Abstract

Self-healing polymers crosslinked by solely reversible bonds are intrinsically weaker than common covalently crosslinked networks. Introducing covalent crosslinks into a reversible network would improve mechanical strength. It is challenging, however, to apply this concept to‘dry’ elastomers, largely because reversible crosslinks such as hydrogen bonds are often polar motifs, whereas covalent crosslinks are non-polar motifs. These two types of bonds are intrinsically immiscible without co-solvents. Here we design and fabricate a hybrid polymer network by crosslinking randomly branched polymers carrying motifs that can form both reversible hydrogen bonds and permanent covalent crosslinks. The randomly branched polymer links such two types of bonds and forces them to mix on the molecular level without co-solvents. This allows us to create a hybrid ‘dry’ elastomer that is very tough with a fracture energy 13,500J/m2 comparable to that of natural rubber. Moreover, the elastomer can self-heal at room temperature with a recovered tensile strength 4MPa, which is 30% of its original value, yet comparable to the pristine strength of existing self-healing polymers. The concept of forcing covalent and reversible bonds to mix at molecular scale to create a homogenous network is quite general and should enable development of tough, self-healing polymers of practical usage.

Keywords: tough, self-healing, supramolecular, molecular design, elastomers

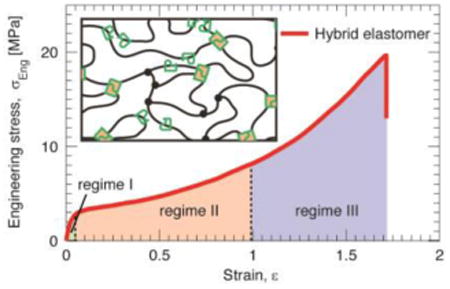

Graphical abstract

A tough, self-healing polymer network is fabricated by crosslinking randomly branched polymers carrying motifs that can form both reversible hydrogen bonds and permanent covalent crosslinks. The randomly branched polymer forces such two types of bonds to mix on the molecular level without co-solvents; this enables a hybrid ‘dry’ elastomer that with an exceptional combination of toughness and self-healing ability.

Self-healing polymeric materials can revert to their original state with full or partial recovery of mechanical strength after damage.[1, 2, 3] As such, they hold great promise to extend the lifetime of polymeric products in many fields; examples include aerospace, automotive, civil, and medical engineering.[4] Unlike classical polymer networks that are crosslinked by permanent covalent bonds, self-healing polymeric materials are often based on reversible associations, such as hydrogen bonds,[3, 5] metal-ligand coordination,[6, 7] host-guest interactions,[8] ionic interactions,[9] electrostatic interactions,[10, 11] hydrophobic associations,[12] π– π stacking,[13] or polymer entanglements[2, 14]. Such reversible associations can break and reform to enable self-healing ability, but they are nevertheless relatively weak compared to covalent bonds. Thus, the toughness of self-healing polymers does not match that of covalent polymer networks such as natural rubber.

Introducing permanent, covalent crosslinks into a reversible network would improve its mechanical properties, and this concept has been explored extensively to create tough hydrogels.[8, 11, 15, 16] However, hydrogels contain a large amount of water that can evaporate, whereas diverse applications often require polymers that are not only tough, but also dry, such that they do not leach molecules and change properties. Unfortunately, it is challenging to integrate both covalent and reversible networks in a ‘dry’polymer that does not contain co-solvents. Reversible crosslinks such as hydrogen bonds are often polar motifs, whereas covalent crosslinks are typically non-polar motifs. These two types of moieties are intrinsically immiscible, although they can be mixed in the presence of co-solvents and/or if joined together.[17] Joining non-polar and polar moieties promotes them to mix without viscoelastic phase separation, and this, in particular, has been seen in some polymers containing both covalent and hydrogen bonded groups.[18] These bonds are joined by the polymer backbone, which forces them to mix on the molecular level. In a ‘dry’ polymer network, however, viscoelastic phase separation often occurs as joining polar and non-polar moieties is not sufficient to suppress their unfavorable enthalpic interactions. Consequently, despite its significant practical importance, it remains a challenge for the development of elastomers with an exceptional combination of toughness and self-healing ability.

Here we report a tough, self-healing ‘dry’elastomer that contains both covalent and reversible networks. The hybrid elastomer is fabricated by crosslinking a randomly branched polymer carrying motifs that can form both reversible hydrogen bonds and permanent covalent crosslinks. The randomly branched polymer links these two types of bonds and forces them to mix on the molecular level without viscoelastic phase separation. This allows us to create a homogenous, optically transparent ‘dry’ elastomer without co-solvents. At small deformations, the hydrogen bonds break and reform to dissipate energy. At large deformations, the hybrid elastomer exhibits patterns that are reminiscent of crazes observed in typical plastics, but are of much larger length scales, ranging from 1 to 1000 μm. These patterns are so-called ‘macro-crazes’; they are unique to the hybrid elastomer and help maintain material integrity at large deformations. The ability to sacrifice hydrogen bonds at small deformations and maintain material integrity at large deformations enables a very tough elastomer with fracture energy 13,500J/m2 comparable to that of natural rubber. Moreover, the hybrid elastomer self-heals at room temperature with a recovered tensile strength of 4 MPa, which is comparable, if not better, to the existing self-healing elastomers.

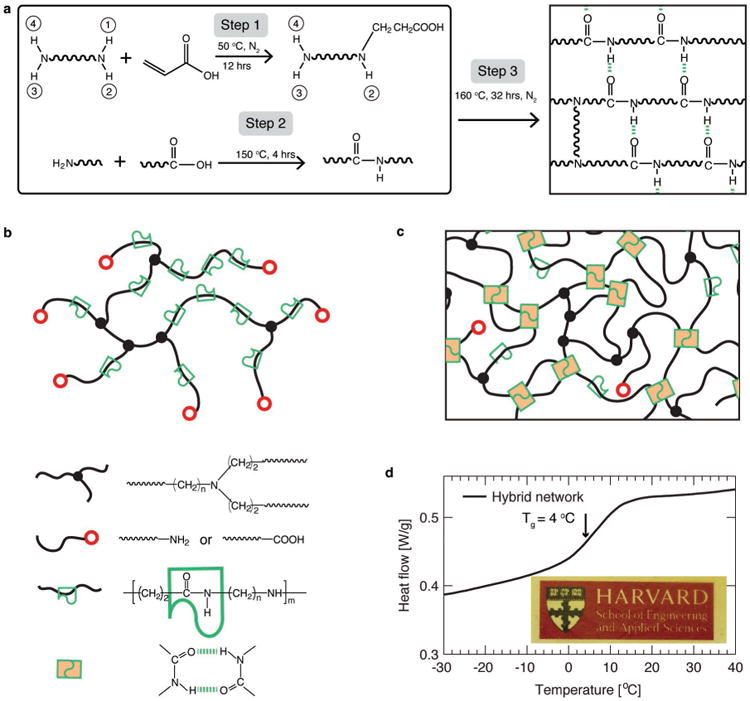

We first synthesize a randomly branched polymer carrying motifs that can form both reversible hydrogen and permanent covalent bonds. To this end, we use diamine molecules and acrylic acid as raw reagents, and keep the molar ratio between amine and carboxyl groups fixed at 1:1.25 (Materials and Methods). A diamine molecule has an amine group at each of its two ends. An amine group reacts with the unsaturated C=C in acrylic acid at 50°C through Michael addition, resulting in carboxyl functionalized molecules, as described by Step 1 in Figure 1a and detailed in Figure S1. A carboxyl group can further react with an amine group to form an amide group at relatively high temperature, 150°C, through condensation reaction, as described by Step 2 in Figure 1a. We allow the condensation reaction to proceed for about 4 hours to form randomly branched polymers. In a randomly branched polymer, the branching point is a tri-functional linker, the end groups are either carboxyl or primary amine groups, and along the backbone of branches are randomly distributed amide groups, as illustrated in Figure 1b. The chemical reactions and resulted functional groups are confirmed by Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements (SI Materials and Methods and Figures S2&S3).

Figure 1. Concept and synthesis of hybrid networks.

a, Synthesis of a hybrid network. Step 1: The double bond of an acrylic acid molecule reacts with one of the four N-H bonds in a diamine molecule through Michael addition, resulting in an oligomer with one end functionalized by a carboxyl group, whereas the rest three N-H bonds are still reactive to double bonds. There are four reactive hydrogen groups in a diamine molecule, and depending on the number of reacted hydrogen groups, five types of oligomers can be generated (Figure S1). Step 2: Polymerization of the oligomers formed in Step 1 through condensation reaction between the amine groups and carboxyl groups at 150°C; this forms a randomly branched polymer. Step 3: The randomly branched polymers are crosslinked to form a network through condensation between the amine groups and carboxyl groups. b, Illustration of a randomly branched polymer formed after Step 2. The polymer carries motifs that can form reversible bonds (green symbols) along the backbone of polymers and motifs that can form covalent bonds (red circles) at the end of branching arms. Filled black circles represent tri-functional covalent branching points. c, Illustration of the hybrid network formed after Step 3. The formation of covalent network is achieved by linking the end groups of the randomly branched polymer by condensation reaction, and the formation of reversible associations is illustrated by the change of a pair of empty green symbols to filled ones. The empty red circles represent carboxyl or amine groups, and the green empty symbols represent an amide group. d, Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis of a hybrid network. The glass transition temperature of the network is 4°C, indicating the material is an elastomer rather than plastic at room temperature. Inset: a representative image of a hybrid network.

The randomly branched polymers form a supramolecular network that is connected by either amide-amide or carboxyl-amine hydrogen bonds. Unlike permanent covalent bonds, these hydrogen bonds are temporary and can dissociate at room temperature; consequently, the network is a viscous liquid rather than a solid, as evidenced by the dynamic mechanical test in which the loss modulus is always higher than the storage modulus in a wide range of shear frequency (Figure S4). Moreover, the liquid becomes much less viscous at higher temperature, reflected by a dramatic decrease in loss modulus, as shown by the open symbols in Figure S4. This liquid-like feature is critical for the fabrication of a hybrid network. It promotes the mobility of reactive amine and carboxyl groups, and therefore, facilitates the condensation reaction between them, through which the precursor polymers are crosslinked to form a network. Moreover, the liquid-like feature allows the network to be molded to desired shapes.

After obtaining the viscous liquid, we transfer it into a Teflon mold, and maintain the temperature at 160°C for 32 hours. During this process, amine groups and carboxyl groups at the ends of branching arms react with each other through condensation reaction. This crosslinks randomly branched polymers to form a network, as described by Step 3 in Figure 1a. The network contains both reversible hydrogen bonds and permanent crosslinks, as illustrated by Figure 1c; thus, we call it a hybrid network. The network is an optically transparent solid, as shown by an optical image in the inset of Figure 1d. Such optical transparency reflects homogeneity of the network at molecular length scale; otherwise the intrinsic immiscibility between polar hydrogen bonds and non-polar covalent crosslinks would result in visible phase separation and optical turbidity. The homogeneity of the network is further demonstrated by small angle X-Ray scattering, which does not exhibit characteristic peaks associated with micro-phase separation (Figure S5). Moreover, the polymer network has a glass transition temperature of 4-14 °C that is below room temperature; therefore, the material is a rubbery elastomer rather than a glassy plastic at room temperature (Figure 1d).

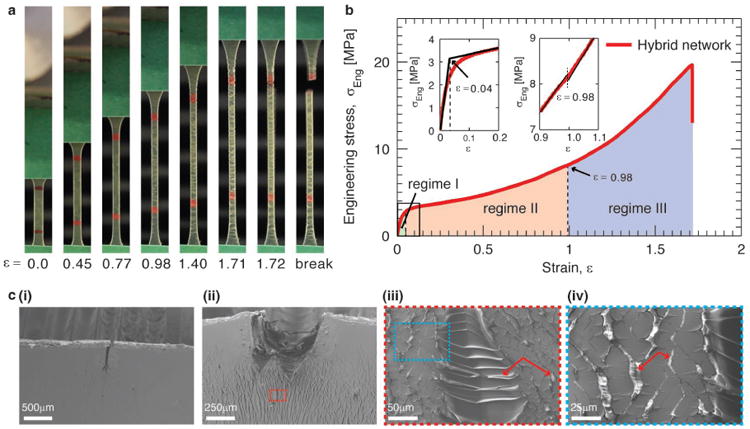

To characterize mechanical properties of the hybrid elastomer, we cut the material into dumbbell shape and quantify its stress-strain behavior using uniaxial tensile test (Materials and Methods). In a typical test, we stretch the sample at a controlled strain rate of 0.014/sec, and simultaneously monitor the elongation of the sample using a camera. Example images of the hybrid elastomer under different extents of strain are shown in Figure 2a, and a representative movie for a tensile test is shown in Movie S1. Examining the dependence of stress on strain reveals three distinct regimes for mechanical response. Regime 1:At small strain, ∊ < 0.04, the stress increases rapidly with strain in a linear manner (light green area and left inset in Figure 2b). Regime II: At intermediate strain, the rate of increase in stress slows down, yet maintains a nearly linear behavior (light red area in Figure 2b). Regime III: At large strain, ∊ > 0.98, the elastomer exhibits strain stiffening with the rate of increase in stress becomes higher compared to that in Regime II (light blue area in Figure 2b). Interestingly, the onset of Regime III is featured by an abrupt decrease in stress, as shown by the right inset in Figure 2b. Moreover, this decrease in stress is accompanied by the appearance of white lines that are perpendicular to the direction of elongation, as shown by the optical image of the sample at ∊ = 0.98 in Figure 2a. These white lines are reminiscent of crazing in plastics, which is due to localized large strain around defects[19], but are different in that they are distributed over the whole sample rather than being localized. Even more striking is the length scale on which they occur; the crazes are remarkably large and visible by eye, in contrast to conventional, micro-scale crazes in plastics. We therefore name these white lines ‘macro-crazes’.

Figure 2. Strain dependent mechanical properties.

a, Optical images of a hybrid elastomer at different strains, ε, when subjected to uniaxial tensile test. The hybrid elastomer is fabricated using a hexamethylenediamine/diaminododecane molar ratio 0.5/0.5 (Materials and Methods). b, Dependence of engineering stress, σeng, on the strain. The stress-strain curve can be divided into three regimes depending on the extent of strain: Regime I, ε <0.04; Regime II, 0.04<ε<1.0; Regime III, ε>1.0. The initiation of Regime III is associated with two features: (i) Mechanically the stress exhibits a sudden decrease (right inset), and (ii) visually the appearance of white imprints that are perpendicular to the direction of elongation at strain of 0.98 (Fig. 2a). c, Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the hybrid network with an initial notch under uniaxial tensile test in situ.

To explore the microstructure of these ‘macro-crazes’, we examine them in situ using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Materials and Methods). To do so, we introduce a notch on a rectangular sample, and monitor the formation of ‘macro-crazes’ near the notch as the sample is subjected to extension. Initially, the hybrid elastomer exhibits no ‘macro-crazes’ except the crack due to initial notch, as shown in Figure 2c(i). Upon stretching, ‘macro-crazes’are initiated and extended from the notch zone across the sample until rupture (Figure 2c(ii)). The ‘macro-crazes’ are small gaps with a wide distribution of widths ranging from ∼1μm to ∼1000μm, each connected by stretched lamellae aligned along the direction of elongation, as shown by the SEM images in Figure 2c(iii-iv). By contrast, conventional elastomers crosslinked solely by covalent bonds or supramolecular networks crosslinked solely by reversible bonds do not exhibit crazing upon deformation. Moreover, the hybrid elastomer maintains its integrity in the presence of a large amount of ‘macro-crazes’ at relatively large deformation, as shown by the images at ∊ > 0.98 in Figure 2a. The ability of the hybrid elastomer to withstand large deformation without breaking is likely due to the reversible bonds, which can break and reform, redistributing stress across the whole material and delaying accumulation of local stress.

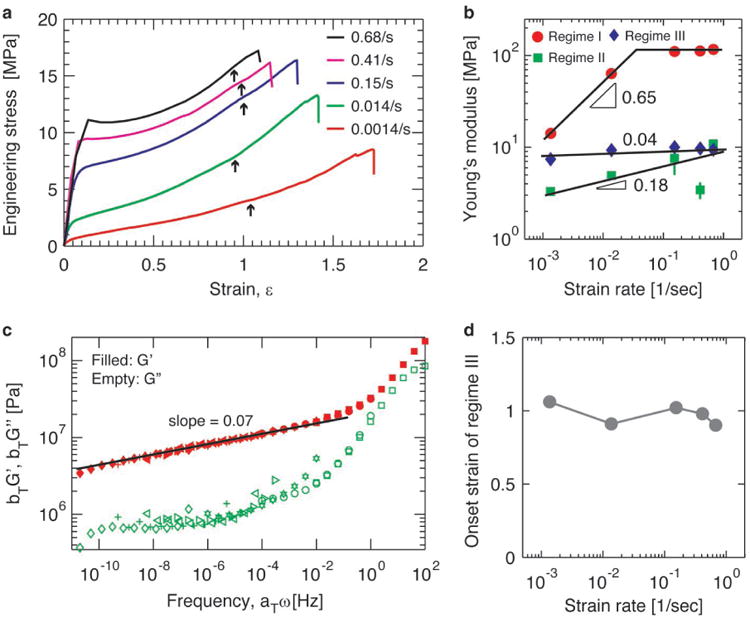

Unlike covalent bonds, reversible hydrogen bonds have a finite lifetime and can relax. Therefore, the mechanical properties of the hybrid elastomer depend on the rate of deformation. To explore this, we perform tensile tests at different strain rates for parallel hybrid elastomer samples. We vary the strain rate by nearly three orders of magnitude, from 0.0014/sec to 0.68/sec. For all strain rates explored, the stress-strain behavior is characterized by three regimes depending on the extent of deformation, as shown in Figure 3a. In each regime, the stress increases nearly linearly with strain, and the rate of increase describes the Young's modulus of the material. Interestingly, at small deformation in Regime I the Young's modulus is strain rate dependent. At small strain rates, ∊ < 0.01/sec, the Young's modulus in Regime I, EI, increases rapidly with strain rate, following a power law, EI ∝ ∊˙0.65, from approximately 10MPa to 100MPa; at larger strain rates, ∊˙ > 0.01/sec, EI saturates at approximately 100MPa, as shown by the circles in Figure 3b. The crossover strain rate is about 0.03/sec. Qualitatively such behavior can be understood based on the relaxation of reversible hydrogen bonds. A hydrogen bond has a finite average lifetime, and the lifetimes of all hydrogen bonds are randomly distributed around this mean.[20] Thus, a reversible bond can break at any time during the experiment, but is less likely at time scales shorter than the average lifetime. At shorter time scales, or at higher strain rates, the fraction of un-relaxed reversible bonds is larger than that at longer time scales. Consequently, the contribution to the network modulus due to reversible bonds increases with strain rate. At very high strain rates, however, this increase becomes saturated because nearly all hydrogen bonds are un-relaxed; therefore, the network moduli in the high strain rate limit become nearly a constant. Indeed, the crossover strain rate, 0.03/sec, is on the same order of magnitude as the reciprocal of the average lifetime of an amide-amide hydrogen bond[21].

Figure 3. Mechanical properties of hybrid elastomers at different strain rates.

a , Stress-strain curves at different strain rates for the hybrid elastomer with a hexamethylenediamine/diaminododecane molar ratio of 0.3/0.7. Arrows correspond to the strain at which the white lines appear. b, Young's modulus of hybrid elastomers at different strain rates in three regimes: small deformation (Regime I, circles), intermediate deformation (Regime II, squares), and large deformation (Regime III, diamonds). c, Frequency dependence of the storage (G′, filled symbols) and loss (G”, empty symbols) moduli of hybrid elastomer obtained by classical time-temperature superposition. The reference temperature is 20°C (squares), and measurements were performed at 40°C (circles), 60°C (hexagons) , 80°C (right triangles), 100°C (left triangles), 120°C (plus symbols), and 130°C (diamonds). The shift factors for the time-temperature superposition are listed in Materials and Methods. d, Dependence of onset strain for Regime III on strain rate.

Such understanding of strain rate dependent network modulus at small deformation is further supported by dynamic mechanical measurements (Materials and Methods). In a typical measurement, we quantify the network shear modulus at small strain, 0.05%, and oscillatory shear frequency from 0.01Hz to 100Hz. We perform such measurements at different temperatures, and construct a master curve using classical time-temperature superposition[22]; this allows us to probe the network shear modulus over an extremely wide range of frequencies. We find that the shear storage modulus, G′, increases weakly with effective frequency, ω, following a power-law, G′(ω) ∝ ω0.07. As ω increases from 10-11Hz to ∼1Hz, the storage modulus increases by nearly one order of magnitude from ∼3MPa to ∼30MPa, as shown by the red symbols in Figure 3c. Since the shear modulus is 1/3 of the Young's modulus for an elastomer with a Poisson ratio of 0.5, such increase in shear modulus is in quantitative agreement with that observed in uniaxial tensile tests, in which the Young's modulus at small deformation increases from 10MPa to 100MPa as the strain rate increases (the circles in Figure 3b). Moreover, at the lowest effective frequency, the magnitude of shear modulus, 3MPa, is consistent with equilibrium relaxation modulus, 2.5MPa, as shown by the stress relaxation curve in Figure S6. Together these measurements imply that the relaxation of reversible bonds determines the rate-dependent mechanical properties of the hybrid network at very small deformation.

At relatively large deformations, the mechanical properties of the hybrid network have a weak dependence on the strain rate: For intermediate deformations in Regime II, the Young's modulus increases with strain rate following a very weak power law, EII ∝ ∊˙0.18 (squares in Figure 3b); for large deformations in Regime III, the Young's modulus is essentially independent of strain rate, EIII ∝ ∊˙0.04 (diamonds in Figure 3b). The weak dependence in each regime is likely the result of most hydrogen bonds being broken under such large deformations. At a larger deformation, the network is subjected to a larger stress. A hydrogen bond under a higher tension is easier to break, as the tension lowers the energy barrier required for the bond to dissociate.[23] At very large deformations, such stress induced hydrogen bond dissociation likely saturates and nearly all hydrogen bonds are broken. Consequently, the major contribution to the network modulus is from permanent bonds, and this contribution nearly does not change with strain rate. Interestingly, the onset of Regime III, which is associated the initiation of ‘macro-crazes’, is nearly independent of strain rate, as shown in Figure 3d. Upon further deformation, these ‘macro-crazes’ continue to grow and help redistribute stress to maintain material integrity.

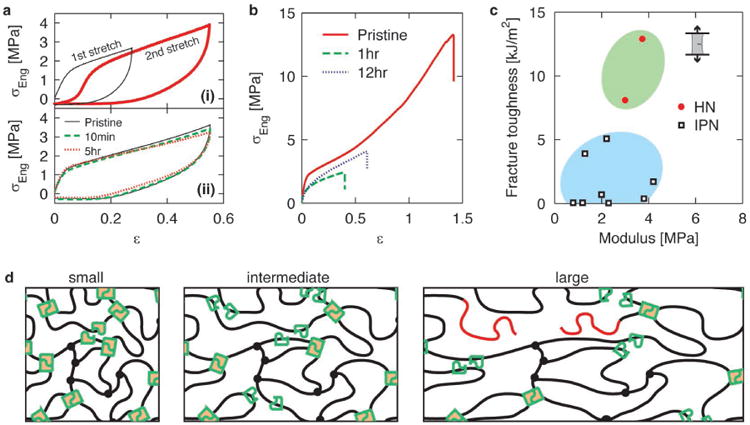

The ability to sacrifice hydrogen bonds at small deformation and maintain material integrity at large deformation allows the hybrid network to dissipate energy at multiple length scales. To quantify the efficiency of energy dissipation of these hybrid elastomers, we perform cyclic tensile tests at a fixed strain rate of 0.014/sec and at different deformations. In a typical test, there is a large hysteresis during the loading and un-loading processes, as shown by the stress-strain curve in Figure 4a(i). We define the efficiency of energy dissipation as the ratio between the integrated area in the hysteresis loop and that under the loading curve, and find that the efficiency is remarkably high, with a value of ∼75%; moreover, such high efficiency is nearly the same regardless of the extent of deformation, up to strains of 1.4, as shown in Figure S7. This suggests that the hybrid network is very dissipative, a characteristic feature of typical tough materials.[16] To quantify the fracture toughness of the hybrid network, we perform tensile tests on single-edge notched samples at a strain rate of 0.005/sec at room temperature, and calculate the fracture energy Gc using the Greensmith method (see SI Materials and Methods)[24]. For the hybrid network, Gc can reach values as high as13.5kJ/m2 (filled circles in Figure 4c), which is comparable to that of natural rubber under similar testing conditions.[25] Moreover, the toughness of the hybrid network is more than twice of recently reported tough interpenetrating dry networks (empty squares in Figure 4c)[26].

Figure 4. Self-healing properties and toughness of hybrid networks.

a, Hybrid network completely heals in Regime II under intermediate strain. (i) Thin, black line represents the first cyclic stretch, and the thick, red line represents the second cyclic stretch immediately after the first one. (ii), Solid line corresponds to the first stretch with strain up to that in Regime II; dashed line represents the second load after 10mins for the first load; dotted line corresponds to the cyclic test after waiting for 5 hours. b, Self-healing of hybrid networks in Regime III. Stress-strain curves for a pristine sample (red solid line), and parallel samples that are brought into contact for 1 hour (green dashed line) and for 12 hours (blue dotted line) after being cut into two parts. c, Comparison of toughness for hybrid networks (filled circles) and a recently developed tough interpenetrating networks (IPN) (open squares) [26]. d, Illustration of molecular structures for the hybrid elastomer under different extents of deformation.

Unlike interpenetrating elastomers formed by solely covalently crosslinked networks[26], these hybrid elastomers can self-heal because of reversible hydrogen bonds. For example, under intermediate deformations the hybrid elastomer recovers to its original mechanical properties after waiting for 10 mins or longer, as shown by stress-strain curves in Figure 4a(ii). Moreover, even after being cut into two pieces, the hybrid network can partially recover its mechanical strength. After bringing two freshly fractured surfaces into contact at room temperature, and waiting for 1 hour, the sample is able to support a stress of 2MPa. After 12 hours, the sample recovers a tensile strength of 4MPa, about 30% of its original value. Fracturing the sample breaks both the covalent and reversible bonds; only the reversible are reformed, resulting in the reduced value of the recovered tensile strength. Thus, the degree of healing of this hybrid elastomer is lower than that of self-healing ‘dry’ polymers which are formed solely with reversible bonds. Nevertheless, the absolute magnitude of the recovered tensile strength, 4MPa, of the hybrid elastomer is comparable to the pristine tensile strength of most self-healing elastomers.[3, 7, 27]

In summary, we have developed a hybrid elastomer by crosslinking randomly branched polymers carrying motifs that can form both reversible hydrogen bonds and permanent covalent crosslinks. The randomly branched polymer links such two types of bonds and forces them to mix on the molecular level, producing a homogenous, optically transparent elastomer. At small deformations, the reversible bonds break and reform to dissipate energy; at relatively large deformations, covalent bonds start to break, as illustrated in Figure 4d. However, the material maintains its integrity at large deformations because reversible bonds help redistribute stress; this feature is associated with ‘macro-crazing’ that is unique to this hybrid elastomer. Such synergy of energy dissipation at both molecular and macroscopic length scales produces an extremely tough elastomer that has fracture toughness comparable to natural rubber. However, the molecular mechanisms of ‘macro-crazing’ at large deformations, and how this behavior contributes to energy dissipation of the network, remain to be explained. Exploring these questions will require model networks of more controlled network structure and molar ratio between reversible and covalent crosslinks. In addition, the mechanical properties of the hybrid networks can be further optimized by tuning the strength of reversible bonds; for example, using relatively weak host-guest associations can significantly improve the network stretchability.[8] Nevertheless, the combination of optical transparency, toughness, and self-healing ability will enable applications of the hybrid elastomers in stretchable electronics and damping materials.[28] Moreover, the concept of using molecular design to mix covalent and reversible bonds to create a homogenous hybrid elastomer is quite general and should enable development of tough, self-healing polymers of practical usage.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

All chemicals were used as received unless otherwise noted. Acrylic acid (AA, 99%, ∼stabilized with 200ppm 4-methoxyphenol), 1, 12-diaminododecane (DADD, 99+%) and chloroform (99.8+%, stabilized with ethanol) were purchased from Alfa Aesar; 1, 6-hexamethylenediamine (HMDA, 98%) and N, N-dimethyl formamide (DMF, 99.8%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Synthesis

We synthesized the hybrid networks by two steps, pre-polymerization and crosslinking. During the pre-polymerization, 0.125 mole AA was added dropwise into 100 mL chloroform solution of DADD and HMDA under agitation at 50 °C in a three-neck round bottom flask. The molar ratio of -COOH in AA to -NH2 in diamine was fixed at 1.25:1, whereas that of HMDA/DADD was varied between 0.3/0.7 and 0.5/0.5. After the addition of AA, we stirred the solution at 50°C for 16 hours, and then heated it up to 80 °C and maintained the temperature for about 3 hours under nitrogen flow to remove chloroform. Subsequently, we raised the temperature to 150°C and maintained it for about 4 hours. The temperature was then lowered to 140°C, and 50 ml DMF was charged into the flask. This results in a solution that contains randomly branched polymers. In this process, DMF was used to lower the viscosity of randomly branched polymers, such that they can be further molded. The randomly branched polymers themselves are a homogenous, transparent liquid, and do not require co-solvents to mix. During the crosslinking step, we casted an aliquot of the solution in a Teflon mold, and placed this mold in a glass reactor with nitrogen inlet and outlet. We heated the glass reactor to 110 °C and maintained the temperature overnight to slowly evaporate DMF. The temperature was then increased to 160 °C with a rate of 10°C per hour, and was maintained at 160 °C for 32 hours, resulting in formation of a covalently crosslinked elastomer sheet with a thickness of ∼1mm.

Bulk rheology

Bulk rheological measurements were carried out on a strain controlled rheometer (ARES-G2, Texas Instruments) with 5mm plate-plate geometry. We cut a hybrid elastomer sheet into a circular shape with diameter of 5mm using a punch. The circular sample was glued to the plates to avoid slippage. Frequency sweeps were performed from 102 to 10-2 Hz at 0.5% stain at temperatures of 20°C, 40°C, 60°C, 80°C, 100°C, 120°C, and 130°C. Classic time-temperature superposition was constructed using 20°C as the reference temperature, and the shift factors are: aT = 1e-2 for 40°C, 1e-4 for 60°C, 3e-6 for 80°C, 6e-7 for 100°C, 5e-8 for 120°C, and 2e-9 for 130°C; bT = 293/T, in which T is the absolute temperature.

Mechanical test

We characterized the mechanical properties of hybrid elastomers using Instron® 3342 with a 1000N load cell. Uniaxial tensile measurements were conducted at room temperature in air under different strain rates, including 0.0014, 0.014, 0.14, 0.41 and 0.68/sec. We measured the strain by monitoring the displacement of two markers in the central part of a dumbbell shaped sample using a camera. Each measurement was repeated at least three times. Cyclic extension tests with incremental elongation were performed on the same tensile machine at a strain rate of 0.014/sec. The maximum strains of the cyclic tensile tests include 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1.1 and 1.4.

Scanning electron microscopy

We monitored the growth of ‘macro-crazes’ by performing tensile test in the chamber of an environmental scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Zeiss EVO 55). A notch of about 0.4 mm in length was made on a specimen of 4 mm width and 1mm thickness. The specimen was coated with a Pt/Pd layer of 5nm thickness and then fixed on a screw-driven tensile stage. The tensile stage was then placed inside the chamber of SEM, and images were taken around the tip of the notch. The stress and strain of the sample were continuously recorded at a strain rate of about 0.014/sec. Using SEM at an acceleration voltage of 5 kV, we monitored the formation of the ‘macro-crazes’ during the tensile process until the sample was broken.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.W. is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.: 51673120 and 51333003) and State Key Laboratory of Polymer Materials Engineering (Grant No. sklpme2017-3-05). This work is supported by NSF DMR-1310266, the Harvard MRSEC DMR-1420570, and NIH/NHLBI 5P01HL120839-03, and in part by Capsum under contract A28393. We thank Prof. Alfred Crosby, Prof. Zhigang Suo, Prof. Chinedum Osuji, and Prof. Cornelis Storm for enlightening discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- 1.Roy N, Bruchmann B, Lehn JM. Chemical Society reviews. 2015;44:3786. doi: 10.1039/c5cs00194c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang Y, Urban MW. Chemical Society reviews. 2013;42:7446. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60109a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zwaag S. Self healing materials: An alternative approach to 20 centuries of materials science. Springer Science; 2008. [Google Scholar]; Chen X, Dam MA, Ono K, Mal A, Shen H, Nutt SR, Sheran K, Wudl F. Science. 2002;295:1698. doi: 10.1126/science.1065879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; White SR, Sottos NR, Geubelle PH, Moore JS, Kessler M, Sriram SR, Kessler MR, Sriram SR, Brown EN, Iswanathan S. Nature. 2001;409:794. doi: 10.1038/35057232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu DY, Meure S, Solomon D. Prog Polym Sci. 2008;33:479. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordier P, Tournilhac F, Soulie-Ziakovic C, Leibler L. Nature. 2008;451:977. doi: 10.1038/nature06669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binder W. Self-Healing Polymers From Principles to Applications. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Kushner AM, Williams GA, Guan Z. Nat Chem. 2012;4:467. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Montarnal D, Tournilha Fo, Hidalgo M, Couturier eL, Leibler L. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7966. doi: 10.1021/ja903080c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnworth M, Tang L, Kumpfer JR, Duncan AJ, Beyer FL, Fiore GL, Rowan SJ, Weder C. Nature. 2011;472:334. doi: 10.1038/nature09963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rowan SJ, Beck JB. Faraday Discuss. 2005;128:43. doi: 10.1039/b403135k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kersey FR, Loveless DM, Craig SL. J R Soc Interface. 2007;4:373. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li CH, Wang C, Keplinger C, Zuo JL, Jin L, Sun Y, Zheng P, Cao Y, Lissel F, Linder C. Nat Chem. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nchem.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Tan CSY, Yu ZY, Li N, Abell C, Scherman OA. Advanced Materials. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201605325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Liu J, Tan CSY, Yu ZY, Lan Y, Abell C, Scherman OA. Advanced Materials. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201604951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalista SJ. Vol Master of Science. University Libraries Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University; Blacksburg, Va: 2003. [Google Scholar]; Das A, Sallat A, Böhme F, Suckow M, Basu D, Wieβner S, Stöckelhuber KW, Voit B, Heinrich G. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:20623. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b05041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bin Ihsan A, Sun TL, Kurokawa T, Karobi SN, Nakajima T, Nonoyama T, Roy CK, Luo F, Gong JP. Macromolecules. 2016;49:4245. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun TL, Kurokawa T, Kuroda S, Ihsan AB, Akasaki T, Sato K, Haque MA, Nakajima T, Gong JP. Nat Mater. 2013;12:932. doi: 10.1038/nmat3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang HJ, Sun TL, Zhang AK, Ikura Y, Nakajima T, Nonoyama T, Kurokawa T, Ito O, Ishitobi H, Gong JP. Adv Mater. 2016;28:4884. doi: 10.1002/adma.201600466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burattini S, Colquhoun HM, Fox JD, Friedmann D, Greenland BW, Harris PJ, Hayes W, Mackay ME, Rowan SJ. Chemical communications. 2009:6717. doi: 10.1039/b910648k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fox J, Wie JJ, Greenland BW, Burattini S, Hayes W, Colquhoun HM, Mackay ME, Rowan SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5362. doi: 10.1021/ja300050x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jud K, Kausch H, Williams J. J Mater Sci. 1981;16:204. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun JY, Zhao XH, Illeperuma WR, Chaudhuri O, Oh KH, Mooney DJ, Vlassak JJ, Suo ZG. Nature. 2012;489:133. doi: 10.1038/nature11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kean ZS, Hawk JL, Lin S, Zhao X, Sijbesma RP, Craig SL. Adv Mater. 2014;26:6013. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Li J, Suo Z, Vlassak JJ. J Mater Chem B. 2014;2:6708. doi: 10.1039/c4tb01194e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lin P, Ma S, Wang X, Zhou F. Adv Mater. 2015;27:2054. doi: 10.1002/adma.201405022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gong JP, Katsuyama Y, Kurokawa T, Osada Y. Adv Mater. 2003;15:1155. [Google Scholar]; Gong JP. Soft Matter. 2010;6:2583. [Google Scholar]; Webber RE, Creton C, Brown HR, Gong JP. Macromolecules. 2007;40:2919. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao XH. Soft Matter. 2014;10:672. doi: 10.1039/C3SM52272E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu ZL, Tantakitti F, Yu T, Palmer LC, Schatz GC, Stupp SI. Science. 2016;351:497. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka H. J Phys Condens Matter. 2000;12:R207. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gent AN. J Mater Sci. 1970;5:925. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stukalin EB, Cai LH, Kumar NA, Leibler L, Rubinstein M. Macromolecules. 2013;46:7525. doi: 10.1021/ma401111n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doig AJ, Williams DH. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:338. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferry JD. Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers. 3rd. Wiley; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]; Rubinstein M, Colby RH. Polymer Physics. New York: Oxford University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Black AL, Lenhardt JM, Craig SL. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:1655. [Google Scholar]; Yount WC, Loveless DM, Craig SL. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2005;44:2746. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lenhardt JM, Ong MT, Choe R, Evenhuis CR, Martinez TJ, Craig SL. Science. 2010;329:1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1193412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greensmith HW. J Appl Polym Sci. 1963;7:993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakulkaew K, Thomas AG, Busfield JJC. Polym Test. 2011;30:163. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ducrot E, Chen Y, Bulters M, Sijbesma RP, Creton C. Science. 2014;344:186. doi: 10.1126/science.1248494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neal JA, Mozhdehi D, Guan Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2015 doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cromwell OR, Chung J, Guan Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:6492. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Amamoto Y, Otsuka H, Takahara A, Matyjaszewski K. Adv Mater. 2012;24:3975. doi: 10.1002/adma.201201928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ling J, Rong MZ, Zhang MQ. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:18373. [Google Scholar]; Ying H, Zhang Y, Cheng J. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3218. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chortos A, Liu J, Bao ZN. Nat Mater. 2016;15:937. doi: 10.1038/nmat4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bao ZN, Chen XD. Adv Mater. 2016;28:4177. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Someya T, Bao ZN, Malliaras GG. Nature. 2016;540:379. doi: 10.1038/nature21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.