Abstract

Background

The development of animal models that approximate human frailty is necessary to facilitate etiologic and treatment-focused frailty research. The genetically altered IL-10tm/tm mouse does not express the antiinflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10) and is, like frail humans, more susceptible to inflammatory pathway activation. We hypothesized that with increasing age, IL-10tm/tm mice would develop physical and biological characteristics similar to those of human frailty as compared to C57BL/6J control mice.

Methods

Strength, activity, serum IL-6, and skeletal muscle gene expression were compared between age-matched and gender-matched IL-10tm/tm mice on C57BL/6J background and C57BL/6J control mice using a longitudinal design for physical characteristics and cross-sectional design for biological characteristics.

Results

Strength levels declined significantly faster in IL-10tm/tm compared to control mice with increasing age. Serum IL-6 levels were significantly higher in older compared to younger IL-10tm/tm mice and were significantly higher in older IL-10tm/tm compared to age- and gender-matched C57BL/6J control mice. One hundred twenty-five genes, many related to mitochondrial biology and apoptosis, were differentially expressed in skeletal muscle between 50-week-old IL-10tm/tm and 50-week-old C57BL/6J mice. No expression differences between IL-10tm/tm age groups were identified by quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Conclusion

These physical and biological findings suggest that the IL-10tm/tm mouse develops inflammation and strength decline consistent with human frailty at an earlier age compared to C57BL/6J control type mice. This finding provides rationale for the further development and utilization of the IL-10tm/tm mouse to study the biological basis of frailty.

Keywords: Frailty, Mouse model

Frailty in older adults has been characterized as a syndrome of weakness, declines in activity, weight loss, and vulnerability to adverse health outcomes (1–3). Although recent studies have identified increased inflammatory mediators and decreased muscle-related hormones as important correlates of frailty and adverse health outcomes in older adults, etiological mechanisms for frailty have not been identified (4–11). Given the influence of frailty on the health and well-being of aging adults, and the inherent difficulty associated with performing biological studies in frail and vulnerable aging humans, the development of animal models for frailty represent an important next step toward the development of etiologic and intervention-focused studies on frailty (12). To develop animal models for frailty, researchers have suggested that the models should display the common signs and symptoms of human frailty, including muscle weakness, decreased activity, weight loss, inflammation, and hormonal and muscle changes. In addition, these signs and symptoms should develop first later in the life span and not be attributable to specific disease states (12).

The interleukin 10 homozygous deletion mouse (IL-10tm/tm) produces none of the antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10, which in turn leads to increased expression of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB)-induced inflammatory mediators (13–15). Although earlier studies demonstrated that these mice were vulnerable to inflammatory bowel diseases, growth retardation, anemia, and early mortality, subsequent studies of IL-10tm/tm mice maintained in barrier conditions revealed minimal evidence for these conditions and near normal survival rates (16). Given this background and the knowledge that chronic activation of inflammatory mediators likely influence frailty in older adults, we hypothesized that IL-10tm/tm mice would become weaker, thinner, and less active and that they would develop increased levels of IL-6 and altered skeletal muscle gene expression at older ages compared to age- and gender-matched C57BL/6J background control mice.

Methods

Specific pathogen free (SPF) IL-10–deficient B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn (IL-10tm/tm) mice fully backcrossed on C57BL/6J background and age- and gender-matched C57BL/6J background mice were used for this study (16).

All mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and were maintained under barrier conditions to prevent pathogen contact (15–17). Each mouse received an ear tag with a specific identification number to ensure correct longitudinal data collection. Genotype for each mouse was confirmed using a previously developed polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP) assay http://jaxmice.jax.org/pub-cgi/protocols/protocols.sh?objtype=protocol&protocol_id=356.

Mice were housed in Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International–accredited facilities in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were housed in 75-square-inch high temperature polycarbonate shoebox cages in ventilated racks (Allentown Inc., Allentown, NJ) containing autoclaved corncob bedding (Harlan Teklad, Indianapolis, IN), autoclaved mouse chow 2018SX (Harlan Teklad), and reverse-osmosis–filtered hyperchlorinated water dispensed through an in-cage automatic watering system (Edstrom Industries, Waterford, WI). Rooms were maintained at 72°F ± 2°F on a 14-hour light/10-hour dark cycle with automated monitoring by Siemens Building Technologies, Inc. (Zurich, Switzerland). Cages were sanitized every 2 weeks in laminar airflow change stations (The Baker Co., Sanford, ME) using MB-10 disinfectant (Quip Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, DE).

Colonies were monitored for infection through one sentinel cage per rack (70 cages) exposed to soiled bedding from every cage and were tested on a rotating schedule so that each rack was tested every 4 months. The following pathogens were excluded: ecto- and endoparasites, mouse hepatitis virus, epidemic diarrhea of infant mice, Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus, mouse parvovirus I, mouse minute virus, mouse adenovirus type 2, ectromelia virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, Mycoplasma pulmonis, pneumonia virus of mice, reovirus, Sendai virus, and mouse cytomegalovirus. Additional PCR testing of fecal material was performed to rule out Helicobacter species in these mice.

For longitudinal measurement of weight, activity, and strength, 10 40-week-old female C57BL/6J control and 10 40-week-old female IL-10tm/tm mice were kept at least 1 month in barrier conditions before data were collected to minimize shipping-related stimulation of inflammation. Phenotypic data were collected monthly through age 18 months. Weight was measured using a PB3002 Delta Range balance (Mettler Scales, Toledo, OH). Muscle strength was measured monthly with a Grip Strength Meter (Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) with a sensor range of 0–500 grams, and accuracy of 0.15% (18). Each mouse was held by the tail and allowed to grasp the apparatus with front paws while steady pressure was applied to the tail, and the measurement was taken just before release (maximum tensile force). Five measurements were averaged. For monthly activity measurements, each mouse was placed alone into a separate cage beginning at age 14 months, and movements were recorded by an observer who was unaware of the genotype of the mouse. Traveling activity was measured by counting the number of times a mouse crossed completely over the midline of the cage during a 5-minute period. Standing activity (rearing behavior) was measured by counting each time the mouse balanced itself on its hind paws while extending its body vertically onto the wall of the cage or without cage support during a 5-minute period. A linear mixed-effects model was fitted for each of the four measurements to study the differences in those measurements between C57BL/6J control and IL-10tm/tm mice. Each model included fixed effects of time, genotype indicator and interaction term between time and genotype, and random effects.

IL-6 levels were compared between 8-week-old IL-10tm/tm (n = 6) and C57BL/6J control mice (n = 4), and between 50-week-old IL-10tm/tm (n = 14) and C57BL/6J control mice (n = 25) using a cross-sectional design. All 8–week-old mice were killed by cervical dislocation, blood was collected from the heart and allowed to clot, and serum was stored at −80°C. Skeletal muscle was dissected immediately from the hind limbs and placed in liquid nitrogen for gene expression experiments. Blood for IL-6 assay was obtained from tail snips in all but eight of the 50-week-old mice, and serum was stored at −80°C. A subset of four older mice from each group was killed using cervical dislocation, blood was collected from the heart, and hind-limb skeletal muscle was harvested and stored in liquid nitrogen for gene expression experiments. IL-6 was quantified from stored serum samples using a Quantikine mouse solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) IL-6 kit with sensitivity to 1.3 pg/mL per manufacturer’s protocol (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Least squares means were calculated to test the significance of difference between groups, with multiple comparison adjusted using the Tukey method.

Differential gene expression in skeletal muscle was measured in three 50-week-old IL-10tm/tm mice and three 50-week-old C57BL/6J mice using the National Institute of Aging (NIA) Mouse 17K Microarray (19). Five micrograms of total RNA for each sample was radiolabeled with [33P]-labeled deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) in a reverse-transcription (RT) reaction. Membranes are hybridized with α-33P-dCTP–labeled complementary DNA (cDNA) probes (http://www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/rrb/dna.htm). Microarrays were exposed to phosphorimager screens for 3 days, and scanned in a Molecular Dynamics STORM Phosphor-Imager (Sunnyvale, CA) at 50-µm resolution. ArrayPro software (MediaCybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) was used to convert the hybridization signals from the image into raw intensity values, and data were transferred into spreadsheets predesigned to associate the ArrayPro data format to the correct gene identities.

Normalization of raw intensity data for each experiment was achieved by calculating the average intensity for each individual data set, followed by calculation of the average of the averages for each group. This grand average was used as the basis for the computation of normalization factors that were subsequently applied to each experiment. Raw intensity data for each experiment were log10 transformed and then used for the calculation of z scores by subtracting the average gene intensity from the raw intensity data for each gene and dividing that result by the standard deviation (SD) of all measurement intensities (20). The significance of calculated z differences is directly inferred from measurements of the SD of the overall z difference distribution. Differential gene expression was validated in a subset of six genes chosen to represent a range of differential expression, both positive and negative, and a range of gene function. Quantitative PCR was performed using RNA extracted from hind-limb skeletal muscle from both age groups and both genotypes by the threshold cycle method normalized for the housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphage dehydrogenase (21) with an Mx-3000P Real Time PCR System Instrument and SYBR Green fluorescence reagents (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, CA) using primers displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Genes With Segment Length in Base Pairs and Primers Used in Q-PCR Experiments

| Fos-like antigen 1 (Fosl1) (287 bp) |

| 5′-TGA AGA GCT GCA GAA GCA GAA GGA-3′ |

| 5′-AGC AAG GTT CTG GTG TGC TAG GAT-3′ |

| Activating transcription factor 3 (AFT3) (127 bp) |

| 5′-CGA AGA CTG GAG CAA AAT GAT G-3′ |

| 5′-CAG GTT AGC AAA ATC CTC AAA TAC-3′ |

| Phosphatidylserine receptor (Ptdsr) (300 bp) |

| 5′-GTT CCA GCT CGT CAG ACT CG-3′ |

| 5′-TGC CCC TAA GAC ATG ACC AC-3′ |

| SH3-domain GRB2-likeB1 (Endophilin) (Sh3glb1) (398 bp) |

| 5′-AGA CTG GAT TTG GAT GCT GC-3′ |

| 5′-AGG TCA TTG AGG TTA GAA GG-3′ |

| Metallothionein 1 (Mt1) (137 bp) |

| 5′-CTC CGT AGC TCC AGC TTC AC-3′ |

| 5′-AGG AGC AGC AGC TCT TCT TG-3′ |

| Requiem (304 bp) |

| 5′-CAT GAA AGT TGG AAG CAG AGC-3′ |

| 5′-GTG GAG CAC AAC ATG TGA ATG-3′ |

| Gl.yceraldehyde-3-phosphage dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (236 bp) |

| 5′-TTC ACCACC ATG GAG AAG GC-3′ |

| 5′-GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT CAT GA-3′ |

Note: Q-PCR = quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Results

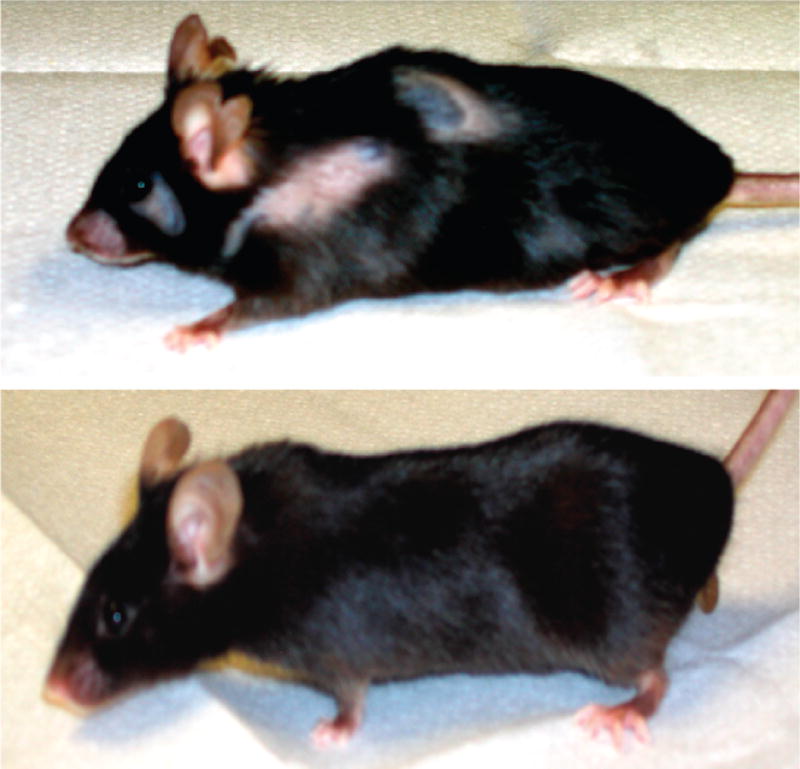

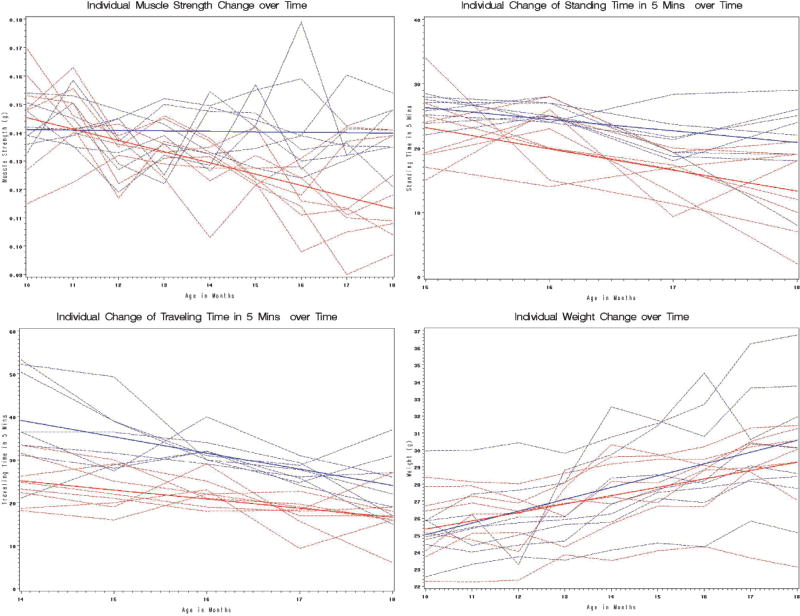

Although there was no difference in appearance between the strains at age 12 months, hair loss was increasingly apparent by age 15 months in the IL-10tm/tm mice (Figure 1). Differences by mouse strain in stength, activity, and weight measures are represented graphically in Figure 2. Although there is no significant difference in muscle strength between the IL-10tm/tm group and control group at baseline (10 months), the linear mixed effects model demonstrated that the IL-10tm/tm group’s muscle strength declined significantly faster than that of control group, with an estimated time–genotype interaction of −0.0038 and p value < .0001 (Table 2). Table 2 also shows that traveling activity was significantly different at age 14 months (estimate −22.50 with p value < .005), but the difference in the rate of decline over time was not significant (p value = .079). Standing activity was not different at age 15 months between the two groups. Although the IL-10tm/tm group had a faster decline in standing activity than the control mice, this difference was not significant (Table 2, estimate −1.48, p value = .17). Both groups of mice gained weight between age 10 months and age 18 months, and the IL-10tm/tm group had a weight gain slower than the control group, but this difference between groups was not statistically significant (Table 2, estimate −0.20, p value = .19). Mortality was not different between the groups, with two mice from each group dying between ages 15 months and 18 months of unknown causes.

Figure 1.

Photographs of 18-month old IL-10tm/tm mice (top) and C57BL/6J control strain (bottom) at age 18 months.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal muscle-related and weight-related phenotypic differences between female IL-10tm/tm (n = 10, red) and C57BL/6J control (n = 10, blue) mice by age in months. Individual observations are plotted with predicted means from mixed effects model.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates Using Mixed Effects Model

| IL-10tm/tm | Time * IL-10tm/tm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Outcome | Estimate (SE) | p Value | Estimate (SE) | p Value |

| Muscle strength | 0.0080 (0.0042) | .080 | −0.0038 (0.00075) | <.0001* |

| Traveling time | −22.50 (6.72) | .005* | 1.68 (0.94) | .079 |

| Standing | 5.79 (8.09) | .49 | −1.48 (1.07) | .17 |

| Weight | 0.53 (0.86) | .54 | −0.20 (0.15) | .19 |

Notes:

Statistically significant p value.

SE = standard error.

No significant difference was identified in mean serum IL-6 levels between 8-week-old control mice (n = 4) and IL-10tm/tm mice (n = 6) (1.53 ± 0.95 vs 0.62 ± 0.22 pg/µL, adjusted p value = .99) (Table 3). Fifty-week-old IL-10tm/tm mice (n = 14) had significantly higher levels of serum IL-6 than did 50-week-old control mice (n = 25) (22.31 ± 18.96 vs 5.96 ± 3.62 pg/µL), adjusted p value < .0001). We also found a significant difference between 8-week-old IL-10tm/tm mice and 50-week-old IL-10tm/tm mice (adjusted p value < .001), but no significant difference between 8-week-old and 50-week-old control mice (adjusted p value = .88).

Table 3.

Difference in Mean Serum Interleukin 6 (IL-6) Levels Between Age and Genotype Groups

| Comparison p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Genotype and Age | Mean (SD) | IL-10tm/tm 8 wk |

IL-10tm/tm 50 wk |

Control 8 wk |

Control 50 wk |

| IL-10tm/tm 8 wk | 0.62 (0.22) | — | |||

| IL-10tm/tm 50 wk | 22.31 (19.68) | .001* | — | ||

| Control 8 wk | 1.54 (0.95) | .999 | .008* | — | |

| Control 50 wk | 5.96 (3.62) | .706 | .0003* | .875 | — |

Notes: Least squares means of each group were compared with multiple comparison adjusted using the Tukey method.

Statistically significant p value.

SD = standard deviation.

Eighty-four genes were found to be upregulated by at least 1.5-fold in the 50-week-old IL-10tm/tm compared to the C57BL/6J matched control mice (Table 4). Many of the upregulated genes have some known function related to either apoptosis or mitochondria. Forty-two genes were expressed at lower levels in the IL-10tm/tm mice compared to the C57BL/6J control strain. Most of these genes are related to transport of proteins and the regulation of cellular growth and maintenance (Table 4). Directionality and proportionality in 4 of 6 genes tested was confirmed in the older mice (Table 5). No age differences in expression in the skeletal muscle of these four genes were identified between 8-week-old IL10−/− and C57BL/6J mice.

Table 4.

Genes Found To Be at Least 1.5-Fold Differentially Expressed Between 50-Week-Old Female IL-10tm/tm Mice and Control Mice in Hind-Limb Skeletal Muscle

| Gene Name | Gene Symbol | z Ratio* | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SH3-domain GRB2-like B1 (endophilin) | Sh3glb1 | 4.73 | Apoptotic program |

| Moloney leukemia virus 10 | Mov10 | 4.35 | Development |

| Creatine kinase, brain | Ckb | 4.00 | Creatine kinase activity |

| ADP-ribosyltransferase (NAD+; poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase) 2 | Adprt2 | 3.49 | Base-excision repair |

| Pinin | Pnn | 3.24 | Protein interactions |

| Ubiquitin c-terminal hydrolase-related polypeptide | Uchrp | 3.16 | Ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism |

| Fos-like antigen 1 | Fosl1 | 3.13 | Regulation of transcription |

| Calnexin | Canx | 2.87 | Calcium ion storage activity |

| Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, kainate 1 | Grik1 | 2.70 | Synaptic transmission |

| Sterol-C4-methyl oxidase-like | Sc4mol | 2.70 | Fatty acid metabolism |

| Ribosomal protein L13a | Rpl13a | 2.69 | Structural constituent of ribosome |

| DEAD/H (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp/His) box polypeptide 13 (RNA helicase A) | Ddx24 | 2.62 | ATP-dependent helicase activity |

| Ubiquitin-specific protease 9, X chromosome | Usp9x | 2.53 | Ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolism |

| Adenomatosis polyposis coli | Apc | 2.52 | Wnt receptor signaling pathway |

| Solute carrier family 35 (UDP-galactose transporter), member 2 | Slc35a2 | 2.49 | Nucleotide-sugar transport |

| Cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VI a, polypeptide 1 | Cox6a1 | 2.48 | Electron transport |

| 3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | Phgdh | 2.42 | Serine biosynthesis |

| Ribosomal protein L29 | Rpl29 | 2.40 | Protein biosynthesis |

| Solute carrier family 2, (facilitated glucose transporter), member 8 | Slc2a8 | 2.25 | Fructose transport |

| Transketolase-like 1 | Tktl1 | 2.22 | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| Casein kinase 1, epsilon | Csnk1e | 2.18 | Circadian rhythm |

| Inhibitor of κB kinase β | Ikbkb | 2.17 | I-κB phosphorylation |

| Tumor rejection antigen P1A | Trap1a | 2.16 | Immune system stimulation |

| Cysteine and histidine-rich domain (CHORD)-containing, zinc-binding protein 1 | Chordc1 | 2.15 | Chaperone protein |

| High mobility group nucleosomal binding domain 2 | Hmgn2 | 2.14 | DNA packaging |

| Activating transcription factor 3 | Atf3 | 2.10 | Regulation of transcription |

| Tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, eta polypeptide | Ywhah | 2.08 | Hydroxylase activator |

| Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 1, acid lysosomal | Smpd1 | 2.06 | Carbohydrate metabolism |

| LIM and SH3 protein 1 | Lasp1 | 2.05 | Actin binding activity |

| Actinin, α 1 | Actn1 | 2.01 | Actin binding activity |

| Transmembrane 9 superfamily member 2 | Tm9sf2 | 1.99 | Transport |

| DEAD (aspartate-glutamate-alanine-aspartate) box polypeptide, Y chromosome | Dby | 1.98 | T-cell signaling |

| Rho interacting protein 3 | Rhoip3 | 1.95 | Cytoskeleton regulation |

| Aldolase 1, A isoform | Aldo1 | 1.95 | Glycolysis |

| Geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 1 | Ggps1 | 1.94 | Isoprenoid biosynthesis |

| Mannose-P-dolichol utilization defect 1 | Mpdu1 | 1.90 | Glycosylation |

| Requiem | Req | 1.88 | Apoptosis |

| Signal transducing adaptor molecule (SH3 domain and ITAM motif) 1 | Stam | 1.87 | Intracellular protein transport |

| Interleukin 1 receptor-like 1 ligand | Il1rl1l | 1.86 | Defense response |

| Transcription elongation factor A (SII), 3 | Tcea3 | 1.85 | RNA elongation |

| Jumonji | Jmj | 1.84 | Development |

| Craniofacial development protein 1 | Cfdp | 1.81 | Anti-apoptosis |

| Casein kinase II, α 1-related sequence 4 | Csnk2a1-rs4 | 1.79 | Acidic protein phosphorylation |

| Thimet oligopeptidase 1 | Thop1 | 1.77 | Peptide metabolism |

| Leukemia inhibitory factor | Lif | 1.77 | Immune response |

| Serologically defined colon cancer antigen 28 | Sdccag28 | 1.77 | Lipid sorting |

| Nuclear receptor coactivator 6 | Ncoa6 | 1.75 | Brain development |

| Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 | Eef2 | 1.74 | Translational elongation |

| Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 | Eef2 | 1.74 | Translational elongation |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, component X | Pdhx | 1.72 | Metabolism |

| Phosphatidylserine receptor | Ptdsr | 1.71 | Apoptosis |

| WW domain binding protein 4 | Wbp4 | 1.70 | Splicing protein |

| Heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase 1 | Hs2st1 | 1.70 | Polysaccharide chain biosynthesis |

| Sorting nexin 2 | Snx2 | 1.70 | Intracellular protein transport |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 9 | Tnfrsf9 | 1.69 | Defense response |

| Dynamin 2 | Dnm2 | 1.67 | Endocytosis |

| Casein kinase 1, α 1 | Csnk1a1 | 1.66 | Kinase activity |

| Ribosomal protein S6 kinase polypeptide 1 | Rps6ka1 | 1.65 | Protein amino acid phosphorylation |

| Spectrin SH3 domain binding protein 1 | Ssh3bp1 | 1.64 | Cell growth and maintenance |

| Cyclin G | Ccng | 1.63 | Mitosis |

| src family–associated phosphoprotein 2 | Scap2 | 1.63 | Negative regulation of cell proliferation |

| Polypyrimidine tract binding protein 1 | Ptbp1 | 1.62 | mRNA splicing |

| AE binding protein 1 | Aebp1 | 1.61 | Cell adhesion |

| Potassium intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily N, member 2 | Kcnn2 | 1.61 | Calmodulin binding activity |

| Cryptochrome 1 (photolyase-like) | Cry1 | 1.58 | Circadian rhythm |

| Calmodulin 3 | Calm3 | 1.57 | Protein signaling pathway |

| Solute carrier family 30 (zinc transporter), member 6 | Slc30a6 | 1.57 | Golgi to endosome transport |

| Protocadherin 18 | Pcdh18 | 1.56 | Calcium ion binding activity |

| Retinoblastoma binding protein 7 | Rbbp7 | 1.56 | Cell growth inhibitor |

| Phenylalanine-tRNA synthetase-like | Farsl | 1.56 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA aminoacylation |

| ATP-binding cassette, subfamily G (WHITE), member 4 | Abcg4 | 1.55 | Transport |

| Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 2 | Eef2 | 1.55 | Translational elongation |

| NIMA (never in mitosis gene a)-related expressed kinase 2 | Nek2 | 1.55 | Meiosis |

| Formin binding protein 3 | Fnbp3 | 1.55 | Nuclear docking site |

| Vacuolar protein sorting 41 (yeast) | Vps41 | 1.55 | Fe transport network |

| Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 1 | Arhgef1 | 1.54 | Rho protein signal transduction |

| Methyl-CpG binding domain protein 3 | Mbd3 | 1.53 | DNA methylation |

| Aspartylglucosaminidase | Aga | 1.53 | Glycoprotein catabolism |

| MAP kinase-activated protein kinase 5 | Mapkapk5 | 1.53 | Amino acid phosphorylation |

| Kinesin family member C3 | Kifc3 | 1.51 | Golgi organization and biogenesis |

| Transcription elongation factor B (SIII), polypeptide 1 (15 kd),-like | Tceb1l | −1.50 | Inhibits transcription |

| Hydroxysteroid (17-β) dehydrogenase 4 | Hsd17b4 | −1.50 | Protein targeting |

| Exportin 4 | Xpo4 | −1.54 | Intracellular protein transport |

| Hypoxia inducible factor 1, α subunit | Hif1a | −1.55 | Regulation of transcription |

| Hippocampus abundant gene transcript 1 | Hiat1 | −1.60 | Transport |

| 26S proteasome-associated pad1 homolog | Poh1 | −1.61 | Protein degradation |

| Hypothetical protein, I54 | X61497 | −1.61 | # |

| Nuclear DNA binding protein | C1d | −1.63 | Negative regulation of transcription |

| DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 3 | Dnaja3 | −1.66 | Small GTPase mediated signal transduction |

| Ribosomal protein L8 | Rpl8 | −1.69 | RNA binding activity |

| Zinc finger protein 103 | Zfp103 | −1.70 | Protein interactions |

| Msx-interacting-zinc finger | Miz1 | −1.76 | Transcription |

| Chorionic somatomammotropin hormone 1 | Csh1 | −1.77 | Growth hormone like |

| Dual-specificity tyrosine-(Y)-phosphorylation regulated kinase 1a | Dyrk1a | −1.78 | Peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation |

| Ectodermal-neural cortex 1 | Enc1 | −1.79 | Development |

| Kinesin family member 5B | Kif5b | −1.80 | Microtubule-based process |

| smt3-specific isopeptidase 1 | Smt3ip1 | −1.81 | Protein metabolism |

| Single-stranded DNA binding protein 2 | Ssbp2 | −1.82 | Regulation of transcription |

| Serine protease inhibitor 1–5 | Spi1–5 | −1.82 | Gene imprinting |

| Cell division cycle 2 homolog A (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) | Cdc2a | −1.85 | Mitosis |

| Pore forming protein-like | Pfpl | −1.87 | Cytolytic protein |

| Blocked early in transport 1 homolog (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)-like | Bet1l | −1.88 | ER vesicular transport |

| Immunoglobulin heavy chain 6 (heavy chain of IgM) | Igh-6 | −1.88 | Humoral immune response |

| Tumor differentially expressed 1, like | Tde1l | −1.89 | Apoptosis reduction |

| Fragile X mental retardation syndrome 1 homolog | Fmr1 | −1.98 | Nucleocytoplasmic shuttle |

| Lysosomal trafficking regulator | Lyst | −1.99 | Cellular defense response |

| Pumilio 2 (Drosophila) | Pum2 | −2.00 | RNA binding activity |

| Single Ig IL-1 receptor-related protein | Sigirr | −2.01 | Negative regular of IL-1 signaling |

| Metallothionein 1 | Mt1 | −2.10 | Free radical regulation |

| Nuclear receptor subfamily 5, group A, member 2 | Nr5a2 | −2.17 | Regulation of transcription |

| Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor 1 | Itpr1 | −2.21 | Calcium ion transport |

| Solute carrier family 29 (nucleoside transporters), member 2 | Slc29a2 | −2.23 | Nucleoside transport |

| Ras association (RalGDS/AF-6) domain family 5 | Rassf5 | −2.32 | Protein binding activity |

| Inhibin β-A | Inhba | −2.37 | Cell growth and/or maintenance |

| Phosphate cytidylyltransferase 1, choline, α isoform | Pcyt1a | −2.51 | Biosynthesis |

| Membrane bound C2 domain containing protein | Mbc2 | −2.59 | # |

| General transcription factor II H, polypeptide 2 (44 kd subunit) | Gtf2h2 | −2.69 | DNA repair |

| Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide A | Snrpa | −2.75 | RNA processing |

| Topoisomerase (DNA) II α | Top2a | −2.97 | DNA topological change |

| TATA box binding protein | Tbp | −3.17 | Regulation of transcription |

| G elongation factor | Gfm | −3.23 | Translational elongation |

| Long chain fatty acyl elongase | Lce | −3.63 | Fatty acid elongation |

Notes: Major gene functional categories that are expressed at higher levels in IL-10tm/tm mice include those belonging to apoptotic programs, protein catabolism programs, and inflammatory pathway activation, among others. Downregulated categories include those that regulate gene transcription and RNA processing, protect against apoptosis and free radicals, and housekeeping transport function.

Two-tailed p values between 5.24 × 10−3 and 7.43 × 10−9 for all.

No known function.

ADP = adenosine diphosphate; NAD = Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; ATP=Adenosine 5′-triphosphate; UDP=uridin 5′-diphosphate; SH3 = Src homology 3; mRNA = messenger RNA; tRNA = transfer RNA; ER = endoplasmic reticulum; IgM = immunoglobulin M; IL-1 = interleukin 1.

Table 5.

Genes Chosen for Q-PCR Validation Experiments

| Gene Name | Z Ratio from Array |

50-wk IL-10tm/tm vs 50-wk C57BL/6J |

8-wk IL-10tm/tm vs 8-wk C57BL/6J |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mt1 | −2.10 | −1.81 | Same |

| Sh3glb1 | 4.73 | 1.75 | Same |

| Fosl1 | 3.13 | 1.58 | Same |

| Ptdsr | 1.71 | 1.50 | Same |

Note Q-PCR = quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Discussion

In this study, aging IL-10tm/tm mice developed muscle weakness significantly more rapidly with increasing age than did C57/BL/6J control mice. Older, but not younger, IL-10tm/tm mice had significantly higher IL-6 levels compared to age- and gender-matched C57BL/6J mice. Skeletal muscle weakness and chronic inflammation are two of the most common physical characteristics of human frailty (1–4,6). In addition, older IL-10tm/tm mice showed evidence for the upregulation of several skeletal muscle genes related to apoptosis and mitochondrial function compared to control mice. Quantitative PCR confirmed some of these differences and suggested that these gene expression differences emerged only at older ages. Although preliminary, the findings of age-related declines in strength, increases in serum IL-6 level, and altered skeletal muscle gene expression related to apoptosis and mitochondrial function provide crucial early evidence that the IL-10tm/tm mouse may be an important animal model for both the study of human frailty and the study of the impact of chronic inflammation in aging.

The underlying biological basis for frailty is likely multisystemic and stems from age-related biological changes, genetic predisposition, and chronic disease states (12,22). The activation of IL-6-related inflammatory systems has consistently been shown to produce adverse health outcomes and frailty in older adults, and is therefore a major target of recent biological studies on aging (8). NF-κB is the critical gateway molecule to the production of inflammatory mediators such as IL-6 and is therefore an important target of etiologic investigations of frailty and other aging-related pathophysiological processes (8,14). The IL-10tm/tm mouse develops increased inflammatory signaling because it cannot produce the antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10, which normally attenuates NF-κB signaling and dampens inflammatory activation (23).

It is not clear why IL-6 levels increase only in older but not younger IL-10tm/tm mice. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from infections, chronic disease states that stimulate inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-1, and age-related increases in free radicals such as H2O2 stimulate NF-κB activation could trigger these increases in older animals (24). However, given that the study mice were kept in barrier conditions and carefully monitored for infections and chronic disease states, one can speculate that age-related increases in oxidative stress may be an important age-related trigger of NF-κB-related inflammatory activation and hence frailty in these mice.

Other etiologic mechanisms may also have played an important role in the development of differential muscle weakness in these older IL-10tm/tm mice. Apoptosis has been noted to be accelerated in some aging tissues with rapid turnover, including liver and white blood cells (25). There is also increasing evidence that inflammation-induced apoptotic pathways, specifically those related to mitochondria, are also important in age-related muscle decline (26). The biological relationship between loss of IL-10 and apoptosis has been characterized previously in liver, in part due to the loss of protection from apoptosis known to be induced by proinflammatory cytokines (27). Although this potential biologic pathway to accelerated muscle decline in frail, older adults has not yet been confirmed, the findings from this preliminary gene expression study provide rationale for the further study of apoptotic changes in the skeletal muscle of frail humans (26).

There are several factors that support the utilization of IL-10tm/tm mice in the future study of frailty. First, the development of increased inflammation and decreased strength with age is consistent with two critical components of human frailty. Second, the IL-10tm/tm mouse is relatively long lived and develops modest inflammatory changes only later in life, similar to frail humans. This late-life activation provides an important opportunity to study the longitudinal development of multisystem alterations related to inflammation, and how chronic inflammation may trigger multisystem changes. Third, of the 17,000 genes measured in the expression array, many of those altered were related to mitochondrial function and apoptosis, biological realms important in aging research.

There are also several factors that may limit the use of IL-10tm/tm mice in future studies of frailty. First, these mice are genetically altered, and the loss of the IL-10 gene may contribute to biologic changes such as apoptosis induction that are different than those observed in free-living frail humans (27). Second, because these mice must be kept in barrier conditions to prevent illness, they are also less representative of free-living frail adults (16,17). Third, although the mice do on average display increased serum IL-6 in older age groups, the wide variation in these levels suggests that undetected chronic illness may be present. Hence, any future use of this model for frailty research must include very careful monitoring for infection and chronic disease states. Other limitations of this study, not specific to this strain of mouse, include the lack of (i) fine motor measures, (ii) knowledge of estrous status, (iii) early life activity measures, (iv) food intake measurement, (v) detailed body mass index information, and (vi) males in the population. Finally, although the array data may provide important biological clues for frailty research, it is exploratory in nature and must be confirmed and extended before further etiologic studies are undertaken. Despite these limitations, the IL-10tm/tm mouse develops important physical and biological characteristics of human frailty as it ages, which support its further development as a mouse model for the study of frailty.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Aging, Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Centers, grant P30 AG021334.

Biographies

Jeremy Walston, Johns Hopkins University

Sean Leng, Johns Hopkins Medicine

Brock Beamer, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Sara E Espinoza, University of Texas Health Science Center at …

References

- 1.Fried LP, Tangen C, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2001;56A:M1–M11. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown M, Sinacore DR, Binder EF, Kohrt WM. Physical and performance measures for the identification of mild to moderate frailty. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2000;55:M350–M355. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.6.m350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chin APM, Dekker JM, Feskens EJ, Schouten EG, Kromhout D. How to select a frail elderly population? A comparison of three working definitions. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1015–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical morbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2333–2341. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leng S, Chaves P, Koenig K, Walston J. Serum interleukin-6 and hemoglobin as physiological correlates in the geriatric syndrome of frailty: a pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1268–1271. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leng SX, Cappola AR, Andersen RE, et al. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S), and their relationships with serum interleukin-6, in the geriatric syndrome of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF03324545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM, et al. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maggio M, Guralnik JM, Longo DL, Ferrucci L. Interleukin-6 in aging and chronic disease: a magnificent pathway. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:575–584. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Pahor M, et al. Inflammatory markers and physical performance in older persons: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59A:242–248. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, et al. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106:506–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR, et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2002;57A:M326–M332. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.5.m326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:991–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rennick D, Davidson N, Berg D. Interleukin-10 gene knock-out mice: a model of chronic inflammation. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;76(3 Pt 2):S174–S178. doi: 10.1016/s0090-1229(95)90144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanada T, Yoshimura A. Regulation of cytokine signaling and inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:413–421. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg DJ, Davidson N, Kuhn R, et al. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4(+) TH1-like responses. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1010–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI118861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bristol I, Mahler M, Leiter E, Sundberg JP. Il10<tm1Cgn>, an interleukin-10 gene targeted mutation. The Jackson Laboratory. [Last accessed: May 2007];JAX/Mice & Services. 1997 471 Available at: http://www.jaxmice.jax.org/library/notes/471a. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang L, Danon SJ, Grehan M, Chan V, Lee A, Mitchell H. Natural colonization with Helicobacter species and the development of inflammatory bowel disease in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Helicobacter. 2005;10:223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2005.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whittemore LA, Song K, Li X, et al. Inhibition of myostatin in adult mice increases skeletal muscle mass and strength. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:965–971. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02953-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka TS, Jaradat SA, Lim MK, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of mid-gestation placenta and embryo using a 15,000 mouse developmental cDNA microarray. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9127–9132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheadle C, Vawter MP, Freed WJ, Becker KG. Analysis of microarray data using Z score transformation. J Mol Diagn. 2003;5:73–81. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60455-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von SC, Strehlau J, Ehrich JH, Melk A. Quantitative gene expression of TGF-beta1, IL-10, TNF-alpha and Fas Ligand in renal cortex and medulla. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:573–579. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.4.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fried LP, Hadley EC, Walston JD, et al. From bedside to bench: research agenda for frailty. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2005;(31):pe24. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2005.31.pe24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schottelius AJ, Mayo MW, Sartor RB, Baldwin AS., Jr Interleukin-10 signaling blocks inhibitor of kappaB kinase activity and nuclear factor kappaB DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31868–31874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.31868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ting AY, Endy D. Signal transduction. Decoding NF-kappaB signaling. Science. 2002;298:1189–1190. doi: 10.1126/science.1079331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higami Y, Shimokawa I. Apoptosis in the aging process. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s004419900156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marzetti E, Leeuwenburgh C. Skeletal muscle apoptosis, sarcopenia and frailty at old age. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41:1234–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santiago-Lomeli M, Gomez-Quiroz LE, Ortiz-Ortega VM, Kershenobich D, Gutierrez-Ruiz MC. Differential effect of interleukin-10 on hepatocyte apoptosis. Life Sci. 2005;76:2569–2579. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]