Abstract

Objectives

To compare the abilities of teens with uncontrolled persistent asthma and their caregivers to identify inhaled medications and state correct indications for use; examine medication responsibility within dyads; and determine whether responsibility is associated with knowledge about inhaled therapies.

Design/Methods

In the baseline survey for the School-Based Asthma Care for Teens (SB-ACT) trial, we separately asked caregivers and teens to: 1) identify the teen’s inhaled asthma therapies by name and from a picture chart (complete matches considered “concordant”); 2) describe indications of use for each medication; 3) describe the allocation of responsibility for medication use within dyads. We limited analyses to dyads in which either member reported at least one rescue and one inhaled controller medication; we used McNemar and Pearson chi-square tests.

Results

136 dyads were analyzed. More caregivers than teens concordantly identified medications (63% vs 31%, p<0.001). There was no difference between caregivers and teens in the ability to state correct indications for use (56% vs 54%, p=0.79). More teens than caregivers endorsed “full teen responsibility” for rescue medication (65% vs 27%, P<0.001) and controller medication use (50% vs 15%, P<0.001). Neither concordant identification nor knowing indications for use were associated with reported medication responsibility.

Conclusion(s)

Medication responsibility within dyads of caregivers and teens with persistent asthma is not associated with knowledge about inhaled therapies. Targeting both members of the dyad with education and self-management strategies before responsibility transitions start may allow providers to avoid a missed opportunity to support these emerging stakeholders to adherence.

Keywords: asthma, childhood, primary care, prevention, responsibility, medication identification

INTRODUCTION

More than eight percent of children in the United States under the age of 18 years are diagnosed with asthma,(2) one of the most common chronic diseases of childhood. The prevalence of pediatric asthma is higher among poor, minority, and urban children, who also bear a disproportionate burden of preventable asthma-related morbidity including hospitalization, emergency department visits, and missed days of school.(3–5) Persistent asthma can be controlled in most children through daily use of controller medications such as inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).(6) Despite this, preventable morbidity levels remain high,(2) in part because of poor adherence with effective controller medications.(7)

Children with persistent asthma only use around half of all prescribed controller medication doses,(8) comparable with adherence rates observed among adults managing other chronic diseases.(9) Poor, minority, and urban children are at increased risk of non-adherence.(8, 10) Adolescents are also at particular risk of poor adherence as they develop an independence that extends to how they perceive and manage asthma.(11) Among older teens, only about 25% of controller medication doses are used as prescribed.(8) This drop in teen adherence coincides with increasing responsibility for medication use.

As children with persistent asthma get older, the responsibility for using inhaled medication gradually transfers from caregiver to child.(1) The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) statement on health care transition(12) recommends that providers start working to promote youth self-management by age 14, or sooner if appropriate on an individual basis. However, most families are not waiting until age 14 before transitioning responsibility. In fact, children share half of the responsibility for using controller medications by age 11 and have more responsibility than caregivers after age 13.(1) While many providers are following recommendations to discuss increasing teen responsibility for health care among children ages 12–17 years old,(13) they risk missing important opportunities to engage early adolescents about the asthma care responsibilities they may already be assuming. Clinical discussions of medication management are often directed solely or primarily at caregivers,(14) raising the question of whether teens are being adequately prepared to independently succeed in adherence behaviors.

The model of medication self-management(15) offers a useful framework for determining what medication knowledge and skills are necessary for adherence. After filling prescriptions, patients need to have a basic understanding of their medications in order to use them appropriately. Bailey defines medication understanding as the abilities “to name, identify, and understand how to take medications.”(15) Prior work indicates that age and developmental level may influence a child’s understanding of asthma medications, with younger children more likely to identify medications by describing physical characteristics (vs. name) and less likely to differentiate between categories of therapy.(16, 17) It is not clear whether children attain sufficient understanding of medications prior to assuming responsibility for medication self-management. One study identified an association between medication responsibility and general disease knowledge among children with asthma,(8) while another study found no association between responsibility for anti-retroviral use and regimen knowledge among children with HIV.(18) Specifically, it is unclear whether adolescents know which inhaled asthma medicines to use or when to use them by the time they are fully responsible for medication self-management.

We aimed to better understand the caregiver/teen dynamic around the knowledge of and responsibility for asthma medication use, in order to help providers educate and prepare adolescents to succeed in self-management. This study had three objectives: to compare within dyads of teens with uncontrolled persistent asthma and their caregivers the abilities to identify inhaled medications and state correct indications for use; to examine responsibility for using inhaled medications within caregiver/teen dyads; and to determine whether responsibility is associated with knowledge about inhaled therapies.

METHODS

Settings and Participants

All data are drawn from the School-Based Asthma Care for Teens (SB-ACT) trial underway in Rochester, NY. SB-ACT is a randomized controlled trial designed to promote adherence with preventive medications among urban teens with uncontrolled persistent asthma. We analyzed data from baseline surveys administered in the home during the first 2 years of the study.

Eligibility criteria for inclusion in the SB-ACT trial included a child age between 12–15 years, a physician diagnosis of asthma, persistent asthma symptoms/poorly controlled asthma based on caregiver report of symptoms, and attendance at a partner school within the Rochester, NY metropolitan area. Exclusion criteria included an inability of participants to speak or understand English, lack of access to a working phone for follow-up assessments, or if the child had another significant medical condition that could interfere with asthma assessment (e.g. congenital heart disease, cystic fibrosis, or another chronic lung disease). We limited inclusion into the current analysis to dyads in which either the caregiver or the teen reported teen use of at least one rescue and one inhaled controller medication. This decision was based on an assumption that differentiating between asthma medications would be more challenging when more than one class of inhaled medication is prescribed.

Written informed consent was obtained from all caregivers; teens provided verbal (12 year olds) or written (13–15 year olds) assent. Participating families were compensated for the time required to complete the baseline survey with a $50 grocery store gift card. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Rochester.

Measures

In the baseline survey, we asked caregivers and teens separately to identify all inhaled medications used by the teen; describe indications for use of each medication; and describe the responsibility for medication use within dyads. Further details for each of these measures are provided below. Caregivers additionally provided demographic information.

Concordant Identification

Both the teen and the caregiver individually named the teen’s inhaled asthma medications; no descriptions of medication function or examples of medication names were provided by research staff. As our objectives focus on inhaled medications, non-inhaled asthma therapy (i.e. leukotriene receptor antagonists) and adjuvant asthma therapies (i.e. allergic rhinitis medication) were not included in this assessment. Next, respondents selected the teen’s medications on a pictorial chart printed in color with visible medication names removed. We compared the provided medication names with the images selected from the chart. For individual respondents, we defined concordant identification as completely matching all reported medication names and images (yes/no).

Both generic and trade names were accepted responses, though subject to different interpretation. A generic medication name (i.e., “albuterol”) was considered to be an acceptable match for any albuterol preparation on the chart. Respondents providing trade names had to select the same trade product on the chart to be considered concordant. Most physical descriptors (e.g. device color) were not accepted as medication names when determining concordance. Patient reliance on physical descriptors to identify medication has been associated with worse outcomes,(19) and the lack of standardized actuator color among inhaled asthma medications makes physical descriptors a potentially unreliable method of identification that risks patient/provider miscommunication. The one exception to our approach was nebulizer machines: although vials of albuterol solution were included on the chart, there was no picture of the nebulizer delivery device. Any respondent who included “nebulizer” or “machine” as a medication name was accordingly not penalized for failing to select the albuterol solution; for these few subjects, the determination of concordance was made without consideration of the nebulized medications. A similar consideration was made for the few respondents who named Pulmicort™, as only nebulized albuterol solution was included on the chart.

It is important to note that we did not compare reported medications with prescription data from electronic medical records or pharmacy reports, as it was not our intent to determine whether respondents were accurate. Our goal was to examine the practical ability of respondents to identify and state indications of use for medications that the teen routinely uses.

Correct Indications for Use

To examine whether caregivers and teens understood correct indications for use of inhaled medications, we posed two close-ended questions about each identified medication. First, we asked when each medication is supposed to be used (i.e. “only as needed,” “every day,” or “other”). This question was intended to assess knowledge of medication use as prescribed by clinicians, not adherence or deviation from prescribed use. Next, we asked how each inhaled medication works (i.e. “quick relief of current symptoms,” “prevention of future symptoms,” or “other”). We defined correct indications for use as a dichotomized (yes/no) variable, with respondents needing to provide accurate indications on both of the above items for all identified medications.

For rescue medications, respondents were correct when identifying use “only as needed” for “quick relief of symptoms.” We also accepted “prevention of future symptoms” as a mechanism of action if paired with “only as needed”, as many teens are instructed to use albuterol before gym class/strenuous physical activity to prevent asthma symptoms. Correct in controller medication use was defined as “every day” use for “prevention of future symptoms.” A small number of respondents specified controller medication use “only as needed” with URI symptoms; as this practice is endorsed by some clinicians, the response was accepted if specified under “other” time for use and paired with “prevention of future symptoms.”

Responsibility for Medication Use

The baseline survey contained a 9 item scale of home asthma management tasks, including getting medication refills, avoiding triggers, and deciding when to seek asthma-related medical care. This instrument was adapted from use in previous studies of adolescent responsibility in pediatric asthma(20) and type 1 diabetes.(21) Although prior works have analyzed similar scales using summed scores, we chose to focus on two direct management items from this scale: deciding when to take as-needed (rescue) medication, and remembering to take every day (controller) medication. Three response options were available for each task: the parent/caregiver takes responsibility almost all of the time (e.g. “full caregiver responsibility”); the parent/caregiver and teen share responsibility about equally (e.g. “shared responsibility”); or, the teen takes responsibility almost all of the time (e.g. “full teen responsibility”).

Analysis

We first examined concordant identification and correct indications for use. Each measure of medication knowledge was evaluated both within dyads (comparing paired caregiver and teen knowledge) and between dyads (comparing knowledge among all caregivers or all teens). For caregiver and teen subgroups, concordant identification was additionally compared with the ability to state correct indications for use.

Next, we examined whether medication knowledge among caregivers and teens varied based on the reported level of teen responsibility. Answers to the responsibility questions were dichotomized: we compared “full teen responsibility” with a combination of “shared/full caregiver responsibility.” Two sets of analyses were performed, first using caregiver responses to responsibility questions and then using teen responses. In each set of analyses, we explored whether concordant identification or correct indications for medication use were significantly associated with “full teen responsibility,” for either rescue or controller medications.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses with re-categorized responsibility variables. In one set of analyses, we compared “shared/full teen responsibility” with “full caregiver responsibility” to examine whether the presence of any teen responsibility was associated with concordant identification or correct indications for use; in a separate set of analyses, answers to responsibility questions were left ungrouped in order to test for an overall trend.

All analyses were performed using STATA (version 12.0). We used descriptive statistics for demographic data, and bivariate analyses for comparisons between concordant identification, correct indications for use, and medication responsibility. Specifically, we used McNemar chi-square tests for within-dyad comparisons (i.e., concordant identification, indications for use, responsibility for medication use) and Pearson chi-square tests for between-dyad comparisons (i.e., concordant identification vs indications for use, responsibility for use vs medication knowledge). McNemar exact P values were used for instances of small cell sizes. A 2-sided alpha <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participants

We enrolled 176 dyads during the first two years of SB-ACT from November 2014 through December 2016 (enrollment rate 79% of 223 eligible children). Teen use of at least one rescue and one controller medication was reported by either the caregiver or the teen in 136 dyads (77% of enrollees). The overall sample for this analysis was 54% male, 60% Black, and 35% Hispanic; the average age of enrolled children was 13.6 years, and a majority (79%) were enrolled in public health insurance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

|

All Subjects (n = 136) |

|

|---|---|

|

| |

| Teen Demographics | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 13.6 (1.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 73 (53.7%) |

| Female | 63 (46.3%) |

| Race | |

| White | 11 (8.1%) |

| Black | 81 (59.6%) |

| Other | 44 (32.3%) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 47 (34.6%) |

| Insurance Coverage | |

| Public | 107 (78.7%) |

| Private | 26 (19.1%) |

| Other | 3 (2.2%) |

| Caregiver Demographics | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 40.6 (8.3) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 14 (10.3%) |

| Female | 122 (89.7%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single/Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 107 (78.7%) |

| Domestic Partner/Married | 29 (21.3%) |

| Education Level | |

| High School Graduate or Less | 86 (63.2%) |

| Beyond High School | 50 (36.8%) |

| Primary Language Spoken at Home | |

| English | 116 (85.3%) |

| Spanish | 20 (14.7%) |

Measures

Concordant Identification

Caregivers were twice as likely as teens to provide medication names that matched perfectly with the images they selected (63% vs. 31%, p < 0.001); teens were significantly more likely to concordantly identify medications if they had a caregiver who concordantly identified medications. Part of this discrepancy may be due to a difference observed in the way that caregivers and teens identified medications: when asked to name medications, teens were significantly more likely than caregivers to provide a color description (e.g. “orange inhaler”) instead of a medication name (34% vs. 4%, p < 0.001).

Correct Indications for Use

Slightly more than half of all participants were able to state correct indications for medication use, with no difference in accuracy observed between caregivers and teens (56% vs. 54%, p = 0.79). It is worth noting that over 40% of all respondents could not correctly state indications for use of the medications they identified.

Comparing Concordant Identification with Correct Indications for use

Concordant identification of medications was significantly associated with the ability to state correct indications for use both caregivers (OR 5.25, 95% CI: 2.70–12.22) and teens (OR 3.02, 95% CI: 1.52–6.02) (Table 2). Compared with teens who described one or more device colors when asked to name medications, teens who only provided medication names were significantly more likely to state correct indications for use (OR 2.67, 95% CI: 1.39–5.13).

Table 2.

Concordant Identification vs Indications for Use

| Concordant Identification | Correct Indications for Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | P-value | ||

|

| ||||

| Teen | No | 51 (81%) | 43 (58%) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 12 (19%) | 31 (42%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Caregiver | No | 35 (58%) | 16 (21%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 25 (42%) | 61 (79%) | ||

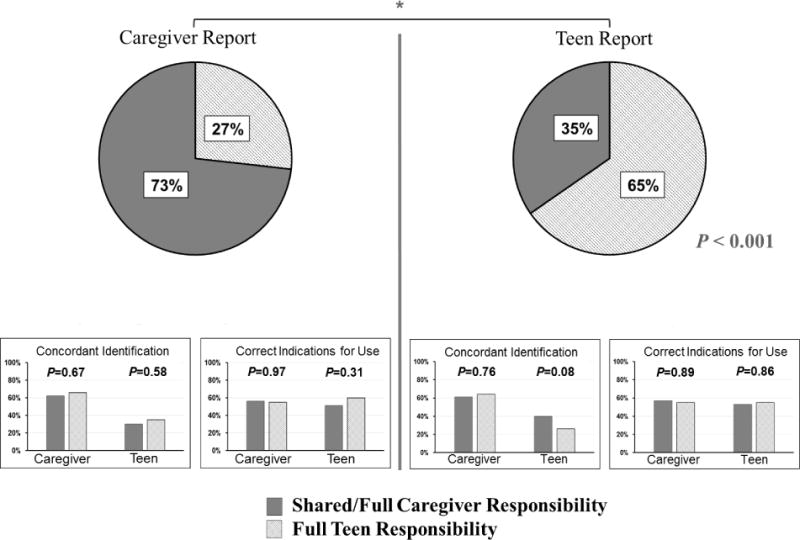

Responsibility for Medication Use: Rescue Medications

A smaller subject pool of 127 dyads was used for analyses of medication responsibility due to missing data for responsibility questions in the baseline survey. Importantly, no meaningful differences in baseline characteristics/demographics were identified in this group in comparison to the larger group of 136 dyads.

Caregivers were significantly less likely than teens to endorse that the teen was fully responsible for using rescue medication (27% vs. 65%, p < 0.001) (Figure 1a). We found no differences in either concordant identification or correct indications for use, for either caregivers or teens, based on caregiver reported responsibility for rescue medication use (Figure 1b). Analyses using teen report of responsibility similarly did not reveal any significant differences in caregiver or teen knowledge of inhaled medications based on level of responsibility (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Responsibility and Knowledge of Tnhaled Rescue Medications

Figure 1a. Responsibility for Rescue Medications

Figure 1b. Medication knowledge compared by caregiver report of responsibility

Figure 1c. Medication knowledge compared by teen report of responsibility

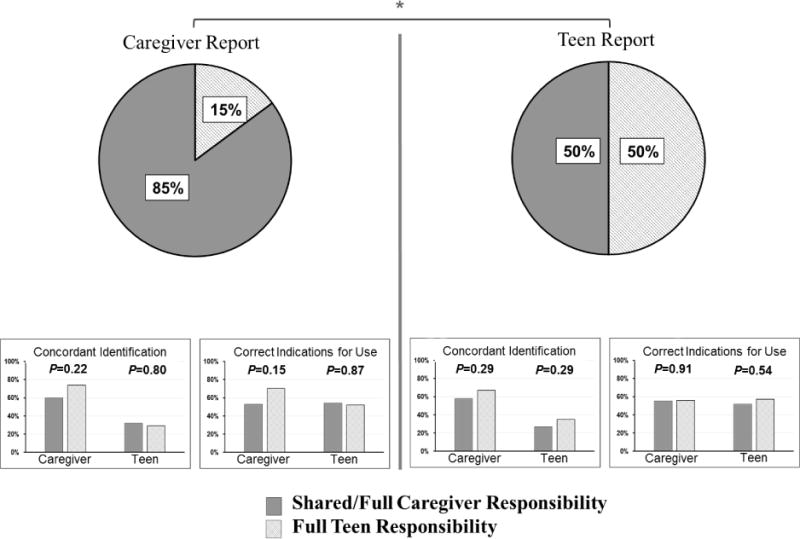

Responsibility for Medication Use: Controller Medications

Caregivers were less likely than teens to endorse “full teen responsibility” for controller medications use (15% vs. 50%, p < 0.001) (Figure 2a). We again used caregiver and teen report of responsibility in separate analyses to determine whether concordant identification or correct indications for use varied by level of teen responsibility. In both sets of analyses, “full teen responsibility” was not significantly associated with knowledge of inhaled medications among either caregivers or teens (Figures 2b and 2c).

Figure 2.

Responsibility and Knowledge of Inhaled Controller Medications

Figure 2a. Responsibility for Controller Medications

Figure 2b. Medication knowledge compared by caregiver report of responsibility

Figure 2c. Medication knowledge compared by teen report of responsibility

Responsibility for Medication Use: Sensitivity Analyses

All analyses detailed in the two sections above were repeated with reframed responsibility outcomes. When we compared “shared/full teen responsibility” with “full caregiver responsibility,” or left answers to responsibility questions ungrouped, no significant associations or trends between responsibility and either concordant identification or correct indications for use were identified (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Caregivers were better than teens at identifying inhaled asthma medications by providing names that matched selected pictures. Teens were more likely to identify medications by device color when asked to provide names. This observational finding adds to previous literature suggesting developmental differences in the way children identify asthma medications.(16, 17) There were no differences between caregivers and teens in their abilities to describe correct indications for medication use, and it is notable that more than 40% of all respondents (teen and caregiver alike) were unable to state correct indications for the very medications they identified.

While teens were more likely to endorse full personal responsibility for both rescue and controller medication use, “full teen responsibility” was not associated with identification or knowledge of correct indications for use. These findings indicate that medication knowledge is not a necessary precursor to teenage responsibility for medication use. It appears that many teens are assuming responsibility for medication self-management without understanding what the medications are or how they should be used. This represents a significant barrier to self-management in this population, and may be related to preventable morbidity.

Managing pediatric asthma during adolescence presents an evolving challenge for teens, caregivers, and providers. Adolescents gain responsibility for medication use as they get older, while caregiver responsibility diminishes.(1) Clinic-based asthma education(22–24) and self-management support(25) can improve pediatric asthma outcomes, particularly if children are involved.(25) While one study found that caregiver knowledge of asthma was associated with increased hospital readmissions, (26) knowledge about chronic disease is considered necessary (if not sufficient) for self-management behaviors among adolescents.(27) Knowledge about controller medications in particular has been linked with adherence among adolescents,(28) and adherence improves when adolescents are directly involved in medication planning.(29) Unfortunately, conversations about medications are typically directed at caregivers, with children and adolescents often largely excluded from vital management discussions.(14) Not engaging children and adolescents about asthma medications represents a missed opportunity for high quality asthma care, and opens to speculation the sources of information about asthma medications that teens use during this important transitional period.

Prior work on dyadic asthma management found that caregivers and children/teens often perform management tasks independently and are not influenced by each other’s asthma knowledge.(30) The present findings expand on this conclusion, with no observed association between medication knowledge and responsibility within dyads. It should be noted that caregivers are often excluded from clinical decisions about asthma management as well, (31) and important information about new prescriptions (e.g., medication names, indications for use) may not be conveyed by the provider.(32) Efforts to improve medication knowledge by involving pediatric patients and caregivers will need to ensure consistent delivery of high quality, patient-centered asthma education, and mastery of the content should be assessed at each visit.

Additional studies will be necessary to determine the clinical implications of our finding that teen knowledge of medications is not associated with responsibility. Caregiver difficulty in identifying inhaled asthma medications used by children (3–10 years) with persistent asthma is associated with a significantly greater symptom burden,(33) while caregiver misunderstanding about indications for controller medication use is associated with poor adherence.(34) It is unclear whether medication knowledge among teens or dyads is similarly associated with adherence or control. Any such work should incorporate responsibility for routine use: discrepancies in allocated responsibility for medication use have been associated with poor adherence in pediatric HIV,(18) while dyadic agreement on responsibility sharing has been associated with improved glycemic control in juvenile diabetes.(35) Future studies should explore whether dyadic knowledge of medications and responsibility sharing are associated with morbidity indicators (e.g., acute care utilization) among young teens with persistent asthma.

Our analyses are subject to several limitations. Findings from this one group of high-risk adolescents with uncontrolled persistent asthma may not be generalizable to all pediatric populations with asthma, including families from different economic or racial/ethnic backgrounds. The measures for concordant identification and correct indications for use have not been independently validated and should be tested further, with separate assessments of rescue and controller medication knowledge. Future work on medication knowledge may benefit from comparisons with prescription records and an assessment of respondent “accuracy,” with the caveat that accuracy assessments present separate challenges. Outpatient medication lists may include prescriptions no longer used by patients, exclude prescriptions started in acute care settings, and fail to capture pharmacy-level changes that accommodate insurance formulary requirements. These points are salient to our community-based sample that was enrolled regardless of contact with the healthcare system. Further, many prescriptions (including asthma medications) are never filled, limiting the practical knowledge of those medications among respondents. Pharmacy records could allow for a determination of filled prescriptions, but would not capture patient use of family medications. Accuracy comparisons may reflect provider expectations for management, however, and so merit future assessment.

The two measures of medication responsibility have also not been independently validated, although they were based on prior tools to assess responsibility for chronic illness care.(20, 21) Finally, there is a potential for social desirability bias among respondents when describing responsibility: both caregivers and teens might overestimate their personal degree of responsibility. While this may partially explain the lack of association between “full teen responsibility” and medication knowledge when reported by teenagers, social desirability bias would be less likely to explain the lack of association when “full teen responsibility” was reported by caregivers.

In summary, we found that many caregivers and teens with uncontrolled persistent asthma experienced difficulty with identifying inhaled medications and stating correct indications for use, regardless of which member of the dyad assumed primary responsibility for the medications. Healthcare providers who wait until the middle adolescent years before directly discussing asthma self-management with teens risk missing opportunities to engage with the key stakeholders to adherence. Targeting both members of the dyad with education and self-management strategies before responsibility transitions start will likely help empower teens with a stronger foundation for life-long disease management.

WHAT’S NEW.

Adolescents with persistent asthma develop increasing responsibility for medication use.(1) This study indicates that caregiver and teen knowledge about inhaled medications is suboptimal, and is not associated with the level of teen responsibility for medication use.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R18 HL116244). The funding source did not have a role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Orrell-Valente JK, Jarlsberg LG, Hill LG, Cabana MD. At what age do children start taking daily asthma medicines on their own? Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1186–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, Zahran HS, King M, Johnson CA, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;94:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Simon AE, Schoendorf KC. Trends in racial disparities for asthma outcomes among children 0 to 17 years, 2001–2010. J Allergy Clin Immun. 2014;134(3):547. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flores G, Snowden-Bridon C, Torres S, Perez R, Walter T, Brotanek J, et al. Urban minority children with asthma: substantial morbidity, compromised quality and access to specialists, and the importance of poverty and specialty care. J Asthma. 2009;46(4):392–8. doi: 10.1080/02770900802712971. Epub 2009/06/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oraka E, Iqbal S, Flanders WD, Brinker K, Garbe P. Racial and ethnic disparities in current asthma and emergency department visits: findings from the national health interview survey, 2001–2010. J Asthma. 2013;50(5):488–96. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2013.790417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams RJ, Fuhlbrigge A, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Livingston JM, Weiss KB, et al. Impact of inhaled antiinflammatory therapy on hospitalization and emergency department visits for children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4):706–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGrady ME, Hommel KA. Medication adherence and health care utilization in pediatric chronic illness: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):730–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Klein RB, Fritz GK. Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: reasoning, responsibility, and behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28(5):323–33. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabaté E, Organization WH . Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action. World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rand CS, Butz AM, Kolodner K, Huss K, Eggleston P, Malveaux F. Emergency department visits by urban African American children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105(1 Pt 1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desai M, Oppenheimer JJ. Medication adherence in the asthmatic child and adolescent. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2011;11(6):454–64. doi: 10.1007/s11882-011-0227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Academy of P, American Academy of Family P, American College of P, Transitions Clinical Report Authoring G. Cooley WC, Sagerman PJ. Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):182–200. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lotstein DS, Ghandour R, Cash A, McGuire E, Strickland B, Newacheck P. Planning for health care transitions: results from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e145–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cahill P, Papageorgiou A. Triadic communication in the primary care paediatric consultation: a reviw of the literature. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(544):904–11. doi: 10.3399/096016407782317892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bailey SC, Oramasionwu CU, Wolf MS. Rethinking adherence: a health literacy-informed model of medication self-management. J Health Commun. 2013;18(Suppl 1):20–30. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pradel FG, Hartzema AG, Bush PJ. Asthma self-management: the perspective of children. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(3):199–209. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Maria C, Lussier MT, Bajcar J. What do children know about medications? A review of the literature to guide clinical practice. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):291–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin S, Elliott-DeSorbo DK, Wolters PL, Toledo-Tamula MA, Roby G, Zeichner S, et al. Patient, caregiver and regimen characteristics associated with adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(1):61–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000250625.80340.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenahan JL, McCarthy DM, Davis TC, Curtis LM, Serper M, Wolf MS. A Drug by Any Other Name: Patients’ Ability to Identify Medication Regimens and Its Association With Adherence and Health Outcomes. Journal of Health Communication. 2013;18:31–9. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wade SL, Islam S, Holden G, Kruszon-Moran D, Mitchell H. Division of responsibility for asthma management tasks between caregivers and children in the inner city. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20(2):93–8. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199904000-00004. Epub 1999/04/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vesco AT, Anderson BJ, Laffel LMB, Dolan LM, Ingerski LM, Hood KK. Responsibility Sharing between Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes and Their Caregivers: Importance of Adolescent Perceptions on Diabetes Management and Control. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35(10):1168–77. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guevara JP, Wolf FM, Grum CM, Clark NM. Effects of educational interventions for self management of asthma in children and adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmj. 2003;326(7402):1308–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7402.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyd M, Lasserson TJ, McKean MC, Gibson PG, Ducharme FM, Haby M. Interventions for educating children who are at risk of asthma-related emergency department attendance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD001290. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001290.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark NM, Houle CR, Partridge MR. Educational Interventions to Improve Asthma Outcomes in Children. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2007;14(10):554–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirk S, Beatty S, Callery P, Gellatly J, Milnes L, Pryjmachuk S. The effectiveness of self-care support interventions for children and young people with long-term conditions: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39(3):305–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auger KA, Kahn RS, Davis MM, Simmons JM. Pediatric asthma readmission: asthma knowledge is not enough? J Pediatr. 2015;166(1):101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed-Knight B, Blount RL, Gilleland J. The transition of health care responsibility from parents to youth diagnosed with chronic illness: a developmental systems perspective. Fam Syst Health. 2014;32(2):219–34. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koster ES, Philbert D, Winters NA, Bouvy ML. Adolescents’ inhaled corticosteroid adherence: the importance of treatment perceptions and medication knowledge. J Asthma. 2015;52(4):431–6. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2014.979366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beresford BA, Sloper P. Chronically ill adolescents’ experiences of communicating with doctors: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(3):172–9. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Horner SD, Brown A. An exploration of parent-child dyadic asthma management influences on quality of life. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2015;38(2):85–104. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2015.1017668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sleath BL, Carpenter DM, Sayner R, Ayala GX, Williams D, Davis S, et al. Child and caregiver involvement and shared decision-making during asthma pediatric visits. J Asthma. 2011;48(10):1022–31. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.626482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarn DM, Heritage J, Paterniti DA, Hays RD, Kravitz RL, Wenger NS. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(17):1855–62. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frey SM, Fagnano M, Halterman J. Medication Identification Among Caregivers of Urban Children With Asthma. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(8):799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farber HJ, Capra AM, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Quesenberry CP, Jensvold NG, et al. Misunderstanding of asthma controller medications: association with nonadherence. J Asthma. 2003;40(1):17–25. doi: 10.1081/jas-120017203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson BJ, Holmbeck G, Iannotti RJ, McKay SV, Lochrie A, Volkening LK, et al. Dyadic measures of the parent-child relationship during the transition to adolescence and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Fam Syst Health. 2009;27(2):141–52. doi: 10.1037/a0015759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]