Abstract

Internationally-adopted adolescents who are adopted as young children conditions of poverty and deprivation have poorer physical and mental health outcomes than adolescents conceived, born and raised in the US by families similar to those who adopt internationally. Using a sample of Russian and Eastern European adoptees to control for Caucasian race and US born, non-adopted offspring of well-educated and well-resourced parents to control for post-adoption conditions, we hypothesized that the important differences in environments, conception to adoption, might be reflected in epigenetic patterns between groups, specifically in DNA methylation. Thus, we conducted an epigenome-wide association study (EWAS) to compare DNA methylation profiles at approximately 416,000 individual CpG loci from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of 50 adopted youth and 33 non-adopted youth. Adopted youth averaged 22 months at adoption and both groups averaged 15 years at testing, thus roughly 80% of their lives were lived in similar circumstances. Although concurrent physical health did not differ, cell type composition predicted using the DNA methylation data revealed a striking difference in the white blood cell type composition of the adopted and non-adopted youth. After correcting for cell type and removing invariant probes, 30 CpG sites in 19 genes were more methylated in the adopted group. We also used an exploratory functional analysis that revealed that 223 Gene Ontology (GO) terms, clustered in neural and developmental categories, were significantly enriched between groups.

Keywords: early life stress, early deprivation, institutional care, epigenetics, whole-genome methylation

Studies in a variety of species have shown that adverse experiences early in life can have long-term effects on development (Meaney & Szyf, 2005). These early effects are broad-ranging, including effects on brain structure and function (Nishi, Horii-Hayashi, & Sasagawa, 2014), immune deficiencies and elevated inflammatory factors (Lewis, Gluck, Petitto, Hensley, & Ozer, 2000; Lubach, Coe, & Ershler, 1995), heightened defensive responding (Meaney & Szyf, 2005) and impaired parenting behavior (Fleming et al., 2002). In human development, adverse childhood experiences are associated with a broad range of poor health behaviors and outcomes (Felliti et al., 1998; Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009). These negative outcomes include increased risk of elevated inflammatory factors and inflammation-related disorders (Coelho, Viola, Walss-Bass, Brietzke, & Grassi-Oliveira, 2014), alcohol abuse (Brady & Back, 2012), mental health disorders (Moffitt & Tank, 2013) and poor educational outcomes (Romano, Babchishin, Marquis, & Fréchette, 2014). While some children exhibit resilience (Cicchetti, 2013) and while we are still searching for the pathways between different types of early adversity and specific outcomes (Humphreys & Zeanah, 2014), the ubiquity of the effects and the long developmental reach has led to an interest in understanding how these experiences “get under the skin” to affect behavioral and physiological development (Hertzman & Boyce, 2010).

Children placed in institutional (orphanage) care early in life and then adopted or fostered into families have served as an important group informing our understanding of neural and physiological correlates of early adverse experiences. These children have experienced a variety of adverse early life conditions, often beginning at conception, that may include impoverishment, exposure to pathogens, abuse, and neglect (Gunnar, Bruce & Grotevant, 2000). Their experiences overlap with those of non-institutionalized children reared in poverty. However, unlike many children reared in adverse conditions, the early and later life experiences of these children differs markedly, allowing a greater understanding of what might be instantiated in biology early that is not changed by placement in well-resourced and supportive families (Zeanah, Gunnar, McCall, Kreppner, & Fox, 2011). On average, families of internationally adopted children in this study are in the upper 20% of family income and typically both parents have at least a college education (Hellerstedt et al., 2008). Observations of the parenting in families who adopt internationally have revealed high levels of sensitivity and responsiveness (Garvin, Tarullo, VanRyzin & Gunnar, 2012). However, parents of children with significant developmental delays are more controlling and directive (Garvin et al., 2012), until the children begin to catch up developmentally (Croft, O’Connor, Keavene, Groothues, & Rutter, 2001). In previous work on the formation of attachment among children adopted from orphanages, our group found that within 8 months of adoption nearly all (95%) have formed an attachment to their adoptive parents, 70% of these are secure, although about 23% are disorganized/disordered patterns of attachment behavior (Carlson, Hostinar, Mliner, & Gunnar, 2014). Consistent with a generally supportive and well-resourced environment, after adoption children exhibit remarkable physical and cognitive catchup growth; however, long-term deficits in a variety of domains still remain, including theory of mind, executive functions and attention regulation, and emotion regulation (Kumsta et al., 2010; Loman, Wiik, Frenn, Pollak, & Gunnar, 2009; Zeanah et al., 2003).

Numerous processes may account for the capacity of early exposures to produce long-term effects even when the period of early adversity lasts only a few years and the time spent in low risk environments consumes most of the child’s developing years. These processes may include learned patterns of behavior that influence a child’s perceptions of their experiences and responses they elicit from others (Stovall & Dozier, 2000), effects on brain development that influence learning capacity (Loman et al., 2013), and impacts on the developing defensive system that may limit children’s engagement of their environment (Tottenham et al., 2010). To explain these findings, studies have been directed towards examinations of stress hormones (Koss, Hostinar, Donzella, & Gunnar, 2014), brain function (ERP; Loman et al., 2013; Vanderwert, Marshall, Nelson, Zeanah, & Fox, 2010), brain structure (Chugani et al., 2001; Hodel et al., 2015; M.A. Mehta et al., 2009; Sheridan, Fox, Zeanah, McLaughlin, & Nelson, 2012), and more recently, molecular processes (Drury et al., 2012). Of particular current interest is the possibility that early experiences influence later outcomes by sculpting the epigenome (Boyce & Kobor, 2015; Hertzman, 1999; Meaney & Szyf, 2005).

Epigenetics refers to modifications of the genome that affect DNA accessibility and potentially alter gene expression, but do not alter the base-pair sequence. (Bird, 2007). One specific and wellunderstood epigenetic modification is DNA methylation, which consists of the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine in a C–G dinucleotide (CpG) of DNA. CpGs are non-uniformly distributed in the genome and tend to be clustered in regions referred to as CpG islands (Illingworth & Bird, 2009). Many genes have a promoter-associated CpG island, and DNA methylation of these islands is often correlated with gene expression levels (Jones, 2012; Weber et al., 2007). DNA methylation is also tightly linked to cell differentiation and identity, with cellular heterogeneity within a given tissue being one of the major predictors of epigenetic variability (Jaffe & Irizarry, 2014; Lam et al., 2012;. Liu et al., 2013).

Recent research has suggested that DNA methylation acts as a principal mechanism by which early-life experiences affect neurobehavioral development (Boyce & Kobor, 2015). Indeed, early environments have been consistently associated with changes in DNA methylation across multiple mammalian species (Lutz & Turecki, 2014). In humans, studies of socioeconomic status (SES) suggest that experiencing low SES throughout childhood is associated with altered DNA methylation (Borghol et al., 2012; Lam et al., 2012; McGuinness et al., 2012) and gene expression (Miller et al., 2009) later in life. Prospective, longitudinal research has shown that parental stress in infancy and early childhood associates with differential DNA methylation in adolescents (Essex et al., 2013). Research on the impact of childhood maltreatment on the epigenome has demonstrated changes in DNA methylation in the brain (McGowan et al., 2009) as well as peripheral tissues (see for review, Lutz & Turecki, 2014). Most relevant to the work presented here, in one study with children in a Russian institution, genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in peripheral whole blood were examined (Naumova et al., 2011). Compared to children reared in poverty in their Russian birth families, those living in an institution showed increased DNA methylation across a number of CpG loci, particularly those located among genes related to immune regulation and cellular signaling.

The purpose of the present study was to examine internationally-adopted youth who had been adopted out of conditions of adversity early in life into families in the upper Midwest of the United States. These youth were compared to similarly-aged youth who had been born and raised in Midwest families of comparable wealth and education to those who adopt internationally. To keep ethnicity consistent, we studied only Caucasian youth. From conception until adoption the youth’s lives were markedly different; from adoption on they lived in comparable environments. Consistent with typical ages for international adoption from Russia/Eastern Europe, we anticipated that two years would be the average age at adoption. Thus, because we tested them in mid-adolescence, roughly 80% of their lives would have been spent in comparable circumstances to the non-adopted youth. Our goal was to determine whether exposure to adverse conditions from conception through infancy left behind a signature of DNA methylation that remained up until mid-adolescence.

Method

Participants

Participants included 50 adolescents adopted from institutions for orphaned or abandoned children in Eastern Europe or Russia (M age = 15.68 years, SD = 1.48, age range=12.75–18.67 years; 25 females) and 33 adolescents of European descent who were raised in their biological families in the United States (M age = 15.41, SD = 1.24; age range=13.01–17.25 years; 18 females). There were no significant differences in age, t=1.17, df=82, ns, or gender, χ2(1)=0.80, ns. The differences in sample size were dictated by finances in this study, designed as a preliminary study of methylation patterns in children adopted from conditions of adversity. More adopted than non-adopted children were tested to allow the opportunity to examine early experience correlates within the adopted group.

Exclusion criteria in both groups included a diagnosis of autism, fetal alcohol syndrome, Downs Syndrome or other major congenital disorder. Adolescents in the Adopted group came into their adoptive families on average at 21.8 months (range: 6–78 mos; SD = 17.16), and had spent 91.6% (range: 56–100%; SD = 12.79) of their pre-adoption lives in institutional care. Reasons for placement in institutional care were not always known to the adoptive families; however, 71% of the adopted youth had never lived anywhere else, another 20% were abandoned by or removed from their families by 6 months of age, while 10% had spent more than 6 months in some kind of non-institutional setting prior entering these institutions. Countries of origin included Russia (34), Romania (6), Ukraine (4), Bulgaria (1), and other Eastern European countries (5).

Adoptedyouth were recruited from a registry of families of internationally-adopted children who were interested in research. The registry reflects approximately 60% of all internationally-adopted children in our catchment area. Youth in this study had previously been in an imaging study when they were 12 and 13 years of age (Hodel et al., 2015). In addition to the exclusion criteria noted above, the adopted youth had also met inclusion and exclusion criteria for magnetic resonance imaging research. The non-adopted, comparison youth were recruited by phone from a registry of families interested in participating in research that was initiated through letters mailed to parents of all live births in our catchment area. Written consent and assent were obtained from the adolescents and their families received monetary compensation. All procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board.

The comparison group was selected to roughly match the adopted group on family income and parent education. At the time of testing, adolescents from both groups lived in families of similar socioeconomic levels with both groups averaging pretax incomes between $85,001 and $100,000 per year and parental educational levels of a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Six participants were not able to provide samples or their samples were excluded because of problems with collection. No youth who had a fever on the day of sampling were included. Sample size and demographics above were reported with these individuals excluded.

Procedure

Adolescents and their primary caregiving parent attended a 2-hour laboratory testing session that included the completion of questionnaires and a blood draw between 0900h and 1100h. Following arrival at the testing site, consent and assent were obtained in a private room, and participants received monetary compensation. Parents and adolescents completed questionnaires in individual rooms and a single vial of blood (7mL) was obtained from the adolescent by antecubital venipuncture. Within one hour of blood draw, samples were transported to the laboratory and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated as previously described (Miller et al., 2009). PBMC pellets were frozen and stored at −80°C until DNA extraction.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Parents completed questions about demographic information (e.g., income, education), lifetime history of the adolescents’ medical and psychiatric diagnoses, current treatments and services, and pre-adoption history (where applicable).

McArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire

(HBQ; Essex et al., 2002) was completed by both parents and youth. The parent version consists of 124 items and the child version consists of 164 items that probe physical and mental health, as well as functioning in academic and social domains. Parent reports of psychiatric diagnoses and current psychotropic medications and parent and youth reports on health problems on the day of testing and in the last month from this measure were used in analyses.

The Life Events Checklist-Child/Adolescent Version

(J. H. Johnson & Cutcheon, 1980) was administered to parents and youth to assess stress during the past year. Adolescents reported whether any of 46 events happened to them, whether the event was bad or good, and what level of impact the event had on them. Negative events with no impact were coded as 0, some = 1, moderate = 2, great = 3, and the total of these events were summed for a total number of negative life events in the past year. Parent and youth reports were correlated (r=0.42, p<.001) and were averaged to stabilize the measure.

DNA Methylation

DNA was extracted from PBMC pellets using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Bisulfite conversion of DNA was performed with the EZ-DNA methylation kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). Bisulfite converted DNA was interrogated with the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Background subtraction and color correction of data was performed using Illumina GenomeStudio software, at which point data were imported into R for further pre-processing (R Team, 2008).

Data pre-processing

Technical replicates and expected sex of each participant were checked to ensure consistency. Next, the 65 SNP probes, 11,648 X/Y chromosome probes, 2,751 probes not detected above background in at least one sample, 15,747 probes with less than 3 beads contributing to the signal in at least one sample, and 39,440 probes we have previously shown to exhibit poor design features were filtered out, leaving a final total of 415,926 probes (Price et al., 2013). DNA methylation data was quantile normalized using the lumi package, and SWAN normalization was performed to correct for probe type (Du, Kibbe, & Lin, 2008; Maksimovic, Gordon, & Oshlack, 2012). Finally, ComBat was performed on the data to remove chip and row effects sequentially (Chen et al., 2011). Both iterations of ComBat included adoption status and sex as additive effects in the model, identifying them as important variables for which variance should be protected.

Cell type composition of samples was determined using published methods (Houseman et al., 2012 ; Koestler et al., 2013). Data was adjusted for cell composition by fitting probewise linear models using predicted cell composition as variables and scaling the DNA methylation data using the resulting residuals (Jones, Islam, Edgar & Kobor, 2015). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on a matrix of normalized M values using the prcomp function with centering in R. Resulting loadings were correlated with sample variables using a Spearman’s correlation.

Data Analysis

We first examined the data for potential covariates by determining which variables might be significantly different by group. Those differing by group were then subjected to further analyses to determine whether they also were associated with DNA methylation. These latter analyses were performed using the limma package (Smyth, 2005). After determining the covariates needed in the analyses a differential DNA methylation analysis was performed on all probes on the array, again using the limma package (Smyth, 2005). This was first done on the non-cell-type-adjusted data to determine the effect of not correcting for these important differences (Smyth, 2005). Permutations were performed in exactly the same way, except that group assignments were randomized 100 times, and resulting p-value distributions plotted.

To conserve power, since it has been shown that most sites of DNA methylation are invariable across individuals (e.g., Smith et al., 2015), we performed a filtration step to remove any invariable sites, defined as having a SD less than 0.05, or 5% methylation. This step removed 407,156 sites, resulting in a final list of 8,770 variable sites. These invariable sites have been repeatedly identified in the literature as making up the majority of total CpGs, and generally represent constitutively methylated or unmethylated sites that are less likely to be associated with gene expression, and this filtration has been used in a number of studies (Bourgon et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2015; Teh et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2014). Thus, this step ensures that that multiple test correction will not be unduly penalized for measurements with no underlying variability. Analysis on this filtered data set was performed using the lm function from the stats package with age, sex, and negative life events as covariates.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

First, we matched each probe to a single gene name in the following manner: i) sites with no Illumina-annotated UCSC_refgene name were annotated as NA; ii) sites with one or more gene name entries in the Illumina-annotated UCSC_refgene_name and where all gene names were identical were annotated to the given gene; iii) sites with multiple gene name entries in the Illumina-annotated UCSC_refgene_name and where gene names differed, were annotated to the closest transcription start site (TSS) based on the annotation in the Closest_TSS_gene_name column from a published re-annotation (Price et al., 2013). A Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed on uncorrected p-values using ErmineJ, and gene names were ranked by lowest p-value for any associated CpG (Gillis, Mistry, & Pavlidis, 2010 ). ErmineJ parameters were as follows: Gene Score Resampling method, 5–100 cluster size, best scoring replicates, negative log of p-values and mean for clusters. For functional clustering, ErmineJ output was separated into a gmt file containing GO terms and associated genes, and a text file containing ranked GO terms, FDR adjusted p values, and multifunctionality values, which were added to the normal FDR p-value column for graphical purposes. These files were input into cytoscape for clustering analysis using EnrichmentMap with the following parameters : p-value 0.05, fdr p-value 0.99 (here representing multifunctionality), Jaccard and Overlap combined coefficient 0.5. Only clusters with five or more members were visualized. Each resulting cluster was named using WordCloud, where the top ranking word was used, unless a second word was required to make an understandable term in which case both were used.

Results

Determining Covariates

In order to create an appropriate model by which to test DNA methylation differences associated with adoption status, we first examined potential covariates. Numerous variables were examined for group differences. Those exhibiting differences were parent (but not youth) report of internalizing, externalizing and ADHD symptoms, Hotelling’s F(3,78)=5.18, p<.01. Groups differed in psychiatric diagnoses with 41% of the Adopted and only 13% of the Non-adopted group carried any psychiatric diagnosis, χ2(1, N=83)=7.44, p<.01. Most often for the Adopted youth the diagnosis was ADHD with 31% of the Adopted and 3% of the Non-adopted carrying that diagnosis, χ2(1, N=83)=9.29, p < 0.01. There were no group differences in diagnoses of depression or anxiety (p’s > 0.10). Consistent with differences in diagnoses, Adopted adolescents (31%) were more likely to be taking psychotropic medication than were Non-adopted youth (13%), χ2(1, N = 83) = 3.77, p =.05. We averaged parent and youth report for negative life events with the impact scores for the time period the children were in their current families. There were no significant group differences, F(1,81)=0.28, ns. This was also true for negative events in the past 12 months as an average of parent and child report, t(81)=−0.19, p=0.85. Finally, health problems reported in the last month yielded a non-significant trend towards significance with 11% of Non-Adopted and 25% of Adopted youth experiencing one or more health problems in the month prior to testing, χ2(1, N=83)=3.2, p=0.07.

We then examined these variables to determine their association with DNA methylation. We found no evidence that any of the parent reported scores for internalizing, externalizing or ADHD or whether the child was diagnosed or being medicated for a psychiatric disorder was associated with DNA methylation. Only negative life experiences was shown to have a signature independent of other covariates, so it, along with age and sex, was included as a covariate in all subsequent analyses. Negative life experiences showed two CpGs associated at an FDR of 0.05 but neither showed a mean difference between groups of greater than 2%.

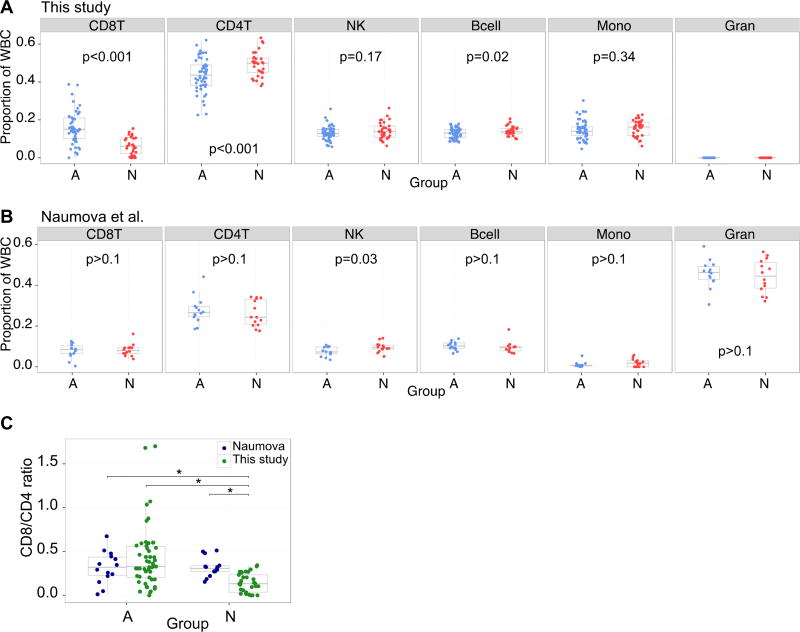

Cell-Type Analysis

Since DNA methylation is highly influenced by cell type, it is essential to account for inter-individual differences in white blood cell distributions between groups. Thus, we next examined whether adoption status was associated with cell type distribution. At the time of blood draw, no complete blood count (CBC) data were collected, so we used a published algorithm to back-predict the underlying cell types from the DNA methylation data (Houseman et al., 2012). Because recent illness can affect the immune cells in circulation, we first tested whether the 17% of participants who had experienced health problems in the last month differed in cell type composition from those who had not. None of the t-tests were significantly different (p’s > .20). We next tested whether cell type composition differed between Adopted and Non-adopted participants, and found a marked difference between the groups (Figure 1A). We compared each cell type across the two groups using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. As shown, there were significantly fewer CD4+ T cells and more CD8+ T cells in the adopted compared to the non-adopted youth. In addition, B cells were lower in frequency in the adopted than non-adopted youth. These analyses indicate how essential it is to correct for inter-individual differences in blood cell-type composition in order to avoid spurious DNA methylation findings; hence in subsequent analyses cell type was controlled.

Figure 1.

White blood cell type proportions differed between Adopted and Non-Adopted youth in this study but not in a previously published data set. A and B) Proportion of white blood cell types as predicted using a published algorithm are shown separated by Adopted (blue) and Non-Adopted (red) in our study (A), and a previously published study (B). Boxes are box and whisker plots of the 25th, 50th and 75th percentile. Indicated p values are the result of unpaired t tests comparing the distribution of the two groups. [(CD8T=CD8+ T cells, CD4T=CD4+ T cells, NK=natural killer cells, MONO=monocytes, GRAN=granulocytes. Note that no granulocytes were estimated because these are mononuclear cells]. C) Ratios of CD8/CD4 T cells differed between the non-adopted participants in this study and the other groups.

To further explore factors that might be driving this cell type difference, we focused on the CD4/CD8 ratio, which may reflect immune competence. We examined it in relation to each of the potential covariates that differed by group. No significant correlations were obtained for use of psychiatric medication, average negative life events, and negative life events in the last 12 months, df’s=79, r’s< .15, p’s > .20. Youth with more externalizing symptoms, r(79)=−.26, p<.05 and ADHD symptoms, r(79)=−.35, p< .01 did exhibit a lower CD4/CD8 ratio. However, when we entered these factors as covariates, the group difference between Adopted and Non-Adopted youth was still highly significant, F(1,76)=11.33, p<.001. It should be noted that while none of the youth had a fever on the day of testing, some reported mild cold or allergy symptoms. These did not differ by group, but were correlated with CD4/CD8 ratios, r(79)=.35, p<.001.

The finding of cell-type differences was remarkable in itself. Thus, before attributing these differences to institutional care, we took advantage of a previously published study that also examined effects on DNA methylation of institutionalization in Eastern European children that used the older 27k array (Naumova et al., 2011). That study compared children in institutions to similarly impoverished children living in their families in Russia. The researchers supplied us with their data and we applied the same back-prediction algorithm (Houseman et al., 2012). We did not observe the same CD4/CD8 T cell ratio between groups, and noted that both groups of impoverished Russian children had lower CD4/CD8 ratios than the Non-Adopted US born group and comparable to the Adopted Russian/Eastern European group (Figures 1B, 1C).

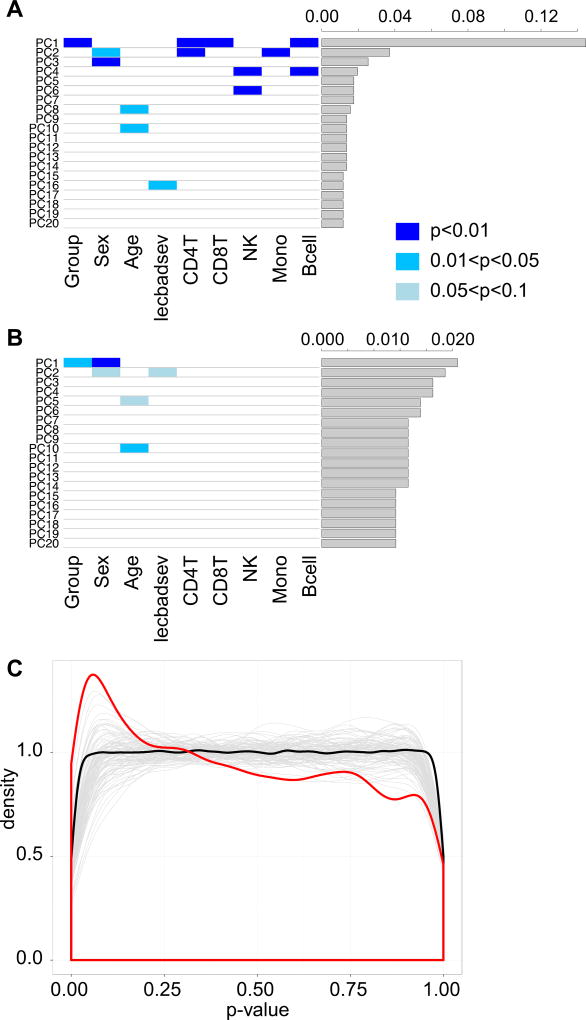

DNA Methylation Analysis Without Cell-Type Correction

Given that we knew that differences in cell type composition existed between our groups, we sought to compare DNA methylation differences between the groups with and without cell type correction, to emphasize the importance of this step. This analysis is timely considering that correcting for cell type has only recently emerged as an important aspect of epigenetic population studies. We first used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the non-cell type corrected data. This PCA (Figure 2A) revealed large DNA methylation signals associated with adoption group, sex, age, and negative life experiences, but also with cell types. We then proceeded to determine specific DNA methylation changes associated with adoption status, controlling for age, sex, and negative life events. Without correcting for cell type, using a Storey’s (2003) qvalue of 0.1 and minimum group mean beta value difference of 0.02, 136,339 sites were differentially methylated between the two groups (data not shown). We tested these sites to compare overlap with sites that were previously observed to be differentially methylated by cell type, and of the 136,339 sites, 109,961 were found in a previous paper to be associated with one or more cell type at a false discovery rate of 0.05 (Jaffee & Irizarry, 2014). This implies that, for studies where cell type proportions are correlated with the variable of interest, the majority of hits are in fact sites that differ directly due to cell type composition and not the variable if cell composition is not taken into account.

Figure 2.

Blood cell type is an important and confounding factor in the analysis of DNA methylation and adoption status. On the left, heatmaps of significance between top 20 principal component scores and variables of interest. On the right, histograms of the proportion of variance accounted for in the data by the indicated principal component. A) Prior to correction for cell type, principal components were significantly associated with adoption status (Group), the covariates of interest, and all cell types. B) After correction for cell type, association with cell types is no longer present, and both significance level and proportion of variance for the Group-associated principal component has decreased. C) Density plot of uncorrected p-value distribution for linear model on 415,926 probes (red line). Left skewing indicates enrichment for very small but non-significant p values. Grey lines represent similar distributions for 100 permutations of group assignment, summarized by a mean line in black.

DNA Methylation Analysis With Cell Type Correction

We then repeated these analyses on data that had been corrected for cell type composition. In the PCA, after regressing out differences due to cell type composition, the signal associated with adoption status was greatly reduced in both significance and magnitude of variance (Figure 2B). DNA methylation signals associated with age, sex, and negative life events remained, but also at a much lower proportion, as would be expected given age, sex and stress associations with T cell composition (Pérez-de-Heredia et al., 2015; Stefanski & Engler, 1998) (Figure 2B). We next performed our linear modeling on this cell type corrected data, using the same covariates, age, sex, and negative life experiences. With the same significance criteria (i.e., a qvalue of 0.1 and minimum group mean beta value difference of 0.02), no sites were significantly different between adoption groups. However, the unadjusted p-values showed a pronounced leftward skew (Figure 2C, red line). We permuted the group assignments 100 times and repeated the linear modeling, which resulted in a predominantly flat background distribution of p values, indicating that our left skewed distribution did indeed show enrichment for low p values beyond the expectation by chance (Figure 2C, black line).

Since it has been shown that most sites of DNA methylation are invariable across individuals (e.g., Smith et al., 2015), we next performed a filtration step to remove any invariable sites. This filtration step removed any site with a standard deviation of less than 0.05, and resulted in a final list of 8,770 variable probes. This filtering removed sites with no underlying variability, thus reducing the burden of multiple test correction and increasing the power to identify the sites responsible for the leftward skew in Figure 2C. Using qvalue of 0.1 and minimum mean difference of 2% methylation between groups, there were 30 differentially methylated sites in 19 different genes. Genes with more than one CpG found to be differentially methylated included TMEM200C (4), PPP1R3G (3), GLYATL2 (2), CYP1A1 (2), and miR-324 (2). A full list, including specific gene functions and mean difference between groups, is found in Table 1. None of these 30 CpGs showed correlation between DNA methylation beta value and percent composition of any cell type in our samples (maximum absolute Spearman ρ=0.17).

Table 1.

Thirty Differentially Methylated Genes between Adopted and Non-Adopted Youth Ordered by Number of Sites and Chromosome

| Gene Symbol | # of CpGs |

delta beta | Chr | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMEM200C | 4 | −0.046* | 18 | Transmembrane protein 200C | Transmembrane protein with no specifically identified function. |

| PPP1R3G | 3 | −0.042* | 6 | Protein Phosphatase 1, Regulatory Subunit 3G | Involved in glucose homeostasis and glycogenesis in the liver (Luo et al., 2011; Y. Zhang et al., 2014) |

| GLYATL2 | 2 | −0.044* | 11 | Glycine-N-Acyltransferase-like 2 | Acetylation-regulated glycine acyltransferace expressed in salivary gland, trachea, spinal cord, and skin (D.P. Waluk et al., 2010; D.P. Waluk, Sucharski, Sipos, Silberring, & Hunt, 2012) |

| CYP1A1 | 2 | −0.042* | 15 | Cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily 1, polypeptide 1 | Cytochrome linked to drug metabolism, genetic variants associated with lung cancer risk, and methylation associated with exposure to cigarette smoke(Joubert et al., 2012; Shenker et al., 2013) |

| miR-324 | 2 | −0.048* | 17 | Micro RNA 324 | miRNA with two validated targets, GLI1 and SMO, both involved in neuron differentiation.(Ferretti et al., 2008) |

| SFRP2 | 1 | −0.037 | 4 | Secreted frizzled-related protein 2 | Wnt family receptor regulating apoptosis response to Tumour Necrosis Factor. Evidence of epigenetic silencing in cancer. (Melkonyan et al., 1997; Perry et al., 2013; Saito et al., 2014) |

| ADAMTS2 | 1 | −0.056 | 5 | ADAM metallopeptidase with thromobospondin type 1 motif, 2 | Highly processed enzyme with multiple isoforms and different functions in collagen metabolism. Mutations in this gene have been associated with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VIIC, a connective tissue disorder. (Colige et al., 2004; Colige et al., 2005) |

| ESM1 | 1 | −0.047 | 5 | Human endothelial-cell specific molecule-1 | Endothelial cell-specific and cytokine-regulated secreted protein involved in immunity and inflammation. (Lassalle et al., 1996; W. Lee, Ku, Kim, & Bae, 2014) |

| Mir-873 | 1 | −0.048 | 5 | Micro RNA-873 | Regulator of inflammatory cytokines in white blood cells and brain |

| CFTR | 1 | −0.057 | 7 | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator | Ion channel expressed in multiple tissues , responsible for Cystic Fibrosis (Riordan et al., 1989) |

| CALCB | 1 | −0.032 | 11 | Calcitonin-related polypeptide beta | Putative secondary peptide expressed from the CALC locus, which produces both calcitonin and a calcitonin gene-related neuropeptide, both expressed in brain and involved in inflammation (Hou et al., 2011) |

| OR4C13 | 1 | −0.052 | 11 | Olfactory Receptor, 4 C 13 | Olfactory receptor (Malnic, Godfrey, & Buck, 2004) |

| ATP8A2 | 1 | −0.045 | 13 | Aminophospholipid transporter, class I, type 8A, member 2 | A protein-coding gene involved in phospholipid-translocating ATPase activity expressed in the brain and retina (Coleman et al., 2014) |

| AJ278121 | 1 | −0.039 | N/A | Unannotated ORF | |

| TPM1 | 1 | −0.049 | 15 | Tropomyosin alpha chain 1 | An actin-binding protein involved in the contractile system of striated and smooth muscles an drequired for proper cardiac development. (McKeown, Nowak, Gokhin, & Fowler, 2014) |

| FAM215A | 1 | −0.043 | 17 | Family with sequence similarity 215 member A | Unannotated possible ncRNA |

| LOC730755 | 1 | −0.042 | 17 | Unnamed locus | Uannotated locus with sequence similarity to keratin associated protein |

| ALKBH7 | 1 | −0.035 | 19 | AlkB, E. Coli, Homolog of, 7 | Involved in alkylation and oxidation induced necrosis and obesity (Wang et al., 2014) |

| CERK | 1 | −0.091 | 23 | Ceramide Kinase | Kinase involved in the metabolism of sphingolipids, shown to be involved in immunity and inflammation (Bornancin, 2011) |

indicates average delta beta of all underlying CpGs

We next set out to compare our results to the previously published data set used for cell type analysis above (Naumova et al., 2011), First, we identified an overlap of four CpGs (cg00520135/TPM1, cg05968233/ALKBH7, cg06938878/CALCB and cg20359349/FAM215A) between our 30 hits and the CpGs present on the 27k array used in the previous study. None of these four showed differential DNA methylation between adopted and non-adopted participants in that data set. We also examined the 914 sites the previous study identified as significantly differentially methylated between groups (Naumova et al., 2011). Of these, 213 were in our list of 136,339 significantly different sites before the cell type correction. Only 64 of the remaining showed variability in our sample, and none were differentially methylated between groups in our data set. There are many possible reasons for this lack of replication, including differences type or severity of early life experiences and the fact that the Naumova participants were still living under conditions of adversity and our participants had not been living under those conditions for many years.

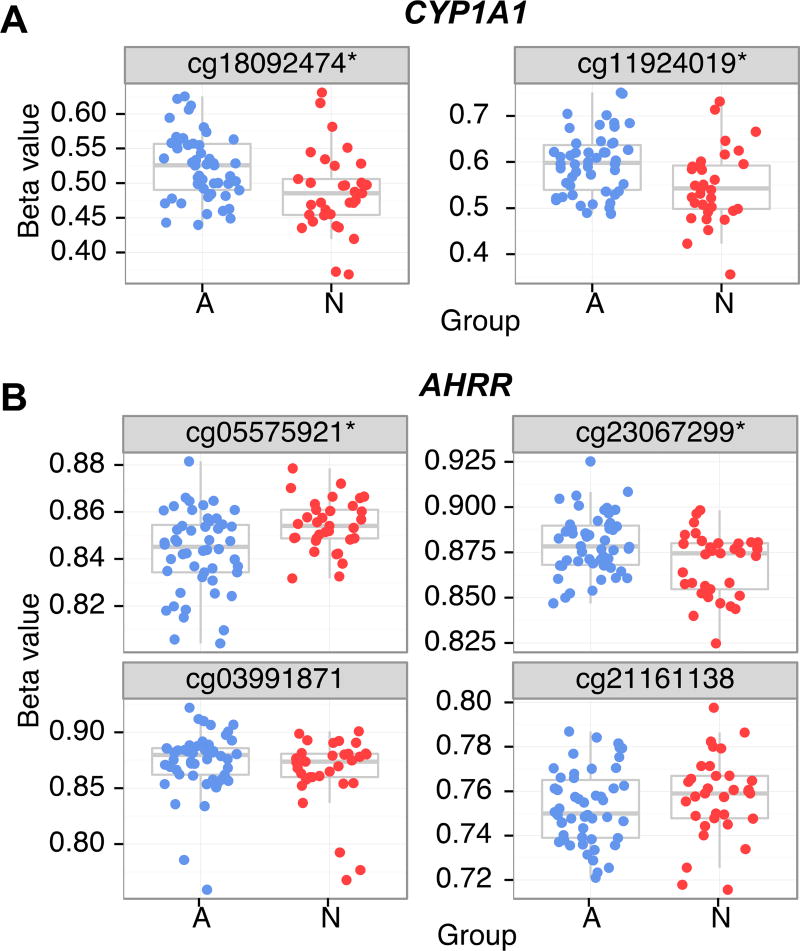

DNA methylation at one of the genes in our hit list, CYP1A1, has previously been associated with exposure to cigarette smoke. Children in orphanages in Russia and Eastern Europe are frequently exposed to cigarette smoke in the institutions (Gunnar, Bruce and Grotevant, 2000). To determine whether this would be a reasonable interpretation of this finding, we further examined the AHRR gene, which is the gene with the best replicated finding of DNA methylation due to smoke exposure. We examined 11 papers that had published associations between methylation and AHRR and cigarette smoke, and determined that five CpGs were found in more than three of these studies (Dogan et al., 2014; Elliott et al., 2014; Joubert et al., 2012; K. W. K. Lee et al., 2015; Markunas et al., 2014; Monick et al., 2012; Novakovic et al., 2014; Richmond et al., 2015; Shenker et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2013; Tsaprouni et al., 2014). Four of these five CpGs were present in this data set, so we tested their DNA methylation using the same linear model as the whole genome analysis. Two of these four sites in AHRR (cg05575921 and cg23067299, p’s <.01) showed differential DNA methylation based on adoption status, in the expected direction of change based on higher cigarette smoke exposure in adopted than non-adopted children (see Figure 3). This implies that the observed differential methylation in CYP1A1 may be due to our Adopted participants having had higher early life exposures to cigarette smoke. Of course, it could also be that the Adopted youth were more likely to be smoking currently than were the Non-Adopted Youth. Although we did not have a measure of youth smoking, we did have the parent report of externalizing problems which did differ by group and is, by definition, associated with conduct problems in adolescence such as illegally smoking. When we added externalizing symptoms as a covariate in the analysis of CYP1A1, it did not reduce the association with group.

Figure 3.

DNA methylation findings were supportive of higher cigarette smoke exposure in adopted participants. A) CYP1A1 was more methylated in adopted (A, blue) than non-adopted (N, red) participants at two sites as found in the EWAS analysis. B) to validate this, four CpGs in the AHRR gene were examined for differential DNA methylation between adopted and non-adopted participants. Two, cg05575912 and cg23067299 (indicated with an asterisk), were significantly differentially methylated at an FDR of 0.05.

Functional Analysis

As a final exploratory analysis, we performed a functional analysis as described in the methods. The specific method used, ErmineJ, requires the full, unfiltered dataset to uncover broader epigenetic signatures related to these groups. We first mapped each probe on the 450K array to a unique gene name and created a background list of all genes present in the 415,926 remaining probes and their associated GO terms. We then tested for significant enrichment of particular Gene Ontology (GO) terms at the top of a list of genes ranked by their uncorrected p value for differences between groups. Two hundred and twenty three GO terms were significantly enriched at the stringent program-selected false discovery rate of 0.05. Important to note in this analysis is the phenomenon of multifunctionality. Multifunctional genes tend to be highly studied and thus associated with many GO terms, so the presence of multifunctional genes at the top of a list would tend to lead to a large number of GO terms showing significance.

To further refine this functional analysis and group these GO terms in larger functional units, we clustered the GO terms according to shared genes (Merico, Isserlin, Stueker, Emili, & Bader, 2010; Shannon et al., 2003). The resulting functions can generally be clustered into two categories, neural (Neuron, Behavioral Response, Action Potential, and the large Regulation cluster) and developmental (Organ Induction, Nephron Tubule Development, Pattern Specification, BMP Signaling, and the large Morphogenesis cluster) (Figure 4). Given the large number of multifunctional genes in this list, it was not surprising that many of the GO terms were also highly multifunctional.

Figure 4.

Whole-genome EWAS found a signature of association between adoption status and DNA methylation, and functional analysis revealed many neurological and developmental processes. B) Enrichment map for GO terms significantly enriched in EWAS with an FDR<0.05 assessed by ErmineJ. Only clusters with four or more GO terms were included in this figure, and cluster names were assigned by WordCloud. GO terms are represented by nodes, node size indicates number of genes in each term and node color indicates multifunctionality score for each term. Edge width indicates number of shared genes between terms.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine differences in the epigenomes of immune cells in peripheral blood in adolescents adopted as young children from conditions of significant adversity. This adversity took the form of early adversity these youth had experienced was birth to women in Russia/Eastern Europe who gave up their parental rights and placed their infants in institutions/orphanage where they were reared for the first few years of life. Following this, the children were adopted into well-resourced families in the United States. Initially, we estimated the underlying white blood cell composition in these participants with the goal of controlling for it, and noted drastic differences in CD4T/CD8T cell ratios. After correcting for these cell type differences and restricting the analysis to variable CpG loci, 30 sites on 19 genes met criteria for differential DNA methylation by adoption group. We also conducted a functional analysis of GO terms and found that group differences clustered in two areas: neuronal and developmental. These results are consistent with behavioral and health differences frequently noted for children adopted from this region of the world following orphanage rearing (Kumsta et al., 2010; Loman,et al., 2009; Zeanah et al., 2003). However, there are a number of reasons to view these data as only suggestive of early adversity effects as the many differences between the adopted and non-adopted youth leave open other explanations that will be discussed below.

Before discussing the DNA methylation findings, it is important to note both the cell-type differences and the effects of correcting versus not correcting for those differences. The adopted and non-adopted youth differed strikingly in the type of immune cells in circulation. Specifically, the adopted youth exhibited fewer CD4+ and more CD8+ cells than the non-adopted youth and fewer B cells. This pattern suggests a reduced immune competence which may have some adaptive significance in the environment in which these children were conceived and reared prior to adoption. The difference was not explained by significant health differences in the month prior to blood sampling, nor was it explained by externalizing and ADHD symptoms, even though these variables differed between groups and correlated with the CD4/CD8 ratio. In the field of psychoimmunology, many animal studies have documented that a variety of early adversity affects the differentiation of T cells within the thymus and their circulating numbers (Eriksen et al., 2014). Reduced CD4+ and increased CD8+ T cells in circulation also has been noted recently in adolescent Rhesus monkeys who were maltreated as infants (Kohn et al., 2014). As in the present study, living conditions were comparable for the maltreated and comparison monkeys after weaning. The present finding is also consistent with evidence that post-institutionalized youth are impaired in containing the Herpes simplex virus with titers that are even higher than those of youth in child protection for physical abuse (Shirtcliff, Coe, & Pollak, 2009).

However, as noted earlier, in the present study many factors from conception until adoption differed between the adopted and non-adopted children. Only once the children were adopted were the two groups comparable in their physical and social care. To be sure that we did not misattribute the cell type differences, or other methylation differences, to institutional care versus the general context of being born into poverty in Russia/Eastern Europe, we obtained the DNA methylation information from a study of impoverished Russian children, some raised by their families and some living in Russian orphanages (Naumova et al., 2011). Using the same techniques to back-predict cell type that we used on our data (Houseman et al., 2012), we estimated the CD4+ to CD8+ ratio in the Naumova data set. The results showed that the adopted children in this study looked very similar in CD4/CD8 ratios to both family and orphanage-reared poor children in Russia and all three groups appeared somewhat immunosuppressed compared to non-adopted children conceived, born and reared in well-resourced families in the United States. Thus, the differences between the adopted and non-adopted children in cell types in our sample was not due to institutional care, per se, but would also be observed in other poor children from Russia/Eastern Europe. We should also note, of course, that these differences could also be due to allelic differences between Russian/Eastern European populations and the Americans of European descent (Chami & Lettre, 2014). Follow up studies are needed to replicate these findings through immune-phenotyping and functional analyses of how well the immune systems of children adopted from early adverse conditions combat and contain infections.

Regardless of the explanation for the cell-type difference, the presence of such striking differences would have produced highly spurious epigenetic results had we not controlled for them. The need to control for cell type has been noted by others, but is still not routinely done (Houseman et al., 2012; Lam et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2013). Similarly, a previous study showed that since cellular composition changes with age, accounting for cellular heterogeneity is also critical in any study of DNA methylation and age (Jaffe & Irizarry, 2014). As a demonstration of the importance of cell-type correction, we reported 136,339 methylation differences between groups when we did not correct for cell type, and significantly fewer after correcting for cell type. Because type of tissue/cell type is the primary determinant of DNA methylation patterns, the marked differences in immune cell types in the present study would have yielded a vast over-estimation of methylation differences between groups. Examining cell type and then correcting for it in the present study was clearly vital to determining the true signals of DNA methylation associated with the early life differences between the adopted and non-adopted groups.

After correcting for cell type, none of the specific sites survived correction for multiple testing when we used all of the probes on the array. The p-values, however, were clearly skewed, indicating that there was a signal present that did not reach statistical significance. We addressed this problem in two ways. First, we adjusted the correction factor by removing all the methylation sites that did not show any variation. This data reduction approach is modeled after published studies aimed at reconciling the large number of data points obtaining in genomic DNA methylation or gene expression studies with generally small cohort sizes (Bourgon et al., 2010; Teh et al., 2014). After taking the invariant probes out, we noted 19 genes mapping to the 30 sites that survived correction. These were a varied assortment (Table 1). Transmembrane protein 200C, which had the greatest number of sites that were differentially methylated between groups, is a gene with relatively little known functional information. It was identified as a candidate for genes related to psychiatric illness associated with a pericentric inversion of Chromosome 18 (Pickard et al., 2005), but its function has not been elucidated. PPP1R3G, which had three differentially methylated CpGs, is involved in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in the fasting-feeding cycles and the rise in glucose following a meal (Luo et al., 2011; Y. Zhang et al., 2014). Given that growth delay is associated with early life adversity in impoverished children (Fernald & Grantham-McGregor, 2002) and children in institutional care (D. E. Johnson & Gunnar, 2011), perhaps alterations in a gene involved in regulating energy metabolism in relation to food intake could be expected. GLYATL2 with two differentially methylated sites is a glycine acetyltransferase that is also relatively uncharacterized. It is part of the family of glycine-N-acyltransferase whose biological activities include antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative effects (Waluk, Schultz, & Hunt, 2010). miR-324 has been implicated in both immune function upon infection as well as an animal model of post-traumatic stress disorder (Balakathiresan et al., 2014; Chang et al., 2014). This might reflect the observed differences in immune status of the adopted children and bears further scrutiny. Finally, CYP1A1, also with two differentially methylated CpGs, is a highly multifunctional metabolic enzyme and its differential methylation related to early life adversity may be one of the reasons for the high number of terms in the GO analysis. Interestingly, an increase in DNA methylation of CYP1A1 has been reported in response to exposure to cigarette smoke in early life (K. W. K. Lee et al., 2014). We found higher DNA methylation in the adopted children, which could indicate that they experienced higher exposure to cigarette smoke both before and after birth, consistent with the high rate of smoking in these children’s countries of origin. We supported this finding by examining a subset of CpGs in the AHRR gene that has been associated with cigarette smoke, and although AHRR was not differentially methylated in our full or filtered data set, the pattern observed when we examined it specifically was consistent with increased exposure in the adopted children. This hypothesis was further supported using a subset of CpGs in the AHRR gene that has been associated with cigarette smoke. Notably, exposure to cigarette smoke would not be specific to being institutionally vs family reared. Of course, this difference could be due to the youth taking up smoking themselves. We did not ask about whether the participants were smoking. We did ask the parents to report on externalizing problems, which is associated with teen smoking and which did differ by group. However, when we included externalizing as a covariate in the AHRR gene analysis, the methylation difference was still noted.

Second, we performed a functional enrichment analysis using ErmineJ’s Gene Score Resampling method. We chose this method because it reduces bias by using a rank ordered list of genes and p-values to identify GO terms, and thus is ideal for examining patterns in the larger dataset encompassing all CpG sites (Gillis et al., 2010). Since it does not use a p-value significance threshold, it was appropriate for this analysis and served as its own background. Many of the high-ranked genes in the resulting list of differentially methylated sites had many GO terms associated with them due to multifunctionality. After reducing this effect by performing clustering analysis, the results pointed to two types of genes differentially methylated between groups. Specifically, neuronal and developmental gene clusters resulted, suggesting wide-ranging effects of early life histories.

Many of the functions associated with highly ranked genes in the genome-wide analysis reflected known effects of early life adversity. For example, alteration in renal development is one of the mechanisms linking maternal stress and nutrition to offspring late-life metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease (Barker, 1997). Thus it was noteworthy that one of the clusters from the functional analysis was nephron tubule development. Similarly, BMP (bone morphogenic proteins) signaling may be of particular relevance because of the marked bone growth delay observed among infants and toddlers growing up in institutions (D. E. Johnson & Gunnar, 2011). Certainly, given the numerous differences in cognition and brain structure (Sheridan et al., 2012; Tottenham et al., 2010), it is no surprise that two of the clusters related to the nervous system and its regulation, though it is unclear how our observations in blood reflect changes in brain. It has been shown that concordance between blood and brain is variable between CpGs sites, with some showing greater similarity than others (Davies et al., 2012; Farre et al., 2015). In addition, the many genes with multiple functions related to morphogenesis of the eye and heart may be consistent with vision problems frequently noted among children reared in institutions (Eckerle et al., 2014) and may suggest the potential for cardiovascular disease as these children age.

There were a number of limitations to the current study. First, with a goal of examining the long term impacts of early adversity when it is followed by rearing under low risk conditions, to rule out ethnicity as the key factor, the ideal comparison group would have been non-adopted Russian/Eastern European children reared in families of comparable educations and incomes to the adoptive American families. To isolate institutional care as the factor producing the long-term outcomes following removal from early adversity ideally one would compared poor Russian/Eastern European children who were and were not institutionalized, as Naumova and colleagues (2011) did, but then who were all removed from conditions of adversity by around two years of age and placed in low risk, high resourced families until they were adolescents. Studies like the Bucharest Early Intervention Study (e.g., Drury et al.,2012) are fairly well set up to conduct the appropriate study and it is hoped that they will be able to replicate some of the present findings. In the present study, we are not attributing the effects to institutional care, however, but rather we are assuming that everything that differed between the groups from conception until adoption may have contributed to the differences we noted. Indeed, children who are abandoned or removed from their families and placed in institutional care often have difficult prenatal histories and/or are removed from their families because of neglect, abuse, and parental incarceration (Gunnar et al., 2000). Thus, we are examining epigenetic differences between children who experienced significant early life stress and exposure to different environmental factors, such as smoke, compared to those whose early development occurred in a relatively low stress context.

Second, because we did not have blood collected at adoption to compare our findings with we cannot determine whether methylation differences during adolescence represented a change from those that would have been noted before the children spent time in their families. Longitudinal work is clearly needed. Third, the effect sizes are modest, albeit consistent with other similar work in the literature (D. Mehta et al., 2013; Naumova et al., 2011). Fourth, the sample size was limited and more participants would have provided power to detect differences in methylation at more sites even after p-value corrections. Fifth, a differential CBC was not conducted on the original blood samples, so cell types were calculated based on a published algorithm, and effect of cell type was regressed out of the data (Houseman et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2015). Since both the algorithm and the regression method have been extensively used, and our PCA analysis indicates that cell type effects were efficiently removed from our data set, we are confident in both methods. Nonetheless, it is possible that vestiges of cell type effect remain present in the data, or that important DNA methylation changes that were present only in a single cell type are being removed by our correction method. Finally, while the adopted and comparison youth were Caucasian, most of the non-adopted youth were of Nordic and European descent, while the adopted youth were of Russian/Eastern European heritage. Thus allelic differences between the groups may have influenced the results.

Despite these limitations, the results raise the possibility of differences in DNA methylation patterns as a function of early adversity that persist for years following removal from adversity and placement in supportive, well-resourced homes. However, because of the limitations noted, these findings should be considered preliminary and in need of replication.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the families and youth who participated in this study and Bonny Donzella, Tori Simenec, Natalie Ottum, and Zamzam Ahmed for their assistance with data collection. We are especially grateful to Elena Grigorenko, Oksana Naumova and their co-authors who graciously shared their data. This work was supported by funds from the Child and Brain Development Program of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research to MRG and MSK, the Interdisciplinary Training Program in Cognitive Science (T32 HD007151) to EAE, an NIMH training grant fellowship (T32MH015755) to JRD, a Mining for Miracles fellowship from the Child and Family Research Institute to MJJ and the Canada Research Chair in Social Epigenetics to MSK. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Balakathiresan NS, Chandran R, Bhomia M, Jia M, Li H, Maheshwari RK. Serum and amygdala microRNA signatures of posttraumatic stress: fear correlation and biomarker potential. Journal of Psychiatry Research. 2014;57:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition, and disease in later life. Nutrition. 1997;13:807–813. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature. 2007;447:396–398. doi: 10.1038/nature05913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghol N, Suderman M, McArdle W, Racine A, Hallett M, Pembrey M, Szyf M. Associations with early-life socio-economic position in adult DNA methylation. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;41:62–74. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornancin F. Ceramide kinase: the first decade. Cell Signal. 2011;23:999–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgon R, Gentleman R, Huber W. Independent filtering increases detection power for high-throughput experiments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2010;107:9546–9551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914005107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Kobor MS. Development and the epigenome: the 'synapse' of gene-environment interplay. Developmental Science. 2015;18:1–23. doi: 10.1111/desc.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Back SE. Childhood trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol dependence. Alcohol Research. 2012;34:408–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EA, Hostinar CE, Mliner SB, Gunnar MR. The emergence of attachment following early social deprivation. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:479–489. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chami N, Lettre G. Lessons and implications from genome-wide association studies (GWAS): Findings of blood cell phenotypes. Genes (Basel) 2014;5:51–64. doi: 10.3390/genes5010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-C, Lin C-C, Hsieh W-L, Lai H-W, Tsai C-H, Cheng Y-WM. MicroRNA expression profiling in PBMCs: a potential diagnostic biomarker of chronic hepatitis C. Disease Markers. 2014;2014:367157. doi: 10.1155/2014/367157. 367157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Grennan K, Badner J, Zhang D, Gershon E, Jin L, Liu C. Removing Batch Effects in Analysis of Expression Microarray Data: An Evaluation of Six Batch Adjustment Methods. PLos One. 2011;6:e17238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugani HT, Behen ME, Muzik O, Juhasz C, Nagy F, Chugani DC. Local brain functional activity following early deprivation: A study of postinstitutionalized Romanian orphans. NeuroImage. 2001;14:1290–1301. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Annual Research Review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children--past, present, and future perspectives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:402–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho R, Viola TW, Walss-Bass C, Brietzke E, Grassi-Oliveira R. Childhood maltreatment and inflammatory markers: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandianvia. 2014;129:180–192. doi: 10.1111/acps.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JA, Zhu X, Djajadi HR, Molday LL, Smith RS, Libby RT, John SW, Molday RS. Phospholipid flippase ATP8A2 is required for normal visual and auditory function and photoreceptor and spiral ganglion cell survival. Journal of Cell Science. 2014;127(PT 5):1138–1149. doi: 10.1242/jcs.145052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colige A, Nuytinck L, Hausser I, van Essen AJ, Thiry M, Herens C, Ades LC, Malfait F, Paepe AD, Franck P, Wolff G, Oosterwijk JC, Smitt JH, Lapiere CM, Nusgens BV. Novel types of mutation responsible for the dermatosparactic type of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (type VIIC) and common polymorphisms in the ADAMTS2 gene. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2004;123:656–663. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colige A, Ruggiero F, Vandenberghe I, Dubail J, Kesteloot F, Van Beeumen J, Beschin A, Brys L, Lapiere CM, Nusgens B. Domain and maturation processes that regulate the activity of ADAMTS-2, a metalloproteinase cleaving the aminopropeptide of fibrillar procollagens types I-III and V. Journal of Biology and Chemistry(280) 2005:34397–34408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506458200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft C, O’Connor TG, Keavene L, Groothues C, Rutter M. Longitudinal change in parenting associated with developmental delay and catch-up. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2001;42:649–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MN, Volta M, Pidsley R, Lunnon K, Dixit A, Lovestone S, Coarfa C, Harris RA, Milosavljevic A, Troakes C, et al. Functional annotation of the human brain methylome identifies tissue-specific epigenetic variation across brain and blood. Genome Biology. 2012;13:R43. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan MV, Shields B, Cutrona C, Gao L, Gibbons FX, Simons R, RA P. The effect of smoking on DNA methylation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from African American women. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:151. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury SS, Theall K, Gleason MM, Smyke AT, De Vivo I, Wong JY, Nelson CA. Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: linking early adversity and cellular aging. Molecular Psychiatry. 2012;17:719–727. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du P, Kibbe WA, Lin SM. Lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1547–1548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckerle JK, Hill LK, Iverson S, Hellerstedt W, Gunnar MR, Johnson DE. Vision and hearing deficits and associations with parent-reported behavioral and developmental problems in international adoptees. Maternal and Child Health. 2014;18:575–583. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1274-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott HR, Tillin T, McArdle WL, Ho K, Duggirala A, Frayling TM, Relton CL. Differences in smoking associated DNA methylation patterns in South Asians and Europeans. Clinical Epigenetics. 2014;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen HB, Biering-Sørensen S, Lund N, Correia C, Rodrigues A, Andersen A, Benn CS. Factors associated with thymic size at birth among low and normal birthweight infants. Journal of Pediatrics. 2014;165:713–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.06.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Boyce T, Goldstein LH, Armstrong JM, Kraemer HC, Kupfer D. The confluence of mental, physical, social and academic difficulties in middle childhood. II: Developing the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:588–603. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Boyce WT, Hertzman C, Lam LL, Armstrong JM, Neumann SM, Kobor MS. Epigenetic vestiges of early developmental adversity: Childhood stress exposure and DNA methylation in adolescence. Child Development. 2013;84:58–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré P, Jones MJ, Meaney MJ, Emberly E, Turecki G, Kobor MS. Concordant and discordant DNA methylation signatures of aging in human blood and brain. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2015;8:19. doi: 10.1186/s13072-015-0011-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felliti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP. The relationship of adult health status to childhood abuse and household dysfunction. American Journal of Preventitive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernald LC, Grantham-McGregor SM. Growth retardation is associated with changes in the stress response system and behavior in school-aged Jamaican children. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132:3674–3679. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E, De Smaele E, Miele E, Laneve P, Po A, Pelloni M, Screpanti I. Concerted microRNA control of Hedgehog signalling in cerebellar neuronal progenitor and tumour cells. Embo J. 2008;27:2616–2627. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AS, Kraemer GW, Gonzalez A, Lovic V, Rees S, Melo A. Mothering begets mothering: the transmission of behavior and its neurobiology across generations. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2002;73:61–75. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00793-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin MC, Tarullo AR, Van Ryzin M, Gunnar MR. Post-adoption parenting and socioemotional development in post-institutionalized children. Development and Psychopathology. 2012;24:35–48. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis J, Mistry M, Pavlidis P. Gene function analysis in complex data sets using ErmineJ. Nature Protocols. 2010;5:1148–1159. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnar MR, Bruce J, Grotevant HD. International adoption of institutionally reared children: Research and policy. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:677–693. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellerstedt WL, Madsen NJ, Gunnar MR, Grotevant HD, Lee RM, Johnson DE. The international adoption project: Population-based surveillance of Minnesota parents who adopted children internationally. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;12:162–171. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C. The biological embedding of early experience and its effects on health in adulthood. Annals of the New York Academy of Science. 1999;896:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C, Boyce T. How experience gets under the skin to create gradients in developmental health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:329–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodel AS, Hunt RH, Cowell RA, Van Den Heuvel SE, Gunnar MR, Thomas KM. Duration of early adversity and structural brain development in post-institutionalized adolescents. Neuroimage. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Q, Barr T, Gee L, Vickers J, Wymer J, Borsani EPA. Keratinocyte expression of calcitonin gene-related peptide β: implications for neuropathic and inflammatory pain mechanisms. Pain. 2011;152:2036–2051. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Kelsey KT. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys KL, Zeanah CH. Deviations from the expectable environment in early childhood and pmerging Psychopathology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):154–70. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth RS, Bird AP. CpG islands--'a rough guide'. FEBS Letters. 2009;583:1713–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe AE, Irizarry RA. Accounting for cellular heterogeneity is critical in epigenome-wide association studies. Genome Biology. 2014;15:R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Gunnar MR. Growth failure in In stitutionalized children. In: McCall RB, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Groark CJ, Groza VK, editors. Children without permanent parents: Research, practice, and policy. Monograph of the Society for Child Development. Vol. 76. 2011. pp. 92–126. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JH, Cutcheon S. Assessing life events in older children and adolescents: Preliminary findings with the life events checklist. In: Sarason IG, Spielberger CD, editors. Stress and Anxiety. Vol. 7. Washington, D.G: Hemisphere; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nature Review Genetics. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MJ, Islam SA, Edgar RD, Kobor MS. Adjusting for Cell Type Composition in DNA Methylation Data Using a Regression-Based Approach. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2015 doi: 10.1007/7651_2015_262. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert BR, Håberg SE, Nilsen RM, Wang X, Vollset SE, Murphy SK, London SJ. 450K epigenome-wide scan identifies differential DNA methylation in newborns related to maternal smoking during pregnancy. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120:1425–1431. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestler DC, Christensen B, Karagas MR, Marsit CJ, Langevin SM, Kelsey KT, Houseman EA. Blood-based profiles of DNA methylation predict the underlying distribution of cell types: A validation analysis. Epigenetics. 2013;8:816–826. doi: 10.4161/epi.25430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn JN, Howell BR, Guzman DB, Meyer JS, Ibegbu CC, Sanchez MM. Early life stress and perinatal glucocorticoid exposure produce complex immune system alterations, including accelerated T cell immunosenescence, in adolescent rhesus macaques. Brain, behavior and immunity. 2014;40:e50. [Google Scholar]

- Koss KJ, Hostinar CE, Donzella B, Gunnar MR. Social deprivation and the HPA axis in early development. Developmental Science. 2014;50:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta R, Kreppner J, Rutter M, Beckett C, Castle J, Stevens S, Sonuga-Barke EJ. III. Deprivation-specific psychological patterns. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child. 2010;75:48–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam LL, Emberly E, Fraser HB, Neumann SM, Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS. Factors underlying variable DNA methylation in a human community cohort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2012;109(Suppl 2):17253–17260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121249109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle P, Molet S, Janin A, Van der Heyden J, Tavernier J, Fiers W, Tonnel A-B. ESM-1 is a novel human endothelial cell-specific molecule expressed in lung and regulated by cytokines. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271:20458–20464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.34.20458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KWK, Richmond R, Hu P, French L, Shin J, Bourdon C, Gaunt T. Prenatal Exposure to Maternal Cigarette Smoking and DNA Methylation: Epigenome-Wide Association in a Discovery Sample of Adolescents and Replication in an Independent Cohort at Birth through 17 Years of Age. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2015;23:193–199. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KWK, Richmond R, Hu P, French L, Shin J, Bourdon C, Pausova Z, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Maternal Cigarette Smoking and DNA Methylation: Epigenome-Wide Association in a Discovery Sample of Adolescents and Replication in an Independent Cohort at Birth through 17 Years of Age. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2015;123(2):193–9. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KWK, Ku SK, Kim SW, Bae JS. Endocan elicits severe vascular inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo. Joural of Cellular Physiology. 2014;229:620–630. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MH, Gluck JP, Petitto JM, Hensley LL, Ozer H. Early social deprivation in nonhuman primates: long-term effects on survival and cell-mediated immunity. Biological Psychiatry. 2000:47119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Aryee MJ, Padyukov L, Fallin MD, Hesselberg E, Runarsson A, Feinberg AP. Epigenome-wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Biotechnology. 2013;31:142–147. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, Johnson AE, Westerlund A, Pollak SD, Nelson CA, Gunnar MR. The effect of early deprivation on executive attention in middle childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54:37–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loman MM, Wiik KL, Frenn KA, Pollak SD, Gunnar MR. Post-institutionalized children’s development: Growth, cognitive, and language outcomes. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:426–434. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b1fd08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubach GR, Coe CL, Ershler WB. Effects of early rearing environment on immune responses of infant rhesus monkeys. Brain, behavior and immunity. 1995;9:31–46. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1995.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Zhang Y, Ruan X, Jiang X, Zhu L, Wang X, Chen Y. Fasting-induced protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit contributes to postprandial blood glucose homeostasis via regulation of hepatic glycogenesis. Diabetes. 2011;60:1435–1445. doi: 10.2337/db10-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz PE, Turecki G. DNA methylation and childhood maltreatment: From animal models to human studies. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;264:142–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksimovic J, Gordon L, Oshlack A. SWAN: Subset-quantile within array normalization for illumina infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChips. Genome Biology. 2012;13:R44. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malnic B, Godfrey PA, Buck LB. The human olfactory receptor gene family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2004;101:2584–2589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307882100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markunas CA, Xu Z, Harlid S, Wade PA, Lie RT, Taylor JA, Wilcox AJ. Identification of DNA Methylation Changes in Newborns Related to Maternal Smoking during Pregnancy. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2014;122:1147–1153. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonté B, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nature Neuroscience. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuinness D, McGlynn LM, Johnson PC, MacIntyre A, Batty GD, Burns H, Shiels PG. Socio-economic status is associated with epigenetic differences in the pSoBid cohort. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;41:151–160. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown CR, Nowak RB, Gokhin DS, Fowler VM. Tropomyosin is required for cardiac morphogenesis, myofibril assembly, and formation of adherens junctions in the developing mouse embryo. Developmental Dynamics. 2014;243:800–817. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]