Abstract

Background

Maternal prenatal supplementation with folic acid and other vitamins has been inconsistently associated with a reduced risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Little is known regarding the association with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a rarer subtype.

Methods

We obtained original data on prenatal use of folic acid and vitamins from 12 case-control studies participating in the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium (enrollment period: 1980-2012), including 6,963 cases of ALL, 585 cases of AML, and 11,635 controls. Logistic regression was used to estimate pooled odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI), adjusted for child's age, sex, ethnicity, parental education, and study center.

Results

Maternal supplements taken any time preconception and/or during pregnancy were associated with a reduced risk of childhood ALL; ORs for vitamin and folic acid use were 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78-0.92) and 0.80 (95% CI: 0.71-0.89) respectively. The reduced risk was more pronounced in children whose parents' education was below tertiary level. The analyses for AML led to somewhat unstable estimates; ORs= 0.92 (95% CI: 0.75-1.14) and 0.68 (95% CI: 0.48-0.96) for prenatal vitamins and folic acid, respectively. There was no strong evidence that risks of ALL or AML varied by period of supplementation (preconception, pregnancy, or trimester).

Conclusions

Our results, based on the largest number of childhood leukemia cases to date, suggest that maternal prenatal use of vitamins and folic acid reduces the risk of ALL and AML, and that the observed association with ALL varies by parental education, a surrogate for lifestyle and socio-demographic characteristics.

Introduction

Acute leukemias are the most common cancers in children under 15 years of age; 80% are acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 17% acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and 3% chronic myeloid leukemia.1,2 The incidence of ALL peaks in children 2-5 years old, while the incidence of AML is constant across ages.1,2 The early onset of leukemia is suggestive of genetic predisposition and critical exposures occurring before and during pregnancy. Prenatal supplementation with folic acid and other vitamins, known to maintain DNA integrity 3 and reduce oxidative stress 4,5 could play a role in the prevention of childhood leukemia. The risk of childhood ALL following maternal folic acid or vitamin intake before and during pregnancy has been studied before but results have been inconsistent.6-17 This may be due to different underlying genetic susceptibilities in the studied populations, temporal variations in folic acid and vitamin intake over study periods, but also to limited statistical power of individual studies. Meta-analyses of published results reported a non-statistically significant reduced risk of ALL associated with maternal use of vitamins during pregnancy, but not before conception.7,8,10 Little is known about the risk of AML in relation to maternal supplementation with folic acid or vitamins6-17

To overcome the limitations of previous studies, we pooled original data on prenatal intake of folic acid and vitamins from 12 case-control studies participating in the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium (CLIC) 18, and examined the associations with childhood ALL (overall and by immunophenotype) and AML. We also evaluated the modifying effects of education level as a marker of nutritional status 19-23, and of alcohol consumption, which is known to modify folate metabolism.24

Methods

Study Population

Twelve case-control studies conducted in 10 countries from 1980 to 2012 and participating in CLIC (clic.berkeley.edu) 18 contributed data to the current pooled analyses (Table 1); this included eight studies with published data from Australia,10 Canada,14 France,6 Germany,13 New Zealand,7 and the United States,9,16,17 and four studies from Brazil, Costa Rica, Egypt, and Greece with unpublished data at the time of this report. Study design and characteristics of participants in individual studies have been described previously.18 A total of 19,183 children were available for analysis (6,963 cases of ALL, 585 cases of AML, and 11,635 controls). Information on immunophenotype was available for 84% of ALL, including 5,193 children diagnosed with precursor B-cell ALL and 678 with T-cell ALL.

Table 1. Study Characteristics and Data Availability for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, and Controls.

| Data Availability | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Study Characteristics | Vitamin Use | Folic Acid Use | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| Studies | Enrollment Period | Year of Folic Acid Recommendation | No. controls | No. Cases | Total No. | Any Timea | Preconceptionb | Pregnancy | Any Timea | Preconceptionb | Pregnancy | |

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| ALL | AML | % | % | % | % | % | % | |||||

| Canada14 | 1980–2000 | 1998 | 790 | 790 | — | 1580 | 99 | 87 | 97 | 88 | 87 | 87 |

| US CCG16 | 1989–1993 | 1992 | 1986 | 1842 | — | 3828 | 99 | 100 | 100 | — | — | — |

| New Zealand7 | 1989–1994 | 1995 | 303 | 97 | 22 | 422 | 96 | 95 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| Germany13 | 1992–1997 | 1995 | 2458 | 751 | 130 | 3339 | 98 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Costa Rica | 1995–2000 | 1998 | 579 | 251 | 33 | 863 | 98 | — | 98 | 97 | — | 97 |

| US NCCLS9,17 | 1995–2002 | 1992 | 492 | 406 | 74 | 972 | 97 | 97 | — | 99 | 99 | — |

| Brazil | 1999–2002 | 2002 | 413 | 141 | 47 | 601 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 98 |

| Greece | 1996–2011 | n/a | 1026 | 920 | 108 | 2054 | 100 | — | 100 | — | — | — |

| France6 | 2003–2005 | 2004 | 1681 | 647 | 100 | 2428 | 97 | 93 | 95 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| Australia10,15 | 2003–2006 | 1992 | 822 | 385 | — | 1207 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| US NCCLS9,17 | 2003–2008 | 1992 | 734 | 434 | 71 | 1239 | 99 | 97 | 98 | 97 | 98 | 98 |

| Egypt | 2009–2012 | 1997 | 351 | 299 | — | 650 | 98 | — | 98 | — | — | — |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total no. studies | 12 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Total no. subjects | 11635 | 6963 | 585 | 19183 | 18873 | 11794 | 14625 | 8921 | 8070 | 7943 | ||

| B-cell | 5193 | 5117 | 3289 | 4083 | 2192 | 2184 | 1817 | |||||

| T-cell | 678 | 658 | 481 | 561 | 322 | 320 | 287 | |||||

| Not specified | 1092 | 1070 | 796 | 1060 | 488 | 252 | 485 | |||||

ALL indicates acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia; AML, Acute Myeloid Leukemia; CCG, Children's Cancer Group; NCCLS, Northern California Childhood Leukemia Study

Any time is defined as any point before or during pregnancy

Preconception is defined by studies as between 3 months to 1 year before conception, or time is not specified

Data Collection and Standardization

The participating CLIC studies provided original data on self-reported maternal supplementation with folic acid and other vitamins up to one year before conception and during pregnancy. Information on the type and period of supplementation included (i) the use of dietary supplements, which may have contained folic acid or not, (ii) the use of specific vitamins such as folic acid, vitamin C, vitamin D, or others (iii) the supplementation taken at any time during the prenatal period (whether or not information on the periods of use preconception and/or during pregnancy was specified, referred to as “any time” in the text), and (iv) the supplementation taken in a specific time period (preconception or during pregnancy as a whole or by trimester).We also obtained data on leukemia subtypes, the child's race/ethnicity, gender, and age (at diagnosis for cases and corresponding age for controls participating in age-matched studies or age at enrollment/interview), birth weight, mother's age at delivery, maternal and paternal education level, and maternal alcohol consumption. The availability of data on maternal supplement use by type and period, for each participating study and overall is summarized in Table 1. Twelve studies provided data on vitamin supplementation any time before or during pregnancy (98% complete), whereas seven studies provided data specific to supplementation with folic acid during pregnancy, representing data for 47% of all study subjects (Table 1).

Data were checked in collaboration with the principal investigators of each study and were standardized across studies for the pooled analyses. In particular, the standardized variable for use of any vitamins included women who reported single or multivitamins that did or did not contain folic acid; the use of mineral supplements such as iron was not taken into consideration. Women who specifically reported taking folic acid were included in the group “folic acid”.Time-specific variables were created for maternal supplementation with any vitamins any time prenatally, preconception, during pregnancy, and by trimesters. Identical time-specific variables were created for maternal intake of folic acid. Other variables with heterogeneous definitions across studies were classified into the following categories for ethnicity (White/Caucasian/European vs. other) and highest level of parental (father or mother) education (none or primary, secondary, and tertiary, generally meaning some university education). For each study, we obtained the approximate year when food fortification with folic acid was recommended and/or implemented. Information was either publicly available or provided by the investigators of the participating studies. Based on the year of birth, we assigned for each child a value for being born before or after folic acid fortification.

Statistical Analyses

Study-specific and pooled odds ratios (ORs) as well as approximate 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated from unconditional logistic regression models, separately for ALL and AML, and by immunophenotype for ALL (B- and T-cell lineage). All variables, except mother's age at delivery, child's age at diagnosis (and corresponding age for controls) and birth weight, were categorical. Models were adjusted for child's age, sex, ethnicity, and parental education level as these variables were either matching factors in the individual matched studies or treated as confounders. We present models without and with adjustment for study center (Models 1 and 2, respectively) for the main analyses on use of vitamin/folic acid supplements any time, preconception and during pregnancy; only study-adjusted models (Model 2) are presented for additional analyses. Overall, adjusting for study center improved the fit of all models (p-values for log-likelihood ratio test [LRT] < 0.001). Other variables (child's birth weight, maternal age at delivery, maternal alcohol intake, and child born before/after folic acid food fortification) were not included in the final models as the ORs changed by less than 10%.We conducted stratified analyses by sex, age at diagnosis (infants 0-1 year old vs. older children), parental education (none/primary, secondary, and tertiary), maternal alcohol consumption (drinkers vs. non-drinkers), and folic acid food fortification (child born before vs. after). P-values for heterogeneity between strata were obtained from the LRT or Woolf's test.

In order to characterize the heterogeneity in vitamin and folic acid supplementation between participating CLIC studies and account for it in the analysis, we assessed the contribution of the between-study variability and within-study variability into the total variability. Total variability Np(1-p) was partitioned into between-study variability (which represents the deviation of study-specific prevalence from the mean prevalence for all studies combined, weighted by the number of subjects in individual studies, VB=Σni(pi-p)2)and within-study variability (which represents the deviation of individual subjects from the study- specific mean prevalence, weighted by the number of subjects in their corresponding study (VW=Σnipi (1-pi)), where N is the total number of cases and controls across all studies, n is the total number of subjects in each study, p is the proportion of women taking vitamins across all studies, and pi is the proportion of women taking vitamins in each study. For use of vitamin and folic acid any time and during pregnancy, VB accounted for approximately 33% to 44% of the total variability, whereas for preconception vitamin and folic acid intake VB accounted for about 16% of the total variability. Subsequently, we grouped the study sites into those contributing to either the lowest between-study variability (VB<30% of total variability) or the highest between-study variability (VB≥ 30% of total variability), and conducted stratified analyses for each group to assess the impact of study heterogeneity in Models 1 versus 2. The cut point for grouping studies with low versus high VB was driven by the data. Lastly, we conducted sensitivity analyses by systematically excluding two studies (out of 12) at a time, which resulted in 66 sets of 10 studies. For each set, we then computed the ORs and 95% CI for each type and period of maternal supplementation. Out of a total of 66 ORs, we calculated the minimum, mean and maximum OR, and the corresponding 95% CIs.

Results

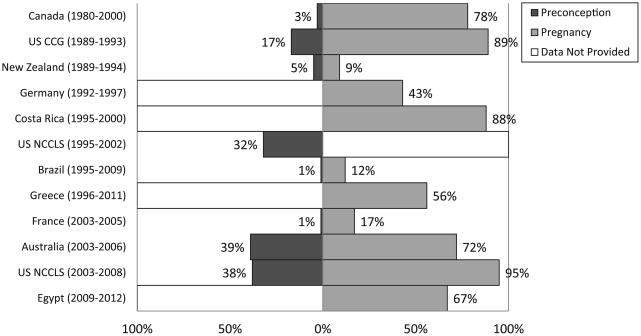

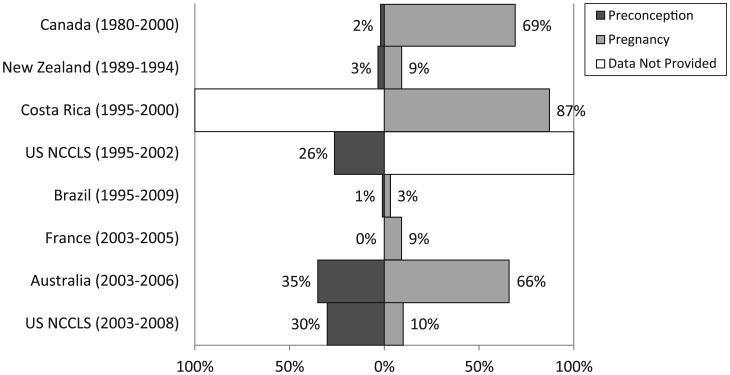

The distribution of socio-demographic characteristics among cases and controls in the pooled dataset is shown in Table 2. The percentages of mothers reporting vitamin supplementation before and during pregnancy varied considerably by country and by study period (Figure 1). Between 1% and 39% of mothers reported taking vitamins before pregnancy, while use during pregnancy ranged from 9% to 95% vitamin use during pregnancy was most common in North America, Costa Rica and Australia, and least common in Brazil, France, Germany and New Zealand. Between-study differences were also observed for maternal intake of folic acid in the subset of studies where this information was available (Figure 2). The Pearson correlation coefficients between maternal supplementation before conception and during pregnancy were 0.28 for vitamins and 0.23 for folate (p<0.001).

Table 2. Sociodemographic Characteristics for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cases, Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cases, and Controls: Childhood Leukemia International Consortium.

| Cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| ALL (n=6963 No. (%) | AML (n=585) No. (%) | Controls (n=11635) No. (%) | |

| Child's age (year)a | |||

| 0–1 | 871 (13) | 204 (35) | 2036 (17) |

| 2–5 | 3782 (54) | 122 (21) | 5068 (44) |

| 6–10 | 1582 (22) | 148 (25) | 2853 (25) |

| 11–14 | 728 (11) | 111 (19) | 1678 (14) |

| Child's sex | |||

| Male | 3932 (56) | 316 (54) | 6457 (55) |

| Female | 5178 (44) | 269 (46) | 5178 (45) |

| Child's ethnicity | |||

| White/European/Caucasian | 5565 (80) | 453 (77) | 9719 (84) |

| Other | 1389 (20) | 127 (22) | 1875 (16) |

| Missing | 9 (0) | 5 (1) | 41 (0) |

| Parental educationbb | |||

| None/Primary | 1049 (15) | 147 (25) | 2145 (18) |

| Secondary | 2826 (41) | 188 (32) | 4174 (36) |

| Terrtiary | 3043 (44) | 236 (40) | 5190 (45) |

| Missing | 45 (1) | 14 (2) | 126 (1) |

| Birth weight (grams) | |||

| <2499 | 373 (5) | 28 (5) | 676 (6) |

| 2500–3999 | 5475 (79) | 471 (81) | 9363 (80) |

| >4000 | 881 (13) | 71 (12) | 1256 (11) |

| Missing | 234 (3) | 15 (3) | 340 (3) |

| Mother's age at delivery (years) | |||

| <26 | 2488 (36) | 217 (37) | 3735 (32) |

| 26–30 | 2328 (33) | 182 (31) | 4249 (37) |

| 31–35 | 1558 (22) | 129 (22) | 2605 (22) |

| 36–40 | 502 (7) | 41 (7) | 871 (7) |

| >40 | 79 (1) | 14 (2) | 163 (1) |

| Missing | 9 (1) | 2 (0) | 12 (0) |

Child's age defined as recruitment/interview for controls, and diagnosis for cases

Parental education defined as highest education level between the mother and father

Figure 1.

Maternal vitamin supplementation preconception and during pregnancy, by study. For data from Germany, data for vitamin use were collected for preconception and/or pregnancy period. CCG indicates Children's Cancer Group; NCCLS, Northern California Childhood Leukemia Study.

Figure 2.

Maternal folic acid supplementation preconception and during pregnancy, by study. NCCLS indicates Northern California Childhood Leukemia Study.

Childhood ALL

The adjusted study-specific ORs for risk of ALL associated with maternal intake of vitamins any time prenatally ranged from 0.44 (95% CI: 0.26-0.77) in Costa-Rica to 1.18 (95% CI: 0.65-2.14) in Brazil (Table 3). The study-specific ORs for vitamin supplementation preconception and during pregnancy also varied across studies (eTable 1, http://links.lww.com/EDE/A806).

Table 3. Risk of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia and Acute Myeloid Leukemia Associated with Maternal Vitamin Supplementation Any Time Preconception or During Pregnancy, by Study.

| No. Exposed | OR (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Studies | Total No. | Controls | ALL | AML | ALL | AML |

| Canada | 1580 | 622 | 608 | — | 0.89 (0.70–1.13) | — |

| US CCG | 3828 | 1827 | 1622 | — | 0.73 (0.59–0.91) | — |

| New Zealand | 422 | 29 | 8 | 0 | 0.97 (0.42–2.23) | — |

| Germany | 3339 | 1046 | 290 | 53 | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | 1.00 (0.69–1.47) |

| Costa Rica | 863 | 508 | 203 | 23 | 0.44 (0.26–0.77) | 0.26 (0.09–0.79) |

| US NCCLS (1995–2002) | 972 | 155 | 127 | 22 | 1.08 (0.80–1.47) | 1.10 (0.61–1.97) |

| Brazil | 601 | 46 | 21 | 5 | 1.18 (0.65–2.14) | 1.11 (0.39–3.11) |

| Greece | 2054 | 586 | 494 | 65 | 0.87 (0.72–1.04) | 1.13 (0.75–1.70) |

| France | 2428 | 331 | 89 | 14 | 0.65 (0.50–0.84) | 0.72 (0.40–1.29) |

| Australia | 1207 | 612 | 279 | — | 1.03 (0.77–1.37) | — |

| US NCCLS (2003–2008) | 1239 | 689 | 409 | 63 | 1.02 (0.58–1.79) | 0.73 (0.27–1.99) |

| Egypt | 650 | 228 | 198 | — | 0.87 (0.61–1.24) | — |

Study-specific results adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, and parental education

Table 4 shows the results of the pooled analyses for type and period of maternal supplementation for ALL. The ORs for maternal intake of vitamins and folic acid any time prenatally, with no adjustment for study center, were 1.21 (95% CI: 1.13-1.28) and 1.09 (95% CI: 0.99-1.19), respectively (Table 4, Models 1). In contrast, the analyses with adjustment for study center showed that maternal intake of vitamins and folic acid at any time was associated with a reduced risk of ALL in the offspring, with pooled ORs of 0.85 (95% CI: 0.78-0.92) and0.80 (95% CI: 0.71-0.89), respectively (Table 4, Models 2). There was no evidence that the magnitude of the association between prenatal vitamin and folic acid supplementation and ALL varied by period of use, i.e., preconception and pregnancy (Table 4), or by trimester (Table 5). The impact of adjustment for study on the pooled ORs for supplementation at any time and during pregnancy was stronger in the group of studies contributing to high between-study variability compared with those contributing to low between-study variability. Sensitivity analyses removing two studies at a time showed that the minimum, mean, and maximum study- adjusted ORs for ALL remained below one for each type and period of supplementation (eFigure 1). The findings for vitamins use and risk of childhood ALL using data from the 7 studies with folic acid data were very similar to those using the full set of 12 studies presented in Table 4 (data not shown).

Table 4. Risk of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Associated with Maternal Vitamin and Folic Acid Supplementation, Stratified by Study with Low or High Between-Study Variabilitya.

| Supplement, Period |

Data Availability | All Studies | Low Between-study Variabilityb | High Between-study Variabilityc | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| No. Controls |

No. Cases |

Model 1d | Model 2e | No. Controls |

No. Cases |

Model 1d | Model 2e | No. Controls |

No. Cases |

Model 1d | Model 2e | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| No. Studies |

No. Controls |

No. Cases |

OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |||||||

| Vitamins | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any time | 12 | 11466 | 6845 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 4787 | 2497 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1312 | 1108 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3475 | 1389 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 6679 | 4348 | 1.21 | (1.13–1.28) | 0.85 | (0.78–0.92) | 2711 | 1909 | 0.84 | (0.76–0.93) | 0.89 | (0.80–0.99) | 3968 | 2439 | 1.46 | (1.34–1.59) | 0.80 | (0.71–0.90) | |||

| Preconception | 8 | 6931 | 4566 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 5749 | 3834 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 1182 | 732 | 0.93 | (0.84–1.03) | 0.88 | (0.79–0.99) | |||||||||||||||

| Pregnancy | 10 | 8554 | 5704 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 3161 | 1844 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1051 | 873 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2110 | 971 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 5393 | 3860 | 1.17 | (1.09–1.26) | 0.81 | (0.74–0.88) | 3200 | 2160 | 0.79 | (0.71–0.88) | 0.88 | (0.78–0.98) | 2193 | 1700 | 1.57 | (1.41–1.74) | 0.68 | (0.58–0.80) | |||

| Folic acid | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any time | 8 | 5588 | 3002 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 3416 | 1769 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1460 | 794 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1956 | 975 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 2172 | 1233 | 1.09 | (0.99–1.19) | 0.80 | (0.71–0.89) | 439 | 261 | 1.08 | (0.90–1.30) | 0.92 | (0.76–1.12) | 1733 | 972 | 1.06 | (0.95–1.19) | 0.72 | (0.62–0.84) | |||

| Preconception | 7 | 5011 | 2756 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 4313 | 2404 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 698 | 352 | 0.89 | (0.77–1.02) | 0.82 | (0.70–0.96) | |||||||||||||||

| Pregnancy | 7 | 5094 | 2589 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 3294 | 1585 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1317 | 597 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1977 | 988 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 1800 | 1004 | 1.13 | (1.02–1.25) | 0.77 | (0.67–0.88) | 106 | 57 | 1.15 | (0.82–1.62) | 1.10 | (0.78–1.55) | 1694 | 947 | 1.06 | (0.94–1.18) | 0.72 | (0.62–0.83) | |||

Studies were separated into low- and high-high-variability groups, based on proportions of women taking vitamins or folic acid across each of the studies, when between-study variability contributed to more than 30% of the overall variability. Based on this criteria, studies were not stratified for the preconception time period.

Low-variability studies: Vitamins, any time: canada, Costa Rica, US NCCLS (1995–2002), greece, australia, egypt; Vitamins, pregnancy: canada, Costa Rica, Greece, Australia, US NCCLS (2003–2008), egypt; Folic acid, pregnancy: New Zealand, Brazil, US NCCLS (2003–2008)

High-variability studies: Vitamins, any time: US CCG, New Zealand, Germany, Brazil, France, US NCCLS (2003–2008); Vitamins, pregnancy: US CCG, New Zealand, Brazil, France; Folic acid, any time: Canada, Costa Rica, France, Australia; Folic acid, pregnancy: Canada, Costa Rica, France, Australia

Pooled OR adjusted adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, and parental education

Pooled OR adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, parental education, and study

Refererence category

Table 5. Risk of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Associated with Use of Vitamin and Folic Acid Supplementation Before and by Trimester During Pregnancy: Subsets of Childhood Leukemia International Consortium Studies.

| Use Before and During Pregnancy | Vitamins (7 Studies)a | Folic Acid (5 Studies)b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| No. Controls (n=6098) | No. Cases (n=4020) | OR | (95% CI)c | No. Controls (n=3608) | No. Cases(n=1898) | OR | (95% CI)c | |

| Nod | 2235 | 1183 | 1.00 | 2326 | 1096 | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 3863 | 2837 | 0.78 | (0.69–0.88) | 1282 | 802 | 0.78 | (0.67–0.91) |

| Preconception only | 41 | 29 | 0.85 | (0.51–1.39) | 21 | 12 | 1.05 | (0.51–2.18) |

| Trimester 1e | 288 | 151 | 0.79 | (0.63–0.99) | 268 | 132 | 0.80 | (0.63–1.03) |

| Trimester 2/3e | 445 | 330 | 0.86 | (0.72–1.03) | 270 | 145 | 0.66 | (0.52–0.84) |

| Trimester 1/2/3e | 3089 | 2327 | 0.75 | (0.66–0.85) | 723 | 513 | 0.82 | (0.69–0.98) |

Studies include: Australia, Brazil, Canada, Egypt, France, US CCG, US NCCLS (2003–2008)

Studies include: Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, US NCCLS (2003–2008)

Pooled OR adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, parental education, and study

Reference category

May or may not include preconception use

The magnitude of the associations with vitamin and folic acid intake was similar for B- and T-cell precursor ALL (Table 6). The reduction in ALL risk associated with folic acid intake any time prenatally was stronger for children whose parents had no formal or primary education (OR=0.47, 95% CI: 0.33-0.68), compared to those with secondary education (OR=0.73, 95% CI: 0.59-0.90) and tertiary education (OR=0.96, 95% CI: 0.82-1.12; p-value for interaction =0.01) (Table 6). A similar trend across education levels was observed for vitamin intake (p-value for interaction 0.14). Also, a reduction in risk was somewhat stronger for children whose mothers reported not drinking alcohol compared to those drinking alcohol; the 95% CIs, however, overlapped between strata (Table 6). Mothers drinking alcohol were more likely to have tertiary education (54%), than none/primary (12%) or secondary (34%) education (results not shown).

Table 6. Risk Of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Associated With Maternal Vitamin And Folic Acid Supplementation Any Time Before Or During Pregnancy: Stratified Analyses In Subsets Of Childhood Leukemia International Consortium Studies.

| Vitamins (Any Time) | Folic Acid (Any Time) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| No. Studies | No. Exposed | OR | (95% CI)a | Test for Interaction | No. Studies | No. Exposed | OR | (95% CI)a | Test for Interaction | |||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases | |||||||||

| Immunophenotype | ||||||||||||

| Overallb | 10 | 6125 | 3585 | 0.87 | (0.80–0.94) | 6 | 1661 | 1001 | 0.86 | (0.76–0.97) | ||

| B-cell | 10 | 6125 | 3222 | 0.87 | (0.80–0.95) | P = 0.45c | 6 | 1661 | 905 | 0.86 | (0.75–0.97) | P = 0.59c |

| T-cell | 9 | 5897 | 363 | 0.81 | (0.65–0.99) | 6 | 1661 | 96 | 0.84 | (0.62–1.14) | ||

| Maternal consumption of alcohol (any time) | ||||||||||||

| Overallb | 12 | 5989 | 3742 | 0.83 | (0.76–0.91) | 8 | 2168 | 1232 | 0.80 | (0.71–0.90) | ||

| No | 12 | 3274 | 2133 | 0.79 | (0.71–0.89) | P = 0.66d | 8 | 1059 | 595 | 0.75 | (0.64–0.90) | P = 0.14d |

| Yes | 12 | 2715 | 1609 | 0.89 | (0.78–1.01) | 8 | 1109 | 637 | 0.87 | (0.74–1.02) | ||

| Parental educatione | ||||||||||||

| Overallb | 12 | 6640 | 4336 | 0.85 | (0.78–0.92) | 8 | 2164 | 1228 | 0.80 | (0.71–0.89) | ||

| None/Primary | 12 | 873 | 447 | 0.72 | (0.60–0.88) | P = 0.14d | 8 | 352 | 132 | 0.47 | (0.33–0.68) | P = 0.01d |

| Secondary | 12 | 2649 | 1879 | 0.78 | (0.68–0.88) | 8 | 660 | 410 | 0.73 | (0.59–0.90) | ||

| Tertiary | 12 | 3118 | 2010 | 0.97 | (0.86–1.09) | 8 | 1152 | 686 | 0.96 | (0.82–1.12) | ||

| Child born before/after fortification | ||||||||||||

| Overallb | 12 | 6679 | 4348 | 0.85 | (0.78–0.92) | 8 | 2172 | 1233 | 0.80 | (0.71–0.89) | ||

| Before fortification | 12 | 6046 | 3971 | 0.86 | (0.79–0.93) | P = 0.15d | 8 | 1892 | 1075 | 0.78 | (0.69–0.89) | P = 0.96d |

| After fortification | 12 | 633 | 377 | 0.66 | (0.45–0.97) | 8 | 280 | 158 | 0.84 | (0.64–1.11) | ||

Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, parental education, and study. Or for parental education is adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, and study

Overall OR is given on the entire subset for which data are available for a specific stratified analysis

Woolf test

Log ratio test

Parental education defined as the highest education level between the mother and father

Stratified analyses for children born before or after folic acid food fortification did not reveal substantial differences in ORs (all 95% CIs overlapped) (Table 6). All stratified analyses were also conducted separately for supplement use preconception and during pregnancy (eTable 2, http://links.lww.com/EDE/A806). The results were similar for the period of the pregnancy while those for the preconception period were less consistent; for example, there was a tendency for lower risk estimates associated with vitamin and folate supplementation for children born after folic acid food fortification (eTable 2).The reductions in risk following folate acid supplementation appeared stronger in infants and boys, although these observations were consistent with chance variation (data not shown).

Childhood AML

The study-specific ORs estimating the risk of childhood AML associated with maternal intake of vitamins any time ranged from 0.26 (95% CI: 0.09-0.79) in Costa Rica to 1.13 (95% CI: 0.75-1.70) in Brazil (Table 3). The study-specific ORs associated with supplementation preconception and during pregnancy also varied across studies (eTable 3).

Table 7 shows the results of the pooled analyses for type and period of maternal supplementation, without and with adjustment for study center (Models 1 and Models 2, respectively). Just as in the analyses for ALL, the impact of adjustment for study center on the pooled ORs for AML was stronger in the group of studies with high between-study variability compared with those with low between-study variability. The study-adjusted pooled ORs associated with vitamin and folic acid supplementation at any time were 0.92 (95% CI: 0.75- 1.14) and 0.68 (95% CI: 0.48-0.96), respectively (Table 7, Models 2). The reduction in risk appeared stronger for maternal intake of folic acid during pregnancy (OR=0.52; 95% CI: 0.31- 0.89) vs. preconception (OR=0.88; 95% CI: 0.59-1.32), although the 95% CI intervals overlapped; there was no evidence that the risk of AML associated with vitamin intake varied by period of use (Table 7, Models 2). Sensitivity analyses for supplementation with folic acid showed that the mean ORs for AML remained below one; however, maximum ORs and most upper limits of the 95% CIs were above one, indicating that the results may be unstable (eFigure 2). Also, the ORsmodel 2 using data from the 7 studies with folic acid data were 0.74 (95% CI (0.53-1.05) and 0.65 (95% CI (0.43, 1.00) for vitamin use anytime and during pregnancy, respectively (not shown in tables); these were lower than the ORs from the analysis using the full set of 12 studies (Table 7). Note that the same 7 studies provided data for vitamins and folate preconception. The sample size was insufficient for meaningful stratified analyses.

Table 7. Risk of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Associated with Maternal Vitamin and Folic Acid Supplementation, Stratified by Study with Low or High Between-Study Variabilitya.

| Supplement, Period |

All Studies | Low Between-study Variabilityb | High Between-study Variabilityc | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Data Availability | No. Controls |

No. Cases |

Model 1d | Model 2e | No. Controls |

No. Cases |

Model 1d | Model 2e | No. Controls |

No. Cases |

Model 1d | Model 2e | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| No. Studies |

No. Controls |

No. Cases |

OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |||||||

| Vitamins | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any time | 8 | 7534 | 562 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nof | 4144 | 317 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2448 | 192 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1696 | 125 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 3390 | 245 | 0.95 | (0.80–1.14) | 0.92 | (0.75–1.14) | 2324 | 163 | 1.01 | (0.80–1.26) | 1.00 | (0.79–1.28) | 1066 | 82 | 1.06 | (0.77–1.46) | 0.75 | (0.47–1.18) | |||

| Preconception | 5 | 3448 | 297 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 2959 | 247 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 489 | 50 | 1.28 | (0.92–1.79) | 0.96 | (0.66–1.39) | |||||||||||||||

| Pregnancy | 6 | 4638 | 367 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 2477 | 198 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 811 | 78 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1666 | 120 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 2161 | 169 | 1.02 | (0.82–1.26) | 0.85 | (0.64–1.14) | 1804 | 151 | 0.84 | (0.63–1.13) | 0.88 | (0.63–1.25) | 357 | 18 | 0.69 | (0.41–1.16) | 0.75 | (0.44–1.25) | |||

| Folic acid | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any time | 6 | 4078 | 331 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 2964 | 264 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1460 | 167 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1504 | 97 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 1114 | 67 | 0.73 | (0.55–0.97) | 0.68 | (0.48–0.96) | 439 | 41 | 0.86 | (0.59–1.26) | 0.86 | (0.58–1.27) | 675 | 26 | 0.67 | (0.42–1.07) | 0.35 | (0.18–0.68) | |||

| Preconception | 5 | 3510 | 303 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 3131 | 266 | 1.00 | 1.00 | — | — | — | — | |||||||||||||

| Yes | 379 | 37 | 1.19 | (0.82–1.73) | 0.88 | (0.59–1.32) | |||||||||||||||

| Pregnancy | 5 | 3593 | 260 | ||||||||||||||||||

| nof | 2825 | 226 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1317 | 129 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1508 | 97 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Yes | 768 | 34 | 0.61 | (0.41–0.90) | 0.52 | (0.31–0.89) | 106 | 8 | 0.81 | (0.38–1.71) | 0.85 | (0.40–1.80) | 662 | 26 | 0.67 | (0.42–1.08) | 0.36 | (0.18–0.71) | |||

Studies were separated into low- and high-variability groups, based on proportions of women taking vitamins or folic acid across each of the studies, when between-study variability contributed to more than 30% of the overall variability. Based on this criteria, studies were not stratified for the preconception time period.

Low-variability studies: Vitamins, any time: canada, Costa Rica, US NCCLS (1995–2002), greece, australia, egypt; Vitamins, pregnancy: canada, Costa Rica, Greece, Australia, US NCCLS (2003–2008), egypt; Folic acid, pregnancy: New Zealand, Brazil, US NCCLS (2003–2008)

High-variability studies: Vitamins, any time: Brazil, France, US NCLS (2003–2008); Vitamins, pregnancy: Brazil, France; Folic acid, any time: Costa Rica, France; Folic acid, pregnancy: Costa Rica, France

Pooled OR adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, and parental education

Pooled OR adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, parental education, and study

Refererence category

Discussion

Although acute leukemia is the most common cancer in children, it is a relatively rare disease, therefore bringing challenges to the investigation of possible risk factors. This large international collaborative CLIC study, which includes over 7,000 children diagnosed with acute leukemia and 11,000 controls, found moderate reductions in risk of ALL following maternal intake of vitamin and folic acid supplements before or during pregnancy. Similarly, a reduced risk of AML was observed with folic acid use before or during pregnancy, whereas results for vitamins were inconclusive. There was no strong evidence that the risks of ALL and AML varied by period of supplementation (preconception, pregnancy, and trimester). Stratified analyses revealed possible differences in risk by parental education, a crude indicator of dietary quality.

Previous individual case-control studies have reported inverse 6,15 or null 7,10,14 associations between maternal folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and childhood ALL, as well as inverse,6,7,13,16 null,10,14 or positive 11 associations with any or multi-vitamins. Regarding supplementation during the preconception period, reduced risks have been associated with folic acid,9,10 while results were inconsistent for any vitamins or multi-vitamin intake.9-12,16 These studies were generally limited by small number of leukemia cases. Also, some of them were conducted in affluent populations with high intakes of folate from dietary and supplemental sources, leading to low exposure variation and limited power to uncover the alternative hypothesis. Three meta-analyses including small numbers of published studies (two to five) on childhood ALL suggested a protective effect for prenatal vitamins,8,10 but not for folic acid.7,10 As for childhood AML, only a few studies have been conducted to date: null results or moderately decreased risks were reported for maternal supplementation with vitamins ‘before and during pregnancy,6,11,13 and with folic acid use.6

To address the limitations of previous studies on childhood acute leukemias, we pooled original data from eight published series from Northern America, Europe, and Oceania 6,7,9,10,13,14,16,17 and four unpublished studies mostly from developing countries. Most participating studies provided detailed information on type and period of prenatal supplementation, alcohol consumption, and disease classification. Data from two studies in the United States, one including 56 children with ALL 12 and the other limited to children with Down's syndrome diagnosed with ALL and AML 11 were not included in our analyses; however, this likely had a no tangible impact on our results. Moreover, consistent with our findings, both studies reported decreased risks of childhood ALL associated with prenatal maternal vitamin intake.11,12 While standardizing data across studies may introduce non-differential misclassification of exposure (and possibly underestimate the risk), pooling data from countries with different socioeconomic backgrounds provides substantial variation in vitamin use, therefore probably increasing the opportunity to detect associations overall.

Previous analyses pooling original data from observational studies or clinical trials have adjusted for study center to account for measured and unmeasured (or unidentifiable) differences in designs and backgrounds,25 or have conducted meta-analyses with published results using fixed or random effect models. 25-27In our pooled analyses, the inclusion of study center as a variable in the logistic regression models had a substantial impact on all risk estimates. This was especially true for studies exhibiting the largest heterogeneity in vitamin/folic acid use; however, other study characteristics could not be identified as possible sources of heterogeneity. Also, adjusting for study center substantially improved the goodness of fit of the models. The sensitivity analyses excluding studies indicated that the results for childhood ALL were robust for supplementation at any time and during pregnancy, and to a lesser extent before conception. Results for AML were less precise overall because of small numbers. Results from meta- analyses were consistent with the study-adjusted pooled analyses for all types and periods of interest, except the preconception period for which we have the least data (data not shown).Therefore, we chose to present only the results of pooled analyses of individual data, as this method allows for a transparent evaluation of the possible impact of study heterogeneity on the risk estimates, and more flexibility to assess subgroup and modifying effects, as well as goodness of fit of the models.

In the 1990s, folic acid supplementation was recommended before conception and during early pregnancy because of its role in preventing neural tube defects.8 Multi-vitamins containing folic acid were later recommended for the additional benefit of preventing a larger spectrum of birth defects and perinatal conditions.8 Folic acid is the synthetic form of folate, which is involved in DNA synthesis, repair, and methylation 3, while vitamins such as C and D are known to prevent oxidative stress, 4,5 thus playing a critical role against carcinogenesis. Low folate levels have been associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer and possibly other solid cancers in adults; however, the association between high-dose folic acid supplementation and increased cancer incidence is still controversial.28-32

The approximate calendar periods during which the use of folic acid was recommended spanned from 1992 to 2002 in the countries that we studied (Table 1). Further, the recommendations varied over time and by country, including dosage (0.36 mg to 0.8 mg per day), time windows (peri-conception/early pregnancy or throughout pregnancy), schedule (daily or weekly), and the composition of multivitamins.8 Similarly, fortification of grain products with folic acid was introduced at different calendar periods across countries.33 Detailed information on dietary and supplementary sources of folate was not available in most participating studies, and therefore could not be directly accounted for in our analyses; however, adjusting for study center likely accounted for some geographical, temporal and social differences.

In our study, supplementation with any vitamins and folic acid any time prenatally was associated with a 15% and 21% reduction in childhood ALL risk, respectively, suggesting that vitamins other than folic acid are unlikely to contribute to additional risk reduction. The interpretation of these findings should take into consideration that folic acid intake is likely to be more specific compared to vitamins, which is a more heterogeneous exposure variable. In contrast for childhood AML, folic acid intake was associated with a 32% reduction in risk, whereas no significant decreased risk was seen with vitamin intake. The observed difference in AML risk by type of supplementation may be due to chance. Information on doses of folic acid and other vitamins was not available for most studies; however, taking vitamins or folic acid throughout the pregnancy seems to be important in preventing childhood ALL, rather than supplementation targeted in early pregnancy, as originally indicated for preventing neural tube defects.

We found that the reduced risk of childhood ALL and AML associated with prenatal supplementation, especially with folic acid, was more pronounced in families with lower education levels. In our study, the lower prevalence of alcohol consumption (a known folate antagonist) observed among mothers with lower education levels may have contributed to these observations. Overall, mothers of children with low education were less likely to use prenatal supplementation, and to have given birth after food fortification with folic acid; and this was true for both cases and controls (data not shown). Also, parental education may have been a surrogate for other unmeasured lifestyles and sociodemographic determinants. Alternatively, differential maternal recall or genetic background among individual study populations may have contributed to differential leukemia risks by education. While the distribution of education levels by case- control status varied among participating studies (i.e., lower education in cases vs. controls in 8 studies, lower education in controls vs. cases in 2 studies, and no difference between cases and controls in 3 studies), it is difficult to anticipate the impact on the overall pooled risk estimates.

The majority of infants with leukemia present rearrangements of the MLL gene located at chromosome 11q23, which may result from targeted insults by specific dietary and environmental agents.34,35 Our stratified analyses by age at diagnosis were inconclusive. Null findings were previously reported between prenatal vitamin and intake and infant leukemia risk, with the possible exception of those with the MLL+ gene fusion.36 Also, a reduced frequency of the low-function variant of the 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene (C677T) was reported in ALL/MLL+ infants compared to cord blood samples.37 CLIC is working toward obtaining and validating data on cytogenetic and molecular characterization of leukemia cases across studies in order to perform these subtype-specific analyses previously.

In conclusion, taking into consideration both strengths (inclusion of published and unpublished data, large sample size for main and subgroup analyses, diversity in exposures, and ability to conduct sensitivity analyses) and limitations (lack of specificity in type and dose of vitamins and other minerals, possible recall and selection biases in individual studies), the results of our pooled analysis indicate that maternal prenatal supplementation with vitamins and/or folic acid reduced the risk of childhood ALL, and that education, as a crude surrogate for lifestyle and socio-demographic characteristics, may modify the magnitude of the associations. Limited data for childhood AML also suggest that maternal supplementation with folic acid, but not vitamins, reduces the risk of this rarer subtype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our dear colleague and friend, Patricia Buffler, who passed away before the submission of this manuscript. She was a founding member and Chair of CLIC. She provided unconditional support to finding the causes of childhood leukemia, and her scientific leadership and guiding forces within CLIC will be remembered. We also would like to thank Somdat Mahabir (NCI, USA), and Denis Henshaw and Katie Martin (CHILDREN with CANCER, UK) for the scientific and administrative support to CLIC. We also would like to thank the families for their participation in each individual CLIC study.

Additional acknowledgements for CLIC studies are provided in Appendix 1.

Funding: The pooled analyses were supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), USA (R03CA132172). CLIC administration is supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), USA (P01 ES018172), the Environmental Protection Agency, USA (USEPA, RD83451101), and the CHILDREN with CANCER, UK. The NCI provided support for teleconferences between CLIC Members. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NCI, NIEHS, or USEPA.

Abbreviations

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- CLIC

Childhood Leukemia International Consortium

- MTHFR

Methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase

Footnotes

Authorship: Authors who were involved in the planning the analyses (CM, EM, CIR, JDD, JC, BA, and RH); conducted the statistical analyses (CM, KM, and SS), participated in the core writing group (CM, EM, JDD, and CIR). All authors ((except KM, SS, AYK and RH) are principal investigators, co-investigators or designates of participating CLIC studies. All authors have reviewed the intellectual content and approve of the final version submitted for publication.

Conflict of interest: None declared

References

- 1.Ries LAG, Smith MA, Gurney JG, et al. Cancer Incidence and Survival Among Children and Adolescents: United States SEER Program 1975–1995. 99-4649. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Stiller CA, Draper GJ, Bieber CA. The international incidence of childhood cancer. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:511–520. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duthie SJ. Folic acid deficiency and cancer: mechanisms of DNA instability. Br Med Bull. 1999;55:578–592. doi: 10.1258/0007142991902646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman M, Bostick RM, Kucuk O, Jones DP. Clinical trials of antioxidants as cancer prevention agents: past, present, and future. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1068–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traber MG, Stevens JF. Vitamins C and E: Beneficial effects from a mechanistic perspective. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1000–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AMigou A, Rudant J, Orsi L, et al. Folic acid supplementation, MTHFR and MTRR polymorphisms, and the risk of childhood leukemia: the ESCALE study (SFCE) Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1265–1277. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dockerty JD, Herbison P, Skegg DC, Elwood M. Vitamin and mineral supplements in pregnancy and the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goh YI, Koren G. Folic acid in pregnancy and fetal outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28:3–13. doi: 10.1080/01443610701814195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen CD, Block G, Buffler P, Ma X, Selvin S, Month S. Maternal dietary risk factors in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:559–570. doi: 10.1023/B:CACO.0000036161.98734.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milne E, Royle JA, Miller M, et al. Maternal folate and other vitamin supplementation during pregnancy and risk of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the offspring. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2690–2699. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross JA, Blair CK, Olshan AF, et al. Periconceptional vitamin use and leukemia risk in children with Down syndrome: a children's Oncology group study. Cancer. 2005;104:405–410. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarasua S, Savitz DA. Cured and broiled meat consumption in relation to childhood cancer: Denver, Colorado (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01830260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schüz J, Weihkopf T, Kaatsch P. Medication use during pregnancy and the risk of childhood cancer in the offspring. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:433–441. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0401-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw AK, Infante-Rivard C, Morrison HI. Use of medication during pregnancy and risk of childhood leukemia (Canada) Cancer Causes Control. 2004;15:931–937. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-2230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson JR, Gerald PF, Willoughby ML, Armstrong BK. Maternal folate supplementation in pregnancy and protection against acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in childhood: a case-control study. Lancet. 2001;358:1935–1940. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06959-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen W, Shu XO, Potter JD, et al. Parental medication use and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2002;95:1786–1794. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kwan ML, Jensen CD, Block G, Hudes ML, Chu LW, Buffler PA. Maternal diet and risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Public Health Rep. 2009;124:503–514. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metayer C, Milne E, Clavel J, et al. The childhood leukemia international consortium. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Kunst A, et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in risk factors for non communicable diseases in low-income and middle-income countries: results from the World Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:912. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James WPT, Nelson M, Ralph A, Leather S. Socioeconomic determinants of health-The contribution of nutrition to in equalities in health. Brit Med J. 1997;314:1545–1549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7093.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prättälä R, Hakala S, Roskam AJ, et al. association between educational level and vegetable use in nine European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:2174–2182. doi: 10.1017/S136898000900559X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roos G, Johansson L, Kasmel A, Klumbiené J, Prättälä R. Disparities in vegetable and fruit consumption: European cases from the north to the south. Public Health Nutr. 2001;4:35–43. doi: 10.1079/phn200048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith GD, Brunner E. Socio-economic differentials in health: the role of nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc. 1997;56(1a):75–90. doi: 10.1079/pns19970011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hillman RS, Steinberg SE. The effects of alcohol on folate metabolism. Annu Rev Med. 1982;33:345–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.33.020182.002021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedenreich CM. Methods for pooled analyses of epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology. 1993;4:295–302. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blettner M, Sauerbrei W, Schlehofer B, Scheuchenpflug T, Friedenreich C. Traditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:1–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ressing M, Blettner M, Klug SJ. Systematic literature reviews and meta- analyses:part 6 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:456–463. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vollset SE, Clarke R, Lewington S, et al. B-Vitamin Treatment Trialists' Collaboration. effects of folic acid supplementation on overall and site-specific cancer incidence during the randomised trials: meta-analyses of data on 50,000 individuals. Lancet. 2013;381:1029–1036. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62001-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai WM, Yang B, Chu XY, et al. Association between between folate intake, serum folate levels and the risk of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:1957–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin HL, An QZ, Wang QZ, Liu CX. Folate intake and pancreatic cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis. Public Health. 2013;127:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SY, Ollberding NJ, Woolcott CG, Wilkens LR, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Fruit and vegetable intakes are associated with lower risk of bladder cancer among women in the Multiethnic Cohort Study. J Nutr. 2013;143:1283–1292. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.174920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson M, Relton C, Ueland PM, et al. Serum B vitamin levels and risk of lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:2377–2385. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamers Y. Folate recommendations for pregnancy, lactation, and infancy. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011;59:32–37. doi: 10.1159/000332073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexander FE, Patheal SL, Biondi A, et al. Transplacental chemical exposure and risk of infant leukemia with Mllgene fusion. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2542–2546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross JA. Environmental and genetic susceptibility to MLL-defined infant leukemia. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2008:83–86. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgn007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linabery AM, Puumala SE, Hilden JM, et al. Children's Oncology Group. Maternal vitamin and iron supplementation and risk of infant leukaemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:1724–1728. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiemels JL, Smith RN, Taylor GM, Eden OB, Alexander FE, Greaves MF United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study investigators. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphisms and risk of molecularly defined subtypes of childhood acute leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:4004–4009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061408298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.