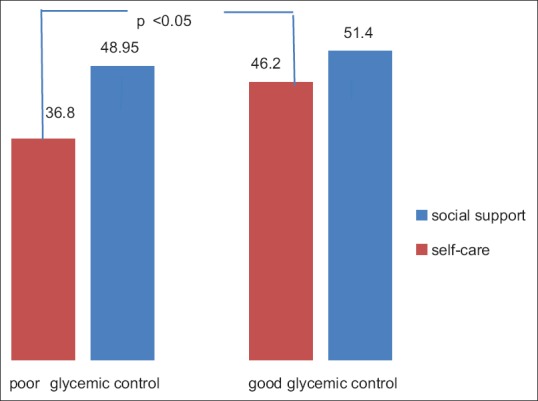

The mean and standard deviation of total self-care and total social support scores in the participants were 4.31 ± 2.7and 3.91 ± 2.1, respectively. Independent sample t-test indicated that there was a statistically significant difference between two good and poor glycemic control groups regarding the self-care scores (P < 0.05). However, these differences were not statistically significant in social support scores [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Difference of social support and self-care scores in two diabetics with poor glycemic control (HbA1 C ≤7%) and good glycemic control (HbA1C >7.0%)

Discussion

This study was conducted to assess relationship between perceived social support and self-care among Iranian with type 2 diabetes. According to our finding, there was statistically significant relationship between perceived social support and self-care among type 2 diabetes patients. This finding indicates that self-care behaviors tend to be followed more frequently among diabetes with greater perceived social support during the life course. In fact, social support, as a psychosocial concept, plays two important roles in type 2 diabetes; (1) improve quality of life and self-care behaviors and (2) enhance patient's adherence with stressful condition.[17,18] Our findings are consistent with the previous studies, including Matsuzawa et al.,[25] who found that social support is a remarkable predictor of self-care and control diabetes. The findings of this study suggest that perceived social support improve motivation and self-care behaviors in type 2 diabetics. This finding is in line with the previous studies.[26,27,28,29]

In this study, perceived social support was close to 60% of the participants and showed at least moderate levels of social support; this finding was in agreement with the previous studies conducted by Mohebi et al.[30] and Shaw et al.[31] Shaw et al. indicated that family members followed by friends provided the greatest social support for patients. Hence, diabetics who received beneficial support from their families and friends prefer to better adherence to self-care behaviors. This result emphasizes the importance of efficient patient–family communication. It is worthy to note that, in Iran, family is the basic unit of social networks where person learns behavioral styles. Accordingly, decision making related to control of disease and medication are also affected by family members.

The highest score of self-care practices was related to taking medication; this finding is similar to the study conducted in Mashad University of Medical Science.[32] It is important note that taking medication is a behavior that comparing other behaviors, including physical activity, healthy diet, and self-monitoring blood glucose, even may perform in the absence of a social support. Furthermore, the lowest score of self-care practices was associated to self-monitoring blood glucose; this finding is in line with Jordan's[6] and Bohanny et al.'s studies.[33]

In addition, the present study indicated that men perceived a greater amount of social support compared with women; this finding is consistent with the previous studies.[6,32,33,34] In the Iranian society, women had a greater responsibility to care for the entire family while women do not equally benefit social support. Actually, social support was higher in married patients because they may have more social networks as well as social interactions with other. Further, marriage may play an encouraging role in practice to self-care behaviors. On the other hand, spouse is considered as the most important source of social support.[35] Further, social support significantly reduced with increasing age and duration of diabetes; this result is similar to study conducted by Skinner et al.[36] The finding in this study was agreement with Mayberry's study that stated there was no association between perceived social support and education level.[37]

Based on our result, there was a significant association between self-care and some demographic variable including gender and marital and education status. Hence, self-care in women was greater than men, and higher self-care was found in married and also persons who had academic education. Although the previous studies[2,29,38] are available to support our result, this finding is conflict with another two studies.[39,40] These differences between the present and these studies probably due to variations in educational programs, knowledge, attitudes, and measurement techniques of self-care lead to difference in self-care within a country and among countries. However, previous studies showed that this relationship differs by gender. For example, Hunt et al. showed that social support was significantly related to diabetes self-management only in men.[41]

Our results showed that the patients with a good self-care behavior had a good achievement in glycemic control levels. The similar results were obtained from Dehghan's et al. study, which confirmed that self-efficacy levels are related to HbA1C in diabetes patients.[42]

Although the social support scores in patient who had a better glycemic control were higher than others, we did not found a significant difference between social support and HbA1C levels. It may be due to the effects of confounding factors. However, some studies demonstrated that good family support significantly affects glycemic control in patient with diabetes type 2.[43] Family support has also been shown to be important in other chronic diseases such as heart failure and hypertension.[44,45] (#68). However, we should consider support from other sources including peers and fellow patients, telephone peer contacts, or Internet-based peer communication, which may improve the outcome of care[46]

Strengths of our study include participation of large patients and those attending in Diabetes Mellitus Association. Our study has some limitations and need to be mentioned. First, the present study was a cross-sectional study; therefore, this study could not infer a causal association between social support and self-care practices. Second, our recruited study patients were a sample of patients already enrolled in diabetes management program and may not be representative of all diabetic patients. Third, the sample size was limited and also many factors might have affected the social support while we did not examine all potential variables related to social support. Finally, we used self-reported questionnaire to collect data. As well as, it is possible that our study be questioned.

Our findings provide useful suggestions for health-care professionals to improve diabetes control and also encourage and create motivation for health-care providers which develop social support. Further research designs could be enhanced by the application of a different format for self-care measures.

Conclusions

The present study indicated the evidence that social support, as an important psychosocial concept, can have a favorable effect on self-care behaviors and glycemic control among type 2 diabetes patients. Hence, it is recommended that families and health-care providers pay more attention to the emotional and supportive needs of patients. It may be useful to conduct a longitudinal study to examine social support on self-care behavior and glycemic control.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We are thankful to the Diabetes Mellitus Association staff of Qom, Iran, for providing a proper setting for patients in the study.

References

- 1.Al-Khawaldeh OA, Al-Hassan MA, Froelicher ES. Self-efficacy, self-management, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2012;26:10–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoenberg NE, Traywick LS, Jacobs-Lawson J, Kart CS. Diabetes self-care among a multiethnic sample of older adults. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2008;23:361–76. doi: 10.1007/s10823-008-9060-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirinzadeh M, Shakerhosseini R. Nutritional value assessment and adequacy of dietary intake in type 2 diabetic patients. IJEM. 2009;11:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helduser JW, Bolin JN, Vuong AM, Moudouni DM, Begaye DS, Huber JC, Jr, et al. Factors associated with successful completion of the chronic disease self-management program by adults with type 2 diabetes. Fam Community Health. 2013;36:147–57. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318282b3d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt KJ, Gebregziabher M, Lynch CP, Echols C, Mauldin PD, Egede LE, et al. Impact of diabetes control on mortality by race in a national cohort of veterans. Ann Epidemiol. 2013;23:74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jordan DN, Jordan JL. Self-care behaviors of Filipino-American adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complications. 2010;24:250–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Povey RC, Clark-Carter D. Diabetes and healthy eating: A systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33:931–59. doi: 10.1177/0145721707308408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asche C, LaFleur J, Conner C. A review of diabetes treatment adherence and the association with clinical and economic outcomes. Clin Ther. 2011;33:74–109. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beard E, Clark M, Hurel S, Cooke D. Do people with diabetes understand their clinical marker of long-term glycemic control (HbA1c levels) and does this predict diabetes self-care behaviours and hbA1c? Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80:227–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vosoghi Karkazloo N, Abootalebi Daryasari G, Farahani B, Mohammadnezhad E, Sajjadi A. The study of self-care agency in patients with diabetes (Ardabil) Mod Care. 2012;8:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohebi S, Azadbakht L, Feizi A, Sharifirad G, Kargar M. Structural role of perceived benefits and barriers to self-care in patients with diabetes. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:37. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.115831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohebi S, Azadbakht L, Feizi A, Sharifirad G, Kargar M. Review the key role of self-efficacy in diabetes care. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:36. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.115827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, Kurlander JE. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: An empowerment-based intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang TS, Brown MB, Funnell MM, Anderson RM. Social support, quality of life, and self-care behaviors among African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34:266–76. doi: 10.1177/0145721708315680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stopford R, Winkley K, Ismail K. Social support and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review of observational studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:549–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rad GS, Bakht LA, Feizi A, Mohebi S. Importance of social support in diabetes care. J Educ Health Promot. 2013;2:62. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.120864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keogh KM, Smith SM, White P, McGilloway S, Kelly A, Gibney J, et al. Psychological family intervention for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:105–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tol A, Baghbanian A, Rahimi A, Shojaeizadeh D, Mohebbi B, Majlessi F. The Relationship between perceived social support from family and diabetes control among patients with diabetes type 1 and type 2. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2011;10:21–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatakeyama I, Maruko T, Ida Y, Tsuruoka A, Maehata E. Fundamental and clinical evaluation for glycosylated hemoglobin measurement kit “Determiner HbA 1C” using latex aggregation immunoassay. Igaku Yakugaku. 1999;41:1181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diab Care. 2000;23:943–50. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pourisharif H, Babapour J, Zamani R, Besharat MA, Mehryar AH, Rajab A. The effectiveness of motivational interviewing in improving health outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;5:1580–4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Besharat M. Unpublished Research Report Tehran University; 2003. Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure of the Multidimensional Scale Perceived Social Support. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meunier J, Dorchy H, Luminet O. Does family cohesiveness and parental alexithymia predict glycaemic control in children and adolescents with diabetes? Diab Metab. 2008;34:473–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuzawa T, Sakurai T, Kuranaga M, Endo H, Yokono K. Predictive factors for hospitalized and institutionalized care-giving of the aged patients with diabetes mellitus in Japan. Kobe J Med Sci. 2011;56:173–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baquedano IR, dos Santos MA, Teixeira CR, Martins TA, Zanetti ML. Factors related to self-care in diabetes mellitus patients attended at Emergency Service in Mexico. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2010;44:1017–23. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342010000400023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao J, Wang J, Zheng P, Haardörfer R, Kegler MC, Zhu Y, et al. Effects of self-care, self-efficacy, social support on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noroozi A, Tahmasebi R, Rekabpour SJ. Effective social support resources in self-management of diabetic patients in Bushehr (2011-12) ISMJ. 2013;16:250–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parham M, Rasooli A, Safaeipuor R, Mohebi S. Assessment of effects of self-caring on diabetics patients Qom diabites association 2013. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2014;21:473–84. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohebi S, Azadbakht L, Feyzi A, Sharifirad G, Hozuri M, Sherbafchi M. Relationship of perceived social support with receiving macronutrients in women with metabolic syndrome; A cross sectional study using path analysis study. 2013;15:121–31. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw BA, Gallant MP, Riley-Jacome M, Spokane LS. Assessing sources of support for diabetes self-care in urban and rural underserved communities. J Community Health. 2006;31:393–412. doi: 10.1007/s10900-006-9018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saedinejat S, Chahipour M, Esmaeily HV, Ghonche H, Fathalizadeh S, Omidbakhsh R. Role of family support in self care of Type II diabetic patients. IJEM. 2014;16:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohanny W, Wu SF, Liu CY, Yeh SH, Tsay SL, Wang TJ, et al. Health literacy, self-efficacy, and self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2013;25:495–502. doi: 10.1111/1745-7599.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong M, Gucciardi E, Li L, Grace SL. Gender and nutrition management in type 2 diabetes. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2005;66:215–20. doi: 10.3148/66.4.2005.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohebi S AL, Feyzi A, Hozoori M, Sharifirad G. Effect of social support from husband on the control of risk factors for metabolic syndrome. IJEM. 2014;16:11–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skinner TC, John M, Hampson SE. Social support and personal models of diabetes as predictors of self-care and well-being: A longitudinal study of adolescents with diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:257–67. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.4.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayberry LS, Osborn CY. Family support, medication adherence, and glycemic control among adults with type 2 diabetes. Diab Care. 2012;35:1239–45. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nouhjah S. Self-care behaviors and related factors in women with type 2 diabetes. Iran J Endocrinol Metabol. 2015;16:393–401. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adwan MA, Najjar YW. The relationship between demographic variables and diabetes self-management in diabetic patients in Amman city/Jordan. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:213–20. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang CC, Tsan KW, Ma SM, Chow SF, Wu CC. The relationship between fasting glucose and HbA1c among customers of health examination services. Formos J Endocrin Metab. 2010;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunt CW, Wilder B, Steele MM, Grant JS, Pryor ER, Moneyham L. Relationships among self-efficacy, social support, social problem solving, and self-management in a rural sample living with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Research and theory for nursing practice. 2012;26(2):126–41. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.26.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dehghan H, Charkazi A, Kouchaki GM, Zadeh BP, Dehghan BA, Matlabi M, et al. General self-efficacy and diabetes management self-efficacy of diabetic patients referred to diabetes clinic of Aq Qala, North of Iran. J Diab Metab Disord. 2017;16:8. doi: 10.1186/s40200-016-0285-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Epple C, Wright AL, Joish VN, Bauer M. The role of active family nutritional support in navajos’ type 2 diabetes metabolic control. Diab Care. 2003;26:2829–34. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.10.2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rajati F, Mostafavi F, Sharifirad G, Sadeghi M, Tavakol K, Feizi A, et al. Atheory-based exercise intervention in patients with heart failure: A protocol for randomized, controlled trial. J Res Med Sci. 2013;18:659–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasandokht T, Farajzadegan Z, Siadat ZD, Paknahad Z, Rajati F. Lifestyle interventions for hypertension treatment among Iranian women in primary health-care settings: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of research in medical sciences: the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. 2015;20(1):54–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Dam HA, van der Horst FG, Knoops L, Ryckman RM, Crebolder HF, van den Borne BH. Social support in diabetes: a systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient education and counseling. 2005;59(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]