Abstract

Aims

The parallel regulatory–health technology assessment scientific advice (PSA) procedure allows manufacturers to receive simultaneous feedback from both EU regulators and health technology assessment (HTA) bodies on development plans for new medicines. The primary objective of the present study is to investigate whether PSA is integrated in the clinical development programmes for which advice was sought.

Methods

Contents of PSA provided by regulators and HTA bodies for each procedure between 2010 and 2015 were analysed. The development of all clinical studies for which PSA had been sought was tracked using three different databases. The rate of uptake of the advice provided by regulators and HTA bodies was assessed on two key variables: comparator/s and primary endpoint.

Results

In terms of uptake of comparator recommendations at the time of PSA in the actual development, our analysis showed that manufacturers implemented comparators to address both the needs of regulators and of at least one HTA body in 12 of 21 studies. For primary endpoints, in all included studies manufacturers addressed both the needs of the regulators and at least one HTA body.

Conclusions

One of the key findings of this analysis is that manufacturers tend to implement changes to the development programme based on both regulatory and HTA advice with regards to the choice of primary endpoint and comparator. It also confirms the challenging choice of the study comparator, for which manufacturers seem to be more inclined to satisfy the regulatory advice. Continuous research efforts in this area are of paramount importance from a public health perspective.

Keywords: clinical development, European Medicines Agency, health technology assessment, HTA bodies, parallel scientific advice, regulatory

What is Already Known about this Subject

Parallel scientific advice allows manufacturers to receive simultaneous feedback from both the EU regulators and health technology assessment (HTA) bodies on their development plans for new medicines.

There is evident commonality, in terms of evidence requirements between the EU regulators and HTA bodies, as well as among HTA bodies, on several aspects of clinical development.

The choice of the primary endpoint and of the study comparator are two key aspects of interest from both a regulatory and an HTA perspective.

What this Study Adds

Manufacturers tend to implement changes to the development programmes based on both regulatory and HTA advice with regards to the choice of primary endpoint and comparator.

For the choice of the study comparator, manufacturers seem to be slightly more inclined to satisfy the regulatory advice.

Parallel scientific advice can greatly facilitate the integration of both regulatory and HTA perspectives into one clinical development, potentially reconciling their data requirements.

Introduction

Similar to other major regulatory agencies, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) can give scientific advice (SA) to manufacturers on the appropriate design elements that comprise the clinical development programme of a medicinal product. This procedure aims to support manufacturers to provide adequate data for the benefit–risk assessment at the time of marketing authorization application, and thereby to facilitate the introduction of safe and effective medicines into the market 1. In addition to the regulatory SA, since 2010 EMA has been offering scientific advice in parallel with health technology assessment (HTA) bodies. Indeed this parallel regulatory‐HTA SA (PSA) allows manufacturers to receive simultaneous feedback from both the EU regulators (i.e. members of EMA Committees and Working Parties who provide advice to manufacturers, under the scientific coordination of EMA) and HTA bodies on their development plans for new medicines. Its aim is to bridge the gap between the evidence requirements for different decision makers and it can theoretically be initiated at any point in the developmental lifecycle of medicines, although it is often requested before the development programme has reached the pivotal phase. According to this process, a manufacturer submits a briefing document that outlines the clinical development plans for the new medicinal product, together with a set of specific questions addressed to the regulators and the HTA bodies and its own position for each question. Of note, for each procedure the manufacturer selects a set of HTA bodies of choice, which voluntarily participate in the procedure. Furthermore, as part of this process, the manufacturer will meet with both the regulators and HTA bodies representatives during a face to face discussion meeting.

Our previous analysis explored the level of overall agreement between EU regulators and HTA bodies, as well as among HTA bodies, reached through the process of PSA 2. The analysis showed clear commonality, in terms of evidence requirements, between the EU regulators and participating HTA bodies as well as among HTA bodies, on most aspects of clinical development. However, whether PSA leads to changes in clinical trial design remained unexplored. Indeed, while previous research on the process of regulatory SA has shown that the uptake of SA recommendations was correlated with marketing authorization application success 3, 4, the degree of the uptake of PSA is still an uncovered research area.

Based on these considerations and following up our previous analysis, the primary objective of the present study was to investigate whether the scientific advice provided by EU regulators and HTA bodies, during the process of PSA, is integrated in the clinical development programme for which the advice was sought. In particular, we explore manufacturers' response with respect to the advice received on the choice of the primary endpoint and of the comparator in their clinical trials, which represent two key aspects of interest from both a regulatory and an HTA perspective.

Methods

A protocol was drafted, discussed and agreed by coauthors in advance of the study execution predefining variables, data collection and analysis.

Data collection

The first step of this research was the extraction of the advice provided by the regulators and the HTA bodies for each procedure. For this purpose, the minutes of discussion meetings held at the EMA between 1 September 2010 – when parallel regulatory‐HTA SA was first launched – and 1 May 2015 – when the cut‐off date for data extraction was set – were used. All minutes were prepared by the manufacturers and then provided to the EMA. Only the recommendations related to the choice of the primary endpoint and the comparator were extracted. By comparator, we refer to either a placebo or an active control (or both, depending on the number of study arms) intervention in the control arm. In addition, information on the primary endpoint and the comparator initially proposed by the manufacturer at the time of the application was extracted from the briefing document.

The second step was tracking the development of all the clinical studies for which the PSA had been sought and in extracting information on the primary endpoint and comparator used in such studies. Three different sources were used: the EU Clinical Trial Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/), the National Institute of Health portal for clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) and the AdisInsight database (http://adisinsight.springer.com). The cut‐off date for data retrieval was 31 December 2016. Data were checked across the three databases to ensure accuracy and consistency. Clinical studies were tracked and coded regarding their development status as: planned, recruiting, ongoing, completed, withdrawn or not started.

Considering that within one procedure, the manufacturer could request advice for more than one study, the unit of analysis was each individual clinical study for which the advice was sought.

For the different steps of data collection two standardized forms were prepared. A pilot test based on three randomly chosen procedures was performed to test the process of data collection.

Data analysis

The rate of uptake of the advice provided by regulators and HTA bodies was assessed on two key variables: the primary endpoint and the comparator/s. Indeed, the analysis compared the primary endpoint and comparator/s recommended by the regulators and by the HTA bodies for each study with those used by the manufacturer during the actual clinical development. Advice uptake was assessed considering the following possible situations: (i) the manufacturer implemented in the study design only what was requested by the regulators; (ii) the manufacturer implemented only what was requested by the HTA bodies; (iii) the manufacturer implemented what requested by both regulators and HTA bodies; or (iv) the manufacturer did not take into account the advice of either. This was expressed as a Yes/No dichotomy. For cases where manufacturers followed both the regulatory and the HTA advice, two separate categories were created: (i) implementation of both the regulatory advice and the advice of at least one of the HTA bodies involved in the procedure; (ii) implementation of both the regulatory advice and the advice of >50% of the participating HTA bodies. These two categories were not mutually exclusive. Indeed, the same study could be included in both, in case, for example, the primary endpoint implemented by the manufacturer had been advised by the regulators and by two out of three HTA bodies.

Additionally, changes between the primary endpoint/comparator initially proposed by the manufacturer in their scientific advice request and those eventually chosen for the clinical development were analysed to have an approximate idea of the overall impact of the advice on manufacturer's final decisions.

G.T. and I.L. extracted the data and assessed the uptake of the regulatory and HTA recommendations into the related existing clinical trials. A.S., S.G. and E.G. independently conducted the same assessment in a blinded fashion. The outcomes of the different assessments were then disclosed and discussed. In case of disagreements, the final decision was made through a consensus process reached following discussion.

The following studies were excluded from the analysis: (i) those with no ongoing/completed clinical development at the time of data extraction; (ii) those for which questions on primary endpoint and/or comparator were not posed by the manufacturer to HTA bodies and regulators; (iii) those for which the HTA advice on primary endpoint and/or comparator/s was not available in the meeting minutes.

Results

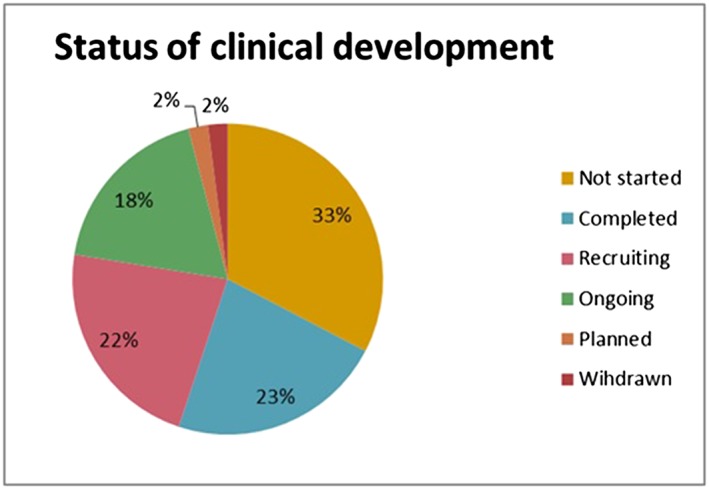

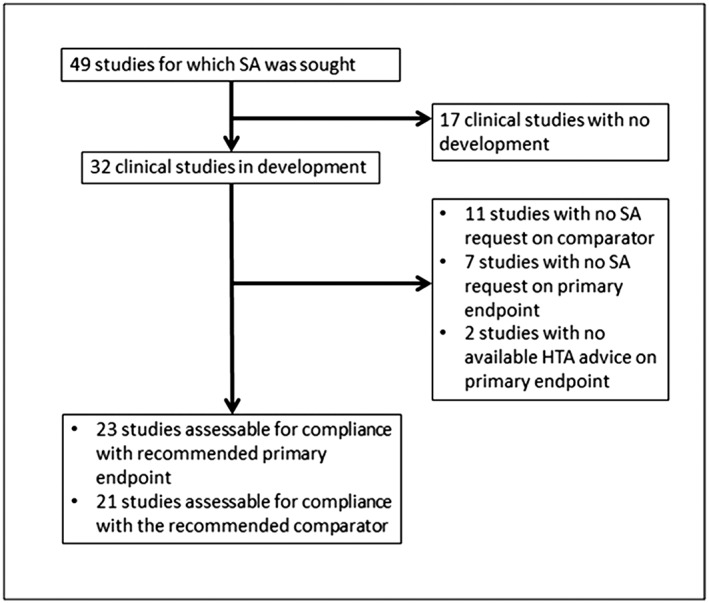

Overall, 31 PSA procedures were included in the analysis. The median number of HTA bodies involved per procedure was three, ranging between one and five. Eight different HTA bodies participated in parallel scientific advice: the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (involved in 90% of all parallel advice procedures), followed by the German Federal Joint Committee (G‐BA; 65%), Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA; 45%), Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (TLV; 35%), National Authority for Health (France; HAS; 19%), Main Association of Austrian Social Security Institutions (HVB; 10%), Catalan Agency for Health Quality and Assessment (AQuAS; 10%), and National Institute for Sickness and Invalidity Insurance (INAMI; 3%). Within those procedures, advice was sought for 49 clinical studies: two were phase I/II trials; eight were phase II trials; 38 were main pivotal confirmatory phase III trials; and one was a phase II/III trial. Out of 49 studies, 11 were completed, nine were ongoing, 11 were recruiting patients, one was still planned, 16 were not started and one was withdrawn (Figure 1). For the studies that had not yet been started, the advice had been requested for four studies in 2011, four in 2012, six in 2013, one in 2014 and one in 2015. The clinical studies eligible for the assessment of the advice uptake were the ones with an existing development and that were classified in this analysis as planned, ongoing, recruiting or completed, resulting in a sample of 32 clinical studies. We excluded from the analysis products for which manufacturers did not request any advice on the primary endpoint (n = 7) or on the comparator (11) (or alternatively requested advice only on one of the two study variables) and two studies for which no information on the advice provided by the HTA bodies was available in the minutes of the discussion meeting. As a result, the overall number of studies eligible for the analyses was 23 for the assessment of manufacturer's advice uptake for the primary endpoint and 21 for the assessment of manufacturer's advice uptake for the comparator (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Status of clinical developments for which parallel advice was sought (as of 31 Dec 2016) – Absolute values. Source: EU Clinical Trial Register, the US portal http://clinicaltrials.gov and the AdisInsight database (http://adisinsight.springer.com/)

Figure 2.

Flowchart. SA, scientific advice

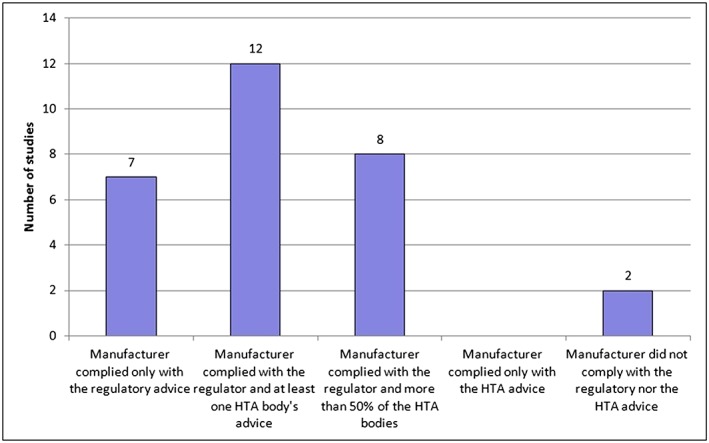

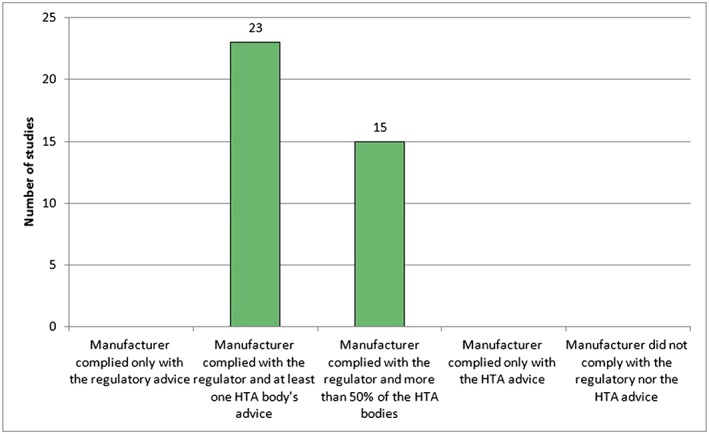

In terms of uptake of the comparator recommendations at the time of PSA in the actual development, our analysis showed that manufacturers implemented comparators to address both the needs of regulators and of at least one HTA body in 12 out of 21 studies (almost 60%). Studies for which manufacturers followed the regulators' and >50% of the HTA bodies' advice were 8/21 (38%), while those following exclusively the regulatory advice were 7/21 (about 30%). Only in two studies did the manufacturer not take up recommendations, neither from the regulators nor from the HTA advice. It was found that changes were never implemented solely on the basis of the HTA advice (Figure 3, Supporting Information Table S1). For the primary endpoint in all included studies (23 out of 23) manufacturers implemented both the requests of the regulators and at least one HTA body (Figure 4, Supporting Information Table S1). In 15 studies out of those 23 the manufacturer complied with the advice of both the regulators and >50% of the HTA bodies.

Figure 3.

Uptake of comparator recommendations in clinical developments. The category of compliance with at least one health technology assessment (HTA) body's advice and the category of compliance with >50% of the HTA bodies are not mutually exclusive

Figure 4.

Uptake of primary endpoint recommendations in clinical developments. The category of compliance with at least one health technology assessment (HTA) body's advice and the category of compliance with >50% of the HTA bodies are not mutually exclusive

Additionally, in 17 out of 23 studies (74%), the manufacturer used a different primary endpoint from the one initially proposed in the scientific advice request, while in 17 out of 21 studies (81%) the manufacturer opted for a comparator that was different from that initially proposed.

Discussion

This is a follow‐up analysis of previous research conducted on PSA about the level of agreement between regulatory and HTA advice, adding further information on this process of multi‐stakeholder interaction. One of the key findings of this analysis is that manufacturers tend to implement changes to the development programme based on both the regulatory and the HTA advice with regards to the choice of the primary endpoint and the comparator. This is highly consistent with the strong commonality in terms of evidence requirements between the EU regulators and participating HTA bodies, as well as among HTA bodies, which emerged in our previous analysis 2. The implementation of comparators to address both regulators' and HTA needs was made in 60% of the studies. This suggests that, even on a controversial aspect such as the choice of the study comparator, the parallel procedure facilitates the identification of different requirements by the stakeholders and allows manufacturers to include both the regulatory and HTA perspectives into their revised clinical development plan. However, it confirms that there is a difference between the implementation of the advice for the primary endpoint (23/23) vs. the advice provided for the comparator (12/21). This is probably due to the challenging choice of the study comparator, for which manufacturers seem to be slightly more inclined to satisfy the regulatory advice. A possible explanation may be that manufacturers are aware that the submission of indirect comparisons to HTA bodies is usually permitted to assess the additional benefit of the new drug. It is noteworthy that HTA bodies take differing approaches with regard to the comparators. Some accept established practice and this can vary between national jurisdictions, while some require the comparator options to be limited to licensed therapies, which may vary from established practice, particularly in disease areas where the comparator has been in longstanding use.

In general, this raises the issue of the different remits and evidence requirements of regulators and HTA bodies – the former focusing on the benefit/risk assessment of a product while the latter base their decisions on different criteria across countries, ranging from unmet medical needs to the relative effectiveness and safety of the drug, the drug price, the budget impact and/or the cost‐effectiveness 5. A recent analysis of anticancer drugs approved by EMA showed the limited evidence on survival and quality of life gains at the time of regulatory approval 6. Such findings have stimulated further debate on the need to identify the added value of new medicines, which becomes particularly important when reimbursement decisions on highly expensive drugs are taken. Parallel discussion could be particularly important in furthering the understanding and debate on situations such as cancer drug development when it is hard to show a clear effect on survival or quality of life and it is more feasible to demonstrate a benefit on the basis of other endpoints.

Furthermore, the key role of synergies and collaborations between regulators and HTA bodies, while still acknowledging their different remits and aims, has been discussed in a recent Reflection Paper of the EU HTA network, which identified PSA as a strategic activity to generate evidence suitable both for regulatory and HTA needs 7. Of note, PSA has seen an increasing participation of patient representatives expressing their views on aspects of the development of relevance to them, such as for example the tools to measure quality of life 8.

The fact that about 30% of the studies included in our sample (16/49) were not started leads to different possible interpretations. Discontinuation of clinical development following PSA may be due to a lack of commercial interest, to economic or scientific reasons. Alternatively, a clear red light message received during the process of parallel advice, might have discouraged manufacturers from continuing their clinical development; however, there is no information currently on the reasons behind this statistic. Indeed, this procedure can guide applicants to invest resources in viable developments and to avoid exposure of patients to possibly ineffective medicines, which is extremely beneficial from a public health perspective.

A limitation of the analysis was that it was based on the minutes of the discussion meetings prepared by manufacturers, which could reflect their interpretation and understanding of the discussion. Another potential limitation was the subjectivity of the assessment of the advice uptake into the clinical developments, although the involvement of different reviewers in a blinded fashion should have minimized this bias. Furthermore, the assessment of uptake of advice was exclusively based on two variables only. However, since questions on primary endpoint and choice of comparator are usually those most commonly requested in the scientific advice applications, this pragmatic approach was adopted to ensure an adequate sample for the analysis. It is also noteworthy that data are reflective of the HTA bodies that voluntarily took part in each procedure and thus a selected sample. However, participating HTA bodies are those most frequently giving advice to manufacturers 9.

Of note, EMA's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommended granting marketing authorizations for three products in the sample analysed. For two of these products a positive reimbursement decision has been made for the indication seeking advice in almost all the HTA bodies co‐authoring this research (seven and eight out of nine), while HTA appraisal is still ongoing in most countries for the remaining product (six out of nine).

Conclusions

In conclusion, this analysis indicates that the PSA procedure can greatly facilitate the integration of both regulatory and HTA perspectives into one clinical development, potentially reconciling their data requirements. Once more products receiving PSA are available for HTA appraisals and reimbursement decisions, comparative analyses evaluating the impact of this procedure on patient's access will be possible. In the meantime, we believe that continuous research efforts in this area are of paramount importance from a public health perspective.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

The views expressed in this article are the personal views of the authors and may not be understood or quoted as being made on behalf of, or reflecting the position of, any national competent authority, the EMA, or one of its committees or working parties.

Supporting information

Table S1 Additional supporting information: analysis of primary endpoint and comparator uptake

Tafuri, G. , Lucas, I. , Estevão, S. , Moseley, J. , d'Andon, A. , Bruehl, H. , Gajraj, E. , Garcia, S. , Hedberg, N. , Massari, M. , Molina, A. , Obach, M. , Osipenko, L. , Petavy, F. , Petschulies, M. , Pontes, C. , Russo, P. , Schiel, A. , Van de Casteele, M. , Zebedin‐Brandl, E.‐M. , Rasi, G. , and Vamvakas, S. (2018) The impact of parallel regulatory–health technology assessment scientific advice on clinical development. Assessing the uptake of regulatory and health technology assessment recommendations. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 84: 1013–1019. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13524.

Footnotes

In 2017 a new EUnetHTA/EMA platform on evidence generation interactions was launched (http://www.eunethta.eu/sites/default/files/Guidance%20on%20Parallel%20Consultation.pdf).

References

- 1. Scientific advice and protocol assistance, EMA website. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/general/general_content_000049.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05800229b9 (last accessed September 2017)

- 2. Tafuri G, Pagnini M, Moseley J, Massari M, Petavy F, Behringet A, et al How aligned are the perspectives of EU regulators and HTA bodies? A comparative analysis of regulatory‐HTA parallel scientific advice. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016; 82: 965–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Regnstrom J, Koenig F, Aronsson B, Reimer T, Svendsen K, Tsigkos S, et al Factors associated with success of market authorisation applications for pharmaceutical drugs submitted to the European Medicines Agency. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 66: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hofer MP, Jakobsson C, Zafiropoulos N, Vamvakas S, Vetter T. Regulatory watch: impact of scientific advice from the European Medicines Agency. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015; 14: 302–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ref van Nooten F, Holmstrom S, Green J, Wiklund I, Odeyemi IA, Wilcox TK. Health economics and outcomes research within drug development: challenges and opportunities for reimbursement and market access within biopharma research. Drug Discov Today 2012; 17: 615–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis C, Naci H, Gurpinar E, Poplavska E, Pinto A, Aggarwal A. Availability of evidence of benefits on overall survival and quality of life of cancer drugs approved by European Medicines Agency: retrospective cohort study of drug approvals 2009‐13. BMJ 2017; 359: j4530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. HTA Network Reflection Paper on “Synergies between regulatory and HTA issues on pharmaceuticals”. European Commission, Directorate General for Health and Food Safety. Brussels, 10 November 2016.

- 8. European Medicines Agency's interaction with patients, consumers, healthcare professionals and their organisations. Annual report 2016 (15 June 2017, EMA/260003/2016). Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2017/06/WC500229514.pdf

- 9. Report of the pilot on parallel regulatory‐health technology assessment scientific advice, (EMA/695874/2015), Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2016/03/WC500203945.pdf (accessed January 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Additional supporting information: analysis of primary endpoint and comparator uptake