Abstract

Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall (GIRR) is a phenomenon wherein the administration of gemcitabine induces an inflammatory reaction within an area of prior radiation. We present the case of a 39-year-old female patient with metastatic breast cancer who experienced GIRR myositis 3 months following postoperative radiotherapy, with additional potential paraspinal myositis following ablative radiotherapy to the thoracic spine. A review of previously published cases of GIRR myositis was performed. The case and literature review describe the clinical course and presentation of GIRR, and highlight the importance of including radiation recall as part of a differential diagnosis when a patient undergoing chemotherapy experiences an inflammatory reaction at a prior site of radiation.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Gemcitabine, Radiation, Bone metastasis

Introduction

Radiation recall describes a well-known, but poorly understood phenomenon by which administration of chemotherapy or another systemic agent induces an inflammatory reaction within a previously irradiated field [1]. Radiation recall was first described in 1959, when it was found that latent effects of radiation, such as dermatitis, could be induced by actinomycin D [2]. Though clinically rare, since that time radiation recall has been observed for various other systemic agents and inciting factors [3]. While the recall phenomenon is most commonly reported as dermatitis, it has also been observed in other organs including the lung, intestine, and muscles [1, 4, 5, 6]. Gemcitabine has previously been implicated in radiation recall. When reported, it is noted to preferentially affect internal tissue and organs [7]. Herein we report a case of a 39-year-old woman with myositis that is clinically consistent with gemcitabine-induced radiation recall (GIRR) myositis. We also review reported cases of GIRR myositis and discuss the findings and implications.

Case Description

Events are outlined in the timeline (Fig. 1) and summarized below. In 2008, the 39-year-old patient was diagnosed with metastatic ER-negative, PR-negative, HER2-positive cancer. At initial presentation, PET scan demonstrated both regional lymph node involvement and osseous metastases. She was started on systemic therapy with Adriamycin and Cytoxan, followed by Taxol and Herceptin. Subsequent therapies included maintenance single-agent Herceptin, followed by Herceptin and lapatinib. By late 2011, her osseous disease showed complete radiologic response on PET scan, and she was offered local therapy to the primary tumor. In January 2012, she underwent a right mastectomy, with ypT2N1a disease, followed by postmastectomy radiation up to 50 Gy with a 10-Gy chest wall boost.

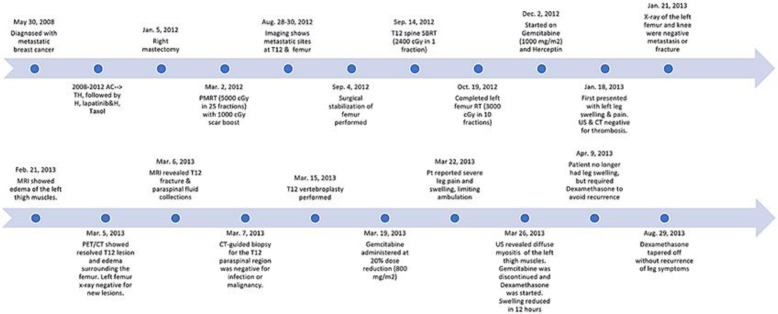

Fig. 1.

Timeline of the case.

In late August 2012, she presented with a painful osseous lesion at the T12 vertebra and an impending pathologic fracture of the left distal femur. She underwent surgical stabilization of the femur with rod placement, followed by postoperative radiotherapy, 30 Gy in 10 fractions (Fig. 2a). T12 was treated with single-fraction stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) up to 24 Gy.

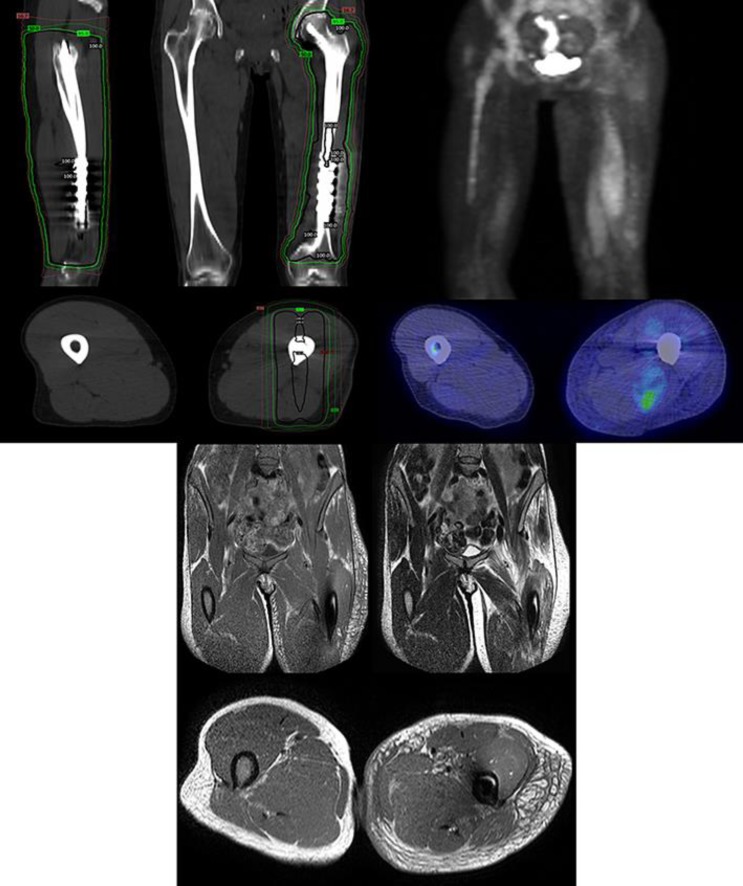

Fig. 2.

Top left: radiation fields of the left femur, with sagittal (top left), coronal (top right), and axial (bottom) views. The isodose levels shown are 16.7, 50, 95, and 100%. Top right: PET/CT showing edema and increased FDG uptake of the left thigh, consistent with myositis, with front-facing 3D (top) and axial (bottom) views. Bottom: MRI showing edema of the left thigh, consistent with myositis, with T1-weighted coronal images (top left), T2-weighted coronal images (top right), and T1-weighted axial images (bottom).

In December 2012, gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2, days 1 and 8) and Herceptin were given in a 21-day cycle. In January 2013, she presented to the Emergency Department with leg swelling, shortness of breath, and pleuritic chest pain to the lower thorax. Physical examination noted left leg swelling and some mild effusion of the left knee. The ultrasound was negative for deep vein thrombosis (DVT), and the chest CT was negative for pulmonary embolism. Symptoms were attributed to a viral syndrome with associated pleurisy.

The patient's symptoms had worsened at the time of her reexamination by oncology on March 2013. PET scan showed increased FDG activity and edema in the left thigh that was thought to be consistent with postradiation inflammatory changes (Fig. 2b). MRI of the thoracic spine demonstrated paraspinal muscle fluid collections and a new T12 fracture, and chemotherapy was held. CT-guided biopsy of the paraspinal fluid collection was negative for abscess or malignancy. Although a T12 vertebroplasty improved the chest/back pain and her swelling, her leg pain persisted.

On March 19, 2013, gemcitabine and Herceptin were resumed with a 20% gemcitabine dose reduction. Within 2 days, she developed worsening leg pain and swelling, and required the use of a cane for ambulation. Repeat extremity ultrasound showed no evidence of DVT, but revealed marked, diffuse enlargement of the vastus medialis or rectus femoris muscles of the left thigh, suggestive of myositis. At that time, her providers noted that her symptoms appeared and worsened following each gemcitabine administration, but improved off chemotherapy. Given the temporal relationship and other negative evaluation, the patient's symptoms were attributed to GIRR from the prior palliative radiotherapy to the left femur. Gemcitabine was stopped, and she was started on dexamethasone and physical therapy. The patient required dexamethasone for relief of her symptoms until August 2013. After a slow taper, she regained leg function and was not rechallenged with gemcitabine.

Over the subsequent 3 years, she had received treatment with Herceptin, ado-trastuzumab, and eribulin/Herceptin without recurrence of the symptoms. Gait was described as normal at the most recent follow-up, and she was described as physically active, engaging in regular exercise. In retrospect, it is also possible that the exacerbation of pain and fluid collection within the paraspinal muscles of T12 seen in March of 2013 may have been related to recall myositis in that region.

Literature Review

A literature search was performed using the search terms “gemcitabine,” “radiation,” “recall,” and “myositis” to compile known reports of GIRR myositis (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3). Twenty-one cases were identified as having myositis in a radiation port following gemcitabine treatment. Fractionated radiation doses ranged from 28 to 70.2 Gy.

Table 1.

Collection of previous case reports of gemcitabine-induced radiation recall myositis

| Author | Cancer type | Radiation location | Dose | CTx regimen | Time between RT and gemcitabine start | Time between RT completion and recall symptoms | Clinical symptoms/signs | Under-going chemo at time of symptom onset? | Imaging findings (and modality) | Treatment | Outcome | Post-treatment CTx? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alco et al. [19] | Pancreatic adeno carcinoma | Pancreas and regional lymph nodes | 1.8 Gy × 25 (45 Gy) | Gemcitabine 1,250 mg/m2/week, 3 weeks in 4 week cycle | 0 (concurrent) | 20 weeks | Tender mass, pain, and swelling of abdominal muscles | No (last dose 1 month before onset) | Edema and inflammation of the anterior and right abdominal wall muscles (MRI) | Corticosteroids, NSAIDs, and gabapentin | Symptom reduction in 1 week; clinical and radiologic findings resolved in 1 month | N/A |

| Alco et al. [19] | NSCLC | Left upper lobe and ipsilateral L2 lymph nodes | 62 Gy total (fractions N/A) | Gemcitabine (1,200 m/m2 for 1–8 days), and carboplatin (AUC 5.5 for days 1 and 30), for 3 cycles; gemcitabine reduced to 800 mg/m2 after first cycle because of intolerance | N/A (CTx started after RT) | N/A (∼104 days after starting CTx) | Pain and swelling of left breast and chest wall, with reduced ROM of arm and shoulder | No (last dose 2 weeks before onset) | Edema and soft tissue reaction at the left breast musculature and subcutaneous soft tissue (MRI) | Corticosteroids, NSAIDs, opioids, antihistamines, SOD, pentoxifylline, vitamin E, gabapentin, topical lidocaine and selenium | Meds did not affect myositis; pain reduced after 4 months, resolved after 9 months, with lasting reduced ROM | N/A |

| Delavan et al. [15] | Breast cancer | Left thigh | 8 Gy × 1 (8 Gy) (4 years prior) 3 Gy × 13 (39 Gy) (4 months prior) |

Gemcitabine (unknown dosage) | 17 days | 107 days | Increasing pain and swelling to the posterior left thigh, warm to palpation | No (last dose ∼3.5 weeks before onset) | Increased signal intensity in the posterior thigh musculature (MRI) | Dexamethasone | Symptoms improved over 3 days, symptom free 1 week later | Not reported |

| Eckardt et al. [17] | Synovial sarcoma | Right forearm | 3.5 Gy × 8 (28 Gy) preop, followed by 2 Gy × 10 (20 Gy) boost | Gemcitabine (900 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8) and docetaxel (100 mg/m2 on day 8) for 2 cycles at 21 and 28 days, respectively | 5 days | 40 days | Swelling of the right forearm with progressively worsening range of motion, compartment syndrome | No (last dose 7 days before onset) | Edema of the flexor compartment muscles, with layering fluid along the superficial fascia and between the muscles (MRI) | Dexamethasone | Patient required slow taper corticosteroids for multiple months; patient continues to have muscle edema and myositis on 1-year follow-up MRI. | No |

| Fakih [20] | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Pancreas | 1.8 Gy × 28 (50.4 Gy) | Concurrent fluorouracil (2,000 mg/m2/day for 5 days a week) and gemcitabine (200 mg/m2 weekly) followed by adjuvant gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2/week for 3 weeks every 4-week cycle) | 0 days (concurrent) ∼21 days to initiation of adjuvant dose gemcitabine |

∼18 weeks | Erythematosus rash overlying a tender mass in the epigastrium | Yes | Enlarged left and right rectus abdominus with areas of heterogeneity (CT) | None, other than withholding gemcitabine | Complete resolution | Yes (capecitabine, docetaxel, and cisplatin) |

| Fogarty et al. [21] | NSCLC | Lung | 3 Gy × 12 (36 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8) and carboplatin (AUC 5, day 1) | ∼3 months | ∼4.5 months | Posterior chest wall pain with localized tenderness, skin rash, elevated CK, ESR | Yes | Enhancement of the chest wall musculature consistent with nonspecific inflammatory change (MRI) | NSAIDS, oral steroids | Symptoms improved but persistent minor skin changes and subcutaneous fibrosis | Not reported |

Table 2.

Collection of previous case reports of gemcitabine-induced radiation recall myositis (continued)

| Author | Cancer type | Radiation location | Dose | CTx regimen | Time between RT and gemcitabine start | Time between RT completion and recall symptoms | Clinical symptoms/signs | Undergoing chemo at time of symptom onset? | Imaging findings (and modality) | Treatment | Outcome | Post-treatment CTx? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Friedlander et al. [7] | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Pancreas and regional lymph nodes | 1.8 Gy × 28 (50.4 Gy) | Gemcitabine (40 mg/m2 biweekly and concurrently with radiation, followed by 1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 3 weeks per month) | 39 days | 3 months | Tenderness of rectus muscles, mild rash, elevated CK | Yes | Increased signal in the subcutaneous tissue of the anterior abdominal wall (MRI) | Corticosteroids | Complete resolution, no recurrence after steroid tapering | Not reported |

| Ganem et al. [22] | Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung | Pelvis | 3 Gy × 11 (33 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, 15) and cisplatin (100 mg/m2 on day 15) | 1.5 months | 5 months | Right buttock pain | Yes | Hypersignal and edema on gluteal soft tissue (MRI) | Oral opiates, antibiotics, steroids | Alleviation over the course of 3 months | Not reported |

| Graf et al. [16] | NSCLC and anal cancer, history of dermatomyositis | Pelvis | Not reported | 5-FU and MMC given with pelvic RT for anal cancer, carboplatin and gemcitabine (dosage not given) | 2 months | 4 months | Erythema, swelling, warmth, and tenderness of the buttocks and groin area | Yes | High signal in the bilateral gluteal maximus, quadratus femoris, adductor magnus, obturator externus and right iliopsoas muscles (MRI), elevated CK | Prednisone and opiate analgesia | Gradual improvement with steroids | Not reported |

| Grover et al. [5] | Adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine neoplasm, unknown primary | Left hip and left acromion | 3 Gy × 10 (30 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,250 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC 5) | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | Worsening pain in left shoulder and hip | Yes | Soft tissue edema of the muscles adjacent to the left acromion and the left hip (MRI) | Narcotics | Pain resolved 5 months after radiotherapy | Gemcitabine therapy continued |

| Horan et al. [23] | NSCLC | Lung | 3 Gy × 8 (24 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2, weekly) | 2 months | ∼13 weeks | Pain and swelling of the right pectoralis major, biopsy proven muscle necrosis | Yes | Thickening of right pectoralis major muscle (CT) | Analgesics | Symptoms gradually declined when gemcitabine was stopped | Gemcitabine re-challenge, no further symptoms |

| Jeter et al. [11] | Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | Pancreas | 1.8 Gy × 28 (50.4 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 one dose; followed by 750 mg/m2 weekly for 9 months) | 3 weeks | 3 months | Abdominal wall tenderness and erythema | Yes | Subcutaneous fat stranding and decreased density of rectus muscles in radiation portal (CT) | Ibuprofen | Symptoms responsive to ibuprofen | Gemcitabine re-challenge, no further symptoms |

| Lock et al. [24] | Hepatic adenocarcinoma | Liver | 2.94 Gy × 15 (44.1 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 for days 1 and 8 for a 3-week cycle) | 8 weeks | 18 weeks | Abdominal discomfort with induration; overlying skin erythema | Yes | Enhancement of abdominal muscles with thickening (MRI) | Ibuprofen, vitamin E, and vitamin C | Gradual resolution over the course of 6 weeks | Gemcitabine was continued, reduction of symptoms |

| Miura et al. [25]a | NSCLC | Right hip | 2 Gy × 25 (50 Gy) | Concurrent cisplatin (80 mg/m2 day 1) and vinorelbine (20 mg/m2, days 1, 8, and 15) followed by gemcitabine (800 mg/m2 biweekly) | 1 month | 3 months | Right thigh pain | N/A | Edema within right thigh muscles (MRI) | Analgesics | Gradual resolution of symptoms | Yes (unknown regimen) |

Table 3.

Collection of previous case reports of gemcitabine-induced radiation recall myositis (continued)

| Author | Cancer type | Radiation location | Dose | CTx regimen | Time between RT and gemcitabine start | Time between RT completion and recall symptoms | Clinical symptoms/signs | Undergoing chemo at time of symptom onset? | Imaging findings (and modality) | Treatment | Outcome | Post-treatment CTx? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miura et al. [25]a | NSCLC | Lung | 2 Gy × 30 (60 Gy) | Concurrent cisplatin and (80 mg/m2 day 1) and vinorelbine (20 mg/m2, days 1 and 8) followed by vinorelbine (13 mg/m2 biweekly) and gemcitabine (800 mg/m2 biweekly) | 3 months | 5.5 months | Upper chest muscle pain | N/A | Enhancement of pectoralis muscles (MRI) | NSAIDs | Improvement of symptoms | Yes (gefitinib) |

| O'Regan et al. [10] | Hodgkin lymphoma | Chest | 1.8 Gy × 22 (39.6 Gy) | 4 cycles of gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin (unknown dosage) | 2 months | 5 months | Worsening bilateral anterior chest pain, pectoralis muscle necrosis by biopsy | No (last dose 2.5 weeks before presentation) | Diffuse bilateral swelling of the pectoral muscles with mild stranding of the adjacent subcutaneous fat (CT) | Analgesics | Complete resolution | Not reported |

| Patel et al. [26] | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | Head and neck | 70.2 Gy total (fractions N/A) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) and oxaliplatin (100 mg/m2) every 2 weeks | N/A (CTx started after RT) | 6 months | Bilateral neck pain and swelling with restriction of neck movement | Yes | Diffuse bilateral soft-tissue edema of the muscles in the cervical neck (MRI) | Dexamethasone | Symptoms worsened with tapering of dexamethasone/low-dose prednisone started without recurrence. | Not reported |

| Pinson et al. [27]b | NSCLC | Lung | 3 Gy × 10 (30 Gy) | Carboplatin (AUC 5 on day 1) and gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8), 3-week cycle | 4 weeks | 14 weeks | Skin erythema, upper chest muscle pain | Yes | Swelling of the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor (CT) | Ibuprofen | Complete resolution in 3 weeks | Not reported |

| Squire et al. [14] | NSCLC | Pelvis (left sacroiliac and left acetabulum) | 3 Gy × 10 (30 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) | 1 month | 3 months | Tenderness and discomfort to left hip and buttock, elevated CK | Yes | Edema in gluteal muscles (MRI) | Oral prednisone | Symptoms worsened with tapering of prednisone and improved with increasing doses | Gemcitabine continued for 5 more months, symptoms controlled with prednisone |

| Welsh et al. [28] | Bladder cancer | Para-sacral region | 2.5 Gy × 18 (45 Gy) | Gemcitabine and cisplatin (unknown dosage) | 4 weeks | 5 months | Pain in bilateral superolateral gluteal regions | Yes | Band-like pattern of edema on gluteal region (MRI) | NSAIDs, prednisone | Complete resolution after 6 weeks, but with visible residual scar and muscular atrophy | CTx continued |

| Current | Breast cancer | Left thigh (femur)/T12 vertebra | 3 Gy × 10 (30 Gy)/24 Gy × 1 (24 Gy) | Gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 for days 1 and 8) and herceptin (342 mg every 3 weeks) | 54 days/79 days | 3 months/5.7 months | Worsening leg pain and swelling/Chest and back pain | Yes | Enlargement of muscles of the left thigh (US)/ T12 fracture and paraspinal fluid collections (MRI) | Dexamethasone/T12 vertebroplasty | Progressive resolution of symptoms after 4-month course of dexamethasone/Reduction of chest and back pain following vertebroplasty | Yes (herceptin) |

Paper is written in Japanese.

Paper is written in Dutch.

The time interval between radiation and chemotherapy initiation ranged from 0 days to 4 months. The majority had chemotherapy more than 1 month after radiotherapy. The time between radiation and onset of recall symptoms varied from 4 weeks to 5.5 months. Only 1 patient had symptoms less than 1 month after radiation, 20 were ≥3 months, 10 were ≥4 months, and 7 were ≥5 months. All patients achieved at least partial improvement of their symptoms with discontinuation of gemcitabine, regardless of whether their treatment consisted of steroids (9 patients), NSAIDs (5 patients), analgesics (4 patients), or no treatment at all (2 patients). Out of the 9 confirmed patients who resumed chemotherapy following myositis, 5 patients underwent gemcitabine rechallenge, with only 1 patient requiring concomitant steroids for symptom control.

The patient described in the present report is consistent with other reported cases. The time intervals between chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and the onset of symptoms are within the range of the other cases. The current case of possible myositis at T12 was the only case associated with a single fraction of ablative radiotherapy. Interestingly, our patient had prior chest wall radiotherapy, but did not develop evidence of recall in that location. In review of the literature, this is consistent with other cases in which recall myositis did not appear in all prior sites of radiotherapy. Remote courses were less often affected by recall myositis. These findings are also consistent with prior reviews of radiation recall that suggest a possible relationship between the time interval from radiation to chemotherapy and the severity of recall symptoms [1, 3, 8]. However, such a correlation likely depends on the relationship between several factors, such as drug type, dosage, radiation location, radiation dosage, and timing of each treatment [3].

Discussion

Radiation recall is a delayed inflammatory response at a site of prior radiation [9, 10]. GIRR has been noted to have a predilection for soft tissue and internal organs, resulting in a less typical appearance of radiation recall. For example, GIRR has been documented to cause pseudocellulitis, acute ascending colitis, abdominal wall and subcutaneous fat stranding, optic neuritis, lymphangitis, rectal hemorrhage, brainstem radionecrosis, and myositis [5, 9, 11, 12, 13]. These atypical presentations highlight the importance of clinical awareness of GIRR.

The diagnosis of GIRR myositis is challenging, as it may appear similar to infection, thrombosis, or other sources of inflammation [14]. A few key signs may help distinguish this condition. Primarily, the inflammation is confined to a prior radiation portal. Furthermore, there is a temporal relationship between the timing of gemcitabine administration and appearance of symptoms [9]. Radiologic studies may be used to support the diagnosis of myositis with appearance of swelling and edema of the underlying musculature. They may also assist in ruling out other potential etiologies [15]. Because reported cases of myositis have been associated with elevated creatinine kinase and even compartment syndrome, appropriate recognition and treatment is essential to facilitate recovery and minimize morbidity [10, 16, 17]. Review of cases suggests that the most important factor for resolution is the discontinuation of gemcitabine, with the potential use of anti-inflammatory medications.

The mechanisms of action of radiation recall remain poorly understood. However, the varied presentations of GIRR, even within an individual's prior sites of radiotherapy, suggest that multiple factors influence both the appearance and severity of recall. Jeter et al. [11] proposed that the doses of gemcitabine of 600 mg/m2 or higher may pose a higher recall risk. Others suggest that higher radiation treatment doses or shorter intervals between radiotherapy and chemotherapy may influence recall development [9]. However, these are not well-defined risk factors. With an increased use of gemcitabine across many tumor types, along with routine use of definitive and palliative radiotherapy, clinicians should be alerted to this possible complication.

We suspect that the exacerbation of pain at the site of T12 SBRT along with the MRI and biopsy findings are consistent with a focal recall myositis at that location. Our patient did not have further exacerbation of pain at that site with the dose-reduced gemcitabine. This suggests that the intervention with vertebroplasty may have affected the local environment. The underlying recall mechanism may also have differed from that in the leg. Radiation recall at an SBRT-treated site had been reported in the past, although the recall effect was induced by sorafenib and manifested itself in the form of dermatitis [18].

Due to its rare and unpredictable onset, radiation recall continues to be a poorly understood phenomenon. This is further complicated by the possibility that there are multiple mechanisms for different medications (gemcitabine, carboplatin, etc.) and/or types of recall (dermatitis, myositis, etc.). Current hypotheses for explaining radiation recall include sensitivity of descendants of cells that survive radiation, changes in local vasculature, and drug-induced hypersensitivity reactions [1]. There is not enough evidence to support any definite mechanism [1, 9]. However, the drug-induced hypersensitivity hypothesis appears to best explain the characteristics of radiation recall. This hypothesis describes radiation recall as a nonimmune inflammatory reaction triggered by certain drugs at a site where the inflammatory threshold has been lowered by radiation. Prior radiation to a specific site may induce constant low-level expression of several inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, PGDF-β, TNF-α, and TGF- β [18]. Introduction of drugs such as gemcitabine may then lead to upregulation of such inflammatory cytokines inducing the recall reaction [1]. This theory is further supported by the various clinical presentations of radiation recall, including the timing of onset, the lack of worsening reactions following rechallenge in some cases, and the induction of recall from noncytotoxic agents (such as simvastatin) [1, 8].

Conclusion

In conclusion, GIRR myositis is a rare, but significant reaction that may present like other conditions such as DVT or infection. As such, it should be part of the differential diagnosis when a patient on gemcitabine reports pain and swelling to a previously irradiated area, although other causes should be thoroughly investigated. In particular, GIRR myositis should be considered when there is a shorter time interval between the completion of radiation and the initiation of chemotherapy. Discontinuation of chemotherapy and possibly the use of anti-inflammatory medications are important steps to reduce symptoms and improve the patient's quality of life. In some cases, patients have been successfully rechallenged with gemcitabine, although that may not always be possible.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose. IRB approval was obtained.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Azria D, Magné N, Zouhair A, Castadot P, Culine S, Ychou M, et al. Radiation recall a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005 Nov;31((7)):555–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Angio GJ, Farber S, Maddock CL. Potentiation of x-ray effects by actinomycin D. Radiology. 1959 Aug;73((2)):175–7. doi: 10.1148/73.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burris HA, 3rd, Hurtig J. Radiation recall with anticancer agents. Oncologist. 2010;15((11)):1227–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kundak I, Oztop I, Soyturk M, Ozcan MA, Yilmaz U, Meydan N, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin induced radiation recall colitis. Tumori. 2004 Mar–Apr;90((2)):256–8. doi: 10.1177/030089160409000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grover S, Jones JA, Teitelbaum U, Apisarnthanarax S. Radiation recall myositis two sites, one patient. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015 Jan–Feb;5((1)):39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schweitzer VG, Juillard GJ, Bajada CL, Parker RG. Radiation recall dermatitis and pneumonitis in a patient treated with paclitaxel. Cancer. 1995 Sep;76((6)):1069–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950915)76:6<1069::aid-cncr2820760623>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedlander PA, Bansal R, Schwartz L, Wagman R, Posner J, Kemeny N. Gemcitabine-related radiation recall preferentially involves internal tissue and organs. Cancer. 2004 May;100((9)):1793–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camidge R, Price A. Characterizing the phenomenon of radiation recall dermatitis. Radiother Oncol. 2001 Jun;59((3)):237–45. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burris HA, 3rd, Hurtig J. Radiation recall with anticancer agents. Oncologist. 2010;15((11)):1227–37. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Regan KN, Nishino M, Armand P, Kelly PJ, Hwang DG, Di Salvo D. Sonographic features of pectoralis muscle necrosis secondary to gemcitabine-induced radiation recall case report and review of current literature. J Ultrasound Med. 2010 Oct;29((10)):1499–502. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.10.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeter MD, Jänne PA, Brooks S, Burstein HJ, Wen P, Fuchs CS, et al. Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002 Jun;53((2)):394–400. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02773-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimoto K, Akise Y, Miyazawa M, Kutsuki S, Hashimoto S, Uchida A. A Case of Severe Rectal Hemorrhage Possibly Caused by Radiation Recall after Administration of Gemcitabine. Keio J Med. 2016;65((1)):16–20. doi: 10.2302/kjm.2014-0015-CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan DH, Bunce PE, Liles WC, Gold WL. Gemcitabine-related “pseudocellulitis” report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Sep;45((5)):e72–6. doi: 10.1086/520684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Squire S, Chan M, Feller E, Mega A, Gold R. An unusual case of gemcitabine-induced radiation recall. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006 Dec;29((6)):636. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000182426.43595.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delavan JA, Chino JP, Vinson EN. Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall myositis. Skeletal Radiol. 2015 Mar;44((3)):451–5. doi: 10.1007/s00256-014-1996-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf SW, Limaye VS, Cleland LG. Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall myositis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014 Jul;17((6)):696–7. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckardt MA, Bean A, Selch MT, Federman N. A child with gemcitabine-induced severe radiation recall myositis resulting in a compartment syndrome. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013 Mar;35((2)):156–61. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31827e4c28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh CH, Lin SC, Shueng PW, Kuo DY. Recall radiation dermatitis by sorafenib following stereotactic body radiation therapy. Onco Targets Ther. 2014 Jun;7:1111–4. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S64706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alco G, et al. Gemcitabine induced radiation recall myositis report of two cases. Int J Hematol Oncol. 2009;19((4)):249–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fakih MG. Gemcitabine-induced rectus abdominus radiation recall. JOP. 2006 May;7((3)):306–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fogarty G, Ball D, Rischin D. Radiation recall reaction following gemcitabine. Lung Cancer. 2001 Aug–Sep;33((2–3)):299–302. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(01)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganem G, Solal-Celigny P, Joffroy A, Tassy D, Delpon A, Dupuis O. Radiation myositis the possible role of gemcitabine. Ann Oncol. 2000 Dec;11((12)):1615–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1008353224251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horan G, Smith SL, Podd TJ. Gemcitabine-induced radiation necrosis of the pectoralis major muscle. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2006 Feb;18((1)):85. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lock M, Sinclair K, Welch S, Younus J, Salim M. Radiation recall dermatitis due to gemcitabine does not suggest the need to discontinue chemotherapy. Oncol Lett. 2011 Jan;2((1)):85–90. doi: 10.3892/ol.2010.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miura G, Matsumoto T, Tanaka N, Emoto T, Kawamura T, Matsunaga N. Two cases of radiation myositis probably induced by recall phenomenon. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2003 Sep;63((8)):420–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel SC, et al. Gemcitabine-induced radiation recall myositis in a patient with relapsed nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2017 Jan–Feb;7((1)):e19–e22. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinson PJ, Griep C, Sanders WH, Lelie B. Myositis as a “radiation-recall phenomenon” following palliative chemotherapy with carboplatin-gemcitabin for non-small-cell pulmonary carcinoma. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2006 Aug;150((34)):1891–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welsh JS, Torre TG, DeWeese TL, O'Reilly S. Radiation myositis. Ann Oncol. 1999 Sep;10((9)):1105–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008365221440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]