Abstract

The heterogeneity of cellular states in cancer has been linked to drug resistance, cancer progression and presence of cancer cells with properties of normal tissue stem cells1,2. Secreted Wnt signals maintain stem cells in various epithelial tissues, including in lung development and regeneration3–5. Here we report that murine and human lung adenocarcinomas display hierarchical features with two distinct subpopulations, one with high Wnt signaling activity and another forming a niche that provides the Wnt ligand. The Wnt responder cells showed increased tumour propagation ability, suggesting that they have features of normal tissue stem cells. Genetic perturbation of Wnt production or signaling suppressed tumour progression. Small molecule inhibitors targeting essential post-translational modification of Wnt reduced tumour growth and dramatically decreased proliferative potential of the lung cancer cells, leading to improved survival of tumour-bearing mice. These results indicate that strategies for disrupting pathways that maintain stem-like and niche cell phenotypes can translate into effective anti-cancer therapies.

Stem cells are defined by their capacity to self-renew while also producing differentiated cells. The decision to divide or differentiate is primarily controlled by extrinsic signaling factors, which, together with the cells that produce them, form a niche with a local range of action capable of supporting a limited number of stem cells. Among the niche signals that promote stem cell phenotypes, secreted Wnt proteins are notable due to their function in multiple epithelial stem cell compartments3. Wnt growth factors are palmitoylated in cells that produce them by the membrane-bound O-acyltransferase Porcupine (encoded by Porcn in mice)3. This postranslational modification is critical for Wnt secretion and binding to Frizzled family receptors3. Wnt binds Frizzled, promoting the stabilization, nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity of β-catenin through its interaction with T-cell factor (TCF) family transcription factors. Recently, R-spondin (Rspo) growth factors were found to amplify Wnt signaling by engaging Leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein coupled receptor (Lgr)4, Lgr5 and Lgr66. Lgr5 marks stem cells in multiple epithelial tissues and in intestinal adenomas3,6–8. Stem-like cells have recently been described in autochthonous mouse tumour models7,9,10 and in tumour transplants11–13, but evidence for the existence of stem-like cells and particularly their niche in advanced cancers in situ has been lacking14.

Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is a leading cause of death globally. Tumours driven by oncogenic KRAS account for approximately 30% of LUAD, which lacks effective chemotherapies15. Wnt signaling is essential for the initiation and maintenance of Braf-driven lung adenomas in mice16, and forced activation of the pathway promotes progression of Kras or Braf mutant lung tumours16,17. Human LUAD, in particular metastasis, is frequently associated with increased expression of Wnt pathway-activating genes and down-regulation of negative regulators of the pathway18,19.

We isolated tdTomato+ primary cancer cells from autochthonous KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) mouse LUAD, and established low-density 3-dimensional (3D) organotypic tumour spheroid cultures. 2.7% (±0.5%) of the cells gave rise to persistently proliferating spheroids (Figure 1a, b), suggesting that cells capable of self-renewal comprise a small minority. Recombinant Wnt3a, R-spondin-1, or their combination (RW) increased the absolute number and ratio of primary murine KP LUAD spheroids that contained proliferating cells, and promoted overall cell proliferation (Figure 1a, b; Extended Data Figure 1a, b). Conversely, inhibition of ligand-driven Wnt signaling with either the Porcupine inhibitor LGK974 (ref. 20), short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting Porcn or recombinant DKK-1 (a Wnt antagonist3) suppressed proliferative capacity of primary LUAD cells in 3D spheroids (Figure 1a, b; Extended Data Figure 1a-f). Tumour formation by primary LUAD cells was markedly decreased upon orthotopic transplantation (genetically engineered mouse model –derived allograft, GEMM-DA) into recipient mice that were treated with LGK974 compared to control (Figure 1c; Extended Data Figure 1g). Collectively, these data indicate that KP LUAD cells display heterogeneity in their proliferative potential, which is maintained by Wnt signals produced by the cancer cells.

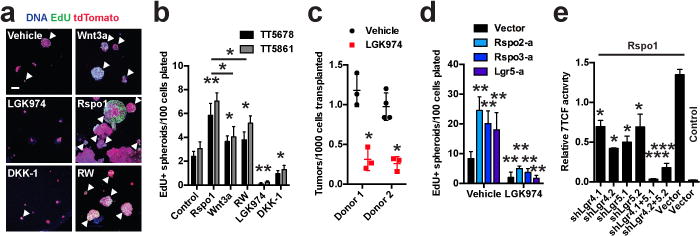

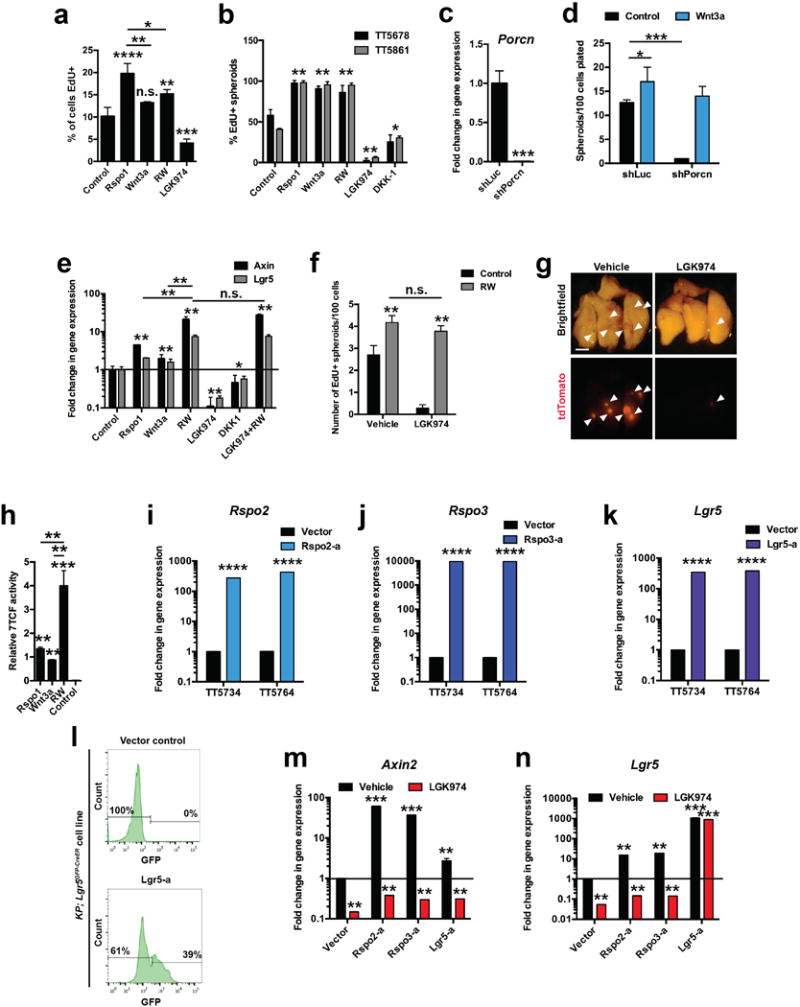

Figure 1. Ligand-dependent Wnt signaling sustains proliferative potential in lung adenocarcinoma.

a, 3D cultures of sorted tdTomato+ (red) primary mouse KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) LUAD cells 14 days after plating. Proliferating (EdU+) cells (green, arrowheads). Scale bar: 100 μm. b, Quantification of tumour spheroids containing EdU+ cells from two mice (TT5678 and TT5861). N = 8 wells/condition. c, Quantification of KPT LUAD primary transplant tumours in recipient mouse lungs treated with LGK974 or vehicle for 8 weeks. d, Quantification of tumour spheroids containing EdU+ cells 10 days after plating. Rspo2-a, Rspo3-a and Lgr5-a refer to sublines expressing CRISPR-activator (SAM) components driving expression of the indicated gene. N = 8 wells/condition. e, Wnt pathway activity measured by TOPFLASH assay in KP LUAD sublines stably expressing shRNAs targeting Lgr4, Lgr5, Lgr4+Lgr5 or a Vector control. N = 3 technical replicates/condition, experiment was repeated 4 times. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared to control, except in (d) where comparison in the LGK974 group is to the same CRISPR-activator line, and in (e) where comparison is to Rspo1 stimulation. Two-way ANOVA: (b), (d–e); Student’s t-test: (c); error bars: +SD.

Rspo1 alone was most potent in stimulating proliferation and expansion of KP LUAD spheroids (Figure 1a, b; Extended Data Figure 1a), even though, as expected, the combination of recombinant Rspo1 and Wnt3a (RW) was most potent in activating the Wnt pathway (Extended Data Figure 1e, h; Supplementary Information Text). We next employed the CRISPR/Cas9-based Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) system21 to robustly drive expression of Rspo2, Rspo3 or Lgr5 in KP LUAD cells (Extended Data Figure 1i-l); this increased their proliferation and induced Wnt target genes in 3D spheroid culture, both of which were suppressed by LGK974 (Figure 1d, Extended Data Figure 1m, n). Knockdown of both Lgr4 and Lgr5 was required to fully suppress R-spondin-driven Wnt pathway activation (Extended Data Figure 2a-g, Figure 1e), indicating that both Lgr4 and Lgr5 are R-spondin receptors in the KP LUAD model.

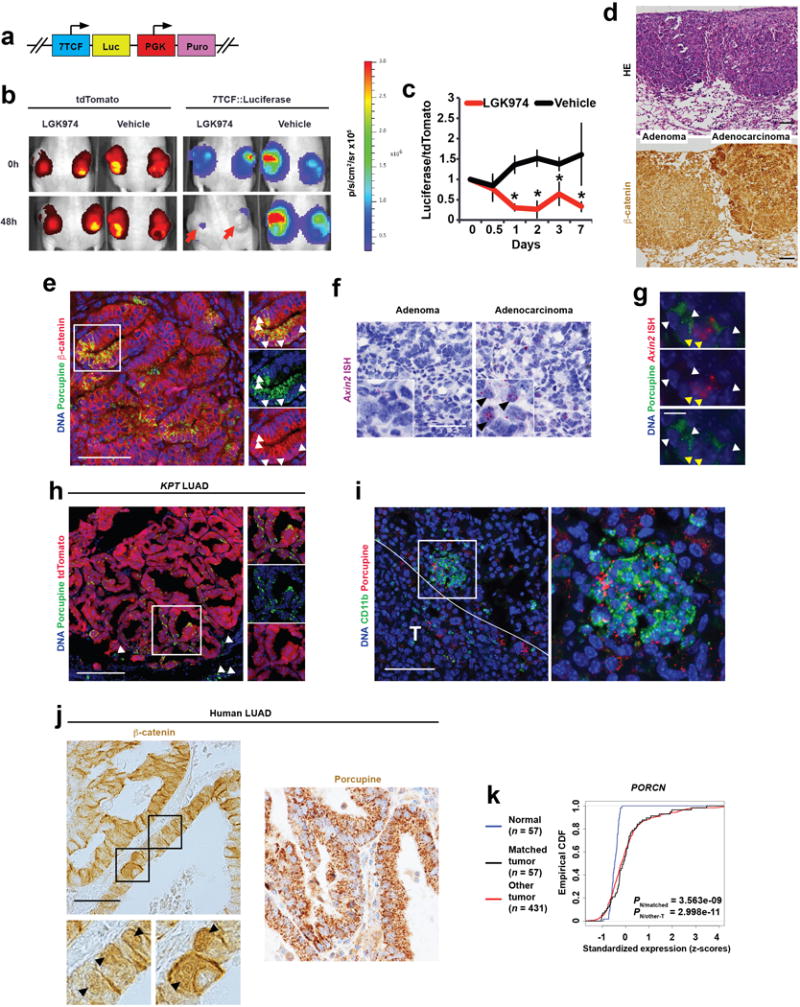

We next assessed whether the Wnt pathway is activated in autochthonous KP LUAD tumours in vivo. Using a luciferase or GFP reporter gene driven by a synthetic β-catenin-sensitive 7TCF promoter, we observed Wnt pathway activation in a subpopulation of cancer cells particularly in large autochthonous KP tumours (Figure 2a, b). In subcutaneous transplants of KP tumour lines 7TCF promoter activity was suppressed by treatment with LGK974 (Extended Data Figure 3a-c). Interestingly, we observed nuclear localization of β-catenin, a hallmark for activation of Wnt signaling, in a subpopulation of cancer cells only in tumours that had progressed from adenoma to adenocarcinoma (Figure 2c, d; Extended Data Figure 3d).

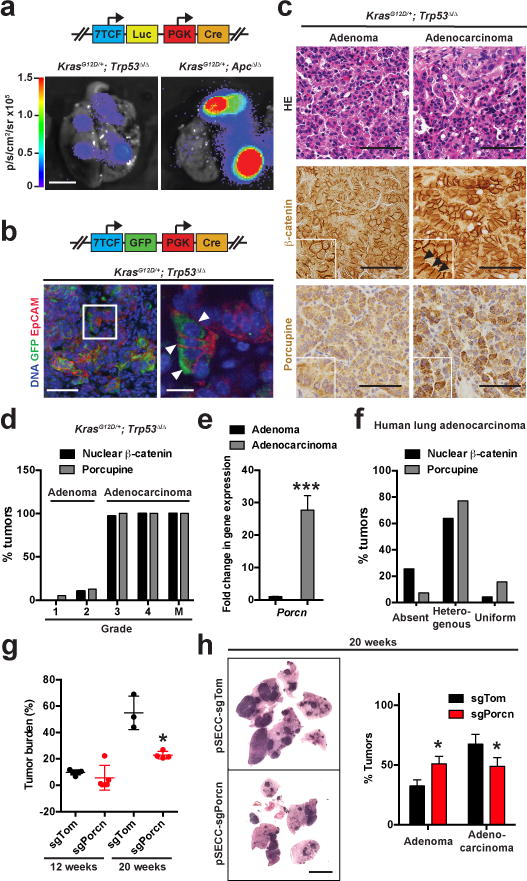

Figure 2. Porcupine+ cancer cells form a niche that drives Wnt signaling in lung adenocarcinoma.

a, Bioluminescence in lungs of KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53flox/flox (KP) or KrasLSL-G12D/+; Apcflox/flox mice 20 weeks following intratracheal infection with 7TCF::Luciferase-PGK::Cre lentivirus (see schematic). Scale bar: 5 mm. b, GFP (green) and EpCAM (red) staining in KP LUAD tumours 20 weeks following infection with 7TCF::GFP-PGK::Cre lentivirus (see schematic). Arrowheads indicate GFP+ cells with 7TCF promoter activity. Scale bars: 100 μm (left) and 10 μm (right). c, Haematoxylin-eosin (HE), β-catenin or Porcupine staining in KP adenomas or in adenocarcinomas. Note nuclear localization of β-catenin in adenocarcinomas (arrowheads). Scale bars: 100 μm. d, Percent of tumours containing subpopulations of cells with Porcupine expression or nuclear β-catenin per histological grade, or in metastases (M). N = 19 grade 1, 47 grade 2, 31 grade 3 and 11 grade 4 tumours, and 6 lymph node or thoracic wall metastases. e, Quantitative PCR analysis of Porcn gene expression in KP tumours at 9 weeks (adenomas) or 20 weeks (adenocarcinomas) post-initiation. ***P < 0.001, n = 16. f, Percent of human lung adenocarcinomas with absent, heterogenous or uniform Porcupine expression or nuclear β-catenin. N = 65. g, Quantification of tumour burden in KP mice 12 or 20 weeks following infection with 25,000 TU of pSECC-sgTom or pSECC-sgPorcn. h, Haematoxylin-eosin staining of KP LUAD-bearing lungs generated with pSECC-sgTom or pSECC-sgPorcn and quantification of the proportion of adenomas vs. adenocarcinomas at 20 weeks following tumour initiation. Scale bar: 2 mm. *P < 0.05. Student’s two-sided t-test: (e, g–h); error bars: +SD.

We next performed Porcupine immunostaining in tumour sections to identify cells competent for producing Wnt in the LUAD tumours. Interestingly, Porcupine localized to cancer cells in close proximity to cells with nuclear β-catenin or expression of the Wnt target gene Axin2 in autochthonous KP LUAD, although rare Porcupine+ macrophages were also detected, predominantly in peritumoural areas (Figure 2c, Extended Data Figure 3e-i). Furthermore, Porcn gene expression was considerably higher in adenocarcinomas compared to adenomas (Figure 2e). Importantly, we detected similar Porcupine- or nuclear β-catenin-positive subpopulations and induction of PORCN expression in human LUAD (Figure 2f, Extended Data Figure 3j, k). These findings indicate that the Wnt pathway is activated in a subpopulation of lung adenocarcinoma cells in close proximity to Porcupine+ cells that are competent for providing the Wnt signal. Porcupine localized to bronchiolar epithelium in the normal lung and was restricted to sites of high Wnt signaling and stem cell activity in the intestine and liver (Extended Data Figure 4a-e)3, suggesting that Porcupine is specifically expressed in Wnt-producing cells in normal stem cell niches.

To test the functional requirement for Porcupine expression in LUAD cells in vivo, we used CRISPR/Cas9 to inactivate Porcn specifically in the cancer cells of the KP LUAD model. Interestingly, targeting Porcn did not affect tumour grade or burden at 12 weeks after tumour initiation, when most tumours are still in the adenoma stage (Figure 2g, Extended Data Figure 5a). However, targeting Porcn reduced tumour burden and resulted in a shift to lower grade tumours at 20 weeks compared to control (Figure 2g, h). Of note, of 12 tumours graded as adenocarcinomas, 10 harbored predomidantly wild-type Porcn alleles or small non-frameshift mutations (Extended Data Figure 5b, c). In 2/12 of these tumours, where significant allelic fractions of frameshift mutations were detected, tumours still maintained residual Porcupine immunopositivity (data not shown). These data suggest that only tumours with at least a fraction of cells retaining functional Porcn were capable of progressing beyond adenomas.

Lgr5 is a Wnt target gene functionally involved in amplification of Wnt signaling and stem cell maintenance in multiple tissues3,6. When compared to adenomas, KP adenocarcinomas had an increased level of Lgr5 transcripts, which localized to a subpopulation of adenocarcinoma cells (Extended Data Figure 6a, b). Lgr4 expression in KP LUAD tumours was more widespread compared to Lgr5, much like in normal intestinal crypts6, but was enriched in the Lgr5+ cells (Extended Data Figure 6b-d). Furthermore, in GEMM-DAs established from KP LUAD tumours harboring a Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ reporter allele, the Lgr5+ cells were localized in close proximity to Porcupine+ cancer cells (Figure 3a). Sorted primary Lgr5+ KP LUAD cells were more efficient in forming persistently proliferating spheroids in vitro and orthotopic KP LUAD GEMM-DAs in vivo than the Lgr5- cells (Figure 3b; Extended Data Figure 6f, g), suggesting that these cells have high proliferative potential.

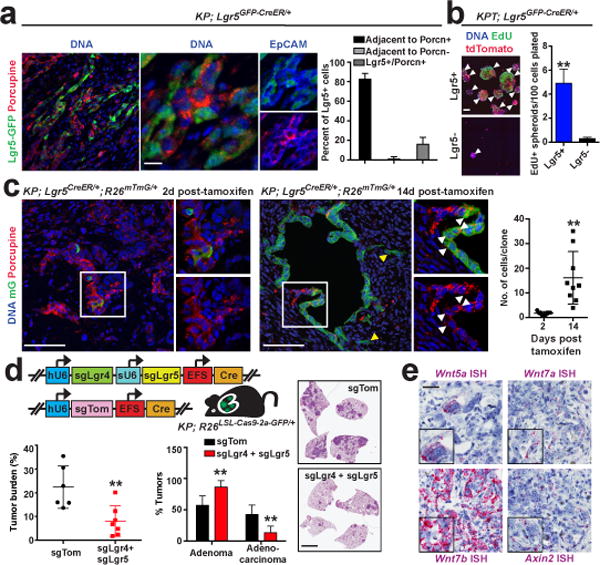

Figure 3. Lgr5+ lung adenocarcinoma cells display persistent proliferative potential.

a, Immunostaining for GFP (green), Porcupine (red), and EpCAM (blue) in a subcutaneous transplant of primary KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ LUAD cells 3 weeks following transplantation. Scale bars: 100 μm (left) and 10 μm (right). Quantification of the percent of Lgr5+ cells that are adjacent to Porcupine+ or Porcupine- cells, or that are positive for both Lgr5 and Porcupine in the transplants. N = 6 tumors. b, 3D culture of Lgr5+ and Lgr5- KP LUAD cells. Scale bar: 100 μm. Quantification of primary spheroids containing EdU+ cells (arrowheads). N = 8 wells/group. c, Lineage-tracing of of KP; Lgr5CreER/+; Rosa26LSL-mTmG/+ LUAD cells in established subcutaneous primary transplants. Note migration of individual mG positive cells (yellow arrowheads) away from clones derived from Lgr5+ cells, and Porcupine+ progeny arising from Lgr5+ cells (white arrowheads). N = 9 tumours/group. Quantification of average clone size at 2 and 14 days post-tamoxifen administration. d, Quantification of tumour burden and proportion of adenomas/adenocarcinomas, and haematoxylin-eosin staining in KP; Rosa26LSL-Cas9-2a-GFP/+ mice infected with the indicated lentiviral vectors. hU6: human U6 promoter; sU6: synthetic U6 promoter; EFS: minimal E1α promoter. N = 6 (sgTom), 7 (sgLgr + sgLgr5). Scale bar: 2 mm. e, mRNA ISH for the indicated transcripts (purple) in consecutive sections of a similar region of a KP lung adenocarcinoma. Scale bar: 100 μm. Student’s two-sided t-test: (a–d); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; error bars: ±SD.

To investigate whether the Lgr5+ cells also display stem-like properties in situ in established tumours, we established subcutaneous KP LUAD GEMM-DAs harboring Lgr5CreER and Rosa26mTmG alleles, which allowed for inducible labeling of the Lgr5+ lineage in established tumours with membrane-associated GFP (mG) using tamoxifen. Single mG+ cells were found labeled 2 days after the tamoxifen pulse in Porcupine+ niches, whereas significant expansion of the Lgr5+ clones was observed at 14 days post-tamoxifen administration (Figure 3c). The absolute number of clones did not change significantly over time (Extended Data Figure 6h). Importantly, the Lgr5+ cells gave rise to Porcupine+ cells during the 14-day chase (Figure 3c), indicating that the Lgr5+ stem-like cells can give rise to their own niche in KP LUAD. Notably, single-cell clones derived from KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ mouse LUAD formed heterogenous tumours comprised of Lgr5+, Porcupine+ and Lgr5−/Porcupine- subpopulations (Extended Data Figure 7a, b), indicating that considerable plasticity and heterogeneity in cellular states exists in the KP lung tumours11. Based on our lineage-tracing data, this heterogeneity is in part driven by cooperation between the Porcupine+ and Lgr5+ subpopulations.

Interestingly, a subpopulation of Wnt pathway-positive cells harboring stem-like properties was recently described in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cell lines12. In keeping with these findings, we detected Porcupine+ cells in close proximity to a subpopulation of Lgr5+ cells, which had increased proliferative potential in a PDAC GEMM (Extended Data Figure 7c-f). Furthermore, Lgr5+ stem-like cells have been described in intestinal adenomas7. We detected Porcupine+ cells in close proximity to the Lgr5+ cells in ApcΔ/Δ;Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ murine intestinal adenomas and Porcupine expression in human colorectal carcinomas (Extended Data Figure 7g, h). These results suggest that paracrine Wnt signals may maintain subpopulations of cancer cells in a stem-like state in other epithelial cancers.

To explore the relevance of elevated Wnt signaling in human non-small cell lung cancer, we examined gene expression patterns in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset. A ligand-stimulated Wnt gene expression signature22 correlated with poor survival and higher tumour grade, and was independently prognostic in human LUAD, but not in squamous cell lung cancer (Extended Data Figure 8a-c; Supplementary Data Table 1). We then extended this analysis to 34 additional human cancers within the TCGA dataset, and found similar correlations in PDAC and in mesothelioma (Extended Data Figure 8d, e).

Given that KP LUAD cells respond to R-spondins via Lgr4 and Lgr5, we investigated the requirement for these genes in the KP model. CRISPR/Cas9-based combined inactivation of Lgr4 and Lgr5 in the KP model led to reduced lung tumour burden and a block in progression of adenomas to adenocarcinomas (Figure 3d), similar to what was observed when targeting Porcn (Figure 2g). Tumours that progressed into adenocarcinomas harbored predomidantly wild-type alleles or small non-frameshift mutations in Lgr4 and Lgr5 (Extended Data Figure 8f-h). These data are consistent with a key role for Lgr4 and Lgr5 in the progression into adenocarcinomas. We detected expression of the Lgr4/Lgr5 ligands Rspo1 and Rspo3 in KP LUAD, which localized predominantly to endothelial cells in the tumours (Extended Data Figure 9a, b). Analogously, endothelial cells expressing R-spondin form a part of the niche for liver stem cells23.

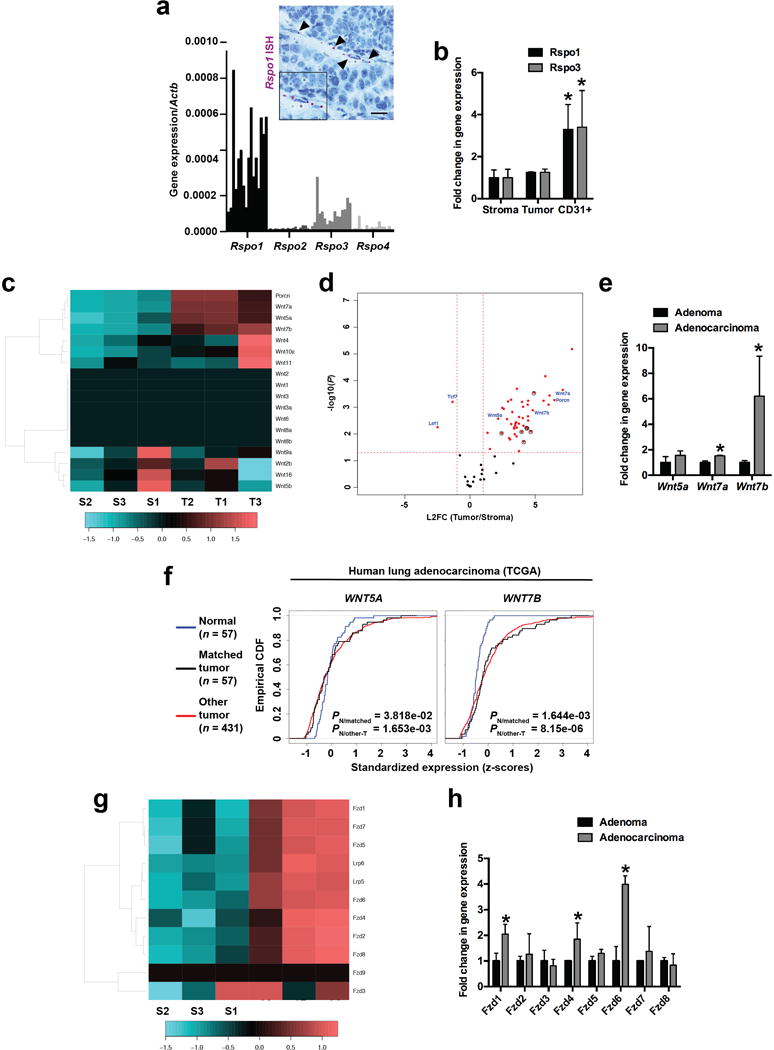

To identify the Wnt ligands and their Frizzled receptors involved in LUAD, we performed qPCR on 84 Wnt pathway-related genes in sorted KPT lung adenocarcinoma cells (T) and their stroma (S). This analysis revealed very little expression of Porcn or Wnt ligands in the stroma, consistent with the cancer cells being the predominant source of Wnt ligands in LUAD (Extended Data Figure 9c, d; Supplementary Data Table 2). Out of the 19 Wnt genes, Wnt7a, Wnt5a and Wnt7b were robustly expressed in LUAD (Extended Data Figure 9c-e). In situ hybridization placed expression of these three Wnt ligands in KP LUAD into regions with Wnt pathway activation (Figure 3e). Increased levels of WNT5A, WNT3, WNT5B, and WNT10A in subpopulations of patients and, in particular, WNT7B were observed in human LUAD when compared to normal lung in the TCGA dataset (Extended Data Figure 9f, Supplementary Data Table 3). We detected robust expression of 8 of the 10 Fzd receptors and their Lrp5 and Lrp6 co-receptors in sorted KP LUAD cells (Extended Data Figure 9g). Expression of Fzd1, Fzd4 and Fzd6 was increased in KP lung adenocarcinomas when compared to adenomas (Extended Data Figure 9h). Of note, each of these receptors can be engaged by at least one of the three Wnt ligands identified in the study24.

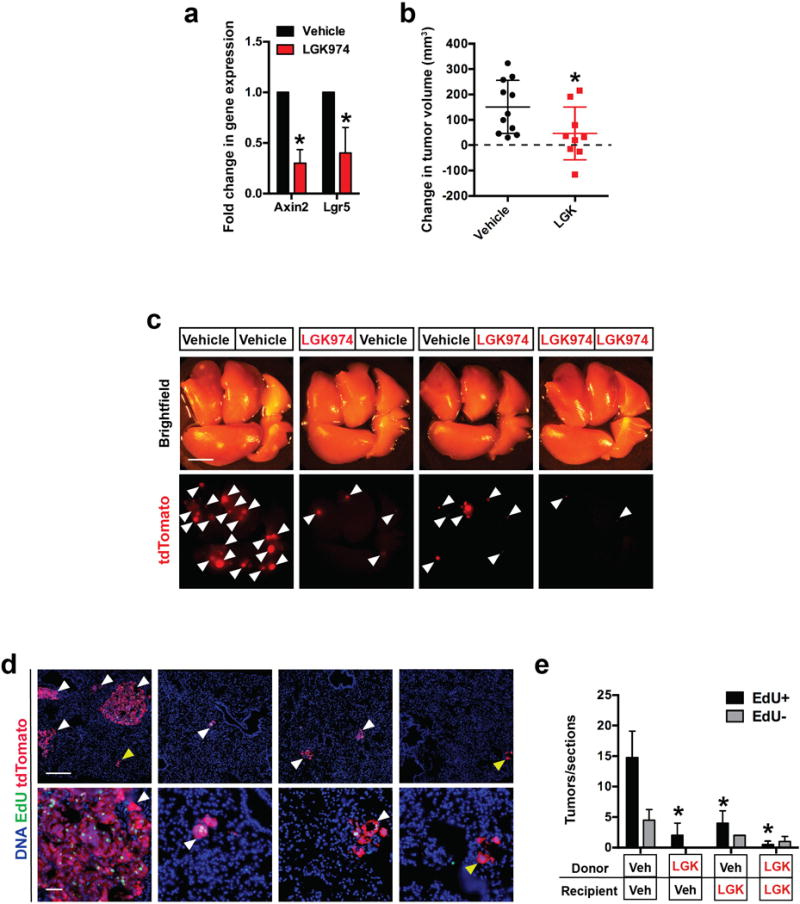

We next explored inhibition of ligand-dependent Wnt signaling as a potential therapeutic strategy in LUAD. Treatment with LGK974 suppressed Wnt target genes, inhibited tumour growth, proliferation and prolonged survival of mice with advanced autochthonous KP LUAD tumours (Figure 4a-d; Extended Data Figure 10a, b). Furthermore, treatment of tumour donor mice with LGK974 dramatically suppressed tumour-forming ability of transplanted cells and reduced numbers of proliferative tumours in recipient mice (Figure 4e; Extended Data Figure 10c-e), suggesting that inhibiting Wnt can disrupt stem-like cells in LUAD (Figure 4f).

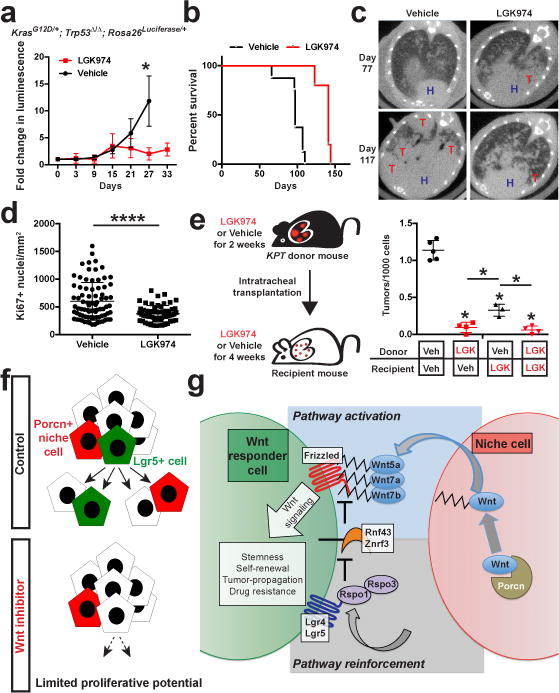

Figure 4. Porcupine inhibition improves survival by suppressing proliferative potential in mice harboring lung adenocarcinoma.

a, Fold change in bioluminescence signal in autochthonous KP LUAD tumours harboring a Rosa26Luciferase/+ allele in mice treated with LGK974 or vehicle. N = 3. b, Survival of mice harboring autochthonous KP LUAD tumours treated with LGK974 or vehicle starting at 77 days following tumour initiation. P = 0.0008; n = 5 (LGK974), 8 (Vehicle). c, Lung μCT images of mice treated with vehicle or LGK974 at 77 days after tumour initiation and after 40 days on therapy (Day 117). H: heart, T: tumour. d, Quantification of proliferating (Ki67+) cells in autochthonous KP LUAD tumours 2 weeks following treatment with LGK974 or vehicle. ****P < 0.0001; n = 80 vehicle tumours, n = 59 LGK974 tumours. e, Quantification of the number of tdTomato+ surface tumours in recipient mice. Student’s two-sided t-test: (a), (b), (d); two-way ANOVA: (e); error bars: ±SD. f, The outcome of Wnt inhibition in LUAD: Porcupine+ niche cells provide Wnt to Lgr5+ cells with robust proliferative potential, which can be suppressed by Wnt inhibitors. g, The niche for Wnt responder cells in LUAD: Lgr5+ cells (green) reside next to Porcupine+ cells (red). Wnt5a, Wnt7a and Wnt7b, provided by Porcupine+ niche cells (red), bind Frizzled on Wnt responder cells. Rspo1 and Rspo3, which bind Lgr4 and Lgr5, reinforce Wnt signaling by inhibiting Rnf43 and Znrf3 ubiquitin ligases that degrade Frizzled6. Wnt is palmitoylated (serrated line) by Porcupine, critical for Wnt secretion and binding to Frizzled3.

Our results indicate that a subset of Kras and p53 mutant LUAD cells acts as a Wnt-producing niche for another cancer cell subpopulation that responds to the Wnt signal and has robust proliferative potential (Figure 4g). Inhibiting Porcupine disrupts Wnt secretion and activity in the niche, suppressing stem cell function in tumours, which ultimately translates into therapeutic benefit (Figure 4f). Inhibitors of Wnt signaling or the Rspo-Lgr5 axis have shown efficacy also in patient-derived xenograft models of LUAD25,26. We identified specific components of the Wnt–Frizzled and R-spondin–Lgr5 signaling pathways that may serve as entry points for therapeutic approaches aimed at disrupting the interactions between niche cells and stem-like cells in LUAD (Figure 4g).

In this study, we observed the emergence of Porcupine+ niche cells and Lgr5+ stem-like cells as KP lung adenomas progress to adenocarcinomas. This transition is also associated with amplification of the mutant KrasG12D locus and consequent increase in mitogen-activated protein kinase activity as well as upregulation of tissue repair pathways27. Therefore increased proliferation and activation of regenerative pathways may contribute to activation of Wnt signaling in adenocarcinoma. Interestingly, heterogeneous Wnt pathway activation and Lgr5+ expression in progenitor-like cells is also observed during repair of normal epithelial tissues8, suggesting that lung adenocarcinomas may be co-opting a latent tissue regenerative program upon progression. Our results indicate that Wnt pathway activity in a subset of cancer cells is essential for the maintenance of proliferative potential in LUAD, which presents a novel therapeutic opportunity for the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma and other epithelial cancers.

Methods

Mice

Previously published KrasLSL-G12D (ref. 28), Trp53flox/flox (ref. 29), KrasFSF-G12D (ref. 30), Trp53frt/frt (ref. 31), Rosa26LSL-tdTomato (ref. 32), Apcflox/flox (ref. 33), Rosa26LSL-Luciferase (ref. 34), Rosa26mTmG (ref. 35), Lgr5GFP-IRES-CreER/+ (ref. 36), and Lgr5CreER/+ (ref. 8) gene-targeted mice were used in the study. All mice were maintained in a mixed Sv129/C57 black 6 genetic background. Tumours were induced in KP mice with 2.5×107 plaque-forming units (pfu) of AdCMV-Cre (Iowa), 2×108 pfu of AdSPC-Cre23,37, 1×108 pfu of AdCMV-FlpO (Iowa) or 15-50,000 transforming units of lentiviral Cre, as previously described38,39, in mice that were between 8-12 weeks of age. Approximately equal numbers of male and female mice were included in all experimental groups in all mouse experiments. Mice bearing lung tumours were treated with 10 mg/kg/d of LGK974 (ref. 20) resuspended in 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose (Sigma) and 0.5% Tween 80 (Sigma) or vehicle. Weights of mice were followed weekly. The growth of autochthonous KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26Luciferase/+ lung tumors was followed longitudinally by bioluminescence imaging, as before34. Briefly, mice were anesthesized by isoflurane inhalation, administered 100 mg/kg D-Luciferin (Perkin Elmer) by intraperitoneal injection and imaged 10 min after using the IVIS imaging system (Perkin Elmer). Such longitudinal imaging experiments were repeated three times and representative data from one such experiment is shown in Figure 4a. Survival experiments were repeated three times and representative data from one such experiment is shown in Figure 4b. For survival experiments, mice were randomized based on their tumour burden as assessed by μCT. Mice were assigned a tumor burden score ranging from 0 (no tumors) to 10 (lungs completely full of tumors), and experimental groups were formed such that each group had approximately equal tumor average tumor burdens. Mice with tumor burden scores under 3 were excluded from the study. The health of the mice in all experiments was monitored daily by the investigators and/or veterinary staff at the Department of Comparative Medicine at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Mice with a body condition score under 2 were humanely euthanised. Animal studies were approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Committee for Animal Care (institutional animal welfare assurance no. A-3125-01). The maximal tumour dimensions permitted by the MIT Committee for Animal Care were 2 cm across the largest tumour diameter and this limit was not reached in any experiments.

Isolation of primary mouse lung adenocarcinoma cells

Mice bearing KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) or KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+(KPT; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+) LUAD tumours or were euthanized 12-26 weeks following tumour induction and perfused with S-MEM (Gibco) through the right ventricle of the heart. Dissected lungs with tumours were dissociated in protease and DNAse solution of the Lung Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) followed by mechanical dissociation using MACS “C” columns (Miltenyi Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The dissociate was filtered using a 100 μm strainer and red blood cells were lysed using ACK (Thermo), followed by staining with APC-conjugated CD31 (Biolegend, cat. # 102510), CD45 (BD, cat. # 559864), CD11b (eBioscience, cat. # 17-0112-82), and TER119 (BD, cat. # 557909) antibodies and dead cells with DAPI (Sigma). The same approach using the Tumour Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotech) was used to isolate KPT; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+; Pdx1::Cre PDAC tumours cells when mice were 7 weeks of age.

Fluorescence-assisted cell sorting (FACS) of stained primary cells was performed using a FACSAria sorter (BD) by gating for tdTomato+/DAPI−/APC− cells (total cancer cell fraction) in the case of KPT tumours. In the case of KPT; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ tumours, both tdTomato+/DAPI−/APC−/GFP+ (Lgr5+ cancer cell fraction) and tdTomato+/DAPI−/APC− /GFP− (Lgr5- cancer cell fraction) populations were sorted. Sorted cells were placed in 3-dimensional organotypic culture, transplanted intratracheally into NOD-SCID-gamma (NSG) recipient mice, or subcutaneously into athymic nu/nu mice immediately after sorting (see below).

Transplantation of cancer cells into recipient mice

For intratracheal transplantation, 8-10 weeks old immunodeficient NSG mice were anesthesized, intubated as previously described38, and allowed to inhale 15-50,000 primary sorted KP LUAD cancer cells resuspended in 30 μl of S-MEM (Gibco). For subcutaneous transplantation, 50-500,000 primary sorted KP LUAD cells, KP LUAD cell lines or single-cell clones derived from a KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ LUAD cell line were resuspended in 50% Matrigel/50% S-MEM and injected subcutaneously into both flanks of athymic nu/nu mice in a volume of 100 μl. Mice harboring transplant tumours were injected intraperitoneally with 1 mg of 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU, Setareh Biotech) 4 hours prior to euthanasia to label proliferating cells. EdU was detected in cryosections using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Thermo) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Lgr5+ cells in close proximity to Porcupine were detected by GFP and Porcupine immunofluorescence: All GFP+ cells were analysed as being immediately adjacent to at least one Porcupine+ cell, as double-positive for both GFP and Porcupine, or as neither of the above (Figure 3a). All transplantation experiments were reproduced three times.

Low-density 3-dimensional organotypic cell culture

150-1000 KP primary mouse LUAD cells, cells from established KP LUAD cell lines, or primary mouse PDAC cells were mixed in 50% Matrigel (BD) and 50% Advanced DMEM/F12 (Gibco) and plated on 10 μl of Matrigel. The gel was allowed to solidify in 37° C, followed by addition of Advanced DMEM/F12 (Thermo) supplemented with gentamicin (Thermo), penicillin-streptomycin (VWR), 10 mM HEPES (Thermo), and 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. For Wnt pathway manipulation, cultures were incubated with 1 μg/ml recombinant mouse (rm)R-spondin1 (Sino Biological), 100 ng/ml rmWnt3a (R&D Sytstems), 500 ng/ml or 1 μg/ml rmDKK-1 (R&D Systems), or 100 nM LGK974 (Medchem Express) for 6-14 days. Media was changed every 2 days. At the end of the experiment, proliferating cells were labeled with 10 μM EdU for 4h, followed by paraformaldehyde fixation and fluorescent labeling of proliferating cells using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Imaging Kit (Thermo), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, in whole mount preparations of tumour spheroids. Proliferating spheroids were quantified using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope: a spheroid was classified as a cluster of at least 10 cells, and a proliferating spheroid contained at least one EdU positive nucleus (proliferating cells were not observed in clusters of cells smaller than 10 cells). At least four replicate wells per condition were quantified in each experiment. Images were acquired using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope. Stimulation and inhibitor experiments were reproduced at least 10 times for each experimental condition.

Cell lines

Multiple cell lines were established from the mouse LUAD and PDAC KP GEMMs over the course of the study. The cell lines have not been authenticated. The cell lines were routinely tested for Mycoplasma and found to be negative. At the time of conducting the experiments, no cell lines used were found to be listed in the ICLAC database of misidentified cell lines.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues or tumour organoids were fixed in 10% formalin overnight and embedded in paraffin. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on a Thermo Autostainer 360 with or without hematoxylin counterstaining using antibodies to β-catenin (BD, cat. # 610153), Ki67 (Vector Labs, cat. # VP-RM04), glutamine synthetase (BD, cat. # 610517), or Porcupine (AbCam, cat. # ab105543). Lungs from at least three tumor-bearing mice were analysed by each antibody. Livers and small intestines harvested from three normal, healthy mice were subjected to β-catenin, glutamine synthetase, and Porcupine IHC. 65 human LUAD tumors samples in two separate tissue microarrays were analysed by β-catenin and Porcupine IHC. 5 human colorectal adenocarcinoma samples were stained with Porcupine antibodies. All human tissue material was obtained commercially from Janssen Pharmaceuticals.

Tissue immunofluorescence

Mice were anesthetized and perfused through the right cardiac ventricle with 1% paraformaldehyde. Lungs with tumours were dissected, immersed in 4% PFA overnight and frozen in OCT medium (Sakura Finetek). 7 μm sections were stained with antibodies to EpCAM (eBioscience, cat. # 17-5791-82), β-catenin (BD, cat. # 610153), GFP (Cell Signaling Technologies, cat. # 2956S; or Aves Labs, cat. # GFP-1020), CD11b (eBioscience, cat. # 17-0112-82), or Porcupine (AbCam, cat. # ab105543). Lungs from at least three tumor-bearing mice were analysed by each antibody.

Quantification of cell proliferation in tumors

Digitally scanned images of Ki67-stained slides were created with the Aperio ScanScope AT2 at 20X magnification. Aperio’s WebScope software was used to assess for Ki67+ density per tumor area. A built-in IHC Nuclear Image Analysis algorithm was used to classify cells based on the intensity of the nuclear Ki67 stain. Nuclei were classified from 0 to 3+; only nuclei of moderate nuclear staining (2+) or intense nuclear staining (3+) were considered Ki67 positive. Tumor regions were outlined on WebScope before running the IHC Nuclear Image Analysis algorithm such that the number of 2+ and 3+ cells was normalized to tumor area.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from tumours or cells using the RNeasy plus kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using the SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo). qPCR was performed in triplicates with 2 μl of diluted cDNA (1:10) using PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix (Thermo) on a Bio-Rad iCycler RT–PCR detection system. Expression was normalized to Actb or Gapdh. All oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Supplementary Data Table 4. All qPCR experiments were reproduced using at least three biological replicates.

Alternatively, a Mouse WNT Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen) was used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Raw expression values were thresholded to drop non-detected and lowly expressed genes (maximum Ct value set to 33; 0 values set to 33). Array position to gene-name mapping details were retrieved from the manufacturer’s website (www.pcrdataanalysis.sabiosciences.com). Expression values for all genes per array were normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene Gusb. Three replicates of stroma samples and three replicates of tumour samples were compared to calculate log2 fold-change and differential expression significance values (2-sided t-test).

Lentiviral shRNA-mediated gene silencing

Short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) were cloned into lentiviral pLKO.1 vectors (Addgene #10878) or into pTRIPZ (Dharmacon) vectors and lentivirus were produced as previously described40. KP mouse LUAD cell lines were infected with the lentiviral vectors, followed by puromycin selection and, in the case cells infected with the TRIPZ virus, incubation in 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 4 days and RNA extraction for testing target knockdown (Extended Data Figure 2a and not shown). For combination Lgr4 and Lgr5 silencing experiments, cell lines expressing pLKO.1 driving Lgr4 or Lgr5 shRNAs were generated by puromycin selection, followed by infection with TRIPZ vectors driving miR30-based Lgr4 or Lgr5 shRNAs and turboRFP under the control of a TET-responsive promoter. Cells were incubated in 1 μg/ml doxycycline for 2 days and red fluorescent cells were sorted to generate pure cell lines expressing combinations of Lgr4 and Lgr5 shRNAs. All shRNA experiments were reproduced using at least three independent cell lines.

Topflash assay

10,000 of KP LUAD cells were plated in 100 μl of media containing 10% FBS per well of a white-walled 96-well plate (Perkin Elmer). After 24 h, KP mouse LUAD cells were transfected using Attractene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions with 150 ng of TOPFLASH Firefly (M50) reporter41 (Addgene #12456) and 20 ng of pRL-SV40P Renilla (Addgene #27163) constructs. In initial experiments, the Wnt-insensitive FOPFLASH Firefly (M51) reporter41 (Addgene #12457) was used to rule out signal background (not shown). Cells were stimulated for 16h with recombinant Rspo1 (1 μg/ml, Sino Biological), recombinant Wnt3a (100 ng/ml, R&D Systems) or their combination (RW) in Advanced DMEM/F12 (Gibco), with supplements listed above. After stimulation, Firefly and Renilla signals were detected using Dual-Glo luciferase detection reagents (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. A Tecan Infiniti 200 Pro plate reader and automated injector system was used to detect luminescence. To control for transfection efficiency, Firefly luciferase levels were normalized to Renilla luciferase levels to generate the measure of relative luciferase units. Experimental data are presented as mean ± s.d. from three independent wells. All TOPFLASH experiments were reproduced using at least three independent cell lines.

Application of the Synergistic Activation Mediator system to overexpress components of the Rspo-Lgr5 axis

Catalytically-dead Cas9 (dCas9)-based systems have recently emerged as powerful tools for transcriptionally activating endogenous genes42. Notably, these systems allow for overexpression of genes in their endogenous genomic context. To overexpress Rspo2, Rspo3 or Lgr5 in KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ LUAD cell lines, we employed the Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) system, which is a 3-component system based on (1) a dCas9 fusion to the transcriptional activator VP64 (a tandem repeat of four DALDDFDLDML sequences from Herpes simplex viral protein 16, VP16), (2) a modified gRNA scaffold containing two MS2 RNA aptamers, and (3) the MS2-P65-HSF1 tripartite synthetic transcriptional activator21. In this scenario, sgRNA-dependent recruitment of dCas9-VP64 and MS2-P65-HSF1 to the endogenous Rspo2, Rspo3 or Lgr5 loci results in potent transcriptional activation (Extended Data Figure 1i-l).

Non-clonal KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ or KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ LUAD cells stably expressing dCas9-VP64-Blast (Addgene #61425) and MS2-P65-HSF1-Hygro (Addgene #61426) were generated via sequential lentiviral transduction and selection with blasticidin and hygromycin, respectively. To overexpress Rspo2 or Rspo3 we designed four independent sgRNA sequences targeting the Rspo2 or Rspo3 transcription start site; sgRNAs targeting the upstream region of the Lgr5 gene were provided by L. Gilbert, M. Horlbeck and J. Weissman43. The sgRNAs were cloned into a lentiviral vector (Lenti-sgRNA-MS2-Zeocin; Addgene #61427) and subsequently transduced and zeocin-selected the aforementioned cell lines to generate KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ LUAD cell lines stably expressing all three components. These experiments were reproduced using three independent cell lines.

Cloning of lentiviral vectors

The 7TCF::Luciferase-PGK::Cre, 7TCF::GFP-PGK-Cre and U6::sgRNA-EFS::Cre (pUSEC) lentivirus vectors were generated by Gibson assembly44,45. Briefly, a 1.8 kb part corresponding to 7TCF::Luciferase or a 1.2 kb part corresponding to 7TCF::GFP were amplified from 7TFP (Addgene #24308, ref. 46) or 7TGP (Addgene #24305, ref. 46) respectively, and fused with a 0.5 kb PGK promoter part, a 1.0kb Cre cDNA part and the PmeI + BsrGI linearized LV1-5 (Addgene #68411) part44. U6::sgRNA-EFS::Cre was generated by amplifying a 2.2 kb part corresponding to U6-filler-chimeric gRNA backbone from pSECC (Addgene #60820), and fused with a 0.25 kb EFS promoter part, a 1.0kb Cre cDNA part and the PmeI + BsrGI -linearized LV1-5 (Addgene #68411) part44. Lentivirus was produced in 293FS* cells, as previously described38. Experiments utilizing 7TCF::Luciferase-PGK::Cre (Figure 2a) were reproduced twice (n = 15 mice in total) and experiments utilizing 7TCF::GFP-PGK-Cre (Figure 2b) three times (n = 19 mice in total).

For generation of lentiviruses harboring sgRNAs, three sgRNAs per gene targeting Porcn, Lgr4 or Lgr5 were designed using CRISPR Design47, cloned into pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (pX458, Addgene #48138) as previously described48, transfected into GG cells49, and screened for efficiency by Western blotting for Porcn protein or by massively parallel sequencing of the regions in Lgr4 or Lgr5 targeted by the respective sgRNAs (data not shown). The most efficient Porcn sgRNA was cloned into pSECC as previously described49. The most efficient Lgr4 and Lgr5 sgRNAs were cloned into the pUSEC vector together with a synthetic mouse/human U6 promoter (sU6), as previously described50, to generate U6::sgLgr4-sU6::Lgr5-EFS::Cre (pU2SEC).

Measurement of Wnt signaling pathway activity in tumours in vivo

A KPT LUAD cell line was transduced with 7TCF::Luciferase-PGK::Puro (7TFP) lentiviruses46, selected for puromycin resistance, and transplanted subcutaneously into flanks of immunodeficient athymic nu/nu mice. Three weeks following transplantation tumour burden was measured by registering tdTomato fluorescence using an IVIS imaging system (Perkin Elmer), followed by administration of 100 mg/kg D-Luciferin (Perkin Elmer) and registration of luciferase signal (7TCF promoter activity). The luciferase signal was normalized to the tdTomato signal (Wnt pathway activity/total tumour burden). Quantification of Wnt pathway activity was performed every 24h for a week in mice treated with 10 mg/kg/d of LGK974 or vehicle. The maximal tumour dimensions permitted by the MIT IACUC were 2 cm across the largest tumour diameter and this limit was not reached in these experiments. This experiment was reproduced twice.

Single-molecule mRNA in situ hybridization

Single-molecule in situ hybridization was performed on formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tissues using the Advanced Cell Diagnostics RNAscope 2.5 HD Detection Kit (cat. # 322360). Catalog numbers of the probes are 400331 (Axin2), 312171 (Lgr5), and 404971 (Porcn). Lungs from three tumor-bearing mice were analyzed.

Lineage-tracing of Lgr5+ cells in KP tumours

We generated KrasFSF-G12D/+; Trp53frt/frt; Lgr5CreER/+; Rosa26mTmG/+ mice and induced lung tumours by intratracheal administration of AdCMV-FlpO. Lung tumours were harvested, enzymatically dissociated and passaged in vitro for 8-10 passages to eradicate stromal cells from the cultures. Such early-passage cell lines were transplanted subcutaneously into flanks of NSG mice. When mice developed palpable tumours, they were administered a single tamoxifen pulse (20 mg/kg), or corn oil vehicle control. Tumours were harvested at 2 days or 14 days post-tamoxifen administration and prepared for cryosectioning. Three sections 500 μm apart were prepared from each tumour and imaged under a fluorescence microscope. The number of GFP+ cells per section was quantified in 9 tumors per time point.

μCT data acquisition and analysis

An eXplore CT 120 microcomputed tomography (μCT) system (Northridge Tri-Modality Imaging Inc.) was used for in vivo imaging. Mice were imaged under anesthesia (induced at 3% isoflurane in oxygen, maintained at between 2-2.5% during imaging) in groups of 4 in a custom mouse holder. Scanner settings were are follows: 720 views, 360 degree rotation, 70 kVp, 50 mA, 32 ms integration time with 2x2 detector pixel binning (isotropic nominal resolution of 50 microns). Data were reconstructed using the Parallax Innovations GPU accelerated reconstruction engine for the eXplore CT120.

Tissue density values (in Hounsfield Units, HU) for normal, air-filled lung parenchyma were determined by eye using MicroView software (Parallax Innovations). For the scanning conditions in this study a range of −550 to −300 HU was determined to represent the range of normal lung parenchyma values. A custom analysis script was created using Matlab (The Mathworks) to identify a region of interest (ROI) including the soft tissue of the mouse thorax. Within this region the volume of tissue within the “healthy” density range was measured. Within this same volume Minimum Intensity Projections (MinP) were created, both to confirm the accuracy of the ROI and to qualitatively assess lung pathology. For data visualization, the change in healthy lung volume was inverted to represent change in tumour volume (Extended Data Figure 10b). One experiment involving 9 mice treated with LGK974 and 11 mice treated with Vehicle control was carried out to track changes in tumor volume (Extended Data Figure 10b).

Human clinical data analyses

RNA-seq gene expression profiles of primary tumours and relevant clinical data of 488 lung adenocarcinoma patients were obtained from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA LUAD; http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). The Willert et al.22 Wnt signaling geneset (24 genes up-regulated after stimulation with recombinant human WNT3A) was obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)51 and used to score individual patient expression profiles using ssGSEA52,53. Patients were stratified according to their correlation score, into top (n=115) and bottom (n=114) 20th percentile sets. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was conducted between these sets of patients and the log-rank test was used to assess significance. Subsequently, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis methodology was extended to assess significant survival differences across 35 TCGA cancer types using a similar strategy.

Additionally, the Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to analyse the prognostic value of the Willert geneset across all patients within the TCGA LUAD cohort, in the context of additional clinical covariates. All univariate and multivariable analyses were conducted within a 5-year survival timeframe. The following patient and tumour-stage clinical characteristics were used: Signature (Willert et al. signature strong vs. weak correlation); Gender (male vs. female); Age (years, continuous); Smoking History (reformed > 15yrs vs. non-smoker, reformed < 15yrs vs. non-smoker, current smoker vs. non-smoker); Mutational Load (derived as the number of non-silent mutations per 30Mb of coding sequence, continuous); Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM Stage specification (Stage III/IV vs. I/II); UICC T score specification (T2 vs. T1, T3/T4 vs. T1); UICC N score specification (N1/N2 vs. N0). Hazard ratio proportionality assumptions for the Cox regression model were validated by testing for all interactions simultaneously (p = 0.703). Interaction between the Willert-signature and TNM stage, T score, and N score (significant covariates in the model) were tested using a likelihood ratio test (LRT) to contrast a model consisting of both covariates with another model consisting of both covariates plus an interaction term. No statistically significant difference was found between the two models (TNM: p=0.8751, T score: p=0.8204, N score: p=0.8625; likelihood ratio test). To test for statistically significant differences between Willert signature correlation scores across TCGA LUAD grade levels (T-scores), the Kurskal-Wallis test was used to assess overall significance and the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was used to assess pairwise differences. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (www.R-project.org) and all survival analyses and were conducted using the survival package in R.

Finally, we analysed the expression of Wnt pathway genes present in the Mouse WNT Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen) in human TCGA LUAD data (Supplementary Data Table 3). Expression levels between 57 LUAD tumour samples and corresponding matched normal samples were analysed using empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) plots. Significance of different expression levels was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test. For a more comprehensive analysis covering human orthologs of all WNT pathway genes tested on the mouse qPCR array, pairwise differential expression analysis (tumour versus normal, n=57 each) was performed using EBSeq v1.4.0 (ref. 54)

Massively parallel sequencing

Genomic regions containing the sgPorcn, sgLgr4 or sgLgr5 target sequences were amplified using Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerase and gel purified (primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Data Table 4). Sequencing libraries were prepared from 50 ng of PCR product using the Nextera DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) according to manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq sequencers to generate 150 bp paired-end reads.

Bioinformatic analysis of target loci

Illumina MiSeq reads (150bp paired-end) were trimmed to 120bp after reviewing base quality profiles, in order to drop lower quality 3’ ends. Traces of Nextera adapters were clipped using the FASTX toolkit (Hannon Lab, CSHL) and pairs with each read greater than 15bp in length were retained. Additionally, read pairs where either read had 50% or more bases below a base quality threshold of Q30 (Sanger) were dropped from subsequent analyses. The reference sequence of the target locus was supplemented with 10 bp genomic flanks and was indexed using an enhanced suffix array55. Read ends were anchored in the reference sequence using 10 bp terminal segments for a suffix array index lookup to search for exact matches. A sliding window of unit step size and a maximal soft-clip limit of 10 bp was used to search for possible anchors at either end of each read. For each read, optimal Smith-Waterman dynamic programming alignment56 was performed between the reduced state space of the read sequence and the corresponding reference sequence spanning the maximally distanced anchor locations. Scoring parameters were selected to allow for sensitive detection of short and long insertions and deletions while allowing for up to four mismatches, and the highest scoring alignment was selected. Read pairs with both reads aligned in the proper orientation were processed to summarize the number of wild-type reads and the location and size of each insertion and deletion event. Overlapping reads within pairs were both required to support the event if they overlapped across the event location. Additionally, mutation events and wild-type reads were summarized within the extents of the sgRNA sequence and PAM site by considering read alignments that had a minimum of 20 bp overlap with this region. Mutation calls were translated to genomic coordinates and subsequently annotated using Annovar57. The alignment and post-processing code was implemented in C++ along with library functions from SeqAn58 and SSW59 and utility functions in Perl and R (www.R-project.org). Mutation calls were subjected to manual review using the Integrated Genomics Viewer (IGV)60.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analysis was carried out as indicated in the Figure Legends, Extended Data Figure Legends and in the Methods for each experiment. The data were found to meet the assumptions of the statistical tests. Variation was estimated for each group of data the variance was found to be similar between groups that were compared. No animals were excluded from any of the studies. The investigator was blinded with respect to group assignment for the quantification of 3D spheroids, proliferating (Ki67+) cells and for the analysis of healthy lung volume by μCT. Power calculations were performed to estimate the sample size for experiments involving LGK974 treatment. Briefly, to detect a difference of 30% in average survival between the two groups (effect size = 1.2 standard deviation of survival based on Cohen’s d61 using untreated sample baseline survival from Jackson et al.39) with 90% power a minimum of 5 mice/group needed to be used.

Data availability statement

Massively parallel sequencing data are available in the NCBI/SRA data repository under accession PRJNA379539. Source code and all other data are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Inhibiting Wnt synthesis with the Porcupine inhibitor LGK974 suppresses Wnt pathway activation by the R-spondin/Lgr5 axis in primary lung adenocarcinoma cultures.

a, Percent of EdU+ (proliferating) cells in 3-dimensional (3D) cultures of KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) cells followed by Wnt pathway stimulation with Rspo1 (1 μg/ml), Wnt3a (100 ng/ml), or RW (1 μg/ml Rspo1 + 100 ng/ml Wnt3a), or Wnt pathway inhibition with LGK974 (100 nM) or DKK1 (500 ng/ml) for 7 days (starting at 7 days after plating). EdU labeling was performed 16h before analysis of proliferating cells by flow cytometry. N = 6 wells/condition. b, Percent of spheroids proliferating in low-density 3D cultures of primary mouse KPT LUAD cells 14 days after plating. N = 8 wells/condition. Representative data from 8 replicate experiments; TT5678 and TT5861 identify donor mice. c, Quantitative PCR of Porcn transcripts in sublines of a KP LUAD cell line expressing shRNAs targeting Porcn (shPorcn) or control shRNA (shLuc). Quantification of 3D tumour spheroids containing EdU+ cells of KP LUAD cells expressing the indicated shRNAs in response to 100 ng/ml Wnt3a or control at 6 days after plating. Representative data of n = 3 technical replicates, the experiment was performed with three independent cell lines. e, Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of Axin2 and Lgr5 transcripts in 3D cultures of primary KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ (KP) LUAD cells following Wnt pathway stimulation with Rspo1 (1 μg/ml), Wnt3a (100 ng/ml), or RW (1 μg/ml Rspo1 + 100 ng/ml Wnt3a), or Wnt pathway inhibition with LGK974 (100 nM) or DKK1 (1 μg/ml) for 6 days (starting at 10 days after plating). Representative data of n = 3 technical replicates, the experiment was carried out three times, each time with cells isolated from different tumor-bearing mouse. f, Quantification of tumour spheroids containing EdU+ cells per 100 primary KPT LUAD cells 14 days after plating. RW (1 μg/ml Rspo1 + 100 ng/ml Wnt3a); LGK974 (100 nM). N = 8 wells/condition. g, Recipient mouse lungs 8 weeks following orthotopic transplantation of 30,000 primary tdTomato+ (red) primary mouse KP LUAD cells. Arrowheads indicate tdTomato+ tumours. Recipient mice were treated with 10 mg/kg/d LGK974 or vehicle for 8 weeks, starting from the day of transplantation. Scale bar: 2 mm. The experiments was performed three times, each time with cells isolated from different (donor) tumor-bearing mouse. h, Wnt pathway activity measured by detection of firefly luciferase driven by a Wnt-sensitive 7TCF promoter (TOPFLASH assay) in murine KP LUAD cells stimulated for 24h with the indicated growth factors. N = 3 technical replicates/condition. Representative data from experiments that were performed with four different cell lines. i, j, k, Quantitative PCR analysis of Rspo2 (i), Rspo3 (j) or Lgr5 (k) transcripts in two independent murine KP LUAD cell lines (TT5734 and TT5764) expressing Synergistic Activation Mediator (SAM) components21 driving expression of the indicated genes. l, Flow cytometry analysis of GFP fluorescence in a KP LUAD cell line harboring the Lgr5GFP-CreER reporter36 expressing vector control (top panel) or an sgRNA targeting the transcription start site of Lgr5 (bottom panel). m, n, qRT-PCR analysis of the Wnt target genes Axin2 (m) and Lgr5 (n) in 3D cultures of sublines of a KP LUAD cell line (TT5764) expressing the CRISPR-activator system driving expression of Rspo2 (Rspo2-a), Rspo3 (Rspo3-a) or Lgr5 (Lgr5-a). * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001. Two-way ANOVA: (a), (b), (d), (h), (m), (n); Student’s two-sided t-test: (c), (e), (f), (i), (j), (k); error bars: +SD.

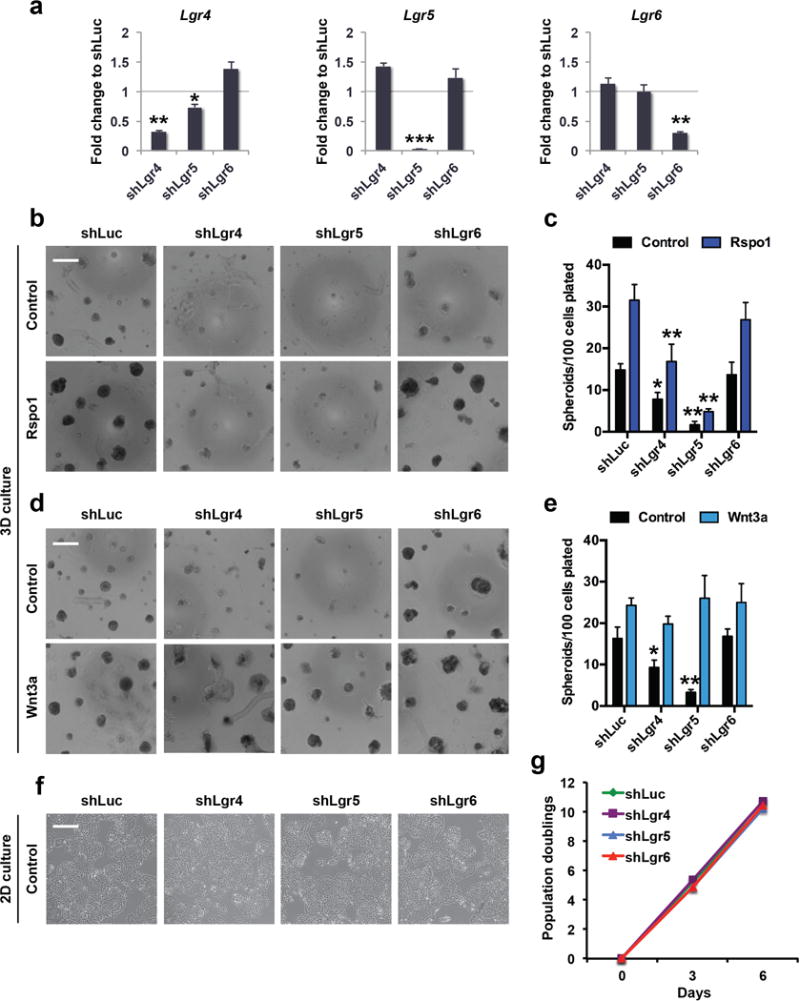

Extended Data Figure 2. Lgr4 and Lgr5 are R-spondin receptors in lung adenocarcinoma.

a, Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of Lgr4, Lgr5, and Lgr6 transcripts in sublines of a KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ (KP) LUAD cell line stably expressing shLgr4, shLgr5, shLgr6, or shLuciferase (shLuc) control. Note minimal effects of the indicated shRNAs on other Lgr5 family members. N = 3 technical replicates/condition; representative data from 3 experiments carried out in different cell lines. b, c, Formation of 3D tumour spheroids of sublines of a KP LUAD cell line expressing the indicated shRNAs in response to 1 μg/ml Rspo1 (b, c) or 100 ng/ml Wnt3a (d, e) 6 days after plating. Scale bars: 500 μm. N = 8 wells/condition, representative data from 3 experiments carried out in different cell lines. f, g, No difference in cell morphology (f) or growth rate (g) in sublines of a KP LUAD cell line expressing shLgr4, shLgr5, shLgr6, or control shLuciferase (shLuc) over 6 days in 2-dimensional cell culture. Scale bar: 200 μm. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001. Student’s two-sided t-test: (a); two-way ANOVA: (c), (e), (g); error bars: +SD. All experiments in this figure were performed three times, each time with a different KP LUAD cell line.

Extended Data Figure 3. Wnt ligands produced predominantly by cancer cells drive activation of the Wnt signaling pathway in lung adenocarcinoma.

a, Schematic representation of the lentivirus vector46 used to transduce a KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) LUAD cell line, followed by puromycin selection. b, tdTomato and 7TCF::Luciferase signals at baseline (0h) and 48h following treatment with 10 mg/kg/d LGK974 or vehicle. Red arrows indicate two subcutaneous tumours with reduced 7TCF-dependent bioluminescence in response to 48h of LGK974 treatment. c, Suppression of 7TCF-driven bioluminescence by LGK974 relative to tdTomato signal in mice harboring subcutaneous transplants of the KPT LUAD cell line stably expressing the 7TCF::Luciferase-PGK-Puro lentivirus. N = 6 tumours, 3 mice per group. Representative data from two independent experiments. Student’s two-sided t-test; error bars: ±SD. d, Haematoxylin-eosin (HE) or β-catenin staining in KP adenomas or in adenocarcinomas. Scale bars: 100 μm. e, Immunofluorescence for β-catenin (red) and Porcupine (green) in a KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ (KP) lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). Scale bar: 100 μm. f, In situ hybridization (ISH) for Axin2 mRNA (purple, arrowheads) in KP lung adenomas or adenocarcinomas. Scale bar: 50 μm. g, Immunofluorescence for Porcupine (green, white arrowheads) and ISH for Axin2 (red, yellow arrowheads) in KP LUAD. Scale bar: 10 μm. h, Immunofluorescence for Porcupine (green) in an autochthonous grade 3 KPT adenocarcinoma. Arrowheads indicate peritumoural Porcupine+ cells, which are tdTomato negative (i.e. not cancer cells). Scale bar: 100 μm. i, CD11b (green) and Porcupine (red) immunofluorescence in a peritumoural region. White line delineates tumour (T). Scale bar: 100 μm. j, Immunohistochemistry for β-catenin or Porcupine in human LUAD. Arrowheads indicate cells with nuclear β-catenin. Scale bar. 100 μm. 65 human LUAD tumors in two tissue microarrays were analysed. k, Comparison of PORCN gene expression in tumours versus normal tissue in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) lung adenocarcinoma cohort: Empirical cumulative density function (CDF) plots of standardized gene expression values are shown. A right-shift indicates relatively higher expression, with P-values indicated to assess statistical significance (KS-test).

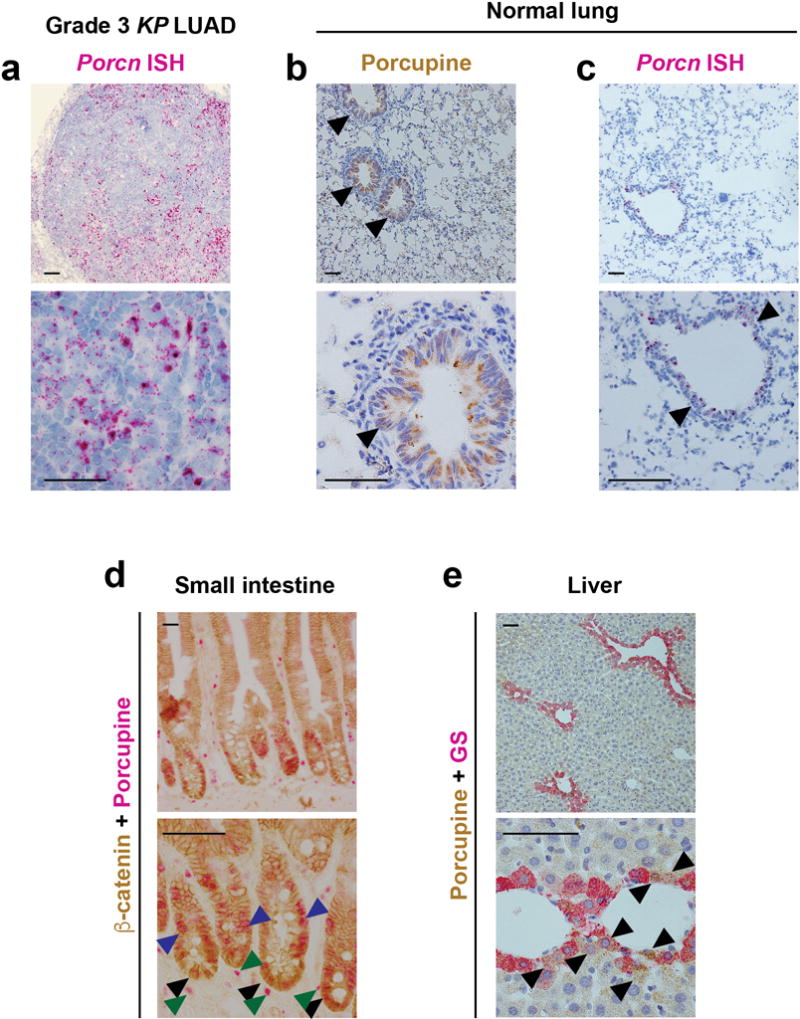

Extended Data Figure 4. Expression of Porcupine in lung adenocarcinoma, the normal lung and in stem cell niches of the intestine and liver.

a, In situ hybridization (ISH) for Porcn in a grade 3 KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ (KP) lung adenocarcinoma. b, c, Immunohistochemistry for Porcupine (brown) (b), or Porcn in situ hybridization (ISH) in the normal lung (c). Arrowheads indicate Porcupine expression in bronchioles. d, Immunohistochemistry for β-catenin (brown) and Porcupine (purple) in the small intestine. Note Porcupine expression in intestinal crypts (black arrowheads), the location of Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells36, as well as in transit-amplifying cells (blue arrowheads) and stromal cells (dark green). e, Immunostaining for Porcupine (brown) and glutamine synthetase (GS, purple) expression localizes to areas around the central vein of the liver (e), coinciding with the location of Lgr5+/Axin2+ liver stem cells8,62. Scale bars: 100 μm.

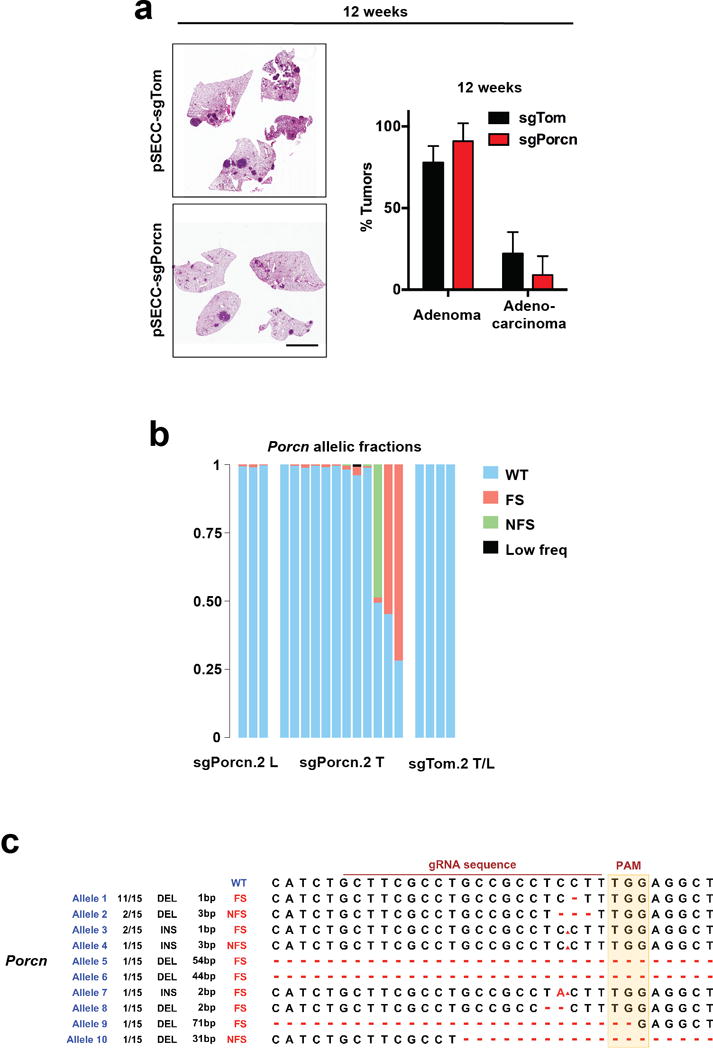

Extended Data Figure 5. Analysis of the Porcn locus following CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in vivo.

a, Haematoxylin-eosin staining of KP LUAD-bearing lungs generated with pSECC-sgTom or pSECC-sgPorcn and quantification of the proportion of adenomas vs. adenocarcinomas at 12 weeks following tumour initiation. Scale bar: 2 mm. Student’s two-sided t-test; error bars: +SD. N = 5 mice per group. b, Massively parallel sequencing analysis of allelic fractions of the Porcn locus in lung lobes containing microscopic tumours (“sgPorcn.2 L”) or microdissected macroscopic tumours (“sgPorcn.2 T”) induced in KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53flox/flox (KP) mice using pSECC-sgPorcn.2, or in lung lobes or macroscopic tumours induced in KP mice using pSECC-sgTom.2 (“sgTom.2 T/L”). WT: wild-type read; FS: frameshift mutation; NFS: non-frameshift mutation; Low freq: low-frequency mutation event. Note predominantly wild-type or non-frameshifting reads in microdissected tumours, whereas mutations in tumours containing microscopic tumours have introduced frameshifts. The large contribution of wild-type reads in “sgPorcn.2 L” samples is due to domination of the normal stroma in whole-lobe samples, whereas wild-type reads in sgPorcn.2 T indicate cancer cells where genome editing did not function, as in whole tumour samples tumour cells are expected to contribute at least 50% (ref. 49). c, Qualitative analysis of mutations introduced by sgPorcn.2 in vivo. INS: insertion; DEL: deletion; bp: base pair (indicates size of insertion/deletion). Ratio indicates frequency of event across 15 samples analysed.

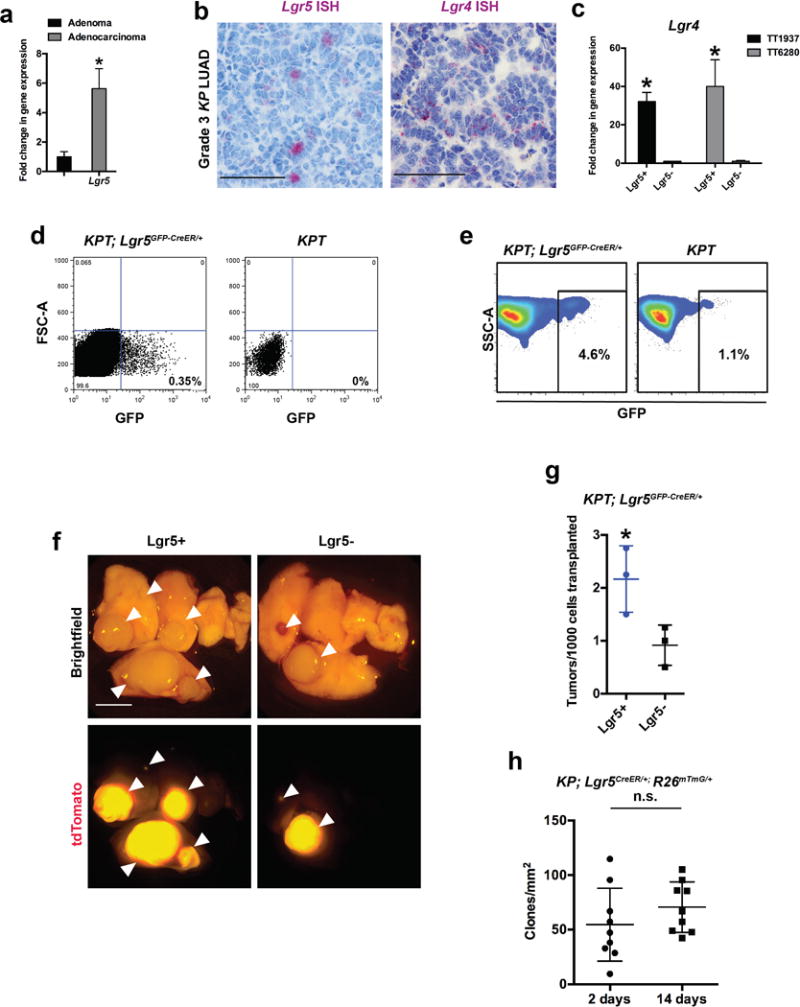

Extended Data Figure 6. Lgr5 and Lgr4 are expressed in lung adenocarcinoma, and Lgr5 marks cells with increased tumour-forming ability.

a, Quantitative PCR analysis of Lgr5 gene expression in KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ (KP) LUAD tumours microdissected at 9 weeks (adenomas) or 20 weeks (adenocarcinomas) post-initiation with adenoviral Cre. N = 6 tumors/group. b, In situ hybridization (ISH) for Lgr5 or Lgr4 mRNA (purple) in grade 3 KP LUAD adenocarcinomas 12 weeks following tumour induction with AdCre. Scale bars: 100 μm. c, d, FACS sorting (d) of Lgr5+ (GFP+) cells in cultured KP LUAD cell line containing the Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ reporter allele (KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+), followed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis (c) of Lgr4 expression in Lgr5+ cells in two independent cell lines (TT1937 and TT6280). This experiment was performed once. e, Fluorescence-assisted cell sorting (FACS) of GFP+ and GFP- cells isolated from KPT; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ primary LUAD 14 weeks following tumour initiation with intratracheally administered AdCre. The FACS plot is gated on tdTomato+/CD11b−/CD31−/CD45−/TER119− cells. Note bleeding of the tdTomato signal to the GFP channel in the panel on the right. Gates were drawn as shown to increase cell yield at the cost of purity to enrich for Lgr5+ cells. Such FACS sorting was performed on 21 KPT; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+ mice. f, Recipient mouse lungs 12 weeks following orthotopic transplantation of 15,000 primary Lgr5+/tdTomato+ or Lgr5−/tdTomato+ primary mouse LUAD cells. Arrowheads indicate tdTomato+ tumours (red). Scale bar: 2 mm. Representative data from three replicate experiments. g, Quantification of tumours per 1000 cells in recipient mouse lungs 12 weeks following orthotopic transplantation of 15,000 primary Lgr5+/tdTomato+ or Lgr5−/tdTomato+ primary mouse LUAD cells. N = 3 recipient mice per group; representative data from three replicate experiments. *P < 0.05. h, Number of membrane-associated GFP+ (mG+) clones following lineage-tracing in established subcutaneous KP; Lgr5CreER/+; Rosa26LSL-mTmG/+ LUAD primary transplants (see Figure 3c). N = 9 tumors/time point. Student’s two-sided t-test: (a), (c), (g), (h). *P < 0.05, n.s. = not significant: error bars: +SD.

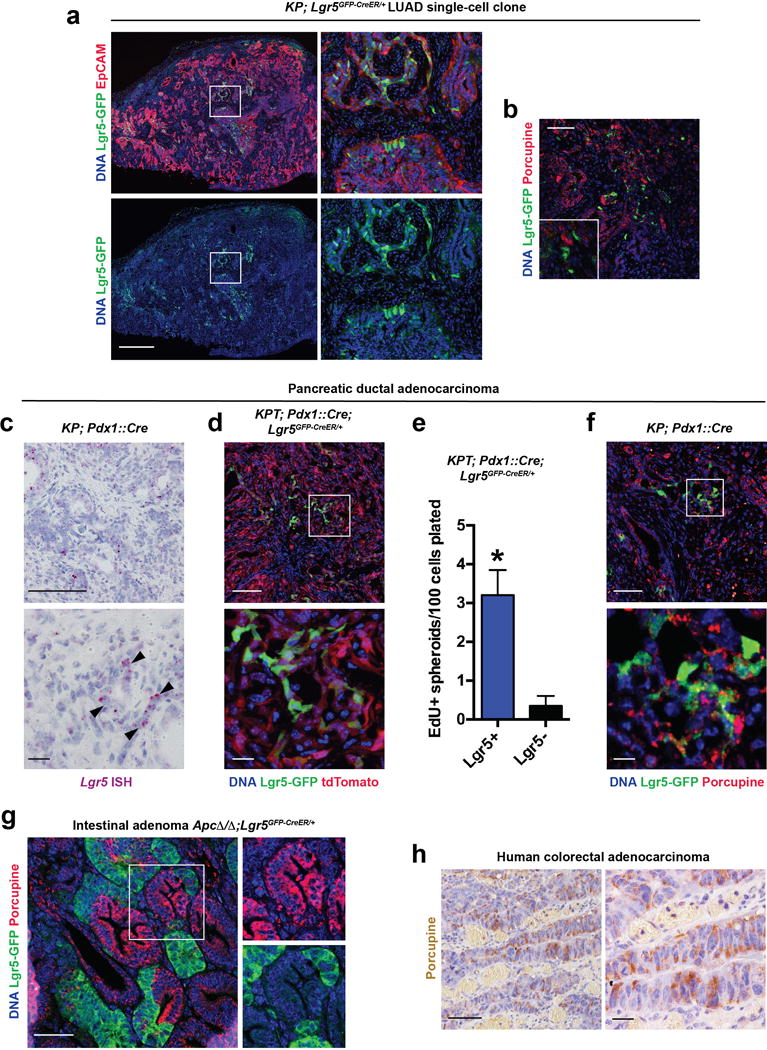

Extended Data Figure 7. Phenotypical plasticity of Lgr5+ cells that reside in Porcupine+ niches in lung, pancreatic and colon tumours.

a, Immunofluorescence for GFP (green) and EpCAM (red) in a subcutaneous transplant established from a single-cell clone of KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Lgr5CreER/+ cell line. Scale bar: 1 mm. b, Immunofluorescence for GFP (green) and Porcupine (red) in a subcutaneous transplant established from a single-cell clone of KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Lgr5CreER/+ cell line. (a, b) are representative data from four replicate experiments, each with a different KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Lgr5CreER/+ cell line. c, ISH for Lgr5 mRNA (purple) in KP; Pdx1::Cre pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Scale bars: 100 μm (top) and 10 μm (bottom). Representative data from 3 PDAC tumors analysed. d, Immunofluorescence staining for GFP (green) in a tdTomato+ (red) autochthonous KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+; Rosa26tdTomato/+; Pdx1::Cre PDAC. Scale bars: 100 μm (top) and 10 μm (bottom). e, Quantification of primary spheroids containing EdU+ cells per 100 Lgr5+/tdTomato+ or Lgr5−/tdTomato+ primary mouse PDAC cells plated. N = 4 wells/group. *P < 0.05, Student’s two-sided t-test; error bars: +SD. f, Immunofluorescence staining for GFP (green) and Porcupine (red) in autochthonous KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+; Pdx1::Cre PDAC. Note juxtaposition of Lgr5+ and Porcupine+ cells in the tumours. Scale bars: 100 μm (top) and 10 μm (bottom). (d, f) Representative data from 6 KP; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+; Pdx1::Cre PDAC tumors analysed. g, Immunofluorescence staining for GFP (green) and Porcupine in an autochthonous ApcΔ/Δ; Lgr5GFP-CreER/+intestinal adenoma. Again, note juxtaposition of Lgr5+ and Porcupine+ cells in the tumours. Scale bar: 100 μm. N = 3 tumor samples. h, Immunohistochemistry for Porcupine (brown) in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Scale bars: 100 μm (top) and 10 μm (bottom). 5 human colorectal adenocarcinoma samples were analysed.

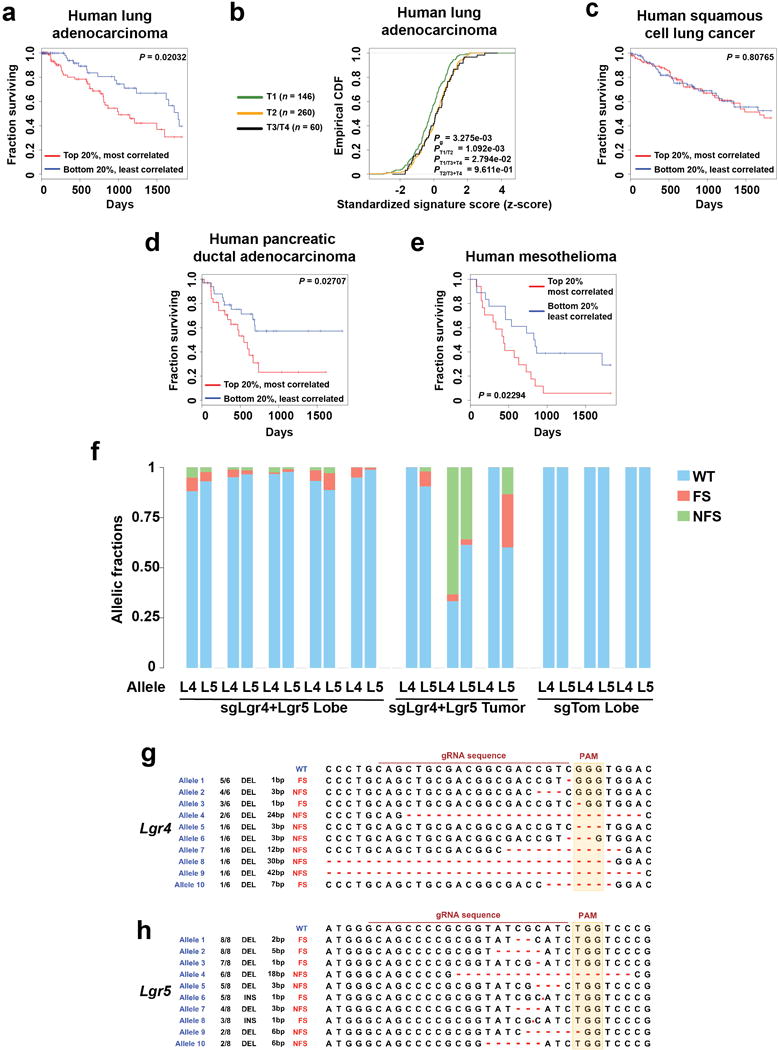

Extended Data Figure 8. Wnt pathway activation correlates with poor survival in human lung adenocarcinoma, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and mesothelioma, but not in human squamous cell lung cancer; analysis of the Lgr4 and Lgr5 loci following CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing in vivo.

a, Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing the 20% strongest (red, n = 91) and weakest (blue, n = 92) Willert Wnt signature correlated patients from the TCGA Lung Adenocarcinoma cohort. b, Empirical cumulative density function (CDF) plots of standardized gene expression values showing a correlation between the Wnt pathway activation gene expression signature correlation score and histological grade of primary tumours. A right-shift indicates relatively higher expression, with P-values indicated to assess statistical significance (KS-test). c-e, Kaplan-Meier survival curvex comparing the 20% strongest (red) and weakest (blue) Willert Wnt signature correlated patients from the TCGA Squamous Cell Lung Cancer (most-correlated/red n = 100, least-correlated/blue n = 100) (c), Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (most-correlated/red n=34, least-correlated/blue n=34) (d), and Mesothelioma (most-correlated/red n=17, least-correlated/blue n=18) (e) cohorts. f, Massively parallel sequencing analysis of allelic fractions of the Lgr4 and Lgr5 loci in lung lobes containing microscopic tumours (“Lobe”) or microdissected macroscopic tumours (“Tumour”) induced in KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53flox/flox; Rosa26LSL-Cas9+2a+eGFP/+ mice using hU6::sgLgr4-sU6::sgLgr5-EFS::Cre (pU2SEC) or hU6::sgTom-EFS::Cre (pUSEC) lentiviral vectors. WT: wild-type read; FS: frameshift mutation; NFS: non-frameshift mutation. Note predominantly wild-type or non-frameshifting reads in microdissected tumours, whereas mutations in tumours containing microscopic tumours have introduced frameshifts. The large contribution of wild-type reads in “Lobe” samples is due to domination of the normal stroma in whole-lobe samples, whereas wild-type reads in Lgr4/Lgr5 co-targeted tumours indicate cancer cells where genome editing did not function, as in whole tumour samples tumour cells are expected to contribute at least 50% (ref. 49). g, h, Qualitative analysis of mutations introduced by sgLgr4 or sgLgr5 in vivo. INS: insertion; DEL: deletion; bp: base pair (indicates size of insertion/deletion). Ratio indicates frequency of event across all samples analysed. P-values are indicated in the figure (log-rank test).

Extended Data Figure 9. Characterization of the niche for stem-like cells in lung adenocarcinoma.

a, Quantitative PCR analysis of Rspo gene expression in 16 KP LUAD tumours, normalized to Actb expression. Tumours were harvested at 16 weeks post-initiation with adenoviral Cre. In situ hybridization (ISH) for Rspo1 mRNA (purple, arrowheads) in a KP LUAD tumour. Note Rspo1 transcripts in endothelial cells. b, qPCR for Rspo1 and Rspo3 in tdTomato+ tumour cells (Tumour), CD31+ endothelial cells and the rest of the cells (Stroma) in microdissected KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) LUAD tumours following sorting. The expression of Pecam1 (that encodes CD31) was found to be >400-fold enriched in the CD31+ fraction compared to the stroma (not shown). N = 3 mice, representative from two replicate experiments. c, Heatmap showing relative expression levels of Porcn and the 19 murine Wnt genes based on quantitative PCR analysis in sorted tdTomato+ KP LUAD cells (T) vs. tdTomato- stromal cells (S) in microdissected tumours harvested at 20 weeks post tumour initiation (a time point when most tumours are adenocarcinomas). d, Volcano plot of qPCR array gene expression analysis showing statistically significant differentially expressed genes (in red, Fzd receptors are circled). X-axis is the log2 fold-change (Tumour/Stroma) and Y-axis is the –log10 P-value of the differential enrichment (2-sided t-test). e, Quantitative PCR analysis of Wnt5a, Wnt7a and Wnt7b gene expression in KP tumours microdissected at 9 weeks (adenomas) or 20 weeks (adenocarcinomas) post-initiation with adenoviral Cre. N = 6 mice, representative from two replicate experiments. f, Comparison of WNT gene expression in tumours versus normal tissue in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) lung adenocarcinoma cohort: Empirical cumulative density function (CDF) plots of standardized gene expression values for WNT5A, and WNT7B are shown. A right-shift indicates relatively higher expression, with P-values indicated to assess statistical significance (KS-test). g, Heatmap showing relative expression levels of Lrp5, Lrp6 and 9 murine Fzd genes based on quantitative PCR analysis in sorted tdTomato+ KP LUAD cells (T) vs. tdTomato- stromal cells (S) in microdissected tumours harvested at 20 weeks post tumour initiation (a time point when most tumours are adenocarcinomas). h, Quantitative PCR analysis of 8 Fzd receptors in KP tumours microdissected at 9 weeks (adenomas) or 20 weeks (adenocarcinomas) post-initiation with adenoviral Cre. N = 3 mice. Student’s two-sided t-test: (b), (e), (h); *P < 0.05; error bars: +SD.

Extended Data Figure 10. Porcupine inhibition suppresses Wnt pathway activity, progression and proliferative potential in autochthonous murine KP lung adenocarcinomas.

a, Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of Axin2 and Lgr5 transcripts in KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ (KP) LUAD tumours 2 weeks following treatment with 10 mg/kg/d LGK974 or vehicle. Treatment was started at 11 weeks post-tumour initiation. N = 6 tumors/group. b, Quantification of μCT data showing change in tumour volume compared to baseline (obtained at 76 days post tumor initiation, dashed line) after 4 weeks of 10 mg/kg/d LGK974 or vehicle control. c, Recipient mouse lungs 4 weeks following orthotopic GEMM-DA of 50,000 primary tdTomato+ (red) primary mouse LUAD cells. Arrowheads indicate tdTomato+ tumours. Donor mice bearing autochthonous KrasG12D/+; Trp53Δ/Δ; Rosa26tdTomato/+ (KPT) LUAD tumours were treated for 2 weeks with LGK974 or vehicle (black box, starting at 84 days post-tumour induction). The recipient mice were treated with LGK974 or vehicle (white box) for 4 weeks. Scale bar: 2 mm. d, tdTomato+ tumours in sections from lungs in (c) containing EdU+ cells (white arrowheads) or not containing EdU+ cells (yellow arrowheads). Scale bars: 500 μm (top) and 100 μm (bottom). e, Quantification of EdU+ (black) or EdU- (gray) tumours per section through the lungs depicted in (c, d). N = 5 (Vehicle-Vehicle), epresentative data from three replicate experiments. *P < 0.05; Student’s two-sided t-test: (a, b); two-way ANOVA (e); error bars: ±SD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. McFadden and P. Sharp for critical reading of the manuscript and T. Papagiannakopoulos for helpful discussions; H. Clevers for Lgr5CreER/+ mice; Janssen Pharmaceuticals for human tissue; J. Roper for mouse colon adenoma tissue; R. T. Bronson for expertise in animal pathology; Y. Soto-Feliciano and S. Levine for massively parallel sequencing expertise; L. Gilbert, M. Horlbeck and J. Weissman for Lgr5 CRISPRa sgRNA sequences; A. Li for help with generation of TCGA data catalogues; M. Griffin, M. Jennings and G. Paradis for FACS support; E. Vasile for microscopy support; K. Cormier and the Hope Babette Tang (1983) Histology Facility for histology support; S. Bajpay, D. Canner, D. Garcia-Gali, R. Kohn, N. Marjanovich, K. Mercer, J. Replogle, and R. Romero for help with experiments; K. Anderson, I. Baptista, A. Deconinck, J. Teixeira, and K. Yee for administrative support; and the Swanson Biotechnology Center for excellent core facilities. This work was financially supported by the Transcend Program and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, the Lung Cancer Research Foundation, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and, in part, by the Cancer Center Support (core) grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute. T.T. is supported by the National Cancer Institute (K99 CA187317), the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Hope Funds for Cancer Research, and the Maud Kuistila Foundation. T.J. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, a David H. Koch Professor of Biology, and a Daniel K. Ludwig Scholar.

Footnotes

Author contributions

T.T. and T.J. designed and directed the study; T.T., K.W., Y.P. and R.A.W. performed all types of experiments reported in the study; F.J.S.R. performed CRISPR-a experiments and analysed CRISPR-mutated loci; N.M.C. and K.H. performed gene expression analysis, and N.M.C. performed ISH; N.S.J., L.S. and P.K. performed FACS; R.A. and N.R.K. performed molecular cloning, and R.A. quantified Ki67+ nuclei; X.G. performed cell culture experiments; M.C.B. developed and used μCT analysis methodology; W.X. generated shRNA reagents; A.B. conducted bioinformatic analyses; F.J.S.R., N.S.J., Ö.H.Y., P.K., and A.B. provided conceptual advice; T.T. and T.J. wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors.

Author Information

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481:306–313. doi: 10.1038/nature10762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346:1248012. doi: 10.1126/science.1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogan BL, et al. Repair and regeneration of the respiratory system: complexity, plasticity, and mechanisms of lung stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herriges M, Morrisey EE. Lung development: orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development. 2014;141:502–513. doi: 10.1242/dev.098186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Lau W, Peng WC, Gros P, Clevers H. The R-spondin/Lgr5/Rnf43 module: regulator of Wnt signal strength. Genes Dev. 2014;28:305–316. doi: 10.1101/gad.235473.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schepers AG, et al. Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science. 2012;337:730–735. doi: 10.1126/science.1224676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huch M, et al. Unlimited in vitro expansion of adult bi-potent pancreas progenitors through the Lgr5/R-spondin axis. The EMBO journal. 2013 doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boumahdi S, et al. SOX2 controls tumour initiation and cancer stem-cell functions in squamous-cell carcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:246–250. doi: 10.1038/nature13305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Driessens G, Beck B, Caauwe A, Simons BD, Blanpain C. Defining the mode of tumour growth by clonal analysis. Nature. 2012;488:527–530. doi: 10.1038/nature11344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. 2013;501:328–337. doi: 10.1038/nature12624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilmer M, et al. RSPO2 Enhances Canonical Wnt Signaling to Confer Stemness-Associated Traits to Susceptible Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1883–1896. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng Y, et al. A rare population of CD24(+)ITGB4(+)Notch(hi) cells drives tumor propagation in NSCLC and requires Notch3 for self-renewal. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:59–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plaks V, Kong N, Werb Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:225–238. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson DH, Schiller JH, Bunn PA., Jr Recent clinical advances in lung cancer management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:973–982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juan J, Muraguchi T, Iezza G, Sears RC, McMahon M. Diminished WNT -> beta-catenin -> c-MYC signaling is a barrier for malignant progression of BRAFV600E-induced lung tumors. Genes Dev. 2014;28:561–575. doi: 10.1101/gad.233627.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacheco-Pinedo EC, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling accelerates mouse lung tumorigenesis by imposing an embryonic distal progenitor phenotype on lung epithelium. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI44871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart DJ. Wnt signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2014;106:djt356. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen DX, et al. WNT/TCF signaling through LEF1 and HOXB9 mediates lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cell. 138:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.030. doi:S0092-8674(09)00455-3[pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu J, et al. Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:20224–20229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konermann S, et al. Genome-scale transcriptional activation by an engineered CRISPR-Cas9 complex. Nature. 2014;517:583–588. doi: 10.1038/nature14136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willert J, Epping M, Pollack JR, Brown PO, Nusse R. A transcriptional response to Wnt protein in human embryonic carcinoma cells. BMC Dev Biol. 2002;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-213x-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocha AS, et al. The Angiocrine Factor Rspondin3 Is a Key Determinant of Liver Zonation. Cell Rep. 2015;13:1757–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]