Abstract

Background: Different concentrations of the simple carbon substrates i.e. glucose, fructose, and sucrose were tested to enhance the performance of the mediator-less double chamber microbial fuel cell (MFC).

Objectives: The power generation potential of the different electron donors was studied using a mesophilic Fe (III) reducer and non-fermentative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa-isolated from municipal wastewater.

Materials and Methods: A double chamber MFC was operated with three different electron donors including glucose, sucrose, and fructose. Substrate utilization pattern was determined through chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal rate and voltage generation. In addition, electrochemical, physicochemical, and microscopic analysis of the anodic biofilm was conducted.

Results: P. aeruginosa was proven to effectively utilize hexose and pentose sugars through anode respiration. Higher power density was generated from glucose (136 ± 87 mWm2) lead by fructose (3.6 ± 1.6 mWm2) and sucrose (8.606 ± mWm2). Furthermore, a direct relation was demonstrated between current generation rate and COD removal efficiency. COD removal rates were, 88.5% ± 4.3%, 67.5% ± 2.6%, and 54.2% ± 1.9% with the three respective sugars in MFC. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) demonstrated that the bacterial attachment was considerably abundant in glucose fed MFC than in the fructose and sucrose operated MFC.

Conclusion: This study has revealed that electron donor type in the anodic compartment controls the growth of anodic biofilm or anode-respiring bacteria (ARB).

Keywords: Anode respiring bacteria, Biofilm, Double chamber MFC, Electron donors, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

1. Background

In the last few decades, a demand for the alternative energy sources has been felt worldwide due to depletion of the natural resources. The significance of energy-rich waste has led to the emergence of waste driven technologies (1). In this context, MFC technology is a promising approach with the ability to derive the electrical energy using catalytic (i.e. metabolic) ability of the bacteria from a variety of organic wastes (2). This proposes an opportunity for the simultaneous wastewater (organic waste liquor) treatment as well as electricity generation.

In MFC the strict/facultative anaerobic bacteria oxidize organic substrates as part of their energy metabolism liberating electrons and protons. Electrons are picked up from bacterial cell surface to the anode directly through pili and flagella or indirectly via electron shuttles. Subsequently, an electron is conducted towards cathode in order to directly convert chemical energy into electrical energy achieving wastewater treatment. Protons on the other side are transported to the cathode chamber through a proton conducting material like Nafion membrane (3) or salt bridge where it combines with the electron and oxygen to form water using different biological or chemical catalysts (4, 5).

Previously, both pure (6) and mixed culture biofilms (7) have been used for the production of electricity in MFC. Bacterial species such as Rhodoferax ferrireducens (8), Shewanella (9) and Geobactersul furreducens (10) are able to directly transfer electrons to the anode through c-type cytochromes or nanowires; appendages e.g. pili and flagella in this context (11). The identification of P. aeruginosa from Proteobacteria phylum; as an anode respiring bacteria (ARB) was an important physiological discovery as these bacteria are mesophilic, non-fermentative, and aerobic. In addition to direct electron transfer, Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been reported to use their own electron mediators (e.g. phenazine-1-carboxylic acid, pyocyanin etc.) that enable them to survive under anaerobic condition (12). Fermentative microorganisms lead to lower columbic efficiency as electric current due to the reduced recovery of electrons from the substrate. Fermentative bacteria assimilate electrons derived from the substrate into certain primary metabolic products that include organic acids, hydrogen, and alcohols rendering them electrochemically inactive. Mediator-less MFCs have a perspective for the generating electricity from anaerobic sediments and sewage. Numerous studies have been done to improve the architecture and the associated efficiency of the MFC by enriching bacteria from different habitats (13).

There are numerous aspects that affect the operational efficiency of MFC such as the type of substrates and loading rate, bacterial metabolism, catalysts, electrodes (surface area and the distance between them), mediators, proton exchange membrane (PEM) etc. (14). The process optimization and greater application in future require further investigation on these systems. The pure culture MFC is vital in determining the competence of a specific bacteria to harvest electric current (15, 16) . A variety of electron donors has been used as substrates in MFC ranging from the simply defined substrates to the complex organic mixtures. The defined substrates, generally in the form oflactate, glucose, starch, acetate, sucrose etc., contain an instant source of carbon (17). The power generated by MFCs may vary depending on the metabolic capability of the electrigenic bacteria, substrate availability and mass transfer ratio (8, 11, 18).

2. Objectives

The main purpose of this study was to enhance the performance of the mediator-less double chamber MFC to generate electrical energy from the simple carbon substratesi.e. glucose, fructose and sucrose with the varied concentrations. The main focus was to analyze the effect of different substrates’ concentration (1-5 g.L-1) as well as type; substrates such as glucose, sucrose, and fructose as an electron donor using non-fermentative bacteria, P. aeruginosa isolated from municipal wastewater. The charge-discharge cycling performances for the MFC using carbon sugars were also tested. The model substrate and optimum concentration were determined by measuring voltage output and COD removal, increase in the MFC energy efficiency correlates with the optimal electrochemical activity of the bacteria. Additionally, we carried out the detailed electrochemical, physicochemical, and microscopic analysis of the anodic biofilm to understand MFC performance efficiency.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

The analytical grade culture media and chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemicals Corporations, Oxoid company, UK, DIFCO Laboratories (Michigan, USA), Gas Hub Pte Ltd, Du Pont Company, Fluka chemicals corporations (UK), and Merck (United States). The digital multimeter (model: UT33B; UNI-T) was obtained from Globalmedia Pro (New Zealand).

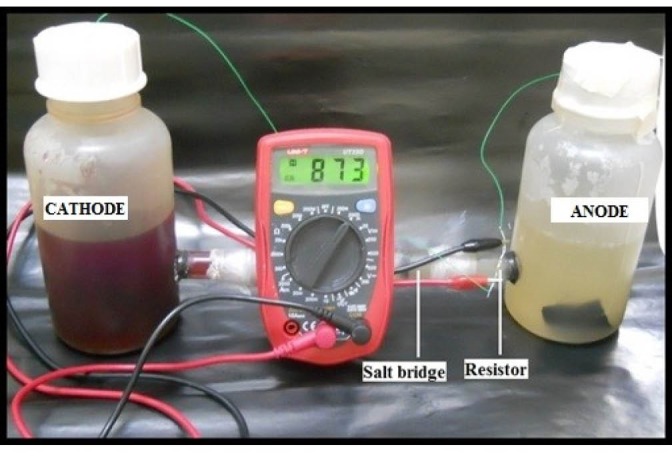

3.2. Double Chamber MFC Construction

Double chamber MFC (Fig. 1) was constructed with two 500 mL plastic bottles (working volume 300 mL) joined with tubes attached to each bottle and membrane chamber. The membrane chamber that holds 25 cm2 of Nafion 115 (Gas Hub Pte Ltd, Du Pont Company 30 cm x 30 cm) was constructed using Plexi glass slab. A circle (26 cm2) was drilled in the middle of plexi slab to hold tubes housing membrane at the mouth; four holes were drilled along the outer dimension of each slab to hold 0.8 cm x 6.3 cm stainless steel screws. The membrane was placed between the mouths of the two tubes with epoxy and sealed together with screw and parafilm was wrapped around the junction of the tubes. Holes (26 cm2) were drilled through plastic bottles and membrane chamber was affixed between both bottles and the junction was sealed with epoxy glue. The anode and cathode were 3 × 5 cm2 carbon cloths (EC-CC1-060, no wetproofing) the electrodes were autoclaved before usage. 10% platinum catalyst layer was coated on the cathode. The copper wire (0.7 millimeters) was connected with the electrode with conductive sealant and inserted into each chamber through the lid.

Figure 1.

The experimental setup for a double chamber MFC.

3.3. Bacterial Isolation

The pure culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated from the domestic wastewater sample collected from the treatment plant; sector I-9 Islamabad, Pk. The Pseudomon ascetrimide media with a composition per liter of the pancreatic digest of gelatin 20 g.L-1, magnesium chloride 1.4 g.L-1, dipotassium sulfate 10 g.L-1, cetrimide 0.3 g.L-1, agar 13.6 g.L-1, and distilled water with a pH adjusted to 7 was used to cultivate P. aeruginosa. During the incubation period, environmental conditions were kept anaerobic using catalysts (Oxoid, UK) and anaerobic jar. Gram staining and biochemical analysis were carried out following the standard procedure.

3.4. Biofilm Formation

For formation of P. aeruginosa biofilm on the anode, 100 mL nutrient broth was taken in an Erlenmeyer flask, cotton plugged, and autoclaved (121 °C at 15 psi for 15 min). One full loop colony of P. aeruginosa was taken and inoculated in the media flask and at the same time, carbon cloth (anode) was also dipped in the culture medium for biofilm development at 37 °C. P. aeruginosa was inoculated in the nutrient broth and carbon cloth was placed in it for the biofilm formation. The media was refreshed after 3 days and 10% inoculum from the previous trail was added along with anodic biofilm in the new medium. The biofilm trial was run for the total of 21 days.

3.5. MFC Operation with Pure Culture Biofilm

MFC was operated with P. aeruginosa biofilm (21 days) in the batch mode. Anode chamber was filled with 280 mL of the growth medium containing glucose, sucrose, or fructose (1-5 g.L-1), 125 mL of 100 mM phosphate buffer solution (Na2HPO4 9.125 g.L-1, NaH2PO4·H2O 4.9 g.L-1, NH4Cl 0.62 g.L-1, KCl 0.26 g.L-1adjusted at pH 7) and 12.5 mL trace minerals solution (3 g MgSO4, 0.5 g MnSO4-H2O, 1.0 g NaCl, 0.1 g FeSO4-7H2O, 0.1 g CoCl2.6H2O, 0.1 g CaCl2.2H2O, 0.13 g ZnCl2, 0.01 g CuSO4-5H2O, 0.01 g AlK(SO)4-12H2O, 0.01 g H3BO3, 0.025 g Na2MoO4, 0.024 g NiCl2.6H2O, 0.025 g Na2WO4.2H2O) and vitamin solution (Thiamin, Riboflavin, nicotinic acid, 2 pyridoxine HCl, biotin, folic acid, riboflavin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, Vitamin B-12, Choline, Inositol). The constituents of the growth medium were aseptically filtrated and added by syringe to the anode. The anodic chamber of MFCs was purged with nitrogen gas (15 mL.min-1) to create anaerobic conditions. In the cathode chamber, 300 mL of 0.6 mM KMnO4 was used as catholyte. Each experiment was conducted in duplicate and observations were subjected to statistical analysis.

3.6. Measurement and Analysis

3.6.1. Electrochemical Analysis

MFC was initially operated at the open-circuit cell voltage V0. Afterward, the circuit was closed by applying 100 Ohms (Ω) resistor to achieve stable voltage. The voltage between electrodes was measured with a precision multimeter (UT33B; UNI-T) after every hour. The current (A) was calculated according to Ohm’s law (I = V/R) where V = voltage and R= resistance (Ω). The power (W) was calculated from a voltage and current using P = IV and the power density (Wm-2) as P = Current (A) × Volts (V)/Surface area of the anode (m2) and Current density (Am-2) as current (A)/Surface area of anode (m2). Polarization curve was obtained by varying external resistances (copper wire resistors) from 20 Ω to 80,000 Ω. Data from each resistor was recorded after a stable voltage was attained.

3.6.2. Physicochemical Analysis

The chemical oxygen demand (COD) and biological oxygen demand (BOD) were determined in accordance with the Standard Methods for the Examination of Wastewater treatment. The initial COD of glucose medium (C6H1212O6, MW = 180.17), sucrose medium (C12H22O11, MW = 342.30), and fructose medium (C6H12O6, MW = 180.16) were investigated by theoretical chemical oxygen demand on the basis of its stoichiometric reaction with oxygen. The final COD was measured with COD kits (HACH COD system, HACH Co., Loveland, CO) ranged from 1 to1500 mg.L-1. COD removal was calculated as; [(CODin - CODout)/CODin] ×100%. Where COD in is the influent COD and CODout the effluent COD. The initial and final BOD5 of the anodic solution was determined using 5210 B Standard Method (APHA, 2005).

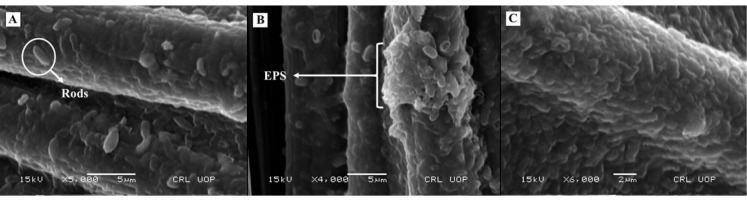

3.6.3. Microscopic Analysis

SEM analysis of the biofilm on Carbon clothes/anodes was investigated at high resolution to confirm the bacterial infestation. The anode material was removed at the end of the experiment, rinsed with the sterile medium (distilled water), and then immersed in the 5% formaldehyde overnight to fix the samples. Chips of 1 cm×1 cm were cut for SEM analysis. Before observation the anodic materials were collected and immersed in the 5% formaldehyde overnight for fixing samples, followed by washing with detergent, and drying using the drier. Silver paste conduction (SPI-CHEM) was done on the dried sample to ensure the conduction of the electron beam. Finally, the surface morphology of the biofilm was observed on the screen under 3000 and 5000 magnification power in 30KV SEM.

4. Result

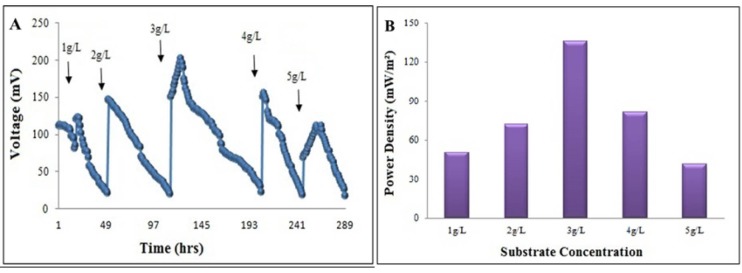

4.1. Energy Generation with Glucose

At the end of biofilm formation (21 days) the anodic medium was replaced with a new medium containing different concentrations of glucose as an electron donor and potassium permanganate (K2MnO4) as an electron acceptor. A gradual increase in the voltage was observed without any lag phase when 1 g.L-1glucose was fed into the reactor and reached up to a maximum value of 122.1 mV in 24 h. The voltage declined to 20 mV in 49 h. With each reloading of glucose, the maximum voltage was achieved approximately in 12 h (Fig. 2A). The increase in the voltage was found to be directly proportional to the glucose concentration from 1-3 g.L-1. A maximum voltage (i.e. 202 mV) was generated with 3 g.L-1glucose and sustained for a period of 2-3 h. Beyond 3 g.L-1glucose, a gradual fall in the cell voltage was observed. At 3 g.L-1glucose and an external resistance of 100 Ω the power and current densities were 136 mWm-2 and 673mAm-2, respectively (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

The effect of different concentrations of glucose on voltage (A) and power density (B) in the double chamber MFC.

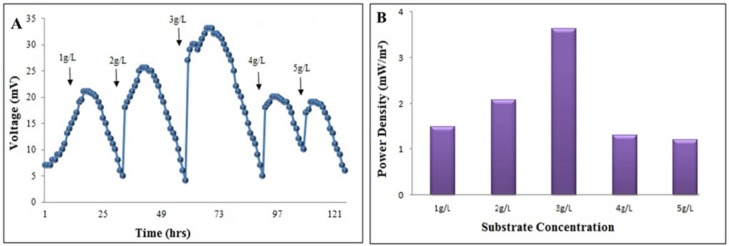

4.2. Energy Generation with Fructose

The grown P. aeruginosa biofilm (21 days) was fed with medium containing different concentrations of fructose. 1 g.L-1fructose in anode and K2MnO4 in cathode generated a voltage of 7 mV in the first 4 h. which then reached a maximum value of 21 mV in 15 h. Afterward, it started declining and reached to 5 mV at 30th h. The same pattern of voltage generation was observed when MFC was run with different concentrations of fructose (1-5 g.L-1). However, a sharp increase in voltage was always observed after each reloading of the substrate (Fig. 3A ). The maximum voltage of 33 mV was generated with 3 g.L-1of fructose and a further increase in the fructose concentration resulted in a significant fall in the cell voltage (Fig. 3B). The current and power densities at an external resistance of 100 Ω were 100 mAm-2 and 3.6mWm-2, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of different concentrations of fructose on (A) voltage; (B) power generation of the double chamber MFC.

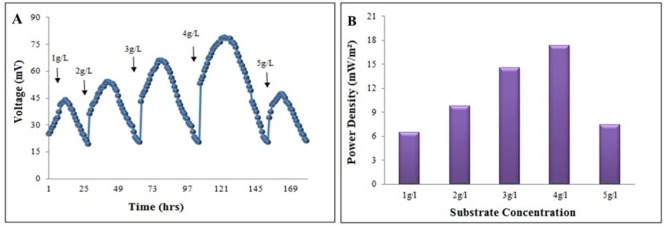

4.3. Energy Generation with Sucrose

When MFC with mature P. aeruginosa biofilm was loaded with 1 g.L-1of sucrose (disaccharide) the voltage was gradually increased to a maximum value of 45 mV in 12 h. (Fig. 4A) and then declined to 20 mV in 24 h. The voltage was reached to a plateau stage in about 4 h, then started to decrease. The maximum power density generated with 4 g.L-1sucrose was 20.80 mWm-2 (Fig. 4B) at the current density of 0.26 mAm-2 (external resistance 100 Ω). At a concentration of 4 g.L-1, the circuit resistance was varied from 20 Ω - 80,000 Ω in order to determine the maximum power density as a function of external load. At 4 g.L-1 of sucrose, a stabilized voltage of 79 mV was generated with a COD removal efficiency of 54.2 % within 24 h.

Figure 4.

The electrochemical response of the different applied concentrations of the sucrose. (A) The generated voltage and (B) the power density.

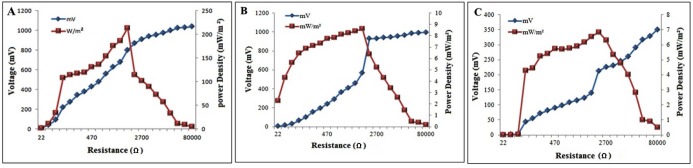

4.4. Polarization Study

After attaining the stable performance, the effect of external resistance on MFC operation was examined by varying the external resistance i.e. from 20 Ω to 80,000 Ω.The data was recorded from each resistor after a stable voltage was established. The power density and polarization curves were achieved from polarization test. Carrying out the polarization study by using 3 g.L-1glucose has revealed that the maximum power density of 213 mWm-2 could be obtained at the external resistance of 1000 Ω when the voltage is set on 770 mV (Fig. 5A). However, with a concentration of 3 g.L-1of fructose the maximum power density of 6.84 mWm-2 was reached at the external resistance of 2.2 KΩ when the voltage was 212.5 mV (Fig. 5B). After normalization of power on the surface area of the anode the highest power density of 8.606 mWm-2 and the current density of 0.26 mAm-2 was recorded with 4 g.L-1of sucrose at an external resistance of 1000 Ω (Fig. 5C) when the voltage was 568 mV.

Figure 5.

Voltage and power generation as a function of the circuit load (resistance) in the double chamber MFC operated with A) glucose B) fructose, and C) sucrose.

4.5. COD Removal

The COD removal was observed during MFC operation with 100 Ω resistance. The extent of COD removal was different with various substrate type (Table 1); the maximum of which was 88.5 % with 3 g.L-1of glucose after 12 h and 91% was achieved with 5 g.L-1. However, the COD removal with fructose was lesser than glucose with a maximum COD removal of 67.5% in 61 h with 3 g.L-1of fructose. At 4 g.L-1 of sucrose, stabilized voltage of 79 mV was generated with a COD removal efficiency of 54.2 % in 24 h.

Table 1. The COD removal efficiency using glucose, fructose, and sucrose, respectively.

| Substrate (g.L -1 ) | COD Removal Efficiency (%) | ||

| Glucose | Fructose | Sucrose | |

| 1 | 81.9 | 25.9 | 29.8 |

| 2 | 86.7 | 34.8 | 56.5 |

| 3 | 88.5 | 67.5 | 55.3 |

| 4 | 88.7 | 22.3 | 54.2 |

| 5 | 91 | 17.5 | 44.7 |

4.6. SEM Analysis

The bacterial colonization on the anodic surface from glucose, fructose, and sucrose-fed MFCs was analyzed via SEM analysis. A thick smooth coverage of biomass was evident on carbon cloth fiber in all three SEM images. The bacterial density on anodic biofilm is a major factor that governs power density in MFC. The microbial attachment was abundant in the glucose-fed MFC than fructose and sucrose operated MFC (Fig. 6). SEM imaging revealed the morphology of individual cells as most of the cells were rods shaped. The biofilm components such as bacterial cells and exopolysaccharides (EPS) matrix are highlighted in SEM analysis (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging of the pure culture anodic biofilm of the P. aeruginosa developed in A) glucose fed MFC, B) fructose fed MFC, and C) sucrose fed MFC, respectively.

5. Discussion

MFC is a sustainable technology that has the potential for treating wastewater with simultaneous generation of electricity. In the recent past, several modifications have been made in designing in order to engineer a cost-effective MFC model that could generate high power output along with its practical implication in a large scale (19). Typically, the two main types of designs are commonly used (i.e. the double chamber and a single chamber, respectively). Double chamber MFC with the separate anode and cathode chambers are employed for studying and optimizing different operational parameters in order to generate the higher electric power outputs (14, 20, 21). On this basis, the current study has been conducted to evaluate the comparative operational efficiency of the different electron donors in a double chamber MFC.

Various simple to complex substrates has been used as an electron donor (17, 22) for power generation. These include acetate and glucose, galactose, ribose, sucrose, xylose, molasses, cellulose, and whey with varying efficiencies (23). Previously, current density has been reported for the single chamber MFC applying glucose (0.07 mAcm-2), fructose (0.5 mAcm-2), and acetate (0.6 mAcm-2) (24). In the former studies, the double chamber MFC operated with the glucose (5 g.L-1) has shown to generate power of 50 mWm-2 (25) and 104 mWm-2 (26). Moreover, MFC utilizing fructose and sucrose as carbon source showed the maximum current density of 0.003 mAcm-2and 0.0193 mAcm-2, respectively (27) which are significantly lower in comparison to our findings. The pure cultures of various electricity generating bacteria can only utilize certain substrates, e.g., Geobacter species are limited to organic acids, ethanol, and aromatic compounds. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was selected in this study for its non-fermentative ability. Under anaerobic conditions, the fermentative bacteria metabolize carbon substrates into certain primary products such as organic acids, and alcohols. This minimizes current generation through MFC due to a lowered columbic efficiency and limited recovery of electrons from the substrate.

In this study when glucose was used as an electron donor in double chamber MFC, a power density of 136 mWm-2 was produced with 3 g.L-1concentration of glucose (Fig. 2A). The voltage was gradually increased with an increased glucose concentration (1-3 g.L-1), but beyond 3 g.L-1energy generation was decreased. Similarly, when fructose and sucrose were used as the substrate, the power was gradually increased and appearance of the plateau in the voltage curve occurred at high substrate concentration (Fig. 3A, 4B). This can be attributed to the substrate inhibition effect, as at high concentration most of the substrate remained unconsumed (28, 29). Initially, the power generation was increased with an increased concentration of electron donor, but, a further increase in concentration did not produce any significant change in the power density. As substrate concentration was increased, constant voltage generation was attained in a shorter time with a lower power production. This may be due to inhibitory effects resulted from the formation of metabolic byproducts such as organic acids, formic acid, lactic acid, and acetic acid at high concentration (30). This exhibits a deteriorating effect on the bacterial metabolism, thus inhibiting the growth. Moreover, the high substrate concentration restricts bacteria to utilize carbon contents of the electron donors. This was due to inhibition of proteinaceous enzymes that reduce the microbial ability to breakdown proteinaceous resources(31).

6. Conclusion

This study has illustrated the effect of electron donor concentration and type on the power output of a double chamber MFC. Various simple substrates such as glucose, fructose, and sucrose were used as electron donors with P. aeruginosa as the biocatalyst for generation of electric energy in the double chamber MFC. Several concentrations of carbon substrates at the range of 1-5 g.L-1were studied. The experimental results have revealed that optimum concentration for the maximum performance of MFC was 3 g.L-1for glucose and fructose, whereas, it was 4 g.L-1for sucrose. Comparing different carbon substrates as the electron donors, glucose has resulted in the maximum power density (i.e., 136 mWm-2 and the current density of 673 mAm-2 at a concentration of 3 g.L-1. Moreover, this study has demonstrated that COD removal efficiency has a direct relation with the current generation rate. Furthermore, results have indicated the impact of substrate inhibition effect on the MFC performance.

References

- 1.Minteer SD, Atanassov P, Luckarift HR, Johnson GR. New materials for biological fuel cells. Mater Today. 2012;15(4):166–173. doi: 10.1016/s1369-7021(12)70070-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schröder U. Editorial: Microbial Fuel Cells and Microbial Electrochemistry: Into the Next Century! ChemSusChem. 2012;5(6):959. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201200319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali N, Yousaf S, Anam M, Bangash Z, Maleeha S. Evaluating the efficiency of mixed culture biofilm for the treatment of black liquor and molasses in mediator less microbial fuel cell. Environ Technol. 2016;37(22):2815–2822. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2016.1166267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan BE, Regan JM. Microbial fuel cells-challenges and applications. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40(17):5172–80. doi: 10.1021/es0627592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lies DP, Hernandez ME, Kappler A, Mielke RE, Gralnick JA, Newman DK. Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 uses overlapping pathways for iron reduction at a distance and by direct contact under conditions relevant for biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(8):4414–4426. doi: 10.1128/aem.71.8.4414-4426.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim HJ, Park HS, Hyun MS, Chang IS, Kim M, Kim BH. A mediator-less microbial fuel cell using a metal reducing bacterium, Shewanella putrefaciens. Enzyme Microb Techno. 2002;30(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/s0141-0229(01)00478-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang G, Zhao Q, Jiao Y, Wang K, Lee D-J, Ren N. Efficient electricity generation from sewage sludge usingbiocathode microbial fuel cell. Water Res. 2012;46(1):43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z, Du Z, Lian J, Zhu X, Li S, Li H. Improving energy accumulation of microbial fuel cells by metabolism regulation using Rhodoferax ferrireducens as biocatalyst. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2007;44(4):393–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang T, Zeng Y, Chen S, Ai X, Yang H. Improved performances of E coli-catalyzed microbial fuel cells with composite graphite/PTFE anodes. Electrochem Commun. 2007;9(3):349–53. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2006.09.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reguera G, Nevin KP, Nicoll JS, Covalla SF, Woodard TL, Lovley DR. Biofilm and nanowire production leads to increased current in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells Appl. Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(11):7345–7348. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01444-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boon N, Aelterman P, Clauwaert P, De Schamphelaire L, Vanhaecke L, De Maeyer K. et al. Metabolites produced by Pseudomonas sp enable a Gram-positive bacterium to achieve extracellular electron transfer. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;77(5):1119–1129. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousaf S, Anam M, Ali N. Evaluating the production and bio-stimulating effect of 5-methyl 1, hydroxy phenazine on microbial fuel cell performance. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2017;14(7):1439–1450. doi: 10.1007/s13762-016-1241-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hou H, Li L, Ceylan CÜ, Haynes A, Cope J, Wilkinson HH. et al. A microfluidic microbial fuel cell array that supports long-term multiplexed analyses of electricigens. Lab chip. 2012;12(20):4151–4159. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40405b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhi W, Ge Z, He Z, Zhang H. Methods for understanding microbial community structures and functions in microbial fuel cells: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2014;171:461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jafary T, Ghoreyshi AA, Najafpour GD, Fatemi S, Rahimnejad M. Investigation on performance of microbial fuel cells based on carbon sources and kinetic models. Int J Energy Res. 2013;37(12):1539–1549. doi: 10.1002/er.2994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma SK, Bulchandani B. Energy Generation by Microorganisms using Carbohydrate Substrates in a Microbial Fuel Cell. Inter J Business Engin Res. 2014;8:27–31. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan SH, Kim YS, Oh S-E. Power generation from cellulose using mixed and pure cultures of cellulose-degrading bacteria in a microbial fuel cell. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2012;51(5):269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malvankar NS, Tuominen MT, Lovley DR. Lack of cytochrome involvement in long-range electron transport through conductive biofilms and nanowires of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5(9):8651–8659. doi: 10.1039/C2EE22330A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ge Z, Li J, Xiao L, Tong Y, He Z. Recovery of electrical energy in microbial fuel cells: brief review. Environ Sci Technol Lett. 2013;1(2):137–141. doi: 10.1021/ez4000324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mardanpour MM, Esfahany MN, Behzad T, Sedaqatvand R. Single chamber microbial fuel cell with spiral anode for dairy wastewater treatment. Biosensors Bioelectron. 2012;38(1):264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agler MT, Wrenn BA, Zinder SH, Angenent LT. Waste to bioproduct conversion with undefined mixed cultures: the carboxylate platform. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29(2):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nimje VR, Chen C-Y, Chen H-R, Chen C-C, Huang YM, Tseng M-J. et al. Comparative bioelectricity production from various wastewaters in microbial fuel cells using mixed cultures and a pure strain of Shewanella oneidensis. Bioresour Technol. 2012;104:315–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.09.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solanki K, Subramanian S, Basu S. Microbial fuel cells for azo dye treatment with electricity generation: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2013;131:564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pant D, Van Bogaert G, Diels L, Vanbroekhoven K. A review of the substrates used in microbial fuel cells (MFCs) for sustainable energy production. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101(6):1533–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ghoreyshi A, Jafary T, Najafpour G, Haghparast F, editors. Effect of type and concentration of substrate on power generation in a dual chambered microbial fuel cell. World Renewable Energy Congress-Sweden; 8-13 May; 2011; Linköping; Sweden; Linköping University Electronic Press.

- 26.Yoganathan K, Ganesh P. Electrogenicity assessment of Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus megaterium using Microbial Fuel Cell technology. Int J Appl Res. 2015;1(13):435–438. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali AE-H, Gomaa OM, Fathey R, El Kareem HA, Zaid MA. Optimization of double chamber microbial fuel cell for domestic wastewater treatment and electricity production. J Fuel Technol Chem. 2015;43(9):1092–1099. doi: 10.1007/s13213-015-1152-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng S, Logan BE. Increasing power generation for scaling up single-chamber air cathode microbial fuel cells. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(6):4468–4473. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.12.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei J, Liang P, Huang X. Recent progress in electrodes for microbial fuel cells. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102(20):9335–9344. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M, Yan Z, Huang B, Zhao J, Liu R. Electricity generation by microbial fuel cells fuelled with Enteromorpha prolifera hydrolysis. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2013;8:2104–2111. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pandey P, Shinde VN, Deopurkar RL, Kale SP, Patil SA, Pant D. Recent advances in the use of different substrates in microbial fuel cells toward wastewater treatment and simultaneous energy recovery. Appl Energy. 2016;168:706–723. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.01.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]