Abstract

CONTEXT:

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is an important cause of death during the 1st year of life and includes a special group of cardiac diseases that exist from birth. These conditions arise due to the abnormal development of an embryo's normal structures.

AIMS:

A case–control study was conducted to investigate the determinant factors leading to CHD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

All newborns who have been diagnosed with CHD upon echocardiography in 2013 were considered as cases. The number of samples required was randomly selected from the newborns who lacked CHD on cardiography. The mothers of both groups were handed the questionnaires.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS USED:

SPSS 23 was employed to analyze the data.

RESULTS:

A statistically significant association was seen between CHD and a positive family history (FH) (P < 0.001), consanguinity (P < 0.001), maternal diabetes (P = 0.004), the use of antiepileptics during the first 45 days of gestation (P = 0.002), and the mother's education status (P > 0.001). No significant association was observed between CHD in the newborn and the age below 20 and above 35 years and (P = 0.11), maternal body mass index (BMI) (P = 0.44), smoking during the first 45 days of gestation (P = 0.017), and maternal rheumatologic diseases (P = 0.4).

CONCLUSIONS:

Newborns are at a greater risk of having CHD born from mothers with a FH of CHD, from consanguineous marriages, history of diabetes, antiepileptic use, and lack of folic acid use. However, no significant associations were found between newborn CHD and maternal age, BMI, or cigarette smoking.

Keywords: Case–control, congenital heart disease, risk factors affecting congenital heart disease

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is an important cause of death during the 1st year of life and includes a specific group of cardiac diseases that exist from birth. Usually, these conditions arise due to the abnormal development of an embryo's normal structures and/or the cessation of their maturity during the early stages of embryonic development. The leading cause of neonatal death from congenital anomalies is congenital heart defects. A third of deaths resulting from anomalies are related to CHD, encompassing one-tenth of all neonatal deaths). Twenty-five to thirty percent of beds occupied in the pediatric ICU are by children with CHD. Thus, a great portion of healthcare costs is spent on these diseases.[1]

The causes of most CHDs remain unknown. Mostly, they are multifactorial and result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. A small percentage of CHD is related to chromosomal abnormalities, especially trisomies 18, 13, 21 and Turner's Syndrome.[2,3]

The genetic background of CHD incidence among the healthy population is approximately 0.8%. Two to four percent of CHD cases are related to environmental or maternal conditions and teratogenic effects, including, maternal diabetes mellitus, maternal phenylketonuria, maternal lupus, congenital rubella syndrome, and the intake of drugs (lithium, ethanol, warfarin, thalidomide, Vitamin “A” derivatives, sodium valproate, carbamazepine, antimetabolites).[2,3,4]

The number of newborns with CHD in Qom is high, of which there is no precise estimate of them. Moreover, the costs of treating these children and their mortality rates are also high. Hence, the research team attempted to identify the causes of its occurrence, the information with which we can help reduce its risk factors, its patients, and its mental, social and economic burdens on the families and society.

Materials and Methods

A case–control study was conducted in which the case group included newborns with CHD, and the control group included newborns without CHD. The aforementioned all newborns were admitted to Hazrat Masoumeh Hospital's Heart Clinic. Convenience sampling was used to select the controls, and simple random sampling was used to select the cases. Moreover, the two groups were homogenous in terms of age and sex. Based on the following equation, approximately 221 individuals were selected for each group, totaling 442 persons.

Variables under study were CHD, maternal age, family marriage, family history (FH), maternal diabetes, obesity, cigarette smoking, antiepileptic use, folic acid use, maternal rheumatologic diseases, and educational status.

Data were gathered through questionnaires and interviews with the mothers after birth; their medical records were also collected.

The statistical software of SPSS version 23 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was employed to analyze the data. Descriptive analytics such as mean, standard deviation, and frequency of the quantitative and qualitative variables were computed. The Chi-square test was used to examine the association between the variables. Logistic regression was also applied.

Results

The mean maternal age was 28.48 and 28.62 years in the case and control groups, respectively. The mean body mass index (BMI) in the case and control groups was 28.95 and 27.93, respectively.

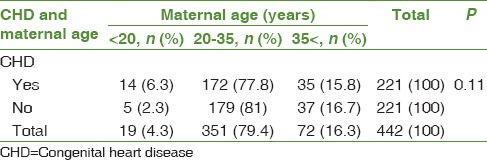

No significant association was observed between <20 and 35< years of maternal age and CHD in the newborn (χ2 = 4.46, P = 0.11) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparing the association between maternal age and congenital heart disease in both groups

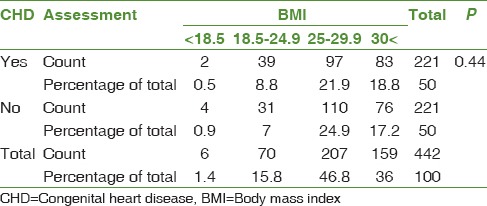

There was no significant association between maternal BMI and birth of a baby with CHD (χ2 = 2.70, P = 0.44) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparing the association between maternal obesity and congenital heart disease in both groups

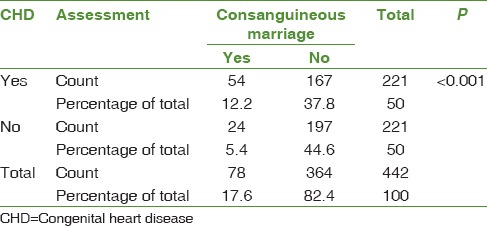

There was a statistically significant association between CHD and consanguineous marriage (χ2 = 14, P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparing the association between consanguineous marriage and congenital heart disease in both groups

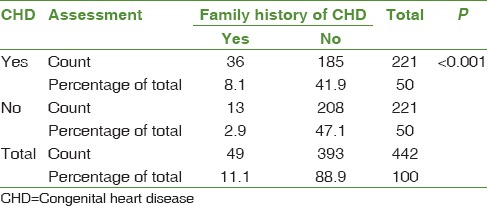

There was a statistically significant association between CHD and a positive FH (χ2 = 12.10, P < 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparing the association between a positive family history and congenital heart disease in both groups

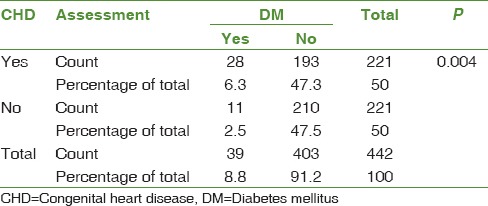

There was a statistically significant association between CHD and maternal diabetes (χ2 = 8.13, P = 0.004) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Comparing the association between maternal diabetes and congenital heart disease in both groups

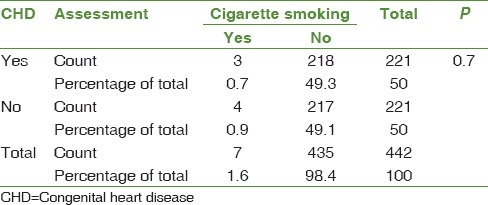

There was no statistically significant association between CHD and cigarette smoking by the mother during the first 45 days of gestation (χ2 = 0.15, P = 0.7) [Table 6].

Table 6.

Comparing the association between cigarette smoking by the mother and congenital heart disease in both groups

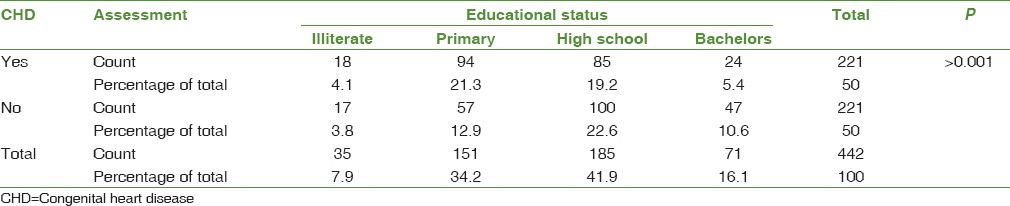

There was a statistically significant association between CHD and the mother's educational status (χ2 = 17.80, P > 0.001) [Table 7].

Table 7.

Comparing the association between the mother's educational status and congenital heart disease in both groups

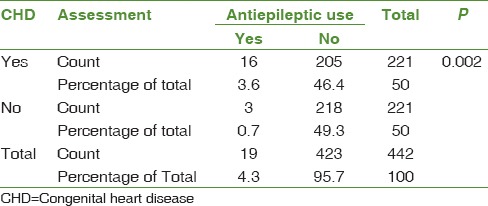

There was a statistically significant association between CHD and antiepileptic use by the mother during the first 45 days of gestation (χ2 = 9.30, P = 0.002) [Table 8].

Table 8.

Comparing the association between antiepileptic use by the mother and congenital heart disease in both groups

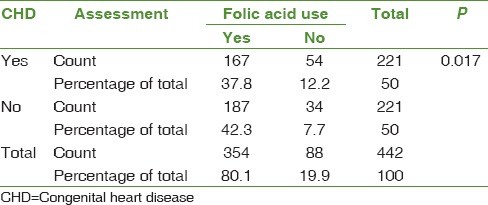

There was a statistically significant association between CHD and the lack of folic acid use by the mother during the first 45 days of gestation (χ2 = 5.70, P = 0.017) [Table 9].

Table 9.

Comparing the association between folic acid used by the mother and congenital heart disease in both groups

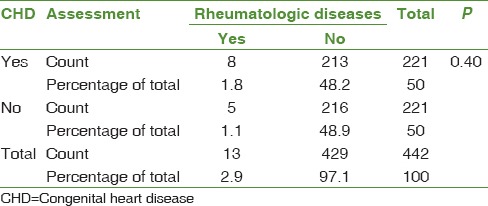

There was no statistically significant association between CHD and maternal rheumatologic diseases (χ2 = 0.71, P = 0.40) [Table 10].

Table 10.

Comparing the association between maternal rheumatologic diseases and congenital heart disease in both groups

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the indices related to CHD in Qom province. In this study, maternal age, maternal education, maternal anticonvulsant therapy, rheumatologic disease, smoking, familial marriage, and familial FH of CHD. In two groups, case and control groups were examined. The case group included newborns with CHD diagnosed in echocardiography, and the control group consisted of newborns without CHD were selected from newborns referring to Hazrat Masoumeh Hospital's Heart Clinic.

This study showed that positive familial history, familial marriage, maternal diabetes, lack of folic acid during pregnancy, use of anticonvulsants, and maternal education with CHD have a significant relationship. On the other hand, the study suggested that there was no significant relationship between maternal age, maternal BMI, smoking in the first 45 days of pregnancy, and maternal rheumatologic abnormalities with cardiac abnormalities in the newborn.

In two studies conducted by Tandon et al. and Ul Haq et al., several indicators of CHD in newborns were examined and found that there is a relationship between familial marriage and a positive FH of CHD with CHD, which is similar to the current study. However, in the study of Tandon et al., contrary to the current study, there was a significant relationship between the incidence of CHD disease with the parental age index during pregnancy.[5,6]

Kuciene and Dulskiene, Øyen et al., and Fung et al. studied the indices related to CHD and like the current study suggested relationship between maternal disease such as diabetes and positive FH with the incidence of the CHD. However, there was a significant relationship between maternal BMI with CHD; this is a different result from our study.[7,8,9]

Roodpeyma et al. studied the risk factors of CHD in the Taleghani Hospital and observed that although CHD was associated with extracardiac anomalies and chromosomal disorders, maternal diseases, drugs used during the first trimester, history of abortion, and stillbirth did not have any proven effects on CHD occurrence, which was completely different from the current study and previous foreign studies.[10]

We had some limitations in this study including parents’ lack of cooperation to participate and using a questionnaire that is not free of errors. This study was conducted for the first time in Qom province to determine the factors affecting CHD.

Conclusions

According to the results of this study and foreign studies conducted that familial marriage, positive family history, maternal diabetes, lack of folic acid, and anticonvulsant drug use during pregnancy are associated with CHD. Moreover, it shows the need for further study with larger volumes in the country to evaluate the risk factors associated with CHD to reduce the economic and social damage.

Limitation

On the other hand, the good feature of this study is the previous study in this regard, the study over the period of 5 years and the higher number of samples in this study than others.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article has been derived from an M. D. thesis of Qom University of Medical Sciences; therefore, we appreciate the hospital personnel's cooperation.

References

- 1.Başpinar O, Karaaslan S, Oran B, Baysal T, Elmaci AM, Yorulmaz A, et al. Prevalence and distribution of children with congenital heart diseases in the central Anatolian region, Turkey. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48:237–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hugh D, Daivid J, Robert E, Timothy F. 18th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. Moss and Adams Heart Disease Infant, Children and Adolescents. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madsen NL, Schwartz SM, Lewin MB, Mueller BA. Prepregnancy body mass index and congenital heart defects among offspring: A population-based study. Congenit Heart Dis. 2013;8:131–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2012.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman L, Ausillo D. Cecil Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tandon A, Sengupta S, Shukla V, Danda SH. Risk factors and congenital heart Disease (C) in Vellore. Indian J Biol Sci. 2010;20:253–258. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ul Haq F, Jalil F, Hashmi S, Jumani MI, Imdad A, Jabeen M, et al. Risk factors predisposing to congenital heart defects. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;4:117–21. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.84641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuciene R, Dulskiene V. Selected environmental risk factors and congenital heart defects. Medicina (Kaunas) 2008;44:827–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Øyen N, Diaz LJ, Leirgul E, Boyd HA, Priest J, Mathiesen ER, et al. Prepregnancy diabetes and offspring risk of congenital heart disease: A Nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133:2243–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fung A, Manlhiot C, Naik S, Rosenberg H, Smythe J, Lougheed J, et al. Impact of prenatal risk factors on congenital heart disease in the current era. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000064. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roodpeyma S, Kamali Z, Afshar F, Naraghi S. Risk factors in congenital heart disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2002;41:653–8. doi: 10.1177/000992280204100903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]